“The art of tropical Africa from the collection of M.L. and L.M. Zvyagin

Mysteries of Nok Culture

In 1949, the opening of the exhibition "Traditional Art of the British Colonies" was announced in London. The art of Africa at that time was already well known in Europe and enjoyed well-deserved recognition. It is widely represented in all the major museums of the world, many books, albums, articles are devoted to it, the study of it is included in the curricula along with the study of classical and contemporary art. Therefore, although such exhibitions usually attract big number visitors, they nevertheless do not promise anything unexpected.

However, this time it was not so...

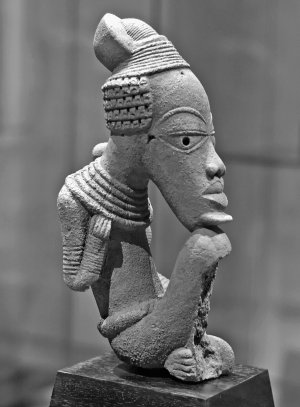

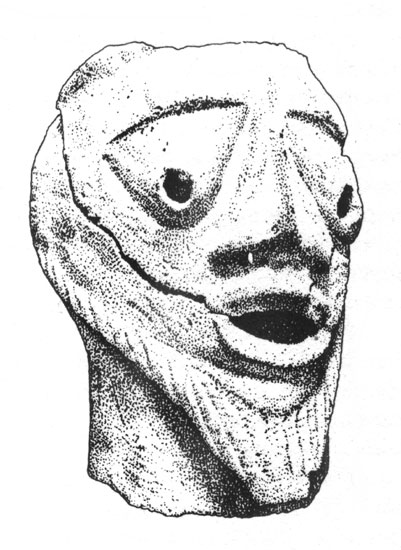

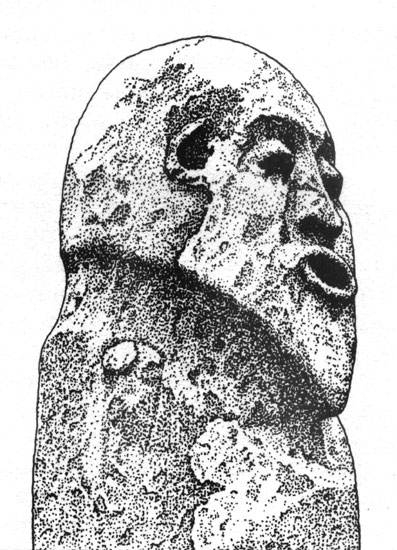

Passing through the exhibition halls, visitors stopped in amazement at a stand with a strange terracotta sculpture, unlike any of the many exhibits of this exhibition. An unusually expressive head made of brownish baked clay seemed to hypnotize with wide-open eyes with black, deeply drilled pupils. A huge overhanging domed forehead, high brow ridges, a small finely modeled straight nose, a mustache, a beard turning into a narrow strip of whiskers - every detail of this head and the whole sculpture as a whole made a strange impression against the background of ordinary traditional masks and figurines.

Terracotta sculpture Nok

The mysterious terracotta sculpture aroused great admiration among amateurs and artists and seriously puzzled specialists. The annotation stated that the sculpture comes from Northern Nigeria. However, nothing similar to the style of this sculpture has yet been found either in Nigeria or anywhere else. Her age was also unusual - the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. e. In other words, the strange terracotta head is more than a millennium older than the oldest Ife bronze and terracotta sculptures!

The sculpture, named after the place where the first finds were made (the valley and village of Nok in Northern Nigeria), was discovered under rather unusual circumstances.

Tin mines have existed in the southern regions of Northern Nigeria for more than half a century, the development of which is carried out by an open method. In 1943, in one of the mines, fragments of ceramics were extracted from under an eight-meter layer of rock, which attracted the attention of specialists. Studies conducted here by the English archaeologist B. Fagg showed that during their development, many interesting objects were thrown to the surface along with the earth, including unique works of art: terracotta heads, figurines, various ornaments, etc. did all these man-made things get into ore deposits? Here is how this process is explained: “In the second half of the 1st millennium BC. e. middle Africa from Nigeria to Kenya experienced a "wet phase" (which geologists call "nakuru", after the city of Nakuru in Kenya). At this time, in the elevated part of Central Nigeria, there was an extensive river system, through which rainwater flowed into the Benue valley, and then through the lower Niger to the bay of Benin. In those days, the rivers played a much more significant role in the life of the peoples of central Nigeria than they do today, and the landscape of the country was very different from the modern one. Huge masses of soils, apparently, were rapidly eroded, and the products of this decay, carried away by water, were deposited in the alluvial layers; heavier mineral rocks were deposited in rivers faster than lighter ones. This heavy rainfall, rich in cassiterium ("tin earth"), created the soil for the modern tin mining industry in Nigeria.

But the places of human settlement were also subjected to erosion. Residents of many coastal villages were forced to hastily leave their homes and sacrifice their homes to the water element. As a result, the alluvial layers are rich not only in mineral deposits, but also in various products such as polished stone axes, ritual objects, ornaments, which fell into the river after the sacred houses were abandoned. Almost without exception, all of them were broken into pieces, but, fortunately, the heads of the terracotta figures, like human skulls, are better preserved than the rest of the figures, due to their spherical shape, especially in cases where they fell into natural shelters at the bottom of the river. ".

So, thanks to pure chance, priceless works of ancient African sculpture have been preserved in the deposits of tin ore. The high technical skill and finished style of art objects found in the mines near the village of Nok testified that archaeologists were lucky to discover an unknown culture that existed for a long time, and it was natural to assume that it could not be territorially limited to one or two points.

Surveys carried out at neighboring tin and gold mines have given new material, moreover, artistic products found in various and often far from each other points showed a pronounced stylistic similarity with previously found sculpture.

The style of the heads and fragments of the terracotta statues currently in the museum of the city of Jos (Nigeria) is irrefutable evidence of their belonging to the same culture: “First of all, they amaze with an amazing variety of forms, which is combined with a deep unity of style, which makes it possible to unmistakably attribute them to one “art school”, despite the fact that one of the fragments approaches what we would call naturalistic style, while the other is so far removed from it that it can only hardly be classified as figurative art ... and the general formal features are very simple ; first of all, this is a special interpretation of the eyes, which usually approaches a triangular or semicircular shape, as well as nasal and ear openings (sometimes also the mouth).

If we talk about the plastic forms of this sculpture, and not about technical methods, such as, for example, drilling (which determines the shape of the pupil, ear, etc.), then it should be noted that it is precisely this variety that catches the eye, and not features of stylistic similarity, which appear here as if contrary to the intentions of the artist, who strove to create completely different, original, sharply expressive images. For example, the shape of the head, which seems to be the least transformable, changes in an unexpected way. It can take a variety of forms: either a cone with its tip up or down, or a ball or cylinder. The ears, sometimes marked only by small indentations, in other cases take on a bizarre shape and reach enormous sizes (even a special substyle of “long-eared heads” is distinguished).

Only one external feature unites almost all Nok heads - this is the way the eyes are depicted. It is noted that the eyes of most terracotta heads have a deeply drilled pupil, a straight upper eyelid and a lower one in the form of a semicircle or an isosceles triangle. It should be added that the same unity is preserved in the interpretation of arched eyebrows superimposed on top in the form of a braided lace. The uniformity of these details is all the more surprising since it is the eyes that are the element of traditional African plastic arts that is interpreted in the most diverse ways.

A similar shape of the eye can be found in Africa in the art of only one of the modern peoples - in the art of the Yoruba.

Even greater stylistic parallels with Nok art are found in the ancient, but historically more late art the same country - in the art of Ife. In addition to similar subjects, such as, for example, the image of people suffering from elephantiasis, and various small objects and decorations, there are whole statues in Ife sculpture that have found their counterparts among Nok sculptures.

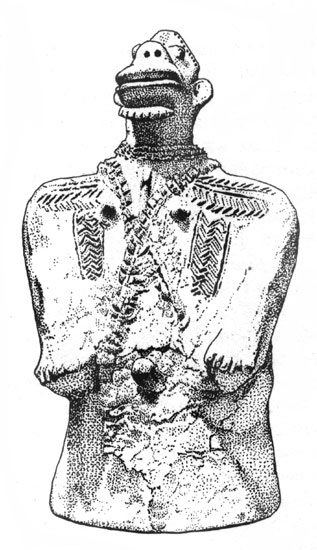

One of them, a headless terracotta figure found in Jemaa, is strikingly similar to a bronze statue made in the Ife tradition (found in Benin). The sizes and proportions of these statues are exactly the same. Looking more closely, you can see that not only the proportions, but also the nature of the modeling, for example, the feet and other details, is repeated in all details. On the torsos of both figures, of which one is male and the other is female, there are identical decorations in the form of a belt and a necklace. If it were not for the huge time span of 1000 years that separates the two cultures, one could say that they correlate with each other, like the sculpture of Greece during the archaic period and the sculpture of the Phidias era.

