Lesson "art of the late renaissance". Venice renaissance art

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Hosted at http://www.allbest.ru

Venetian school

The Venetian school, one of the main schools of painting in Italy, with its center in the city of Venice (sometimes also in the small towns of Terraferma - areas of the mainland adjacent to Venice). The Venetian school is characterized by the predominance of the pictorial principle, special attention to the problems of color, the desire to embody the sensual fullness and colorfulness of life. Closely related to countries Western Europe and the East, Venice drew from a foreign culture everything that could serve as its decoration: the elegance and golden sheen of Byzantine mosaics, the stone surroundings of Moorish buildings, the fantasticness of Gothic temples. At the same time, its own original style in art was developed here, gravitating towards ceremonial colorfulness. The Venetian school is characterized by a secular, life-affirming beginning, a poetic perception of the world, man and nature, subtle colorism. The Venetian school reached its greatest prosperity in the era of the Early and High Renaissance, in the work of Antonello da Messina, who opened up for his contemporaries the expressive possibilities of oil painting, the creators of ideally harmonic images of Giovanni Bellini and Giorgione, the greatest colorist Titian, who embodied in his canvases the cheerfulness and colorfulness inherent in Venetian painting. plethora. In the works of the masters of the Venetian school of the 2nd half of the 16th century, virtuosity in conveying the multicolored world, love for festive spectacles and a diverse crowd coexist with overt and hidden drama, an alarming sense of the dynamics and infinity of the universe (paintings by Paolo Veronese and Jacopo Tintoretto). In the 17th century, the traditional interest of the Venetian school in the problems of color in the works of Domenico Fetti, Bernardo Strozzi and other artists coexisted with the techniques of Baroque painting, as well as realistic tendencies in the spirit of caravagism. The Venetian painting of the 18th century is characterized by the flourishing of monumental and decorative painting (Giovanni Battista Tiepolo), household genre(Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, Pietro Longhi), documentary-accurate architectural landscape - veduta (Giovanni Antonio Canaletto, Bernardo Belotto) and lyrical, subtly conveying the poetic atmosphere of everyday life in Venice city landscape (Francesco Guardi).

From the workshop of Gianbellino came two great artists of the High Venetian Renaissance: Giorgione and Titian.

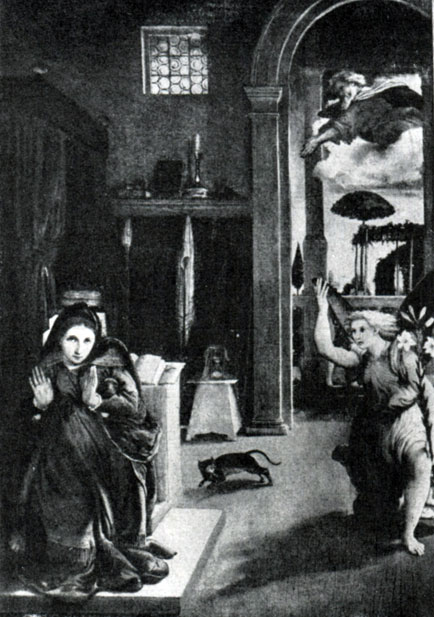

George Barbarelli da Castelfranco, nicknamed Giorgione (1477-1510), is a direct follower of his teacher and a typical artist of the High Renaissance. He was the first on Venetian soil to turn to literary themes, to mythological subjects. Landscape, nature and the beautiful naked human body became for him an object of art and an object of worship. Leonardo is close to Giorgione with a sense of harmony, perfection of proportions, exquisite linear rhythm, soft light painting, spirituality and psychological expressiveness of his images, and at the same time, Giorgione's rationalism, which undoubtedly had a direct influence on him when he was passing from Milan in 1500. in Venice. But Giorgione is more emotional than the great Milanese master, and, like a typical Venice artist, he is interested not so much in linear perspective as in airy and mainly color problems.

Already in the first known work "Madonna of Castelfranco" (circa 1505), Giorgione appears as a fully developed artist; the image of the Madonna is full of poetry, thoughtful dreaminess, permeated with that mood of sadness that is characteristic of all female images of Giorgione. Over the last five years of his life (Giorgione died of the plague, which was a particularly frequent visitor to Venice), the artist created his the best works, executed in oil technique, the main one in the Venetian school at a time when the mosaic became a thing of the past along with the entire medieval artistic system, and the fresco turned out to be unstable in the humid Venetian climate. In the painting of 1506 "Thunderstorm" Giorgione depicts man as part of nature. A woman feeding a child, a young man with a staff (who can be mistaken for a warrior with a halberd) are not united by any action, but are united in this majestic landscape by a common mood, a common state of mind. Giorgione owns the finest and extraordinarily rich palette. The muted tones of the young man's orange-red clothes, his greenish-white shirt, echoing the woman's white cloak, are, as it were, enveloped in that semi-twilight air that is characteristic of pre-storm lighting. The green color has a lot of shades: olive in the trees, almost black in the depths of the water, lead in the clouds. And all this is united by one luminous tone, conveying the impression of unsteadiness, anxiety, anxiety, but also joy, like the very state of a person in anticipation of an impending thunderstorm.

The same feeling of surprise in front of the complex spiritual world of a person is also evoked by the image of Judith, which combines seemingly incompatible features: courageous majesty and subtle poetry. The picture is written in yellow and red ocher, in a single golden color. The soft black-and-white modeling of the face and hands is somewhat reminiscent of Leonard's "sfumato". The pose of Judith, standing by the balustrade, is absolutely calm, her face is serene and thoughtful: a beautiful woman against the backdrop of beautiful nature. But in her hand a double-edged sword glistens coldly, and her tender foot rests on the dead head of Holofernes. This contrast brings a sense of confusion and deliberately breaks the integrity of the idyllic picture.

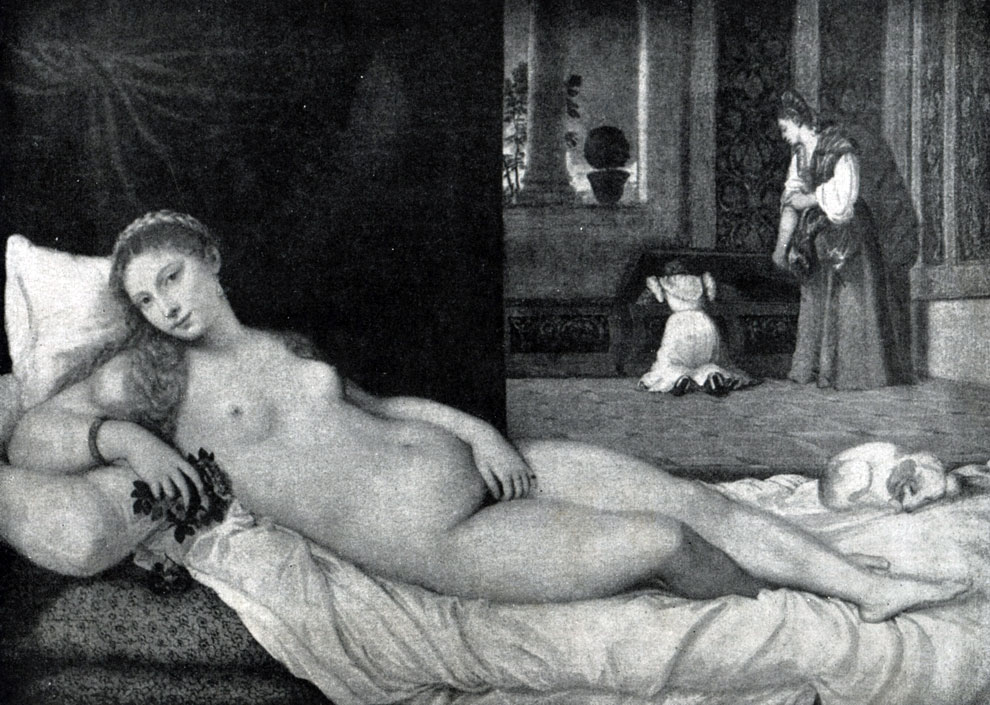

Spirituality and poetry permeate the image of the "Sleeping Venus" (circa 1508-1510). Her body is written easily, freely, gracefully, and it is not without reason that researchers speak of the "musicality" of Giorgione's rhythms; it is not devoid of sensual charm. But the face with closed eyes is chaste and strict, in comparison with it, the Titian Venuses seem to be true pagan goddesses. Giorgione did not have time to complete work on "Sleeping Venus"; according to contemporaries, the landscape background in the picture was painted by Titian, as in another late work of the master - "Country Concert" (1508--1510). This picture, depicting two gentlemen in magnificent clothes and two naked women, one of whom takes water from a well, and the other plays the flute, is the most cheerful and full-blooded work of Giorgione. But this living, natural feeling of the joy of being is not associated with any specific action, full of enchanting contemplation and dreamy mood. The combination of these features is so characteristic of Giorgione that it is precisely the "Country Concert" that can be considered his most typical work. Sensual joy in Giorgione is always poeticized, spiritualized.

Titian Vecellio (1477?--1576) - the greatest artist Venetian Renaissance. He created works on both mythological and Christian subjects, worked in the portrait genre, his coloristic talent is exceptional, compositional inventiveness is inexhaustible, and his happy longevity allowed him to leave behind a rich creative heritage that had a huge impact on posterity. Titian was born in Cadore, a small town at the foot of the Alps, in a military family, studied, like Giorgione, with Gianbellino, and his first work (1508) was joint painting with Giorgione of the barns of the German Compound in Venice. After the death of Giorgione, in 1511, Titian painted in Padua several rooms of scuolo, philanthropic brotherhoods, in which the influence of Giotto, who once worked in Padua, and Masaccio is undoubtedly felt. Life in Padua introduced the artist, of course, to the works of Mantegna and Donatello. Glory to Titian comes early. Already in 1516, he became the first painter of the republic, from the 20s - the most famous artist of Venice, and success does not leave him until the end of his days. Around 1520, the Duke of Ferrara commissioned him a series of paintings in which Titian appears as a singer of antiquity who managed to feel and, most importantly, embody the spirit of paganism ("Bacchanal", "Feast of Venus", "Bacchus and Ariadne").

