Letter letter. See what "Letter letter" is in other dictionaries

The alphabet includes:

- letters in their basic styles, arranged in a certain sequence;

- in some alphabets, diacritics or diacritical letters that indicate signs of sound or change the reading of a letter;

- names of letters and signs (Church Slav. "az", "beeches", "er"), usually containing the designated sounds or their signs in writing and pronunciation.

The number of letters of the alphabet roughly corresponds to the number of phonemes of the language (20–80), but alphabets, as a rule, only approximately reflect the phonetic system of the language, since the language changes over time, and the composition of written works expands and enriches due to multi-dialect and foreign texts, while the structure of the alphabet remains unchanged.

A developed system of letter writing, in addition to the alphabet, includes:

- graphics - a set of methods for displaying sounds in writing;

- spelling - a set of rules for writing words;

- punctuation - a set of rules for the division of written speech and the design of a written text through punctuation marks.

Types of the alphabet

Depending on the method of naming sounds, alphabets are divided into

- consonant,

- vocal and

- neosyllabic.

The letters of the consonant alphabets (Phenic, Hebrew, Arabic) denote consonant sounds or syllables with an indefinite outcome, vowel sounds are transmitted in writing through the so-called. reading mothers (matres lectionis) - letters denoting semi-vowels or aspirated sounds - or diacritics.

The letters of the vocal alphabets denote consonants and vowels (Greek a, b, g; Russian a, b, c, d), sometimes individual syllables (Russian e, u, z), thereby obtaining a clearly distinguishable sound value in writing .

The letters of the neosyllabic alphabets (Ind. Devanagari, Ethiopian) denote syllables of the same composition with an outcome in a vowel, initial vowels, vowel length, vowels; neosyllabic ind. alphabets are distinguished by a special matrix construction, in which the arrangement of sounds reflects the ratio of the distinguishing features of phonemes. The letters of a number of alphabets have a numerical value.

The emergence of alphabetic writing

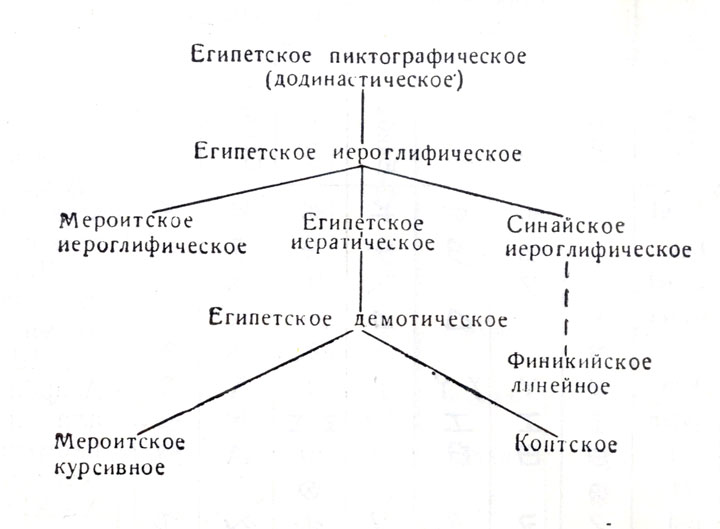

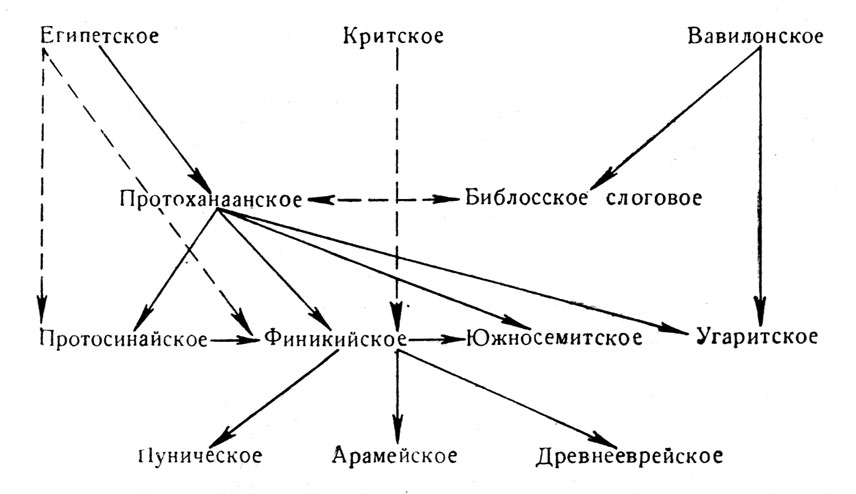

Alphabetical writing arose at the intersection of ancient written cultures: Egypt. hieroglyphics (early III millennium BC), Sumero-Akkadian. cuneiform (early III millennium BC), Cretan-Mycenaean (Aegean) hieroglyphics (early II millennium BC - not deciphered) and syllabic writing (1st half II millennium BC AD), which has been in use since about the 15th century. BC. for ancient Greek language (the so-called linear B), Hittite cuneiform (XVIII-XIII centuries BC) and hieroglyphics (XVI century BC) in the era of migrations and migrations of peoples - the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt (-1200 BC), the destruction of Troy and the Hittite kingdom (c. 1200 BC), the invasion of Canaan and Egypt by the “peoples of the sea”, the settlement of the tribes of Israel in Palestine.

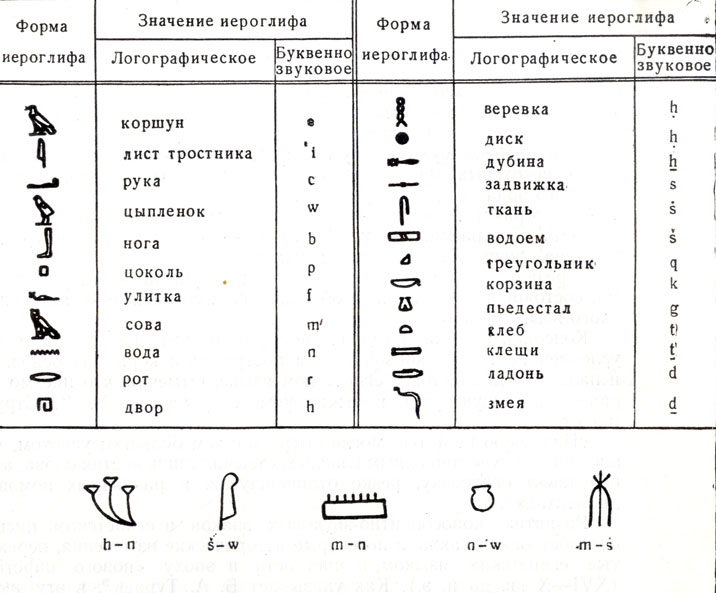

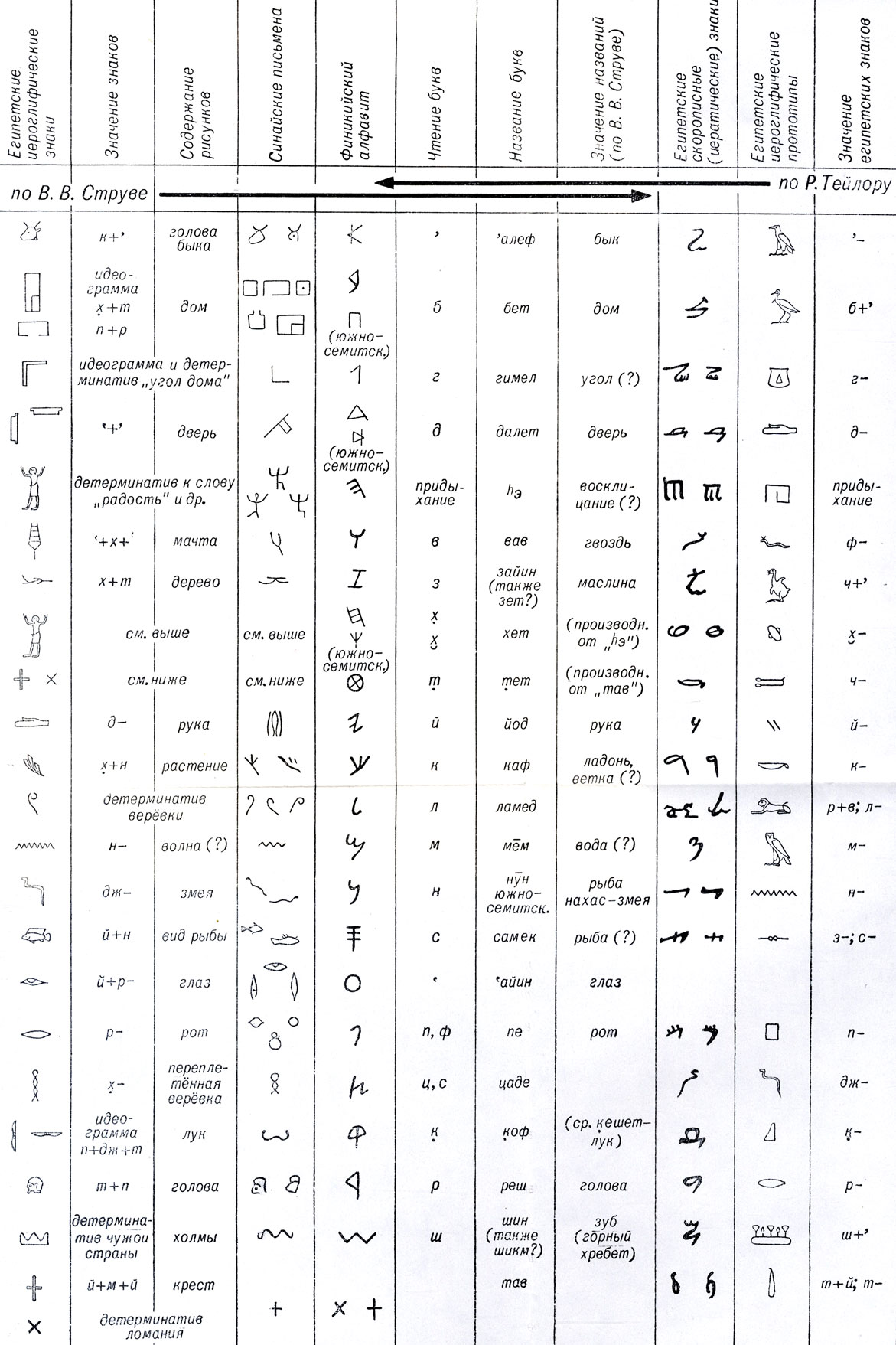

Ideographic writing contains determinative signs (designation of concepts) and the so-called. phonetic complements with syllabic or sound meaning; in Egyptian writing there are 23 signs with a sound value, which can be considered as the initial prototype of the alphabet. The creators of the first alphabets used the phonetic components of the ideographic writing (Egyptian and Akkadian), but rejected the ideographic and logographic signs associated with the religious and ideological representations of Egypt, Mesopotamia or Crete and with specific languages. Thus, alphabetic writing became a universal tool for fixing any language and began the rapid spread of writing among the peoples of Asia, Europe and Africa.