The proportions of the statue and fragments of the Nok figures also testify to their stylistic closeness to modern African sculpture. One of the distinguishing features of traditional African wooden sculpture is that the heads of the statues are greatly enlarged in relation to the torso and usually occupy a third or fourth part of the entire figure in height. Few of the surviving complete Nok figurines have exactly the same proportions of the main parts. There are other analogies: for example, the so-called head of Janus, found in Nok, reproduces one of the typical images of traditional African sculpture, which is found here among many peoples from Guinea to the Congo. Although there are few such direct analogies, they nevertheless provide sufficient grounds for comparing the newly discovered sculpture with local artistic traditions.

To whom does this culture owe its appearance and what is its place in the art of the peoples of Africa?

The author of the discovery, the English archaeologist Bernard Fagg and his brother art critic William Fagg, believed that the creators of the Nok culture were the ancestors of the tribes inhabiting the central regions of Nigeria.

The presence of metal objects in the deposits of the Nok culture, as well as the finds of some organic remains, including a tree trunk peeled from the bark, which made it possible to date by radiocarbon dating, made it possible to establish the heyday of this culture, which falls approximately on the third century BC. e. (the lower layer, in which the objects were found, is dated 900 BC; the layer that covered them is the 2nd century).

Studies that have not yet been completed show an already vast area of distribution of this culture, the total area of \u200b\u200bwhich exceeds 500 km from west to east and 360 km from north to south.

The wide dissemination of the Nok culture, its advanced age (more than two thousand years), and most importantly, its complete, mature style changed the idea of history. visual arts peoples of Africa, forced to reconsider the attitude not only to the ancient, but also to the later wooden sculpture of the last one or two centuries.

Until recently, there were many very different points of view on this sculpture: some consider it a product of evolution, which was allegedly based on samples of naturalistic art brought to Africa from Europe; according to others, the specific styles of African plastic arts are an expression of a special religious and philosophical concept inherent exclusively in African peoples - the embodiment of some kind of "life force"; some consider African sculpture the only true art, speaking language plastic symbols in contrast to the "literary" language of European sculpture, others - that African masks and figurines are not works of art at all, since they always have a certain "utilitarian" purpose, etc.

The conditional, symbolic nature of African sculpture, which gives it a mysterious, mystical coloring in our eyes, can only be correctly understood in the light of successive stages in the evolution of artistic forms, in the light of those gradual changes that led to the emergence of specific styles of late traditional plastics. Most of the dark and paradoxical statements that are replete with the literature on African art are partly due to the lack of material, partly ignoring those already known historical factors, under the influence of which the genres and styles of African sculpture of the last two centuries were formed and shaped.

As a result, the language of symbols and plastic ideograms used by African sculpture is sometimes perceived as a product of some special, self-contained culture.

However, these white spots are steadily shrinking. Until recently, only the so-called tribal, traditional art of the last one or two centuries was relatively well known. In addition to the famous centers of art - Ife and Benin - new centers have now been added, discovered in various parts of Western Tropical Africa, in particular the Sao and Nok cultures, which shed light on the early periods of the development of art on the African continent.

Mysteries of Ife

Probably, many people remember the fantastic story of the Atlanteans' migration from Earth to Mars in Aelita by Alexei Tolstoy. In an abandoned Martian house, the inventor Moose finds traces of Atlanteans - "glued vases, strangely reminiscent of Etruscan amphorae in shape and pattern," and a golden mask. “It was an image of a wide-cheeked human face with eyes calmly closed. The moon-shaped mouth smiled. The nose is sharp, with a beak. There is a swelling on the forehead and between the eyebrows in the form of an enlarged dragonfly eye ... The elk burned half the box of matches, examining the amazing mask with excitement. Shortly before leaving Earth, he saw photographs of similar masks recently discovered among the ruins of giant cities along the banks of the Niger in that part of Africa where traces of the culture of a disappeared mysterious race are now assumed.

In this passage, only the flight to Mars is a figment of the writer's imagination. African masks, their connection with Atlantis and the Etruscans are just an artistic interpretation of the scientific hypothesis of the prominent German archaeologist and ethnographer Leo Frobenius about the origin of one of the highest and most peculiar ancient civilizations of West Africa - the Ife culture, discovered in Yoruba - the country of the Yoruba people (Southwestern Nigeria ).

In the first quarter of the XIX century. English Hugh Clapperton and the Lander brothers managed to get to the interior of Nigeria, the country of the numerous Yoruba people. at the price own lives they explored previously inaccessible areas of the African continent and found there the ruins of a once powerful state, which was so named after its capital, located in the extreme northeast of the country. Judging by the legends, the rulers of the Oyo once obeyed a vast territory that included almost all of Nigeria, as well as modern Dahomey and Togo. By the name of one of the peoples inhabiting it, the Oyo was also called the Yoruba.

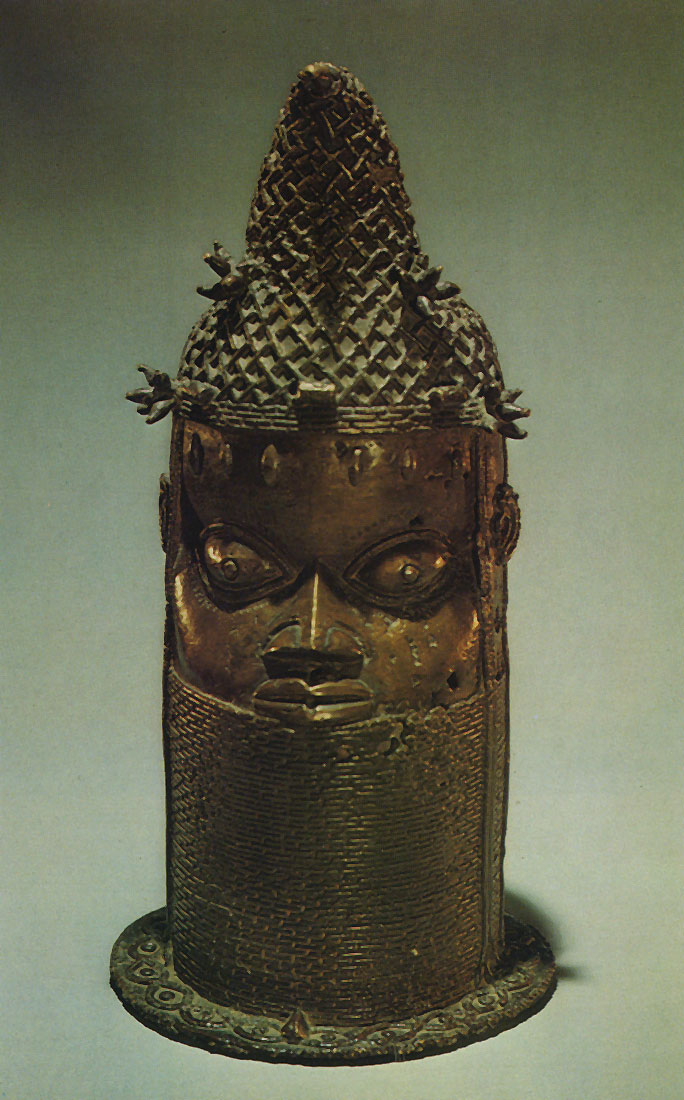

Head of the sea god Olokun from Ife

Yoruba legends told that once upon a time there was water in the place of the earth. Deciding to create the world, the god Olorun threw down a chain from the sky, along which the mythical ancestor of the Yoruba people, Oduduwa, descended to earth. He founded the city of Ife and began to rule in it. He was succeeded by a son - the great warrior Oranyan, who had countless offspring. So the city of Ife became the birthplace of mankind.

Within the Yoruba country, trade and crafts flourished. Oyo handicrafts, especially fabrics, were famous far beyond its borders. However, all this is in the distant past.

European travelers found the state already in a state of deep decline. They passed through huge fortified cities with a population of forty, sixty, one hundred thousand people and made sure that people had almost forgotten their former skills and achievements. The adobe fortress walls were destroyed, the fortress ditches were overgrown with grass and shrubs, and detachments of slave hunters scoured the caravan paths.