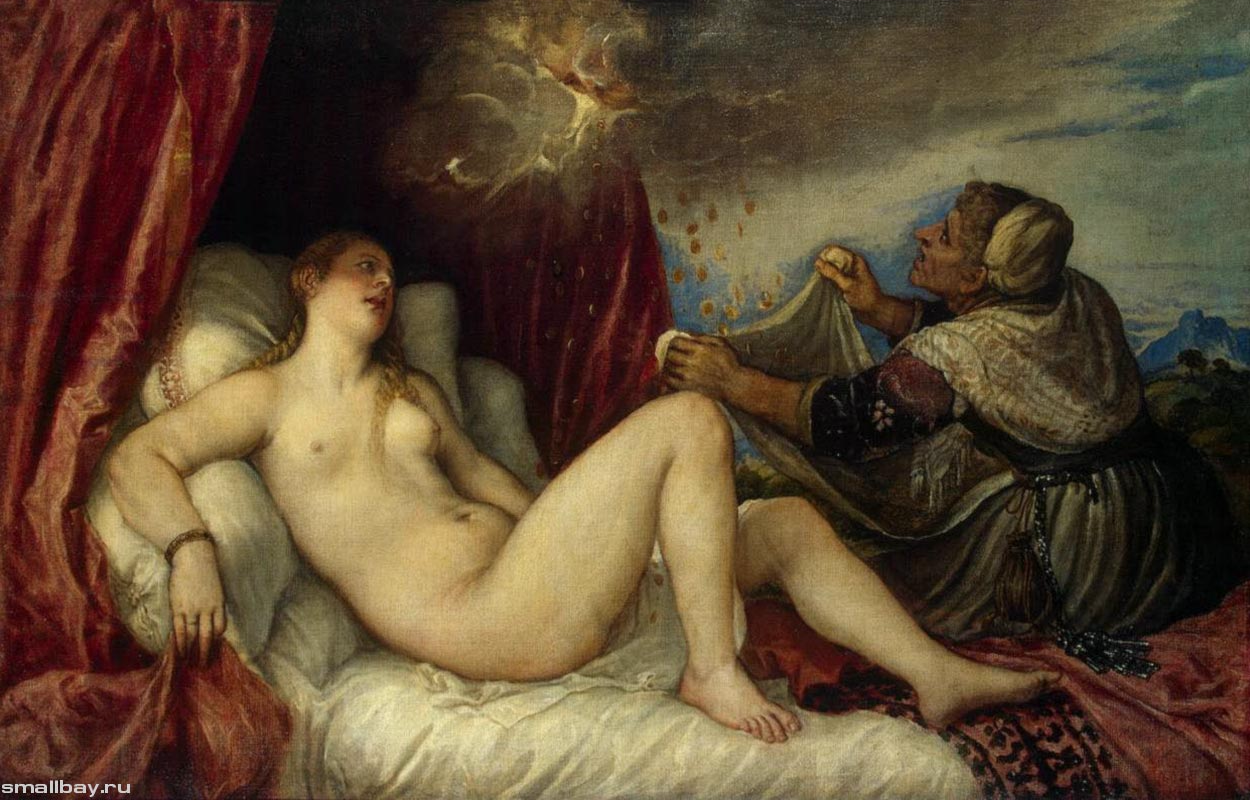

Venice of these years is one of the centers of advanced culture and science. Titian becomes the brightest figure in the artistic life of Venice, together with the architect Jacopo Sansovino and the writer Pietro Aretino, he forms a kind of triumvirate that leads the entire intellectual life of the republic. Wealthy Venetian patricians order altarpieces from Titian, and he creates huge icons: the Ascension of Mary, the Pesaro Madonna (named after the customers depicted in the foreground) and much more - a certain type of monumental composition on a religious plot, which simultaneously plays the role of not only an altar image, but also a decorative panel. In Madonna Pesaro, Titian developed the principle of decentralizing composition, which was unknown to the Florentine and Roman schools. Having shifted the figure of the Madonna to the right, he thus contrasted two centers: the semantic one, personified by the figure of the Madonna, and the spatial one, determined by the vanishing point, placed far to the left, even beyond the frame, which created the emotional intensity of the work. The sonorous pictorial range: Mary's white veil, green carpet, blue, carmine, golden clothes of the upcoming ones - does not contradict, but acts in harmonious unity with the bright characters of the models. Brought up on the "smart" painting of Carpaccio, on the exquisite coloring of Gianbellino, Titian in this period loves plots where you can show the Venetian street, the splendor of its architecture, the festive curious crowd. This is how one of his largest compositions, "The Introduction of Mary into the Temple" (circa 1538), is created - the next step after the "Madonna of Pesaro" in the art of depicting a group scene, in which Titian skillfully combines life's naturalness with majestic elation. Titian writes a lot on mythological subjects, especially after a trip to Rome in 1545, where the spirit of antiquity was comprehended by him, it seems, with the greatest completeness. It was then that his versions of Danae appear (an early version is 1545; all the rest are around 1554), in which, strictly following the plot of the myth, he depicts the princess, languishing awaiting the arrival of Zeus, and the maid, greedily catching the golden rain. Danae is beautiful in accordance with the ancient ideal of beauty, which the Venetian master follows. In all these variants, the Titian interpretation of the image carries a carnal, earthly beginning, an expression of the simple joy of being. His "Venus" (circa 1538), in which many researchers see a portrait of the Duchess Eleonora of Urbino, is close in composition to Dzhordzhonevskaya. But the introduction of a domestic scene in the interior instead of a landscape background, the attentive look of the model's wide-open eyes, the dog in her legs are details that convey the feeling of real life on earth, and not on Olympus.

Throughout his life, Titian was engaged in portraiture. In his models (especially in portraits of the early and middle periods of creativity), the nobility of appearance, the majesty of bearing, the restraint of posture and gesture, created by an equally noble color scheme, and stingy, strictly selected details (portrait of a young man with a glove, portraits of Ippolito Riminaldi , Pietro Aretino, daughter of Lavinia).

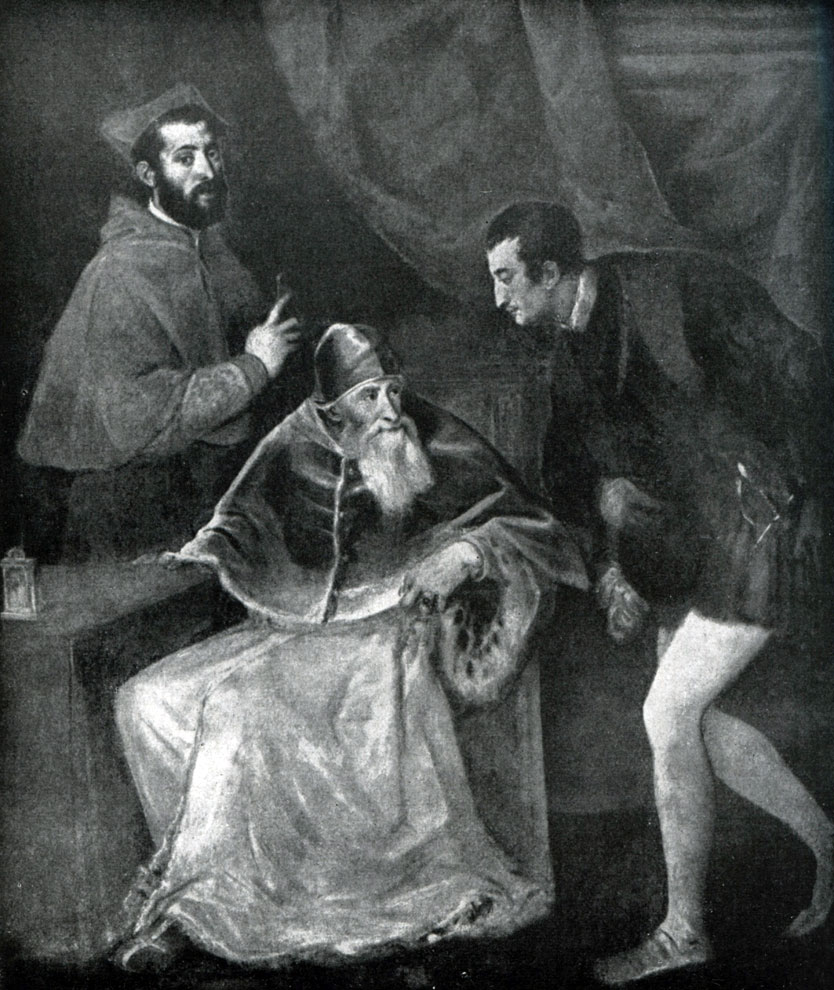

If the portraits of Titian are always distinguished by the complexity of the characters and the intensity of the internal state, then in the years of creative maturity he creates especially dramatic images, contradictory characters, presented in confrontation and clash, depicted with truly Shakespearean force (a group portrait of Pope Paul III with his nephews Ottavio and Alexander Farnese, 1545--1546). Such a complex group portrait developed only in the 17th century Baroque, just as an equestrian ceremonial portrait like Titian's "Charles V at the Battle of Mühlberg" served as the basis for the traditional representative composition of Van Dyck's portraits.

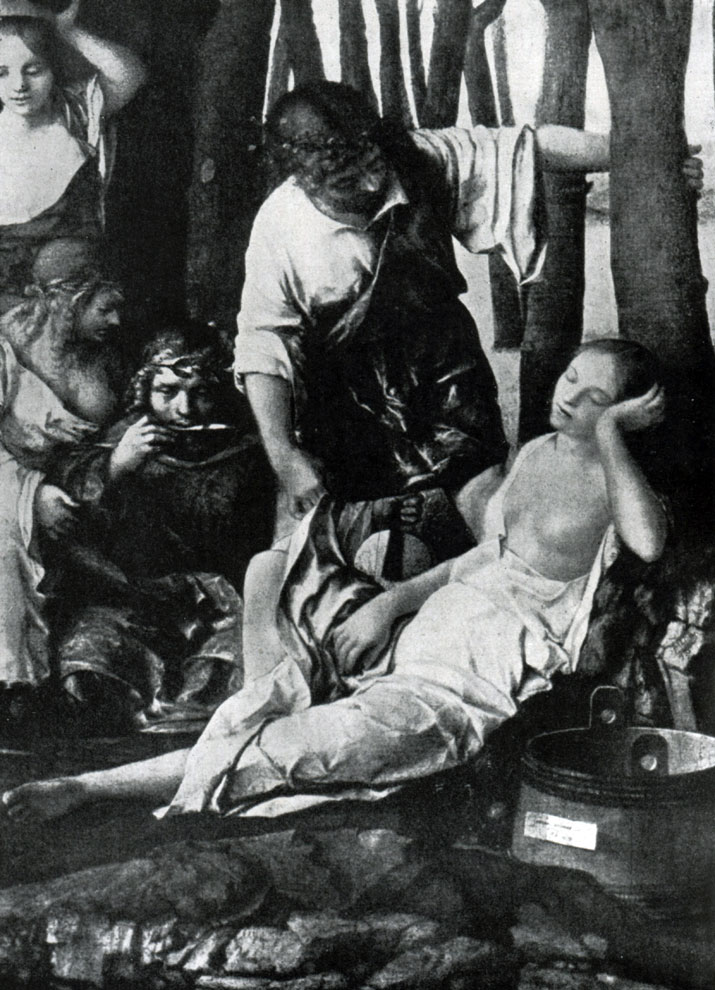

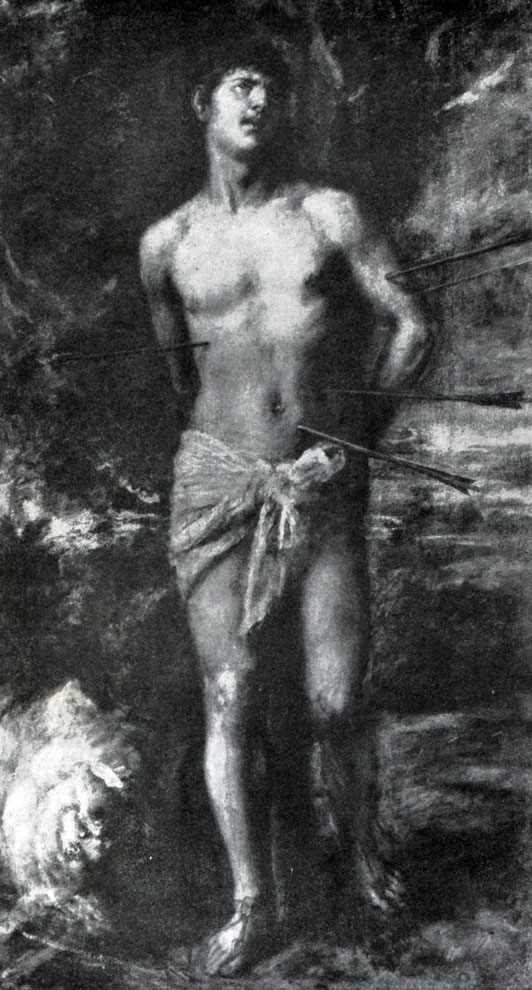

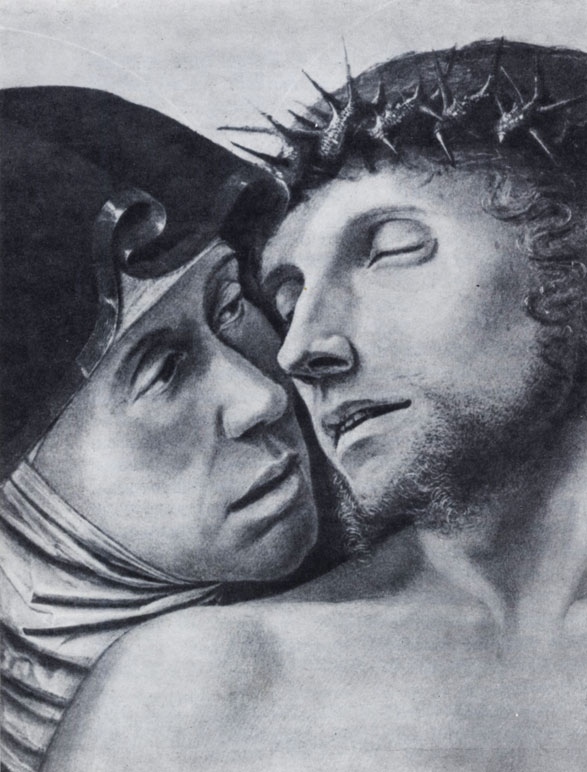

Towards the end of Titian's life, his work undergoes significant changes. He still writes a lot on ancient subjects ("Venus and Adonis", "The Shepherd and the Nymph", "Diana and Actaeon", "Jupiter and Antiope"), but more and more often he turns to Christian themes, to scenes of martyrdom, in which pagan cheerfulness, antique harmony is replaced by a tragic worldview ("Flagellation of Christ", "Penitent Mary Magdalene", "St. Sebastian", "Lamentation"),

The writing technique is also changing: golden light coloring and light glazing give way to powerful, stormy, pasty painting. The transfer of the texture of the objective world, its materiality is achieved by wide strokes of a limited palette. "St. Sebastian" is written, in fact, only ocher and soot. The brushstroke conveys not only the texture of the material, but with its movement the form itself is molded, the plasticity of the depicted is created.

The immeasurable depth of sorrow and the majestic beauty of the human being are conveyed in Titian's last work, Lamentation, completed after the death of the artist by his student. The Madonna, holding her son on her knees, froze in grief, Magdalena throws up her hand in despair, the old man remains in deep mournful thought. The flickering bluish-gray light unites the contrasting color spots of the heroes' clothes, the golden hair of Mary Magdalene, the almost sculpturally modeled statues in the niches and at the same time creates the impression of a fading, passing day, the onset of twilight, enhancing the tragic mood.

Titian died at an advanced age, having lived for almost a century, and is buried in the Venetian church dei Frari, decorated with his altarpieces. He had many students, but none of them was equal to the teacher. The enormous influence of Titian affected the painting of the next century, it was experienced to a large extent by Rubens and Velasquez.

Venice throughout the 16th century remained the last stronghold of the independence and freedom of the country; as already mentioned, it remained faithful to the traditions of the Renaissance for the longest time. But at the end of the century, the features of the impending new era in art, the new artistic direction. This can be seen in the work of two major artists of the second half of this century - Paolo Veronese and Jacopo Tintoretto.

