What century does the term Decembrists belong to? What you need to know about the Decembrists. How did they differ from other revolutionaries

In the first quarter of the 19th century in Russia, a revolutionary ideology was born, the bearers of which were the Decembrists. Disillusioned with the policy of Alexander 1, a part of the progressive nobility decided to do away with the reasons, as it seemed to them, for the backwardness of Russia.

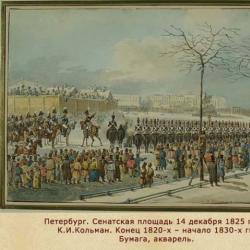

The attempted coup d'état, which took place in St. Petersburg, the capital of the Russian Empire, on December 14 (26), 1825, was called the Decembrist Uprising. The uprising was organized by a group of like-minded nobles, many of them were guard officers. They tried to use the guards to prevent the accession to the throne of Nicholas I. The goal was the abolition of the autocracy and the abolition of serfdom.

In February 1816, the first secret political society arose in St. Petersburg, the purpose of which was the abolition of serfdom and the adoption of a constitution. It consisted of 28 members (A.N. Muravyov, S.I. and M.I. Muravyov-Apostles, S.P.T. Rubetskoy, I.D. Yakushkin, P.I. Pestel, etc.)

In 1818, the organization " Welfare Union”, which had 200 members and had councils in other cities. The society promoted the idea of abolishing serfdom, preparing a revolutionary coup by the officers. " Welfare Union” fell apart due to disagreements between the radical and moderate members of the union.

In March 1821 in Ukraine arose Southern society headed by P.I. Pestel, who was the author of the program document " Russian Truth».

Petersburg, on the initiative of N.M. Muravyov was created " northern society”, which had a liberal plan of action. Each of these societies had its own program, but the goal was the same - the destruction of autocracy, serfdom, estates, the creation of a republic, the separation of powers, the proclamation of civil liberties.

Preparations began for an armed uprising. The conspirators decided to take advantage of the difficult legal situation that had developed around the rights to the throne after the death of Alexander I. On the one hand, there was a secret document confirming the long-standing renunciation of the throne by the brother, Konstantin Pavlovich, who followed the childless Alexander in seniority, which gave an advantage to the next brother, extremely unpopular among the highest military-bureaucratic elite Nikolai Pavlovich. On the other hand, even before the opening of this document, Nikolai Pavlovich, under pressure from the Governor-General of St. Petersburg, Count M.A. Miloradovich, hastened to renounce his rights to the throne in favor of Konstantin Pavlovich. After the repeated refusal of Konstantin Pavlovich from the throne, the Senate, as a result of a long night meeting on December 13-14, 1825, recognized the legal rights to the throne of Nikolai Pavlovich.

The Decembrists decided to prevent the Senate and the troops from taking the oath to the new tsar.

The conspirators planned to occupy the Peter and Paul Fortress and the Winter Palace, arrest the royal family and, if certain circumstances arise, kill them. Sergei Trubetskoy was elected to lead the uprising. Further, the Decembrists wanted to demand from the Senate the publication of a national manifesto proclaiming the destruction of the old government and the establishment of a provisional government. Admiral Mordvinov and Count Speransky were supposed to be members of the new revolutionary government. The deputies were entrusted with the task of approving the constitution - the new fundamental law. If the Senate refused to announce a national manifesto containing items on the abolition of serfdom, the equality of all before the law, democratic freedoms, the introduction of compulsory military service for all classes, the introduction of a jury trial, the election of officials, the abolition of the poll tax, etc., it was decided to force him do it forcibly. Then it was planned to convene an All-People's Council, which would decide on the choice of a form of government: a republic or a constitutional monarchy. If a republican form had been chosen, the royal family would have had to be expelled from the country. Ryleev at first suggested sending Nikolai Pavlovich to Fort Ross, but then he and Pestel conceived the murder of Nikolai and, perhaps, Tsarevich Alexander.

On the morning of December 14, 1825, the Moscow Life Guards Regiment entered Senate Square. He was joined by the Guards Naval Crew and the Life Guards Grenadier Regiment. In total, about 3 thousand people gathered.

However, Nicholas I, informed of the impending conspiracy, took the oath of the Senate in advance and, having pulled the troops loyal to him, surrounded the rebels. After negotiations, in which Metropolitan Seraphim and the Governor-General of St. Petersburg M.A. Miloradovich (who was mortally wounded) took part on the part of the government, Nicholas I ordered the use of artillery. The uprising in Petersburg was crushed.

But already on January 2, it was suppressed by government troops. Arrests of participants and organizers began all over Russia. In the case of the Decembrists, 579 people were involved. Found guilty 287. Five were sentenced to death and executed (K.F. Ryleev, P.I. Pestel, P.G. Kakhovskiy, M.P. Bestuzhev-Ryumin, S.I. Muravyov-Apostol). 120 people were exiled to hard labor in Siberia or to a settlement.

About one hundred and seventy officers involved in the case of the Decembrists, out of court, were demoted to soldiers and sent to the Caucasus, where the Caucasian war was going on. Several exiled Decembrists were later sent there. In the Caucasus, some, like M. I. Pushchin, deserved to be promoted to officers by their courage, and some, like A. A. Bestuzhev-Marlinsky, died in battle. Individual members of the Decembrist organizations (such as, for example, V. D. Volkhovsky and I. G. Burtsev) were transferred to the troops without demotion into soldiers, which took part in the Russian-Persian war of 1826-1828 and the Russian-Turkish war of 1828-1829 . In the mid-1830s, a little over thirty Decembrists who had served in the Caucasus returned home.

The verdict of the Supreme Criminal Court on the death penalty for five Decembrists was executed on July 13 (25), 1826 in the kronverk of the Peter and Paul Fortress.

During the execution, Muraviev-Apostol, Kakhovsky and Ryleev fell off the noose and were hanged a second time. There is an erroneous opinion that this was contrary to the tradition of the inadmissibility of the second execution of the death penalty. According to military Article No. 204, it is stated that " Carry out the death penalty before the end result ”, that is, until the death of the convicted person. The procedure for the release of a convict who had fallen, for example, from the gallows, that existed before Peter I, was canceled by the Military Article. On the other hand, the “marriage” was explained by the absence of executions in Russia over the past several decades (the exception was the executions of participants in the Pugachev uprising).

On August 26 (September 7), 1856, on the day of his coronation, Emperor Alexander II pardoned all the Decembrists, but many did not live to see their release. It should be noted that Alexander Muravyov, the founder of the Union of Salvation, who was sentenced to exile in Siberia, was already appointed mayor in Irkutsk in 1828, then held various responsible positions, up to governorships, and participated in the abolition of serfdom in 1861.

