Conversational Latin lessons. How to learn Latin on your own

Theme two. Latin verb (verbum) in the present tense (presens)

Theme four. Past tense imperfective (imperfectum) or simple past

Topic six. Nouns of the third, fourth and fifth declensions

Topic seven. Past perfect tense (Perfectum)

Topic eight. Participle and verbal noun

Theme nine. Declension and degrees of comparison of adjectives and adverbs (nomina adiectiva et proverbia)

Topic ten. Subjunctive (coniunctivus)

Topic Eleven. Name numeral, Roman chronology and calendar

Topic twelve. Irregular Verbs

Topic thirteen. More complex phenomena of Latin syntax (subordinate clauses, infinitive and independent constructions)

Topic fourteen. Latin versification

TEXTS TO READ

GRAMMAR REFERENCE

LATIN-RUSSIAN DICTIONARY

RUSSIAN-LATIN DICTIONARY

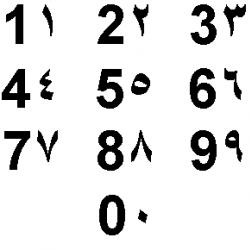

c (before e, i, y, ae, oe), k (in other cases)

to (used only in the word Kalendae)

in combination qu - sq

c (z between vowels)

and (in words of Greek origin)

Note. The combination ngu is read [ngv] (or [ngu], before a vowel); ti is read as [qi] before a vowel, [ti] before a consonant; two-vowel ae and oe are read as [e], two-vowel au and eu are read in one syllable (with non-syllable y: [ay], [eu]).

Accent rules. Latin syllables are short or long (longitude and shortness of vowels are usually noted in dictionaries). In addition, closed syllables are considered long. For example, in the word documentum, the syllable men is closed because its vowel is followed by two consonants. Open syllables, in turn, are always short. For example, in the word ratio, the syllable ti is short because it is open, that is, its vowel is followed by the vowel i. A syllable followed by a single consonant, for example, the syllable bi in the word mobilis, is also considered open, and therefore short. stress in Latin words ah is put in a regular way. It stands on the penultimate syllable, or on the third from the end, if the penultimate one is short, i.e., the stress, figuratively speaking, tends to the middle of the word and is never placed on the last syllable (except, of course, when the word consists of one syllable ).

Theme one. noun

The Latin noun, like the Russian one, declines according to cases, but the number of cases and their functions in the Latin language are somewhat different from Russian. Latin nouns are divided into five types of declension, which we will consider in turn. Now let's start with the two simplest and most regular types of declension - the first and second.

The practical signs of these declensions are: the ending -a in the nominative and -ae in the genitive singular for the first declension, and the endings -us, -er, -um in the nominative and -i in the genitive for the second declension.

Thus, the first declension includes nouns with a base on -a. For example, culpa, culpae (wine). They are mostly feminine, with the exception of a few masculine nouns denoting professions, for example, poeta, poetae (poet), nauta, nautae (sailor), agricola, agricolae (farmer).

The second declension is more complex and includes masculine and neuter names. At the same time, nouns ending in -um belong to the middle gender. As a general rule (for all declensions), the nominative, accusative and vocative cases of neuter gender names always coincide, and in the plural they always end in -a. For names in -us of the second declension - the only time in the whole system of the Latin declension - the vocative does not coincide with the nominative: meus amicus verus, my faithful friend, but - mi amice vere, my faithful friend! Most names in -us end in -e in the vocative case, with a few exceptions - nulla regula sine exceptionibus: proper names in -ius, such as Publius - Publi, as well as the pronoun meus and the noun filius in the vocative case end in -i: meus -mi, filius-fili.

The dative case in the plural always coincides with the deferred (ablativus is a deferred case, which can mean separation, instrument of action, place and time and is translated into Russian using various cases).

We decline, for example, such nouns: familia, ae, f (family), locus, i m (place), ager, i m (field), damnum, i n (damage).

The only thing

plural

The only thing

plural

The only thing

plural

The only thing

plural

Fill in the rest of the cells yourself!

Nota bene: Words must agree in gender, number, and case in order to make sense. Don't forget also that nouns and adjectives of the second declension in -er have an alternation in declension, e.g. (exemple gratia): nom. ager, gen. agriculture, etc. (et cetera). Except - what is the Latin for "There are no rules without exceptions"? - a few adjectives to remember:

liber, liberi; miser, miseri; asper, asperi; tener, teneri.

Latin prepositions are used with two cases - accusative and deductive, and most of them agree with one or another case, with the exception of the prepositions in (in, on) and sub (under). For example, in silva (in the forest), in silvam (into the forest). For a list of prepositions, see the grammar reference.

Now decline these phrases:

tua prima cura magna, poeta clarus, meus et noster amicus verus, bellum domesticum, collega bonus, nauta miser, agricola liber, tutela legitima, titulus iustus, culpa lata, causa privata, dolus malus, edictum perpetuum, iustae nuptiae, aeterna historia, terra incognita, persona suspecta, pia desideria.

Translate and memorize.