Among the West Semitic peoples, the alphabetic writing (Canaanite-Aramic group of Semitic languages) developed in the space from the North. Lebanon to the Sinai Peninsula in the 2nd half. II millennium BC The oldest cuneiform alphabet of Ugarit (the Mediterranean coast of Syria) dates back to the 13th century. BC. ; it contains 30 (later 22) characters denoting a Semite. consonants, the order of which is reproduced in subsequent alphabets, but the outline of the Ugaritic cuneiform letters does not correspond to the signs of other Semites. alphabets. Monuments of the syllabic writing of Byblos (XV century BC), Sinai-Palestine. letters of the middle - 2nd half. II millennium BC presumably associated with the tribes of the Philistines, who settled in the XIII-XI centuries. BC. a number of areas of Canaan. The oldest monuments of the South Semites date back to approximately the same time. letters from Arabia and Sinai. Canaanite, or phoenix, alphabet (22 letters), the first monuments of which date back to the 12th century. BC. , is considered the ancestor of Greek and Aramaic writing.

Eastern alphabets

Aram. a language that was used as an international language as far back as the Assyrians. period from the 6th century BC. became official language Achaemenid Persia and spread from Egypt to the North-West. India. Directly from the old-timers. alphabet formed Persian-Aram. (VI century BC) and Nabataean letter (II century BC), ind. A. - Indo-Bactrian Kharoshthi (mid-III century BC) and Brahmi (III century BC). These alphabets became the ancestors of the script families.

Heb. square writing (merubba) from the 4th century. BC. became the main alphabet of the Holy. Scriptures, but part of the books of the Old Testament (Gen. 31.47; Jeremiah 10; Ezra 4.8-18; 7.12-26, etc.) in biblical-aram. dialect was written in the Old Canaanite script in the 8th-7th centuries. BC. The Old Canaanite letter, represented by the “Dead Sea monuments” (II century BC - century A.D.) in the Paleoev. variant, gradually developed into the so-called. rabbinic (-4th century A.D.) letter of the Talmud and into the Middle Ages. heb. cursive, and then in modern. Hebrew letter.

The Indian Brahmi alphabet is based on Aram. letters, but, obviously, under the influence of ancient Greek. letters with its consistent vowel designation. The earliest Brahmi monuments date from the 3rd century BC. BC. (the reign of Ashoka, the spread of Buddhism), the Brahmi script is the oldest Indian script for Indo-European. language (Prakrit dialects). Brahmi and the script derived from it fell in the 1st century BC. BC. in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the Buddhist canon (tripitaka) was written down, which marked the beginning of the formation of the written literature of India. The Vedic texts were written down in the A.D.C. According to R. Kh., Brahmanism developed in India and the main body of Hindu written literature (Vedas, Upanishads, epic poems) took shape. In c. the Gupta alphabet, more perfect and adapted for classical Sanskrit, spreads along the R. Kh. On the gupta and the nagari that developed from it in the 7th-8th centuries. written classical Indian literature. The subsequent development of Nagari is the Devanagari (“divine urban”, XIII) century alphabet, on the basis of which the later scripts of India were formed.

The Nabataean script was used until c. according to R. Kh. and presented by Christ. epigraphic monuments. It underlies the Arab. A. (-VII) centuries, which took shape in the letter of the Koran and Islam. literature. With the spread of Islam, the Arab the letter supplanted the writing and literature of Syria, Mesopotamia, Iran, Bactria, Sev. India, Egypt, Libya, Nubia. Derived from Arabic. A. Writing systems are used by the languages Urdu, Farsi (modern Persian), Ottoman Tur. (to) and a number of others.

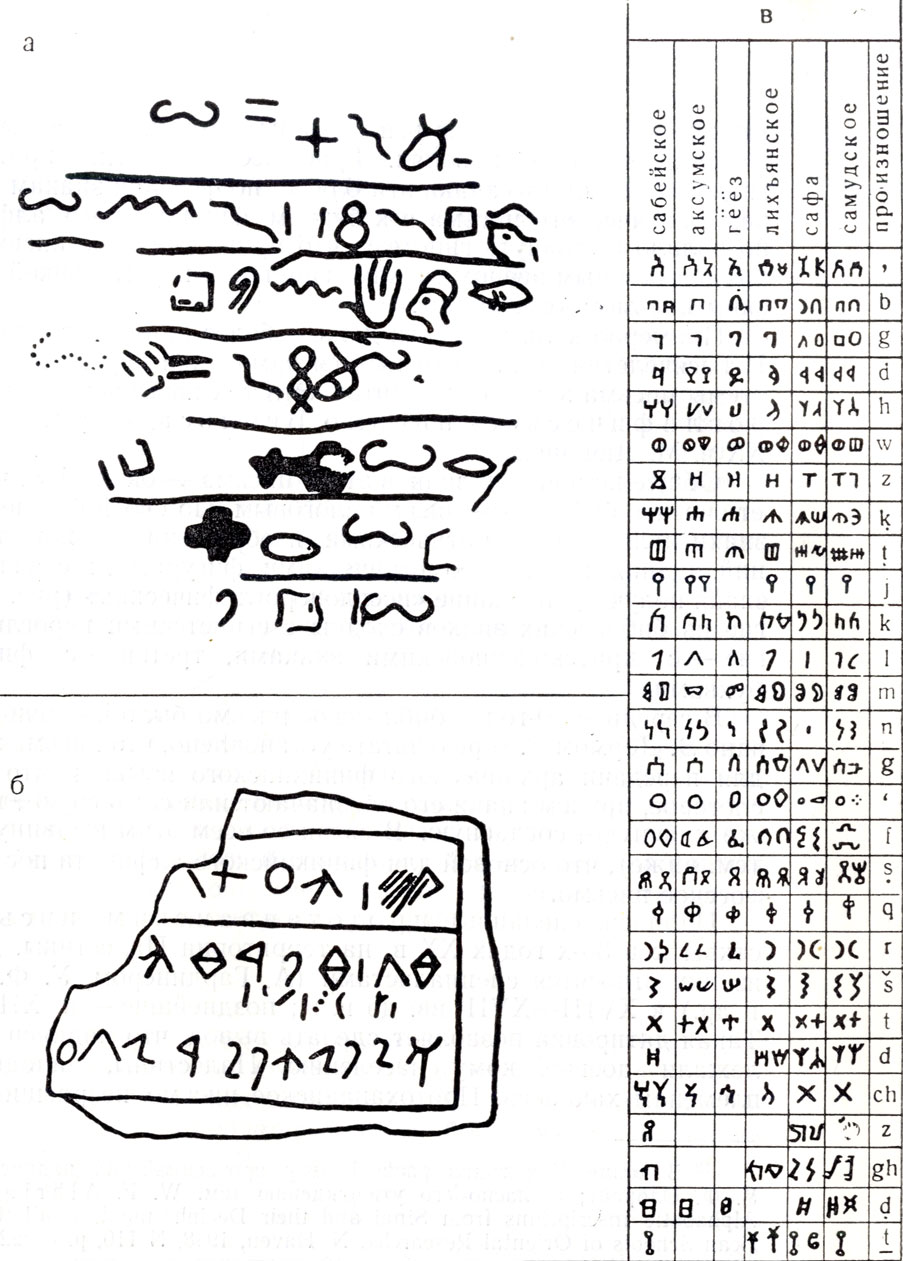

From South Arabian writing, which obviously arose very early, and is represented by the monuments of Yemen until the 7th century A.D., in - cc. according to R. Kh., the Ethiopian developed. syllabic alphabet. B - cc. in the Aksumite kingdom with the adoption of Christianity and the translation into the Geez language of the Holy. Ethiopian scriptures and liturgical literature. alphabet under the influence of Greek. letters has been significantly improved and, with some modifications, has been used to this day. time for the Amharic, Tigre and Tigrinya languages.

The writing of the Syrian kingdom of Palmyra (Tadmor) II century. BC. - III century. according to R. Kh. in aram. basis has played a significant role in the history of Eastern Christianity. At the beginning of the III century. according to R. Kh., a sir was created in Edessa. translation of the Holy Scriptures, for which the estrangelo alphabet was developed. Sir. Christ. Literature developed successfully until the 8th and even the 13th century. according to R. Kh. In the 1st floor. in. East-Sir was formed. "Nestorian" writing, which spread in Asia as far as Tibet, China and India.

Alphabet based on Greek script

Under the influence of the Phoenician letter in the –VIII centuries. BC. formed vocal Greek. and consonant aram. alphabet. In Greek. the letter developed the designation of vowel sounds, and the outline of the characters of the alphabet is represented by 2 options - east. (Hellas, M. Asia) and zap. (Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, the Mediterranean coast of modern France and Spain). K-V centuries. BC. east variant of the archaic Greek letters were transformed into classical Greek. a letter that developed in - centuries. according to R. Kh. in Byzantium. letter. In the century according to R. Kh. on the basis of the Greek. a cop was created. alphabet. All R. in. ep. Wulfil was created by a Goth. letter for the translation of the books of St. Scriptures and liturgical texts using Greek. letters and digraphs to designate specific germs. sounds. In con. in. ep. Mesrop Mashtots invented the arm. alphabet, which underlies the Armenian. liturgical and lit. language (grabar). In the beginning. in. cargo has been formed. alphabet.

Alphabet based on Latin script

From Western Greek alphabet developed Etruscan (7th century BC), lat. (VII century BC) letter and other Italian alphabets. Classical lat. writing was formed in the 3rd century. BC. Based on lat. alphabet, the writings of the peoples of the Zap were formed. Europe: Germanic runes (-III centuries AD), Irish (ogamic - c., Latin - end.) c., English (VII) c., French () c., Italian () c., Sardinian () c., Portuguese (XII) c., Polish (XVI) c. etc. The peculiarity of the formation of new scripts based on lat. alphabet lies in their transcriptional character: lat. the alphabet retains its composition and sound meanings of letters, and is used to record texts of predominantly secular content. At the same time, lit. bilingualism: St. Scripture, liturgical, theological, scientific literature persisted until the Reformation in lat. language, and secular literature, partly homiletics and business writing - in the vernacular.

Slavic alphabets

There are examples of the interpretation of the initial letters of her name: “Mater Alma Redemptoris, Incentivum Amoris”, “Maria Advocata Renatorum, Imperatrix Angelorum” (Mary, Intercessor for the Reborn, Ruler of Angels) and others (Barndenhewer O. Der Name Marias. 1895. S. 97ff). The 1420 manuscript contains a common interpretation: "Mediatrix, Auxiliatrix, Reparatrix, Imperatrix, Amatrix" (Mediator, Helper, Regenerator, Ruler, Loving).

The alphabet is one of the possible principles for organizing hymnographic material (see Acrostic). The full set of letters of the alphabet in the acrostic and their strict order symbolize the hymnographer's striving for perfection (in the OT: Ps 9; 10; 119; 142, etc. Lamentations 1-4). From Sir. and Byzantium. the writers of chants to the Old Testament examples were Saints Methodius of Olympus, Gregory the Theologian, Romanus the Melodist, John of Damascus; from lat. anthemists - Hilary of Pictavius ("Ante saecula"), Sedulius ("A solis ortus cardine"), Venantius Fortunatus (Hymnus de Leontio episcopo "Agnoscat").

