Byzantine architecture. Byzantine style in architecture

Byzantine architecture

Content:

Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………..3

I Chapter. Early Byzantine architecture…………………………………………………….6

1. Origins and origins of Byzantine architecture……………......................6

2. Byzantine urban development………………………………………………….7

a). Byzantine cross-domed temple…………………………………….9

3. The “golden age” of the empire…………………………………………………………..11

4. The greatest of the architectural monuments of Byzantium - St. Sophia Cathedral……………………………………………………………………………...13

Chapter II. Middle Byzantine architecture……………………………………………..20

1. The main features of the Middle Byzantine architecture…………………....20

2. Constantinople architectural school in the middle time………………...21

3. Eastern Byzantine architectural school in the Middle Byzantine period………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Chapter III. Late Byzantine architecture……………………………………………23

Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………...26

List of used literature……………………………………………………….28

Introduction

The history of Byzantium begins in the 4th century, from the time when Emperor Constantine ascended the throne of the Roman Empire (324-337). He moved the capital of the empire to the city of Constantinople. This had a very deplorable effect on the Roman Empire, which as a result split into two parts: Western and Eastern, which later received the name of Byzantium from historians. Shortly before this, in 313, the Edict of Milan allowed the free practice of Christianity, and in 395 it was recognized as the official religion of both parts of the empire. It is hardly possible to find an event that would have a greater impact on the entire subsequent history of ¾ of both Byzantium and Western Europe.

The Middle Ages were the heyday of the feudal system with its typical domination of the landowning class, non-economic measures of coercion, the predominance of subsistence farming, the weak development of commodity production and, as a result, political fragmentation. Equally typical of him were peasant uprisings, the association of urban artisans and merchants in workshops and guilds, the system of vassal hierarchy and the monarchy as the predominant form of government.

Features of the feudal system also affected its architecture. In this era of constant warfare, much attention was paid to the construction of fortresses, and the military architecture of the Middle Ages provided much that was new in comparison with antiquity. At this time, such details appeared as combat parapets with battlements and loopholes, loopholes, simple and hinged, closed defensive balconies, watchtowers, etc. New methods of protecting the fortress gates with the help of additional fortifications were developed and the main types of fortresses were created - a castle located in a mountainous or flat area, a city fortress wall and a fortified monastery.

monasteries, wide use which was also one of the features of the Middle Ages, needed to be fortified both due to the fact that great wealth was often stored within their walls, and because they were built not only in cities, but also far from them, and had to be in war time serve as a refuge for the surrounding population. In addition, monasteries, especially in the early Middle Ages, were important cultural centers. They stored and copied books, chronicles (chronicles), schools were kept. In cases where monasteries arose in sparsely populated areas, they contributed to the spread Agriculture, and the erection of monastic buildings, especially stone churches, contributed to the emergence of new builders and artists.

The emergence of a large number of monasteries became possible due to the enormous importance of religion in people's lives, characteristic of the Middle Ages. Religion strengthened with its authority the existing social and political system, and state life was often almost inseparable from church life.

Under these conditions, the significance that church buildings had in the Middle Ages is understandable. They were not only a place of worship, but also the main type of public buildings. The close connection of religion with state and public life was the reason why the architecture of churches, especially the main cathedrals of large cities, reflected not only religious, but also social ideology.

The Christian religion originated in the era of late antiquity as the religion of the oppressed classes of the Roman state and spread among the broad sections of its population. Christian churches were supposed to accommodate numerous worshipers within their walls and give them the opportunity to see and hear the divine service well enough, which was performed in the eastern part of the temple. On the other hand, the feudal system could not but exert its influence, so the builders of some cathedral and palace churches had to take care to separate representatives of the ruling class from the common people within them. AT individual countries inside the churches, men were also separated from women who were baptized from those preparing to be baptized and penitents, and in monastic churches - monks from the laity.

In accordance with this, the temple consisted of an altar - a place of worship, accessible only to the clergy, a vast main part and a vestibule adjoining it from the west, where in early era there were penitents and those who had not yet received baptism, the catechumens. The main room was divided by pillars necessary for its large size into separate naves - "ships", which in turn helped to divide the worshipers into different categories. The choirs also served the same purpose, often dividing the western and side parts of the main building of the temple into two tiers.

New ideological and artistic tasks arose in the Middle Ages during the construction of temples. This was due to a completely different idea of God than before: the anthropomorphized deities of the ancient world were replaced by the Christian God, invisible and incomprehensible to human feelings. The ideas about the world became different: the imperfect, transient material world surrounding a person was opposed to another world, perfect and eternal, the inhabitant of which can become after his death a person who managed to overcome his sinful sensual nature in earthly life.

Christian churches with all their appearance should have reminded of another world, where the Lord is invisibly present and where the material principle is subordinate to the spiritual. All this was the reason for the strong difference between medieval Christian churches and ancient pagan ones. The difference between them was intensified by the nature of the images that adorned both temples. opposition spirituality the material left its mark on medieval painting and sculpture and on the methods of synthesis of these arts and architecture.

So, in the history of Byzantium, three stages in the development of the Byzantine Empire and Byzantine culture were defined:

Early Byzantine (V-VIII centuries)

Middle Byzantine (VIII-XIII centuries)

Late Byzantine (XIII-XV centuries)

Each of the three periods had its own characteristics, developed from the characteristics of the previous period on the basis of a new stage in the development of Byzantine society and the state.

Thus, this term paper consists of three chapters, each of which is devoted to the development of Byzantine architecture in a different period of the existence of the empire.

Problem term paper: the influence of external factors, in particular, religion on the formation and development of Byzantine architecture.

The purpose of the course work: to consider in detail the features of the development of Byzantine architecture throughout the existence of the empire.

To achieve the goal and solve the problem, literature on the topic under study helps. For example, such books as Goldstein A.F. "Architecture" - about the birth, flourishing and change architectural styles, it reflects the most important and interesting phenomena in the history of architecture. Yakobson A.L. "Patterns of the development of medieval architecture" - this book traces the patterns of development of architecture, depending on the change social conditions, ideology, economic and political environment. Stankova Ya., Pekhar I. "Thousand-year development of architecture" - the book gives an overview of the development of architecture and urban planning. "The Art of Byzantium" V.D. Likhacheva, "Byzantine Culture" Udaltsova, World History of Architecture and many other books provide information in full, which is systematized and clearly presented. The selected material helps to reveal the topic and make the work interesting and well perceived.

I chapter. Early Byzantine architecture

1. Origins and origin of Byzantine architecture.

The question of the origins and origins of Byzantine architecture is still lively debated in scientific literature. There are also disputes about the time of the addition of Byzantine architecture.

During the transition from late antiquity to Byzantium, a wide variety of architectural types existed, which, mutually intersecting, influenced and reborn each other. Such a motley picture is very characteristic of the transition period. Gradually, step by step, in different ways various areas of the late antique world in architecture, individual features began to be outlined and slowly developed, which later entered the system of early Byzantine society. The most significant were the features associated with the emergence and development of the dome and the centric architectural system.

On the eve of the formation of Byzantine architecture, the basilica architectural type was quite widespread. In different areas, he had different options. The basilica plan was most clearly expressed in the buildings of Italy, and especially of Rome itself.

Remaining within the architectural type of the basilica, it should be noted the shortening of the basilicas, which we find in various parts of the then Christian world, and mainly in the East.

A very significant type of temple building of this period was the martyrium, that is, the church over the tomb of a saint. Among the martyrias of various plans, large monumental buildings with a plan in the form of a four-leaf stand out especially. They appeared in the eastern regions of the Late Antique world. Many of them still had wooden domes, but there were also those that were covered with brick domes. The quatrefoil in the plan very much emphasized the central point of the main room, even to the detriment of the altar.