Ad gloriam. Ab hoc et ab hac. Ab origin. Lapsus calami. Lapsus linguae. Nomina sunt odiosa. Non multa, sed multum. Perse. Sineira et studio. status quo. Ultima ratio. Ex iusta causa. Ex aequo et bono. ad hoc. Ad memorandum. ad usum. Ex libris. In aeternum. Ubi bene, ibi patria. Sine loco, anno vel nomine. Ante Christum natum. Anna Domini. Vide supra. In dubio pro reo. Sine case. Ex delicto. Contra tabulas. Pro form. Curriculum vitae. cum deo. Ex cathedra. Nemo est iudex in propria causa. Non est philosophia populare artificium. Via antiqua est via tuta.

N.B. If you forgot something, you can find the declension table for nouns, adjectives and pronouns in the grammar reference at the end of your textbook. In the dictionary, you can find the meaning of unfamiliar Latin words.

Theme two. Latin verb (verbum)

in the present tense

There are four types of Latin conjugation. The first conjugation includes verbs with a stem ending in -a, the second - with a stem ending in -e, the third - with a stem ending in -i, and the fourth - with a stem ending in -i. Verbs of the third conjugation ending in a consonant need a connecting (so-called thematic) vowel.

Verbs of the third conjugation add a connecting vowel to the stem

i in all other cases

N.B. You can find the verb conjugation table in the grammar guide.

Verbs can be used in different tenses, voices and moods. Let's start with the simplest - the present indicative mood. It is formed quite simply: personal endings of the active or passive voice are added to the stem of the verb (do not forget about the connecting vowel), which should be remembered:

active voice

passive voice

With this in mind, you can say anything in Latin. Don't believe? Try it! How to say, for example, take, grab? - capere, if you forgot, then look in the dictionary. How do you say I'm getting a cat? - Felem capio. Oh, I'm being enslaved! - Probably, the cat thinks, or: O, heu, in servitutem capior! - if it is a Roman cat - and tries to run away. But hiding from you is not so easy. As a result, the cat is taken - capta est. But how do you say, "I grabbed the cat"? You don't know this yet. Although, probably, someone already knows, if out of curiosity he looked at one of the subsequent lessons of the textbook.

We have just met four forms of the verb to take, to grab. Find them: capio - capta - capĕre - capior.

Capĕre is the indefinite form (of the third, as you know, conjugation) of the verb to take.

Capio is the first person of the present tense, I take. Accordingly, capis, capit, capimus, capitis, capiunt - you take, he or she takes, we take, you take, they take.

Capta is the passive past participle. Here it is feminine (because we are talking about the cat). Full form: captus, capta, captum - taken, taken, taken.

Now if you look in the dictionary, you will find that all the verbs are given there approximately in this form: capio, cepi, captum, capĕre. We know all these forms, except for the second, which expresses the completed action and which will be discussed below.

Finally, capior is the present tense form of the passive voice. Let me remind you: they will take you caperis, they will take him or her - capitur, they will take us - capimur, they will take you - capimini, they will be taken - capiuntur.

The imperative mood is formed very simply:

First, you find the stem of the verb, with the thematic vowel, if it is the third conjugation (i.e., what remains if the -re ending is dropped from the indefinite form), for example: cape/re. Then, if you want to say to your dog: GET IT! – the problem has already been solved, since CAPE! and will mean an indication to take. If you have a whole bunch, then use another one instead of the -e ending, -TE (with a thematic vowel), and you get CAPITE!, which means CAP, GRAB!

If, on the contrary, you need to say FU, DON'T (or DARE) GRAB! you say NOLI (NOLITE) CAPERE!

The verb esse to be, as one would expect, is declined in a not quite regular way: sum, es, est, sumus, estis, sunt (I am, you are, he is, etc.).

Translate now and memorize a few expressions! In what forms are the verbs used here?

Noli accusare! Mitty! Es! Este! Noli esse captus! Nec tecum vivere possum, nec sine te. Rogo te, Luci Titi, petoque ad te! Credit mihi. Non creditus tibi. Isti libri tibi a me mittuntur. Noli dicere, si tacere debis. Divide et impera. Noli dicere quod nescis. Cognosce te ipsum. Da mihi veniam, si erro. Ne varietur. Probatum est. Ira non excusat delictum. Tantum scimus, quantum memoria tenemus. Commodium ex iniuria sua nemo habere debet. Credo. Veto. Absolvo. Condemno. In dubio abstine. non licet. Dare, facere, praestare. Respondere, cavere, agere.

I think you can now easily translate the following texts. Read and identify the basic forms of nouns and verbs found in the text. The nouns you will see (with the exception of mulier) belong to the first two declensions.

To facilitate translation, the texts of the first few sections are accompanied by a small glossary. When translating other texts, the meaning of unfamiliar Latin words must be checked using a dictionary. The length and shortness of vowels, which you need to know for the correct pronunciation of words, also check in the dictionary.

Puĕri Romāni cum paedagōgis in scholam propĕrant. Paedagōgi viri docti, sed servi erant.