Paolo Cagliari, nicknamed Veronese (he was from Verona, 1528-1588), was destined to become the last singer of the festive, jubilant Venice of the 16th century. He began by making paintings for the Verona palazzos and images for the Verona churches, but fame came to him when, in 1553, he began to work on murals for the Doge's Palace in Venice. From now on, Veronese's life is forever connected with Venice. He makes paintings, but more often he paints large oil paintings on canvas for the Venetian patricians, altarpieces for Venetian churches on their own order or on the official order of the republic. He wins the competition to decorate the library of St. Mark. Glory accompanies him all his life. But no matter what Veronese wrote: "Marriage in Cana of Galilee" for the refectory of the monastery of San George Maggiore (1562--1563; size 6.6 x 9.9 m, depicting 138 figures); paintings whether on allegorical, mythological, secular subjects; whether portraits, genre paintings, landscapes; "The Feast at Simon the Pharisee" (1570) or "The Feast at the House of Levi" (1573), later rewritten at the insistence of the Inquisition, are all huge decorative pictures of the festive Venice, where the Venetian crowd dressed in elegant costumes is depicted against the backdrop of a widely painted perspective of the Venetian architectural landscape, as if the world for the artist was a constant brilliant extravaganza, one endless theatrical action. Behind all this is such a wonderful knowledge of nature, everything is executed in such an exquisite single (silver-pearl and blue) color with all the brightness and variegation of rich clothes, so inspired by the talent and temperament of the artist that the theatrical action acquires a life of credibility. There is a healthy sense of joy in life in Veronese. His powerful architectural backgrounds are not inferior to Raphael's in their harmony, but complex movement, unexpected angles of figures, increased dynamics and congestion in the composition - features that appear at the end of creativity, a passion for image illusionism speak of the advent of art of other possibilities and other expressiveness.

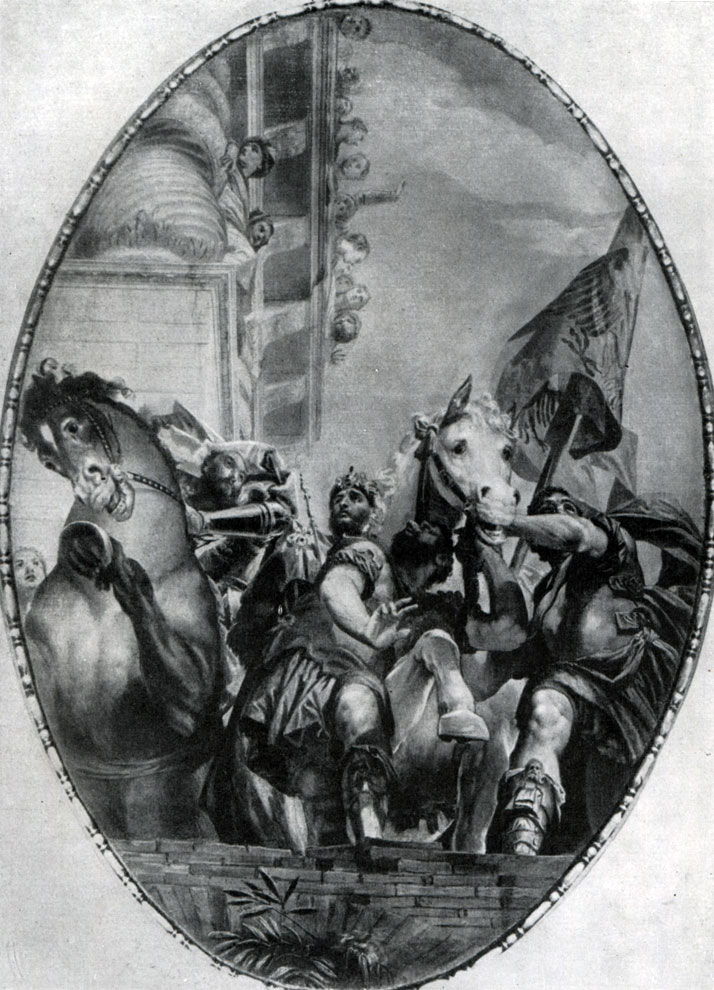

The tragic attitude manifested itself in the work of another artist - Jacopo Robusti, known in art as Tintoretto (1518--1594) ("tintoretto" is a dyer: the artist's father was a silk dyer). Tintoretto spent a very short time in Titian's workshop, however, according to contemporaries, the motto hung on the doors of his workshop: "Michelangelo's drawing, Titian's coloring." But Tintoretgo was perhaps a better colorist than his teacher, although, unlike Titian and Veronese, his recognition was never complete. Numerous works of Tintoretto, written mainly on the subjects of mystical miracles, are full of anxiety, anxiety, and confusion. Already in the first painting that brought him fame, The Miracle of St. Mark (1548), he presents the figure of the saint in such a complex perspective, and all people in a state of such pathos and such stormy movement, which would have been impossible in the art of the High Renaissance in its classical period. Like Veronese, Tintoretto writes a lot for the Doge's Palace, Venetian churches, but most of all for philanthropic brotherhoods. Two of his largest cycles are performed for Scuolo di San Rocco and Scuolo di San Marco.

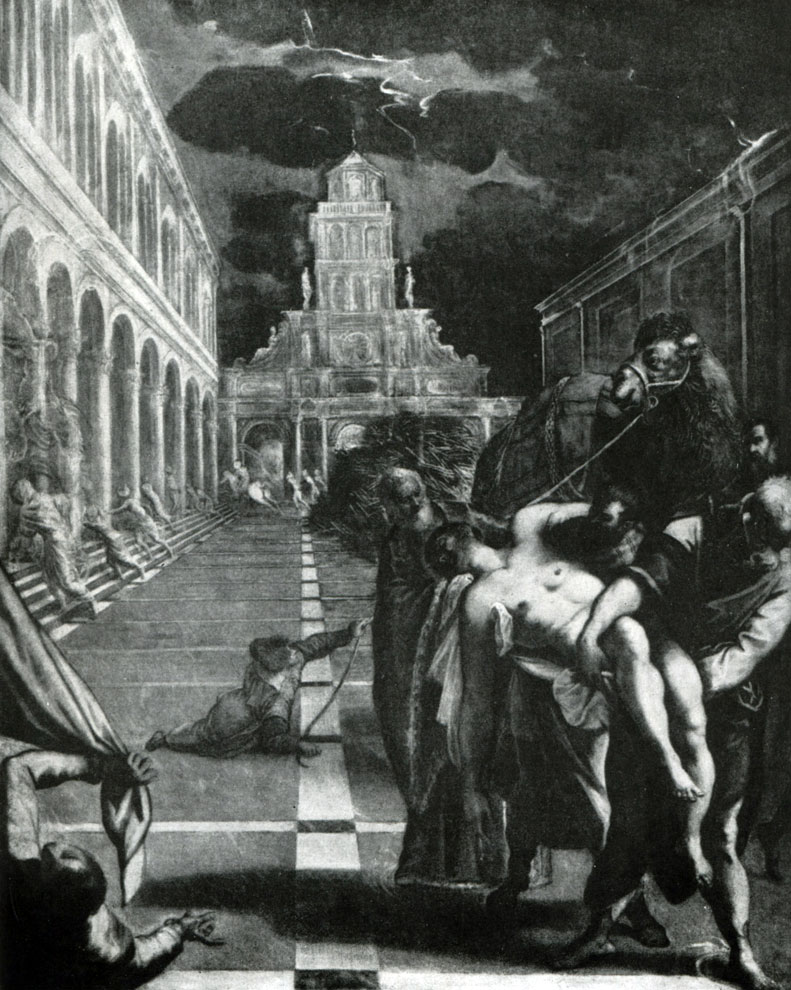

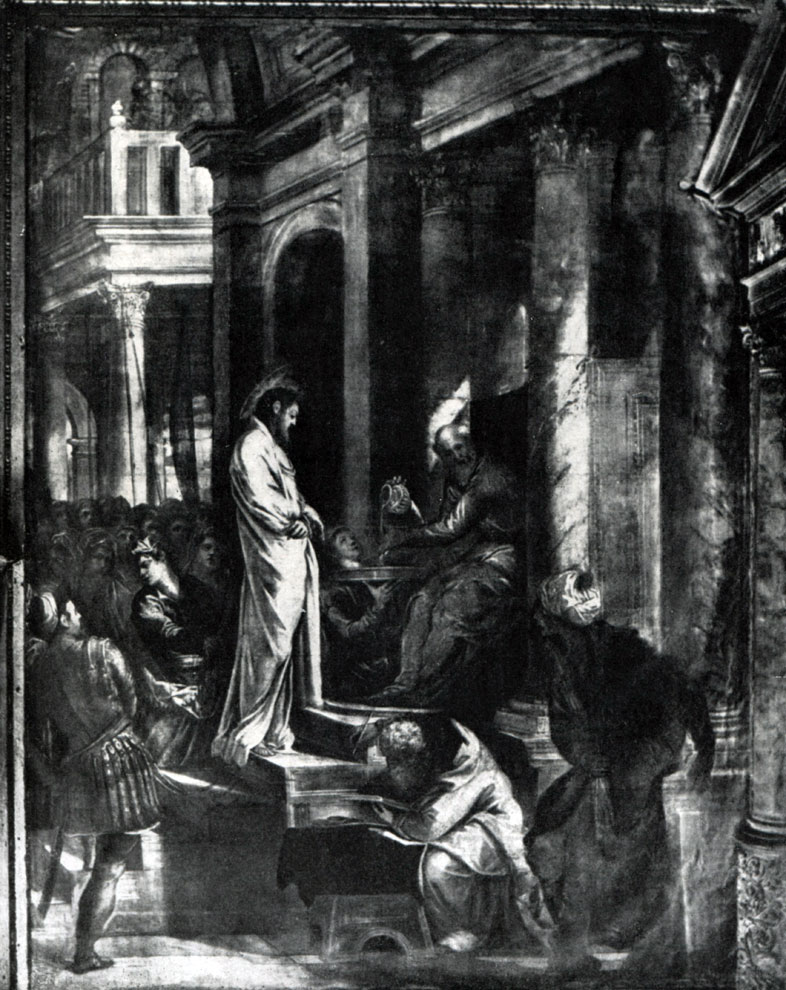

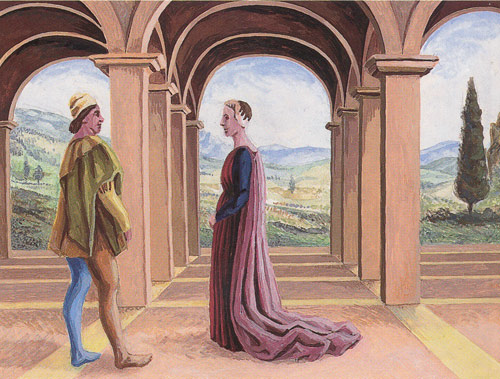

The principle of Tintoretto's figurativeness is built, as it were, on contradictions, which probably frightened off his contemporaries: his images are clearly of a democratic warehouse, the action takes place in the simplest setting, but the plots are mystical, full of exalted feelings, express the ecstatic fantasy of the master, executed with manneristic sophistication . He also has subtly romantic images, fanned by a lyrical feeling (The Salvation of Arsinoe, 1555), but here, too, the mood of anxiety is conveyed by a wavering unsteady light, cold greenish-grayish flashes of color. Unusual is his composition "Introduction to the Temple" (1555), which is a violation of all accepted classical norms of construction. The fragile figure of little Mary is placed on the steps of a steeply rising staircase, at the top of which the high priest awaits her. The feeling of the vastness of space, the swiftness of movement, the power of a single feeling gives special significance to the depicted. Terrible elements, flashes of lightning usually accompany the action in the paintings of Tintoretto, enhancing the drama of the event ("The Abduction of the Body of St. Mark").

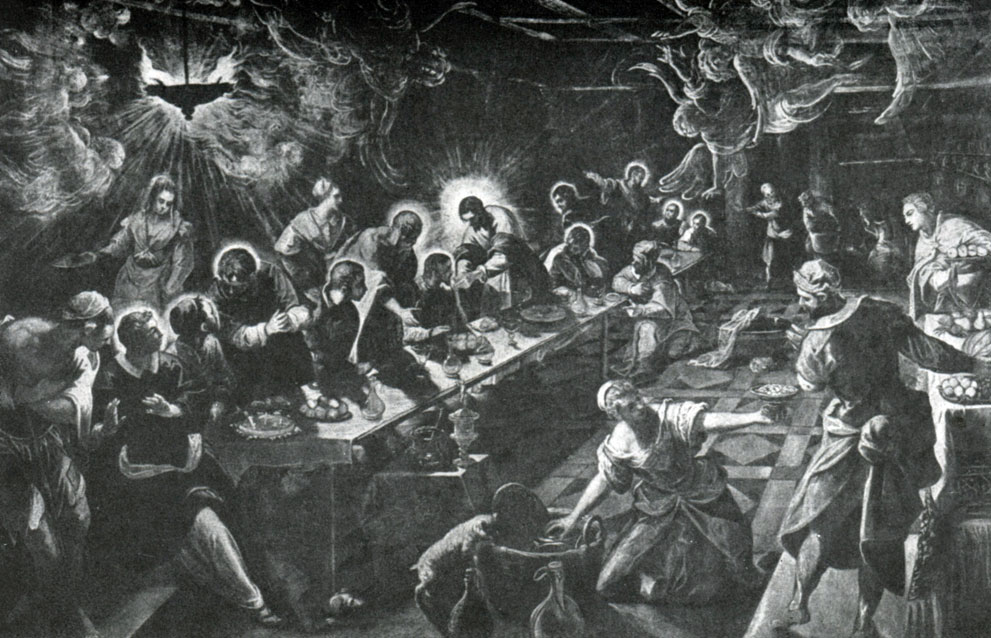

Since the 60s, Tintoretto's compositions have become simpler. He no longer uses contrasts of color spots, but builds a color solution on an unusually diverse transition of strokes, either flashing or fading, which enhances the drama and psychological depth of what is happening. So he wrote "The Last Supper" for the brotherhood of St. Mark (1562--1566).