The mystical interpretation of letters underlies the "magic" letter square-palindrome "Sator Arepo" ("ROTAS-formula"), which was written in Latin. or Greek. letters and when reading from left to right, from right to left, from top to bottom and from bottom to top, one and the same phrase was obtained: “Sator arepo tenet opera rotas”, “the sower Arepo holds the wheels with difficulty”.

The early use of this formula, dating back to 63, is evidenced by its discovery in Pompeii (2 graffiti) (for a list of places of early finds of the formula, see: Din-kler). Among the many attempts to explain the symbolism of these letters is the Christological interpretation of "Sator Arepo", in which the square is reduced to the cross "Pater Noster" with the center in the letter N and double AO (Grosser F. Ein neuer Vorschlag zur Deutung der Sator-Formel / / ARW 1926, Bd 24, pp. 165–169).

This letter square is widely used in Cyrillic transliteration in slav. (especially Russian) handwritten tradition -XIX centuries. and in popular prints of the 18th-19th centuries. titled "The Seals of the Wise King Solomon" or "The Seals of King Leo the Wise". Senior Russian. list, dated between and years. (The Explanatory Psalter with additional articles, rewritten in the Vologda Spaso-Prilutsky Monastery - YIAMZ. No. 15231). Later lists are very numerous, especially from the 17th century. Senior Yugoslav. (Serb.) the list was found in handwritten postscripts of the 17th century. to the edition of the New Testament with the Psalter (Ostrog, 1580). It is possible that an error in the 3rd word (“tepot” instead of “snare”) of the most ancient Rus. the list and a number of younger ones reflect the influence of the Glagolitic original (“n” and “p”, “e” and “o” have similar styles in the Glagolitic); if this assumption is true, the appearance of the "ROTAS-formula" in glories. writing should be attributed to a time no later than c. (later on, the monument was obviously transliterated more than once).

In the senior Russian the list (and a number of younger ones) the content of the “magic square” (“Seal of Solomon”) is interpreted as a symbolic designation of the nails driven into the hands and feet of the Savior during the crucifixion. In the lists of the XVII-XIX centuries. there is a recommendation to use the text "ROTAS-formulas" as a prayer from the bite of a rabid dog. In the lists of the XVIII-XIX centuries. and contemporary lubok engraving, the text is “deciphered” as an acrostic verse about the creation of the world and man, the global flood, the coming of the Savior into the world and His crucifixion, known in several. options. In manuscripts, the drawing of the "Seal of Solomon" is placed with the calendar-Easter texts in the following Psalms, Charters, calendars, "Circles of Peace", medical books and collections.

A well-known example of religion symbols of letters in lat. In the West, there are meditation crosses, on which letters are inscribed with no apparent meaning. Eg. in the Cross of Zechariah, which, according to legend, was opened to the fathers of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) during the plague (HWDA 9. 875), (ill.) the letters represent the beginnings of lat. prayers: Z - "Zelus domus tuae liberet me" (Zealous of your house, set me free); D - "Deus meus expellet pestem" (My God, may the plague be driven away). Here you can also name the “Cross of blessing” (Benediсtus), the first letters of which should have the meaning: “Crux Sacra Sit Mihi Lux / Non Draco Sit Mihi Dux” (Holy Cross be my light, let the dragon not be my driver) (HWDA 1 .1035). The magic formula "Ananisapta" was originally, apparently, a prayer-spell against the plague: "Antidotum Nazareni auferat necem intoxicationis, sanctificet alimenta poculaque trinitas, Amen" (May the antidote of the Nazarene take away death from poison, the Trinity sanctify food and drink. Amen) (HWDA 1.395).

In glory. medieval alphabetic cryptograms, usually dedicated to the praise of the Cross, are placed on the crosses (regardless of the technique of their execution) or near their images, both independent and crowning the composition of headpieces in handwritten and early printed books; hence their name - "cross (or cross) words." The most developed and complex cryptograms of this kind are placed in Serb. manuscripts of the 14th-16th centuries. (for example, in the Gospel Tetrs of 1372 - Vienna. National Library. Slav. 52. L. 69) and Venetian editions of the 16th century. printing houses of the Vukovichi (starting with the Prayer Book of 1536 with an engraving on L. 214v.), as well as on Old Believer cast crosses and folds of the 18th-19th centuries. (in some cases, Cyrillic transliteration of similar Greek cryptograms is possible for Serbian monuments of the XIV century). At least from the 2nd floor. in. in Russian manuscripts contain (interpretations) of the deciphering of the “words of the cross” (RGADA Typ. No. 387. L. 197 rev.-198, 90s).

Judaism

The Jewish doctrine of the symbolic meaning of letters was influenced by the idea of the pre-existence of the letters of Heb. alphabets that God used in the creation of the world and the creation of the Torah. Each letter of the alphabet, according to these ideas, has its own secret and symbolic meaning, by unraveling which one can penetrate the secrets of creation and the Torah. This meaning is revealed in the external form of letters, in the peculiarities of their pronunciation, combinations of letters and their numerical value. The earliest Jewish texts that reflect this view are midrashim from the Amoraic period. Examples of symbolic interpretation of some Heb. letters are given in the treatise "Genesis Rabbah", the earliest collection of midrashim to the book. Genesis (-3rd century A.D.). In the interpretation of Genesis 2. 4 (“when they were created”; in the Jewish editions of the Torah), the graphic outline of Heb. the letter (hey), open at the bottom and at the top left, is understood as an indication that evil people will be cast into hell, and for the few pious there is an opportunity to be saved (Genesis Rabba. 12. 10). The pronunciation of the letter "hey" is here considered as a sign that God created the world without difficulty, because "hey" is pronounced without tension - it's just a light exhalation (Genesis Rabbah. 12. 12). In the interpretation of Is. 26. 4 (“for the Lord God is an eternal stronghold”) the combination of the letters “Hey” and “Yod” is an indication of the existence of 2 worlds - this world and the world to come - while this world was created by the letter “Hey”, and the coming one - with the help of "iodine" (Jerus. Talmud, Hagaga 2. 77c, 45; Peshikta Rabbati 21; Midrash Tehillim 114 § 3; Babyl. Talmud Menachot 29).

In the introductory part of the treatise "Gereshit Rabbah" there is a question why God chose the letter "bet" (the 2nd letter of Heb. A., with which the first word of the Heb. Bible - "Gereshit" (In the beginning)) begins with it Toru. To this question, the Midrash on Genesis 1.1 gives several Answers: God preferred to create the world with the help of the letter "bet", because it symbolizes blessing, because Heb. begins with this letter. the word "blessing" (beraha), while from the first letter (aleph) - the word "curse" (arira) (Genesis Rabbah 1.10); in its graphic design, “bet” is open on the one hand, this was interpreted as an indication that one cannot ask what is above or below the earth, what happened before the creation of the world and will happen in the future (Genesis Rabbah 1.10); the numerical value of "bet" - 2, was also interpreted, which indicated the existence of 2 worlds - this world and the world to come (Genesis Rabbah 1.10).

A more systematic exposition of the Middle Ages. Jewish speculations about the graphic design of letters and their secret symbolic meaning are contained in the collections of midrash, known as the Alphabet of Rabbi Akiva. One of his editions (A) offers midrashim collected in a free associative connection to consonants and vowels that make up the name of individual Heb letters. alphabet. Eg. the name of the letter "alef" consists of the letters "alef", "lamed" and "pe"; in accordance with this, the next series of agadic utterances is introduced by biblical and other sayings, which in turn begin with the letters aleph, lamed, and ne. Dr. the edition of the "Alphabet of Rabbi Akiva" (B), on the contrary, contains midrashim starting with letters in reverse alphabetical order: each letter of the alphabet is first of all the last letter of Heb. alphabet "tav" - approaches God and asks that He use it first in the creation of the world and begin, thus, with her the text of the Torah. But God refuses all letters until the letter "bet" fits. All arguments in this dispute of letters are built on free association with the names of Heb. letters. In addition to the Alphabet of Rabbi Akiva, there are a number of other texts containing discussions about the allegorical and symbolic meaning of Heb. letters. Eg. "shin" means false, and "tav" means truth. The fact that the letters of the word "sheker" (lie) in Heb. alphabet are not far from each other, and the words "emet" (truth) are far enough away, it is interpreted that falsehood is common, and the truth, on the contrary, is rare (Babyl. Talmud, Shabbat 104a).

Significant distribution in Jude. exegesis received a gematric interpretation, examples of which are already given in the code of hermeneutic rules of Eliezer ben José the Galilean (ca. AD). An example of numerical gematria is seen in the story of Abraham's victory at the head of a detachment of 318 armed servants over 4 east. kings, while the name of Eliezer's servant is understood as an indication of the number of servants, since the numerical value of the letters that make up his name adds up to 318. An example of letter gematria is found by the interpreter in Jer. 51.1, where Babylonia is named (in synodal translation: "My adversaries"). If the letters that make up this word are replaced with paired ones, based on the rule: the first is replaced by the last, the second from the beginning - by the second from the end, the third - by the third from the end, etc., then the word (Chaldea) will be obtained. In midrashim, and later in Kabbalistic literature, the total numerical values of the letters of a certain word were interpreted as an indication of a secret relationship between various words in the Torah.

A complex form of letter symbolism is proposed in Jude. the book "Sefer Yetzirah" (Book of Creation, see Tantlevsky. S. 286-298) - a small text dating from to the VIII centuries. In the 2nd part of "Sefer Yetzirah" the letters of the alphabet are divided into 3 groups: 3 "mothers" (letters "Aleph", "Mem" and "Shin"), 7 doubled ones ("Bet", "Gimel", "Dalet", "kaf", "pe", "resh", "tav"), as well as 12 simple ones - the rest of the letters of the "Mother" alphabet are symbols of the 3 primary elements that underlie everything that exists - the silent letter "mem" symbolizes water in which dumb fish live; the hissing "shin" corresponds to the hissing fire and the airy "aleph" represents (spirit, air). According to the cosmogony of the Sefer Yetzirah, the first emanation of the Spirit of God was that which produced fire, from which in turn came water. These 3 basic substances exist potentially and only come into actual existence through the 3 "mothers". The cosmos, which arose from these 3 basic elements, consists of 3 parts: the world, the year (or time) and man. Each of these parts contains all 3 primary elements. Water formed the earth, from fire came the sky, the spirit produced the air between heaven and earth. 3 seasons - winter, summer and rainy period - correspond to water, fire and spirit. Man also consists of a head (corresponding to fire), a body (represented by the spirit), and other parts of the body (corresponding to water). 7 double letters produced 7 planets in continuous motion, now approaching the Earth, then moving away from it, which is justified by the soft or hard pronunciation of double letters, 7 days changing in time according to their relation to the planets, 7 holes in a person connecting him with the world, as a result of which its organs are subordinate to the planets. 12 simple letters created 12 signs of the zodiac, they belong to 12 months in time and 12 "leaders" in a person (arms, legs, kidneys, bile, entrails, stomach, liver, pancreas and spleen), which are subordinate to the signs of the zodiac. Along with this schematic theory, the book points out various methods of combining and replacing letters to form new words that name new phenomena. In Kabbalistic literature there are several. methods of interpretation, with the help of which the principles of interpretation first mentioned in the Sefer Yetzirah are developed, e.g. Kabbalistic authors began to rearrange the letters of the tetragram, greatly developing the idea that God revealed Himself in language. The Heb. mystics of the thirteenth century. in Yuzh. France.