Puellae domi manent et mater eas domi laborāre, coquere, sed etiam cantāre, saltare, legere, scribere et recitare docet. Multae matrōnae et mulieres Romānae doctae erant.

Puĕros magister in schola legĕre, scribĕre et recitāre docet. Magister librum alphabet, puĕri tabŭlas et stilos tenent. Puĕri in tabŭlis sententias scribunt, deinde recǐtant.

Magister bonus pulchre recǐtare potest, puĕri libenter audiunt; magister malus male recǐtat: pueri dormiunt. Sed magister virgam habet et puĕras verbĕrat. Orbilium, Horatii poetae clari magistrum, sevērum esse dicunt. Ita Horatius Orbilium per iocum "plagōsum" dicit, nam saepe puĕris plagas dat. Discipŭli magistri verba memoriā tenent: "Discite, pueri! Non scholae, sed vitae discǐmus."

domi - at home

stilus, i - writing stick, style

teneo, tenui, tentum, tenēre - to keep

coquo, coxi, coctum, cocere - cook, cook

mulier, mulieris, f. - woman

virga, ae, f. - rod, rod

verbĕro, verberavi, verberatum, verberāre - to beat

iocus, i - joke

plaga, ae - blow

De servis Romanrum

Latium in Italy est. Incŏlae Latii Latīni erant. Latium patria linguae Latinae erat. Multae et pulchrae villae virōrum Romanōrum in Italia erant.

Romani magnum numerum servrum habent. Familia romana ex dominis, liberis et servis constat. Servos Romani bellis sibi parant. Servi liberi non sunt, etiam filii servōrum servi esse debent. In villa opulenti viri multi servi laborant. Multi domini severi sunt, servos saepe vituperant et puniunt. Servi severos dominos non amant, sed timent. Recte etiam dictum est, inter dominum et servum nulla amicitia est. Cato, orator Romanōrum clarus, legere solet: Servus instrumentum vivum est.

Sed Graeci viri docti, qui servi Romanōrum erant, non in agri vel latifundiis laborāre debent. Multi servi docti paedagōgi, servi a libellis, bibliothecarii, librarii et etiam vestiplici vestiplicaeque et ornartrices erant. Alii servi Graeci morbos curant, alii liberos Romanôrum educant et pueros grammaticam, philosophiam, litteras docent. Magistri Graeci de claris poetis Graecōrum, ut de Homēro et Hesiōdo, et de philosophis, ut de Platone et Democrito et Pythagore et aliis viris doctis narrant. Liberi libros poetārum Graecōrum amant et saepe tragoedias et comoedias clarōrum poetārum legunt.

vitupero, -are, 1

soleo, solitus sum, solere, 2

servus a libellis

ornartrix, icis f

was, were

consist

deliver, obtain

to be in the habit

copyist of books

a slave or slave who looked after the clothes of their masters

hairdresser slave

Theme three. Features of Latin syntax (simple sentence, adjective and predicate place, passive constructions, cases, prepositions, etc.)

The construction of the Latin sentence differs from the Russian in some features. In order to read and write Latin without errors, you need to remember a few simple rules.

First of all, the verb-predicate, as a rule, is at the very end of even a very long sentence. Always look for it there! The subject, as a rule, is at the beginning or closer to the beginning. In order to be convinced of this, please look again at the texts that we have already read.

Further, personal pronouns are rarely used in Latin, so a sentence can only consist of one word: lego means I speak. So be careful (audire debetis). If the verb-predicate is in the first or second person, do not look for the subject. He is not. If the verb is in the third person, then most likely you will find the subject in the form of a noun in the nominative case, but if it is not there, then use the third person pronoun.

Adjectives and pronouns are placed (as in French) after the noun they refer to: amicus meus, vir doctus.

Very many things can be expressed in Latin remarkably concisely. It is no coincidence that Latin maxims are so famous. True, the Russian language is almost as good as Latin. For example, a wedge is knocked out by a wedge - clavus clavo pellitur, or a camp fortified with a rampart - castra vallo munitur. Try saying it in German or English. The examples given are the so-called passive turnover. The instrument of action (wedge, shaft) is used here in the deferred case (ablative) without a preposition. The character is also used in the ablative, instrumental case (which corresponds here to the Russian creative), but with the preposition -a / -ab: castra a militibus vallo munitur the camp is fortified by soldiers with a rampart.

A very interesting phenomenon of Latin syntax is the so-called double accusative case. We have already met with this turnover. Remember?

Ita Horatius Orbilium per iocum "plagosum" dicit -

Horace jokingly calls Orbilius pugnacious.

Such a turnover is used with verbs with the meaning to name (apello, voco, dico, nomino), to appoint, to elect (creo, facio, eligo), to consider someone by someone (puto, habeo, duco, existimo).

The double nominative case is used with passive verbs. Compare:

Praedium rusticum fundum apellamus.

A piece of land is called a fundum (double accusative).

Praedium rusticum fundus appellatur.

The land plot is called fundum (double nominative).