In 1825, almost all members of Clapperton's expedition, including himself, died from tropical diseases during a campaign to the Niger River. Only the youngest of the travelers, Richard Lender, who was 21 years old, managed to return to his homeland. In 1829, his two-volume work “Materials of the last African expedition of Clapperton” was published, and a little later the three-volume essay “Journey through Africa to explore the Niger to its mouth”. These works aroused in Europe even greater interest in the study of the Black Continent.

In 1910, the German scientist Leo Frobenius set out on a new journey through Nigeria. Long before his arrival in the country, he heard legends about the royal city of Ife from West African slaves taken to a foreign land.

In Nigeria, Frobenius was incredibly lucky. Literally from the first steps, he managed to make remarkable discoveries, among which was the legendary Ife. In the backyard of the dilapidated palace of the local ruler, Frobenius first saw pieces of a broken reddish-brown terracotta sculpture depicting a human face lying on the ground. In the following days, the expedition found or exchanged several more terracotta items from the Africans. Frobenius noticed that the locals quite easily part with the sculptures that they themselves once found in ancient sanctuaries. About clay figurines, he said: “These were traces of a very ancient and beautiful art. They were the embodiment of symmetry and refinement of form, which resembled Ancient Greece and pointed ... to the existence of a high ancient civilization».

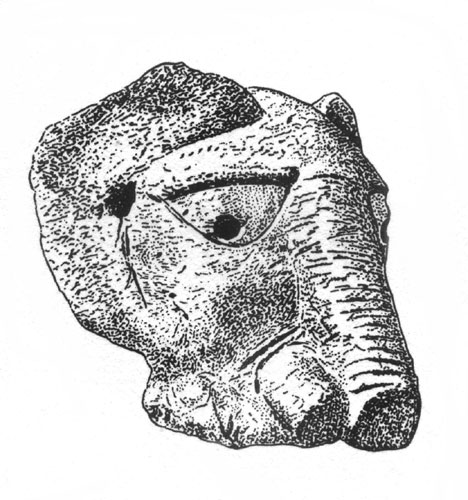

Another one significant find- bronze, no doubt very ancient and beautiful sculpture - was made by members of the German expedition in a grove dedicated to the Yoruba god of the sea Olokun. Frobenius recalled: “Before us lay a head of amazing beauty, miraculously cast in bronze, truthful in its vitality, covered with a dark green patina. It was Olokun himself, the Poseidon of Atlantic Africa."

Among other acquisitions, the gagged sculpted heads that adorned bronze vessels seemed the strangest.

The results of the German expedition made a strong impression on the scientific and even literary and artistic circles of Europe. A significant role in this was played by the fascinating books of Leo Frobenius himself - “And Africa spoke” and “Roads of the Atlanteans”. The last name is not accidental, but more on that later.

So, in the early 1990s. before academia the riddle of Ife arose. Beautiful in their perfection and completeness, bronze and terracotta realistic sculptural portraits of men and women are almost life-size. They are close in style to the antique ones, but the facial features of the sculptures from Ife are typically Negroid. Who created them and when?

How did the technique of making bronze sculptures originate in Ife? The locals could not give a satisfactory explanation to these questions. Archaeologists and art historians puzzled over the mystery of their origin. In our time, most scholars are inclined to believe that the sculptures depict local gods, kings or courtiers and, in all likelihood, originally stood on altars, where they were worshiped in the worship of ancestors.

Obviously, in ancient Ife they believed that the figure of an ancestor serves as an intermediary between the afterlife and living people. Leo Frobenius put forward his own hypothesis about the origin of the ancient civilization of West Africa, discovered in Nigeria, which has not been confirmed or refuted by anyone so far.

“I affirm,” he wrote in 1913 after archaeological research in Ife, “that the Yoruba with its lush and lush tropical vegetation, the Yoruba with its chain of lakes on the coast Atlantic Ocean, Yoruba, whose characteristics quite accurately outlined in the work of Plato - this Yoruba is Atlantis, the birthplace of the heirs of Poseidon, the god of the sea, who they called Oirkun, the country of people about whom Solon said: they extended their power right up to Egypt and the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Interestingly, Frobenius saw a “clear similarity” between the Yoruba culture and the Mediterranean culture of the ancient Etruscans, since both of them found terracotta sculptures of such perfect execution, made in a similar artistic manner. In addition, Frobenius argued that the entire Western civilization is the civilization of the Atlanteans from Britain to Libya. As for the Yoruba and Etruscans, it is still unknown where the ancestral home of these great peoples was located, so it is quite likely that it really could have been the lost Atlantis or other lands that disappeared from the face of the Earth as a result of natural disasters.

Ancient Aksum

At the beginning of the 1st century and our era, along with the great states ancient world, Rome, Egypt and the kingdoms of India flourished another, little known now, but glorified in those days, the African state of Aksum. He conquered vast territories from the Sahara to the shores of the Red Sea and even lands located on the opposite Arabian coast.

Local folklore places the appearance of Aksum in Biblical times. At that time, a giant dragon ruled in the country of Sheba - a despot and tyrant. Traditions say that he demanded from his subjects endless offerings of cattle and virgins Among the unfortunate girls who were to become victims of the tyrant, somehow there was a beauty loved by the brave young man Agaboz. To save his beloved, he killed the monster sitting on the throne, and the delivered people proclaimed him king. Agaboz was succeeded by his daughter, the beautiful Makeda, queen of Sheba. A smart, enlightened and inquisitive ruler, known in the Bible as the Queen of Sheba.

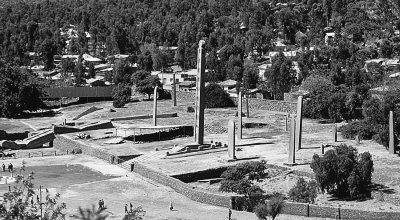

Now on central square Aksum (in Ethiopia), in the middle of a noisy bazaar, surrounded by unsightly adobe houses, giant basalt obelisks rise or lie in the dust along the road - the only remaining witnesses of their former greatness more than two thousand years ago. There are more than two hundred monoliths, giant stone columns, not similar to each other.

Stone stelae in Aksum

Some are exquisitely slender, perfectly polished, richly decorated, others are deliberately primitive and rude. Some are over thirty meters high. The length of the smallest stelae is five meters.

The origin of the obelisks (or stelae) and their purpose is still a mystery. It is not clear what technique their creators used to transport from afar and erect these multi-ton boulders. The art of Aksumite masons is all the more striking because all the stelae are carved from solid blocks of blue basalt - the hardest of the rocks.

For a long time it was believed that the steles were simply dug into the ground. In the 30s. the German-Ethiopian archaeological expedition suddenly discovered that some of them are based on huge, up to 120 meters long and up to 80 meters wide, platforms made of hewn basalt slabs. It became clear that the stelae were only the upper, crowning parts of structures truly fantastic in size, hidden under an insignificant layer of earth. Unfortunately, in 1938, at the height of the Italian aggression against Ethiopia, fascist planes bombed the ruins of majestic buildings. Only the memoirs of archaeologists who had previously been able to partially explore these structures have survived. They considered them the palaces of the Aksumite rulers - the Negus. In one of the palaces there were more than a thousand halls and beds. The floors in them were covered with green and white marble slabs, rare breeds of mahogany and rosewood; the walls were clad in polished ebony and dark marble, with gilded bronze inlays in relief. Bas-reliefs decorated windows and doors. Bronze sculpture and pottery covered with glaze and painted with intricate ornaments completed the interior of the palace.

Some researchers believe that the Negus palaces had from 4 to 14 floors! They also quite convincingly say that the bas-relief images on the steles conveyed on a reduced scale all the details of the royal dwelling. It is believed that the height of the real floor was probably 2.8 meters, therefore, the height of the 14-story palace was about 40 meters.

One of the first written references to Aksum, as, indeed, to most cities in East Africa, we find in the famous "Periplus of the Erythrean Sea" - the oldest of the sailors of the ancient world that have come down to us, written around 60 AD. e. The name of the lot speaks for itself. The Eritrean Sea is the ancient name of the Indian Ocean, and Eritrea (the territory of modern Ethiopia) is component Aksumite state.

In the 1st century Ethiopian Negus kings converted to Christianity, and Aksum became the first and most powerful Christian power in the world. The lords of Aksum saw in Christianity a force capable of uniting a country of diverse tribes and languages. They built numerous palaces and temples crowned with crosses.

In modern Aksum, one of them has been preserved - the temple of the Holy Virgin Mary, one of the main shrines of Ethiopian Christians. The square building is built of gray stones held together with clay mixed with chopped straw. The temple, built about half a millennium ago, is crowned with a small gilded dome.

The interior of the church is modest: the altar is covered with a colored veil, the columns are decorated with canvases with paintings from Holy Scripture. The floor is covered with mats, there are also wooden drums that serve as musical accompaniment during prayers and chants.