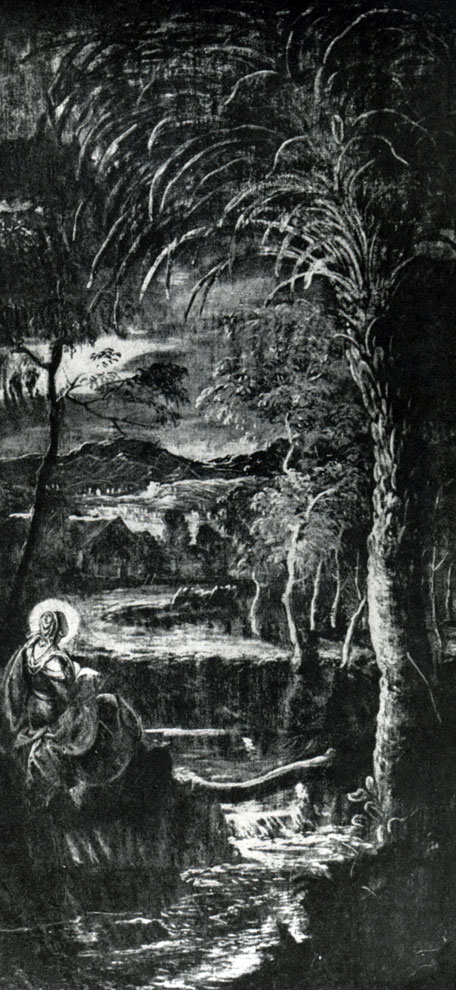

From 1565 to 1587 Tintoretto worked on the decoration of the Scuolo di San Rocco. The giant cycle of these paintings (several dozen canvases and several plafonds), occupying two floors of the room, is imbued with piercing emotionality, a deep human feeling, sometimes a caustic feeling of loneliness, a person’s absorption in boundless space, a feeling of insignificance of a person in front of the greatness of nature. All these sentiments were deeply alien to the humanistic art of the High Renaissance. In one of the last versions of The Last Supper, Tintoretto already presents an almost established system means of expression baroque. A table placed diagonally, flickering light refracted in dishes and grabbing figures from the darkness, sharp chiaroscuro, a plurality of figures presented in complex foreshortenings - all this creates the impression of some kind of vibrating environment, a feeling of extreme tension. Something ghostly, surreal is felt in his later landscapes for the same Scuolo di San Rocco ("Flight into Egypt", "St. Mary of Egypt"). In the last period of creativity, Tintoretto works for the Doge's Palace (composition "Paradise", after 1588).

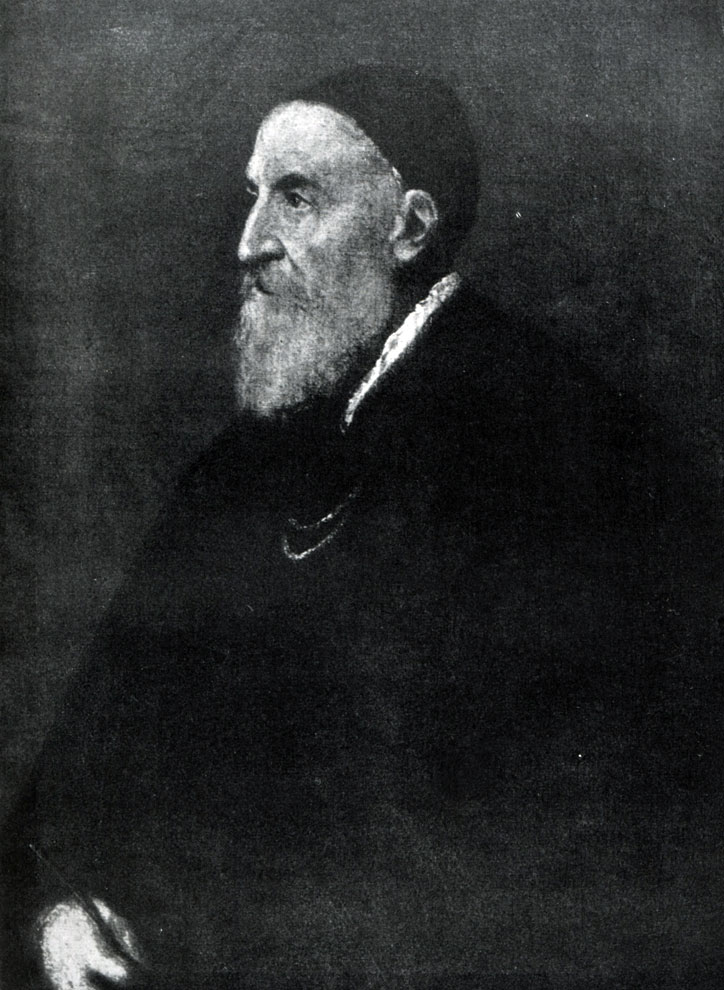

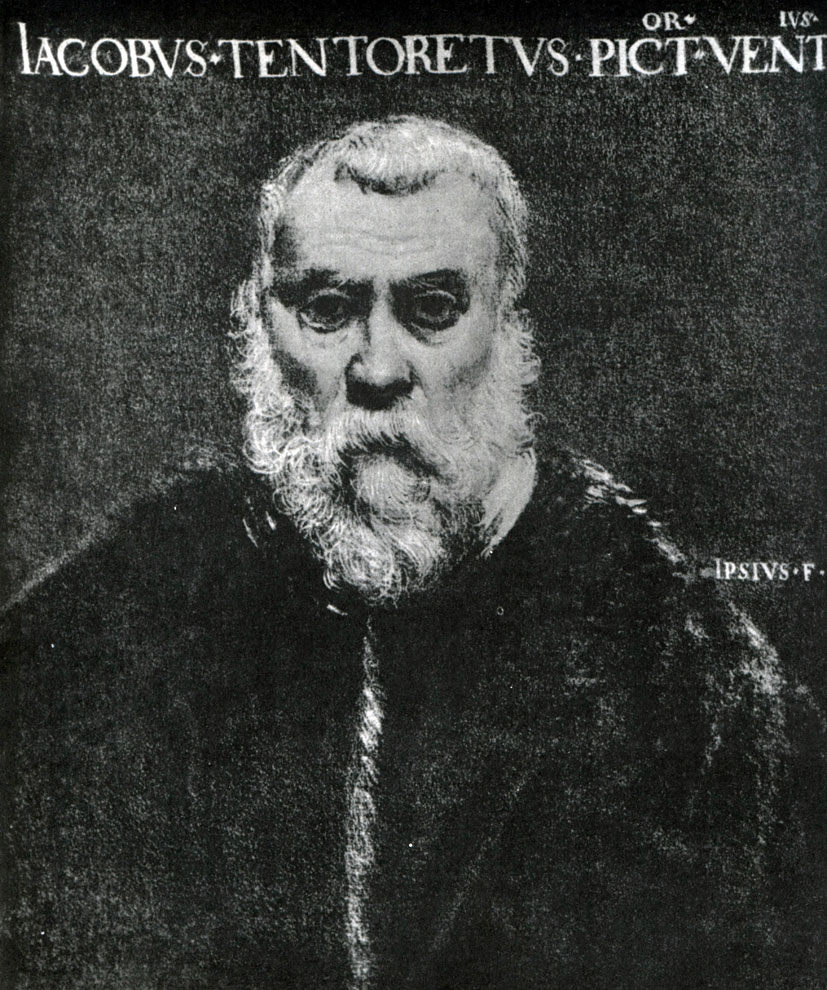

Tintoretto did a lot of portraiture. He portrayed the Venetian patricians, closed in their grandeur, proud Venetian doges. His painting style is noble, restrained and majestic, as is the interpretation of models. Full of heavy thoughts, painful anxiety, mental confusion, the master depicts himself in a self-portrait. But this is a character to which moral suffering has given strength and greatness.

Concluding the review of the Venetian Renaissance, it is impossible not to mention the greatest architect, who was born and worked in Vicenza near Venice and left there excellent examples of his knowledge and rethinking of ancient architecture - Andrea Palladio (1508--1580, Villa Cornaro in Piombino, Villa Rotunda in Vicenza, completed already after his death by students according to his project, many buildings in Vicenza). The result of his study of antiquity was the book "Roman Antiquities" (1554), "Four Books on Architecture" (1570-1581), but antiquity was for him a "living organism", according to the researcher's fair observation. "The laws of architecture live in his soul as instinctively as the instinctive law of verse lives in Pushkin's soul. Like Pushkin, he is his own norm" (P. Muratov).

In subsequent centuries, the influence of Palladio was enormous, even giving rise to the name "Palladianism". The "Palladian Renaissance" in England began with Inigo Jones, continued throughout the 17th century, and only br. Adams began to move away from him; in France, his features are carried by the work of Blondels St. and Ml.; in Russia, "Palladians" were (already in the 18th century) N. Lvov, br. Neyolov, C. Cameron and most of all -J. Quarenghi. In the Russian estate architecture of the 19th century and even in the modern era, the rationality and completeness of the Palladio style manifested itself in the architectural images of neoclassicism.

During the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, Venice was a powerful trading state. Since the 12th century, the arts have flourished here; on the tiny island of Murano, art glassmaking has progressed to such an extent that it is the envy of the rulers of other countries. Glassmaking is very well organized and regulated by the Guild of Glassblowers. Success is ensured by strict quality control, the introduction of new technologies and the protection of trade secrets; in addition, thanks to the well-developed merchant fleet of the Venetian Republic, excellent conditions have developed on the market.

Significant technological progress is observed in the production of colorless, exceptionally pure glass. Due to its resemblance to rock crystal, it was called spaiano. It was first made around 1450, and the authorship is attributed to Angelo Barovier. Crustallo has become synonymous with the term "Venetian glass", which was understood as a combination of the highest purity and transparency with plasticity.

The secrets of blowing technology and new forms are passed from hand to hand. Molds are usually made from other materials, most commonly metal or ceramic. Gothic lines, common as far back as the 16th century, are gradually being replaced by classical, streamlined, more characteristic of the Renaissance.

As for the decor technique, the Venetian masters use everything: both novelties, and the Romanesque and Byzantine techniques that have come into fashion again, and the technique of the Middle East.

The most common among the Venetians was the "hot" technique, in which the decoration is part of the process of making a glass product and is completed in an annealing furnace, when the master gives the object its final shape. The glassblowers of Venice used the dipping method to create the ribbed pattern.

To obtain an elegant, plastic pattern, the product is additionally processed: individual parts are superimposed on hot glass, which allows you to "dress" it in an intricate ornament.

Venetian decorative technique

Venice specializes in glass decoration, which is its integral part. Calcedonio glass is similar to marble, which is achieved by a complex process of mixing glass of different colors and processing accordingly. Invented around 1460, it resembles the semi-precious stone agate or chalcedony, from which its name comes.

To obtain millefiori (thousand colors) glass, a bubble of hot colorless glass from a glass tube is rolled over a smooth board on which pieces of colored glass are randomly scattered. They adhere to the surface of the bladder and are rolled into the surface until it is smooth, after which the bladder is inflated and shaped into the desired shape. The result is the effect of bright patterned inclusions in clear colorless glass. The technique of making "thousand flowers" and chalcedony glass is considered complex. The hot technique for filigree glass is more widely used: thin frosted strips are attached to colorless glass; the resulting glass may have a simple striped pattern (fili) or, in a more complicated version, a pattern with swirling stripes (ritorti). The result is achieved by combining with figured forms.

In cold methods, the decor is applied to the finished glass. Engraving with a diamond needle involves drawing a pattern on glass surfaces with a sharp piece of diamond. It can be an ornament with arabesques or grotesques, made with a contour and shaded with parallel lines. Cold reverse drawing is done on plates and dishes; the pattern turns out to be a detail-nvsh, but it is almost not protected from scratches and chips.

The surface of the products is covered with enamel, made from pigments based on glass mass. The pattern is applied to the surface as long as the glass and enamels remain soft and fusible by lightly heating the object to be decorated and placing it back in the oven. Rough enamel paste allows only a simple design, and was suitable for simple designs. Sometimes a gold leaf was glued to the surface and fired together with enamel.