Islam

Ibn al-Arabi (-), al-Buni (d.), al-Dairabi (d.), al-Ghazali (-) and others wrote about the mysticism of letters and magical manipulations with them (Dornseiff. Das Alphabet. S. 142; Brockelmann, Geschichte der arabis-chen Literatur, Weimar, 1898, Bd. 1. S. 426, 446, 497; Bd. 2. S. 323). 7 letters that were missing in the first sura of the Qur'an were interpreted as especially holy and correlated with 7 especially important names of God, days of the week and planets (Dornseiff. Das Alphabet. S. 142-143). The notion of the symbolic meaning of the letters of the alphabet developed primarily among the Hurufis (Birge; Schimmel). According to the teachings of the Hurufis, God reveals Himself in a human face, since the name of God Allah was written on the face of a person, especially the founder of the Fadl Allah sect from Asterabad: the letter “alif” forms a nose, the wings of the nose are two “lams”, the eyes form a letter "Ha". With the help of this symbolism, the Hurufis express a special relationship between God and man. In other, especially mystical, directions of Islam, the “science of letters” (Arab. Ilm alkhuruf) was used, according to which 28 letters are Arabic. alphabets were divided into 4 groups of 7 letters, each group was subordinated to one of the 4 elements (fire, air, water, earth). In connection with the numerical value of the letters of the word, especially the names of God, could be interpreted mantically. At the same time, the assessment of the Arab plays a significant role. language as the language of revelation of Allah and Arabic. letters as the letters on which the Qur'an was written.

Literature

- Rovinsky D. A. Russian folk pictures. St. Petersburg, 1881, vol. 3, pp. 187–188; T. 4. S. 581–586;

- Monier-Williams M. Religious Thought and Life in India. L., 1885. P. 196–202;

- Sauer J. Symbolik des Kirchgeb?udes. Frieburg, 1902, 1924;

- De Groot J. J. M. Universismus. B., 1918. S. 343;

- Gematria // Jewish Encyclopedia. M., 1991. T. 6. Art. 299-302;

- Sefer Yetzirah // Jewish Encyclopedia. M., 1991 . T. 14. Art. 178-186;

- Dornseiff F. Das Alphabet in Mystik und Magie. Lpz.; B., 1922, 1975 (Stoicheia; 7);

- idem. ABC // HWDA. bd. 1. S. 14-18;

- idem. Buchstabe // Ibid. S. 1697-1699;

- Hallo R. Zusätze zu Franz Dornseiff // ARW. 1925. Bd. 23. S. 166–174;

- Speransky M.N. Secret writing in the South Slavic and Russian monuments of writing. L., 1929. S. 134, 137 (ESF. Issue 4. 3);

- Winkler H. A. Siegel und Charaktere in der muhammedanischen Zauberei. b.; Lpz., 1930. 1980;

- Bertholet A. Die Macht der Schrift in Glauben und Aberglauben. Freiburg i. Br., 1949;

- Edsman C.-M. Alphabet- und Buchstabensymbolik // RGG. bd. 1. S. 246;

- Bareau A. Die Religionen Indiens. Stuttg., 1964. S. 186;

- Birge J. K. The Bektashi Order of Dervishes. L., 1965;

- Biedermann H. Lexikon der magischen Künste. Graz, 1968;

- Dinkler E. Sator Arepo // RGG3. bd. 5 Sp. 1373-1374;

- Schimmel A. Mystical Dimensions of Islam. Durham, 1975;

- Gruenwald I. Buchstabensymbolik II: Judentum // TRE. bd. 6. S. 306-309;

- Holtz G. Buchstabensymbolik IV: Christliche Buchstabensymbolik // TRE. bd. 6. S. 311-315;

- Mishina E. A. A group of early Russian engravings (2nd half of the 17th - early 18th centuries) / / PKNO, 1981. L., 1983. P. 234;

- Baar T. van der. On the Sator formula // Signs of Friendship: To Honor A. C. F. van Holk: Slavist. Linguist, Semiotician. Amst., 1984. P, 307–316;

- Ryan W. F. Solomon, Sator, Acrostics and Leo, the Wise in Russia // Oxford Slavonic Papers. Oxf., 1986. N. S. Vol. 19. P. 47–61;

- Pliguzov A.I., Turilov A.A. The most ancient South Slavic scribe 3rd quarter. 14th century // XRF. M., 1987. Issue. 3. S. 559.

Used materials

- Article from the second volume of the "Orthodox Encyclopedia"

The letter-sound writing in the general historical plan was formed later than the syllabic; in its pure form, consonant-sound writing appeared from the second half of the 2nd millennium, and vocalized-sound writing - from the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. e. Such a late appearance of alphabetic-sound writing is due to the fact that this letter implies an even more developed ability to decompose speech into its simplest elements - sounds. The emergence of alphabetic-sound writing was of great importance for the development of world culture. Thus, F. Engels associated the emergence of letter-sound systems with the transition from the era of "barbarism" to the era of "civilization". Describing the various stages of the era of "barbarism" that preceded "civilization", F. Engels wrote: "3. The highest stage. Begins with melting iron ore and passes into civilization through the invention of alphabetic writing and its use for recording verbal creativity"*.

*(F. Engels. The origin of the family, private property and the state. M., 1952, p. 25. Some authors erroneously attribute this statement of F. Engels not to the emergence of alphanumeric writing, but to the emergence of writing in general.)

True, when proposing a periodization of the history of society, developed on the basis of L. Morgan's scheme, F. Engels warned that it would remain in force only "as long as a significant expansion of the material does not force changes"*.

*(Ibid., p. 20).

At present, "Soviet science has abandoned the use of the periodization proposed by L. Morgan in the history of primitive society, since, reflecting only the stages of culture, it did not illuminate the process of development of production and production relations"*.

*(TSB, article "Savagery", ed. 2, vol. 14, M., 1952, p. 342 (see ibid article "Barbarity", vol. 6. 1951, p. 623).)

But even in the field of cultural history, it would now be wrong to link the transition of peoples to the era of "civilization" with the use of alphabetic-sound writing. In this case, one would have to consider the Indians and Japanese, who use syllabic writing, the Chinese, who still retain logographic writing, etc., to be "uncivilized". F. Engels relied in his work mainly on materials from the history of the peoples of Europe, America and Australia "and almost did not affect the history of the peoples of the middle and Far East. Meanwhile, for some of these peoples (for example, for the Japanese), syllabic writing turned out to be no less, and even more convenient for linguistic reasons, than alpha-sound writing. Mainly for linguistic reasons, the transition of the Chinese from logographic (more precisely, morphematic) to sound writing is also delayed.

However, for most of the peoples of the world, alphabetic-sound writing is undoubtedly the most convenient. In the languages of these peoples, the number of different sounds is much less than the number of different syllables, not to mention words. Therefore, the alphabetic-sound writing provides an accurate transmission of the languages of these peoples with the help of a minimum assortment of written characters (usually from two to four dozen) *; thus greatly facilitated the teaching of writing, its use and the spread of literacy. Thus, the emergence of alphabetic-sound writing played a major role in the development of culture, if not all, then most of the peoples of the world.

*(A larger number of letters - up to 50 - 6 - is required for the accurate transmission of only very few languages, for example, North Caucasian.)

The most ancient letter-sound systems of writing (Phoenician Hebrew, Aramaic, etc.) were consonant-sound systems, that is, their signs denoted only consonant sounds.

These systems arose and were fixed mainly among the peoples, in whose languages vowels were of less importance than "consonants. In these (Semitic, partly Hamitic) languages, the root stem of words was usually built from consonants; vowels, as if interlayering the root stem, changed and served to form the grammatical forms of various derived words.So, in the Hebrew language, the root stem K - T - L "kill" by layering it with different vowels formed the words: KeToL - the indefinite mood of the verb "kill", KoTeL - "murderer", KaTuL - " killed", etc.

The consonant structure of root words, enhancing the meaning of consonant sounds, as if emphasizing them, made it very easy to separate them from the composition of the word. On the other hand, since the root stems consisted of consonants, the use of only consonants in writing also made it almost impossible to understand words; as for the grammatical forms, they became clear from the context.

2

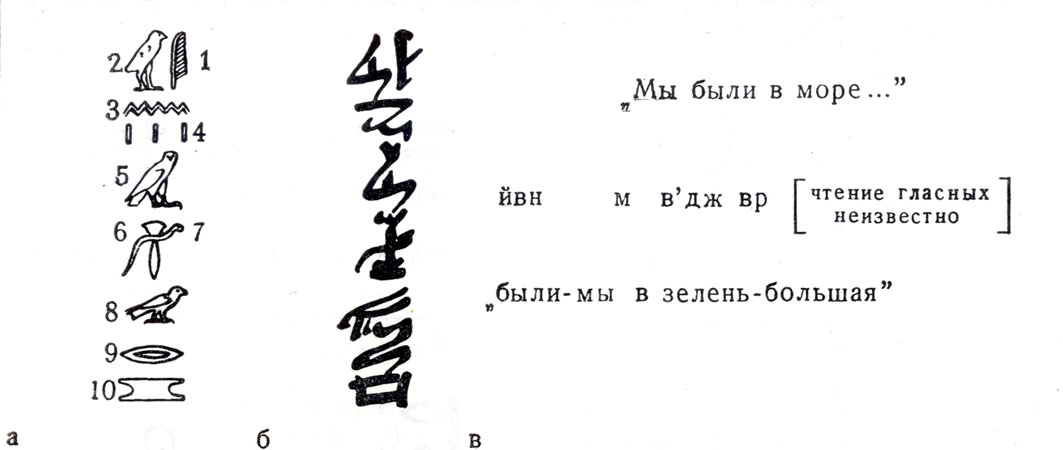

For the first time, consonant-sound signs appeared in Egyptian writing.

The ancient Egyptian language had (rad common features with the Semitic languages of Asia Minor and Asia Minor - with Assyro-Babylonian, Phoenician, Hebrew, etc. Thus, consonants were of the greatest importance in the Egyptian language (as well as in the Semitic ones). These sounds formed a clear skeleton of Egyptian words (for example, n - f - r "lute", h - p - r "beetle", etc.). As for the vowels, they mattered less than the consonants; in addition, they were used differently in various dialects of the Egyptian language *. Thanks to this feature (a clear consonant skeleton of words), individual words were relatively easy to distinguish from coherent speech; this greatly contributed to the development of logography from pictography. This also predetermined the consonant nature of the phonetic elements of Egyptian writing.

*(V. V. Struve. History of the ancient East. M., 1941, pp. 131, 231.)