Of all the architectural types that existed on the eve of the emergence of Byzantine architecture, the domed basilica, which was later laid as the basis for Sophia of Constantinople, was of the greatest importance for Byzantine architecture.

With regard to building materials and constructive techniques, the architecture of the period of the formation of Byzantine architecture is divided into two large schools, each of which made its own very significant contribution to its formation. One of these schools is the metropolitan, Constantinople; the other, eastern, is most clearly represented by the buildings of Syria.

The Syrian school is characterized by masonry of beautifully hewn stone blocks. Overlappings - usually wooden. Very often in monumental structures, and perhaps in residential buildings, wooden domes were used, the inner surfaces of which were sometimes decorated with mosaics. Syrian masonry is a further development of ancient, Greek masonry. However, it is possible that in some cases the outer surfaces of the walls were covered with a thin layer of plaster.

In the Constantinopolitan school, building materials and techniques were less uniform and present a complex picture. The main difference from Syria is the very widespread use of bricks and vaults.

Solving the question of the origin of masonry, in which several rows of stone alternate with rows of brick, is very important for clarifying the origins of Byzantine masonry in the capital. It can be argued that around 400 in Asia Minor, the alternation of stone and brick in the masonry of walls was widespread. As examples of its application, one can cite such monuments as buildings of the 4th century BC. in Nicomedia and the church of Mary in Ephesus, as well as outside of Asia Minor the arch of Galerius and the church of George in Thessalonica. In Constantinople, similar masonry is found in the city walls and other early buildings. In the church of Sergius and Bacchus, brick begins to predominate in the masonry for the first time. In its walls, stone linings serve only as an addition to the brickwork. In Sofia, they are used only in the most important places. The predominance of brick is observed in Constantinople already in the masonry of the hippodrome.

With regard to the artistic side of architecture in the period of early Byzantine architecture, two main trends clearly stand out. Syrian and partly Asia Minor architecture leans towards distinct geometric volumes set in isolation, towards small window openings, a small number of them, towards static interiors. In the architecture of Constantinople and in the architecture of other largest cities In the Byzantine world, there is a tendency to complex dynamic interiors, to their predominance over the outer masses of the building, to dissected, even sometimes fragmented volumes and their connection with urban development.

2. Byzantine urban development.

Until the end of the existence of the Byzantine Empire, the traditions of ancient urban planning continued to live in it. This was especially expressed in Constantinople. The trend towards regular planning is noticeable until the late Byzantine period.

Already in the early Byzantine period, centralization appeared in the urban ensemble, reflecting leading start Byzantine state. The streets converge towards the city center, in which the main place is occupied by the cathedral.

Highly great importance for the Byzantine city, they had powerful fortress walls surrounding it, which is due to the historical prerequisites for the life of the Byzantine Empire, which was constantly under the threat of barbarian attacks. The walls of many Byzantine cities, especially Constantinople, were architectural structures that influenced the development of architecture.

Relatively little is known about the residential development of Byzantine cities. It can be argued that free planning of a purely utilitarian nature prevailed in ordinary urban residential buildings. The Byzantine palace system was a development of an ordinary residential building. The most prominent rich houses and palaces had colonnades on the facades facing the main streets, which carried ceilings over the sidewalks.

Byzantine monasteries were a special type of architectural ensemble. The most peculiar were suburban monasteries, usually represented by fortress ensembles. Their main buildings were the residential and outbuildings of the monks, adjoining the fortress walls, and in the center there was a temple and a refectory.

The nature of Byzantine culture was clearly manifested in the predominance of temple buildings in Byzantine architecture. The types of Byzantine churches were very diverse and developed according to individual historical periods. The most outstanding types are: the domed basilica, the peristyle type of the church, the churches covered with a dome on eight pillars and the cross-domed buildings. In all these architectural types, a dome dominated the pulpit, covering the central part of the building, which adjoins the altar in the apse. The central part is surrounded by additional rooms for those present at the service.

Byzantine architects sought to lighten walls and pillars as much as possible. They made large openings and thus connected the interiors with the outer space. Separate parts of the interior have always been organically linked into one compact whole. As for the temple interiors, despite the large openings and good connection with the outer space, they are always interpreted as a special world. The church interior is a symbolic image of the universe. This interpretation received additional visual expression in painting. The nature of the depiction of figures and scenes also influenced the space of the interior, giving it a look different from the real space of nature.Since Christian worship, unlike pagan rituals, was performed inside the temple, the Byzantine architects were faced with the task of creating a temple with a large room in which a large number of people could gather. The cross-domed type of the temple fully met these requirements.

a). Byzantine cross-domed church

The most successful type of temple for Byzantine worship was a shortened basilica , crowned with a dome, and, according to the Apostolic decrees, facing altar to the East. This composition was called the cross-dome.

|

||

|

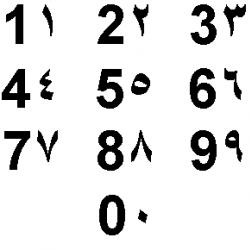

In the classical cross-domed church, the building, square in plan, was divided by rows of pillars or columns into naves - inter-row spaces going from the entrance to the altar. Naves, as a rule, were 3, 5 or 7, and the width of the central nave was twice the width of the side ones. Exactly in the center of the building in the central nave, four main pillars were symmetrically located, carrying dome . These pillars singled out another nave in the space of the temple - transverse or transept . The square dome space between the main pillars, which is the intersection of the central nave and the transept, is called middle cross . Arches carrying semi-cylindrical (barrel) vaults were thrown from the pillars to the walls. On the four main pillars rested a drum with light windows supporting the main dome of the temple. From 4 to 12 smaller domes could coexist with the central dome (the main dome symbolizes Christ, 5 domes - Christ with the evangelists, 13 domes - Christ with the apostles).

Entrance to the temple, framed portal , located on the west side. If they wanted to give the building a more elongated rectangular shape, they added narthex . The narthex was necessarily separated from the central part of the temple - naosa - a wall with arched openings leading to each of the naves.

On the east side was altar

where the most important part of Christian worship took place. In the area of the altar, the wall stood out with semicircular ledges - apsides

(apses), covered semi-domes - conchami

.

If the dome symbolized the heavenly Church, then the altar symbolized the earthly Church. The altar housed throne

- the dais on which the sacrament took place Eucharist

- Transubstantiation of the Holy Gifts (transformation of bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ). Later, north of the altar, they began to arrange altar

(also with a throne, but smaller), and to the south - deacon

- a room for the storage of liturgical vessels and clothes.

Approximately from the 4th century, the altar began to be separated altar barrier

(the device of the first altar barrier is attributed to St. Basil the Great). The barrier separated the clergy from the laity and gave the Eucharistic action a special solemnity and mystery.

The interior decoration, the painting of the temple had to reflect the whole essence of Christian teaching in visual images. The characters of the sacred history in the mural of the temple were placed in a strict order. The entire space of the temple was mentally divided into two parts - "heavenly" and "earthly". In the "heavenly" part, under the dome - the kingdom of Christ and the heavenly host. On the drum of the temple, the apostles should have been depicted, on the main pillars - the four evangelists ("pillars of the gospel doctrine"). In the apse, in the center of the "earthly" part of the temple, the Mother of God was depicted (as a rule, Orantu ), the intercessor of all people before God. The northern, western and southern parts of the temple, as a rule, were painted in several tiers, and the upper tiers were filled with scenes from the earthly life of Christ, miracles and passions. In the lower tier, at the height of human growth, they wrote the Fathers of the Church, the martyrs and the righteous, who, as it were, together with the parishioners offered up a prayer to God.