Venetian style

As the prestige of Venetian glass grows, so does the number of orders; dukes from other countries seek to open their own production of this luxurious glass. Venetian glassmakers do their best to keep the technology secret, but their craftsmen are poached abroad. By the end of the 16th century, Murano glassblowers had lit their kilns in several countries north of the Alps. They try to produce glass in the Venetian style, the same as they did in their homeland, and it is often difficult to distinguish their products from Murano.

The workshops of Solbad Hall, Tyrol, Austria, are among the first to adopt the Venetian blowing style. Some products are attributed to them only because they bear the corresponding coat of arms. Tyrolean workshops specialize in cold painting, although the form of their products remains purely Venetian.

In the northern part of Europe, Antwerp became one of the main producers of Venetian glass. Many glassblowers came from Venice. Nevertheless, local styles also developed, especially in the 17th century.

From Antwerp, the Venetian masters scattered to other countries. The Italian Giacomo Vercellini (1522-1606) moved to London. He is credited with some amazingly elegant glassware of the 1580s. The engraving was done in London by the Frenchman Anthony de Lisle. The masters of a rival glassblower from Altare, northeast Italy, begin to work in the Venetian style in France. They create completely different, usually angular models and more figurative enamel ornamentation.

In Spain, local traditions are strong, the influence of the Venetians was insignificant. Glass is usually honey-colored. When enamel fell out of fashion in the first quarter of the 16th century even among the glassblowers of Venice, the Spaniards still continued to use and improve this technique, incorporating a motif of bright green leaves and stylized animal figures into the ornament.

forest glass

In the vast forests of Central and Northern Europe, since the late Middle Ages, a different style has developed in glassblowing. The forests provided fuel for the glassblowers, and they moved to new places, clearing them of vegetation. Most of all, local raw materials are used: beech and fern ash. because of high level the content of iron oxides used in production, the glass turns out to be an unusual greenish color. It is known as waldglas (forest glass).

Forest glassblowing workshops produce mainly the same type of glassware for wine and beer. Most of the products are in the form of a cone-shaped or barrel-shaped glass, sometimes with a rim at the bottom, most often made using metal clips. The dishes are decorated with "lollipops", or drops, creating a regular pattern. "Lollipops" have both decorative and practical sense- it is convenient to take them with oily fingers.

A common type of drinking ware from the 15th and 16th centuries was the so-called Maigelen (barrel-shaped goblets with a honeycomb motif or faceted).

In the 16th century, models are introduced that originate from barrel-shaped glasses with "lollipops". Krautstrunk (stump) is a thick-walled glass, decorated with elongated "lollipops" as if elongated with tweezers. Another variety is made - Berkemeyer, glasses with a short stem and a relatively cylindrical, two-piece body, which bends inwards at the top.

Reomer, one of the most popular 17th century drinking utensils, originated from Berkemeyer. The top of the Reomer is spherical or egg-shaped; around 1620, they began to be made with a high mouth or stem, which were decorated with "candy" stuck on in a hot way. Reomer is usually used for white wines: the greenish glass goes well with the color of the wine.

Hosted on Allbest.ru

Similar Documents

Prerequisites for the emergence and general characteristics of the Venice Charter. general characteristics applied new modern restoration technologies. Reflection of the provisions of the Venice Charter in the Russian restoration science of the second half of the 20th century.

thesis, added 12/29/2016

Brief information about the life path and creative activity of Giorgione - an Italian artist, a representative of the Venetian school of painting, one of the greatest masters High Renaissance. Brief analysis the most outstanding works of the great artist.

abstract, added 04/26/2013

The concept of the Venetian school of painting. Early Madonnas, landscapes, portraits, altarpieces and mythological compositions. Bellini's life path and legacy. The influence and significance of Andrea Mantegna for the work of Giovanni, the relationship of the two artists.

abstract, added 04/26/2013

Giorgione is an Italian artist, a representative of the Venetian school of painting, one of the greatest masters of the High Renaissance. Subtle poetry, deep lyrical feeling, hidden experiences in the paintings of the master. Intimate-lyrical portraits of Giorgione.

abstract, added 05/13/2013

The study of the Arzamas school of painting - A.V. Stupin and his students. The Stupino school was the only hotbed of artistic knowledge for serf talents, mostly forgotten by history. The history of the school, its features and reasons for the liquidation.

abstract, added 04/20/2008

Study of representatives of the Italian school of painting. Characterization of the features of the main types of fine arts: easel and applied graphics, sculpture, architecture and photography. Study of techniques and methods of working with oil paints.

term paper, added 02/15/2012

The study of the art of the Renaissance, including the development of architecture, the founder of which was Filippo Brunelleschi. Features of the Tuscan, Lombard and Venetian schools, in the style of which the Renaissance trends were combined with local traditions.

abstract, added 01/05/2011

The main approaches to the conceptualization of the concept of "scientific school", its main criteria, classification features. Stages of formation and development of the scientific school "Annals". The creative path of the main representatives of the "Annals" school and their contribution to its development.

thesis, added 06/14/2017

Features of Venetian painting in the Renaissance. Creativity El Greco, the most famous of his paintings. Masterpieces of Spanish artists Diego Velasquez and Francisco Goya. French representatives of impressionism Auguste Renoir and Edouard Manet.

presentation, added 10/01/2012

Analysis of the situation in the field of color and color systems. The study of the features of color theories. Study of the meaning of color in painting. The concept of color harmony. Dependence of chiaroscuro and color. The main stages of creating color in the picture.

On the opposition of the two characters, Titian builds the composition "Caesar's Denarius" (1515-1520, Dresden, Picture gallery): the nobility and sublime beauty of Christ are emphasized by the predatory expression and ugliness of the money-grubbing Pharisee. A number of altar images, portraits and mythological compositions belong to the period of Titian's creative maturity. Titian's fame spread far beyond the borders of Venice, and the number of orders constantly increased. In his works of 1518-1530, grandiose scope and pathos are combined with the dynamics of the construction of the composition, solemn grandeur, with the transfer of the fullness of being, the richness and beauty of rich color harmonies. Such is the “Ascension of Mary” (“Assunta”, 1518, Venice, the church of Santa Maria dei Frari), where the powerful breath of life is felt in the very atmosphere, in the running clouds, in the crowd of apostles, looking with admiration and surprise at the figure of Mary ascending into the sky , strictly majestic, pathetic. The chiaroscuro modeling of each figure is energetic, complex and wide movements, filled with a passionate impulse, are natural. Deep red and blue tones are solemnly sonorous. In The Madonna of the Pesaro Family (1519-1526, Venice, Santa Maria dei Frari), abandoning the traditional centric construction of the altar image, Titian gives an asymmetrical but balanced composition shifted to the right, full of bright vitality. Sharp portrait characteristics endowed with Maria's upcoming customers - the Pesaro family.

In the years 1530-1540, the pathos and dynamics of Titian's early compositions are replaced by vitally direct images, clear balance, and slow narrative. In paintings on religious and mythological themes, the artist introduces a specific environment, folk types, accurately observed details of life. In the scene "Entrance into the Temple" (1534-1538, Venice, Academy Gallery), little Mary is depicted climbing the wide stairs to the high priests. And right there, among the noisy crowd of townspeople who have gathered in front of the temple, the figure of an old woman merchant stands out, seated on the steps next to her goods - a basket of eggs. In the painting "Venus of Urbino" (circa 1538, Florence, Uffizi), the image of a sensual naked beauty is reduced from poetic heights by the introduction in the background of the figures of maids, taking something out of a chest. The color scheme, while maintaining sonority, becomes restrained and deep.

Throughout his life, Titian turned to the portrait genre, acting as an innovator in this area. He deepens the characteristics of the portrayed, noticing the originality of posture, movements, facial expressions, gestures, manners of wearing a suit. His portraits sometimes develop into paintings that reveal psychological conflicts and relationships between people. Already in the early portrait of the “Young Man with a Glove” (1515-1520, Paris, Louvre), the image acquires individual concreteness, and at the same time, it expresses the typical features of a Renaissance man, with his determination, energy, sense of independence, the young man seems to ask a question and waits response. Compressed lips, sparkling eyes, the contrast of white and black in clothes sharpen the characterization. Great drama and complexity of the inner world, psychological and social generalizations are distinguished by portraits of later times, when the theme of a person's conflict with the outside world is born in Titian's work. The portrait of Ippolito Riminaldi (late 1540s, Florence, Pitti Gallery) is striking in revealing the refined spiritual world, whose pale face imperiously attracts with the complexity of the characterization, quivering spirituality. Inner life is concentrated in a glance, at the same time intense and scattered, in it the bitterness of doubts and disappointments.

As a kind of document of the era, a group portrait in the growth of Pope Paul III with his nephews, cardinals Alessandro and Ottavio Farnese (1545-1546, Naples, Capodimonte Museum), is perceived as a kind of document of the era, exposing selfishness and hypocrisy, cruelty and greed, authoritativeness and servility, decrepitude and tenacity - all that that connects these people. The heroic equestrian portrait of Charles V (1548, Madrid, Prado) in knightly armor, against the backdrop of a landscape illuminated by the golden reflections of the setting sun, is vividly realistic. This portrait had a tremendous impact on the composition of the Baroque portrait of the 17th and 18th centuries.

In the 1540s-1550s, the features of picturesqueness sharply increase in Titian's work, he achieves complete unity of plastic light and shade and color solutions. Powerful strokes of light make the colors shine and shimmer. In life itself, he finds the ideal of full-blooded mature beauty embodied in mythological images - "Venus in front of a mirror" (circa 1555, Washington, National Gallery of Art), "Danae" (circa 1554, Madrid, Prado).

The strengthening of the feudal-Catholic reaction and the deep crisis experienced by the Venetian Republic cause an aggravation of the tragic beginning in the late works of the artist. They are dominated by plots of martyrdom and suffering, irreconcilable discord with life, stoic courage; "The Torment of Saint Lawrence" (1550-1555, Venice, Jesuit Church), "Penitent Magdalene" (1560s, St. Petersburg, Hermitage), "Coronation with Thorns" (circa 1570, Munich, Pinakothek), "Saint Sebastian "(about 1570, St. Petersburg, Hermitage)," Pieta "(1573-1576, Venice, Academy Gallery). The image of a person in them still has a powerful force, but loses the features of internal harmonic balance. The composition is simplified, based on a combination of one or more figures with an architectural or landscape background, immersed in twilight; evening or night scenes are illuminated by ominous lightning, the light of torches. The world is perceived in variability and movement. In these paintings, the artist's late pictorial manner was fully manifested, acquiring a freer and broader character and laying the foundations for tonal painting of the 17th century. Refusing bright, jubilant colors, he turns to cloudy, steely, olive complex shades, subordinating everything to a common golden tone. He achieves an amazing unity of the colorful surface of the canvas, using various textural techniques, varying the finest glazes and thick pasty open strokes of paint, sculpting form, dissolving a linear pattern in a light-air medium, giving the form the thrill of life. And in his later, even the most tragic-sounding works, Titian did not lose faith in the humanistic ideal. Man for him until the end remained the highest value of the existing. Full of consciousness of his own dignity, faith in the triumph of reason, wise life experience appears before us in the "Self-Portrait" (circa 1560, Madrid, Prado), an artist who carried the bright ideals of humanism through his whole life.

Y. Kolpinsky

Venetian Renaissance art is an integral and inseparable part of Italian art in general. Close relationship with other foci artistic culture Renaissance in Italy, common historical and cultural destinies - all this makes Venetian art one of the manifestations of Renaissance art in Italy, just as it is impossible to imagine the High Renaissance in Italy in all its diversity of creative manifestations without the work of Giorgione and Titian. The art of the late Renaissance in Italy cannot be understood at all without studying the art of the late Titian, the work of Veronese and Tintoretto.

However, the originality of the contribution of the Venetian school to the art of the Italian Renaissance is not only somewhat different from that of any other school in Italy. The art of Venice represents a special version of the development of the principles of the Renaissance in relation to all art schools in Italy.

The art of the Renaissance took shape in Venice later than in most other centers, in particular than in Florence. The formation of the principles of the artistic culture of the Renaissance in the fine arts in Venice began only in the 15th century. This was determined by no means by the economic backwardness of Venice. On the contrary, Venice, along with Florence, Pisa, Genoa, Milan, was one of the most economically developed centers of Italy. Paradoxical as it may seem, it was precisely the early transformation of Venice into a great commercial, and, moreover, predominantly commercial, rather than a manufacturing power, which began in the 12th century. and especially accelerated in the course of the crusades, is to blame for this delay.

The culture of Venice, this window of Italy and Central Europe, "cut through" to the eastern countries, was closely connected with the magnificent grandeur and solemn luxury of the imperial Byzantine culture and partly with the subtly decorative culture of the Arab world. Already in the 12th century, that is, in the era of the dominance of the Romanesque style in Europe, a wealthy trading republic, creating art that affirmed its wealth and power, widely turned to the experience of Byzantium - the richest, most developed Christian medieval power at that time. In essence, the artistic culture of Venice as early as the 14th century. It was a kind of interweaving of magnificently festive forms of monumental Byzantine art, enlivened by the influence of the colorful ornamentation of the East and peculiarly elegant, decoratively rethought elements of mature Gothic art. In fact, proto-Renaissance tendencies made themselves felt under these conditions very weakly and sporadically.

