Pencil drawing on the theme of household genre. School Encyclopedia

The emergence of the everyday genre in Russian painting

Everyday genre as one of the types of Russian visual arts received its independent development quite late - in the second half of the 19th century, when realism replaced the classical and romantic direction, striving to study and depict the private and public life of a person. The development of the everyday genre in Russian art is connected, first of all, with the growth of democratic and realistic tendencies, with the appeal of Russian artists to a wide range of areas of folk life and work, with the formulation of important social issues. However, the emergence of the everyday genre began, according to many art historians, as early as the second half of the 18th century, when some artists first began to turn to plots and themes from the life of the common people. In the process of development and formation of the everyday genre in Russian art, its inherent possibilities were determined - from a reliable fixation of the relationships seen in life and the behavior of people in everyday life to a deep disclosure of the inner meaning and socio-historical content of the phenomena of everyday life.

So, first let's define the everyday genre as one of the art forms. According to the definition of the Dictionary of Art History Terms, household genre is a “genre of fine arts, defined by the range of themes and plots from the daily life of a person. Basically, these scenes are depicted on the canvases of painters, but they can also be seen on graphic sheets and in sculpture.

Most researchers consider the second half of the 1760s to be the time of the birth of the everyday genre. At this time, while in Paris, Ivan Firsov created a small painting "In the studio of a young painter" ( Attachment 1). The canvas depicts a little minx girl posing for a boy artist under the supervision of her mother, who persuades her to sit still.

Firsov's name was discovered in 1913 by I. Grabar. It was closed with Losenko's false signature. They probably did this to make it easier to sell the painting: Losenko was a famous master, and Firsov was unknown to anyone. Perhaps the artist would have remained forgotten if not for Grabar.

However, Mikhail Shibanov and Ivan Ermenev are considered to be the creators of the everyday genre.

The year of birth and the year of death of Mikhail Shibanov are unknown. It is believed that he was a serf. Several reliable works by Shibanov have been preserved, among which are portraits of Catherine II and her favorite, Mamontov. However, two works of this artist should be discussed separately. These are "Peasant Lunch" (1774) and "The Feast of the Wedding Contract" (1777).

draws attention to the time of creation of these paintings. Here is what he notes: “The first was written at the height of the peasant war under the leadership, the second two years after its suppression. What prompted the artist to turn to scenes from peasant life, to genre painting, which was considered in those days, and later (before Venetsianov) as something base, unworthy of the artist's brush? Knowing almost nothing about Shibanov, we cannot, unfortunately, answer these questions. But still, one cannot help but think about the dates of the creation of the paintings, in which the sympathy, respect of the artist for the peasants is striking.

Most likely, Shibanov performed the images of peasants from nature. Human dignity is the first thing you pay attention to when getting acquainted with the people portrayed by Shibanov.

In "Peasant Dinner" Appendix 2) impressive truthfully depicted old man, A Young Peasant And An Old Woman. Only the image of a young mother with a child in her arms is presented as idealized. This heroine evokes associations with the face of the Madonna, as it was customary to portray her in the Western European tradition.

The peasant family is about to have dinner. The young members of the peasant family were distracted from dinner. The father got ready, it was a habitual movement to cut bread, but he lingered and, with an affectionate smile, watches as his wife breastfeeds the child. She also forgot about dinner - all her attention to the baby. But on the faces of the elders - calm concentration. They treat food earnestly, seriously, because it is obtained by hard work.

There is no sweetness in the scene. The whole family is perceived as a whole, it is as if united by the heavy, overworked hands of the mother-in-law, who brings the bowl to the table. The situation in the hut is almost not shown, but its simplicity and severity are guessed. The whole structure of the picture convinces us that before us are people who do not live richly, in hard work, but together, with dignity.

"Conspiracy" takes the viewer into a festive atmosphere. But here, too, the artist primarily emphasizes the friendliness in the relations between the peasants. The bride is confused, embarrassed by the importance of the event in her life, and by everyone's attention, and by her unusual festive attire. But everyone has benevolent smiles on their faces, the groom affectionately holds her hand, preparing to seat her in a red corner. On the left side of the picture, a peasant, slyly grinning, holds a damask and a glass in his hands and is preparing to “get down to business”. The guy points his finger at him, inviting the girl sitting next to him to laugh at the impatient. This humorous note enlivens the picture and gives it even more warmth.

In Shibanov's paintings there is no denunciation of serfdom, for which he is sometimes reproached. But this reproach, in my opinion, is unfair. He believes that both works of the artist are true. They do not idealize peasant life. On the back of the paintings, Shibanov wrote that they represent "the Suzdal province of the peasants." Perhaps the artist himself came from the same Suzdal peasants. In any case, his knowledge and understanding of the life and character of the Russian peasant is beyond doubt.

Not only Shibanov addressed this topic. In the exposition of the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg there are two paintings from peasant life, weak in execution, but curious as evidence of the emerging interest in the peasant theme and everyday genre. One of them is "Peasant Feast" by Al. Vishnyakova. There is a large frying pan with scrambled eggs on the table, the hostess puts a dish with pies, glasses sitting at the table in the hands. In 1779, the painting (1739 - 1799) "Feast in the Village" was executed. Here we see a village street, huts, a dovecote, peasants who spree, a dancing learned bear - a common entertainment at folk festivals. The coloring of the picture is very dark, the faces of the peasants are unexpressive. Tankov's works, as noted by most researchers, are shallow in content and do not differ in skill.

However, the watercolors of Ivan Ermenev, who at that time said a completely new word in Russian art, produce a completely different impression.

In the 70s, Ermenev created a series of watercolor drawings under common name“Beggars” (“Singing Blind”, “Peasant Lunch”, “Beggar”, “Beggars”, etc.). The artist usually depicts two full-length figures against the sky, for example, a beggar old woman and a child, a beggar and a guide. Sometimes it is a lonely figure of a beggar or a beggar. A composition of several figures stands somewhat apart, which is called the same as the work of M. Shibanov we are considering above - “Peasant Lunch”.

Let's compare his "Peasant Lunch" with a similar painting by Shibanov. A woman with a child in her arms, a large common bowl, a loaf of bread. But Shibanov's very composition of the picture is such that it brings people together. The same bowl, the mother's hands, as it were, unite, tie those sitting at the table. In Yermenev, people at the table are not united by a common feeling. The common bowl, to which their hands reach, is somehow far from everyone, people do not look at each other. Not only poverty and tiredness, but some kind of stupefaction is felt in them.

In the Beggar Singers watercolor, the old man in the center with a bare dirty leg, the younger beggar on the left with a rag over his eyes evoke a mixed feeling of pity and disgust. A different impression is produced by the old man sitting on the right. He has a large head with rather thick hair, he is bent, but it is clear that he is tall, his powerful hands lie helplessly on his knees. The peasants standing around the singers are listening attentively (with the exception of the two on the right, talking about something), their faces are concentrated and stern.

Studying the artist's works, we can conclude that the artist acutely felt and conveyed some of the gloomy aspects of Russian reality. But he has not yet risen to great artistic and social generalizations.

believes that Ermenev's works are not devoid of some theatricality, since “all of them have the same low horizon, the background is like a huge and deserted space; the silhouette of the characters is shown large, the composition is extremely clear, the characters are static. And yet, looking at these paintings, showing frightening beggars in clothes with huge patches, the viewer feels the true monumentality of the characters. According to one of the researchers, they do not seem to be miserable, outcast people, but a formidable force. So unexpectedly, the work of this master opens up another, almost unknown, facet of the art of the 18th century. This watercolor series is full of gloomy tragedy, despair and hopelessness. In the works of Ermenev, there is absolutely no bright mood, so characteristic of Russian art.

Art historians have tried to evaluate these paintings in different ways. Some saw in the artist's heroes the remnants of the defeated Pugachev's detachments or the beggars after some epidemic, however, perhaps Ermenev wanted to give his works a deeper, philosophical meaning. After all, in Russia they have always been very careful about the poor, who were called "passable kaliks." Perhaps these terrible blind men can be regarded as a symbol of social trouble.

The next stage in the development of the everyday genre of Russian fine art is the first half of the 19th century, when the prosaic motifs of everyday Russian life became the subject of the depiction of truthful and poetic art. By the mid 1840s. artists of the democratic direction turned to the genre of everyday life as a program art, which made it possible to critically evaluate and expose social relations and the moral norms that prevailed in the bourgeois-noble society, and their manifestations in everyday life.

Realistic and democratic trends of the era. with all the completeness and distinctness are reflected in the work of the largest representatives of the domestic genre - and.