In the III-IV centuries. the Negus maintained close political and economic relations with Christian Byzantium. One of the travelers, the Greek Nonnos, the ambassador of the Byzantine emperor Justinian, left a description of the reception at the Aksumite ruler: the king in rich clothes, gold bracelets and a crown was sitting in a gold-decorated chariot drawn by elephants. In his hands were two golden spears and a shield also adorned with gold. In the presence of the king, tame giraffes were fed and court singers sang.

The Christian monarchs of Aksum minted their own coins and sent merchant ships and caravans to all countries. The Romans, Byzantines and Arabs portrayed the Aksumite kingdom as a powerful, rich and enlightened state.

In the middle of the XVIII century. Ethiopia was "rediscovered" by the Europeans. The first true explorer ancient country Scottish traveler James Bruce

At that time, the Ethiopian rulers firmly adhered to a policy of isolation. In addition to Greek merchants of the same faith, foreigners were not allowed into the country. AT last time, in 1699, the French doctor Charles Pence visited there, and less than a hundred years later, in 1769, Bruce arrived in the Ethiopian port of Massawa, and a year later, Bruce arrived in the capital of the country, Gondar.

It cannot be said that he was greeted warmly, but Bruce presented the recommendations of a doctor to the royal family and treated the queen mother and her grandchildren for smallpox, which made a very good impression. In addition, in addition to Arabic, he knew local languages and dialects. James Bruce, himself the scion of an ancient aristocratic family, did not see much difference between the London and Ethiopian courts. Only external manifestations seemed barbaric to him: feudal strife and wars; soldiers returning home with spears adorned with the entrails of defeated enemies; brutal way of carving pieces of meat from live cattle.

The longed-for goal of Bruce's travels was the source of the Nile, and already in 1770, following the Ethiopian army, he got to the Tis-Isat waterfall, through which the Blue Nile flows out of the lake.

In the summer of 1774 Bruce returned to London. About his adventures in Africa and the amazing discoveries made there, he wrote the three-volume work “Journeys to the Sources of the Nile.” This book made Bruce famous all over the world, because, in addition to geographical discoveries, the traveler told that he had brought from Ethiopia the complete manuscript of the apocryphal "Book of Enoch", until then considered irretrievably lost. The most valuable find for the history of Christianity was not accidental, because Bruce went around all kinds of churches and monasteries in Ethiopia in search of sacred relics, and it was in Aksum, in the ancient temple of the Holy Virgin Mary, that he discovered a manuscript telling about the events that followed the arrival on Earth from outer space " fallen angels" and related "wonderful visions" of the biblical patriarch Enoch.

It is possible that Bruce's interest was caused not only by his religiosity. He was a member of an old Scottish Masonic lodge, which turned to the mystical secret teachings of the past, and the Book of Enoch justified all his hopes in the best possible way, and more than one generation of Christians has been thinking about its sacred meaning since then.

The discovery caused a sensation, because its significance is comparable to the discovery of the Qumran scrolls in the Dead Sea, or, moreover, with another hitherto unknown part of the Bible.

Article 4

Article 3

Article 2

Article 1

Extracts from the Declaration of the Rights of Culture

Text No. 15

In this Declaration, culture refers to the material and spiritual environment created by man, as well as the process of creating, preserving, disseminating and reproducing norms and values that contribute to the elevation of man and the humanization of society. Culture includes:

a) cultural and historical heritage as a form of consolidation and transmission of the total spiritual experience of mankind (language, ideals, traditions, customs, rituals, holidays ... as well as other objects and phenomena of historical and cultural value);

b) social institutions and cultural processes that generate and reproduce spiritual and material values(science, education, religion, professional art and amateur creativity, traditional folk culture, educational, cultural and leisure activities, etc.);

c) cultural infrastructure as a system of conditions for creating, preserving, exhibiting, broadcasting and reproducing cultural values, developing cultural life and creativity (museums, libraries, archives, cultural centers, exhibition halls, workshops, the system of management and economic support of cultural life).

Culture is a determining condition for the realization of the creative potential of the individual and society, a form of asserting the identity of the people and the basis of the mental health of the nation, a humanistic guideline and criterion for the development of man and civilization. Outside of culture, the present and future of peoples, ethnic groups and states lose their meaning.

The culture of every nation, large and small, has the right to preserve its uniqueness and originality. The whole set of phenomena and products of the material and spiritual culture of the people constitutes an organic unity, the violation of which leads to the loss of the harmonious integrity of the entire national culture.

The culture of every nation has the right to preserve its language as the main means of expressing and preserving the spiritual and moral identity of the nation, national identity, as the bearer of cultural norms, values, ideals.

Participation in cultural life is an inalienable right of every citizen, since a person is the creator of culture and its main creation. Free access to cultural sites and values, which by their status are the property of all mankind, must be guaranteed by laws that eliminate political, economic and customs barriers.

1. Name three major structural elements of culture highlighted in the text. (Write out the titles, rather than rewriting the corresponding piece of text in its entirety.)

2. The text names the social institutions that create, preserve and transmit cultural values. Name any two and give an example of the values each works with.

3. The text characterizes the attitude of a person to culture. Using the facts of public life, personal social experience, illustrate with two examples the statement that: a) a person is a creation of culture; b) a person is a creator of culture. (In total, there should be four examples in a correct full answer.)

4. Using the text, social science knowledge and facts of public life, give two explanations for the connection between the preservation of the national language and the preservation of national identity.

5. Give a title to each of the following articles of the Declaration.

6. The Declaration affirms that culture is the foundation of the mental health of a nation. Using social science knowledge and personal social experience, give two proofs of this.

Text No. 16

When the first African sculptures came to Europe, they were treated as a curiosity: strange crafts with disproportionately large heads, twisted arms and short legs. Travelers who visited the countries of Asia and Africa often talked about the inharmoniousness of the music of the natives. The first prime minister of independent India, D. Nehru, who received a brilliant European education, admitted that when he first heard European music, it seemed to him funny, like birdsong

In our time, ethnic music has become an integral part of Western culture, as well as Western clothing, which has replaced traditional clothing in many countries of the world. At the turn of the XX-XXI centuries. obviously a strong influence of African and Asian decorations.

However, the spread of non-traditional philosophical views and religions is much more important. For all their exoticism, despite the fact that their acceptance is often dictated by fashion, they affirm in the minds of society the idea of the equivalence of ethnic cultures. According to experts, in the coming decades, the trend towards interpenetration and mutual enrichment of cultures will continue, which will be facilitated by the ease of obtaining and disseminating information. But will there be a merger of nations as a result, will the population of the planet turn into a single ethnic group of earthlings? There have always been different opinions on this matter.

The political events of the late 20th - early 21st centuries, associated with the separation of ethnic groups and the formation of nation-states, show that the formation of a single humanity is a very distant and illusory prospect.

1. What was the attitude of Europeans to the works of other cultures in former times? What has it become in our time? Using the text, indicate the reason for maintaining the trend towards interpenetration and mutual enrichment of cultures.

2. In your opinion, is the prospect of turning the planet's population into a single ethnos of earthlings realistic? Explain your opinion. What is the danger of realizing this prospect?

3. What manifestations of the interpenetration of cultures are given in the text? (List four manifestations.)

4. Some countries set up barriers to the spread of foreign cultures. How else can an ethnic group preserve its culture? Using social science knowledge, the facts of social life, indicate three ways.

5. Plan the text. To do this, highlight the main semantic fragments of the text and title each of them.

6. Scientists believe that the progress of technology and technology contributes to the interpenetration of cultures. Based on personal social experience and the facts of public life, illustrate this opinion with three examples.

Text No. 17

The main manifestation of the moral life of a person is a sense of responsibility towards others and oneself. The rules by which people are guided in their relationships constitute the norms of morality; they are formed spontaneously and act as unwritten laws: everyone obeys them as they should. This is both a measure of society's requirements for people, and a measure of reward according to merit in the form of approval or condemnation. The right measure of demand or reward is justice: the punishment of the offender is just; it is unfair to demand more from a person than he can give; there is no justice outside the equality of people before the law.

Morality presupposes relative freedom of will, which provides the possibility of a conscious choice of a certain position, decision-making and responsibility for what has been done.

Wherever a person is connected with other people in certain relationships, mutual obligations arise. A person is motivated to fulfill his duty by his awareness of the interests of others and his obligations towards them. Beyond knowledge moral principles it is also important to experience them. If a person experiences the misfortunes of people as his own, then he becomes able not only to know, but also to experience his duty. In other words, a duty is something that must be performed for moral, and not for legal reasons. From a moral point of view, I must both perform a moral act and have a corresponding subjective frame of mind.