Only in the 15th century there is an inevitable and natural process of the transition of Venetian art to the secular positions of the artistic culture of the Renaissance. Its originality was manifested mainly in the desire for increased festivity of color and composition, in greater interest in the landscape background, in human environment landscape environment.

In the second half of the 15th century there is a formation of the Renaissance school in Venice as a significant and original phenomenon, which occupied an important place in the art of the Italian Quattrocento.

Venice in the middle of the 15th century reaches the highest level of his power and wealth. The colonial possessions and trading posts of the "Queen of the Adriatic" covered not only the entire eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea, but also spread widely throughout the eastern Mediterranean. In Cyprus, Rhodes, Crete, the banner of the Lion of St. Mark flutters. Many of the noble patrician families that make up the ruling elite of the Venetian oligarchy act overseas as rulers of large cities or entire regions. The Venetian fleet firmly controls almost the entire transit trade between East and Western Europe.

However, the defeat of the Byzantine Empire by the Turks, which ended with the capture of Constantinople, shook the trading positions of Venice. Yet in no way can one speak of the decline of Venice in the second half of the 15th century. The general collapse of the Venetian eastern trade came much later. The Venetian merchants, who at that time had been partially released from trade, invested huge amounts of money in the development of crafts and manufactories in Venice, and partly in the development of rational agriculture in their possessions located on the peninsula adjacent to the lagoon (the so-called terra farm). Moreover, the rich and still full of vitality republic in 1509-1516 managed to defend its independence in the fight against the hostile coalition of a number of European powers, combining the force of arms with flexible diplomacy. The general upsurge, due to the successful outcome of the difficult struggle that temporarily rallied all sections of Venetian society, caused the growth of the features of heroic optimism and monumental festivity that are so characteristic of the art of the High Renaissance in Venice, starting with Titian. The fact that Venice retained its independence and, to a large extent, its wealth, determined the duration of the heyday of the art of the High Renaissance in the Venetian Republic. The turn to the late Renaissance was outlined in Venice only around 1540.

The period of formation of the High Renaissance falls, as in the rest of Italy, at the end of the 15th century. It was during these years that the narrative art of Gentile Bellini and Carpaccio began to resist the art of Giovanni Bellini, one of the most remarkable masters of the Italian Renaissance, whose work marks the transition from the early to the High Renaissance.

Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430-1516) not only develops and improves the achievements accumulated by his immediate predecessors, but also raises Venetian art to a higher level. In his paintings, the connection between the mood created by the landscape and the state of mind of the heroes of the composition is born, which is one of the remarkable achievements of modern painting in general. At the same time, in the art of Giovanni Bellini, and this is the most important thing, the significance of the moral world of man is revealed with extraordinary force. True, the drawing in his early works is sometimes somewhat harsh, the combinations of colors are almost sharp. But the feeling of the inner significance of a person's spiritual state, the revelation of the beauty of his inner experiences, reach in the work of this master already in this period of enormous impressive power.

Giovanni Bellini frees himself early from the narrative verbosity of his immediate predecessors and contemporaries. The plot in his compositions rarely receives a detailed dramatic development, but all the more through the emotional sound of color, through the rhythmic expressiveness of the drawing and, finally, through the restrained, but full of inner strength mimicry, the greatness of the spiritual world of man is revealed.

The early works of Giovanni Bellini can be brought closer to the art of Mantegna (for example, The Crucifixion; Venice, Correr Museum). However, already in the altarpiece in Pesaro, the clear linear “Mantenevian” perspective is enriched by a more subtly conveyed aerial perspective than that of the Padua master. The main difference between the young Venetian and his older friend and relative (Mantegna was married to Bellini's sister) is expressed not so much in the individual features of the letter, but in the more lyrical and poetic spirit of his work as a whole.

Particularly instructive in this regard is his so-called "Madonna with a Greek inscription" (1470s; Milan, Brera). This image of a mournfully pensive Mary, vaguely reminiscent of an icon, gently hugging a sad baby, speaks of another tradition from which the master repels - the tradition of medieval painting. However, the abstract spirituality of the linear rhythms and color chords of the icon is decisively overcome here. Restrainedly strict in their expressiveness, the color ratios are concrete. The colors are true, the solid modeling of the volumes of the modeled form is very real. The subtly clear sadness of the rhythms of the silhouette is inextricably linked with the restrained vital expressiveness of the movements of the figures themselves, with the lively human expression of Mary's face. Not abstract spiritualism, but a poetically inspired, deep human feeling is expressed in this simple and modest-looking composition.

In the future, Bellini, deepening and enriching the spiritual expressiveness of his artistic language, simultaneously overcomes the features of rigidity and harshness of the early manner. Since the end of the 1470s. he, relying on the experience of Antonello da Messina (who worked in Venice from the mid-1470s), introduces colored shadows into his compositions, saturating them with light and air (“Madonna with Saints”, 1476), giving the whole composition a wide rhythmic breath.

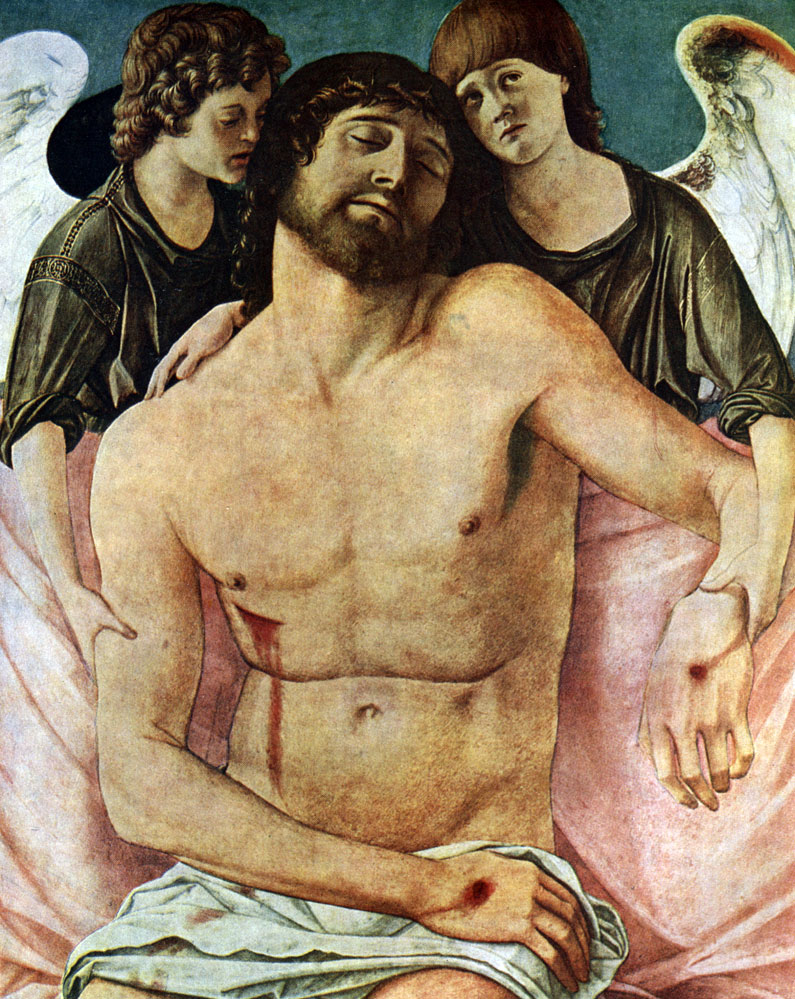

In the 1580s Bellini enters the time of his creative maturity. His "Lamentation of Christ" (Milan, Brera) is striking in its combination of almost merciless truthfulness of life (the mortal cold blue of Christ's body, his half-pendulous jaw, traces of torture) with the genuine tragic grandeur of the images of mourning heroes. The general cold tone of the gloomy radiance of the colors of the robes of Mary and John is fanned by the evening grayish-blue light. The tragic despair of the look of Mary, who clung to her son, and the mournful anger of John, not reconciled with the death of a teacher, rhythms that are severely clear in their straightforward expressiveness, the sadness of a desert sunset, so consonant with the general emotional structure of the picture, are composed into a kind of mournful requiem. It is no coincidence that at the bottom of the board on which the picture is written, an unknown contemporary inscribed the following words in Latin: “If the contemplation of these mourning eyes will tear your tears, then the creation of Giovanni Bellini is capable of crying.”

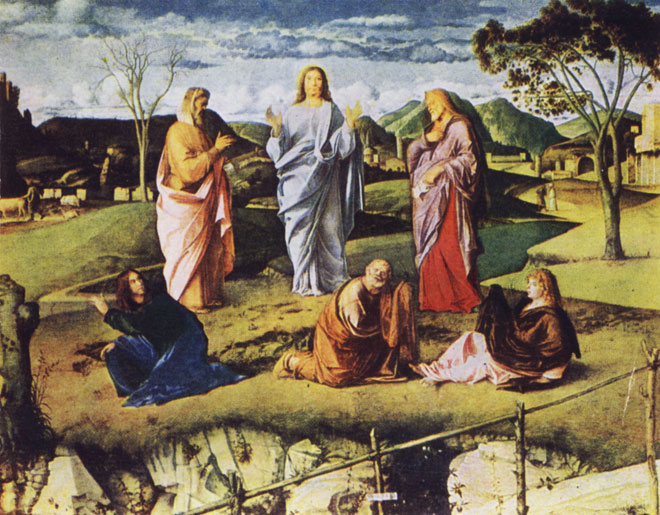

During the 1580s Giovanni Bellini takes a decisive step forward, and the master becomes one of the founders of the art of the High Renaissance. The originality of the art of the mature Giovanni Bellini comes out clearly when comparing his "Transfiguration" (1580s; Naples) with his early "Transfiguration" (Museum Correr). In the "Transfiguration" of the Correr Museum, the rigidly traced figures of Christ and the prophets are located on a small rock, reminiscent of both a large pedestal and an iconic "bream". Somewhat angular in their movements (in which the unity of vital characteristic and poetic elation of gesture has not yet been achieved) the figures are stereoscopic. Light and cold-clear, almost flashy colors of volumetrically modeled figures are surrounded by a cold-transparent atmosphere. The figures themselves, despite the bold use of colored shadows, are still distinguished by a certain static and uniform uniformity of illumination.

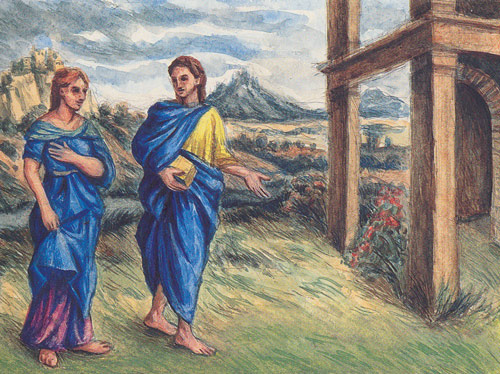

The figures of the Neapolitan "Transfiguration" are located on a gently undulating plateau, characteristic of the northern Italian foothills, whose surface, covered with meadows and small groves, spreads over the rocky-vertical walls of the cliff located in the foreground. The viewer perceives the whole scene as if he were on a path running along the edge of a cliff, fenced with a light railing of hastily tied, unpeeled felled trees. The immediate reality of the perception of the landscape is extraordinary, especially since the entire foreground, and the distance, and the middle plan are bathed in that slightly damp, light-air environment that would be so characteristic of Venetian painting of the 16th century. At the same time, the restrained solemnity of the movements of the majestic figures of Christ, the prophets and prostrate apostles, the free clarity of their rhythmic juxtapositions, the natural dominance of human figures over nature, the calm expanse of landscape distances create that mighty breath, that clear grandeur of the image, which make us foresee in this work the first features of a new stage in the development of the Renaissance.

The calm solemnity of the style of the mature Bellini is embodied in the monumental balance of the composition “Madonna of St. Job” (1580s; Venice Academy). Bellini places Mary, seated on a high throne, against the background of the conch of the apse, which creates a solemn architectural background, consonant with the calm grandeur of human images. The upcoming ones, despite their relative abundance (six saints and three angels praising Mary), do not clutter up the compositions. The figures are harmoniously distributed in easily readable groups, which are clearly dominated by a more solemn and spiritually rich image of Mary with the baby.

Colored shadows, soft shining light, calm sonority of color create a feeling of general mood, subordinate numerous details to the general rhythmic, coloristic and compositional-figurative unity of the whole.

In the "Madonna with Saints" from the Church of San Zaccaria in Venice (1505), written almost simultaneously with the "Madonna of Castelfranco" by Giorgione, the old master created a work remarkable for the classical balance of the composition, the masterful arrangement of the few majestic heroes immersed in deep thought. Perhaps the image of the Madonna herself does not reach the same significance as in the Madonna of St. Job. But the gentle poetry of the youth playing the viol at Mary's feet, the stern gravity and at the same time the softness of the facial expression of the gray-bearded old man immersed in reading, are really beautiful and full of high ethical significance. The restrained depth of the transfer of feelings, the perfect balance between the generalized sublimity and the concrete vitality of the image, the noble harmony of color found their expression in his Berlin Lamentation.