Latin prepositions are used with only two cases - accusative and deferred. You will remember that the prepositions in in, super over and sub under are used with the accusative case when they mean the movement "in", "above" or "under", while the positive case indicates the location: in silvam propero, I go to forest, in silva est, is in the forest, sub aquam, under water, sub aqua, under water. (However, in Russian they are used in the same way.) If you now look at the list of prepositions in the grammar reference, you will see that this is a more or less general rule: prepositions that mean movement or spatial arrangement are usually (though not always) used with the accusative case, and the rest with the deferred.

Translate and memorize.

Culpa lata dolo malo aequiparatur. Incertae personae legatum inutiliter relinquitur. Nemo punitur pro alieno delicto. Invito benefitium non datur. Nemo debet bis punier pro uno delicto. Iniuria non praesumitur. Imperitia culpae adnumeratur. Negative non probantur. Consilia multorum requiruntur in magnis. Victoria concordia gignitur. Asinus asinorum in saecula saeculorum. Cum servis nullum est conubium. Arbitrium est iudicium boni viri secundum aequum et bonum. Circulus vitiosus.

Today's task will be more difficult for you. Please try to translate into Latin using the texts from the previous lessons (for now, translate the past tense into the present).

We know that Roman boys went to school and girls at home. Children at school were taught to read, write, and recite. Many teachers were Greeks, so they told (translate: tell) them about their homeland and about famous Greek poets and philosophers. The children must obey the teacher. They listen to a good mentor with pleasure. “Do you know the famous Greek philosophers, children?” the teacher asks. “We know,” replies Mark, “for example, Pythagoras and Democritus were Greek sages (sapiens, nom. plur. sapientes), but Plato was the greatest (maximus) philosopher.” “And you, Peter, do you know that your name (nomen) is Greek?” - "Yes I know. The Greek word Petros means stone (lapis). "That's right, my boy!"

Theme four. Past tense imperfective

species (imperfectum) or simple past

The simple past tense is formed really simply. The suffix -bā- is added to the stem of the verb, and the personal endings (active or passive voice) remain the same, except for the first person of the active voice, where the ending -o becomes -m. For example: amo (I love) - ama-ba-m (loved), ama-ba-s, ama-ba-t, etc. and, accordingly, amor (I am loved) - ama-ba-r (I was loved), ama-ba-ris, ama-ba-tur, etc. In the third and fourth declension, the connecting vowel will be -e-: scrib-e-ba-m, dormi-e-ba-m.

Now let's practice a little.

Please rewrite the De servis Romanorum we read in the simple past tense. In addition, this is completely logical, because there are no more slaves or ancient Rome. Now do the same with the text you translated last time about the Roman school. Bene!

Read the text about ancient Greek and Roman gods and goddesses.

Graeci et Romani multos deos et multas deas colebant et apud aras et in templis eis sacrificabant. Dei deaeque in Olympo sed etiam in templis habitare putabantur.

In Foro Romano rotundum templum Vestae deae erat, ubi Virgines Vestales ignem perpetuum custodiebant; non procul Atrium Vestae erat, ubi Virgines Vestales habitabant.

Primus in numero deorum et maximus Iuppiter, filius Saturni et Rheae esse nominantur. Locus, ubi Iuppiter sedebat et mundi imperium tenebat, Olympius altus esse putantur. Inde deus deorum, dominus caeli et mundi, tonabat et fulminabat: equi rapidi dei per totum mundum volabant. Uxor dei maximi Iuno, dea nuptiarum, erat. Secundus Saturni filius Neptunus deus oceani erat. Neptunus et uxor eius Amphitrite oceanum regnabant. Si deus aquarum per undas equis suis procedebat, mare tranquillum erat, si autem ira commotus tridente aquas dividiebat, oceanus magnus fluctuabat. Saturnis tertius filius Pluto, horridus dominus umbrarum, deus inferorum, et uxor eius Proserpina dea agriculturae sub terra habitabant. Iuppiter multos liberos habebat. Minerva dea sapientiae et belli erat; Diana dea silvarum, preterea dea lunae erat. Apollo, frater Dianae, deus artis et scientiarum, patronus poetarum, et Venus dea pulchra et preaclara amoris erant. Mars deus pugnarum, dum Bacchus laetus deus vini et uvarum erant. Inter arma tacent Musae.

fulmen, fulminis

- altar, altar

- to sacrifice

- Vesta, goddess of the hearth, as well as the patroness of public life

Vestal virgin, priestess of the goddess Vesta. Vestals lived in a special house next to the temple and kept a vow of chastity

- Eternal flame

- thunder

- throw lightning

- lightning

- fly

- protrude

- driven

- trident

- worry

Theme five. Future tense (futurum I)

The so-called first future tense for verbs of the first and second conjugations is formed using the suffix -b-. Verbs of the third and fourth conjugations in the future tense have the suffix -a- in the first person and -ē- in the rest. It is convenient to present this in the form of a table:

I and II conjugations

III and IV conjugations

Read:

In ludo litterario

"Publi, cur hodie in schola non eras?" - magister puerum rogat. At Publius: "Aeger eram, - inquit, - in schola adesse non poteram". "O te miserum! Erat-ne medicus apud te?" "Medicus me visitabat et mater medicinam asperam mihi dabat". "O te miserum! Sed responde, non-ne in Campo Martio heri eras et cum pueris pila ludebas?" Publius tacet, sed mox: "Queso, - inquit, - magister, medici verba audi: pila animum recreat et corpus confirmat. Ego praeceptis medici obtemperabam." Sed magister verbam Publi fidem non dat et: "Heri, – inquit, – tu pila animum recreabas, et ego hodie baculo corpus tibi confirmabo". Pueri a ludo domum currunt. Deinde in Campum Martium current, sed Publius domi manebit, nam medicina magistri aspera erat.