The merit of establishing the everyday genre in the romantic style belongs to (1780 - 1847), who turned to genre painting in the 1820s of the XIX century.

The artist captured scenes on his canvases village life and hard peasant labor. The study of reality became the basis of his creative method. As the painter himself said, he strove to "depict nothing other than what it is in nature" and work "without admixture of the manner of any artist." As a result, Russian genre painting was enriched with new images that replaced the idealized, sometimes sentimental, sometimes heroic representatives of the people. The new interpretation of the images was based on a bright and humane view of a person, characteristic of the progressive art of the first half of the 19th century. True, many works are characterized by some idyllism.

So, the central image of his work “On arable land. Spring "(1830s) - a young peasant woman leading a pair of horses harnessed to a harrow ( Annex 3). The artist wanted to tell about the beginning of field work as a joyful, long-awaited event in peasant life. Achieving a mood of festivity, the master probably “dressed up” the heroine in a pink sundress and kokoshnik for this.

Such clothes, of course, enhance the poetic image of the peasant woman. The sundress resembles an antique high-waisted dress, the kokoshnik resembles a diadem. This impression is aggravated by the light, “dancing” step of the figure. The heroine of the picture looks like a revived statue of the goddess Flora, making her triumphal procession through the spring land. The beauty of the impression is also facilitated by the tendency inherited by Venetsianov from Borovikovsky to the range of whitened, brightened tones.

Idyllicity is preserved in many, including later, works by Venetsianov. This suggests that on his canvases the artist primarily sought to embody the ideal of national Russian beauty, which he saw in spirituality and high moral qualities. In this sense, a kind of gallery of peasant types, created by an artist who seeks in his heroes, first of all, peace, spiritual integrity and purity, is indicative. Venetsianov inextricably linked ideas about moral purity and spiritual health of a person with the image of a simple Russian peasant.

In the early 1820s, he painted the painting "Barn" ( Appendix 4). The impetus for its creation, according to the artist, was familiarity with the painting by Francois Granet "Interior view of the Capuchin monastery in Rome", located in the Hermitage. “This picture,” the artist wrote, “produced a strong movement in our concept of painting. We in it ... saw the image of objects not similar, but

accurate, alive; not painted from nature, but depicting nature itself ... Some Artists assured that in the Granet painting, focal lighting is the cause of this charm, and that with full light, directly illuminating, it is in no way possible to produce this striking animation of objects, neither animated nor material. I decided to conquer the impossible ... To succeed in this, I needed to be completely

leave all the rules and manners to portray nothing

otherwise than it is in nature, and obey it alone, without

admixtures of the manner of some artist ... ". From these words, it is easy to see that Venetsianov was carried away by the desire not to imitate this picture, but to surpass it. He decided to convey the space in normal lighting conditions, without applying the effect of strong light.

In the painting “The Barn”, the barn depicted from the inside is illuminated with an even, calm, diffused light. The view of the viewer from the figures of peasants sitting in the foreground follows further. This is facilitated by the rhythm of the logs going into the depths. Each segment of the distance is marked by the artist, at first glance, with insignificant, but very important details for conveying the perspective: a broom and a rake in the foreground, a figure of a man, a pile of grain and a horse in the center, a cart in the depth, etc. The artist accurately and ingenuously follows nature, he is attentive to all its manifestations. The peasants in his picture are posing, and Venetsianov does not hide this. They dressed up on purpose, the women wore elegant sundresses, white sweaters, the men wore pure Armenians. Despite the stiffness of the movements, they retain life-like plausibility. Venetsianov does not yet connect the figures with a single action or plot. The main thing for him is to correctly portray nature. Venetsianov knows how to find a special charm in everyday objects of peasant life. He lovingly and carefully conveys the interior space of the threshing floor. The first plan is lit with even light, then - where the lighting is; should fade, a stream of daylight bursts in from the street through the open door on the left; in the depths - again a bright light. The transitions from the illuminated areas of the plank floor to the dark ones are very gradual. The shadows in the picture are transparent - this is the result of the artist's subtle observations in nature. Work on the painting "Barn" became a real school for Venetsianov. But the artist continued to persistently improve his skills.

Simultaneously with this canvas, Venetsianov executed the painting “Cleaning the Beets” in the pastel technique. Here, for the first time, the artist unites the characters with a single action and mood. Bringing figures to the fore, he seeks to convey the state of mind of his characters. The composition is natural, the poses of the peasants are observed in reality itself. The nobility of the color solution enhances the expressiveness of the picture.

The program work of these years was the painting "Morning of the landowner", depicting an everyday scene from the life of the landowner's estate. The characters on this canvas live naturally and freely in space. The face of the landowner, her look, her gesture are turned to the peasant woman squatting down, holding the yarn. The standing peasant woman turned her face towards the viewer, as if urging him to be a witness to this scene. Silence, cosiness, peace emanates from this work, in which the artist captured his wife Marfa Afanasievna and serfs from his small estate. Depicting peasant women, Venetsianov emphasizes their beauty and calm dignity. He treats them with no less respect than the landowner. The whole scene is solved convincingly and in a special authentic way, because the artist knew this life to the smallest detail with all its furnishings: a simple pine screen, a small mahogany table, figurines on a chest of drawers in a dark corner, green curtains on the window. Venetsianov subtly developed the characterization of lighting in the interior, where contrasts of light and shadow coexist with soft, barely noticeable transitions, which allowed the artist to fill the picture with a sense of real life.

In the painting of the same period "Reapers" ( Appendix 5) Venetsianov gives the actors a close-up, brings them closer to the viewer. The tired, ugly face of a peasant woman attracts with high humanity, life-like veracity of the image. Next to her is a bright boy with a tanned, broad-cheeked face, with an inquisitive look. He froze, admiring the color of the butterfly's wings. A deep understanding of the beautiful is available to the peasants, this is what Venetsianov draws the viewer's attention to. The composition of this canvas is distinguished by seriousness and thoughtfulness. Its content is revealed in clear and expressive forms. In the upper left and in the lower right, the artist places sickles, which, as it were, close the composition, giving it stability and balance. The turn of the peasant woman's head and the boy's gaze fixed on her hand bind them together. Dense colors contribute to the creation of a rich artistic image. We feel both the heavy heat of a summer day, and the immensity of a field standing like a wall, and the sense of belonging to the beauty of the earth and spiritual closeness that has gripped people.

One of the best works of Venetsianov is the painting “In the Harvest. Summer ”(1830s), in which there are more everyday characteristics ( Appendix 6). However, the poetic vision of the world in it is also decisive. Here, Venetsianov perfectly conveys the feeling of a hot summer day, when the sun is still high in the sky, but soon it will slowly begin to decline. Hot, warm earth. Fields with ripe, partially already stacked sheaves alternate with uncut strips of rye, then there is a horizontal field covered with grass, and then again fields.

Much brings this canvas together with the simultaneously written “On arable land. Spring". And this is, first of all, the image as main topic season, and not abstractly, not through the introduction of allegories, as was typical of academic art, but through the display of field work with the inclusion of figures of working and resting peasants. Of course, this show is not yet perfect: the theme of hard peasant labor, in essence, is bypassed by the artist. The heroes of these paintings, which have a light, lyrical sound, are real Russian peasants contemporary to the artist.

In the canvas “In the harvest. Summer ”Venetsianov depicts a peasant woman at the moment of a short break from work. Her appearance is free from that touch of idealization that took place in the previous work.

The picture "Summer" sounds more monumental. Her composition is unique: a female figure painted on a large scale stands out in the foreground, followed by a landscape, the composition of which is built on horizontal lines. The figure of a woman sitting on a platform seems frozen. Next to her, on the empty surface of the platform, lies a sickle - a constant Venetian attribute of field work.

I. Dorogonevskaya notes that in some of Venetsianov's works, the portrait and everyday genre are closely related to each other. She writes: “In essence, the artist continues here his line of calmly descriptive genre painting, but in somewhat different forms. He creates original portraits-pictures in which the image of a person is revealed in his activity, which enhances his typical features.

Most of all, the master was more interested in revealing characters than in the plot itself. Thus, in the paintings “A Girl with a Beetroot” (circa 1824), “Reapers” (1825) and others, first of all, the human dignity of the Russian peasant, his moral purity, and great spiritual wealth are shown.

One of the finest works of the artist, Peasant Woman with Cornflowers (1830s), belongs to the Venetian type of genre portraits. The breadth of the pictorial scope of nature, the courage and confidence of writing here are amazing. With deep attention and penetration, the quivering spiritual world of a Russian woman is conveyed in the picture.