The cross-domed composition became widespread both in Byzantium and in the zone of orthodoxy that developed around it, especially in Russia. The temple shown in the figure is a Russian temple that fully meets the Byzantine architectural canon, but at the same time has purely Russian features (for example, an onion-shaped dome is characteristic of Russian architecture, Byzantine architects preferred semicircular domes).

3. ² Golden age ² empire.

If at first it was really difficult to draw a line separating them between early Christian and Byzantine art, then by the beginning of the reign of Justinian (527-565), the situation changed. Not only did Constantinople largely regain political dominance over the West, it was also beyond doubt that it had become the "capital of art". Justinian himself, as a patron of the arts, had no equal since the time of Constantine. What he ordered or executed with his support strikes with truly imperial grandeur, and we fully agree with those who called this time the “golden age”.

The first major Byzantine construction site in Constantinople is Church of Sergius and Bacchus. It was built around 527 - the year of Justinian I's accession to the throne and is one of his first construction projects. There is an assumption that the building was built by Anfimy and Isidore, the famous architects of Sophia of Constantinople, which is confirmed by the similarity of these temples. Indeed, the Church of Sergius and Bacchus is one of the main predecessors of Sophia.

The general system of the Church of Sergius and Bacchus is based on the centric composition used in previous centuries in Syria and Asia Minor. The church in Esra in Syria (515) was built 12 years earlier than the church of Sergius and Bacchus and is a work that summarizes the achievements of the architects of the previous period in the creation of centric buildings. It is an octagon inscribed in a square. Corner niches serve as a transition between them. Eight pillars carry the dome. They divide the inner space of the temple into the central part and the bypass surrounding it. In the church of Sergius and Bacchus, the same system was used, but complicated by the fact that between the pillars placed alternately rectangular and semicircular in terms of exedra. Thanks to them, the central octahedron, crowned with a dome, is more organically connected with the square of the plan.

It is not known exactly how the service took place, but, apparently, it was the space under the dome that was the main receptacle for those present. The appointment of the building as a court church indicates that the emperor with his family and courtiers were in its central part during the service.

Inside, the dome dominates everything else. Exedra are small. Against the background of the internal bypass, the dome space clearly stands out. Due to the openwork of the colonnades, the surrounding gallery is clearly visible from the middle of the interior.

Initially, the dominance of the dome was expressed even more clearly with the help of a golden mosaic that completely covered its huge inner surface.

Quite powerful domed pillars are reminiscent of earlier buildings in Syria and Asia Minor. A number of compositional techniques, including the existing marble cladding, which reached the base of the vaults, somewhat lightened the mass of the pillars. This was also facilitated by a slotted stone cornice, passing at the level of the capitals of the columns of the lower tier and connecting all parts of the building together.

The details of the interior of the Church of Sergius and Bacchus bear traces of the ancient tradition, which is expressed in a rather strong convexity of the broken cornice and in some sculptural lower capitals. However, the widespread use of the cut-out ornament speaks of the desire for light openwork forms.

Church of San Vitale in Ravenna is an outstanding building of the same time (526-547). It has an octagonal plan and is crowned with a central dome.

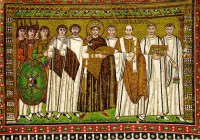

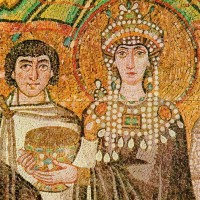

Under the upper row of windows in the wall of the main nave there is a series of semicircular niches that capture the territory of the side aisles, they seem to be combined, creating a new, unusual spatial solution. The side naves are made two-story - the upper galleries were intended for women. The new, more rational design of the vaults made it possible to place large windows along the entire facade of the building, filling its internal volumes with light. The originality of external architectural forms corresponds to the rich interior decor of a very spacious interior. To the left and to the right of the altar are placed mosaics, on which we see Justinian, his courtiers, the local clergy present at the service. On the opposite wall is the Empress Theodora with her court ladies. These mosaics indicate that the emperor was also directly involved in the construction of San Vitale.

4. The greatest of the architectural monuments of Byzantium is St. Sophia Cathedral.

Sophia Cathedral in Constantinople (532-537) - the most grandiose and most outstanding work of Byzantine architecture - is one of the most significant monuments of world architecture. It is on him that the main attention should be paid when studying Byzantine architecture.

The builders of Constantinople Sophia - Anthimius from Thrall and Isidore from Miletus were outstanding engineers and architects, very developed, highly educated people who owned the entire amount of knowledge of their era. Both of them had a very broad architectural and general outlook. This allowed them to freely choose in the past what could be useful in the construction of the greatest building of our time.

Sophia Cathedral in Constantinople is one of those works of architecture that are deeply connected with the past, in which all the main achievements of the architecture of previous eras are taken into account, but in which the new dominates. A new purpose, new constructive techniques and new architectural and artistic features prevail in Sofia so much that they come to the fore, pushing the traditional and overshadowing it with themselves.

Sophia of Constantinople was the main building of the entire Byzantine Empire. It was a church at the public center of the capital and a patriarchal church. Due to the fact that in Byzantium religion played a huge role in the life of the state, Sofia was the main public building of the empire. This outstanding significance of Sophia was very clearly expressed in the choice of a place for her and in the very setting of her among the dominant buildings of the Byzantine capital. The main streets of the city converged from several city gates to the main street (Mesi). The latter ended with Augustion Square, which overlooked Sofia, the Hippodrome and the Grand Palace of the Byzantine emperors. This whole complex of public buildings, among which Sophia dominated, was the ultimate goal of movement along the city streets, the opposite end of which branched into the main roads of the European part of the empire. Augustion and the buildings adjacent to it occupied the top of the triangle on which Constantinople was located, located at the tip of the European mainland, advanced towards Asia. It was the intersection of two main trade routes of antiquity and the Middle Ages: the west-east land route that connected Europe with Asia, and the north-south sea route (the so-called ²from the Varangians to the Greeks ²) that connected Scandinavia with the Mediterranean Sea. Sofia was the largest, most compact and massive architectural structure not only on Augustion, but throughout the capital. She marked a place that could really be called the center of the world in early Byzantine times.

It did not stand in isolation, but was surrounded by a variety of buildings and courtyards. It could not be directly bypassed. Visible only from the courtyards and streets adjoining it, it towered over neighboring buildings, colonnades of peristyle courtyards and squares. Only its eastern facade was completely open: the apse was visible to the top. Such an arrangement in the ensemble gave a particularly great architectural significance to the crowning parts of the building. It was they who were visible above other buildings when approaching Sofia; From a distance, they crowned the center of the capital, and even the architectural ensemble of the whole of Constantinople.

The new typological solution of Sophia, found by Anthimius and Isidore, was based on the requirements of everyday life, which were reflected in the organization of the plan of the cathedral. Sophia was a building in which the broad masses of the people, flocking to the cathedral from the streets and squares of the capital, met with the highest aristocracy and bureaucracy of the empire, headed by the emperor and the patriarch, coming out of the neighboring Grand Palace. These meetings were accompanied by complex theatrical ceremonies of a religious nature. The sequence of actions in a symbolic form depicted the history of the world, as it is interpreted in the scriptures. Conditional movements and actions were carried out in a strictly regulated manner by numerous clergymen of various ranks, headed by the patriarch and the emperor. They were dressed in rich clothes made of beautifully selected valuable fabrics. Through solemn processions and strictly fixed exclamations and chants, the most significant moments in the history of mankind were depicted, which were concentrated around the history of Christ.