Pueri in Campo Martio non solum pila ludent, sed etiam current, salient et discum iacient. Viri Romani filios Athenas mittere solebant. Adulescentes in Graecia philosophiae studebant, verba clarorum oratorum audiebant, preclara aedifitia spectabant. Adulescentes Romani multos amicos in Graecia habebant. Marci amicus Athenis Romam venit, et cum Marco Romam visitat. Marcus amico Campum Martium monstrat et: "Est-ne, - inquit, - Athenis campus, ubi pila ludere et discum iacere potestis?" Et adulescens Graecus: "Athenis gymnasium et palaestram habemus, ubi viri et pueri cotidie corpora ludis gymnicis exercent".

Ludus litterarius=schola

sed: iaceo, iacere

Athenas, Athenis, etc.

- Oh, poor! Note that the pronoun and adjective are in the accusative case.

- soon, soon

- cane, staff

- throw, throw

but: lie down

- In Athens, in Athens

When answering the question where? (quo?) city names are used in the accusative case without a preposition, while the suspensive case indicates movement from? (unde?) or finding where? (ubi?)

We can not only read and write Latin, but also speak. You can, for example, talk to each other, talk about your educational institution about what you are interested in, what you are studying. You can tell about where you have been and what you have seen in other cities and countries, as well as about your plans. Finally, you can just say salvete! Let's start compiling our vade-mecum, a Latin phrase book.

The following words and expressions will help you talk about your city and school:

magnificus, a,um

monument

located

street, path

fabulous

structure

in charta monstrare, spectare

Russia nominatur

finitimus, a,um

chartam, epistulam

show on the map

our country

republic

called Russia

neighboring

famous

have you been...?

tell

visit

next year

postcard,

send

Berolinum (Berlin)

Lipsia, ae (Leipzig)

Lutetia Parisiorum; Parisii

Vindobona, ae (Vienna)

Helvetia, ae (Switzerland)

orientalis, is (eastern)

occidentalis, is (Western)

You will probably find a few everyday expressions useful when speaking:

Quis narrare, respondere etc. ... potest?

Hello! Hello!

right

Be healthy! Be healthy!

I apologize!

I give thanks, thank you

-How are you?

- Okay, I'm alive and well.

so please, okay (introductory word)

once upon a time

Who can tell, answer...?

Why...?

What are you doing? What are you doing?

Could you...?

Quis vestrum, quaeso, de terris et oppidis nobis narrare potest?

De schola narrate! Quid in ludo et post horam ludorum plerumque agetis?

Topic six. nouns of the third,

fourth and fifth declensions

You know the first and second declensions of nouns and adjectives. I think you will be interested to know how all the other names are declined. Let's start in order.

third declension

This declension includes nouns and adjectives of all three genders, while the endings of masculine and feminine genders always coincide, so we will distinguish between the forms of masculine-feminine and neuter genders separately.

Instruction

Learning Latin should begin with learning the alphabet. There are 25 letters in the Latin alphabet. The six letters (a, e, i, o, u, y) represent the 12 vowels of Latin. There are also 4 diphthongs in Latin. You need to know that in Latin there are long and short vowels. Shortness and longitude are denoted by superscripts: ā - "a" long, ă - "a" short. The stress in Latin words is never placed on the last syllable. In two-syllable words, the stress is placed on the initial syllable. In trisyllabic and polysyllabic words, the stress is placed on the second syllable from the end, if this second syllable is long. On the third syllable from the end, the stress is placed if the second syllable is short. For example, in the word transformatio, the emphasis is on "a".

Further, there are 4 verbal conjugations in Latin. In verbs of the first conjugation, the stem ends with a long (ā). For example, "ornāre", in which "ornā" is the stem and "re" is the suffix. The suffix can also be "ere". The second conjugation includes verbs whose stem ends in long "e" (ē), for example, "habēre". The third conjugation includes verbs whose stem ends in a consonant, short u, and short i (ŭ and ĭ), such as tangere (stem tang). The fourth conjugation includes long "i" verbs (ī), for example, "audīre", where "audī" is the stem and "re" is the suffix.

Verbs in Latin have the following grammatical categories: tense (six tenses: present tense, future first, future second, imperfect, perfect, pluperfect), mood (indicative, subjunctive and imperative), voice (real and passive), number (singular and plural), person (1st, 2nd and 3rd person). Of course, you need to study each section gradually. However, you should start somewhere, for example, let's study the four correct conjugations first. Let's consider how the verbs of I-IV conjugations change in the present tense of the indicative mood of the active voice.