Another important feature of the Egyptian language was that, while words that usually included two or three, and sometimes even four or five consonants, predominated, words that included only one consonant were also widely represented in it *. Logograms. denoting such (one-consonant) words, began to be used also to denote consonant sounds that were part of these words, regardless of which vowels these consonants were combined with; Thus, the logogram "mouth" (go) began to be used to designate the sound g, the logogram "valve" (za) - for the sound s, the logogram "reservoir" (sa) - for the sound s, the logogram "bread" (to) - for the sound t**.

*(So, according to the calculations of N. S. Petrovsky, about 30 one-consonant, about 80 two-consonant, about 60 three-consonant and only a few four-consonant signs were used in Egyptian hieroglyphic writing (N. S. Petrovsky. Egyptian language, M., 1958).)

*(The vocalization of Egyptian words given here is very approximate, since the vocalization of words is almost not reflected in the monuments of Egyptian writing and is restored mainly on the basis of later monuments of Coptic writing.)

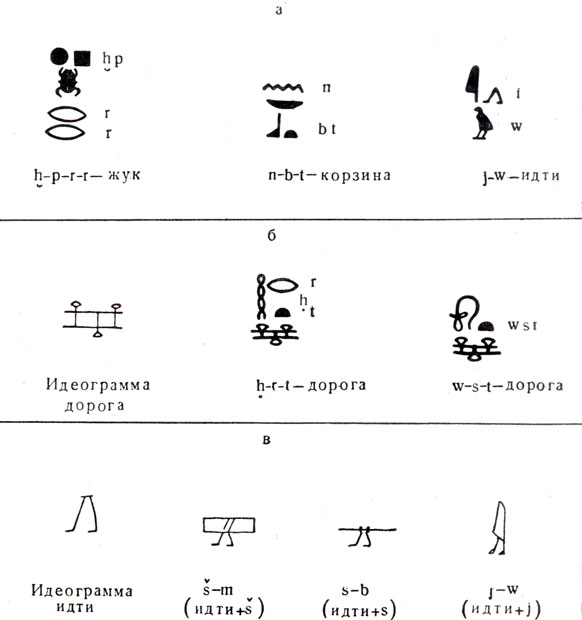

Along with monosonant logograms, some two-consonant logograms also turned into alpha-sound ones. At first, such logograms (Fig. 51) were used to convey similar-sounding parts of multi-syllable words (according to the so-called "rebus" writing method discussed in Chapter 4). Subsequently, the second consonant in some two-consonant logograms (for example, the feminine suffix t) with " rebus "writing of words ceased to be read. So, the logogram "snake" (d - t) began to be used to designate the sound d, the logogram "basket" (k - t) - for the sound k, the logogram "rope", "chain" (h - t) - for the sound h.

As a result, a whole alphabetic-sound system arose in Egypt, consisting of 24 signs denoting the consonant sounds of the Egyptian language (Fig. 51).

The consonant nature of the Egyptian writing, apparently, was due not only to the consonant construction of the root bases, but also to the presence of dialects in the Egyptian language. Noting that writing played a binding role in the Egyptian state, V. V. Struve writes:

"It could play such a role with all the greater success because the alphabet, being devoid of vowels, marked only "the Ostyak of the word, and did not convey the vowel, which differed sharply in various Nome dialects" *.

*(V. V. Struve. History of the Ancient East, p. 231.)

The development of consonant-sound signs in Egyptian writing was also facilitated by some historical changes experienced by the Egyptian language, in particular in the era of the "new kingdom" (XVI - X centuries BC). As B. A. Turaev * points out, in this era "the Egyptian language becomes analytical", and this was due to the simplification of the phonetic composition of words; so, the feminine suffix (t) disappears, some final sounds disappear (for example, g). This further increases the number of monosonant words and thereby contributes to the development of consonant-sound signs. In the same era in the Egyptian literary language a large number of words are poured from spoken language**; in connection with the entry of Egypt into the international arena, many words borrowed from foreign languages. There were no corresponding logograms for all these words in Egyptian writing. Therefore, these words turned out to be possible to convey mainly with the help of alphabetic-sound signs.

*(B. A. Turaev. Egyptian Literature. M., 1920, p. 22.)

**(Ibid., p. 21.)

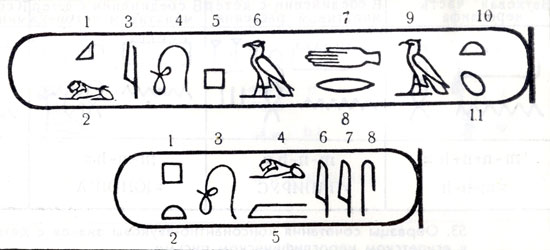

The sequence of characters in each name is indicated by ordinal numbers; the name of Ptolemy is read "Ptolmais", and the diphthong "ai" is conveyed by two hieroglyphs "i"; the last two characters in Cleopatra's account serve as a feminine indicator.

For these reasons, consonant-sound signs are used especially often in later monuments of Egyptian writing. The Egyptians, apparently, were aware of the convenience of these signs. Thus, V. V. Struve* notes that in “the only monument that has preserved the system of enumeration of Egyptian hieroglyphs, alphabetic characters are separated into a special group” (Fig. 51).

*(V. V. Struve. The Origin of the Alphabet, Pg., 1923, p. 17.)

Usually, 24 consonant-sound hieroglyphs were used in Egyptian writing. However, these hieroglyphs were not the only ones; along with them, especially in the late, Hellenistic era, other hieroglyphs were used to convey the same sounds, denoting other Egyptian words that began with the same consonants. Most often this happened when writing foreign words(Greek, Roman), in particular proper names; Thus, the hieroglyph "lion" (r - w) began to be used, along with the hieroglyph "mouth" (r -), to designate the sound r in the words Autocrator, Tiberius, etc., as well as to convey the sound l (Fig. 52) * .Changed in the Hellenistic era, the phonetic meaning of some of those shown in fig. 51 basic sound hieroglyphs. Thus, the hieroglyphs "kite" and "reed leaf", denoting "semi-vowel" sounds of the Egyptian language, began to be used (Fig. 52), apparently under Greek influence, to convey the vowel sounds a, e **.

*(M. Chaine. Notions de langue eguiptienne. Paris, 1938, p. 10. In particular, when using the hieroglyph "lion" to convey the sound r in the above words, the desire of the Egyptians to use the figurative-figurative meaning of hieroglyphs, even in the phonetic writing of words, affected.)

**(M. Chaine. Notions de langue egyptienne, p. 10 - 11.)

However, despite the ever more frequent use of phonetic, especially alpha-sound signs, despite the Egyptians' awareness of the convenience of these signs, Egyptian writing never became purely phonetic, and even more so alpha-sound.

This was due to two reasons. Firstly, due to the presence of homonyms in the language, as well as due to the omission of vowels in writing, many Egyptian words sounded the same when they were denoted by phonetic signs; for example, the word m - n - h meant "youth", "papyrus" and "wax". Therefore, these words required determinatives for their correct understanding; so, if the phonetically written word m - n - h meant "young man", after it the determinative "man" was placed; if this word meant "papyrus", the determinative "plant" was put; if it meant "wax", the determinative "loose bodies" was put (Fig. 53).

The number of such determinants was very large. In particular, it was necessary to use determinatives after the phonetic spelling of proper names, since Egyptian proper names "were all significant in themselves and under certain circumstances it was important to warn about their function of proper names" *. Sometimes a word written in phonetic signs was accompanied by more than one, and even several determinants**.

*(J. F. Champo11ion. Precis du systeme hieroglyphique des anciens egyptiennes. Paris, 1828, p. 416.)

**(M. Chaine. Notions de langue egyptienne, p. 16.)

54. Examples of the use of consonant-sound signs in Egyptian writing as "phonetic additions" to logograms, including (second and third rows) for phonetic discrimination of synonyms (according to J. Fevrier)

55. A sample of a hieroglyphic and hieratic Egyptian inscription with transcription, literal translation and analysis of the applied signs (borrowed with a change in terminology from the article "Letter" by I. Dyakonov, V. Istrin, R. Kinzhalov - TSB, ed. 2): a - hieroglyphic signs ; b - cursive writing (hieratics); c - the meaning and transcription of the inscription. 1, 2, 3 - single consonant signs j, w, n, originally used as ideographic logograms "reed leaf" (j), "chicken", "chick" (w), "water" (n - t) and used here for letter-sound spelling of the word "we were" (j - w - n); 4 - determinative of multiplicity, specifying the meaning of the expression jwn; - a single-consonant sign (originally the logogram "owl") denoting the preposition "in" (t); 6 - ideographic logogram "papyrus", "greenery" (w - d); 7 - single-consonant sign d (originally ideographic logogram d - t - "snake", used here as a phonetic addition to the word "papyrus", "greenery"; 8 - phonetic logogram w - r, denoting two homonymous Egyptian words "swallow" and " big"; 9 - one-consonant sign (originally ideographic logogram "mouth" - r), used here as a "phonetic addition" to the word w - r ("large"); 10 - determinative of water space (originally ideographic logogram "channel", giving writing w - d w - r ("big greens") new meaning "sea".

The second reason for the preservation of logographic signs was the traditionalism characteristic of Egyptian culture. In particular, for this reason, logograms continued to be used not only as determinants, but also for the independent designation of words. In these latter cases, the logogram was often supplemented with consonant-sound signs (Fig. 54). Such a "phonetic addition" was most often used if the logogram denoted several synonyms (for example, the "go" logogram, which denoted the synonyms s - m, s - b, j - w, or the logogram "road", denoting the synonyms w - s - t and h - r - t). "Phonetic additions" were also used when the logogram denoted general concept(for example, the concept of "tree" of any species), which required concretization, as well as for the transfer of Egyptian suffixes (for example, the feminine suffix t). The phonetic complement sometimes conveyed all the consonants of the word indicated by the logogram; in this case, the signs of the "phonetic addition" were usually located around the logogram (Fig. 54, a). Even more often, the "phonetic addition" conveyed only the initial or final sound of the word, in this case the phonetic addition was placed before the logogram or after it, and sometimes even merged with it into a ligature sign (Fig. 54, c). Thus, the Egyptian writing throughout its existence was a combined ideographic-phonetic system. It simultaneously used: 1) ideographic logograms (used independently and as determinatives); 2) phonetic logograms, 3) two-three-consonant signs that served to designate parts of words and are sometimes incorrectly called "syllabic signs"; 4) consonant-sound signs (Fig. 55). Despite such complexity of Egyptian writing, it played a great progressive role, served as the basis on which other, Semitic peoples later created a purely sound writing (Fig. 56).

The dotted line indicates the possible ways of development. The Coptic script was formed mainly on the basis of Greek, and the Egyptian script influenced the shape of some letters of the Coptic alphabet.

The direct offshoot of the Egyptian letter was, in addition, the alpha-sound, twenty-three-digit letter of the "Ethiopian" state of Meroe (I century BC - III - IV centuries AD); Egyptian writing also influenced the shape of some letters in Coptic writing (see p. 243).