A large place in the work of Venetsianov was occupied by images of children. Vital immediacy marked the images of village children in the paintings "Peasant Children in the Field" and "Peasant Boy Putting on Bast Shoes". The artist captures his young heroes sometimes among the expanses of fields, sometimes in the atmosphere of a poor hut. He treats children's characters with amazing seriousness and respect.

Thus, the ancestor of the Russian everyday genre was by no means an ordinary writer of everyday life. He was an artist-poet who was extremely sensitive to, acutely felt poetry and beauty in the life of people and nature.

As we have already noted, some researchers of Venetsianov's work reproached the artist for idealizing peasant images, for not showing the hardships of peasant labor. In these cases, it is useful to recall a number of historically determined reasons that the artist at that time could not cross. It is much more important for us to correctly assess the contribution of Venetsianov to Russian painting, to determine the nature of his innovation.

As he notes, “Venetsianov was one of the first in Russian painting of the 19th century who approved the right of a enslaved person to be depicted in art, discovered in his existence a high spirituality and moral strength.”

From the end of the 40s of the 19th century, female artists began to openly expose the vices of contemporary society. realism came to replace academic art. Pavel Andreevich Fedotov (1815-1852), whose works are literally imbued with the spirit of satire, laid the features of a new direction - critical realism - in the everyday genre. What all the artists of the previous generation and his closest contemporaries lacked - the depth of comprehension of everyday life, its dramatic essence, its social conflicts - all this is the content of Fedotov's work. Fedotov, in the words of Belinsky, had a "faithful outlook on life", and this view is openly expressed in all his works.

The main thing in the work of Fedotov was everyday painting. notes: “Even when he paints portraits, it is easy to detect genre elements in them (for example, in the watercolor portrait “Players”). His evolution in genre painting - from the caricature to the tragic, from overloading in details, as in "The Fresh Cavalier" (1846), where everything is "described": a guitar, bottles, a mocking maid, even papillots on the head of an unlucky hero, - to the ultimate laconicism, as in "The Widow" (1851), to the tragic sense of the meaninglessness of existence, as in his last painting "Anchor, more anchor!" (1851 - 1852). The same evolution in the understanding of color: from color that sounds half-hearted, through pure, bright, intense, saturated colors, as in the "Major's Courtship" (1848) or "Aristocrat's Breakfast", to the exquisite color scheme of "The Widow", conveying the objective world as if dissolving in the diffused light of the day, and the integrity of the single tone of his last canvas (“Anchor ...”). It was a path from simple life writing to implementation in clear, restrained images. critical issues Russian life, for what, for example, is the "Major's Matchmaking" if not a denunciation of one of the social facts of the life of his time - the marriages of impoverished nobles with merchant "money bags"? And "The Picky Bride", written on the plot, borrowed from (very, by the way, appreciated the artist), if not a satire on marriage of convenience? Or is it a denunciation of the emptiness of a secular dude who throws dust in his eyes - in the "Breakfast of an Aristocrat"?

The first significant work of Fedotov is the painting "The Fresh Cavalier, or Morning of the official who received the first cross" ( Appendix 7). The picture is written in great detail, with unflagging attention to every subject. The action takes place in a cramped and dark room. The canvas depicts a clerk who celebrated the night before with a stormy feast when he was awarded the Order of Stanislav III degree (by the way, the lowest of the orders Russian empire) and now unconditionally boasting in front of a concubine, a cheeky maid. The latter, in response to bravado, mockingly holds out a holey boot - is the master not going to repair his worn-out shoes with the silver of a trinket fastened on?

writes: “Fedotov’s satire, like Gogol’s satire, goes much further than the image of a vulgar braggart and his pretty cook. The comic case acquires a great generalizing meaning in the interpretation of Fedotov, the image of the “fresh gentleman” becomes a satirical image. "Fresh Cavalier" is the apogee of human emptiness, swagger and vulgarity. Life itself has formed this type. The whole atmosphere of the bureaucratic service, with its cringing and inflated arrogance, was imprinted on him with extreme distinctness. The pose of the “fresh gentleman” is a parody of the greatness of ancient statues: a bare foot put forward, a dressing gown like a toga, a proud gesture, an arrogant look. To match the hero and the backstage hostess of this dirty nest, in which both of them feel quite comfortable.

The second, the main one for Fedotov, is his painting “Major's Courtship” (1848), which recreates an episode from a merchant's life. for this work the artist received the title of academician ( Appendix 8). At the door of the living room of the former mansion acquired by the merchant, the future nobleman-in-law finally appears.

The content of events is instantly guessed by the viewer. Having barely glanced at the canvas, he stops at the light silhouette of the figure of the merchant's daughter, looming against the general muted dark background of the room. Her attempt to sneak into the next room is immediately recognized as coquetry. Since the behavior of the bride is understandable at first glance, the viewer moves from the center to the second element of the composition highlighted by lighting - the doorway, flooded with light from the front, in which the figure of the major darkens.

The brave soldier with his proud posture looks like a creature of a different, “higher” order in relation to the merchant world. But the "nobility of origin" does not at all prevent him from accepting the laws of the chistogan put forward by the new social stratum, when everything and everything is declared a commodity. For the major, his title serves as a commodity, and for the merchant, the dowry of his daughter. With all the outward arrogance, the major does not leave the merchant's "dark" kingdom, but enters it. This is emphasized by the coloristic interconnection between the figures of the bride and groom (the light pink spot of the dress is decoratively combined with the green color of the front wall and the dark green uniform, because with external contrast they make up the so-called complementary tones in relation to each other). That is why the viewer's gaze from the figure of the major again returns to the merchant's daughter - to the center. The color interrelation of pink tones in the girl's dress and lilac tints in the mother's dress makes one look more closely at the merchant's wife who grabbed her daughter by the skirt. The elegance of her clothes does not hide the straightforwardness of her nature (you can see from the rounded outlines of her mouth that she screams: “Fool!”). Primitive straightforwardness finds itself in the head of the family. Blurring in an obsequious, contented smile, he hurries to meet the long-awaited guest.

This picture continues the critical line that determined Fedotov's talent. If the appearance of the characters of the first work was caricatured in order, as it seemed to the master, to highlight the idea more sharply (this applies not only to the image of the gentleman, but also to the cook, with her glossy, greased, unpleasant face, stealthily shifting eyes, with clothes swollen on her stomach ), then the main characters of the second picture even look cute. The major bribes with youth, bearing, preserved despite his age. Op is a real “military bone”. The bride is simply beautiful. Here, negative assessments are given not to individuals, but to life rules environment. Negative conclusions come to the viewer not as a result of something directly perceived, but as a fruit of reflection, their result.

Another social stratum is represented by the painting "The Picky Bride" ( Appendix 9). With great force, Fedotov characterizes the characters. What merciless strokes the image of an old maid is given! An expression of languid delight is written on her face. The hunchbacked groom, dressed in all the luxury of fashion, with great difficulty knelt before her, presenting a bouquet of flowers. He has the old face of a satyr. He is all shiny and glossy, starting with a pink bald head framed by fixed hair, and ending with polished fashionable boots. The rich living room is furnished in the latest fashion. Joyfully excited parents look out from behind the curtains, they give thanks to the sky, raising their eyes to the ceiling. This is a satire on the form of marriage that was accepted in the "light". This is a marriage without the poetry of feeling, without love - this is a deal. There is no romance in these withered, hardened souls.

The ostentatious life of a secular dandy was depicted by the artist in "Breakfast of an Aristocrat" ( Annex 10). With all his might, Fedotov's character disguises himself as a rich aristocrat, but in fact he eats black bread, a piece of which he hastily swallows, having heard the steps of an unexpected guest.

One of the most poetic works of Fedotov is the one-figure composition "The Widow" ( Annex 11), which became the embodiment of the artist's longing for the sublime, beautiful and humane in life.

A widow is an unforgettable image of a suffering woman. Her whole previous way of life collapsed catastrophically. She is threatened by poverty and hunger. It is impossible and unfair to see in this picture of Fedotov some kind of sentimental plaintive scene. Life is shown here on the sharp edge of the past and the future.

One of the last works of the artist is the unfinished painting "Anchor, more anchor!" ( Annex 12). Unlike all previous canvases, this small picture lacks a detailed action. Taking as a basis the simplest and most uncomplicated plot, retaining elements of the funny only in the title (the repetition of the same word in Russian and French), Fedotov raises a meaningless motif to a highly generalized image.