In order to hold such services, it was necessary to create a building with a large free central space for ceremonies and accommodating spacious surrounding rooms for a huge number of spectators. In the center there should have been a pulpit-pulpit - the place of the focus of ceremonies, depicting in the course of action either the cave where Christ was born, or the mountain on which he was crucified, etc. The central part of the building was supposed to have an appendage in the form of an altar, depicting the kingdom of heaven, while it itself represented the earth, where the depicted events took place. There was constant communication between earth and sky, but the altar was separated from the audience by a low barrier that hid the heavenly world. Those present could look into it only periodically, when the gates opened. In front of the main room, there should have been a more closed part of the interior, in which the participants in the processions could gather before leaving for the main room.

Similar functional requirements, which arose in a less developed form in the previous period, gave rise to the architectural type of the domed basilica, which was chosen for the main temple of the Byzantine Empire by Anthimius and Isidore. However, the colossal size of Sofia, the special crowding and originality of the ceremonies that took place in it - all this forced the architects of Sofia to rethink the architectural type of the domed basilica itself and organize it in a new way, taking into account the Roman architectural experience, well known to them.

Anfimy and Isidore, both from Asia Minor, based their construction on the Asia Minor type of domed basilica, where the central part of the building was covered with a dome. This introduced the beginning of centricity into the building, as a result of which the basilica was greatly shortened, as if pulling itself up to the dome. Such a domed basilica contained the main necessary premises: the main central room, to which the altar part adjoins, two-tiered galleries for spectators and a narthex.

The question arises about the main difference between such domed basilicas - the predecessors of Sophia - from the ancient Christian basilicas of Rome - these first land-based Christian churches in the western capital of the empire after the official recognition of the new religion. The difference lies in the addition of the dome. In the ancient Christian basilica, everything was directed to the altar, which was the main, the only center of the interior. In the domed basilica, along with the altar, there is a second center under the dome. This indicates a profound change in the very concept of a church building, due to a change in religious ideology.

With the further development of the domed basilica, the dome did not supplant the altar apse. However, gradually it became the main visible center of the interior. The centric principle introduced by him became stronger and stronger. The basilica shortened and pulled itself up to the dome. As a result, the main architectural focus was shifted from the apse to the dome, and the building turned from a basilica into a centric structure.

The main difficulty that architects faced when designing Sofia was that the domed basilicas that existed in the Byzantine world were of very modest size, while Sofia was supposed to be a grandiose structure. Another difficulty, purely constructive, was that the wooden ceiling was not suitable for an interior with a diameter of more than 30 m. The dome had to be made of stone for reasons of ideological and artistic order. It was supposed to depict the vault of heaven, crowning the earth - the central part of the interior. The whole building inside had to look uniform, it had to be all stone from the base to the locks of the vaults.

Vaulted buildings are very large sizes were well known to Anthemius and Isidore. Apparently, their architects took them as a model, choosing the most grandiose and wonderful buildings. The plans of the architects corresponded to the most grandiose Roman basilica, at the same time vaulted, and the most prominent domed building, and it turned out to be possible to combine the features of these two structures. These two buildings were the Basilica of Maxentius and the Pantheon. If in our time an architect were asked to name two of the most outstanding Roman buildings, he could not have chosen better.

Sophia's plan clearly indicates that it was the Basilica of Maxentius that was the basis of her system. The plan is divided by four intermediate pillars into nine parts, so that the central nave became three-part. From the domed basilicas, the architects borrowed choirs, which allowed them to greatly increase the capacity of the side aisles intended for worshipers.

The most outstanding architectural achievement of the two builders of Sofia is the technique by which they linked together in their work the Basilica of Maxentius and the dome of the Pantheon. This technique is one of the most daring and successful ideas in the architecture of the past. This ingenious solution embraced the functional, constructive and artistic aspects of architecture at the same time. It resulted in a surprisingly full-fledged complex architectural image.

Anthimius and Isidore invented a system of semi-domes linking the dome of Sophia with its basilica base. This system includes two large semi-domes and five small ones. In principle, there should have been six small semi-domes, but one of them was replaced by a barrel vault over the main entrance to the central part of the interior from the narthex. This is a retreat from common system splendidly highlighted the main entrance portal and two smaller portals on its sides. Through these portals, processions entered from the narthex, the emperor and the patriarch passed through the main portal. The semi-domes perfectly connected the basilica and the dome. This created a domed basilica of a completely new type, the only representative of which is Sophia of Constantinople.

The compositional technique used by Anthimius and Isidore fixes the location of the dome in the very center of the building. In the domed basilicas of the previous time, the location of the dome constantly fluctuated due to the possibility of lengthening or shortening the barrel vaults located to the west and east of the dome. Usually the altar still attracted the dome.

In Sofia, half-domes create similar shapes to the east and west of the dome, having the same depth. Thanks to this, the dome cannot be moved from its place and confidently marks the center of the building. At the same time, the conch of the apse is included in the system of semi-domes. This means that the altar part is naturally tied to the dome and to the main part of the interior. Thus, an architectural system was created that legitimized both centers of Sofia - the dome and the apse, the pulpit and the altar. As a result, the system of semi-domes perfectly connected the orientation towards the altar of the basilica and the centricity of the domed building. In Sofia, the basilica and the dome are internally organically connected with each other. This is really a real domed basilica, the crown of the whole development of this architectural type.

No less significant role was played by the half-dome of Sofia in terms of architectural and constructive. The huge dome of Sofia creates a very strong thrust. In the southern and northern directions, the thrust is extinguished by powerful pillars, two on each side. The vaults of the side aisles, located in two tiers, participate in the repayment of the expansion of the dome in the same direction. In the eastern and western directions, the thrust is extinguished by semi-domes. The outstanding significance of this solution lies in the fact that the semi-domes fulfill their constructive role without cluttering up the interior of the main part and without violating its integrity.

The artistic significance of the system of the dome and semi-domes of Sofia is also remarkable. This system simultaneously solves a whole range of artistic problems.

Half domes together form geometric figure approaching an oval. It is with this that they create an intermediate link between the basilica and the centric building. In principle, three figures inscribed into each other are formed, gradually turning into one another: the rectangle of the main outline of the plan, the oval of the semi-domes and the circumference of the dome. The oval serves as a transition from a rectangle to a circle.

In a concrete spatial expression, this scheme takes on a particularly complete and organic form. The semi-domes continue the rhythm of the growth of the interior space from the side aisles to the central one. As the semi-domes develop in the direction of the dome, the space grows up to the culminating point in the center. In the opposite direction, the central space under the dome gradually falls in both directions and is further replaced by the space of the side aisles.

The comparison between Sophia and the Pantheon reveals a fundamental difference between them in the interpretation of the dome. In the Pantheon, the under-dome space is static, it is a closed piece of space, huge in its compactness, firmly outlined by walls and a dome. In Sofia, the central interior space is light, airy and dynamic. Openwork colonnades connect it with all surrounding neighboring rooms. The space grows from all sides towards the crowning dome. The dome itself appears and, as it were, is built in time before the eyes of the viewer; it gradually develops from semi-domes. The latter cover only part of the interior, while the dome closes the entire interior from above.

The huge central space of Sofia and the much lower and cramped side aisles divided into two tiers are arranged in different ways and contrast with each other. At the same time, they complement each other and, combined, form a single architectural image.

The side naves intended for the people look like palace halls. As studies of the Grand Palace of Constantinople show, this similarity really took place and, moving from the palace to Sofia, noble parishioners saw in front of them, as it were, a continuation of the suite of palace halls. Each side nave of Sofia is perceived as a picturesque space somewhat unclear in its boundaries and dimensions. The transverse walls with arches cover not only the outer walls, but also the colonnades of the middle nave. As you move along the nave, the transverse walls and columns form a variety of combinations, visible from various angles and diverse mutual intersections. When larger pieces of the outer walls are exposed, their openwork character emerges. Below, they are denser, as they are cut through only by three large windows in each division of the wall. Above these windows, solid glazing opens under the semi-circular curve of the vault, so that light flows freely into the interior. On the opposite side of the nave, this corresponds to the colonnades opening into the middle nave.