For many years, and even today, it is not uncommon for the Decembrists in general and the leaders of the coup attempt to idealize and give them an aura of romanticism. However, it must be admitted that these were ordinary state criminals and traitors to the Motherland. Not for nothing in the Life of St. Seraphim of Sarov, who usually met any person with exclamations " My joy!", there are two episodes that contrast sharply with the love with which Saint Seraphim treated everyone who came to him ...

Go where you came from

Sarov monastery. Elder Seraphim, all imbued with love and kindness, looks sternly at the officer approaching him and refuses to bless him. The seer knows that he is a participant in the conspiracy of the future Decembrists. " Go where you came from ', the reverend resolutely tells him. Then the great elder brings his novice to the well, the water in which was muddy and dirty. " So this man who came here intends to outrage Russia ”, - said the righteous man, jealous of the fate of the Russian monarchy.

Troubles will not end well

Two brothers arrived in Sarov and went to the elder (these were the two Volkonsky brothers); he accepted one of them and blessed, but did not allow the other to approach him, waved his hands and drove away. And he told his brother about him that he was plotting evil, that troubles would not end well, and that many tears and blood would be shed, and advised him to come to his senses in time. And sure enough, the one of the two brothers whom he drove away got into trouble and was exiled.

Note. Major General Prince Sergei Grigoryevich Volkonsky (1788-1865) was a member of the Welfare Union and the Southern Society; convicted in the first category and, upon confirmation, sentenced to hard labor for 20 years (the term was reduced to 15 years). Sent to the Nerchinsk mines, and then transferred to the settlement.

So looking back, we must admit that it was bad, the Decembrists were executed. It's too bad that only five of them were executed...

And in our time, it must be clearly understood that any organization that aims (openly or covertly) to organize unrest in Russia, excite public opinion, organize confrontation actions, as happened in poor Ukraine, the armed overthrow of power, etc. - is subject to immediate closure, and the organizers - to the court, as criminals against Russia.

Lord, deliver our fatherland from disorder and internecine strife!

Decembrists Russian revolutionaries who raised an uprising in December 1825 against the autocracy and serfdom (they got their name from the month of the uprising). D. were revolutionaries of the nobility, their class limitations left a stamp on the movement, which, according to slogans, was anti-feudal and associated with the maturation of the prerequisites for a bourgeois revolution in Russia. The process of disintegration of the feudal-serf system, which was clearly manifested already in the second half of the 18th century. and intensified at the beginning of the 19th century, was the basis on which this movement grew. V. I. Lenin called the era of world history between the Great French Revolution and the Paris Commune (1789-1871) "... the era of bourgeois-democratic movements in general, bourgeois-national in particular, the era of the rapid breakdown of feudal-absolutist institutions that have outlived themselves" (Full sobr. soch., 5th ed., vol. 26, p. 143). The Dagestan movement was an organic element in the struggle of that era. The anti-feudal movement in the world-historical process often included elements of noble revolutionary spirit, which were strong in the English Revolution of the 17th century, in the Spanish liberation struggle of the 1820s. and were especially clearly manifested in the Polish movement of the 19th century. Russia was no exception in this respect. The weakness of the Russian bourgeoisie contributed to the fact that the "first-born of freedom" in Russia were the revolutionary nobles. The Patriotic War of 1812, in which almost all the founders and many active members of the future Danish movement took part, and the subsequent foreign campaigns of 1813–14 were, to a certain extent, a political school for them. In 1816, young officers A. Muravyov (See Muravyov), S.

