The most famous samurai. Interesting facts about the warriors of Japan - the great samurai. Also our blogs

Created in ancient times. At the turn of the first millennium, about three hundred years before our era, the developed Japanese culture, called Jomon by experts, reached its zenith. Fundamental modifications of this culture led to the revival of a new one, called Yaen by today's scientists. With the advent of Yaen, the national Japanese language began to take shape.

Modern male Japanese names and their meaning are determined by the division of society in the Yaen era into the ruling elite - clans, artisans - those who served these clans, and the lower class - slaves. A person's belonging to one or another social category was marked by a component of his name. For example, the component "uji" meant that a person has the privileges of a ruler, the component "be" - his belonging to the working class. Thus, whole genera were formed with names that included "uji" and "be". Of course, over time, the social status of the clan has changed significantly, along with the meaning of the name. Now the presence of these components in the name does not at all determine their position in society, but at least indicates their genealogical roots.

Until the 19th century, only exceptional noble persons close to the emperor had the right to surnames. The rest of the population of Japan was content with names and nicknames. Aristocrats - "kuge", and samurai - "bushi" were considered the chosen ones.

Samurai - a clan formed in the 7th century, when the first military usurper appeared in the history of Japan - the shogun - samurai Minamoto, but - Yerimoto. He laid the foundation for the formation of a privileged class called "samurai". The fall of the shogun Totukawa and the concentration of power in the hands of Emperor Mutsuhito created fertile ground for the prosperity of the military clan and the consolidation of its preferential benefits for many years to come.

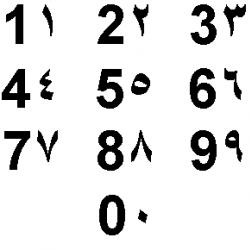

The names of the samurai were chosen according to the circumstances. It could be a place of service or receiving any awards. Due to their special position, they gained the right to independently name their vassals and often gave serial numbers to the names of their servants. For example, Ichiro is the first son, Goro is the fifth, Shiro is the third. The particles "iti", "go" and "si" in these names are serial numbers. Male Japanese names have retained this numbering trend to this day, but now it no longer bears such clear indications of belonging to the category of commoners. Samurai, having reached the period of youth, received the right to choose a new name for themselves. Sometimes they changed their names several times throughout their lives in order to signify in this way any significant dates in their biography. At the same time, the unfortunate servants were also renamed, regardless of their desire. What can you do - master-master!

It is curious that the serious illness of the samurai was also the reason for the name change. Only in this case, an exceptional method of naming was used - the patient was called “Buddha Amida”, hoping thereby to appeal to the mercy of the Buddha and defeat the disease. their fighting qualities. A good custom is to fight anonymously somehow uncomfortable! In reality, this rule was rarely followed. Probably because fights are a spontaneous event, and the opponents simply did not have time to get to know each other better.

Modern Japanese names are many varieties, where some of the elements inherited from their ancestors are certainly present. Male Japanese names and their meaning still depend on the serial number under which the boy appeared in the family. The suffixes "ichi" and "kazu" indicate that it was the firstborn, "ji" - the second male baby, "zo" - the third, etc. In particular, these are the names of Kyuuichi, Kenji, Ken-zo. But the Japanese are very careful with the “sin” particle - in translation it means “death”. A person named with such a particle is either doomed to a difficult fate, or makes the fate of other people difficult. So, if you happen to meet a Japanese person whose name contains "sin", you need to be careful. Unwittingly, he can bring misfortune.

Some male Japanese names and their meaning.

Akeno - Clear morning

Akio - Handsome

Akira - Smart, quick-witted

Akiyama - Autumn, mountain

Amida - Name of Buddha

Arata - Inexperienced

Benjiro - Enjoying the world

Botan - Peony

Dai - Great

Daichi - Great First Son

Daiki - Great Tree

Daisuke - Great Help

Fudo - God of fire and wisdom

Fujita - Field, meadow

Goro - Fifth son

Haru - Born in Spring

Hachiro - Eighth son

Hideaki - Brilliant, excellent

Hikaru - Light, shining

Hiroshi - Generous

Hotaka - The name of a mountain in Japan

Ichiro - First son

Isami - Courage

Jiro - Second son

Joben - Lover of cleanliness

Jomei - Bringer of light

Juro - Tenth son

Kado - Gate

Kanaya - Zealous

Kano - God of water

Katashi - Hardness

Katsu - Victory

Katsuo - Victorious Child

Katsuro - Victorious son

Kazuki - Joyful World

Kazuo - Sweet son

Keitaro - Blessed

Ken - Big Guy

Ken`ichi - Strong first son

Kenji - Strong second son

Kenshin - Heart of the sword

Kenta - Healthy and bold

Kichiro - Lucky Son

Kin - Golden

Kisho - Having a head on his shoulders

Kiyoshi - Quiet

Kohaku - Amber

Kuro - Ninth son

Kyo - Consent (or redhead)