The overall picturesqueness of the side aisles is enhanced by the marble cladding rising to the base of the vaults and protected from above by a marble slotted cornice, as well as the gold of the mosaics covering the vaults. Due to the strong dissection of space and numerous transverse walls, different parts of the premises are illuminated differently. The degree of illumination is deeply thought out and accurately weighed by the masters.

In relation to such compositions, one researcher successfully applied the term "light organ": he likened to music the harmonic composition of shades of light and shadow in architecture. Color effects are combined with this. The marble slabs of the wall cladding and the marble of the columns are finely matched. Pale pink and complementary pale green shades dominate. In general, a single gentle tone is formed. The chiaroscuro of the cut-out cornices and the light ornamental colored frames of the golden mosaic surfaces complete the overall effect, deeply thought out and unusually harmonious.

Due to the relatively low height of the side aisles, their dimensions are well related to the height of a person. To a certain extent, the columns bearing vaults have an order principle inherited from antiquity. They come forward and play the role of a connecting element between the human figure and the interior space. Leaning on the columns, the eye reads the architectural composition as a whole.

The structure of the central nave is based on other compositional principles. The interior of the main part of Sofia has gigantic dimensions and a distinct spatial form. The space of the main premises of Sofia is clearly limited by a strict linear frame and straight and concave surfaces. The main structure is simply and clearly indicated by vertical lines merging into the lines of arches and the circumference of the dome ring. Pavel Silentiary, a contemporary of Justinian I, figuratively says that the dome of Sophia looks like it is floating in the air, as if it is suspended on a chain from the sky.

Conclusion: early Byzantine architecture gave rise to the formation, first, of an independent variety of Byzantine architecture, and then to the creation, on an ancient basis and a Byzantine basis, of its own architecture. The greatest merit of early Byzantine architecture was that it gave a powerful impetus to its development in the future.

II . Middle Byzantine architecture

2. The main features of the Middle Byzantine architecture

The transition from the early Byzantine period to the Middle Byzantine period was associated with the tragic time of Byzantium's desperate resistance to external invasions and with profound changes within the empire. The Byzantine peasantry became more and more enslaved, the power and power of individual feudal lords greatly increased. In this regard, instead of large state buildings, they began to build mainly small parish and monastery churches with small side chapels in the choirs or below - home prayer houses of the customers who built the building.

In the history of Byzantine architecture, the question of the planning of a city, a country feudal estate, a monastery, and a rural settlement has been studied very little. At this time, there was no construction of new cities, but much attention was paid to the construction of fortresses. However, it was reduced almost exclusively to the restoration of old cities and the repair of fortress walls erected earlier.

Regular development, inherited from antiquity, was increasingly replaced by unplanned development on the model of rural settlements. However, on the basis of unplanned, spontaneous development, freely arranged settlements and city blocks arose with an asymmetric arrangement of buildings and a curvilinear outline of streets. Monumental buildings stood in isolation, mostly on elevated places. They could be walked around, they often occupied the central part of city squares. This explains the more closed nature of their three-dimensional architectural composition.

A new feature characteristic of the Middle Byzantine architecture in comparison with the previous stage in the development of Byzantine architecture was the small size of buildings. Church buildings, which continued to predominate in construction, were necessary primarily for the privileged. They have an intimate dimension. Already in the XI - XII centuries. there is a tendency to create separate chapels inside the churches for an even narrower circle of feudal lords. Instead of the majesty of Sophia Cathedral in Constantinople and other early Byzantine buildings, dwarf proportions appear, which give parts of buildings and even buildings as a whole the character of miniature structures.

This does not mean that the Middle Byzantine architecture did not create anything of its own. It reflects the most opposite tendencies. Colliding with each other, they formed something new.

The main achievement of the Middle Byzantine architecture was the creation of a cross-domed architectural system. This system originated and took its first steps in the early Byzantine period, but it reached its full development, its maturity only in the Middle Byzantine architecture. The cross-domed buildings of Byzantium make an exceptionally strong impression with their surprisingly balanced composition, which is aimed at revealing the main spatial coordinates. The interior of the cross-domed building is divided into nine spatial cells, which are strictly subordinate to each other and form a visual hierarchical system of space.

In the entire world architecture of previous periods, there was nothing that could be equated with the Middle Byzantine cross-domed system. Its significance lies in the fact that it was the first to develop a grouping of spatial cells.

2. Constantinople architectural school in the Middle Byzantine period

Ordinary residential buildings of Constantinople and the capital's palaces of the Middle Byzantine period have not reached us. The layout of the latter remains unknown. Their appearance can be judged to some extent by the palace buildings that have been preserved in other cities.

Closest to the palaces of Constantinople were the richest palaces of Venice. For example, the palace of Fondaco dei Turchi was built in imitation of the most luxurious Middle Byzantine buildings in Constantinople. Colonnades occupying the entire street facade of the palace are characteristic. The main street of Constantinople and some of its other streets were completely built up with similar buildings. They formed solid rows of columns that framed the street on both sides. On the facade of the Fondaco dei Turchi, two towers are marked, marking the corners of the building. This indicates the origin of this type of Venetian and Constantinople palaces from Roman buildings with a portico between the corner risalits.

Many of the Middle Byzantine church buildings of Constantinople have survived, but they have come down to us in a highly distorted form.

The main building of Constantinople that has come down to us is a wonderful complex of three merged churches of the Pantokrator monastery. It consists of an earlier northern church, a slightly larger southern church attached to it somewhat later, and a domed room located between them and connecting them. It is known that this single-nave, single-dome chapel is the tomb of Emperor Manuel Komnenos (1143-1180), built during his lifetime. This makes it possible to date both churches to which the chapel was attached. They were raised before her. The south church was built after the north one, as its stair tower, located to the north of the narthex, leans against the south stair tower of the north church. The earlier dating of the northern church is also confirmed by the fact that in its architecture it is somewhat more archaic than the southern church. The architectural type of the northern church is an intermediate version between the five-nave and three-nave cross-domed buildings.

The southern church was originally a large five-nave cross-domed building. Both churches of the Pantokrator Monastery are complex cross-domed buildings. The peculiarity of both of these buildings is the absence of walls separating the side apses from the main part of the interior. This slightly strengthened the altar part. The peculiarity of the southern church is, in addition, a narthex, open to the outside with a triple opening, with marble frames inserted into the openings. This suggests that the building was designed for ceremonial entrances, probably the emperor himself.

Also, the building that has come down to us is the Palace of San Marco in Venice. Western European architects of various eras were influenced by San Marco, who was one of the strongest conductors of Byzantine influence in Western Europe. The complex and at the same time deeply integral spatial structure of San Marco attracted the special attention of Western European architects. Created on the basis of all the previous development of Byzantine architecture, organically incorporating the heritage of Greek and Roman ancient architecture, the structure of San Marco is a wonderful link between the architecture of antiquity and Western Europe.

3. Eastern Byzantine architectural school in the Middle Byzantine period

The few eastern regions of the Byzantine Empire that remained in the state were in the Middle Byzantine period under the constant threat of enemy invasions. As a result, construction here was insignificant in volume. The main attention here was paid to the restoration and some expansion of the city fortifications and to the repair of those buildings that could still serve. Industrial and residential buildings of that time have been preserved in very small numbers. This is explained by the fact that the subsequent conquest by the Turks led to the destruction of buildings or to a change in the very purpose of buildings, which was associated with their restructuring. Only large secular and church landowners, as well as the richest citizens, could build new residential buildings for themselves. These were just a few buildings. Churches were the main public buildings at that time. Where possible, they were also built anew. At the same time, their architecture differed in a number of features from the capital's religious buildings.