Trubetskoy, I. Yakushkin, S. Muravyov-Apostol (See Muravyov-Apostol) and M. Muravyov-Apostol (See Muravyov-Apostol), N. Muravyov (See Muravyov) founded the first secret political society - "Union of Salvation" , or "The Society of True and Faithful Sons of the Fatherland". Later, P. Pestel and others joined it - about 30 people in total. The work on improving the program and the search for more perfect methods of action for the elimination of absolutism and the abolition of serfdom led in 1818 to the closure of the "Union of Salvation" and the foundation of a new, wider society - the "Union of Welfare" (See Union of Welfare) (about 200 people.) . The new society considered the formation of "public opinion" in the country, which seemed to D. the main revolutionary force driving public life, to be the main goal. In 1820, a meeting of the governing body of the "Union of Welfare" - the Root Council - on the report of Pestel unanimously voted for the republic. It was decided to make the main force of the coup an army led by members of a secret society. The performance in the Semyonovsky regiment (1820) in St. Petersburg that took place before D.’s eyes additionally convinced D. that the army was ready to move (the soldiers of one of the companies protested against the cruel treatment of the regiment commander Schwartz. The company was sent to the Peter and Paul Fortress. The rest of the companies also refused to obey commanders, after which the entire regiment was sent to the fortress, and then disbanded). According to D., the revolution was to be made for the people, but without their participation. Eliminate the active participation of the people in the coming upheaval seemed to D. necessary in order to avoid the "horrors of the people's revolution" and retain a leading position in the revolutionary events. The ideological struggle within the organization, in-depth work on the program, the search for better tactics, more effective organizational forms required a deep internal restructuring of society. In 1821, the congress of the Indigenous Council of the Union of Welfare in Moscow declared the society dissolved and, under the cover of this decision, which made it easier to screen out unreliable members, began to form a new organization. As a result, the Southern Society of Decembrists was formed in 1821 (in the Ukraine, in the quartering area of the 2nd Army), and soon after, the Northern Society of Decembrists, with its center in St. Petersburg. One of the outstanding D. - Pestel became the head of the Southern Society. Members of the Southern Society were opponents of the idea of the Constituent Assembly and supporters of the dictatorship of the Provisional Supreme Revolutionary Board. It was the latter, in their opinion, that was to take power into its own hands after a successful revolutionary coup and introduce a pre-prepared constitutional device, the principles of which were set out in a document later called Russkaya Pravda (See Russkaya Pravda). Russia was declared a republic, serfdom was immediately abolished. The peasants were liberated with land. However, Pestel's agrarian project did not provide for the complete destruction of landownership. Russkaya Pravda pointed to the need for the complete destruction of the estate system, the establishment of the equality of all citizens before the law; proclaimed all basic civil liberties: speech, press, assembly, religion, equality in court, movement and choice of occupation. Russkaya Pravda fixed the right of every man who has reached the age of 20 to participate in the political life of the country, to elect and be elected without any property or educational qualifications. Women did not receive voting rights. Each volost was to meet annually in the Zemsky People's Assembly, which elected deputies to the permanent representative bodies of local government. The unicameral People's Council - the Russian parliament - was endowed with full legislative power in the country; executive power in the republic belonged to the Sovereign Duma, which consisted of 5 members elected by the People's Council for 5 years. Every year one of them dropped out and one new one was chosen instead - this ensured the continuity and succession of power and its constant renewal. That member of the State Duma, who had been in its composition for the last year, became its chairman, in fact, the president of the republic. This ensured the impossibility of usurping the supreme power: each president held his post for only one year. The third, very peculiar, supreme state body of the republic was the Supreme Council, which consisted of 120 people elected for life, with regular payment for the performance of their duties. The only function of the Supreme Council was control ("guardian"). He had to see to it that the constitution was strictly observed. The Russkaya Pravda indicated the composition of the future territory of the state - Transcaucasia, Moldavia and other territories, the acquisition of which Pestel considered necessary for economic or strategic reasons, were to enter Russia. The democratic system was supposed to spread in exactly the same way to all Russian territories, regardless of what peoples they were inhabited. Pestel was, however, a resolute opponent of the federation: all of Russia, according to his project, was supposed to be a single and indivisible state. An exception was made only for Poland, which was granted the right to secede. It was assumed that Poland, together with all of Russia, would take part in the revolutionary upheaval planned by D. and, in accordance with Russkaya Pravda, would carry out the same revolutionary transformations that were supposed for Russia. Pestel's "Russian Truth" was repeatedly discussed at the congresses of the Southern Society, its principles were accepted by the organization. The surviving editions of Russkaya Pravda testify to the continuous work on its improvement and the development of its democratic principles. Being mainly Pestel's creation, Russkaya Pravda was also edited by other members of the Southern Society. The northern society of Dagestan was headed by N. Muravyov; the leading core included N. Turgenev, M. Lunin, S. Trubetskoy, E. Obolensky. The constitutional project of the Northern Society was developed by N. Muravyov. It advocated the idea of a Constituent Assembly. Muravyov strongly objected to the dictatorship of the Provisional Supreme Revolutionary Government and the dictatorial introduction of a revolutionary constitution approved in advance by a secret society. Only the future Constituent Assembly could, in the opinion of the Northern Society of Denmark, draw up a constitution or approve any of the constitutional projects. The constitutional project of N. Muravyov was supposed to be one of them. N. Muravyov's "Constitution" is a significant ideological document of the Democratic movement. In its project, class limitations affected much more than in Russkaya Pravda. The future Russia was to become a constitutional monarchy with a simultaneous federal structure. The principle of federation, close in type to the United States, did not take into account the national moment at all - the territorial one prevailed in it. Russia was divided into 15 federal units - "powers" (regions). The program provided for the unconditional abolition of serfdom. Estates were destroyed. The equality of all citizens before the law, equal court for all were established. However, the agrarian reform of N. Muravyov was class-limited. According to the latest version of the "Constitution", the peasants received only estate land and 2 dec. arable land per yard, the rest of the land remained the property of the landowners or the state (state lands). The political structure of the federation provided for the device of a bicameral system (a kind of local parliament) in each "power". The upper chamber in the "power" was the State Duma, the lower - the Chamber of Elected Deputies of the "power". The federation as a whole was united by the People's Council - a bicameral parliament. The people's council held legislative power. Elections to all representative institutions were conditioned by a high property qualification. The executive power belonged to the emperor - the supreme official of the Russian state, who received a large salary. The emperor did not have legislative power, but he had the right of a “suspensive veto”, that is, he could delay the adoption of a law for a certain period and return it to parliament for a second discussion, but he could not completely reject the law. The "Constitution" of N. Muravyov, like Pestel's "Russian Truth", declared the basic civil freedoms: speech, press, assembly, religion, movement, and others. In the last years of the activities of the secret Northern Society, the struggle of internal currents became more pronounced in it. The republican trend, represented by the poet K. F. Ryleev, who joined the society in 1823, and also by E. Obolensky, the Bestuzhev brothers (Nikolai, Alexander, and Mikhail), and other members, gained strength again. The entire burden of preparing the uprising in Petersburg fell on this republican group. Southern and Northern societies were in continuous communication, discussing their differences. A congress of the Northern and Southern Societies was scheduled for 1826, at which it was supposed to work out a common constitutional foundation. However, the situation in the country forced D. to speak ahead of schedule. In preparation for an open revolutionary action, the Southern Society united with the Society of United Slavs (See Society of United Slavs). This society in its original form arose back in 1818 and, having gone through a series of transformations, set as its ultimate goal the destruction of serfdom and autocracy, the creation of a democratic Slavic federation consisting of Russia, Poland, Bohemia, Moravia, Hungary (members of the society considered the Hungarians to be Slavs), Transylvania , Serbia, Moldavia, Wallachia, Dalmatia and Croatia. Members of the Slavic society were supporters of popular revolutions. The "Slavs" accepted the program of the southerners and joined the Southern society. In November 1825, Tsar Alexander I suddenly died. His older brother Konstantin had renounced the throne long before that, but the royal family kept his refusal a secret. Alexander I was to be succeeded by his brother Nicholas, who had long been hated in the army as a rude martinet and Arakcheev (see Arakcheevshchina). Meanwhile, the army swore allegiance to Constantine. However, rumors soon spread about taking a new oath - to Emperor Nicholas. The army was worried, discontent in the country increased. At the same time, members of D.'s secret society became aware that spies had discovered their activities (denunciations by I. Sherwood and A. Maiboroda). It was impossible to wait. Since the decisive events of the interregnum played out in the capital, it naturally