Mamoru - Earth

Masa - Straight (human)

Masakazu - First son of Masa

Mashiro - Wide

Michio - A man with the strength of three thousand

Miki - Stalk

Mikio - Three woven trees

Minoru - Seed

Montaro - Big guy

Morio - Forest Boy

Nibori - Famous

Nikki - Two Trees

Nikko - Daylight

Osamu - Firmness of the Law

Rafu - Network

Raidon - God of Thunder

Renjiro - Honest

Renzo - Third son

Rinji - Peaceful forest

Roka - White crest of a wave

Rokuro - Sixth son

Ronin - Samurai without a master

Ryo - Superb

Ryoichi - Ryo's first son

RyoTa - Strong (obese)

Ryozo - Third son of Ryo

Ryuichi - First son of Ryu

Ryuu - Dragon

Saburo - Third son

Sachio - Luckily Born

Saniiro - Wonderful

Seiichi - First son of Sei

Sen - Tree Spirit

Shichiro - Seventh son

Shima - Islander

Shinichi - First son of Shin

Sho - Prosperity

Susumi - Moving forward (successful)

Tadao - Helpful

Takashi - Famous

Takehiko - Bamboo Prince

Takeo - Bamboo-like

Takeshi - Bamboo tree or brave

Takumi - Artisan

Tama - Gemstone

Taro - Firstborn

Teijo - Fair

Tomeo - Cautious person

Torio - Bird's Tail

Toru - Sea

Toshiro - Talented

Toya - House Door

Udo - Ginseng

Uyeda - From the rice field (child)

Yasuo - Peaceful

Yoshiro - Perfect Son

Yuki - Snow

Yukio - Cherished by God

Yuu - Noble blood

Yuudai - Great Hero

Perhaps, the whole world knows about Japanese samurai. They are sometimes compared with European knights, but this comparison is not entirely accurate. From Japanese, the word "samurai" is translated as "a person who serves." Medieval samurai were for the most part noble and fearless fighters, fighting against enemies with katanas and other weapons. But when did they appear, how did they live in different periods of Japanese history, and what rules did they follow? All this in our article.

The origin of the samurai as a class

Samurai appeared as a result of the Taika reforms that started in the Land of the Rising Sun in 646. These reforms can be called the largest socio-political transformations in the history of ancient Japan, which were carried out under the leadership of Prince Naka no Oe.

A great impetus to strengthen the samurai was given by Emperor Kammu at the beginning of the ninth century. This emperor turned to the existing regional clans for help in the war against the Ainu - another people who lived on the islands of the Japanese archipelago. Ainu, by the way, are now only a few tens of thousands left.

In the X-XII centuries, in the process of "showdowns" of the feudal lords, influential families were formed. They had their own fairly substantial military detachments, whose members were only nominally in the service of the emperor. In fact, every major feudal lord then needed well-trained professional warriors. They became samurai. During this period, the foundations of the unwritten samurai code "The Way of the Bow and Horse" were formed, which later transformed into a clear set of rules "The Way of the Warrior" ("Bushido").

Samurai in the era of the Minamoto shogunate and in the Edo era

The final formation of the samurai as a special privileged class occurred, according to most researchers, during the reign of the Minamoto house in the Land of the Rising Sun (this is the period from 1192 to 1333). The accession of the Minamoto was preceded by a civil war between the feudal clans. The very course of this war created the prerequisites for the emergence of the shogunate - a form of government with a shogun (that is, a military leader) at the head.

After the victory over the Taira clan, Minamoto no Yoritomo forced the emperor to give him the title of shogun (thus he became the first shogun), and he made the small settlement of Kamakura fishermen his own residence. Now the shogun was the most powerful person in the country: a samurai of the highest rank and chief minister at the same time. Of course, the official power in the Japanese state belonged to the emperor, and the court also had some influence. But the position of the court and the emperor still could not be called dominant - for example, the emperor was constantly forced to follow the instructions of the shogun, otherwise he would be forced to abdicate.

Yoritomo established a new governing body for Japan, called the "field headquarters". Like the shogun himself, almost all of his ministers were samurai. As a result, the principles of the samurai class spread to all areas of Japanese society.

Minomoto no Yorimoto - the first shogun and the highest ranking samurai of the late 12th century

It is believed that the "golden age" of the samurai was the period from the first shogun to the Onin civil war (1467-1477). On the one hand, it was a fairly peaceful period, on the other hand, the number of samurai was relatively small, which allowed them to have a good income.