Verb I of conjugation ornāre: orno, ornas, ornat, ornāmus, ornatis, ornānt. Verb II of conjugation tacēre: taceo, taces, tacet, tacēmus, tacētis, tacent. Verb III of conjugation tangere: tango, tangĭs, tangĭt, tangĭmus, tangĭtis, tangŭnt. Verb IV of conjugation audīre: audio, audis, audit, audīmus, audītis, audiuŭt.

Let's talk a little about nouns in Latin. They have the category of gender (male, female, neuter), number (singular, plural). There are 6 cases in Latin: Nominativus (nominative), Genetivus (genitive), Dativus (dative), Accusativus (accusative), Ablativus (positive), Vocativus (vocative). Nouns in Latin have 5 declensions. The first includes nouns with stems in ā and ă. To the second - on ŏ and ĕ. To the third - into a consonant and ĭ. K IV - on ŭ. By the fifth - on ē.

4th ed. - M.: 2009. - 352 p.

The textbook contains: grammar material for the program, designed for 120 hours of study time, and exercises for its assimilation; texts by Latin authors; Latin-Russian dictionary, including the vocabulary of textbook texts. In connection with the specifics of self-study, the book contains tests, guidelines and comments on texts. The selection of texts meets the interests of a wide range of readers.

For students of humanitarian faculties.

Format: djvu

The size: 2.5Mb

Download: drive.google

Format: pdf

The size: 31.4Mb

Download: drive.google

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction. Latin meaning 3

How the tutorial is built and what it teaches 8

What is Grammar 10

I part

I chapter 11

§ 1. Letters and their pronunciation (11). § 2. Combinations of vowels (13).

§ 3. Combinations of consonants (14). § 4. Longitude and shortness of vowels (number) (14). §5. Accent (15). Exercises (15).

II chapter 16

§ 6. Characteristics of the structure of the Latin language (16). § 7. Initial information about the noun (18). § 8.1 declination (20). § 9. The verb esse (to be) (22). § 10. Some syntactic remarks (22). Exercises (23).

III chapter 24

§eleven. Initial information about the verb (25). § 12. Characteristics of conjugations. General idea of the dictionary (basic) forms of the verb (26). § 13. Basic (dictionary) forms of the verb (28). § 14. Praes-ensindicativiactivi. Imperativus praesentis activi (29). § 15. Negatives with verbs (31). § 16. Preliminary explanations for the translation (32). Exercises (38).

IV chapter 40

§ 17. Imperfectum indicativi activi (40). § 18. II declension. General remarks (41). § 19. Nouns of the II declension (42). §twenty. Phenomena common to I and II declinations (43). § 21. Adjectives I-II declensions (43). § 22. Possessive pronouns (45). § 23. Accusativus duplex (46). Exercises (46).

V chapter 47

§ 24. Futurum I indicativi activi (48). § 25. Demonstrative pronouns (49). § 26. Pronominal adjectives (51). § 27. Ablativus loci (52). Exercise(53).

Test 54

VI chapter 56

§ 28. III declension. General information(57). § 29. Nouns of the III declension (59). § 30. Correlation of forms of indirect cases with the form of the nominative case (60). § 31. Gender of nouns III declension (62). § 32. Ablativus temporis (62). Exercises (63).

VII chapter 64

§ 33. Adjectives of the III declension (64). § 34. Participium praesentis activi (66). § 35. Nouns of the III declension of the vowel type (67). Exercises (68).

Articles to read 69

II part

VIII Chapter 74

§ 36. Passive voice. Form and meaning of verbs (74). § 37. The concept of active and passive constructions (76). § 38. Personal and reflexive pronouns (78). § 39. Features of the use of personal, reflexive and possessive pronouns (79). § 40. Some meanings of genetivus (80). Exercises (81).

Chapter 82

§41. The tense system of the Latin verb (82). §42. The main types of formation of perfect and supine stems (83). § 43. Perfectum indicativi acti (84). § 44. Supinum and its derivational role (86). § 45. Par-ticipium perfecti passivi (87). § 46. Perfectum indicativi passivi (88). Exercise (89).

X Chapter 90

§ 47. Plusquamperfectum indicativi activi and passivi (91). § 48. Futurum II indicativi activi and passivi (92). § 49. Relative pronoun (93). § 50. The concept of complex sentences (94). § 51. Participium futuri activi (95). Exercise (96).

Test 97

XI Chapter 99

§ 52. The verb esse with prefixes (99). § 53. Compound verb posse (101). § 54. Accusativus cum infinitivo (102). § 55. Pronouns in turnover ace. With. inf. (103). § 56. Forms of the infinitive (104). § 57. Definition in the text and methods of translation of turnover ace. With. inf. (105). Exercises (107).

XII Chapter 108

§ 58. IV declension (109). § 59. Verba deponentia and semidepo-nentia (110). § 60. Nominativus cum infinitivo (112). § 61. Ablativus modi (113). Exercises (114).