became the center of the upcoming coup. The Northern Society decided on an open armed uprising in St. Petersburg and scheduled it for December 14, 1825 - the day when the oath to the new emperor Nicholas I was to take place. The plan for a revolutionary coup, elaborated in detail at D.'s meetings in Ryleev's apartment, was to obstruct the oath, raise troops sympathetic to D., bring them to Senate Square, and by force of arms (if negotiations do not help) prevent the Senate and State Council from taking the oath to the new emperor. The deputation from D. was supposed to force the senators (if necessary, by military force) to sign a revolutionary manifesto to the Russian people. The manifesto announced the overthrow of the government, abolished serfdom, abolished recruitment, declared civil liberties and convened a Constituent Assembly, which would finally decide the question of the constitution and form of government in Russia. Prince S. Trubetskoy, an experienced military man, a participant in the war of 1812, well known to the guards, was elected the "dictator" of the upcoming uprising. The first insurgent regiment (of the Moscow Life Guards) arrived at Senate Square on December 14 at about 11 a.m. under the leadership of A. Bestuzhev, his brother Mikhail, and D. Shchepin-Rostovsky (See Shchepin-Rostovsky). The regiment lined up in a square near the monument to Peter I. Only 2 hours later, the Life Guards Grenadier Regiment and the Guards Naval Crew joined it. In total, about 3 thousand rebel soldiers gathered on the square under the banners of the uprising, with 30 combatant commanders - officers-D. The assembled sympathetic people greatly outnumbered the troops. However, the goals set by D. were not achieved. Nicholas I managed to swear in the Senate and the State Council while it was still dark, when the Senate Square was empty. The "dictator" Trubetskoy did not appear on the square. The square of the rebels several times reflected the onslaught of the guards cavalry that remained loyal to Nicholas with quick fire. An attempt by the Governor-General Miloradovich to persuade the rebels was not successful. Miloradovich was mortally wounded by the Decembrist P. Kakhovsky (See Kakhovsky). By evening, D. chose a new leader - Prince Obolensky, the chief of staff of the uprising. But it was already too late. Nikolai, who managed to pull the troops loyal to him to the square and surround the squares of the rebels, was afraid that "the excitement would not be transmitted to the mob", and ordered the shooting with grapeshot. According to clearly underestimated government figures, more than 80 "rebels" were killed on Senate Square. By nightfall, the uprising was crushed. The news of the defeat of the uprising in St. Petersburg reached the Southern Society in the twentieth of December. Pestel had already been arrested by that time (December 13, 1825), but nevertheless the decision to speak was made. The uprising of the Chernigov regiment (see the uprising of the Chernigov regiment) was led by Lieutenant Colonel S. Muravyov-Apostol and M. Bestuzhev-Ryumin. It began on December 29, 1825 in the village. Triles (about 70 km southwest of Kyiv), where the 5th company of the regiment was stationed. The rebels (a total of 1164 people) captured the city of Vasilkov and moved from there to join with other regiments. However, not a single regiment supported the initiatives of the Chernigovites, although the troops were undoubtedly in ferment. A detachment of government troops sent to meet the rebels met them with volleys of buckshot. On January 3, 1826, the uprising of D. in the south was crushed. During the uprising in the south, appeals by D. were distributed among the soldiers and partly the people. The revolutionary "Catechism", written by S. Muravyov-Apostol and Bestuzhev-Ryumin, freed the soldiers from the oath to the tsar and was imbued with the republican principles of popular government. 579 people were involved in the investigation and trial in D.'s case. Investigative and judicial procedures were carried out in deep secrecy. Five leaders - Pestel, S. Muravyov-Apostol, Bestuzhev-Ryumin, Ryleev and Kakhovsky - were hanged on July 13, 1826. Exiled to Siberia for hard labor and settlement 121 D. Over 1000 soldiers were driven through the ranks, some were exiled to Siberia for hard labor or settlement, over 2,000 soldiers were transferred to the Caucasus, where hostilities were taking place at that time. The newly formed penal Chernihiv regiment, as well as other combined regiments of active participants in the uprising, were also sent to the Caucasus. The uprising of Dagestan occupies an important place in the history of the revolutionary movement in Russia. This was the first open action with weapons in hand in order to overthrow the autocracy and abolish serfdom. V. I. Lenin begins with D. the periodization of the Russian revolutionary movement. The significance of the movement of D. was already understood by their contemporaries: “Your mournful work will not be wasted,” A. S. Pushkin wrote in his message to D. in Siberia. Russian revolutionaries who were inspired by the feat of D. The profiles of five executed D. on the cover of Herzen's Polar Star were a symbol of the struggle against tsarism. A remarkable page in the history of the Russian revolutionary movement was the feat of the wives of those sentenced to hard labor D., who voluntarily followed their husbands to Siberia. Having overcome numerous obstacles, the first (in 1827) to arrive at the mines of Transbaikalia were M. N. Volkonskaya, A. G. Muravyova (with her A. S. Pushkin conveyed the message “In the depths of Siberian ores” to the Decembrists) and E. I. Trubetskaya. In 1828-31, the following arrived in Chita and the Petrovsky Zavod: Annenkova's bride - Polina Gebl (1800-76), Ivashev's bride - Camille Le Dantu (1803-39), the wives of the Decembrists A. I. Davydova, A. V. Entaltseva (died 1858 ), E. P. Naryshkina (1801-67), A. V. Rosen (died 1884), N. D. Fonvizina (1805-69), M. K. Yushnevskaya (b. 1790) and others. Departing for Siberia , they were deprived of noble privileges and moved to the position of wives of convicts, limited in the rights of movement, correspondence, disposal of their property, etc. They did not have the right to take their children with them, and return to European Russia was not always allowed even after the death of their husbands. Their feat is poeticized by N. A. Nekrasov in the poem "Russian Women" (original title - "Decembrists"). Many other wives, mothers and sisters of D. stubbornly sought permission to leave for Siberia, but were refused. D. made a significant contribution to the history of Russian culture, science and education. One of the prominent poets of the early 19th century. was K. F. Ryleev, whose work is permeated with revolutionary and civic motives. The poet A. Odoevsky is the author of D.'s poetic response to Pushkin's message to Siberia. From this answer, V. I. Lenin took the words “A flame will ignite from a spark” as an epigraph to the Iskra newspaper. A. A. Bestuzhev was the author of numerous works of art and critical articles. A significant literary heritage was left by the Dynasty poets: V. K. Kyuchelbeker, V. F. Raevsky, F. N. Glinka, N. A. Chizhov and others. treatises on history, economics, etc., valuable technical inventions. D. Peru - G. S. Batenkov a, M. F. Orlov a, N. I. Turgeneva - belong to works on issues of the Russian economy. The problems of Russian history are reflected in the works of N. M. Muravyov, A. O. Kornilovicha, P. A. Mukhanova, and V. I. Shteingel. D. - D. I. Zavalishin, G. S. Batenkov, N. A. Chizhov, K. P. Thorson made an important contribution to the development of Russian geographical science. The materialist philosophers were D. V. F. Raevsky, A. P. Baryatinsky, I. D. Yakushkin, N. A. Kryukov, and others. N. M. Murav’ev, P. I. Pestel’, and I. G. Burtsov left a number of works on military affairs and military history. D.'s activity in the field of Russian culture and science had a strong influence on the development of many social ideas and institutions in Russia. D. were passionate educators. They fought for advanced ideas in pedagogy, constantly propagating the idea that education should become the property of the people. They advocated advanced, anti-scholastic teaching methods adapted to child psychology. Even before the uprising, D. took an active part in the dissemination of schools for the people according to the Lancastrian system of education (V. Kuchelbecker, V. Raevsky, and others), which pursued the goals of mass education. D.'s educational activities played an important role in Siberia. Source: Decembrist uprising. Materials and documents, vol. 1-12, M. - L., 1925-69; Decembrists and secret societies in Russia. Official documents, M., 1906; Decembrists. Unpublished materials and articles, M., 1925; Rebellion of the Decembrists, L., 1926; Decembrists and their time, vol. 1-2, M., 1928-32; In memory of the Decembrists. Sat. materials, vol. 1-3, L., 1926; Decembrists. Letters and archival materials, M., 1938; Secret societies in Russia at the beginning of the XIX century. Sat. materials, articles, memoirs, M., 1926; Decembrist writers, Prince. 1-2, M., 1954-56 (Literary heritage, vol. 59-60); Decembrists. New materials, M., 1955; Decembrists in Transbaikalia, Chita, 1925; Volkonskaya M.N., Notes, 2nd ed., Chita, 1960; Annenkova P., Memoirs, 2nd ed., M., 1932; Pyx Decembrists in Ukraine. , Har., 1926. Op.: Selected. socio-political and philosophical works of the Decembrists, vol. 1-3, M., 1951; Decembrists. Poetry, drama, prose, journalism, literary criticism, M. - L., 1951. Lit.: Lenin V.I., Poln. coll. soch., 5th ed., vol. 5, p. thirty; ibid., vol. 26, p. 107; ibid., vol. 30, p. 315; Plekhanov G. V., December 14, 1825, Soch., vol. 10, M. - P., 1924; Shchegolev P. E., Decembrists, M. - L., 1926; Gessen S. [Ya.], Soldiers and sailors in the Decembrist uprising, M., 1930; Aksenov K. D., Northern Society of Decembrists, L., 1951; Decembrists in Siberia. [Sb.], Novosib., 1952; Gabov G. I., Socio-political and philosophical views of the Decembrists, M., 1954; Essays on the history of the Decembrist movement. Sat. Art., M., 1954; Nechkina M.V., Movement of the Decembrists, vol. 1-2, M., 1955; Olshansky P. N., Decembrists and the Polish national liberation movement, M., 1959; Chernov S. N., At the origins of the Russian liberation movement, Saratov, 1960; The wives of the Decembrists. Sat. Art., M., 1906; Gernet M.N., History of the royal prison, 3rd ed., vol. 2, M., 1961; Shatrova G.P., Decembrists and Siberia, Tomsk, 1962; Bazanov VG, Essays on Decembrist Literature. Publicism. Prose. Criticism, M., 1953; his, Essays on Decembrist Literature. Poetry, M., 1961; Lisenko M.[M.], Decembrist Rukh in Ukraine. K., 1954; Decembrist movement. Index of Literature, 1928-1959, M., 1960. M. V. Nechkina. Decembrist revolt. Great Soviet Encyclopedia. - M.: Soviet Encyclopedia.