The deciphering of Egyptian writing was hampered by the wrong view of Egyptian writing as purely logographic. The Egyptian letter was deciphered in the 20s of the 19th century. J. F. Champollion. For the first time, Champollion deciphered the names of King Ptolemy and Queen Cleopatra, written in alphanumeric characters on the Rosetta Stone and on Cleopatra's Needle; deciphering was helped by the fact that the text of the Rosetta Stone was written in Egyptian and Greek, in the Egyptian text proper names were enclosed in oval frames and many sounds, and therefore the hieroglyphs in the names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra coincided (Fig. 52).

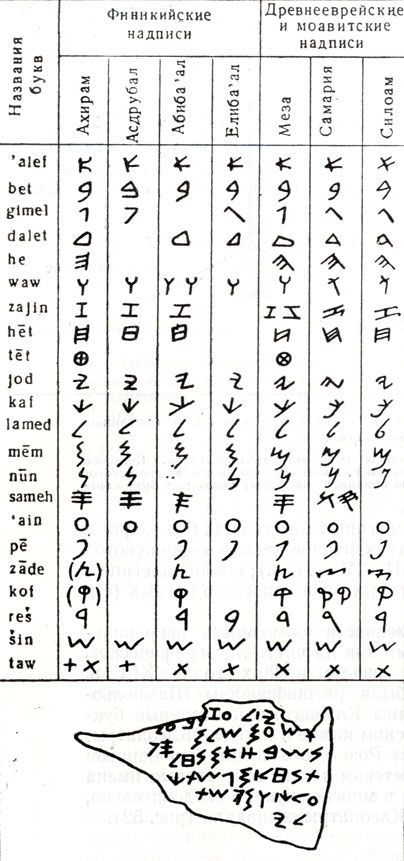

58. Phoenician alphabet. The meanings of letter names enclosed in brackets are debatable

3

The creation of the first purely sound writing system fell to the lot of the Phoenicians and other West Semitic peoples. The alphabetic-sound writing they created, due to its simplicity and accessibility, first became widespread among the neighbors of the Phoenicians, and then served as the initial basis for all subsequent alphabetic-sound systems.

The oldest monuments of the Phoenician pima that have come down to us (the inscriptions of Ahiram, Abdo, Shafatbaal, Asdrubaal, Azarbaal, Abibaal, Eliba-ala and others - Fig. 57) are currently attributed by most specialists to the 10th - 11th centuries. BC * Almost all the oldest inscriptions made in the Phoenician script are found mainly not in Phoenicia itself, but in the Phoenician colonies, in particular in Cyprus. Most of the inscriptions date from the 5th c. BC e. according to the II - III centuries. n. e. In the future, the Phoenician letter is supplanted by the Aramaic letter that arose on its basis.

*(16 G. R. Driver. Semitic Writing from Pictograph to Alphabet. London, 1948, p. 105; see also I. M. Vinnikov. Epitaph of Achiram of Byblos in a new light. "Bulletin of Ancient History", 1952, No. 2, pp. 150 - 152.)

57. The shape of the letters found in the oldest Phoenician and Hebrew-Moabite inscriptions, and a sample of the Phoenician inscription of the 10th - 11th centuries. BC e. The content of the inscription: "We gave Asdrubal ninety shekels of silver. If you repay, a loan for you and my loan for me ..." (according to J. Fevrier)

The Phoenician letter consisted of 22 characters (Fig. 58). Each of them denoted a separate sound of speech; no other signs - logographic, syllabic - were used in this letter. Thus, the Phoenician writing was (along with similar in type cuneiform Ugaritic, Proto-Sinaitic and Protoha "naanekim - see below) one of the very first; in the history of mankind, a purely sound (writing system.

![]()

The second feature of the Phoenician writing was that all its signs denoted consonants or semivowels (for example, waw - semivowel w, jod - semivowel j) sounds; as for vowels, they were skipped and not indicated when writing. Thus, the Phoenician writing was a typical consonant-sound system.

The third feature was that the Phoenician letters had a linear, simple, easy-to-remember and write form.

The fourth feature was the presence of an alphabet, that is, a certain order of enumeration and arrangement of letters. It should be noted that the alphabets of the Phoenician letter have not come down to us. Until the 30s - 40s of the XIX century. the order of letters in the Phoenician alphabet was established on the basis of the coincidence of the order of letters in the ancient Etruscan alphabets (the oldest - Marceline's alphabet - about 700 BC) with Hebrew acrostics Old Testament; both of them preserved the 22 letters of the Phoenician script. In the 1930s and 1940s, additional sources were discovered confirming the supposed order of the letters of the Phoenician alphabet. Such sources are: found in 1938 in Lagish (Palestine) a tablet with the Hebrew alphabet of the beginning of the 9th century. BC e. and a tablet with the Ugaritic cuneiform alphabet discovered in 1949 in Ugarit (see below).

The fifth feature of Phoenician writing was that each of its letters had a name; these names were built according to the acrophonic principle, that is, the sound value of the letter always corresponded to the first sound in the name of the letter (for example, b - bet, d - dalet, g - gimel, w - waw, etc.). Just like the order of the letters in the alphabet, the actual names of the Phoenician letters have not come down to us. The names of the Phoenician letters are judged on the basis of: the Hebrew names of these letters, which came down in Greek transcription and in the later Talmudic tradition; the names of the corresponding Greek letters that have come down from the 6th - 5th centuries. BC e.; names of letters in the Syriac alphabets of the 7th - 8th centuries. n. e. From the Phoenicians, the custom of assigning names to letters, also built according to the acrophonic principle, passed to the Arameans, Jews, Greeks, then to the Slavs, Arabs and other peoples.

The sixth feature was that the names of the Phoenician letters were associated not only with the sound meaning of the letters, but also with their graphic form; for example, the letter called waw, which means "nail" in Semitic, not only denoted the sound w, but also resembled a nail in shape. Some scientists (G. Bauer, V. Georgiev and others) deny the connection between the names of many Phoenician letters and their form. So, according to V. Georgiev, the names of the Phoenician letters fully correspond to their form only in four cases (mem, ain, res, taw) and partly in four more cases (alef, waw, jod, sin). As for the other letters, V. Georgiev either denies the connection of their names with the form or considers the Semitic etymology of the names disputable*.

*(V. Georgiev. Origin of the alphabet. "Problems of Linguistics", 1952.)

The direction of Phoenician writing was horizontal, from right to left. Words, as a rule, were not separated from each other.

A late form of Phoenician writing was Punic writing, which was used in the 4th - 2nd centuries. BC e. in Carthage and the Carthaginian colonies. After the fall of Carthage, the Punic script was partly supplanted by Latin, and partly passed into the New Punic script, which was used until the beginning of our era. The consonantal systems of the peoples of North Africa (Libyan, used from the 2nd century BC) and Spain (Iberian) come from the New Punic writing; the latest offshoot of the Libyan script is the modern script of the Tuareg of Central Sahara - "tifinak".

4

In addition to the Phoenician, several other West Semitic writing systems are known, as or even older than the Phoenician. Among them are three consonant-sound systems - Protokha-Naan, Proto-Sinaitic, Ugaritic cuneiform and one syllabic - the so-called "pseudo-hieroglyphic" writing of Byblos. In addition, almost simultaneously with the Phoenician, there were South Semitic writing systems of the Arabian Peninsula.

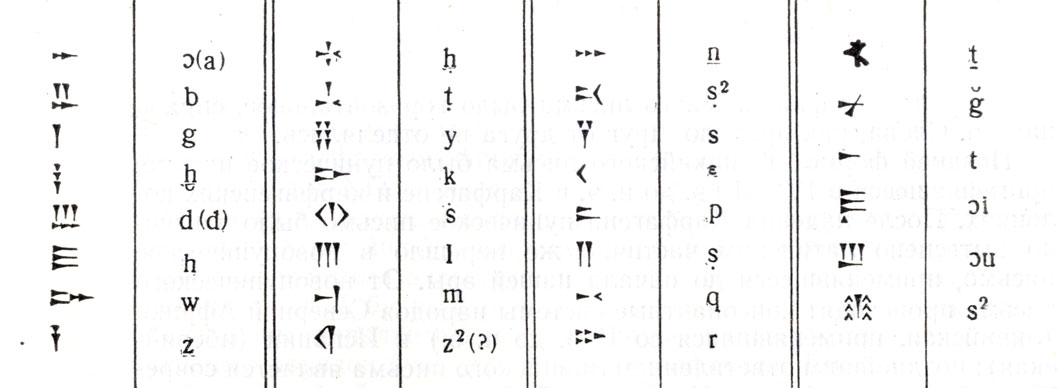

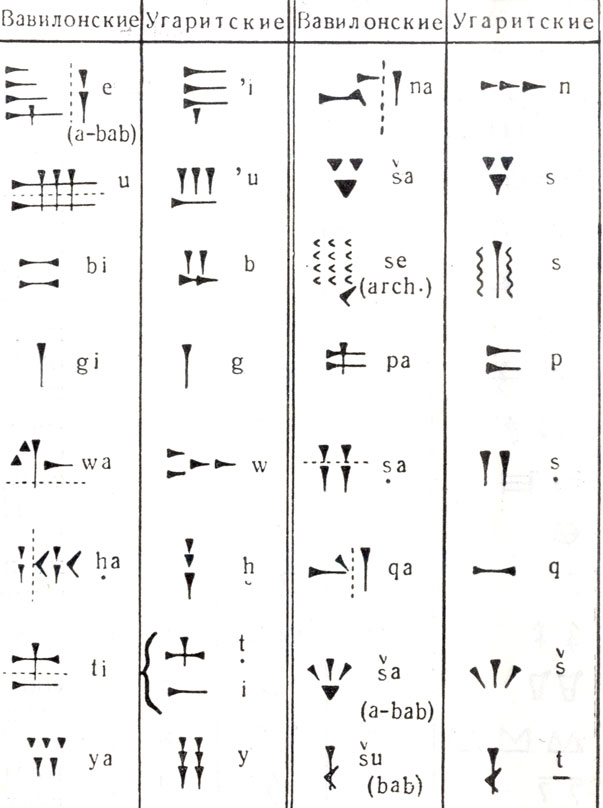

Ugaritic cuneiform consonant-sound writing used in the XV - XIII centuries. BC e. in the northernmost of the Phoenician cities, Ugarit; after the destruction of Ugarit by the Aegean tribes (about 1200 BC), the Ugaritic cuneiform was forgotten and had no effect on other writing systems.

Ugaritic writing used 30 consonant-sound signs (Fig. 59), IB including two signs that had almost the same sound value (s), and three signs for "alef, which are usually considered syllabic signs ("alef + vowels a, i , u). Of these signs, 22 signs coincide in sound value with the signs of the Phoenician script; two signs are additional "alephs"; one character is the second s, and five characters denote consonants not represented in the Phoenician script. The language of most Ugaritic inscriptions is West Semitic, close to Phoenician and being its older form. In 1949, a clay tablet with the Ugarit cuneiform alphabet was found in Ugarit. In this alphabet, 22 Ugaritic letters, identical in their sound value with the Phoenician ones, are in exactly the same order as in the Phoenician alphabet; of the remaining 8 letters, 3 are placed at the end of the alphabet, and 5 are placed inside it (Fig. 59).