Then, in the history of Japan, a period of many internecine wars began, in which the samurai took an active part.

In the middle of the 16th century, there was a feeling that the empire, shaken by conflicts, would forever fall apart into separate parts, but the daimyo (prince) from the island of Honshu, Oda Nobunaga, managed to start the process of unification of the state. This process was long, and only in 1598 was true autocracy established. Tokugawa Ieyasu became the ruler of Japan. He chose the city of Edo (now Tokyo) as his residence and became the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate, which ruled for more than 250 years (this era is also called the Edo era).

With the coming to power of the Tokugawa house, the samurai class increased significantly - almost every fifth Japanese became a samurai. Since internal feudal wars are a thing of the past, samurai military units at this time were used mainly to suppress peasant uprisings.

The most senior and important samurai were the so-called hatamoto - the direct vassals of the shogun. However, the bulk of the samurai performed the duties of daimyo vassals, and most often they did not have land, but received some kind of salary from their master. At the same time, they had quite a lot of privileges. For example, Tokugawa law allowed a samurai to kill a “commoner” who behaves indecently on the spot without any consequences.

There is a misconception that all samurai were fairly wealthy people. But it's not. Already under the Tokugawa shogunate, there were poor samurai who lived little better than ordinary peasants. And in order to feed their families, some of them still had to cultivate the land.

Education and code of the samurai

When educating future samurai, they tried to instill in them indifference to death, physical pain and fear, a cult of respect for elders and loyalty to their master. The mentor and the family, first of all, focused on the formation of the character of the young man who embarked on this path, developed in him courage, endurance and patience. The character was developed by reading stories about the exploits of heroes who glorified themselves as samurai of the past, watching the corresponding theatrical performances.

Sometimes the father ordered the future warrior in order for him to become bolder, to go alone to the cemetery or to another “bad” place. It was practiced by teenagers to visit public executions, they were also sent to inspect the bodies and heads of dead criminals. Moreover, the young man, the future samurai, was obliged to leave a special sign that would prove that he was not shirking, but really was here. Often, future samurai were forced to do hard work, spend sleepless nights, walk barefoot in winter, etc.

It is known for certain that the samurai were not only fearless, but also highly educated people. In the Bushido code, which was already mentioned above, it was said that a warrior must improve himself by any means. And so the samurai did not shy away from poetry, painting and ikebana, they did mathematics, calligraphy, and held tea ceremonies.

Zen Buddhism also had a huge influence on the samurai class. It came from China and spread throughout Japan in late XII century. Samurai Zen Buddhism as a religious movement seemed very attractive, as it contributed to the development of self-control, will and composure. In any situation, without unnecessary thoughts and doubts, the samurai had to go straight at the enemy, without looking back or to the side, in order to destroy him.

Another interesting fact: according to Bushido, the samurai was obliged to fulfill the orders of his master unquestioningly. And even if he ordered to commit suicide or go with a detachment of ten people against a thousandth army, this had to be done. By the way, the feudal lords sometimes gave the order to the samurai to go to certain death, to fight with a superior enemy, just to get rid of him. But one should not think that the samurai never passed from master to master. This often happened during skirmishes between petty feudal lords.

The worst thing for a samurai was to lose honor and cover himself with shame in battle. It was said of such people that they were not even worthy of death. Such a warrior wandered around the country and tried to earn money as an ordinary mercenary. Their services were used in Japan, but they were treated with disdain.

One of the most shocking things associated with samurai is the hara-kiri or seppuku ritual. A samurai had to commit suicide if he was unable to follow Bushido or was captured by enemies. And the seppuku ritual was seen as an honorable way to die. It's interesting that constituent parts This ritual was a solemn bathing, a meal with the most favorite food, writing the last poem - the tank. And next to the samurai performing the ritual, there was always a faithful comrade who, at a certain moment, had to cut off his head in order to end the torment.

Appearance, weapons and armor of the samurai

What medieval samurai looked like is reliably known from many sources. For many centuries they appearance almost did not change. Most often, samurai walked in wide trousers, resembling a skirt in cut, with a tuft of hair on their heads, called motodori. For this hairstyle, the forehead was shaved bald, and the remaining hair was braided into a knot and fixed at the crown.

As for weapons, throughout the long history of the samurai, they used different types of weapons. Initially, the main weapon was a thin short sword called chokuto. Then the samurai switched to curved swords, which eventually transformed into katanas known all over the world today. In the Bushido code, it was said that the soul of a samurai is enclosed in his katana. And it is not surprising that this sword was considered the most important attribute of a warrior. As a rule, katanas were used in tandem with daisho, a short copy of the main sword (daisho, by the way, only samurai had the right to wear - that is, it was an element of status).