1969-1978

.

190 years ago, Russia experienced events that, with a certain convention, can be considered an attempt to make the first Russian revolution. In December 1825 and January 1826, there were two armed uprisings organized by the Northern and Southern secret societies of the Decembrists.

The organizers of the uprising set themselves very ambitious tasks - changing the political system (replacing autocracy with a constitutional monarchy or republic), creating a constitution and parliament, and abolishing serfdom.

Until that moment, armed uprisings were either large-scale riots (in the terminology of the Soviet period - peasant wars) or palace coups.

Against this background, the Decembrist uprising was a political event of a completely different nature, hitherto unknown in Russia.

The large-scale plans of the Decembrists crashed into reality, in which the new emperor Nicholas I managed to firmly and decisively put an end to the performance of the fighters against the autocracy.

As you know, a failed revolution is called a rebellion, and its organizers will face a very unenviable fate.

A new court was established to consider the "case of the Decembrists"

Nicholas I approached the matter carefully. By decree of December 29, 1825, a Commission was established for research on malicious societies, chaired by the Minister of War Alexandra Tatishcheva. The Manifesto of June 13, 1826 established the Supreme Criminal Court, which was supposed to consider the “case of the Decembrists”.

About 600 people were involved in the investigation into the case. The Supreme Criminal Court sentenced 120 defendants in 11 different categories, ranging from the death penalty to deprivation of rank and demotion to the soldiers.

Here it must be borne in mind that we are talking about the nobles who participated in the uprising. The cases of soldiers were considered separately by the so-called Special Commissions. According to their decision, more than 200 people were subjected to "wire through the ranks" and other corporal punishment, and more than 4 thousand were sent to fight in the Caucasus.

"Wire through the ranks" was a punishment in which the condemned passed through the ranks of soldiers, each of whom stabbed him with a gauntlet (a long, flexible and thick rod of willow). When the number of such blows reached several thousand, such punishment turned into a sophisticated form of the death penalty.

As for the Decembrist nobles, the Supreme Criminal Court, based on the laws of the Russian Empire, issued 36 death sentences, of which five involved quartering, and another 31 beheading.

“An exemplary execution will be their just retribution”

The emperor had to approve the sentences of the Supreme Criminal Court. Nicholas I commuted the punishment for convicts in all categories, including those sentenced to death. Everyone who was to be beheaded, the monarch saved his life.

It would be a strong exaggeration to say that the fate of the Decembrists was decided by the Supreme Criminal Court on its own. Historical documents published after February 1917 show that the emperor not only followed the process, but also clearly imagined its outcome.

“Regarding the main instigators and conspirators, an exemplary execution will be their just retribution for violating public peace,” Nikolai wrote to the members of the court.

The monarch also instructed the judges as to exactly how the criminals should be executed. The quartering, provided for by law, was rejected by Nicholas I as a barbaric method unsuitable for a European country. Execution was also not suitable, since the emperor considered the convicts unworthy of execution, which allowed the officers not to lose dignity.

All that remained was hanging, to which the court ultimately sentenced five Decembrists. On July 22, 1826, the death sentence was finally approved by Nicholas I.

The leaders of the Northern and Southern societies were subject to the death penalty Kondraty Ryleev And Pavel Pestel, and Sergey Muravyov-Apostol And Mikhail Bestuzhev-Ryumin, who directly led the uprising of the Chernigov regiment. The fifth person sentenced to death was Pyotr Kakhovsky, who mortally wounded the governor-general of St. Petersburg on Senate Square Mikhail Miloradovich.

The infliction of a mortal wound on Miloradovich on December 14, 1825. Engraving from a drawing by G. A. Miloradovich. Source: Public Domain

The execution was practiced on sandbags

The news that the Decembrists will ascend the scaffold came as a shock to Russian society. From the time of the empress Elizabeth Petrovna death sentences in Russia were not carried out. Emeliana Pugacheva and his comrades were not taken into account, since they were talking about commoner rebels. The execution of the nobles, even if they encroached on the state system, was an event out of the ordinary.

The defendants themselves, both those who were sentenced to death and those who were sentenced to other types of punishment, learned about their fate on July 24, 1826. In the house of the commandant of the Peter and Paul Fortress, the judges announced the sentences to the Decembrists, who were brought from the casemates. After the verdict was announced, they were returned to their cells.