As an example big city in Asia Minor, which existed as part of the Byzantine Empire for almost the entire Middle Byzantine time, Nicaea should be cited. The walls of the city and the basic system of street planning have been preserved from antiquity and from the early Byzantine period.

Another example of a Middle Byzantine city is Korikos, located on the southern sea coast of Asia Minor, in Cilicia. The city is interesting because it is part of a system of fortresses built in 1104 by Admiral Eustathius to protect the Byzantine state.

For the Middle Byzantine period, the creation of separate fortified points to protect the city is very characteristic, in contrast to the early Byzantine period, when entire cities were surrounded by a large ring of walls.

The great buildings of the major cities of the eastern regions of the Byzantine Empire are well represented by the cathedral at Mayafarkin in Mesopotamia. This is a rare Eastern Byzantine representative of the architectural type of the five-nave cross-domed system.

Differences from the buildings of Constantinople are clearly visible in building materials, architectural structures and artistic composition.

Conclusion: medieval architecture still has a single character. Its unity is based on the fact that it is dominated by a centric monumental building crowned with a dome. It is the dome that is the favorite form of Byzantine architects, which they constantly used and varied many times. The architectural development of the dome is the most valuable content of Byzantine architects.

III . Late Byzantine architecture

The short Late Byzantine period is characterized by rather significant changes in architecture. The Byzantine Empire was living out its last days. The late Byzantine period corresponded in time to the era of Gothic and the birth of the Renaissance in Western Europe and the era of the formation of Russian centralized state in Eastern Europe.

By the XIV century. refers to the best-preserved palace building of Constantinople - the building that the Turks called Tekfur-Serai. At this time, the Grand Palace of Constantinople was abandoned by the courtyard, which was located in the Blachernae Palace, located on the highest point of Constantinople.

Tekfur Serai is a small part of the Blachernae Palace. This is a summer hall and dining room, located on the third floor and built over the earlier walls with which the Blachernae Palace was fortified from the side of the city.

A distinctive feature of the Tekfur masonry, by which one can immediately identify the late Byzantine building of Constantinople, is the inclusion of stone in the masonry of arches.

For the last period of Byzantine architecture, the rich decorativeness of the facade of Tekfur is very characteristic. The laying of the walls itself has a picturesque character. It effectively alternates between narrow red stripes of brick and solid stripes of warm yellow stone.

The general appearance of Tekfur-Serai is lively, picturesque and very elegant. Shifts, openings, arcades, general asymmetry and, in particular, the yellow-red brick-and-stone decoration created with the help of the masonry itself, greatly decorate the building.

In late Byzantine times, even the best buildings of Constantinople reflected the lack of funds due to the difficult economic situation of the Byzantine Empire in the last period of its existence. Almost all the larger buildings of Constantinople at the end of the 13th century. and XIV-XV centuries. are the restoration of buildings of an older time, usually accompanied by the addition of new parts or a superstructure. The general pictorial character of late Byzantine architecture is associated with similar extensions to an already existing building.

One of the first buildings after the liberation of Constantinople from the Crusaders was the tomb of the Palaiologos dynasty, attached to the Middle Byzantine church of the Lipsa monastery. The newly built complex consists of a peristyle church, symmetrically surrounded by a gallery with burials in niches. All these parts are picturesquely stuck to the old building.

An outstanding work of late Byzantine metropolitan architecture is the church of the monastery of Chora, built by the court nobleman Theodore Metokhit. The Turks turned it into a mosque called Kahriye-Jami. Chora Monastery Church is a reconstruction of an earlier building. From the latter, only fragments of the middle part and three apses remained. In late Byzantine times, cells were added, converted from the northern nave, a narthex, exonarthex and a special church extension from the south in the form of a very elongated nave ending in an apse. A feature of the building is the asymmetric arrangement of three small domes in relation to the main dome. Two of them are above the narthex, the third is above the southern church.

In late Byzantine times, a very peculiar The final stage development of Byzantine architecture. The very nature of the reconstruction of old buildings and the addition of new parts to pre-existing premises gives rise to a picturesque beginning. It is expressed in the free grouping of parts characteristic of residential architecture. In late Byzantine times, the location of buildings on hillsides was very common, so that some of their walls were higher, while others went into the ground.

Conclusion: in it hard time funds were only enough to restore and partially rebuild old buildings. A taste was formed for additions, for the addition of new small premises, for the gradual expansion of buildings in different directions in parts, as is usually the case in residential buildings, expanded as new needs and opportunities arise. Late Byzantine architecture has all the features of the final stage of development of an obsolete historical cycle. The last stage in the development of Byzantine architecture on the eve of the fall of the empire reveals mainly the obsolescence of the traditional principles of Byzantine architecture and contains only very insignificant sprouts of a possible further development, which was never destined to materialize.

Conclusion

As a result of the studied topic, we can conclude that Byzantine architecture made a very large and significant contribution to the treasury of world architecture. His main achievement was the remarkable development of a centric architectural composition based on the overlapping of the main part of the building with a dome. The dome is the main theme of Byzantine architecture.

The study of early Byzantine architecture shows that Sofia Cathedral occupies a completely exceptional place in it. It would be wrong to assume that there were no repetitions of Sophia because Sophia was an accidental phenomenon in the history of Byzantine architecture. It could not be repeated because the task to build the main church of the Byzantine Empire could not be repeated. Precisely as a building that met this task and unusually fully reflected the Byzantine worldview, Byzantine statehood and the principles of Byzantine art, Sophia in Constantinople is the most characteristic work of all Byzantine architecture. Works that especially fully reflected their era and the worldview of the culture and people that gave rise to them and, nevertheless, remained unrepeated, also arose in other eras. Such, for example, is the Cathedral of the Intercession (Vasily the Blessed) in Moscow.

Sophia Cathedral is, first of all, a monument of its era, which had an extraordinary power of influence not only on contemporaries and the next generations, but also on people of subsequent centuries and even the next millennium.

As for the individual elements of Sophia of Constantinople, for example, sails, internal marble wall cladding, zakomar and many others, they had a very great influence both on the Byzantine architecture of the subsequent time, and on the architecture of other countries.

It is especially significant that Sophia served in a certain sense as the starting point for the development of the cross-domed system of later times. In this regard, it is also a deeply natural and necessary link in the development of Byzantine and all world architecture.

A characteristic feature of Byzantine architecture are domes located on a square base, which, unlike the rotunda, can be expanded with extensions, domes resting on four pillars, domes on drums. The reason that the centric domed building was in the center of attention of Byzantine architects was the Christian religion. Christian churches with all their appearance should have reminded of another world. According to Byzantine architects, it was the centric domed building that corresponded to the Christian faith. The cross-domed system was a well-known universal method of architectural composition, covering the functional, constructive and artistic aspects of architecture. This method opened up the opportunity for architects of that time and subsequent eras to widely vary and develop the centric dome composition - one of the most valuable and versatile achievements of architecture of all times and peoples.

Byzantine architecture influenced Muslim architecture, especially Turkish architecture, when direct reproductions of Sofia began to appear one after another in Istanbul.

Byzantine architecture was a kind of key point in the development of architecture between antiquity and Europe in the Middle Ages and modern times.

The influence of Byzantine architecture on the development of architecture in Eastern and Western Europe was very great, and so far it has not been sufficiently appreciated. With regard to Eastern Europe, mainly Russia, no special evidence is required, since the Byzantine origins of Russian architecture are fairly generally recognized.