In the system of moral categories, an important place belongs to the dignity of the individual, i.e. awareness of its social significance and the right to public respect and self-respect.

(According to the materials of the encyclopedia for schoolchildren)

1. How does the author characterize the norms of morality? (Give three characteristics.)

2. The newspaper published untrue information discrediting citizen S. He filed a lawsuit against the newspaper for the protection of honor and dignity. Explain Citizen C's actions. Give a piece of text that may help you explain.

3. The text notes that in addition to knowing moral principles, it is also important to experience them. Based on the text, your own social experience, the knowledge gained, explain why moral feelings are important (name two reasons).

4. Plan the text. To do this, highlight the main semantic fragments of the text and title each of them.

Text No. 18

Culture is often defined as "second nature". Cultural experts usually refer to culture as everything man-made. Nature is made for man; he, working tirelessly, created the "second nature", that is, the space of culture. However, there is a flaw in this approach to the problem. It turns out that nature is not as important for a person as the culture in which he expresses himself.

Culture, first of all, is a natural phenomenon, if only because its creator, man, is a biological creature. Without nature, there would be no culture, because man creates in the natural landscape. He uses the resources of nature, reveals his own natural potential. But if man had not crossed the limits of nature, he would have been left without culture. Culture, therefore, is an act of overcoming nature, going beyond the boundaries of instinct, creating something that can be built on top of nature.

Human creations arise initially in thought, spirit, and only then are embodied in signs and objects. And therefore, in a concrete sense, there are as many cultures as there are creative subjects. Therefore, in space and time there are different cultures, different forms and centers of culture.

As a human creation, culture surpasses nature, although its source, material and place of action is nature. Human activity is not entirely given by nature, although it is connected with what nature gives in itself. The nature of man, considered without this rational activity, is limited only by the faculties of sense perception and instincts. Man transforms and completes nature. Culture is activity and creativity. From the origins to the sunset of its history, there was, is and will be only a “cultural person”, that is, a “creative person”.

(According to P.S. Gurevich)

1. The writer decided to create a novel about the life of his contemporaries. At first, he built the main storyline for several months. After the writer decided on the images of his characters, he set to work, and a year later the novel was published. Which piece of text explains this sequence of actions? What type of art is represented in this example?

2. Plan the text. To do this, highlight the main semantic fragments of the text and title each of them.

3. What approach to the definition of culture is discussed in the text? What, according to the author, is the disadvantage of this approach?

4. How does the author characterize the relationship between human nature and his activities? What, in his opinion, is the content and result of the activity?

5. Why, according to the author, “without nature there would be no culture”? Give two answers of the author and illustrate with an example each of the answers.

6. The author uses the phrase "man of culture" in a broad sense. What kind of person in modern conditions, in your opinion, can be called a cultured person? What do you think parents should do in order for their child to grow up as a cultured person? (Invoking social science knowledge and personal social experience, indicate any one measure and briefly explain your opinion.)

So far, only a few examples of sculpture have been found in the main areas of distribution of rock art. In the form in which it exists in Tropical Africa, sculpture is almost never found among peoples leading a mobile lifestyle. It is not present among modern Fulbe, Tuareg and other nomadic pastoralists - inhabitants of the savannah ( But in the ornamental forms of applied arts practiced by them (artistic processing of leather and fabrics, weaving, etc.), very ancient graphic and pictorial traditions are preserved.). Indicative in this sense are the Bushmen, nomadic in the desert and semi-desert regions of South Africa. Their rock paintings and polychrome drawings adorning household items testify to the developed artistic traditions, but sculpture among the Bushmen is completely absent.

The natural and climatic conditions of the tropics, which are extremely unfavorable for cattle breeding, determined the development of other forms of economic activity.

Agriculture, which became the basis of the economy here, determined the formation of an appropriate social structure and the entire tribal material and spiritual complex. If in the Sahara fine art is represented by painting and petroglyphs, then in other conditions sculpture becomes the main type of fine art. It can be thought that the predominant development of sculpture here was associated not so much with the abundance of soft woods (from which most African masks and figurines were made), but with the widespread introduction of pottery, accompanying agriculture. What ancient sculpture Tropical Africa, currently known, is made of fired clay, perhaps due not only to the relative durability of this material.

The map of the distribution of sculpture in Tropical Africa generally corresponds to its ethnic geography, since sculpture existed everywhere here. Quite clearly defined contours, within which schools of traditional sculpture are grouped, correspond to the profile of the western coast south of Guinea and the lower reaches of the Niger and Congo with its many tributaries. The northern border of the distribution of the sculpture coincides with the upper bend of the Niger (to the north - only the Bambara), the eastern border passes through the Great Lakes region, and the southern one - through the territory of Angola. The most compact group is formed by the art schools of the peoples of southern Nigeria, inhabiting the lower reaches of the Niger and Benue rivers.

The bulk of traditional sculpture is made up of wooden products - figurines, masks, and applied arts. Since the tree in the tropics survives only for a very limited time, stone, bronze and terracotta sculptures found in certain areas of Tropical Africa, sometimes as a result of targeted searches, but more often by chance, are of particular value for stylistic analysis. The history of these, unfortunately, few discoveries is indicative, since it gives an idea of difficult problems resulting from such findings.

"Afro-Portuguese" plastic

Among the old monuments is, in particular, "Afro-Portuguese" - plastic - the first African sculpture, which Europeans met. Currently, the largest collection of "Afro-Portuguese" plastics (more than twenty products) is in the British Museum. Individual items are kept in the Cluny Museum (Paris), the Nigerian Museum (Lagos), the Dresden Ethnographic Museum, the Portuguese National Museum (Lisbon) and in private collections. Copies of oliphants (ivory pipes) are in the Hermitage collection. When analyzing this sculpture, it must be taken into account that it does not belong to the usual traditional products and, perhaps, is a by-product of the court art of one of the medieval states of West Africa. The abundance of European plots, the purpose and the special form of these products indicate that they were made for export, by order of Portuguese merchants. At the same time, elements of ornament and even individual images can be found, which should be considered as typical of the art of that time. Even if there are relatively few such details, they are of great value, since this is one of the rare cases when we are dealing with dated monuments of African art (Fig. 19).

Rice. 19. Salt shaker. Ivory. "Afro-Portuguese" plastic. British Museum, London

Early publications (260, 210) do not question the Benin origin of this sculpture. By 1959, the collection of the British Museum was thoroughly studied and published in full in the album W. Fagg, W. and B. Foreman (195). In the introductory article W. Fagg points out some stylistic parallels between "Afro-Portuguese" sculpture and steatite figurines from Sierra Leone ("nomoli"). As other possible origins of this sculpture, Fagg names the Loango area at the mouth of the Congo, as well as the cities of Lagos (Nigeria), Porto Novo and Uida (former Dahomey, now People's Republic Benin), rightly noting its stylistic affinity also to Yoruba sculpture (masks "gelede", figurines of twins "ibeji"). At the same time, Fagg sees no similarities between the "Afro-Portuguese" Ibenin sculpture. Fagg, in particular, bases his conclusion about the non-Benin origin of these products on the fact that he failed to find "not a single thing, not a single fragment that would be found in Benin ..." (195, XX). However, all currently known items of Benin court art were exported to Europe in 1897, while the sculpture in question was made in the 16th century by order of Portuguese merchants and, presumably, was entirely exchanged for European goods. As for the stylistic parallels with the art of the Yoruba, this circumstance, at best, can once again remind of the well-known links between the Bini and the Yoruba in the heyday of the states of Ife and Benin. But at the same time, one should not lose sight of the significant chronological divergence of stylistic parallels noted by Fagg: in one case we have fine ivory works of applied art of the 16th century, in the other we have iconic wooden masks and figurines of the 19th-20th centuries.

Art of Ife

The discovery at the beginning of our century of the now famous art of Ife gave rise to many different hypotheses. Incomparable to anything known at that time, the naturalistic style and perfection of bronze casting seemed to indicate some kind of isolated and alien culture. At the same time, a pronounced local ethnic type, captured in bronze and terracotta portraits, indicated that we can only talk about local culture, which experienced some external influences to one degree or another. The Portuguese, Carthaginians, Nubians, etc. were named as possible agents of these influences. Frobenius considered Ife to be the center of an ancient powerful empire - the legendary Atlantis, the memories of which were preserved in the form of legends after its connections with outside world were completely interrupted. At the time of Frobenius, a relatively small number of monuments of Ife art were known. Since then, thanks to a series of finds that have greatly expanded our understanding of the ancient history of the Yoruba people, it has become clear that we are talking about a really powerful center of culture, which had a noticeable impact on vast territories north and east of the Niger Delta. Among the peoples inhabiting adjacent territories, one can still find elements of Yoruba religious beliefs, their artistic traditions, and social organization.