Meanwhile, the authorities were preoccupied with another problem. The absence for a long time of the practice of executions led to the fact that in St. Petersburg there were neither those who knew how to build a scaffold, nor those who knew how to carry out sentences.

On the eve of the execution, an experiment was conducted in the city prison, in which a hastily made scaffold was tested using eight-pound sandbags. The experiments were personally led by the new governor-general of St. Petersburg Pavel Vasilyevich Golenishchev-Kutuzov.

Considering the results satisfactory, the governor-general ordered the scaffold to be dismantled and taken to the Peter and Paul Fortress.

Part of the scaffold got lost along the way

The execution was scheduled in the crown work of the Peter and Paul Fortress at dawn on July 25, 1826. This dramatic act, which was supposed to put an end to the history of the Decembrist movement, turned out to be tragicomic.

As the head of the crown work of the Peter and Paul Fortress recalled Vasily Berkopf, one of the cabbies carrying parts of the gallows, managed to get lost in the dark and appeared on the spot with a significant delay.

From midnight in the Peter and Paul Fortress there was an execution over those of the convicts who escaped execution. They were taken out of the casemates, their uniforms were torn off and swords were broken over their heads as a sign of the so-called "civil execution", then they were dressed in prisoners' robes and sent back to the cells.

Meanwhile the chief of police Chikhachev with an escort of soldiers of the Pavlovsky Guards Regiment, he took five sentenced to death from the cells, after which he escorted them to the kronverk.

When they were brought to the place of execution, the suicide bombers saw how the carpenters, under the guidance of an engineer Matushkina in a hurry trying to collect the scaffold. The organizers of the execution were almost more nervous than the convicts - it seemed to them that the cart with part of the gallows had disappeared not just like that, but as a result of sabotage.

The five Decembrists were put on the grass, and for some time they discussed their fate with each other, noting that they were worthy of a "better death."

"We must pay the last debt"

Finally, they took off their uniforms, which they immediately burned. Instead, the condemned were put on long white shirts with bibs, on which the word “criminal” and the name of the convict were written.

After that, they were taken to one of the nearby buildings, where they had to wait for the completion of the scaffold. In the house of suicide bombers communed: four Orthodox - the priest Myslovsky, Lutheran Pestel - pastor rainboat.

Finally, the scaffold was completed. Those sentenced to death were again brought to the place of execution. The governor-general was present at the execution of the sentence. Golenishchev-Kutuzov, generals Chernyshev, Benkendorf, Dibich, Levashov, Durnovo, police chief Knyazhnin, police chiefs Posnikov, Chikhachev, Derschau, head of the kronverka Berkopf, archpriest Myslovsky, paramedic and doctor, architect Gurney, five assistant quarter overseers, two executioners and 12 Pavlovian soldiers under the command of a captain Polman.

Chief of Police Chikhachev read the verdict of the Supreme Court with the final words: "Hang for such atrocities!".

“Gentlemen! We must pay the last debt, ”Ryleev remarked, turning to his comrades. Archpriest Pyotr Myslovsky read a short prayer. White caps were thrown over the heads of the convicts, which caused them dissatisfaction: “What is this for?”

The execution turned into a sophisticated torture

Everything continued to go according to plan. One of the executioners suddenly collapsed into a swoon, and he had to be urgently carried away. Finally, a drum roll sounded, nooses were thrown around the necks of the executed, a bench was pulled out from under their feet, and after a few moments, three of the five hanged fell down.

According to Vasily Berkopf, the head of the crown work of the Peter and Paul Fortress, a hole was dug under the gallows, on which boards were laid. It was assumed that at the time of execution, the boards would be pulled out from under their feet. However, the gallows was built in a hurry, and it turned out that the suicide bombers standing on the boards did not reach the hinges with their necks.

They began to improvise again - in the destroyed building of the School of Merchant Navigation, they found benches for students, who were put on the scaffold.

But at the moment of execution, three ropes broke. Either the executioners did not take into account that they were hanging the sentenced with shackles, or the ropes were initially of poor quality, but three Decembrists - Ryleev, Kakhovsky and Muravyov-Apostol - fell into the pit, breaking through the boards with the weight of their own bodies.

Moreover, it turned out that the hanged Pestel reached the boards with his toes, as a result of which his agony stretched out for almost half an hour.

Some of the witnesses of what was happening became ill.

Muravyov-Apostol is credited with the words: “Poor Russia! And we don’t know how to hang decently!”

Perhaps this is just a legend, but we must admit that the words were very suitable at that moment.

Law versus tradition

The leaders of the execution sent messengers for new boards and ropes. The procedure was delayed - finding these things in St. Petersburg early in the morning was not such an easy task.

There was one more nuance - the military article of that time prescribed execution before death, but there was also an unspoken tradition according to which it was not supposed to repeat the execution, because it meant that "The Lord does not want the death of the condemned." This tradition, by the way, took place not only in Russia, but also in other European countries.

In this case, Nicholas I, who was in Tsarskoye Selo, could decide to stop the execution. From midnight, messengers were sent to him every half an hour to report on what was happening. Theoretically, the emperor could intervene in what was happening, but this did not happen.

As for the dignitaries who were present at the execution, it was necessary for them to bring the matter to the end, so as not to pay with their own careers. Nicholas I banned quartering as a barbaric procedure, but what happened in the end was no less barbaric.

Finally, new ropes and boards were brought in, the three who had fallen, who had been injured in the fall, were again dragged onto the scaffold and hung a second time, this time achieving their death.

Engineer Matushkin answered for everything

Engineer Matushkin was made the last for all the omissions, who was demoted to the soldiers for poor-quality construction of the scaffold.

When the doctors declared the death of the hanged, their bodies were removed from the gallows and placed in the destroyed building of the School of Merchant Navigation. By this time it was dawn in St. Petersburg, and it was impossible to take out the corpses for burial unnoticed.

According to Chief Police Officer Knyazhnin, the following night the bodies of the Decembrists were taken out of the Peter and Paul Fortress and buried in a mass grave, on which no sign was left.

There is no exact information about where exactly the executed were buried. The most likely place is Golodai Island, where state criminals have been buried since the time of Peter I. In 1926, on the 100th anniversary of the execution, Golodai Island was renamed the Decembrist Island, with a granite obelisk installed there.

The movement of revolutionaries, who were later called Decembrists, had its own ideology. It was formed under the influence of the liberation campaigns of the Russian army in the countries of Europe. Fighting with the Napoleonic army, the best representatives of the Russian officer corps got acquainted with the political life of other countries, which differed sharply from the regime that reigned in Russia.

Many representatives of the nobility and advanced intelligentsia who joined the opposition movement were also familiar with the writings of the French enlighteners. The ideas of the great thinkers were in tune with the thoughts of those who expressed dissatisfaction with the policy of the government of Alexander I. Many progressive oppositionists hatched plans to adopt a constitution.