Fig. pp. 248-249

Calmness, clear spirituality are characteristic of all the best works of Bellini's mature period. Such are his numerous Madonnas: for example, “Madonna with Trees” (1490s; Venice Academy) or “Madonna in the Meadows” (c. 1590; London, National Gallery), striking with the plein air luminosity of painting. The landscape not only faithfully conveys the appearance of the nature of the terra farm - wide plains, soft hills, distant blue mountains, but reveals in terms of gentle elegy the poetry of the labors and days of rural life: a shepherd resting by his flocks, a heron descending near a swamp, a woman stopping at the well crane. In this cool spring landscape, so consonant with the quiet tenderness of Mary, reverently Bent over the baby who fell asleep on her knees, that special unity, the inner consonance of the breath of the life of nature and the spiritual life of man, which is so characteristic of the Venetian painting of the High Renaissance, has already been achieved. It is impossible not to notice in passing that in the interpretation of the image of the Madonna herself, which has a somewhat genre character, Bellini's interest in the pictorial experience of the masters is noticeable. Northern Renaissance.

A significant, although not leading place in the work of the late Bellini is occupied by those compositions usually associated with some poetic work or religious legend, which the Venetians were fond of.

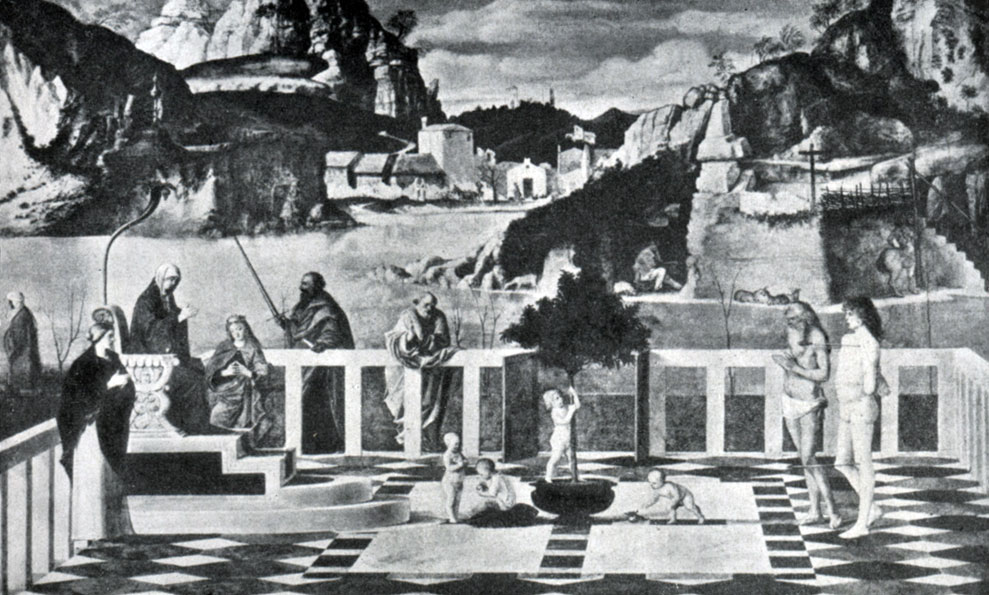

This is inspired by a French poem of the 14th century. the so-called "Lake Madonna" (Uffizi). Against the backdrop of calmly majestic and somewhat severe mountains, rising above the motionless deep grayish-blue waters of the lake, the figures of saints located on the marble open terrace act in silvery soft lighting. In the center of the terrace is an orange tree in a tub, with several naked babies playing around it. To the left of them, leaning against the marble of the balustrade, stands the venerable old man, the apostle Peter, deeply thoughtful. Next to him, raising his sword, stands a black-bearded man dressed in a crimson-red mantle, apparently the Apostle Paul. What are they thinking? Why and where are the elder Jerome, dark bronze from sunburn, and the thoughtful naked Sebastian slowly walking? Who is this slender Venetian with ashy hair, wrapped in a black scarf? Why did this solemnly enthroned woman, perhaps Mary, fold her hands in prayer? Everything seems mysteriously obscure, although it is more than likely that the contemporary of the master, a refined connoisseur of poetry and a connoisseur of the language of symbols, the allegorical plot meaning of the composition was clear enough. And yet, the main aesthetic charm of the picture is not in the ingenious symbolic story, not in the elegance of the rebus decoding, but in the poetic transformation of feelings, the subtle spirituality of the whole, the elegantly expressive juxtaposition of motives that vary the same theme - the noble beauty of the human image. If Bellini's Madonna of the Lake to some extent anticipates the intellectual refinement of Giorgione's poetry, then his Feast of the Gods (1514; Washington, National Gallery), which is distinguished by a wonderful cheerful pagan conception of the world, rather anticipates the heroic optimism of "poetry" and mythological compositions. young Titian.

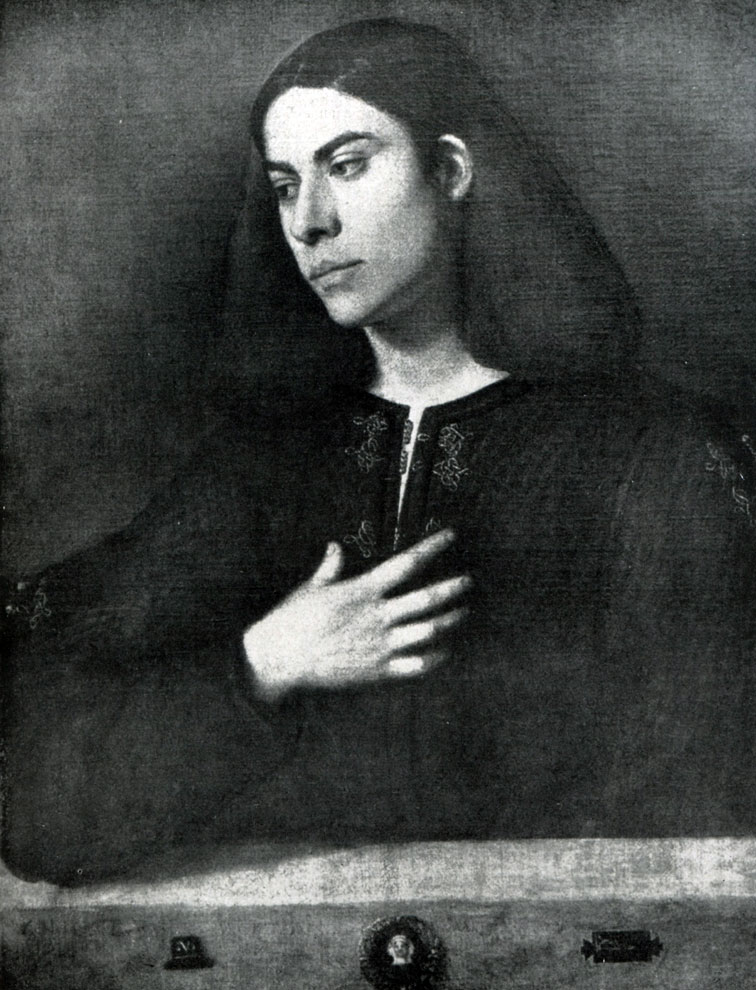

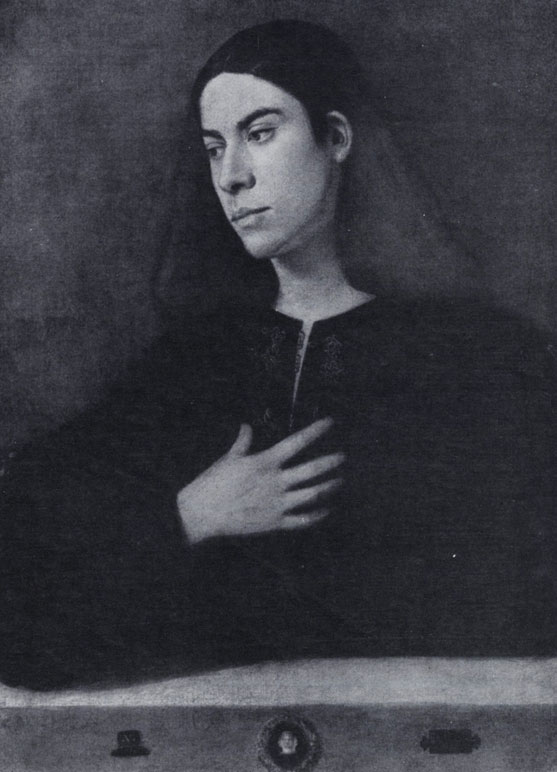

Giovanni Bellini also addressed the portrait. His relatively few portraits, as it were, prepare the flowering of this genre in Venetian painting of the 16th century. Such is his portrait of a boy, an elegant dreamy youth. In this portrait, that image of a beautiful person, full of spiritual nobility and natural poetry, is already being born, which will be fully revealed in the works of Giorgione and the young Titian. "Boy" Bellini - This is the childhood of the young "Brocardo" Giorgione.

Bellini's late work is characterized by a wonderful portrait of the Doge (before 1507), which is distinguished by sonorously shining color, excellent modeling of volumes, accurate and expressive transmission of all the individual originality of the character of this old man, full of courageous energy and intense intellectual life.

In general, the art of Giovanni Bellini - one of the greatest masters of the Italian Renaissance - refutes the once widespread opinion about the supposedly predominantly decorative and purely "painterly" nature of the Venetian school. Indeed, in the further development of the Venetian school, the narrative and outwardly dramatic aspects of the plot will not occupy a leading place for some time. But the problems of the richness of the inner world of a person, the ethical significance of a physically beautiful and spiritually rich human personality, conveyed more emotionally, sensually concretely than in the art of Tuscany, will always occupy an important place in the creative activity of the masters of the Venetian school.

One of the masters of the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, whose work was formed under the decisive influence of Giovanni Bellini, was Giambattista Cima da Conegliano (c. 1459-1517/18). In Venice he worked between 1492-1516. Cima owns large altarpieces in which, following Bellini, he skillfully combined figures with architectural frames, often placing them in an arched opening (“John the Baptist with four saints” in the church of Santa Maria del Orto in Venice, 1490s, “ Unbelief of Thomas"; Venice, Academy, "St. Peter the Martyr", 1504; Milan, Brera). These compositions are distinguished by a free, spacious placement of figures, which allows the artist to widely show the landscape background unfolding behind them. For landscape motifs Cima usually used the landscapes of his native Conegliano, with castles on high hills reached by steep winding roads, with isolated trees and a light blue sky with light clouds. Not reaching the artistic height of Giovanni Bellini, Cima, however, like him, combined in his best works a clear drawing, plastic completeness in the interpretation of figures with rich color, slightly touched by a single golden tone. Cima was also the author of the lyrical images of Madonnas characteristic of the Venetians, and in his remarkable Introduction to the Temple (Dresden, Picture Gallery) he gave an example of a lyric-narrative interpretation of the theme with a subtle outline of individual everyday motifs.

The next stage after the art of Giovanni Bellini was the work of Giorgione, the first master of the Venetian school, wholly owned by the High Renaissance. George Barbarelli of Castelfranco (1477/78-1510), nicknamed Giorgione, was a junior contemporary and student of Giovanni Bellini. Giorgione, like Leonardo da Vinci, reveals the refined harmony of a spiritually rich and physically perfect person. Just like Leonardo, Giorgione's work is distinguished by deep intellectualism and, it would seem, crystalline rationality. But, unlike Leonardo, whose deep lyricism of art is very hidden and, as it were, subordinated to the pathos of rational intellectualism, the lyrical principle, in its clear agreement with the rational principle, in Giorgione makes itself felt with extraordinary force. At the same time, nature, the natural environment in the art of Giorgione begins to play an increasingly important role.

If we still cannot say that Giorgione depicts a single air environment that connects the figures and objects of the landscape into a single plein-air whole, then we, in any case, have the right to assert that the figurative emotional atmosphere in which both the characters and nature live in Giorgione is the atmosphere is already optically common both for the background and for the characters in the picture.

Few works of both Giorgione himself and his circle have survived to our time. A number of attributions are controversial. However, it should be noted that the first complete exhibition of works by Giorgione and the Giorgionescos, held in Venice in 1958, made it possible not only to make a number of clarifications in the circle of the master’s works, but also to attribute to Giorgione a number of previously controversial works, helped to more fully and clearly present the character his work as a whole.

Relatively early works by Giorgione, completed before 1505, include his Adoration of the Shepherds in the Washington Museum and Adoration of the Magi in the National Gallery in London. In The Adoration of the Magi (London), with the well-known fragmentation of the drawing and the insurmountable rigidity of the color, the master’s interest in conveying the inner spiritual world of the characters is already felt.

The initial period of creativity Giorgione completes his wonderful composition "Madonna da Castelfranco" (c. 1505; Castelfranco, Cathedral). In his early works and the first works of the mature period, Giorgione is directly connected with that monumental heroizing line, which, along with the genre-narrative line, passed through all the art of the Quattrocento and on the achievements of which the masters of the generalizing monumental style of the High Renaissance relied in the first place. So, in the "Madonna of Castelfranco" the figures are arranged according to the traditional compositional scheme adopted for this theme by a number of masters of the Northern Italian Renaissance. Mary sits on a high plinth; to the right and left of her, St. Francis and the local saint of the city of Castelfranco Liberale stand before the viewer. Each figure, occupying a certain place in a strictly built and monumental, clearly readable composition, is nevertheless closed in itself. The composition as a whole is somewhat solemnly motionless. II, at the same time, the relaxed arrangement of the figures in a spacious composition, the soft spirituality of their quiet movements, the poetic image of Mary herself create in the picture that atmosphere of a somewhat mysterious pensive dreaminess that is so characteristic of the art of a mature Giorgione, who avoids the embodiment of sharp dramatic collisions.