XIII Chapter 115

§ 62. V declension (115). § 63. Dativus duplex (116). § 64. Demonstrative pronoun hie, haec, hoc (117). Exercises (117).

XIV Chapter 118

§ 65. Degrees of comparison of adjectives (119). Section 66. comparative(119). § 67. Superlatives (120). § 68. Formation of adverbs from adjectives. Degrees of comparison of adverbs (121). § 69. Suppletive degrees of comparison (122). Exercise (124)

Articles to read 125

III part

XV Chapter 129

§ 70. Participle turnovers (129). § 71. Ablativus absolutus (130). §72. Definition in the text and ways of translating turnover abl. abs. (132). § 73. Ablativus absolutus without participle (133). Exercises (134).

XVI Chapter 135

§ 74. Numerals (136). § 75. The use of numerals (137). § 76. Definitive pronoun idem (138). Exercise (138).

XVII Chapter 139

§ 77. Forms of the conjunctiva (139). § 78. Meanings of the conjunctiva (142). § 79. Shades of the meaning of the subjunctive in independent sentences (143). § 80. Additional and target clauses (144). § 81. Relative clauses of the corollary (146). Exercises (147).

XVIII Chapter 148

§ 82. Forms of the conjunctiva of the perfect group (149). § 83. The use of the subjunctive of the perfect group in independent sentences (150). § 84. Consecutio temporum (150). §85. Relative clauses are temporary, causal and concessive (151). Exercises (153).

XIX Chapter 154

§ 86. Indirect question (154). Exercise (155).

Test 155

XX Chapter 159

§ 87. Conditional sentences (159). Exercise (160).

XXI Chapter 161

§ 88. Gerund and gerund (161). § 89. Use of the gerund (162). § 90. Use of the gerund (164). § 91. Signs of difference between gerund and gerund and comparison of their meanings with the infinitive (164). Exercises (165).

IV part

Selected passages from the works of Latin authors

C. Julius Caesar. Commentarii de bello Gallico 168

M. Tullius Cicero. Oratio in Catilinam prima 172

Cornelius Nepos. Marcus Porcius Cato 184

C. Plinius Caecilis Secundus Minor. Epistulae 189

Velleius Paterculus. Historiae Romanae libri duo 194

Eutropius. Breviarium historiae Romanae ab U. c 203

Antonius Possevinus. De rebus Muscoviticie 211

Alexander Gvagninus. Muscoviae descriptio 214

P. Vergilius Maro. Aeneis 224

Q. Horatis Flaccus. Carmen. Satira 230

Phaedrus. Fabulae 234

Pater Noster 237

Ave, Maria 237

Gaudeamus 238

Aphorisms, winged words, abbreviations 240

grammar guide

Phonetics 250

Morphology 250

I. Parts of speech (250). P. Nouns. A. Case endings (251). B. Patterns of Declensions (252). V. Nominativus in the third declension (252). D. Features of the declension of individual nouns (253). III. Adjectives and their degrees of comparison (254). IV. Numerals (254). V. Pronouns (257). VI. Verb. A. The formation of verb forms from three stems (259). B. Depositional and semi-depositional verbs (262). B. Insufficient verbs (262). D. Archaic verbs (out of conjugations) (262). VII. Adverbs (266). VIII. Prepositions (267). Syntax simple sentence 267

IX. Word order in a sentence (267). X. Use of cases (268). XI. Accusativus cum infinitivo (271). XII. Nominativus cum infinitivo (272). XIII. Ablativus absolutus (272). XIV. Gerundium. Gerundivum (272). XV. Meaning of the conjunctiva (272).

Syntax complex sentence 273

XVI. Unions. A. Composing (most common) (273). B. Subordinating (most common) (274). XVII. Cop-secutio temporum (274). XVIII. Subject subordinate clauses(275). XIX. Definitive clauses (275). XX. Definitive sentences with adverbial meaning (276). XXI. Additional subordinate clauses (276). XXII. Relative clauses of purpose (276). XXIII. Relative clauses of the corollary (277). XXIV. Temporal subordinate clauses (277). XXV. Causal clauses (278). XXVI. Concessive subordinate clauses (278). XXVII. Conditional clauses (279). XXVIII. Indirect question (279). XXIX. Indirect speech (279). XXX. Attractio modi (280). XXXI. Relative clauses with conjunctions ut, quum, quod (280).

Elements of word formation 282

Applications 287

About Roman names 287

About the Roman calendar 288

On Latin Versification 292

About notes 293

About etymology and vocabulary 294

Key to control work 295

Latin-Russian dictionary 298

Latin language(or just Latin) for beginners and "from scratch" at school " European Education» - training is conducted via Skype.

Two languages have their roots in the history of European civilization - these are ancient Greek and Latin. They are also often referred to as classics.

ancient Greek language was the most important factor in the development of European civilization in its various spheres. It was the Greeks who laid the foundation of philosophy, the basis for natural and humanities, gave direction to the literature, and were also the first to demonstrate complex socio-political connections and relationships. It was Greek that became the first European language to have its own written language. Ancient civilization begins in Greece, but then the Roman Empire picks up the baton. AT Western Europe Rome brings further development, but it is no longer Greek that is the language of civilization, but Latin.