The spearhead of the ideology of the opposition movement was directed against tsarism and serfdom, which became a brake on the progressive development of Russia. Gradually, a network of conspirators formed in the country, waiting for the right moment to start a speech. Such conditions arose in December 1825.

Decembrist revolt

After the death of Alexander I, there were no direct heirs to the throne. Two brothers of the emperor, Nicholas and Constantine, could claim the crown. The latter had more chances to ascend the throne, but Constantine was not going to become autocrat, because he was afraid of intrigues and palace coups. For a month of days, the brothers could not decide which of them would lead the country. As a result, Nikolai decided to take on the burden of power. The oath ceremony was to take place on the afternoon of December 14, 1825.

It was this day that the conspirators considered the most suitable for an armed uprising. The headquarters of the movement decided in the morning to advance troops sympathizing with the opposition to the Senate Square in St. Petersburg. The main forces of the rebels were supposed to prevent this from happening, other units at that time were going to capture the Winter Palace and arrest the imperial family. It was assumed that the fate of the king will decide the so-called Great Cathedral.

But the participants in the uprising were disappointed: Nikolai was sworn in ahead of schedule. The confused Decembrists did not know what to do. As a result, they lined up units subordinate to them on Senate Square around the monument to Peter I and repelled several attacks by troops supporting the tsar. And yet, by the evening of December 14, the uprising was crushed.

Nicholas I took all measures to roughly punish the Decembrists. Several thousand rebels were arrested. The organizers of the uprising were put on trial. Someone begged the king for forgiveness, but some Decembrists showed courage to the end. Five instigators of the rebellion were sentenced by the court to be hanged. Ryleev, Pestel, Bestuzhev-Ryumin, Muraviev-Apostol and Kakhovsky were executed in the summer of 1826 in the Peter and Paul Fortress. Many participants of the December performance were exiled to distant Siberia for many years.

The thing is that historically the Decembrists in Russia were the first who dared to oppose the power of the tsar. It is interesting that the rebels themselves began to study this phenomenon, they analyzed the reasons for the uprising on Senate Square and its defeat. As a result of the execution of the Decembrists, Russian society lost the very color of enlightened youth, because they came from families of the nobility, glorious participants in the war of 1812.

Who are the Decembrists

Who are the Decembrists? Briefly, they can be characterized as follows: they are members of several political societies fighting for the abolition of serfdom and the change of state power. In December 1825, they organized an uprising, which was brutally suppressed. 5 people (leaders) were put to shameful execution for officers. Decembrists-participants were exiled to Siberia, some were shot in the Peter and Paul Fortress.

Causes of the uprising

Why did the Decembrists revolt? There are several reasons for this. The main one, which they all, as one, reproduced during interrogations in the Peter and Paul Fortress - the spirit of free thinking, faith in the strength of the Russian people, tired of oppression - all this was born after the brilliant victory over Napoleon.

It is no coincidence that 115 people from among the Decembrists were participants in the Patriotic War of 1812.

After all, during military campaigns, liberating European countries, they never encountered the barbarity of serfdom. This forced them to reconsider the attitude of "slaves and masters" towards their country.

It was obvious that serfdom had become obsolete. Fighting side by side with the common people, communicating with them, the future Decembrists came to the conclusion that people deserve a better fate than a slave existence. The peasants also hoped that after the war their situation would change for the better, because they shed blood for the sake of their homeland. But, unfortunately, the emperor and most of the nobles firmly held on to the serfs. That is why from 1814 to 1820 more than two hundred peasant uprisings broke out in the country.

The apotheosis was the rebellion against Colonel Schwartz of the Semyonovsky Guards Regiment in 1820. His cruelty to ordinary soldiers crossed all boundaries. Activists of the Decembrist movement, Sergei Muravyov-Apostol and Mikhail Bestuzhev-Ryumin, witnessed these events, as they served in this regiment. It should also be noted that a certain spirit of freethinking was instilled in most of the participants by the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum: for example, I. Pushchin and V. Kuchelbeker were its graduates, and A. Pushkin's freedom-loving poems were used as inspirational ideas.

Southern Society of Decembrists

It should be understood that the Decembrist movement did not arise out of nowhere: it grew out of world revolutionary ideas. Pavel Pestel wrote that such thoughts go “from one end of Europe to Russia”, even covering Turkey and England, which are opposite in mentality.

The ideas of Decembrism were realized through the work of secret societies. The first of them are the Union of Salvation (Petersburg, 1816) and the Union of Welfare (1818). The second arose on the basis of the first, was less conspiratorial and included a larger number of members. In 1820, it was also dissolved due to differences of opinion.

In 1821, a new organization appeared, consisting of two Societies: Northern (in St. Petersburg, headed by Nikita Muravyov) and Southern (in Kiev, headed by Pavel Pestel). Southern society had more reactionary views: in order to establish a republic, they proposed to kill the king. The structure of the Southern Society consisted of three departments: the first, along with P. Pestel, was headed by A. Yushnevsky, the second - by S. Muravyov-Apostol, the third - by V. Davydov and S. Volkonsky.

Decembrist leaders:

1. Pavel Ivanovich Pestel

The leader of the Southern Society, Pavel Ivanovich Pestel, was born in 1793 in Moscow. He receives an excellent education in Europe, and upon his return to Russia begins service in the Corps of Pages - especially privileged among the nobles. The pages are personally acquainted with all members of the imperial family. Here, for the first time, the freedom-loving views of the young Pestel are manifested. Having brilliantly graduated from the Corps, he continues to serve in the Lithuanian regiment with the rank of ensign of the Life Guards.

Pavel Pestel

Pavel Pestel During the war of 1812, Pestel was seriously wounded. Having recovered, he returns to the service, bravely fights. By the end of the war, Pestel had many high awards, including golden award weapons. After World War II, he was transferred to serve in the Cavalier Guard Regiment - at that time the most prestigious place of service.

While in St. Petersburg, Pestel learns about a certain secret society (the Union of Salvation) and soon joins it. Pavel's revolutionary life begins. In 1821, he headed the Southern Society - in this he was helped by magnificent eloquence, a wonderful mind and the gift of persuasion. Thanks to these qualities, in due time he achieves unity of views of the Southern and Northern societies.

Pestel's constitution

In 1823, the program of the Southern Society, drawn up by Pavel Pestel, was adopted. It was unanimously accepted by all members of the association - the future Decembrists. Briefly, it contained the following points:

- Russia should become a republic, united and indivisible, consisting of 10 districts. State administration will be carried out by the People's Council (legislative) and the State Duma (executive).