Since about the 16th century, Ife has been losing its political influence. However, to this day, this city is considered the sacred center of the Yoruba country. According to the mythological ideas of the Yoruba, Ife is the center of the earth, from where it originates. According to myths, it was here that the creation of all things began by the powerful deity Odudua, who was the founder of the city and the founder of the dynasty of Ife rulers.

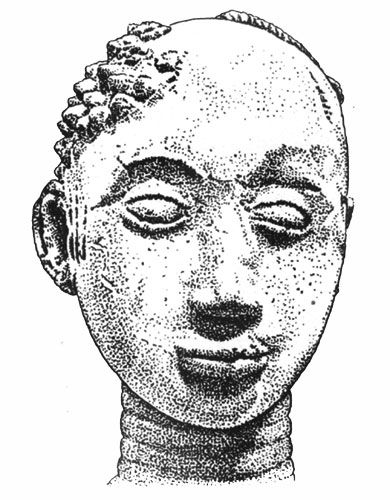

One of the first pieces of Ife art to be seen in Europe was a quartzite throne brought to the British Museum in 1896. This throne, shaped like the wooden seats of Beninese chiefs, attracted little attention. As a completely new phenomenon, the art of Ife was discussed only in 1905, after a plaster cast of one of the terracotta heads was exhibited in the British Museum (ill. 72, 73).

The study of Ife art began after the Frobenius expedition in 1910, during which terracotta heads and torsos and a large bronze head, now known as the head of Olokun, were found. In addition, the expedition discovered quartz art, crocodile figurines, various items- from large stools to elegantly finished handles. The next big discovery was made in 1931 in the sacred grove of Invirin, near Ife: eight terracotta heads and dozens of sculpture fragments. In 1938, seventeen more bronze heads and a bronze statue were discovered on the site of the palace of the Oni, the ruler of Ife, which once existed here.

In 1949, in the town of Abiri, fifteen kilometers from Ife, B. Fagg found a new sculpture. This time among the terracotta sculptures, along with a typical Ifa realistic portrait, there were extremely schematic anthropomorphic images. Moreover, of the seven heads found in one burial, four are extremely arbitrary (a cone and a cylinder with barely outlined schematic images of the eyes and mouth) and three are extremely realistic. During the same excavations, images of a coiled snake and a ram's head were found.

In 1953, as a result of systematic excavations in the Ife region, along with the remains of a ceramic pavement, many decorations, fragments of sculpture, and several terracotta heads were recovered. One of the most valuable finds was made in 1957 in Ife, in the Ita-Iemuu region. Among other bronze items, a well-preserved full-length figure of Oni Ife was found here. ceremonial clothes(fig. 20, ill. 68).

By the beginning of the 70s, more than sixty works of Ife art were already known. This collection of first-class bronze and terracotta sculptures includes life-size portraits of the rulers of Ife, statues and half-figures, scepters, armchairs, and animal figures. (History of discoveries in Ife - see: 18.)

A special place among the monuments of ancient art of Ife is occupied by stone statues from the sacred grove of Ore. This grove is located one kilometer from the city center. A path leads to it, framed by vertically standing stone blocks. The path leads to small clearings on which statues stand. One of them is a squat figure in a loincloth, with his hands folded on his stomach; another, smaller, in the same pose and style, resembles a dwarf; the third is a kneeling figure, with hands pressed to the chest, of a slightly different style - considered to be later than the previous two. These statues are very rarely mentioned in connection with Ife art. The time of their creation is unknown, the origin is debatable. Local experts - Nigerian archaeologists and ethnographers - believe that they were created earlier than all the known monuments of Ife, and that their authors are, perhaps, not the Yoruba, but the more ancient local population - the Igbo people. According to another assumption, they could be created by the first Yoruba settlers. J. Delange believes that the style of these stone statues is similar to the style of terracotta figurines found in West Africa (123, 83).

Among the ensembles of old Nigerian art, small bronze plastic remains a mystery, about which it is known only that the place of its origin is the lower reaches of the Niger River. Hanging anthropomorphic bells, bracelets with images of masks, ritual zoomorphic figurines, bottles, goblets, masks and other objects of art are very diverse in style, however, they have something in common not only in the nature of the products, material, casting technique, but also in the actual artistic features. A group of bronze items recovered from excavations on the left bank of the Niger, in the Igbo village of Ukwu in 1959-1960 and 1964, also reveals common stylistic features: a kind of "Baroque" in the decoration of bronze vessels and jewelry, the widespread use of the finest grain and brass wire for complex ornamentation and creating a special texture. Sculpture of the lower Niger dates very roughly from the 8th to the 12th century. n. e.

Adjacent to the art complex of Ife, and perhaps also Benin, is a terracotta sculpture from Ovo, located 100 km from Benin and 110 km from Ife. Excavations carried out here for the first time in 1969 by the Nigerian archaeologist Ekpo Eyo yielded curious materials, including magnificent examples of sculpture. Most of the sculptural fragments from Ovo have an undoubted resemblance to the style of Ife terracotta sculpture, while others reveal features characteristic of the art of Benin; some things - for example, the head of a bearded man - are distinguished by expression, great originality.

The sculpture from Ovo dates from around the 15th century.

In 1934 ( According to other sources - in 1933. This discovery was made by Catholic mission teacher G. Ramshaw. First published in 1938 (258)) sixty-five kilometers north of Ife, near the village of Eziye (province of Ilorin), more than eight hundred stone heads and figurines were found. All this steatite sculpture, discovered in a forest clearing, is now stored on a special altar, and in March, before the start of field work, the local population arranges annual festivities here in honor of the patron spirits of the local community. Although these monuments are not equal in execution and obviously belong to more than one master, they represent a monolithic stylistic group - and the largest group of stone sculpture in Tropical Africa. The age and origin of these monuments are unknown. According to W. Fagg, J. Delange and others, its authors may have been Nupe, who created this sculpture before they were forcibly converted to Islam. According to D. Polm, its age does not exceed three centuries, according to other sources, it is contemporary with the classical period of Ife (XII - XIV centuries AD). Although Eziye's sculpture cannot be definitely assigned to any known circle of monuments, there are sufficient grounds to consider the possibility of its connection with the culture of Ife. Moreover, the similarity exists not only with the classical bronze and terracotta sculpture, but also with stone statues from the Ore grove. With regard to the technique of execution of this sculpture, it should be noted that Fagg's opinion regarding its connection with woodcarving is unconvincing. The soft, swollen forms of the seated figures, the interpretation of facial features - eyes, nose, mouth - and especially the filigree forms of bracelets and necklaces (see: 143, pl. 74-76) are just as close to the technique of Ife bronze casting and chasing, as well as to the modeling of the terracotta sculpture Nok (Fig. 22, ill. 69, fig. 21).

Sculpture Nok

The discovery of the latter by the English archaeologist B. Fagg should be recognized as the largest contribution to the study of the history of African art. With the discovery of the Nok culture, the chronological retrospection of African sculpture deepened for a whole millennium.

Since 1911, various ancient tools have been found in tin mines in northern Nigeria (Bauchi Plateau). As a result of such accidental finds, a solid collection of polished stone axes and microliths has gathered in the local museum of the city of Jos. The first sculptures were discovered in 1931, but only in the spring of 1944 a discovery was made (near the village of Nok), which served as the beginning of systematic excavations. Now, as a result of many years of archaeological research, it has been established that we are talking about a developed unknown culture from the very beginning of the Iron Age ( Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding Nubia and Mauritania) went directly from stone to iron, bypassing bronze. In the region of distribution of the Nok culture, the transition to iron occurred no later than the 3rd century BC.).

Extended studies made it possible to clarify the boundaries of the distribution of this culture, which existed on a vast territory, the total area of \u200b\u200bwhich, according to the latest data, is about five hundred kilometers from west to east and more than three hundred from north to south. Typical examples of the Nok culture, first found in the southern part of northern Nigeria, have been found in many other places.

With a few exceptions, terracotta sculptures and other items have been found in open pit mines. A careful examination of the rock thrown out of the mines showed that since the development of the mines began, many priceless works of art have been thrown to the surface along with the earth. Unfortunately, only a very small part of them has been completely preserved: the bulk of the sculpture is fragments of statues and heads. The statues, and especially the heads, are comparatively well preserved due to their compact round shape (ill. 70, 71).