Much in gothic architecture explains the influence of Byzantine architecture, for example, the tracery of Gothic cathedrals, which was the development characteristic feature Sophia of Constantinople, or the system of Gothic canopies that developed from Byzantine prototypes, or, finally, the flying buttresses that arose in Byzantium and then passed to Western Europe.

The influence of Byzantine architecture on the architecture of the Renaissance is especially significant. It affected mainly the centric domed architectural type and can be traced from Brunelleschi through Bramante to Palladio. The influence of the cross-domed system on many outstanding buildings of the Renaissance was carried out partly through a number of Byzantine buildings on the soil of Italy.

If we consider the most outstanding European monumental buildings, then their connections with Byzantium will come out very clearly. These connections were carried out through intermediate links, mainly Renaissance buildings (especially Peter's Cathedral in Rome), but also directly. In the Cathedral of St. Paul in London, the Pantheon in Paris, the Cathedral of the Smolny Monastery, the Kazan and St. Isaac's Cathedrals in St. Petersburg, we will see the basis of the cross-domed system, ultimately of Byzantine origin.

Byzantine architecture was a link between ancient architecture and the architecture of the Renaissance and subsequent times in Europe.

Bibliography

1. Yakobson A.L. Patterns in the development of medieval architecture, Nauka Publishing House, Leningrad, 1985.

2. Goldstein A.F. Architecture, Moscow "Enlightenment", 1979.

3. Kantor A.M., Sidorov A.A. Small history of arts, Moscow "Art", 1975.

4. Stankova Ya., Pekhar I. Thousand-year development of architecture, Moscow "Stroyizdat", 1987.

5. Byzantium and Byzantine traditions, Moscow, 1991.

6. Alpatov M.V. General history, 1948.

7. Dmitrieva N.A. Short story arts.

8. Gombrich E. History of Arts, M., 1998.

9. Lazarev V.N. Byzantium and Old Russian Art, M., 1978.

10. Shishova N.V. History and cultural studies.

11. Guidelines ed. Shishova - Historical and cultural features of Byzantium, 1994.

12. Likhacheva V.D. Art of Byzantium, M., 1981.

13. Medvedev I.P. Essays on the history and culture of the late Byzantine city, M., 1973.

14. Udaltsova V.V. Byzantine culture, M., 1988.

Details Category: Fine arts and architecture of ancient peoples Posted on 28.01.2016 16:53 Views: 6896“Byzantium created a brilliant culture, perhaps the most brilliant that the Middle Ages knew, indisputably the only one that until the 11th century. existed in Christian Europe.

Constantinople remained for many centuries the only great city of Christian Europe, unparalleled in splendor. With its literature and art, Byzantium had a significant impact on the peoples around it. The monuments and majestic works of art that have remained from it show us the full splendor of Byzantine culture. Therefore, Byzantium occupied a significant and well-deserved place in the history of the Middle Ages ”(Sh. Diehl“ The Main Problems of the Byzantine Empire ”).

Byzantine artistic culture became the ancestor of some national cultures, including, for example, ancient Russian culture.

The Byzantine Empire (Byzantium) was formed in 395 as a result of the final division of the Roman Empire after the death of Emperor Theodosius I into western and eastern parts. After 80 years, the Western Roman Empire ceased to exist, and Byzantium became the historical, cultural and civilizational successor ancient rome for almost 10 centuries.

In 1453, the Byzantine Empire finally ceased to exist under the onslaught of the Ottomans (Ottoman Empire).

The permanent capital and civilizational center of the Byzantine Empire was Constantinople, one of the largest cities in the medieval world. In the South Slavic languages it was called Tsargrad. Officially renamed Istanbul in 1930

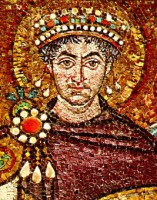

Justinian I. Mosaic from the Basilica of San Vitale (Ravenna)

Byzantium achieved the position of the most powerful Mediterranean power under Emperor Justinian I (527-565).

General characteristics of Byzantine fine art

I-III centuries - early Christian period(the period of pre-Byzantine culture).

4th-7th centuries - early Byzantine period. It was called the "golden age" of Emperor Justinian I (527-565).

VIII-early IX centuries. - iconoclastic period at the direction of Emperor Leo III the Isaurian (717-741). He issued an edict banning icons.

867-1056 - period of the Macedonian Renaissance. It is considered the classical period of Byzantine art. 11th century - the highest point of flowering of Byzantine art.

1081-1185 - period of conservatism. The reign of the emperors of the Komnenos dynasty.

1261-1453 - period of the Palaiologan Renaissance. This is the time of the revival of Hellenistic traditions.

Byzantine architecture

From the first days of its existence, Byzantium began to build majestic buildings. Oriental influences were mixed with Greco-Roman elements of art and architecture. During the entire period of the existence of the Byzantine Empire, many remarkable monuments were created in all areas of the Eastern Empire. Until now, Byzantine motifs can be traced in the art of Armenia, Russia, Italy, France, in Arabic and Turkish art.

Features of Byzantine architecture

The forms of Byzantine architecture were borrowed from ancient architecture. But Byzantine architecture gradually modified them during the 5th century. developed its own type of structures. Mostly they were temple buildings.

Its main feature was a dome to cover the middle part of the building (central-dome system). The dome was already known in pagan Rome and in Syria, but there it was placed on a round base. The Byzantines were the first to solve the problem of placing a dome over the base of a square and quadrangular plan with the help of the so-called sails. ![]() Sail- part of the arch, an element of the dome structure. By means of a sail, a transition is made from a rectangular base to a domed ceiling or its drum. The sail has the shape of a spherical triangle with its apex down. The bases of the spherical triangles of the sails together form a circle and distribute the load of the dome along the perimeter of the arches.

Sail- part of the arch, an element of the dome structure. By means of a sail, a transition is made from a rectangular base to a domed ceiling or its drum. The sail has the shape of a spherical triangle with its apex down. The bases of the spherical triangles of the sails together form a circle and distribute the load of the dome along the perimeter of the arches.

Inside Byzantine churches around the middle dome space, with the exception of the altar side, there was a choir-type gallery (upper open gallery or balcony inside the church, usually at the level of the second floor in the main hall.

In Western European churches, choirs usually house musicians, choristers, and an organ. In Orthodox churches - kliros (singers and readers).

Vladimir Cathedral in Kyiv. Choirs built over the side aisles of the temple

From below, the gallery was supported by columns, the entablature (the beam ceiling of the span or the completion of the wall) of which was not horizontal, but consisted of semicircular arches thrown from column to column.

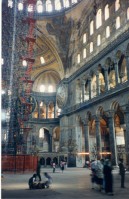

Columns supporting the gallery in the Hagia Sophia

The interior of the building was not distinguished by the richness and complexity of architectural details, but its walls were faced from below with expensive varieties of marble, and at the top, like the vaults, they were richly decorated with gilding, mosaic images on a gold background or fresco painting.

Interior of the Sofia Cathedral

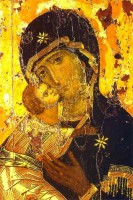

Mosaic image of the Virgin

Hagia Sophia is a masterpiece of Byzantine architecture.

Hagia Sophia (Istanbul)

Former Orthodox cathedral, later a mosque, now a museum; the world-famous monument of Byzantine architecture, a symbol of the "golden age" of Byzantium. The official name of the monument today is the Hagia Sophia Museum.

For more than a thousand years, St. Sophia Cathedral in Constantinople remained the largest church in the Christian world (until the construction of St. Peter's Cathedral in Rome). The height of the St. Sophia Cathedral is 55.6 m, the diameter of the dome is 31 m.