- In resolving the issue of serfdom, Pestel proposed to immediately abolish it, dividing the land into two parts: for the peasants and for the landowners. It was assumed that the latter would rent it out for farming. Researchers believe that if the reform of 1861 to abolish serfdom went according to Pestel's plan, then the country would very soon embark on a bourgeois, economically progressive path of development.

- The abolition of the institution of estates. All the people of the country are called citizens, they are equally equal before the law. Personal freedoms and inviolability of the person and home were declared.

- Tsarism was categorically not accepted by Pestel, so he demanded the physical destruction of the entire royal family.

Russkaya Pravda was supposed to come into force as soon as the uprising was over. It will be the basic law of the land.

Northern Society of Decembrists

The northern society begins to exist in 1821, in the spring. Initially, it consisted of two groups, which later united. It should be noted that the first group was more radical, its members shared the views of Pestel and fully accepted his "Russian Truth".

The activists of the Northern Society were Nikita Muravyov (leader), Kondraty Ryleyev (deputy), princes Obolensky and Trubetskoy. Ivan Pushchin played an important role in the Society.

The Northern Society operated mainly in St. Petersburg, but it also had a branch in Moscow.

The path of unification of the Northern and Southern societies was long and very painful. They had cardinal differences on some issues. However, at the convention in 1824, it was decided to begin the process of unification in 1826. The uprising in December 1825 destroyed these plans.

2. Nikita Mikhailovich Muravyov

Nikita Mikhailovich Muravyov comes from a noble family. Born in 1795 in St. Petersburg. He received an excellent education in Moscow. The war of 1812 found him in the rank of collegiate registrar at the Ministry of Justice. He runs away from home for the war, making a brilliant career during the battles.

Nikita Muraviev

Nikita Muraviev After World War II, he began to work as part of secret societies: the Union of Salvation and the Union of Welfare. In addition, writes the charter for the latter. He believes that a republican form of government should be established in the country, only a military coup can help this. During a trip to the south, he meets P. Pestel. Nevertheless, it organizes its own structure - the Northern Society, but does not break ties with a like-minded person, but, on the contrary, actively cooperates.

He writes the first version of his version of the Constitution in 1821, but it did not find a response from other members of the Societies. A little later, he will reconsider his views and release a new program offered by the Northern Society.

Muraviev's constitution

The constitution of N. Muravyov included the following positions:

- Russia should become a constitutional monarchy: the legislative power is the Supreme Duma, consisting of two chambers; executive - the emperor (concurrently - the supreme commander). Separately, it was stipulated that he did not have the right to start and end the war on his own. After a maximum of three readings, the emperor had to sign the law. He had no right to impose a veto, he could only delay the signing in time.

- With the abolition of serfdom, the lands of the landowners should be left to the owners, and to the peasants - their plots, plus 2 acres to each house.

- The right to vote is limited to landowners. Women, nomads and non-owners were kept away from him.

- Abolish the institution of estates, equalize everyone with one name: citizen. The judicial system is the same for everyone. Muraviev was aware that his version of the constitution would meet fierce resistance, so he provided for its introduction with the use of weapons.

Preparations for the uprising

The secret societies described above lasted 10 years, after which the uprising began. It should be said that the decision to revolt arose quite spontaneously.

While in Taganrog, Alexander I dies. Due to the lack of heirs, the next emperor was to be Constantine, Alexander's brother. The problem was that he secretly abdicated at one time. Accordingly, the board passed to the youngest brother, Nikolai. The people were in confusion, not knowing about the renunciation. However, Nicholas decides to take the oath on December 14, 1825.

Nicholas I

Nicholas I The death of Alexander became the starting point for the rebels. They understand that it is time to act, despite the fundamental differences between the Southern and Northern societies. They were well aware that they had catastrophically little time to prepare well for the uprising, but they believed that it was criminal to miss such a moment. This is exactly what Ivan Pushchin wrote to his lyceum friend Alexander Pushkin.

Gathered on the night before December 14, the rebels prepare a plan of action. It boiled down to the following points:

- Appoint Prince Trubetskoy as commander.

- Occupy the Winter Palace and the Peter and Paul Fortress. A. Yakubovich and A. Bulatov were appointed responsible for this.

- Lieutenant P. Kakhovsky was supposed to kill Nikolai. This action was supposed to be a signal to action for the rebels.

- Carry out propaganda work among the soldiers and win them over to the side of the rebels.

- To convince the Senate to swear allegiance to the emperor was assigned to Kondraty Ryleev and Ivan Pushchin.

Unfortunately, not everything was thought out by the future Decembrists. History says that traitors from among them made a denunciation of the impending rebellion to Nicholas, which finally convinced him to appoint an oath to the Senate in the early morning of December 14th.

The uprising: how did it go

The uprising did not go according to the scenario that the rebels had planned. The Senate manages to swear allegiance to the emperor even before the campaign.

However, regiments of soldiers are lined up in battle formation on Senate Square, everyone is waiting for decisive action from the leadership. Ivan Pushchin and Kondraty Ryleev arrive there and assure them of the imminent arrival of the command, Prince Trubetskoy. The latter, having betrayed the rebels, sat out in the tsarist General Staff. He failed to take the decisive action that was required of him. As a result, the uprising was crushed.

Arrests and trial

In St. Petersburg, the first arrests and executions of the Decembrists began to take place.

An interesting fact is that it was not the Senate, as it was supposed to, but the Supreme Court specially organized by Nicholas I for this case, who did not deal with the trial of the arrested.

The fact is that shortly before the uprising, he accepted A. Mayboroda as a member of the Southern Society, who turned out to be a traitor. Pestel is arrested in Tulchin and taken to the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg.

Mayboroda also wrote a denunciation of N. Muravyov, who was arrested in his own estate.

579 people were under investigation. 120 of them were exiled to hard labor in Siberia (among them, Nikita Muravyov), all were shamefully demoted to military ranks. Five rebels were sentenced to death.

execution

Addressing the court about a possible way to execute the Decembrists, Nikolai notes that blood should not be shed. Thus, they, the heroes of the Patriotic War, are sentenced to the shameful gallows ...

Who were the executed Decembrists? Their surnames are as follows: Pavel Pestel, Pyotr Kakhovsky, Kondraty Ryleev, Sergei Muravyov-Apostol, Mikhail Bestuzhev-Ryumin. The verdict was read out on July 12, and they were hanged on July 25, 1826. The place of execution of the Decembrists was equipped for a long time: a gallows with a special mechanism was built. However, it was not without overlays: three convicts fell off their hinges, they had to be hung again.

In the place in the Peter and Paul Fortress where the Decembrists were executed, there is now a monument, which is an obelisk and a granite composition. It symbolizes the courage with which the executed Decembrists fought for their ideals.

Peter and Paul Fortress, St. Petersburg

Peter and Paul Fortress, St. Petersburg