Latin belongs to the Indo-European family (along with Greek, English, German and others). Germanic languages), and later Romance languages arise on its basis: Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Romanian and others.

Latin was the language of live communication in the period from the 6th century BC. to VI n. e. One of the Italic peoples, Latini, was the first to use the Latin language. The Latins inhabited the central part of Italy - Latium (Latium). Starting from the VIII BC. e. Rome becomes their cultural and political center.

Throughout its thousand-year existence, the Latin language, like any other living language, has changed and replenished with new words and rules.

AT modern world Latin is considered dead (i.e. it is no longer used for live communication).

Today, Latin is needed by students of philological faculties, medical workers, lawyers, politicians, philosophers and representatives of some other professions. Besides, Latin terminology taken as a basis by other languages, remaining in its original form or subject to certain changes. It should be noted that in mathematics, physics and other sciences, conventions are still used, which often serve as an abbreviation of Latin words. In biology, medicine, pharmacology, and today they use a single international Latin nomenclature. Along with Italian, Latin is state language Vatican.

Since Roman science was built on the foundation of Greek, modern scientific terminology contains a significant Greco-Latin component.

Latin for beginners is a fairly broad concept, because its study has various goals. The teachers of our school will help you to clearly define the structure of the work and build a course that will be most focused on your goals and wishes. Even if the goal is the same for many, the paths to achieve it may be different. Since we are all different, we have different perceptions and understanding of the structure of the language, different memorization schemes, etc. The teacher tries to take into account individual characteristics each student in preparation for classes, which greatly facilitates the process of mastering a particular topic and the language as a whole. For example, if you are a medical student, then topics such as Latin and the basics of medical terminology, Latin for physicians, Latin for the study of pharmaceutical terminology, a brief anatomical dictionary, Latin terminology in the course of human anatomy, etc.

Each profession has its own programs and topics for study, which can be changed and supplemented in accordance with the wishes of the student.

It is better to study Latin for beginners for an hour and a half, and on days when you do not have classes, consolidate the material with shorter approaches. On weekends, you can devote a little more time to learning Latin. It should be remembered that working with a teacher is only part of the journey. To achieve the result, you need to put a lot of effort and independent work.

Latin phonetics is quite simple as it is based on the letters we are all familiar with (the Latin alphabet is the basis for almost all European languages). For beginners, it is more difficult to master the rules of reading in Latin. If you want to learn how to understand the language, and not just learn a couple of Latin proverbs and phrases, you need to master the grammar. Understanding the meaning of Latin texts is simply impossible without knowledge of grammar. The fact is that conjugation and other transformations of parts of speech occur according to certain rules, therefore, at the initial stages, textbooks often contain explanations and footnotes to texts to facilitate understanding and perception of the meaning of what is read.

It should also be remembered that the Latin course for beginners is not aimed at mastering spoken Latin (because Latin has not been used in English for a very long time). colloquial speech). A beginner's Latin course will help you master the grammar and vocabulary needed in your field.

You can learn Latin on your own if you approach this issue correctly. All you need is a set of the right textbooks, doing the exercises, and practicing Latin writing. Most likely, your relatives and friends will not be able to speak to you in Latin, but practice spoken language will help you improve your knowledge of Latin in general. If you try, you can speak Latin as well as the Pope, and in no time at all.

- Choosing the right dictionary is important for what you will be reading. If you are interested in Classical Latin, use Elementary Latin Dictionary or Oxford Latin Dictionary if you can buy it. If you are interested in late Latin, medieval, renaissance and neo-Latin, you are better off using the Lewis and Short's Latin Dictionary, although it is expensive. Otherwise, you will have to use Cassell, which is not very useful and not small in size. Unfortunately, choosing the right and inexpensive dictionary will not be easy.If you understand French, then the dictionary Grand Gaffiot would be a good choice.

- While you are still learning from a textbook, you will have to memorize a lot: declensions, conjugations, vocabulary. There is no shortcut. In this case, your morale is very important.

- Latin is a language with a poor vocabulary, in other words, one word can have several meanings. This also means that there are many idioms in Latin that you will also have to memorize. You will get to the point where you understand every word, but the meaning of the sentence as a whole will not be clear to you. This is because you think about the meaning of each word individually. For example, the expression hominem e medio tollere means "to kill a person", but if you do not know this phrase, then it literally translates to "remove a person from the center."

- Avoid poetry while you're still learning prose. Would you recommend reading Shakespeare to someone who teaches English language still unable to read the newspaper. The same applies to the Latin language.

- Learn words. Carry a list of words or flashcards with you to look up in the bus, restroom, or anywhere else.

- Write in Latin. Even if you want to learn how to read, don't skip the English-to-Latin translation exercise.

- Take your time. One session every few days is enough. If you are in a hurry, you will not have time to remember the information you need. On the other hand, don't hesitate. Try to exercise at least once a week.

- If your answers don't match those of the tutorial, chances are you're missing something. Get back to work and reread.