Church of Hagia Irene in Constantinople (Istanbul)

Represents a new for the VI century. type of basilica in the shape of a cross. The vestibule of the church is lined with mosaics from the time of Justinian. Inside there is a sarcophagus, in which, according to legend, the remains of Constantine (the Roman emperor) are buried.

After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the church was not converted into a mosque and no significant changes were made to its appearance. Thanks to this, to this day, the Church of St. Irene is the only church in the city that has retained its original atrium (a spacious high room at the entrance to the church).

Modern church interior

Painting

The main type of painting was icon painting. Icon painting developed mainly on the territory of the Byzantine Empire and countries that adopted the eastern branch of Christianity - Orthodoxy. Icon painting along with Christianity comes first to Bulgaria, then to Serbia and Russia.

Icon of the Mother of God of Vladimir (beginning of the 12th century, Constantinople)

According to church tradition, the icon was painted by the Evangelist Luke. The icon came to Constantinople from Jerusalem in the 5th century. under Emperor Theodosius.

The icon came to Russia from Byzantium to early XII in. as a gift to the Holy Prince Mstislav from the Patriarch of Constantinople Luke Chrysoverg. At first, the Vladimir Icon was located in the convent of the Theotokos in Vyshgorod (not far from Kyiv). The son of Yuri Dolgoruky, Saint Andrei Bogolyubsky, brought the icon to Vladimir in 1155 (which is why it got its name). Kept in the Assumption Cathedral.

During the invasion of Tamerlane in 1395, the revered icon was transferred to Moscow to protect the city from the conqueror. On the site of the “presentation” (meeting) of the Vladimir icon, Muscovites founded the Sretensky Monastery, which gave its name to Sretenka Street. The troops of Tamerlane, for no apparent reason, turned back from Yelets, without reaching Moscow, through the intercession of the Virgin.

In the monumental painting of Byzantium, mosaic.

Byzantine mosaic (5th century)

Mosaic from the time of Justinian I

Sculpture

Sculpture in the Byzantine Empire did not receive special development, because the eastern church did not take a very favorable view of the statues, considering their worship to be in some way idolatry. Sculptural images became especially intolerable after the decision of the Council of Nicaea in 842 - they were completely eliminated from the cathedrals.

Therefore, sculpture could only decorate sarcophagi or ornamental reliefs, book bindings, vessels, etc. In most cases, ivory served as the material for them.

Porphyry Tetrarchs

Four Tetrarchs- a sculptural composition of dark red porphyry (dark red, purple rock), mounted in the southern facade of the Venetian Cathedral of San Marco. The statue was made in the first half of the 4th century. and was part of the Philadelpheion of Constantinople (one of the most important city squares of Constantinople), built next to the Column of Constantine (modern Chamberlitash Square).

Known Diptych Barberini- Byzantine ivory, made in antique style. This depiction of an imperial triumph dates from the first half of the 6th century, and the emperor is usually identified with Anastasius I or, more likely, Justinian I.

Diptych Barberini (5th-6th centuries)

Arts and Crafts

Carving and metalworking were developed, from which embossed or cast relief works were made.

There was another type of work (agemina): on the copper surface of doors or other planes, only a slightly deepened outline was made, which was laid out with another metal, silver or gold. This is how the doors of the Roman basilica of San Paolo Fuori le Mura, which died during a fire in 1823, were made, the doors in the cathedrals of Amalfi and Salerno near Naples.

In the same way, altarpieces, boards for the walls of thrones, salaries for the Gospels, arks for relics, etc. were made.

Byzantine masters were especially skilled in enamel products, which can be divided into two types: plain enamel and partition enamel. In the first, recesses were made on the surface of the metal with the help of a cutter according to the pattern, and powder of a colored vitreous substance was poured into these recesses, which was then fused over a fire and stuck firmly to the metal; in the second pattern on the metal, it was indicated by a wire glued to it, and the spaces between the resulting partitions were filled with a vitreous substance, which then received a smooth surface and was attached to the metal along with the wire by melting.

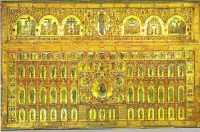

An example of Byzantine enamel work is the famous Pala d'oro(golden altar). This is a kind of small iconostasis with miniatures in the technique of cloisonné enamel, which adorns the main altar in the Venetian Cathedral of St. Mark.

Pala d'Oro

The iconostasis contains many miniatures.

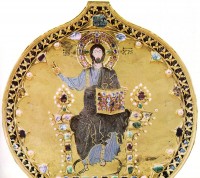

Miniature depicting Christ

Jewelry was also made in Byzantium.

Wedding ring, blackened gold (Byzantium)

At the end of the 4th century, after the division of the Roman Empire and the transfer by Emperor Constantine of his residence to Greek Byzantium, the leading role in political, economic and social life passes to the eastern part. From this time begins the era of the Byzantine state, the center of which was its new capital - Constantinople.

The history of Byzantine architecture is divided into three periods: Early Byzantine (V-VIII centuries), Middle Byzantine (VIII-XIII centuries) and Late Byzantine (XIII-XV centuries). The time of the highest prosperity was the first period, especially during the reign of Justinian (20-60 years of the 6th century), when Byzantium turned into a powerful state that, in addition to Greece and Asia Minor, conquered the peoples of Western Asia, the southern Mediterranean, Italy and the Adriatic.

Continuing ancient traditions, Byzantium also inherited the cultural achievements of the conquered peoples. A deep synthesis of antique and oriental elements is feature Byzantine culture.

The dominance of Christian ideology affected the development of the dominant types of monumental stone construction. The search for the composition of the church in accordance with the purpose of the building was combined with the task of asserting the imperial power. This led to a certain unity of searches and a relative commonality in the development of types of religious buildings, despite regional differences in which the features and traditions were manifested individual peoples.

The most important contribution of Byzantium to the history of world architecture is development of domed compositions of temples, expressed in the emergence of new types of structures - a domed basilica, a centric church with a dome on eight pillars and a cross-domed system. The development of the first two types falls on the early Byzantine period. The cross-domed system of temples became widespread during the period of Middle Byzantine architecture.

The formation of monasteries as a special type of architectural complexes also belongs to the Byzantine era. Out-of-town monasteries are most peculiar, usually representing fortified settlements surrounded by walls, inside which, in addition to the residential and outbuildings of the monks, a vast refectory and dominant building - the church - were built. Buildings and fortifications, most often located asymmetrically on an elevated place, were harmoniously coordinated spatial compositions - ensembles.

The architecture of Byzantium inherited from Rome its achievements in the field of arched and vaulted structures. However, the concrete technique was not accepted in Byzantium; walls were usually built of brick or hewn stone, and also of brick with stone linings or of stone with brick linings. The vaults were made of brick or stone. The ceilings are mostly vaulted, sometimes combined with wooden structures. Along with domes and barrel vaults, cross vaults were widespread. In resting the dome on a square base, an oriental technique was often used - tromps.

The most significant constructive achievement of Byzantine architecture is the development of a system for supporting the dome on four separate pillars using a sail vault. Initially, the dome rested directly on the sails and girth arches; later, between the dome and the supporting structure, they began to arrange a cylindrical volume - a drum, in the walls of which openings were left to illuminate the under-dome space.

This constructive system made it possible to free the interior of buildings from bulky walls and further expand the interior space. The same idea of the spatiality of the interior was served by the method of propping up the spring arches with semi-domes, creating, together with the dome, single space sometimes reaching very large sizes. Mutual balancing of vaults is one of the outstanding achievements of Byzantine architecture. The use of spatial forms, which, due to their geometric structure, have rigidity and stability, made it possible to minimize the massiveness of supporting structures, rationally distribute building materials in them, and obtain significant savings in labor and material costs.

Byzantine architecture

Byzantine architecture