The scientific value of these discoveries has especially increased due to the fact that the deposits in which the Nok sculpture was found could be dated quite accurately using the C-14 method, since a tree trunk cleared of bark was found in the layer containing the sculpture; radiocarbon analysis of it gave a date - 900 BC. e. The layer covering the deposits in which the sculpture was found has been dated to 200 AD. e. Given these circumstances, and taking into account information about the time of the appearance of iron in West Africa, as well as some features of local geological processes, the Nok culture is dated from 500 BC. e. before 200 AD e (Fig. 23).

Thus, the terracotta heads and figures of Nok are the oldest sculptural monuments of West Africa known at present. A whole millennium separates them from the art of Ife and two millennia from the examples of traditional plastics that have survived to this day. It would seem that such an impressive gap in time makes a comparative stylistic analysis of the Nok and Ife sculptures unpromising, but this is not so.

In the absence of direct analogies with known sculptural styles, Nok terracottas have some very significant features characteristic of late traditional sculpture. First of all, this is an amazingly rich arsenal artistic techniques. Carefully examining dozens of heads, figurines and various sculptural fragments, one can notice that, despite the stylistic unity that makes it possible to unmistakably distinguish the Nok sculpture from any other, it is devoid of the stencilling that marks, for example, Benin sculpture.

The large Nok head is distinguished by a luxuriant hairdo, sharply defined cheekbones, and a facial expression that conveys extreme tension. The other, from Jemaa, is equally expressive and realistic in style, depicting a man with a high, prominent forehead, large, wide open eyes and a characteristic, as if carved with a knife line of the mouth. Hair resembles a tightly worn wig, a strongly raised upper lip rests on the lower part of the nose. A slightly different style is the head of a bearded man found near Kagara. Other in style and technique are also small terracotta heads belonging to the so-called "long-eared" group. Their modeling is more soft, smooth transitions. A round convex forehead occupies half of the face, the nose is short and flattened, a small, beak-like mouth and a barely outlined chin. Such a decrease in proportions from top to bottom, which is generally one of the features of African sculpture, is characteristic of all sub-styles of Nok sculpture and is observed not only in the modeling of the face, but also in human figures, such as, for example, the statuette of a kneeling man from Abuja (the head size is more half of this sculpture, and the proportions of the face are the same as those of the head from the "long-eared" group).

The sizes of the heads are as different as their shape - they range from a few centimeters to life size. Perhaps the heads are fragments of statues. Judging by the decreasing proportions of small, completely preserved figurines, from top to bottom, the size of such statues could reach one meter. (One of the figures, which was restored in parts, turned out to be just such a height.) As W. Fagg rightly notes, "this tendency to exaggerate the size of the head - as the main receptacle of vitality - was firmly established in African art already two thousand years ago, and this fact confirms the point of view that African sculpture is original and has nothing to do with the influence of white aliens" (143, 23).

The well-known similarity of Nok sculpture with traditional African sculpture is manifested, as we have already noted, in the variety of plastic interpretation of images, which can vary from realistic to extremely schematic. The human head is depicted as a ball, cylinder, cone; there are also quite unusual sculptures - twisted in the form of a spiral (see: 146, 8-9) (ill. 75).

The interpretation of individual details is just as varied. Ears, for example, often only marked with a slight indentation, sometimes take on a bizarre, elongated shape and reach a very large sizes. Only one fixed external feature unites almost all Nok heads - this is the way the eyes are depicted. The eyes of terracotta heads have a deeply drilled pupil, a more or less straight upper eyelid, and a lower eyelid that forms an isosceles triangle together with the upper eyelid. The same unity is preserved in the interpretation of the eyebrows, as if superimposed on top in the form of a braided cord. In West Africa, there is only one modern art school, in the art of which there are analogies to this phenomenon, the traditional sculpture of the Yoruba people. Similarities between Nok sculpture, on the one hand, and some centers of medieval and traditional Nigerian art, on the other hand, were noted by B. Fagg (275). Striking results were obtained by comparing two sculptures, one of which, bronze, was found in Benin (belonging to the Ife style), and the other, terracotta, in Jemaa (Nok culture). Not only are the sizes and proportions of these figures the same, but also the nature of the modeling and the interpretation of individual details. Even the decorations in the form of a belt and a necklace are almost exactly the same on both statues.

The question of which of the peoples of West Africa belongs to the Nok culture remains open. The author of the finds, B. Fagg, believes that the creators of this sculpture were "the ancestors of those tribes that currently live in the central region of Nigeria." Noting the proximity of Nok art to the art of modern peoples inhabiting the hills of central Nigeria, W. Fagg points out that, like these peoples, the creators of the Nok culture were both farmers and hunters and inhabited the entire territory where this culture is widespread. “It is quite probable,” writes W. Fagg, “that many modern tribes have preserved the same religion that flourished during the Nok culture, the cult of the mythical ancestors of the tribe, who were presented as the main source of life force, as mediators through which this force was distributed to the living We have enough reason to assume that the Nok terracotta figurines performed the same function ... as the wooden (and sometimes terracotta) figurines of ancestors, which may be descendants of the Nok culture "(143, 24).

In addition to terracotta heads, figures of various sizes decorated with ornaments, animal images (including the head of an elephant, a figurine of a squatting monkey), hand and foot bracelets, pearl jewelry, polished stone axes and adzes were found in the deposits of the Nok culture. (There is even one terracotta figurine holding such stone ax mounted on the handle.) (Fig. 24, ill. 71).

Apparently, the Nok sculpture cannot be considered as original. Not only its style, very far from primitive naturalism, artistic skill and a high degree of convention, but also the remarkable technical perfection, manifested in the features of its texture, wall thickness and quality of firing, suggest a long period of development that preceded the appearance of this culture.

Since at present only a very limited number of monuments of traditional art created before the 19th century are known, all groups of sculpture made of durable materials - stone, metal, terracotta - deserve attention.

In addition to the above, there are several more types of old stone sculpture in Tropical Africa. These are the so-called pomdos in Guinea, nomoli in Sierra Leone, mintadi in Zaire (Matadi region), akvanchi (ekoy monuments) on the border of eastern Nigeria and Cameroon.

pomdo

Pomdos are small, mostly anthropomorphic figurines carved from soft stone, which are found in the ground during the cultivation of the fields by Kisi and Mende farmers. Individual figurines are so naturalistic that, based on various details of clothing and weapons, they could presumably be dated to the 16th century. Others are highly stylized and close to purely geometric shapes. Sometimes the figurine is a simple cylinder on a rectangular stand. Kisi and Mende place these figures on altars and use them in their rites. The Kisi consider them to be the ancestors who returned from the land of the dead, the Mende consider them the patrons of the fields. A common feature of this sculpture is its vertical shape and archaic smile (Fig. 25).

Nomoli

The Nomoli of Sierra Leone are the closest relatives of this sculpture. They differ from pomdo in more rounded, soft forms. If the pomdo figures, as a rule, fit into a cylinder, then the shape of the nomoli is closer to spherical, and the axis of the composition gravitates towards the horizontal. The faces are characterized by thick lips and wide noses. The poses are varied, most often the figures are depicted at rest: they sit with their chin propped up, they lie cross-legged. Like the pomdo, this sculpture is inherited from the past. Perhaps it was made by the ancestors of modern Sherbros, who keep these figurines on home altars and make sacrifices to them in case of a harvest, but if the harvest is bad, these figurines are broken. W. Fagg believes that there is some stylistic similarity between this sculpture and "Afro-Portuguese" sculpture. J. Delange compares one figure with the bronze statues of Ife and finds that her decorations resemble the rich decoration of these statues (Fig. 26, ill. 77).

mahan yafe

The nomoli circle includes stone heads and figures (the so-called mahan yafe) discovered in Sierra Leone, on the territory of mines in the kono habitat. K. Dittmer, who studied this sculpture, believes that it precedes the statuettes described above and is an early stage in the development of the nomoli style. Approximate dating of mahan yafe - XIII century AD. e. (130) (ill. 76).

Mintadi (ntadi)

At the end of the 17th century, the Catholic missionary, Jesuit Athanasius Kircher, collected a collection of stone sculptures (mintadi) in Africa, which is currently stored in Rome, in the Luigi Pigorini Museum. Four figurines of this collection were taken from the Congo in 1695. Just like pomdo and nomoli, mintadi are carved from soft stone - steatite. Like nomoli, they convey a state of rest. Most often, the figures sit cross-legged, leaning slightly bowed head on the hand. However, there is no stylistic similarity between Mintadi and Nomoli. Mintadi style is distinguished by its angularity, clear, dry faceting of forms. The proportions are arbitrary, the hand supporting the head can be unnaturally elongated, the legs shortened. All attention is focused on the head, as is customary in traditional sculpture. But, unlike the latter, the composition is asymmetric, static is broken. There is only some resemblance to anthropomorphic fetishes. Perhaps this similarity is to some extent determined by the functions of the figures. If fetishes play the role of guardians of dwellings and crops, then mintadi are guardians of dwellings and graves ("n" tadi "in the Kikongo language - "guardian") and at the same time - images of dead leaders (ill. 78, fig. 27).