The artist depicted a young officer who spends evening after evening in a stupefying boredom. The mood of loneliness is created by light and masterfully selected colors. Among the golden-brown darkness of a small room, a red tablecloth stands out as a bright spot. A candle flame flickers on the table, and immediately behind it, through a small window, a street is visible on a winter night - pure snow sparkling in the moonlight, frost and silence. The opposition of bluish and red shades emphasizes the sharp tragic contrast between the officer killing his time and the world indifferent to his fate.

The idea of the eventlessness of this being is, as it were, spilled over the whole picture, entered into its flesh and blood, grew, became a symbol. This is a symbol of suffocation, longing, hopelessness, languor of the soul - a symbol of a terrible life.

According to the thought, “Anchor, another anchor!” “Imbued with the idea of autobiography. This does not mean that the artist depicts himself as the main character (which, by the way, he often did in his works). The picture is filled with that feeling of mortal anguish that the artist was overwhelmed with on the eve of death. Here the evolution of the artist was bound to end, his life was to be cut short.

The art of Fedotov as a genre painter completes the development of painting in the first half of the 19th century, and at the same time, quite organically - thanks to its social sharpness - the "Fedotov direction" opens the beginning of a new stage - the art of critical realism.

It was the Wanderers, whose progressive art was an expression of democratic ideas in Russian art of the second half of the 19th century, that continued the work and traditions. household genre in the best works Wanderers is devoid of any anecdotal. The social orientation and high citizenship of the idea distinguish it in European genre painting of the 19th century.

Wanderers - members of the Association of Travelers art exhibitions, which was founded in 1870, began a new stage in the development of realistic painting. The everyday genre, leading in their work, receives an organic social sound.

A major phenomenon in the development of the Russian national school of painting was the painting "Barge Haulers" (1870 - 1873), in which the young artist, with all the power of talent, gave an exciting image of an oppressed, but not crushable people in its strength. “Mr. Repin is a realist, like Gogol, and as much as he is deeply national,” wrote Stasov. the whole depth of people's life, people's interests, people's pressing reality. Just take a look at Mr. Repin's Barge Haulers, and you will immediately be forced to admit that no one has ever dared to take such a plot from us and that you have not yet seen such a deeply amazing picture of Russian folk life ... According to plan and expression of his painting, Mr. Repin is a significant, powerful artist and thinker, but at the same time he owns the means of his art with such strength, beauty and perfection as hardly any other Russian artist.”

One of the central places in the painting of the Wanderers was occupied by the peasant theme, and this is quite natural, because all the fundamental issues of the post-reform development of society in the 70s and 80s concerned mainly the sphere of peasant life.

Particularly important for the solution of the peasant theme in the painting of the Wanderers was the painting “Zemstvo is having lunch” (1872), shown on the 2nd traveling exhibition. In this seemingly ordinary everyday plot, the artist-democrat without embellishment depicted contemporary reality, convincingly showed that the participation of peasants in local self-government, about which government bodies made so much noise after the reform of 1861, is only fiction, deceit and hypocrisy. A significant advantage of this picture is the special attention that the artist pays internal characteristic peasants, the ability to create expressive types, such as, for example, the image of a peasant sitting on the steps of a porch. In his concentrated pose with his head down, in the courageous features of his face, a deep thought is read, a desire to comprehend what is happening.

The Wanderer was an artist who devoted his talent entirely to the peasant theme. Maksimov's largest painting, The Coming of a Sorcerer to a Peasant Wedding (1875), attracts not only with a deep knowledge of the village, but also with great love for its people. The main thing in this work, executed with outstanding compositional and pictorial skill, is the desire to reveal the charm of folk images, to show the peculiar poetry of peasant life.

Already in the very title of this picture there was something unusual, poetic and almost fabulous. The arrival of the sorcerer! Meanwhile, everything is absolutely real. FROM full knowledge cases, Maximov convincingly described a peasant wedding in a Russian village of the 19th century, and a festively decorated hut, and dressed up guests. Here and sedate people, and brisk youth. Each has its own character, and the image of each is individual, psychological.

Among all these people, the sorcerer - a powerful old man with an unkind face and a wary look - is the same person and as real as everyone else. Meanwhile, the sorcerer is a living embodiment of distant pagan rites preserved in the patriarchal village. As in peasant life itself, where naive superstitions and sober rationality coexist, so in the picture the appearance of a sorcerer, and the anxiety of relatives who are afraid of the "evil eye", and their curiosity, and the feigned indifference of the deacon who "does not notice" the sorcerer, etc. At the same time, there is something very poetic about this patriarchal village, with its folk art and semi-pagan rites. So entered Russian painting new topic associated with the poetic side of folk life.

The most diverse aspects of the bleak peasant life were also vividly reflected in the work of Maksimov (“Family Section”, 1876; “Sick Husband”, 1881, etc.).

In 1878, at the 6th Traveling Exhibition, he showed the painting "Meeting the Icon" (1878). The depicted moment, typical for the village, made it possible for the artist to develop a whole gallery of characteristic images, to convey a diverse range of feelings and experiences. The plot of the picture is built on a contrasting juxtaposition. On the one hand, there is a sincere feeling, a naive faith of the dark, impoverished peasant masses in a miraculous icon, on the other hand, representatives of the clergy are completely indifferent to everything that happens. A large emotional role in the picture is played by the nondescript landscape of the village outskirts. A gray, overcast autumn day largely determined the muffled darkish-silver coloring of the picture.

One of the best itinerant artists is rightfully considered (1833 - 1882), who already by the time of the organization of traveling friendly exhibitions had developed as an amazing master, most of whose works had a social connotation.

In his work, Perov undoubtedly used the traditions of Fedotov, but at the same time he went further than his predecessor and dared to touch on topics that Fedotov did not even dare to dream of. At the beginning of his creative way Perov, with ruthless criticism, turned on the life and customs of the Russian clergy.

The central picture of this circle is the "Rural procession on Easter" ( Annex 13), which was written in 1861. The content and figurative structure of this canvas became truly innovative. The priest, who is barely on his feet, disrespectfully clutched the cross in his hand. On the porch stretched out a dead drunk clerk with a censer. A peasant dressed in rags carries an inverted icon. The picture exposes the squalor of life and the darkness of the Russian village of that time.

One of the significant works of Russian realistic painting is Perov's painting "Seeing the Dead" ( Annex 14), written in 1865. Simple in content, it is filled with deep social meaning.

"Seeing the Dead" takes the viewer to the Russian village, and one of the greatest tragedies in the life of a peasant family is revealed to him - the death of the breadwinner. A funeral… Instead of a charioteer, a young widow sits on the irradiation, head down, bent over, and in the sleigh, clinging to the coffin, two children froze motionless. The whole canvas is permeated with the mood of sorrow and loneliness. The horse, as if feeling the grief of the owners, slowly and heavily steps up the mountain. Even nature silently froze, the fastened forest froze, winter clouds hung heavy.

The bluish tone of the snow-covered space and the evening sky, the wood with a coffin and an orphaned family evoke a feeling of homelessness and longing. The light lemon stripe of a winter sunset under the approaching night clouds, which contrasts with the surrounding bluish tones with its color, enhances the emotional impact of the cold range. Solid yellow-brown colors (yellow coffin, yellow-brown sheepskin coats, a bay horse), uniting the depicted group in a color scheme, also silently speak of the loneliness of the captured people, left only to themselves in life.

Researchers naturally associate "Seeing the Dead Man" with the poem "Frost, Red Nose", which was published in 1863. It is known that Perov was a passionate admirer of this poet.

In 1868, Perov created one of his best paintings - "The Last Tavern at the Outpost" ( Annex 15), characterized by a great emotionality of the artistic image. Here the story is extremely laconic, but the picture deeply excites, evokes a chain of associations, echoes Russian poetry. The lonely figure of a peasant woman in a sleigh seems to be the embodiment of hopeless patience. Bluish-gray snow, dark silhouettes of houses with reddish-yellow stains of windows, a cold, poignant, lemon-yellow sunset line near the horizon, against which the silhouettes of the outpost blacken, a single tonal color - warmer in the foreground, as if retaining a particle of heat from residential houses, and cold on the second - give the picture wholeness and emotionality, cause a feeling of anxiety and grief.

The picture was painted in a manner not previously characteristic of Perov. Purity of color and lightness of writing are its distinctive pictorial features. The free brushstroke enhances the feeling of a piercing wind that covers the sledges, doors and windows of houses with snow, ruffles the horses' manes. The emotionality of the landscape is a means of interpreting the event and human experiences. This is extremely characteristic not only of the best works of Perov, but also of a number of works by Russian poets and artists of that time.