Thus, the Ugaritic writing is very close to the Phoenician in terms of the consonant-sound type (the possible presence of two-three-syllable characters in it is due to the Assyrian influence) and in the sound meaning of most characters, and in the presence of an alphabet, and even in the order of the letters in the alphabet. The Ugaritic letter differed from the Phoenician in a completely different, cuneiform form of letters, which is also explained by the influence of the Assyrian-Babylonian cuneiform.

The inscriptions made in the Proto-Sinaitic script were discovered in 1904-1905. W. M. Petri Flinders "in the Sinai Peninsula, located on the way from Egypt to Phenicia. On this peninsula there were ancient Egyptian mines in which turquoise was mined. These mines were exploited three times: during the XII Egyptian dynasty, in the XVIII century BC. e. in the era of the Hyksos, i.e. in the 17th - 16th centuries, during the XVIII Egyptian dynasty, i.e. in the 15th century BC In this regard, some scholars (A. Gardiner) attribute the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions to the 18th century, others (K. Zethe and G. Bauer) - to the 17th - 16th centuries, others (W. M. Petrie-Flindersey W. F. Albright) - to the 15th century BC.

In total, several dozen inscriptions were found (Fig. 60, a); part at the entrance to the mine, part - in the temple of the turquoise goddess Gator. These inscriptions contain, according to some data, about 40 characters, according to others (considering some characters as graphic "variants") - about 32 characters. Such a small number of characters allows us to conclude that the inscriptions are made in alphabetic-sound writing.

In 1916, the English scientist A. Gardiner tried to decipher the Proto-Sinaitic script. He proceeded from the assumption that the inscriptions were made in the Semitic language and that each sign designates, according to the principle of acrophony, the initial consonant of the Semitic name of the object depicted by this sign. Based on this method, A. Gardiner managed to decipher two Semitic words that occur several times in the inscriptions dedicated to Gator: b - "- l - t" mistress", "goddess" and t - n - t - "gift" *. As a result it was hypothesized that these inscriptions were made by Semitic slaves working on Egyptian mines. Graphical analysis of the Proto-Sinaitic signs showed that these signs are close in shape to the signs of the Egyptian hieroglyphic script and to the letters of the Phoenician alphabet. This made it possible to put forward the hypothesis that the Proto-Sinaitic script is an intermediate link between Egyptian hieroglyphics and Phoenician writing (see below).

*(In the late 1940s, W. F. Albright continued to decipher the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions; according to his statement (see W. F. Albright. The Early Alphabetic Inscriptions from Sinai and their Decipherment. "Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research", N. Haven, 1948, N 110, p. 6 - 22), he succeeded in establishing the phonetic the meaning of 19 Proto-Sinaitic characters.)

Approximately to the same or even to an earlier time (beginning of the 2nd millennium BC) there are monuments of another ancient writing system of the Western Semites. This is the so-called "pseudo-hieroglyphic" letter of Byblos, discovered in the 20s of the XX century. M. Dunant.

The total number of characters of this letter is about 120, which allows us to consider the Byblos script as syllabic. In their form, Biblos signs are schematic representations of animals, plants, buildings, or geometric figures, in connection with which these signs are called "pseudo-hieroglyphic" (Fig. 60, b). Many of the Biblos signs are similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs, others to Cretan-Minoan signs, and still others to Phoenician letters.

In the mid-40s, the Byblos letter was partially deciphered by E. Dorm *. As a result, it was established that this letter served to (transmit the archaic Phoenician language and that the letter is syllabic, and its signs denote either a consonant + vowel or a vowel + consonant. In In connection with all this, a hypothesis was put forward (see below) that the Biblos script served as the basis for the Phoenician alphabet.

*(E. Dhorm. Dechifrement des inscriptions pseudohieroglyphiques de Byb-los, "Syria", Paris, -1, t. 25, fast. 1/2.)

Inscriptions made in the Proto-Canaanite script were discovered in the 30s of the 20th century. in the territory of Palestine. The oldest of them belong to specialists (A. Gardiner, W.F. Albright, etc.) to the 18th - 17th centuries. BC e.; later - to the XIII century. BC e. Such dating allows us to conclude that these inscriptions belonged to the pre-Jewish population of Palestine, the West Semitic tribes of the Canaanites. The Proto-Canaanite writing has not been deciphered, but, judging by the number of different characters found in it (30 - 40), it is alpha-sound. Graphical analysis of Proto-Canaanite characters showed that many of them are close to Proto-Sinaitic and Phoenician letters; in connection with this, a new hypothesis was put forward about the proto-Canaanite origin of Phoenician writing (see below).

These are the writing systems used by the Western Semites at the same time or even before the rise of the Phoenician alphabet.

Almost simultaneously with the Phoenician or a little later - at the end of the II or at the beginning of the I millennium BC. e. South Semitic writing systems emerged. These systems were created in the ancient states of the Arabian Peninsula - in the kingdoms of Main, Kataban, Hadhramaut - and existed before the Arab conquest of these states, that is, until the middle of the 1st millennium AD. e. (Fig. 60, c). The oldest South Semitic inscriptions date back to the 8th century. BC e. By the beginning of the XX century. these inscriptions were deciphered by J. Halevi, E. Littman and others.

The origin of the South Semitic script is not clear enough. Both in the number of letters and in their form, this letter differs significantly from Phoenician; therefore, many consider some proto-Semitic writing to be the basis of this letter (see below). Differing in many respects from Phoenician, the systems of South Semitic writing are very close to each other. These systems have about 30 consonants, most of which coincide (in different systems) both in sound value and in form. The graphics of the South Semitic writing were affected by the fact that the inscriptions were carved on stone, metal and other hard materials. The letters were written here vertically, without tilt, at an equal distance from each other; they are almost the same height and somewhat monotonous, geometric in shape.

5

Of great theoretical interest is the question of how and why a consistent letter-sound writing first appeared in history among the West Semitic peoples in the 2nd millennium BC. e. This question is often replaced by another, narrower one: which of the pre-existing writing systems served as the basis for West Semitic alphabetic-sound writing. As such a basis, three writing systems were indicated - Egyptian, Assyro-Babylonian and Cretan-Minoan. The theory of the largely independent emergence of the alphabetic-sound writing of the West Semitic peoples is also gaining more and more supporters.

Hypothesis of Assyro-Babylonian origin West Semitic, in particular Phoenician, writing was first put forward in 1877 by V. Dik and in late XIX in. developed by V. Peizer, partly by F. Delic, G. Zimmern and others.

At present, this hypothesis has almost lost its supporters. Its biggest drawback is that the Assyro-Babylonian and Phoenician writing systems are fundamentally different in type: the first is mainly a syllabic system with a fairly accurate designation of vowel sounds and using (along with syllabic signs) logograms; the second is a purely sonic and, at the same time, consonant system. Thus, this hypothesis cannot in any way explain the most important thing in Phoenician writing - its consistent consonant-sound principle. This shortcoming is further exacerbated by the fact that the history of writing does not know cases of the transition of syllabic systems into consonant-sound systems. Thus, G. R. Driver writes: “While the syllabary may develop from an alphabet of consonants, as the Ethiopian syllabary shows, the syllabary is a dead end from which there is no way out.”* This circumstance is also noted by the French historian of writing J. Fevrier**. The Assyro-Babylonian influence on the graphics of the Phoenician script is also unlikely, since the linear form of the Phoenician letters has nothing to do with the cuneiform form of the Assyro-Babylonian characters. The Assyrian-Babylonian hypothesis received some reinforcement after the discovery and decoding of the Ugaritic script of the 15th-13th centuries in the 30s. BC e. This letter, combining the wedge-shaped form of signs with their konoonamt-sound meaning, thus, it would seem, could be a link between the Assyro-Babylonian and linear Phoenician letters. However, attempts to derive Ugaritic characters from Assyro-Babylonian ones (K. Ebeling), and even more so attempts to derive linear Phoenician letters from Ugaritic cuneiform letters, did not give positive results (Fig. 61).

*()

**(J. Fevrier. Hisrtoire de 1 "ecriture. Paris, 1948.)

A find in 1949 illuminated the problem of the relationship between Ugaritic and Phoenician letters in a new way. clay tablet with the Ugaritic 30-letter alphabet. Sh. Virolo also noticed that the sign "ain" in the Ugaritic script was sometimes enclosed in a circle, similar to the circle of the Phoenician "ain"; in this regard, S. Virolo made an assumption about the possible influence of the Phoenician writing on the Ugaritic one. The discovery of the Ugaritic alphabet supported the assumption of S. Virolo. As already noted, in this alphabet, 22 Ugaritic letters, identical in sound value with the Phoenician ones, are in exactly the same order as in the Phoenician alphabet. Of the additional eight Ugaritic letters, three were placed at the end of the alphabet (just as the Greeks and Romans when adding new letters to the alphabets they borrowed); the rest of the additional letters are placed close to the letters similar to them in sound value.

Such a construction of the Ugaritic alphabet suggests that its creators were familiar with the Phoenician alphabet * or that both alphabets are offshoots of some more ancient and, apparently, 27-letter proto-Phoenician alphabet. And if the creators of the Ugaritic writing were familiar with the Phoenician (or proto-Phoenician) writing, then they probably borrowed from it the consonant-sound principle, which is convenient for the transmission of all Semitic languages. But accustomed to using clay for writing, which is not suitable for applying linear signs, the Ugaritans replaced the linear form of letters with a cuneiform **, well known to them from Assyro-Babylonian writing.

*(In this case, the emergence of the Phoenician alphabet is pushed back at least to the 14th century. BC e.)

**(For the same reason, the ancient Sumerians switched from linear to wedge-shaped signs.)

Cretan-Minoan hypothesis The origin of Phoenician writing was put forward at the end of the 19th century. A. Evans* and developed by H. Speyder, F. Chapoutier, and in recent years by the Bulgarian scientist V. Georgiev. Initially, a major flaw in this hypothesis was the lack of decipherment of the Minoan script; therefore, the Minoan signs had to be compared with the Phoenician ones only in form, regardless of their phonetic meaning. The situation changed in the 50s, when the Cretan-Minoan linear (syllabic) script was partially deciphered as a result of the work of the Czech scientist B. Grozny, the Bulgarian V. Georgiev, and especially the English scientists M. Ventris and J. Chadwick.

*(A. Evans. Scripta minoa, v. 1, Oxford, 1890, p. 77 et seq.)

The comparison of the Phoenician letters by V. Georgiev* with the Minoan syllabic signs close in meaning to them (meaning a syllable that began with the same or almost the same consonant sound that was transmitted by the corresponding Phoenician letter) showed the extreme closeness of the form of the Phoenician letters and the Minoan syllabic signs. Approximately 14 Phoenician letters almost coincide in their form with the Cretan-Minoan signs (see Fig. 62) and only about 8 letters are more distant in form. As for the names of the Phoenician letters, according to V. Georgiev, they were formed by replacing the Minoan names with Semitic words, although different in meaning, but corresponding to the shape of the borrowed letter and starting with the same sound that this letter denoted. So, the Minoan logogram ![]() (cattle, property, treasure), which later began to designate the syllable ko (go) in the Minoan Linear script, when borrowed by the Phoenicians, received, according to V. Georgiev (in accordance with the shape of the sign and its sound value), the Semitic name gimel - camel.