From 1505, the period of the artist's creative maturity began, soon interrupted by his fatal illness. During this short five years, his main masterpieces were created: "Judith", "Thunderstorm", "Sleeping Venus", "Concert" and most of the few portraits. It is in these works that the mastery of the specific pictorial and figuratively expressive possibilities of oil painting, characteristic of the great masters of the Venetian school, is revealed. Indeed, a characteristic feature of the Venetian school is the predominant development of oil painting and the weak development of fresco painting.

In the transition from the medieval system to the Renaissance realistic painting, the Venetians, of course, almost completely abandoned mosaics, the increased brilliant and decorative color of which could no longer fully meet the new artistic tasks. True, the increased light radiance of the iridescent shimmering mosaic painting, although transformed, indirectly, but influenced the Renaissance painting of Venice, which always gravitated towards sonorous clarity and radiant richness of color. But the mosaic technique itself, with rare exceptions, should have become a thing of the past. The further development of monumental painting had to go either in the form of fresco, wall painting, or on the basis of the development of tempera and oil painting.

The fresco in the humid Venetian climate very early revealed its instability. Thus, the frescoes of the German Compound (1508), executed by Giorgione with the participation of the young Titian, were almost completely destroyed. Only a few half-faded fragments, spoiled by dampness, have survived, among them the figure of a naked woman, full of almost Praxitele charm, made by Giorgione. Therefore, the place of wall painting in proper sense this word was occupied by a wall panel on canvas, designed for a specific room and performed using the technique of oil painting.

Oil painting received a particularly wide and rich development in Venice, not only because it was the most convenient painting technique for replacing frescoes, but also because the desire to convey the image of a person in close connection with his natural environment, interest in the realistic embodiment of tonal and the coloristic richness of the visible world could be revealed with particular fullness and flexibility precisely in the technique of oil painting. In this regard, tempera painting on boards for easel compositions, precious with its large color strength, clearly shining sonority, but more decorative in nature, inevitably had to give way to oil, which more flexibly conveys the light-color and spatial shades of the environment, molding the form more softly and sonorously. human body. For Giorgione, who worked relatively little in the field of large monumental compositions, these possibilities, inherent in oil painting, were especially valuable.

One of the most mysterious in its plot sense of the works of Giorgione of this period is The Thunderstorm (Venice Academy).

It is difficult for us to say on what specific plot "Thunderstorm" is written.

But no matter how vague the external plot meaning for us, which, apparently, neither the master himself, nor the refined connoisseurs and connoisseurs of his art of that time, did not attach decisive importance, we clearly feel the artist’s desire through a kind of contrasting juxtaposition of images to reproduce a certain special state of mind. , with all the versatility and complexity of sensations, characterized by the integrity of the general mood. Perhaps this one of the first works of a mature master is still excessively complicated and outwardly intricate compared to his later works. And yet, all the characteristic features of the mature style of Giorgione in it quite clearly assert themselves.

The figures are already located in the landscape environment itself, although still within the foreground. The diversity of nature's life is shown amazingly subtly: flashing lightning from heavy clouds; the ash-silver walls of buildings in a distant city; a bridge spanning a river; waters, sometimes deep and motionless, sometimes flowing; winding road; sometimes gracefully fragile, sometimes lush trees and bushes, and closer to the foreground - fragments of columns. Into this strange landscape, fantastic in its combinations, and so truthful in details and general mood, a mysterious figure of a naked woman with a scarf thrown over her shoulders, feeding a child, and a young shepherd are inscribed. All these heterogeneous elements form a peculiar, somewhat mysterious whole. The softness of the chords, the muffled sonority of the colors, as if enveloped in the semi-twilight air characteristic of pre-storm lighting, create a certain pictorial unity, within which rich correlations and gradations of tones develop. The orange-red robe of the young man, his shimmering greenish-white shirt, the gentle bluish tone of the woman’s white cape, the bronze oliveness of the greenery of the trees, now dark green in deep pools, now the river water shimmering in the rapids, the heavy lead-blue tone of the clouds - everything is shrouded , united at the same time by a very vital and fabulously mysterious light.

It is difficult for us to explain in words why these so opposite figures are here somehow incomprehensibly united by a sudden echo of distant thunder and a flashing snake of lightning, illuminating with a ghostly light the nature warily hushed in anticipation. "Thunderstorm" deeply poetically conveys the restrained excitement of the human soul, awakened from its dreams by the echoes of distant thunder.

Fig. pp. 256-257

This feeling of the mysterious complexity of the inner spiritual world of a person, hidden behind the apparent clear transparent beauty of his noble external appearance, finds expression in the famous "Judith" (before 1504; Leningrad, the Hermitage). "Judith" is formally a composition on a biblical theme. Moreover, unlike the paintings of many Quattrocentists, it is a composition on a theme, and not its illustration. It is characteristic that the master depicts not some culminating moment from the point of view of the development of the event, as the Quattrocento masters usually did (Judith strikes the drunken Holofernes with a sword or carries his severed head with a maid).

Against the backdrop of a calm pre-sunset clear landscape under the shade of an oak tree, slender Judith stands thoughtfully leaning on the balustrade. The smooth tenderness of her figure is set off in contrast by the massive trunk of a mighty tree. Softly scarlet clothes are permeated with a restlessly broken rhythm of folds, as if by a distant echo of a passing whirlwind. In her hand she holds a large double-edged sword rested with a sharp end on the ground, the cold shine and straightness of which contrastly emphasizes the flexibility of a half-naked leg trampling Holofernes' head. An imperceptible half-smile glides across Judith's face. This composition, it would seem, conveys all the charm of the image of a young woman, coldly beautiful and clear, which is echoed, like a kind of musical accompaniment, by the soft clarity of peaceful nature. At the same time, the cold cutting edge of the sword, the unexpected cruelty of the motif - a tender naked foot trampling on a dead head - brings a feeling of some kind of vague anxiety and anxiety into this seemingly harmonious, almost idyllic in mood picture.

On the whole, of course, the clear and calm purity of the dreamy mood remains the dominant motive. However, the very bliss of the image and the mysterious cruelty of the motive of the sword and the trampled head, the almost rebus complexity of this dual mood leave the modern viewer in some confusion. But Giorgione's contemporaries, apparently, were less struck by the cruelty of the contrast (Renaissance humanism was never overly sensitive), rather than attracted by that subtle transmission of echoes of distant storms and dramatic conflicts, against which the acquisition of refined harmony, the happy state of a dreamily dreaming beautiful human soul.

It is typical for Giorgione that in the image of a person he is interested not so much in the unique strength and brightness of an individually expressed character, but in a certain subtly complex and at the same time harmoniously integral ideal of a perfect person, or, more precisely, the ideal of that spiritual state in which a person resides. Therefore, in his compositions, that portrait specificity of characters is almost absent, which, with some exceptions (for example, Michelangelo), is present in the monumental compositions of most masters of the Italian Renaissance. Moreover, Giorgione's compositions themselves can only be called monumental to a certain extent. As a rule, they are small in size. They are not addressed to large crowds of people. The refined muse of Giorgione - This is the art that most directly expresses the aesthetic and moral world of the humanistic elite of Venetian society. These are paintings designed for long-term calm contemplation by an art connoisseur with a subtle and complexly developed inner spiritual world. This is the specific charm of the master, but also his certain limitations.

In literature, there is often an attempt to reduce the meaning of Giorgione's art to the expression of the ideals of only this small humanistically enlightened patrician elite of Venice of that time. However, this is not entirely true, or rather, not only so. The objective content of Giorgione's art is immeasurably broader and more universal than the narrow social stratum with which his work is directly connected. The feeling of the refined nobility of the human soul, the desire for the ideal perfection of the beautiful image of a person living in harmony with environment, with the outside world, had a great general progressive significance for the development of culture.

As mentioned, interest in portrait sharpness is not characteristic of Giorgione's work. This does not mean at all that his characters, like the images of classical ancient art, are devoid of any concrete originality. This is not true. His magi in the early Adoration of the Magi and the philosophers in The Three Philosophers (c. 1508) differ from each other not only in age, but also in their personal appearance. Nevertheless, philosophers, with all the individual differences in images, are first of all perceived not so much as unique, bright, portrait-characterized individuals, or even more so as an image of three ages (a young man, a mature husband and an old man), but as the embodiment of various sides, various facets of the human spirit.

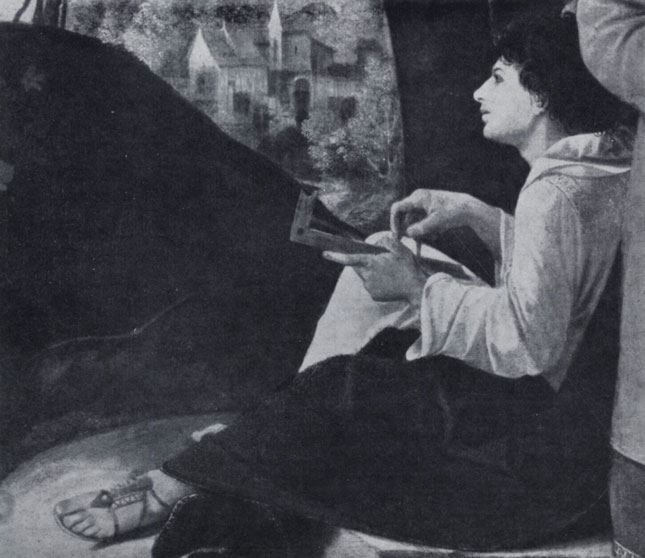

Giorgione's portraits are a kind of synthesis of the ideal and living concrete person. One of the most characteristic is his remarkable portrait by Antonio Brocardo (c. 1508-1510; Budapest, Museum). In it, of course, the individual portrait features of a noble young man are accurately and clearly conveyed, but they are clearly softened, subordinated to the image of a perfect person.

at ease free movement the hands of a young man, the energy felt in a body half-hidden under loose-wide robes, the noble beauty of a pale swarthy face, a head bowed on a strong and slender neck, the beauty of the contour of an elastically defined mouth, the pensive dreaminess of a gaze looking far and away from the viewer - all this creates a complete of noble power, the image of a man engulfed in a deep, clear-calm thought. The soft curve of the bay with still waters, the silent mountainous coast with solemnly calm buildings form a landscape background, which, as always with Giorgione, does not unisonly repeat the rhythm and mood of the main figure, but, as it were, indirectly consonant with this mood.

The softness of the cut-off sculpting of the face and hands is somewhat reminiscent of Leonardo's sfumato. Leonardo and Giorgione simultaneously solved the problem of combining the plastically clear architectonics of the forms of the human body with their softened modeling, which makes it possible to convey the richness of its plastic and chiaroscuro shades - so to speak, the very “breathing” of the human body. If in Leonardo it is rather gradations of light and dark, the finest shading of the form, then in Giorgione sfumato has a special character - it is, as it were, a micro-modeling of the volumes of the human body with that wide stream of soft light that floods the entire space of the paintings. Therefore, Giorgione's sfumato also conveys that interaction of color and light, which is so characteristic of Venetian painting of the 16th century. If his so-called portrait of Laura (c. 1505-1506; Vienna) is somewhat prosaic, then his other female images are, in essence, the embodiment of ideal beauty.

Giorgione's portraits begin a remarkable line of development of the Venetian, in particular Titian, portrait of the High Renaissance. The features of the Giorgione portrait will be further developed by Titian, who, however, unlike Giorgione, has a much sharper and stronger sense of the individual uniqueness of the depicted human character, a more dynamic perception of the world.

Giorgione's work ends with two works - his "Sleeping Venus" (c. 1508-1510; Dresden) and the Louvre "Concert". These paintings remained unfinished, and the landscape background in them was completed by Giorgione's younger friend and student, the great Titian. "Sleeping Venus", in addition, has lost some of its pictorial qualities due to a number of damages and unsuccessful restorations. But be that as it may, it was in this work that the ideal of the unity of the physical and spiritual beauty of man was revealed with great humanistic fullness and almost ancient clarity.

Immersed in a calm slumber, naked Venus is depicted against the backdrop of a rural landscape, the calm gentle rhythm of the hills is in such harmony with her image. The cloudy atmosphere softens all contours and at the same time preserves the plastic expressiveness of forms.

Like other creations of the High Renaissance, George's Venus is closed in its perfect beauty and, as it were, alienated both from the viewer and from the music of the surrounding nature, consonant with its beauty. It is no coincidence that she is immersed in clear dreams of a quiet sleep. The right hand thrown behind the head creates a single rhythmic curve that embraces the body and closes all forms into a single smooth contour.

A serenely light forehead, calmly arched eyebrows, gently lowered eyelids and a beautiful strict mouth create an image of transparent purity indescribable in words. Everything is full of that crystal transparency, which is achievable only when a clear, unclouded spirit lives in a perfect body.