Currently, several hundred mintadi figurines are known. They were made from about the 16th to the 19th century by the Mbomba people and other Bakongo people who inhabit the Loango region in the lower reaches of the Congo River, near the northern border of Angola. The tradition of their manufacture, apparently, dates back to the era of existence ancient state Congo (see: Annex 4).

Akvanchi

One of the major discoveries of stone sculpture in Tropical Africa was made in the headwaters of the Cross River on the border of eastern Nigeria and Cameroon. About three hundred monumental basalt statues were found here. Anthropomorphic images (akvanches) carved on phallic-shaped stone blocks are, apparently, tombstones of the leaders of the Ekoi. The custom of erecting a monument after the death of the leader was preserved here until the end of the 19th century. The oldest tombstones were probably installed about three or four centuries ago. The materials published so far allow us to note the presence of at least two types of images. One of them is close to a round sculpture, the other - to a small relief and anti-relief. Monuments made in the technique of relief are more conventional, but they exactly repeat the main drawing of a round traditional sculpture, schematically, almost graphically denoting facial features, a pointed beard, neck, shoulders, a tattoo, arms folded on the stomach. Comparison of this sculpture with traditional sculpture makes it possible to identify some of the prototypical elements of the latter (ill. 79, 80, fig. 28).

sao sculpture

One of the most significant in terms of abundance and diversity of ancient art monuments is a complex cultural complex discovered by archaeologists in the area of Lake Chad. Research on the southern shore of the lake was started back in the 1920s by English archaeologists and continued since 1936 by a French archaeological group led by J.-P. Leboeuf. Under the low hills on the southern and southeastern shores of the lake, where the modern population performs annual initiation rites, the ruins of the ancient cities of the legendary Sao people were discovered. Sao is the name given to various Negroid peoples who, according to recent data, have inhabited the area since about the 5th century BC. e. area south and southeast of Lake Chad. Various articles made of copper, bronze, iron, stone, bone, mother-of-pearl and terracotta found here during many years of excavations are of particular scientific value, since most of the objects were dated by radiocarbon dating. It has now been established that the materials of the Sao culture belong to three different periods. The first period, conventionally called Sao I, corresponds to the settlements of ancient hunting tribes that appeared here no later than the 10th century AD. e. The second (Sao II) covers the period between the 11th and 14th centuries and is associated with the settlements of fishermen. In some places, this period lasted until the 18th century. Items found in the upper layers of the Sao culture, belonging to the last, shortest period, date back to the 19th century.

Sao art is represented mainly by terracotta sculpture, conventionally divided into two groups - human images and images of animals. However, even such a simple division cannot be clear enough, since most of the sculpture is either zoomorphic human images or anthropomorphic animal images. There are also those in which the features of an animal and a person cannot be differentiated. Regardless of the nature of the image, the entire sculpture is divided into heads and figurines (ill. 81-84).

An understanding of the style and general character of this unusual sculpture can be helped by its comparison with the terracotta sculpture of Nok. Unlike Nok, there are very few naturalistic images among the sao sculptures, although otherwise its stylistic diversity is not only not inferior to Nok sculpture, but also significantly exceeds it.

Most of the sao terracotta heads are made in a peculiar schematic style, which can be conditionally called decorative. The nose, mouth and eyes seem to be superimposed on a flat or slightly convex plate, often oval in shape. There is almost no forehead, the eyes are shifted to the bridge of the nose, the shape of the mouth repeats in an enlarged form the shape of the "coffee bean" characteristic of the interpretation of the eyes. The lower part of the face, which passes into the base - the stand of the sculpture, is not developed in any way. Graphic and stucco decorative elements in the form of a geometric ornament or incisions are most often concentrated in the upper part of the face and, possibly, reproduce the tattoo design. Heads in the shape of an egg, a disk, a triangle rest on a small plinth, which serves as a direct continuation of the lower part of the head. The details of the face are either stuck on or painted on a plane, which indicates the presence of graphic and, possibly, pictorial traditions. From this point of view, the head from the village of Tago is very interesting. Its smooth convex surface bears almost no traces of molding. The nose is indicated by two deeply incised lines crossing the face from the top of the forehead to a transverse fissure marking the position of the mouth. The eyes, which are much lower than their real location, are barely outlined by slight bulges. Double, incised grooves above them, together with the line of the nose, form a pattern resembling the shape of an arrow.

An example of a less schematic depiction is the head of a so-called deified ancestor found in the same village of Tago. The interpretation of the head is much closer to the actual sculptural one. A beard in the form of a trident hides a short neck, a huge mouth crosses the face from ear to ear; under the narrow strip of the forehead there are empty black slits near the closed eyelids. This "coffee bean" eye shape is found in most sao sculptures. Thus, here, as in the Nok sculpture, the eyes are the only unified element that, along with other, less pronounced formal features, makes it possible to identify some common stylistic features of the sao sculpture.

Comparing the heads of the sao with the heads of the Nok, one can see one interesting feature: if in Nok heads the forehead is disproportionately large in relation to the rest of the face, then in the sao sculptures the forehead is almost completely absent in most cases, but the rest of the face is disproportionately enlarged and maximum attention is paid to its modeling.

The time of the highest flourishing of the "clay culture" falls on the XII - XVIII centuries. In the art of this time, a special place is occupied by large three-quarter statues. Judging by individual finds, these statues were placed in sanctuaries. Part of one of these sanctuaries has been preserved in its original form. The central place on the altar was occupied by three large figures, which, according to Leboeuf, were revered as images of the founder of the city and his descendants and symbolized the power of the first leaders. One of the figures is clearly male, the other two are possibly female.

The figures are made of finely sifted clay, their texture is carefully processed. A zigzag ornament is applied to the wet clay surface with a sharp tool. With the exception of the ornament and small bulges on the chest and in the center of the abdomen, the torso of the figure is devoid of any modeling whatsoever. In essence, it is a plinth - a sculpture stand. The arms of the figure are barely indicated by short, awkward processes, the shoulders are very wide, square, disproportionately large in relation to the head, in the interpretation of which the sculptor follows a strict canon that accurately determines the shape and position of individual parts. There are no hints in the face individual characteristics specific person. His features seem to be simply listed, and the artist seems to be most concerned with making it easier for the viewer to recognize every detail. Thick lips, crossing the face at right angles, strongly pushed forward. The same protruding square mass marks the position of the chin. The long, straight nose lies in the same plane as the mouth and chin; only the narrow line of the forehead is turned at a slight angle towards the viewer. The "coffee bean" shaped eyes lack sockets and are not structurally related to their natural location. An ornamented image of a snake stands out in relief on the neck, which apparently has a symbolic meaning (Fig. 29).

In addition to these figures depicting deified ancestors, three-quarter statues were found in the sanctuary, which are considered to be figures of masked dancers. These figures are somewhat different from the previous ones. The same flat torso, but this time with narrower sloping shoulders; the same schematism in the interpretation of the face, only the chin does not protrude forward, but is lowered at a right angle down, like a goatee; the ears, on the other hand, are more similar in shape to the ears of an animal than a man. As we have already said, this zoomorphism is also manifested in the small plasticity of sao - terracotta heads depicting fantastic creatures reminiscent of the chimeras of medieval cathedrals. Taking into account the wide variety of sao terracotta and the presence of the most developed stylistic forms among them, it can be assumed that the primitivism of some groups of sao terracotta is the result of the conservation of ancient forms of cult sculpture.

It is known that long before the appearance of Europeans in Tropical Africa in various parts of Western Sudan, the Gulf of Guinea and the Congo in different time there were more or less extensive state formations. Unfortunately, we have only fragmentary information about their artistic culture. Only by separate scattered monuments can one judge the art of the states of Ashanti and Baule, the Congo and Krinjabo, Mali and Ghana. We have a more complete picture of the court art of Dahomey in the 18th-19th centuries. But only the art of Ife, which was mentioned above, and especially of Benin, provides extensive material for the analysis and understanding of such a special phenomenon as the art of the early class African states.

The court art of Benin and Ife illuminates a certain phase in the development of art in Tropical Africa, helps to clarify some general patterns of artistic evolution under centralized secular or religious power.

Art of Benin