(cattle, property, treasure), which later began to designate the syllable ko (go) in the Minoan Linear script, when borrowed by the Phoenicians, received, according to V. Georgiev (in accordance with the shape of the sign and its sound value), the Semitic name gimel - camel.

*(V. Georgiev. Origin of the alphabet. "Problems of Linguistics", 1952, No. 6; see also V. Georgiev. Problems of the Minoan language. Sofia, 1953.)

62. Comparison of Phoenician letters with signs of linear Cretan writing (from the article "Letter" by I. Dyakonov, V. Istrin, R. Kinzhalov - TSB, ed. 2)

63. Comparison of Phoenician letters with Egyptian hieroglyphs, Sinai scripts and Egyptian hieratic signs (from the article "Letter" by I. Dyakonov, V. Istrin, R. Kinzhalova - TSB, ed. 2)

As additional arguments, supporters of the Cretan-Minoan hypothesis refer to the evidence of the Greek authors Diodorus Siculus and Photius. According to Diodorus: “While some say that the letters were invented by the Syrians, and the Phoenicians learned from them, who then passed them on to the Hellenes (and it was those who sailed with Cadmus to Europe that transmitted them), and that therefore the Hellenes call the letters Phoenician, others (we are talking about the Cretans) say that the Phoenicians were not the first inventors of letters, but only changed the shape of the letters and, since most people use this letter, they call it invented by the Phoenicians. According to Photius (IX century), the very name "Phoenician letter" is due (according to the Cretans) not by the fact that it was invented by the Phoenicians, but by the fact that date palm leaves were used as a material for this letter ("Phoenician letters. Lydians and Ionians erect their Phoenician Agenor. The Cretans object to them, saying that the name comes from writing on palm leaves") *.

*(V. Georgiev. Origin of the Alphabet, p. 80.)

Despite external persuasiveness, the Cretan-Minoan hypothesis has very weak points. Firstly, it has already been noted (ch. 5) that the deciphering of the Cretan-Mycenaean script has not yet been fully completed, “Especially controversial are attempts to reconstruct the alleged names of the Minoan letters. as well as Assyro-Babylonian) cannot in any way explain the most important thing in the Phoenician letter - its consistently sound character. Meanwhile, it is precisely this, and not the shape of the letters and not their names, that determined the special place occupied by the Phoenician alphabet in the history of writing. The improbability was also indicated above Finally, thirdly, if we reduce the Cretan-Mycenaean hypothesis to borrowing only the form of signs, then even in this case it does not agree well with chronology. Meanwhile, at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, in Phenicia itself, in Byblos, there already existed a syllabary, many of whose signs almost coincide with f Inician. Moreover, at about the same time, near Phenicia, on the Sinai Peninsula, and even earlier in Palestine, there were other Semitic and, judging by the number of characters, sound writing systems (proto-Sinaitic and proto-Naan), graphically also very close to the Phoenician. Why, then, did the Phoenicians look for in Crete what they had even earlier?

But how can the closeness of the form of many Phoenician and Minoan signs be explained? As J. Fevrier * rightly notes, in writing systems built according to a linear-schematic principle using geometric shapes, repetition of the shape of characters is always inevitable, even W. M. Pitry-Flinder ** showed that the shape of many Phoenician characters was found in Egypt even before the advent of hieroglyphic writing in the form of stamps of potters. However, the influence of the shape of the Minoan characters on the shape of the Phoenician letters is very likely.

*(J. Fevrier. Histoire de 1 "ecriture.)

**(W. M. F. Petri. The Formation of the Alphabet. London, 1912.)

Egyptian hypothesis The origin of the Phoenician letter has the largest number of supporters. This hypothesis was put forward at the end of the 19th century. F. Lenormand, and then in the 60s - 70s was developed and substantiated by the same Lenormand and E. de Rouge. At the same time, de Rouget, and after him I. Taylor, proceeded from hieratic Egyptian writing; F. Lenormand and after him I. Halevi - from the hieroglyphic.

The main advantage of the Egyptian hypothesis is that it is based not only on the similarity of the form of Egyptian and Phoenician signs. Egyptian writing, in addition, is the only one of the oldest writing systems in which alpha-sound (consonantal) signs were widely used, while the Minoan (linear) writing was syllabic, and the Assyro-Babylonian logographic-syllabic. The acrophonic principle was common in Egyptian and Phoenician writing, as well as (unlike Minoan) the direction of writing from right to left. Finally, much greater than the Minoan was the Egyptian influence on the culture of the Phoenicians and other northwestern Semitic peoples; in particular in the first half of the II millennium BC. e., i.e., during the period of the probable emergence of consonant-sound Semitic writing (see below), in Byblos many people could read and write in Egyptian.

The Egyptian hypothesis received strong support after the discovery in 1904-1905. on the Sinai Peninsula in the Egyptian mines of inscriptions, the signs of which turned out to be intermediate in form between Egyptian hieroglyphs and Phoenician letters.

In this regard, A. Gardiner and independently K. Sete put forward a hypothesis that the Sinai inscriptions were made by Semitic slaves who worked in the mines, that these inscriptions were written in one of the West Semitic languages in consonant-sound writing, and that they are a link between the Egyptian hieroglyphic and Phoenician linear script. In the USSR, the greatest proponent of this hypothesis is VV Struve.

According to V. V. Struve*, the Semites, borrowing Egyptian hieroglyphs, gave them, as a rule, a new, different sound meaning. This new sound value was connected by the principle of acrophony with the name and form of the borrowed hieroglyph. In accordance with its form, the hieroglyph received a new Semitic name; the first sound of this name acrophonically became the new sound value of the borrowed sign; for example, the Egyptian logogram h - t ("house"), when borrowed by the Semites, received, according to V. V. Struve, a new Semitic name bet ("house") and, accordingly, a new sound value b. Thus, according to the Egyptian-Sinai hypothesis of A. Gardiner, K. Sete, V. V. Struve, the Phoenician letters are close to their hieroglyphic prototypes in form, but, as a rule, do not coincide with them in phonetic meaning (Fig. 63). On the contrary, according to the Egyptian-hieratic hypothesis of I. Taylor, the Phoenician letters, as a rule, coincide with their supposed hieratic prototypes in phonetic meaning, but are not always close to them in form. Both are shortcomings of these hypotheses.

*(V. V. Struve. Origin of the alphabet.)

The Proto-Sinaitic hypothesis also has another weak point. Proto-Sinaitic writing was an accidental creation of Semitic slaves cut off from their homeland and arose at a distance from the major centers of Semitic culture. And this, in turn, makes it more plausible to look at the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions as one of the later offshoots, and not as the original basis of West Semitic writing. A revision of the Egyptian-Sinai hypothesis became necessary after the discovery of Proto-Canaanite inscriptions in Palestine in the 1930s. Judging by the number of characters used, these inscriptions are made in an alpha-sound consonant script. At the same time, the oldest of the Proto-Canaanite inscriptions date back to the 18th - 17th centuries. BC e. Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions belong to approximately the same or even later time (as indicated, W. M. Petrie Flinders and W. F. Albright date them to the 15th century, K. Zeta and G. Bauer - to the 17th - 16th centuries. , A. Gardiner - to the XVIII century BC). In connection with this, and also because many of the Proto-Canaanian letters are in their form, as it were, an intermediate link between the Proto-Sinaitic and Phoenician linear letters, two new hypotheses have been put forward. The first, put forward by A. Gardiner and T. H. Gaster*, is a modification of the former Egyptian-Sinai hypothesis. In accordance with Gardiner's dating of the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions (18th century BC), supporters of this hypothesis consider Proto-Canaanite writing a transitional form from Proto-Sinaitic to Phoenician. Thus, according to this theory, West Semitic writing developed along the complex path Egypt - Sinai - Canaan - Phoenicia.

*(T. N. Gaster. The archaic Inscriptions in Lachisch. London, 1940.)

The second hypothesis (W. F. Albright, F. M. Cross, D. N. Friedman* and others) is based on the dating of Sinai inscriptions of the 15th century. BC e. According to this hypothesis, the proto-Sinaitic letters developed from the most ancient proto-Canaanite (XVIII - XVII centuries BC), and the proto-Canaanite - from Egyptian hieroglyphic signs; along with this, the later Canaanite inscriptions of the 13th century. BC e. derived from Proto-Sinaitic. Thus, according to this hypothesis, West Semitic writing developed along an even more complex path Egypt - Canaan - Sinai - Canaan - Phoenicia.

*(F. M. Gross and D. N. Fredman. Early Hebrew Orthography. N. Haven, 1952.)

The weak point of both hypotheses is that they rely only on the similarity of the forms of signs without taking into account their phonetic meaning, since the Proto-Canaanite inscriptions have not been deciphered.

The complex problem of the origin of the Phoenician alphabet is complicated by the presence of another ancient variety of consonant-sound writing - South Semitic inscriptions found in Arabia. There are the following hypotheses regarding the origin of South Semitic writing. Some experts (M. Dunant) deduce South Semitic inscriptions, as well as other varieties of Semitic writing, from the "pseudo-hieroglyphic" syllabic writing of Byblos. Others (A. Evans, H. Yeesen, M. Lidzbarsky, partly W. F. Albright) believe that the South Semitic script, like the North Semitic script, comes from the Proto-Semitic consonant-sound script (the ancient Proto-Canaanite inscriptions are usually considered such a script). ). Still others (K. Zethe, H. Grimm, A. Gardiner) derive the South Semitic letter, like the North Semitic one, from Proto-Sinaitic.

All more In recent years, the theory of the largely independent emergence of Semitic consonantal-sound writing has gained supporters. Supporters of this theory are the authors of two major monographs on the history of writing - D. Deeringer and J. Fevrier *, as well as such specialists as G. Bauer, R. Dusseau, J. de Groot, J. Friedrich, R. Weil and others; parties to this theory is the author of this work.

*(D. D fringe d. The Alphabet. London, (2 ed.-1); J. Fevrier. Histoire de 1 "ecriture. Paris, 1948.)

Before proceeding to consider variants of this theory, it is necessary to recall once again that from the point of view of world history writing, the most important achievement of the Phoenicians and other Western Semites was by no means the creation of letters convenient in shape or their names constructed acrophonically. The most important achievement of these peoples was that for the first time in the history of mankind they created a letter based on a strictly sound principle. This is the reason why the Phoenician alphabet served as the initial basis for all later alphabetic-sound writing systems and played such a big role in the history of writing. This also explains the acuteness of disputes about the origin of the Phoenician alphabet. But a phenomenon that occurs for the first time in history cannot be explained external influences. The reasons for this phenomenon should be sought in the peculiar socio-historical, linguistic and other features of the people in which it arose. What was the reason for the emergence of a sequential-sound writing system among the Phoenicians and other neighboring Semitic peoples?