The attractive power of the genre works of the Wanderers lay in the novelty of not only the plots themselves, but also in the unusually accessible form of a detailed pictorial narrative, which vividly echoed progressive literature and dramaturgy. It was a new ideological and aesthetic content of art, directly reflecting life, full of deep humanity and noble thoughts, strikingly opposed to cold academic canvases on abstract topics.

The success of the works of genre painters was also associated with the high professional skill of performance. Their paintings testify to the artists' excellent knowledge of nature, the ability to convey an acute social situation, and to describe the state of mind of the person depicted. A wide range of discreet tonal relationships in painting, free and accurate drawing, careful development of the necessary details of the composition are characteristic of most of the genre paintings of the Wanderers. Everything was directed towards one goal: to convey content to the viewer, to make them empathize, love or hate.

The work of the Wanderers completed the formation of the everyday genre in Russian fine arts. Thanks to their innovation, the everyday genre has taken a leading place among other genres of Russian fine art. Since the time of their work, the combination of acutely perceived characteristic features everyday life with generalization, emotional richness, full of symbolism of images and situations that directly express likes and dislikes, attitude and social views of the artist.

LIST OF USED LITERATURE:

1. Batazhkova Gavrilovich Venetsianov. - L .: Artist of the RSFSR, 1966. - 52 p.

2. Dorogonevskaya Gavrilovich Venetsianov. // Alexei Venetsianov. Album. - M .: Fine Arts, 1969. - S. 2 - 8.

3. Ilyina arts. Russian and Soviet art. – M.: graduate School, 1989. - 400 p.

4. History of Russian art. / Ed. and. - M.: Visual arts, 1987. - 400 p.

5. History of Russian art. In 2 vols. T. 2. Book. 1. / Ed. . - M.: Visual arts, 1980. - 312 p.

6. Kon'kov history of painting. – M.: Veche, 2002. – 512p.

7. Krasnobaev of the history of Russian culture of the XVIII century. – M.: Enlightenment, 1987. – 319 p.

8. Kuznetsova. // Venetsianov. Image and color. Album. - M .: Fine Arts, 1976. - S. 4 - 5.

9. From Russian history artistic culture. Studies, essays, articles. - M .: Soviet artist, 1982. - S. 132 - 142.

10. Essays on the history of Russian culture in the second half of the 19th century. - M.: Enlightenment, 1973. - 430 p.

11. Paramonov. // Wanderers. Album. - M.: Art, 1976. - S. 5 - 22.

12. Pikulev fine arts. - M.: Enlightenment, 1977. - 288 p.

13. Sarabyanov. // Fedotov. Image and color. - M.: Visual arts, 1978. - S. 4 - 5.

14. Dictionary of art history terms. - M.: Art, 1997. - 351 p.

Dictionary of art history terms. - M.: Art, 1997. - S. 35.

Krasnobaev of the history of Russian culture of the XVIII century. - M .: Education, 1987. - S. 216.

Konkov history of painting. - M.: Veche, 2002. - S. 186.

Cit. Quoted from: Konkova history of painting. - M.: Veche, 2002. - S. 253.

Cit. by: Kuznetsova. – M.: Visual arts, 1976. – P. 4.

Dorogonevskaya Gavrilovich Venetsianov. – M.: Visual arts, 1969. – P. 6.

Kuznetsova. – M.: Visual arts, 1976. – P. 5.

Ilyin Arts. Russian and Soviet art. - M .: Higher School, 1989. - S. 195 - 196.

From the history of Russian artistic culture. Studies, essays, articles. - M .: Soviet artist, 1982. - S. 137 - 138.

Sarabyanov. – M.: Visual arts, 1978. – P. 5.

Cit. by: Paramonov. – M.: Art, 1976. – P. 9.

Dedicated to everyday private and public life (usually contemporary artist). Everyday ("genre") scenes, known in art since ancient times, stood out as a special genre in the feudal era (in countries Far East) and during the formation of bourgeois society (in Europe). The heyday of the everyday genre of modern times is associated with the growth of democratic and realistic artistic trends, with the appeal of artists to the depiction of labor and folk life. Images on everyday topics were already present in primitive art(scenes of hunting, processions), in ancient oriental paintings and reliefs (images of the life of kings, nobles, artisans, farmers), in ancient Greek vase painting and reliefs, where they were often included in mythical compositions or scenes afterlife. They occupied a significant place in Hellenistic and ancient Roman art (paintings, mosaics, sculpture). In the medieval art of Europe and Asia, genre scenes were often woven into religious and allegorical compositions (paintings, reliefs and miniatures). From the 4th century genre painting of the Far East (China, later Korea, Japan) developed.

In the everyday genre of Russian critical realism, the exposure of the feudal way of life and sympathy for the disadvantaged were complemented by a deep and accurate penetration into the spiritual world of the characters, a detailed narrative, and a detailed dramatic development of the plot. These features, clearly manifested in the middle of the XIX century. in the paintings of P. A. Fedotov, full of burning mockery and pain, in the drawings of A. A. Agin and T. G. Shevchenko, were perceived in the 1860s. genre-democrats - V. G. Perov, P. M. Shmelkov, who combined direct and sharp journalism with a deep lyrical experience of the life tragedies of the peasantry and the urban poor. On this basis, the everyday genre of the Wanderers grew up, which played a leading role in their art, which exclusively fully and accurately reflected folk life the second half of the 19th century, which intensively comprehended its social patterns. A detailed picture of the life of all strata of Russian society was given by G. G. Myasoedov, V. M. Maksimov, K. A. Savitsky, V. E. Makovsky, and - with special depth and scope - I. E. Repin, who showed not only barbarian oppression of the people, but also the fighters for its liberation, the mighty vitality hidden in the people. Such a breadth of the tasks of the genre picture often brought it closer to the historical composition. In the paintings of N. A. Yaroshenko, N. A. Kasatkin, S. V. Ivanov, A. E. Arkhipov in late XIX- early XX centuries. reflected the stratification of the countryside, the life of the working class. the everyday genre of the Wanderers found a wide response in the art of Ukraine (N. K. Pimonenko, K. K. Kostandi), Belarus (Yu. M. Pen), Latvia (Y. M. Rozental, Y. T. Valter), Georgia (G I. Gabashvili, A. R. Mrevlishvili), Armenia (E. M. Tatevosyan) and others. The successes of democratic realism in the everyday genre of the 19th century. were associated with the formation and rise of the artistic culture of many peoples in the course of their struggle for national and social liberation (M. Munkacsy in Hungary, K. Purkin in the Czech Republic, A. and M. Gerymsky and Y. Chelmonsky in Poland, N. Grigorescu in Romania , I. Myrkvichka in Bulgaria, D. Skutetsky in Slovakia, J. F. de Almeida Junior in Brazil, L. Romagnach in Cuba). Genre-everyday features are also shown in the portrait landscape, historical and battle painting. At the same time, the everyday genre is sometimes imbued with religious-patriarchal or bourgeois morality, idyllic or entertaining features. A weakening of socially critical tendencies marked the work of a number of major genre painters (J. Bastien-Lepage, L. Lermitte in France, L. Knaus, B. Vautier in Germany, K. E. Makovsky in Russia). Artists associated with Impressionism (E. Manet, E. Degas, O. Renoir in France), in the 1860s-80s claimed a new type of genre painting, in which they sought to capture, as it were, a random, fragmentary aspect of life, an acute characteristic of the appearance of characters, the unity of people and their environment natural environment. These trends gave impetus to a freer interpretation of the everyday genre, a direct pictorial perception of everyday scenes (M. Lieberman in Germany, E. Werenschell, K. Krogh in Norway, A. Zorn, E. Yousefson in Sweden, W. Sickert in Great Britain, T. Aikins in the USA, V. A. Serov, F. A. Malyavin, K. F. Yuon in Russia).

At the turn of the XIX-XX centuries. in the art of symbolism and the "modern" style, there is a break with the tradition of the everyday genre of the 19th century. Everyday scenes are treated as timeless symbols; the vital concreteness of the image gives way to monumental and decorative tasks (E. Munch in Norway, F. Hodler in Switzerland, P. Gauguin in France, V. E. Borisov-Musatov in Russia).

Traditions of realistic everyday genre of the 19th century. were picked up in the 20th century. artists who sought to reveal the contradictions of capitalism, to show resilience, inner strength and the spiritual beauty of people from the people (T. Steinlen in France, F. Brangvin in Great Britain, K. Kollwitz in Germany, D. Rivera in Mexico, J. Bellows in the USA, F. Maserel in Belgium, D. Derkovich in Hungary, N Balkan in Bulgaria, S. Lukyan in Romania, M. Galand in Slovakia, etc.). After the Second World War of 1939-45, this direction was continued by the masters of neorealism - R. Guttuso, A. Pizzinato and others in Italy, A. Fougeron and B. Taslitsky in France, Ueno Makoto in Japan. A characteristic feature of the everyday genre was the combination of acutely perceived characteristic features of everyday life with generalization, often symbolism of images and situations. In the liberated and developing countries of Asia and Africa, original schools of national everyday genre have developed, rising from imitation and stylization to a deep generalized reflection of the way of life of their peoples (A. Sher-Gil, K. K. Hebbar in India, K. Affandi in Indonesia, M Sabri in Iraq, A. Tekle in Ethiopia, sculptors Kofi Antubam in Ghana, F. Idubor in Nigeria). Artists of modernist movements - pop art and hyperrealism - sometimes turn to everyday scenes, but their works do not go beyond passive fixation taken out of context. real life fragments of reality.

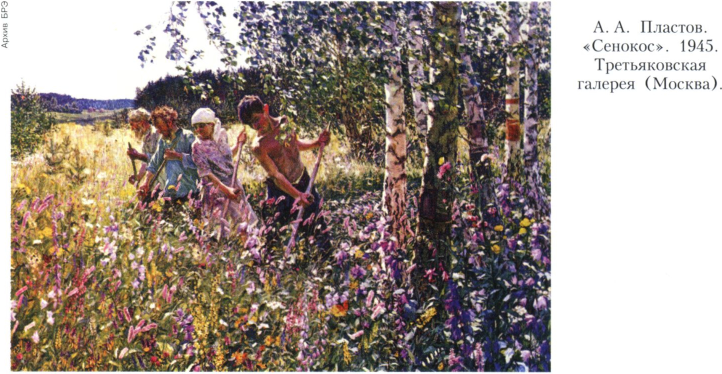

After the October Revolution of 1917, the everyday genre acquired in Soviet Russia new features, conditioned by the formation and development of socialist society, are historical optimism, the assertion of selfless free labor and a new way of life based on the unity of social and personal principles. This unity gave rise to a close connection between the everyday genre and the historical genre, which are often intertwined. The everyday genre played an important role in the development Soviet art reflecting the building of socialism and communism, the formation of the spiritual world of the Soviet people in many ways. From the first years of Soviet power, artists (B. M. Kustodiev, I. A. Vladimirov) sought to capture the changes brought by the revolution to the life of the country. In the 20s. the AHRR association arranged a number of exhibitions dedicated to Soviet life, and its masters (E. M. Cheptsov, G. G. Ryazhsky, A. V. Moravov, B. V. Ioganson) created a number of reliable typical images showing new relationships between people. The artists of the OST association (A. A. Deineka, Yu. I. Pimenov) created a special type of paintings dedicated to construction, labor, and sports, in which they generally expressed new features of the appearance and life of Soviet people; poetic paintings of traditional and new life were performed by P. V. Kuznetsov, M. S. Saryan, P. P. Konchalovsky, K. S. Petrov-Vodkin. Household genre of the 30s. affirmed a joyful, festive perception of life (S. V. Gerasimov, A. A. Plastov, T. G. Gaponenko, V. G. Odintsov, F. G. Krichevsky). In the Soviet household genre reflected hard life front and rear during the Great Patriotic War 1941-45 (Yu. M. Neprintsev, B. M. Nemensky, A. I. Laktionov, V. N. Kostetsky, A. F. Pakhomov, L. V. Soyfertis), enthusiasm for collective work and social life, typical features everyday life in the postwar years (T. N. Yablonskaya, S. A. Chuikov, F. P. Reshetnikov, S. A. Grigoriev, U. M. Dzhaparidze, E. F. Kalnyn, L. A. Ilyina). Since the second half of the 50s. in the paintings of G. M. Korzhev, V. I. Ivanov, E. E. Moiseenko, V. E. Popkov, T. T. Salakhov, D. D. Zhilinsky, E. K. Iltner, I. A. Zarin, I. N. Klycheva, N. I. Andronov, A. P. and S. P. Tkachevs, T. R. Mirzashvili, S. M. Muradyan, engravings by G. F. Zakharov, V. M. Yurkunas, V V. Tolly everyday life of the people appears rich and complex, saturated with great thoughts and experiences. Works of household genre of the 60-80s. often serve to express deep philosophical thoughts about life.

An important contribution to the development of the realistic everyday genre was made by the artists of the socialist countries, who vividly reflected the formation of new social relations in the life of their peoples, showing the characteristic features of national life (K. Baba in Romania, S. Venev in Bulgaria, V. Vomaka in the GDR, M. Benka , L. Fulla in Czechoslovakia, Nguyen Duc Nung in Vietnam, Kim Yongjun in the DPRK, Jiang Zhaohe in the PRC).

Lit .: N. Apraksina, Household painting, L., 1959; B. M. Nikiforov, Genre painting, M., 1961; Russian genre painting XIX in. [Album of reproductions, M., 1961]; Russian genre painting of the 19th - early 20th centuries, M., 1964; [E. J. Fechner], Dutch genre painting of the 17th century. in the State Hermitage, Moscow, 1979; Brieger L., Das Genrebild. Eine Entwicklung der bürgerlichen Malerei, Münch., ; Hütt W., Das Genrebild, Dresden, .

HOUSEHOLD GENRE -

A genre of fine art dealing with daily private and public life (usually by a contemporary artist).

Images on everyday topics were already present in primitive art (scenes of hunting, processions), in oriental paintings and reliefs (images of the life of kings, nobles, farmers). They occupied a significant place in Hellenistic and ancient Roman art (in vase painting, reliefs, murals, mosaics, and sculpture).

From the 4th century genre painting of the Far East (China, Korea, Japan) developed.

In the medieval art of Europe, genre scenes were often woven into religious and allegorical compositions (paintings, reliefs, miniatures).

HOUSEHOLD GENRE. Renaissance. Netherlands (Flanders). Eick, Jan Wang.

Marriage of Arnolfini.

Wedding ceremony of Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife Giovanna Genami

During the Renaissance, religious and allegorical scenes in painting began to take on the character of a story about a real event, saturated with everyday details (Giotto, A. Lorenzetti, Jan van Eyck, R. Kampen, Gertgen tot Sint-Jans), images of human labor activity appeared (Limburg, Schongauer, Kosee).

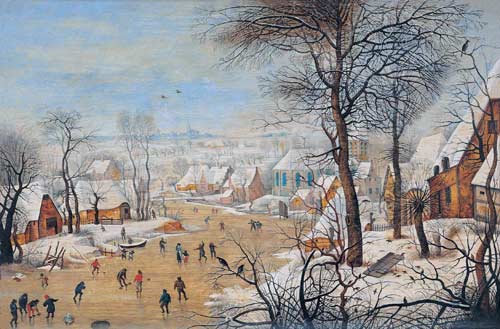

At the end of the XV - beginning of the XVI century. in the work of a number of artists, the everyday genre gradually began to stand apart (V. Carpaccio, Giorgione, J. Bassano, C. Masseys, Luke Leydensky). In the works of P. Brueghel and J. Callot, the depiction of pictures of everyday life has become a way of expressing relevant social and philosophical ideas (ideas of social justice, non-violence, etc.).

HOUSEHOLD GENRE. Netherlands.

Brueghel the Younger, Pieter. Winter landscape with bird trap

in different national schools 17th century formed different kinds everyday genre, often asserted in the fight against idealizing tendencies.

So, in the work of Caravaggio in Italy, which influenced the development of realism in European art of the 17th century. emphatically truthful, monumental depiction of the scenes of life of the lower classes in religious compositions was opposed to the idealizing principles of academism.

The sublime poetization of everyday motifs included in mythological and allegorical compositions, the assertion of the mighty vital forces contained in the people are characteristic of the works of P. P. Rubens and J. Jordaens in Flanders, which polemize with the principles of the official Baroque.

The household genre occupied the leading position in Holland, where its classical forms finally took shape.

The poeticization of peasant and burgher life with its inherent intimate atmosphere of peaceful comfort is characteristic of A. van Ostade, K. Fabricius, P. de Joch, J. Vermeer of Delft, G. Terborch, G. Metsu.

In the second half of the XVII - early XVIII century. there has been a discrepancy between the democratic direction in the everyday genre (the works of Rembrandt, A. Brauer, S. Rosa and J. M. Crespi) and the idealizing art of everyday life (D. Teniers, K. Netscher in Holland).

In contrast to the idyllic pastorals and “gallant scenes” of Rococo art (F. Boucher), a family genre and everyday satire arise (W. Hogarth, A. Watteau and J. O. Fragonard, J. B. S. Chardin; J. B. Greuze ).

Realistic tendencies appear in everyday paintings artists of Italy (P. Longi), Germany (D. Khodovetsky), Sweden (P. Hilleström), Poland (Ya. P. Norblin).

Cheerful democracy, poetic brilliance in the perception of the world are imbued with early works on everyday topics by the Spaniard F. Goya.

In Russia, the household genre developed from the second half of the 18th century. (I. Firsov, M. Shibanov, I. Ermenev).

In the XVI-XVIII centuries. The household genre also flourished in the art of Asian countries - in the miniature of Iran, India, in the painting of Korea and especially Japan (engravings by Kitagawa Utamaro, Katsushika Hokusai).

In the first half of the XIX century. in the aesthetic affirmation of everyday life, an important role was played by the idyllic image of the life of the peasantry and city dwellers, captivating with poetic simplicity and touching sincerity (A. Venetsianov and the Venetian school in Russia, J. K. Bingham and W. Mount in the USA, D. Wilkie in Scotland; representatives of the Biedermeier - G. F. Kersting and K. Spitzweg in Germany, F. Waldmuller in Austria, K. Köbke in Denmark).

French romantics (T. Géricault, A. G. Dean) introduced the spirit of protest, generalization and psychological richness of images into the everyday genre ordinary people; O. Daumier in the middle of the XIX century. developed these searches, supplementing them with a high skill of social typification.

HOUSEHOLD GENRE. France.

Courbet, Gustave. Hammock.

In the middle and second half of the XIX century. the everyday genre develops in the works of G. Courbet and J. F. Millet in France, A. Menzel and V. Leibl in Germany, J. Fattori in Italy, I. Israels in Holland, W. Homer in the USA, C. Meunier in Belgium .

The everyday genre of Russian critical realism was characterized by a deep and precise penetration into the spiritual world of the characters, a detailed narrative, and a detailed dramatic development of the plot.

These features, clearly manifested in the middle of the XIX century. in the paintings of P. Fedotov, were perceived by the genre-democrats V. Perov and P. Shmelkov.

On this basis, the everyday genre of the Wanderers grew up, which played a leading role in their art, which exclusively fully and accurately reflected the folk life of the second half of the 19th century. A detailed picture of the life of all strata of Russian society was given by G. Myasoedov, V. Maksimov, K. Savitsky, V. Makovsky, and - with special depth and scope - I. Repin, the breadth of the tasks of genre paintings of which often brought them closer to historical composition.

Genre and everyday features are manifested in portrait, landscape, historical and battle painting of a number of artists of the 19th century, among them - J. Bastien-Lepage, L. Lermit in France, L. Knaus, B. Botier in Germany, K. Makovsky in Russia and others. Artists associated with impressionism (E. Manet, E. Degas, O. Renoir in France), in the 1860-80s. asserted a new type of genre painting, in which they sought to capture, as it were, an accidental, fragmentary aspect of life, a sharp specificity in the appearance of characters, the unity of people and their natural environment.

These trends gave impetus to a freer interpretation of the everyday genre, a direct pictorial perception of everyday scenes (M. Lieberman in Germany, E. Werenschell, K. Krog in Norway, A. Zorn, Z. Yousefson in Sweden, W. Sickert in Great Britain, T. Aikins in the USA, V. Serov, F. Malyavin, K. Yuon in Russia).

At the turn of the XIX-XX centuries. in the art of symbolism and the Art Nouveau style, there is a break with the tradition of the everyday genre of the 19th century.

Everyday scenes are treated as timeless symbols; the vital concreteness of the image gives way to monumental and decorative tasks (E. Munch in Norway, F. Hodler in Switzerland, P. Gauguin in France, V. Borisov-Musatov in Russia).

Traditions of realistic everyday genre of the 19th century. were picked up in the 20th century. such artists as T. Steinlen in France, F. Brangvin in Great Britain, K. Kollwitz in Germany, D. Rivera in Mexico, J. Bellows in the USA, F. Mazerel in Belgium, D. Derkovich in Hungary, N. Balkansky in Bulgaria, S. Lukyan in Romania, M. Galand in Slovakia, etc.

After the Second World War, this direction was continued by the masters of neorealism - R. Guttuso, A. Pizzinato in Italy, A. Fugeron and B. Taslitsky in France, Ueno Makoto in Japan. A characteristic feature of the everyday genre was the combination of acutely perceived characteristic features of everyday life with generalization, often symbolism of images and situations.

In the countries of Asia and Africa, original schools of national everyday genre have developed, which have risen from imitation and stylization to a deep generalized reflection of the way of life of their peoples (A. Sher-Gil, K. K. Hebbar in India, K. Affandi in Indonesia, M. Sabri in Iraq, A. Tekle in Ethiopia, sculptors K. Antubam in Ghana, F. Ydubor in Nigeria).

Artists of modernist movements - pop art and hyperrealism - turn to everyday scenes.

The everyday genre played a crucial role in the development of Russian art of the 20th century. In the 20s. within the framework of this genre, P. Kuznetsov, M. Saryan, P. Konchalovsky, K. Petrov-Vodkin, artists of the OST association (A. Deineka, K. Pimenov) worked in the 30s. - S. Gerasimov, A. Plastov, T. Galonenko, V. Odintsov, F. Krichevsky.

The works of everyday genre reflected the difficult life of the front and rear during the Great Patriotic War (Yu. Neprintsev, B. Nemensky, A. Laktionov, V. Kostetsky, A. Pakhomov, L. Soyfertis), typical features of the everyday life in the postwar years (T Yablonskaya, S. Chuikov, F. Reshetnikov, S. Grigoriev, U. Dzhaparidze, E. Kalnyn, L. Ilyina).

Since the second half of the 50s. everyday genre is reflected in the paintings of G. Korzhev, V. Ivanov, E. Moiseenko, V. Popkov, T. Salakhov, D. Zhilinsky, E. Iltner, I. Zarin, I. Klychev, N. Andronov, A. and S Tkachev, T. Mirzashvili, S. Muradyan, in engravings by G. Zakharov, V. Tolli, V. Yurkunas and others.

The first paintings depicting scenes from life have been known since the time of rock art. Hunting for wild animals, cooking, ritual dances and sacrificial rites - these aspects of the daily existence of people were reflected in primitive drawings that have survived to this day.

However, the topic of everyday life was ignored by ancient masters, who believed that fine art should be sublime and refined, therefore there is no place for illustrations of everyday life in it.

The heyday of the everyday genre falls on the Renaissance, when values are rethought, and the main place in all types of art is given to man. Along with mythological subjects, many artists depict in their works ordinary people engaged in everyday activities.

However, everyday painting of this period is greatly embellished and elevated to the absolute - artists, by and large, sing of beauty human body, and everyday surroundings serve only as an addition, which is given secondary importance. Nevertheless, such artists as Peter Rubens and Diego Velázquez, Jan Vermeer of Delft, Jacob Jordaens and Adrian van Ostade are considered to be the founders of the everyday genre in painting, which was finally formed only in the 18th century.

By the end of the 17th century, two main trends emerged in the everyday genre of fine art. The Rococo cult dominated Europe, so it is not surprising that artists tried to edit everyday scenes, make them elegant and sophisticated. This is how “gallant painting” appeared, in which such masters as Karel Fabricius, Gerard Terborch, Antoine Watteau, Jean Baptiste Greuze, Jean Honore Fragonard, Francois Boucher and Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin were very successful. Their paintings reflected, as a rule, the life of the upper class, and were distinguished by the photographic accuracy of details.

At the same time, a socio-critical current of everyday painting developed in parallel, where reality was practically not embellished. Ordinary peasants became the heroes of the works of William Hogarth and Kim Hondo, Gustave Courbet and Giovanni Fattori, and everyday scenes with the participation of the aristocracy were often humorous.

In the second half of the 19th century, when a wave of impressionism swept over Europe, a new trend appeared in everyday painting, associated with the depiction of random scenes from people's lives. Fleeting sketches on the street turned into luxurious paintings, full of life and movement. To this day, the works of such painters as Edouard Manet, Auguste Renoir, Max Liebermann, Edgar Degas, Thomas Aikins and Anders Zorn are the standard of everyday genre in the visual arts.

Throughout the 20th century, everyday painting was an integral part of various trends and trends. The brightest representatives of avant-garde art and supporters of realism paid attention to her. However, this genre acquired a sharp social orientation only in Russia thanks to Alexander Laktionov, Fedor Reshetnikov, Arkady Plastov, Boris Kustodiev, Gleb Savinov, Yuri Pimenov, Tatyana Yablonskaya and Ivan Vladimirov.

|

HOUSEHOLD GENRE, a genre of fine art representing a real, usually contemporary artist everyday life. Plots of the everyday genre reflect the existing way of life - work and rest, weekdays and holidays, mores and customs, relationships between people. Elements of everyday genre were present in primitive images of hunting scenes and rituals, in art ancient world, saturated with everyday details, in European medieval art, which often included allegorically interpreted everyday motifs (cycles on the themes of 12 months, seasons, where seasonal activities are depicted, etc.). As an independent type of artistic creativity, the everyday genre first developed in the medieval art of the Far East: in China and Japan (ukiyo-e school), in the reliefs and paintings of Indian temples, and Persian miniatures. In the European art of the Proto-Renaissance and Renaissance (later by M. da Caravaggio and the artists of Caravagism), the features of the everyday genre appeared in the interpretation of religious subjects as real events with signs modern life. At the same time, the everyday genre is closely related to the parable or allegory (the cycles "Five Senses", "Virtue and Vices", etc.).

The everyday genre acquires autonomous significance in the 16th and 17th centuries. The plots of proverbs and sayings, games and riddles, as well as kitchens, shops, markets, meals have been depicted since the 16th century in the Dutch household genre (P. Brueghel the Elder, P. Artsen, I. Beikelaer). Close to the everyday genre of bodegones in Spanish art (D. Velazquez and others). The heyday of the everyday genre comes in Dutch and Flemish painting of the 17th century: scenes of burgher (J. Vermeer, G. Terborch) and peasant life (A. van Ostade), grotesque-comic plots by A. Brouwer and D. Teniers the Younger, “shops” F. Snyders, scenes of folk festivals by J. Jordans and P. P. Rubens. Thanks to the Dutchman P. van Laer, the comic household genre spread in Italy (bamboccianti). In the 18th century, A. Watteau wrote "gallant festivities" in the Rococo style; J. B. S. Chardin develops the tradition of contemplative everyday genre, following his French predecessors, the Le Nain brothers.

The everyday genre of the Enlightenment is moralistic (J. B. Greuze, W. Hogarth); in the era of romanticism, exotic oriental motifs penetrate it (E. Delacroix, O. Vernet). The everyday genre of the Biedermeier period is distinguished by poetization or anecdotal interpretation of private life (F. Waldmuller, K. Spitzweg). French realist artists, on the contrary, turn to the harsh and pious life of the provinces (F. Millet, G. Courbet); satire and social criticism are characteristic of O. Daumier's everyday genre. The everyday life of the townspeople, their work and leisure are at the center of the everyday genre of the masters of impressionism. In the middle - 2nd half of the 19th century, the life of industrial workers is sympathetically depicted in the works of F. M. Braun, A. von Menzel and C. Meunier; the theme of labor is also represented in the works of F. Brangvin, W. Van Gogh, H. von Mare, J. Segantini, F. Hodler, in Italian verismo. The reverse life of the metropolis of the 20th century is shown by the Berlin graphic artists G. Gross, K. Kollwitz and G. Zille, painters of the New York "School of the trash can", the national way of life - representatives of regionalism in the United States, costumbrism and muralism in Latin America, Italian neorealism.

In Russia, the everyday genre takes shape only in the 18th century. Engravings are saturated with everyday episodes (A.F. Zubov), in the painting of the 2nd half of the 18th century, both individual works on everyday topics (I.I. Firsov, I.I. Belsky), and entire series with scenes of peasant life ( I. A. Ermenev, I. M. Tankov, and M. Shibanov). Everyday life is poeticized in the paintings of V. A. Tropinin, A. G. Venetsianov and Venetian artists; satirical interpretation of everyday topics prevails in the work of P. A. Fedotov, graphics P. M. Shmelkov. In the second half of the 19th century, the genre of everyday life occupies a leading place in the system of genres, influencing the structure of the historical genre, portrait and landscape. The development of critical realism in Russian art is connected with the everyday genre of the Wanderers (V. G. Perov, I. E. Repin, V. E. Makovsky, N. A. Kasatkin, N. A. Yaroshenko, A. E. Arkhipov and others. ). At the same time, the salon household genre is developing, in which the idealized life of both the past and the present is presented (F. A. Bronnikov, K. E. Makovsky). The way of provincial Russia was sung by B. M. Kustodiev and M. V. Nesterov. In sculpture, the everyday genre is represented by M. M. Antokolsky, E. A. Lansere and M. A. Chizhov, then by V. A. Beklemishev, P. P. Trubetskoy and S. T. Konenkov.

In Russia, the everyday genre takes shape only in the 18th century. Engravings are saturated with everyday episodes (A.F. Zubov), in the painting of the 2nd half of the 18th century, both individual works on everyday topics (I.I. Firsov, I.I. Belsky), and entire series with scenes of peasant life ( I. A. Ermenev, I. M. Tankov, and M. Shibanov). Everyday life is poeticized in the paintings of V. A. Tropinin, A. G. Venetsianov and Venetian artists; satirical interpretation of everyday topics prevails in the work of P. A. Fedotov, graphics P. M. Shmelkov. In the second half of the 19th century, the genre of everyday life occupies a leading place in the system of genres, influencing the structure of the historical genre, portrait and landscape. The development of critical realism in Russian art is connected with the everyday genre of the Wanderers (V. G. Perov, I. E. Repin, V. E. Makovsky, N. A. Kasatkin, N. A. Yaroshenko, A. E. Arkhipov and others. ). At the same time, the salon household genre is developing, in which the idealized life of both the past and the present is presented (F. A. Bronnikov, K. E. Makovsky). The way of provincial Russia was sung by B. M. Kustodiev and M. V. Nesterov. In sculpture, the everyday genre is represented by M. M. Antokolsky, E. A. Lansere and M. A. Chizhov, then by V. A. Beklemishev, P. P. Trubetskoy and S. T. Konenkov.

In Soviet art, special forms of everyday genre have developed: official pomposity (V. P. Efanov), satirical ridicule of the “old way of life” and its remnants (Kukryniksy), heroism (painters of a severe style), idyllic depiction of the “happy life” of the new society (S. V. Gerasimov). A number of exhibitions of the Academy of Arts of the Russian Republic were entirely devoted to the everyday theme. Artists recreate the life of a village (A. A. Plastov), a city (Yu. I. Pimenov), a family (P. P. Konchalovsky). Industrial life is reflected in the paintings of P. I. Kotov, various aspects the children's theme was revealed by F. S. Bogorodsky and F. P. Reshetnikov, the youth and sports theme - by A. A. Deineka and S. A. Luchishkin. The tragedy of wartime life is represented in the paintings of T. G. Gaponenko, the graphics of N. I. Dormidontov, and others; the optimism of the post-war decade was reflected in the works of A. I. Laktionov, V. G. Odintsov and V. N. Yakovlev. The everyday genre is widely represented in sculpture (N. Ya. Danko, V. V. Lishev, G. I. Motovilov). Since the 1960s, the idealization of Soviet life has been opposed by an ironic trend in the works of the underground and Sots Art.

In Soviet art, special forms of everyday genre have developed: official pomposity (V. P. Efanov), satirical ridicule of the “old way of life” and its remnants (Kukryniksy), heroism (painters of a severe style), idyllic depiction of the “happy life” of the new society (S. V. Gerasimov). A number of exhibitions of the Academy of Arts of the Russian Republic were entirely devoted to the everyday theme. Artists recreate the life of a village (A. A. Plastov), a city (Yu. I. Pimenov), a family (P. P. Konchalovsky). Industrial life is reflected in the paintings of P. I. Kotov, various aspects the children's theme was revealed by F. S. Bogorodsky and F. P. Reshetnikov, the youth and sports theme - by A. A. Deineka and S. A. Luchishkin. The tragedy of wartime life is represented in the paintings of T. G. Gaponenko, the graphics of N. I. Dormidontov, and others; the optimism of the post-war decade was reflected in the works of A. I. Laktionov, V. G. Odintsov and V. N. Yakovlev. The everyday genre is widely represented in sculpture (N. Ya. Danko, V. V. Lishev, G. I. Motovilov). Since the 1960s, the idealization of Soviet life has been opposed by an ironic trend in the works of the underground and Sots Art.

Lit.: Russian genre painting. M., 1961; Langdon H. Everyday-life painting. Oxf., 1979; Brook Ya. V. At the origins of the Russian genre. XVIII century. M., 1990; Sokolov M.N. Everyday images in Western European painting of the 15th-17th centuries. Reality and symbolism. M., .