In addition to swords, samurai also used bows, because with the development of military affairs, personal courage, the ability to fight the enemy in close combat, began to mean much less. And when gunpowder appeared in the 16th century, bows gave way to firearms and cannons. For example, flintlock guns called tanegashima were popular in the Edo period.

On the battlefield, samurai dressed in special armor - armor. This armor was luxuriously decorated, looked somewhat ridiculous, but at the same time, each part of it had its own specific function. The armor was both strong and flexible, allowing the wearer to move freely on the battlefield. Armor was made of metal plates tied together with leather and silk laces. The arms were protected by rectangular shoulder shields and armored sleeves. Sometimes such a sleeve was not worn on the right hand to make it easier to fight.

An integral element of the armor was Kabuto's helmet. Its bowl-shaped part was made of metal plates connected with rivets. An interesting feature of this helmet is the presence of a balaclava (exactly like Darth Vader from Star Wars). It protected the neck of the owner from possible blows of swords and arrows. Along with helmets, samurai sometimes wore gloomy Mengu masks to intimidate the enemy.

In general, this combat vestment was very effective, and the United States Army, as experts say, created the first bulletproof vests just on the basis of medieval Japanese armor.

The sunset of the samurai class

The beginning of the collapse of the samurai class is due to the fact that the daimyo no longer needed large personal detachments of warriors, as was the case during the period of feudal fragmentation. As a result, many samurai were left out of work, turned into ronin (samurai without a master) or ninja - secret assassins-mercenaries.

And by the middle of the eighteenth century, the process of extinction of the samurai class of samurai began to go even faster. The development of manufactories and the strengthening of the position of the bourgeoisie led to a gradual degeneration (primarily economic) of the samurai. More and more samurai fell into debt with moneylenders. Many of the warriors changed their qualifications and turned into ordinary merchants and farmers. In addition, the samurai became participants and organizers of various schools of martial arts, the tea ceremony, engraving, Zen philosophy, and belles-lettres - this was how the heightened craving of these people for traditional Japanese culture was expressed.

After the Meiji bourgeois revolution of 1867-1868, the samurai, like other feudal classes, were officially abolished, but for some time they retained their privileged position.

Those samurai who, even under the Tokugawa, actually owned the land, after the agrarian reforms of 1872–1873, legally secured their rights to it. In addition, the ranks of officials, army and navy officers, etc. were replenished with former samurai.

And in 1876, the famous "Decree on the prohibition of swords" was issued in Japan. It expressly forbade the carrying of traditional edged weapons, and this ultimately "finished off" the samurai. Over time, they have become just a part of history, and their traditions - an element of the unique Japanese flavor.

Documentary film "Times and Warriors. Samurai.

In the early morning of the twenty-fourth of September 1877, the era of the samurai ended. It ended romantically, somewhat tragically and beautifully in its own way. Most readers probably even imagine what it is about: to the sad music of Hans Zimmer, young idealists in funny medieval Japanese armor, along with Tom Cruise, were dying under a hail of bullets from Gatling machine guns. These Hollywood samurai tried to cling to their glorious past, which consisted of worshiping the lord, meditating before the sword, and keeping their sacred country clean from dirty white barbarians. The viewer squeezed out a tear and empathized with the noble and wise Ken Watanabe.

Now let's see how it really was. It was no less beautiful, sad, but still a little different than in The Last Samurai.

Briefly about what Japan had to go through three hundred years before that memorable date.

Civil War between a bunch of daimyo, remembered as "Shingoku Jidai", left us with a legacy not only of the word for the name of the Jedi order, but also in the long term the regime of the Tokugawa shogunate. For about two hundred and fifty years, the Tokugawa shoguns ruled Japan, having previously isolated it from outside world. Two and a half centuries of isolation gave Japan an amazing opportunity to preserve the medieval way of life, while in Europe Russia was building St. Petersburg and smashing the Swedish Empire, the Thirteen Colonies were at war with Britain for independence, the Bastille was being dismantled in Paris, and Napoleon was watching the dying guards at Waterloo. Japan remained in the warm and cozy sixteenth century, where it was extremely comfortable.

Japan was pulled out of cozy isolation by force in the middle of the nineteenth century. Americans, British, Russians, French - all of them became interested in Asia. Holy Empire in the blink of an eye she found herself in the middle of a large, aggressive and alien world. A world that was technically ahead of Japan by two hundred years.

The culprit in this situation was found quickly. The Tokugawa shogunate was blamed for all the sins, which failed to protect its country from white barbarians. An influential opposition front was formed in the country in the domains of Choshu and Satsuma, which expressed its tasks in a short slogan: “sonno joi”. Or "restore the Emperor, drive out the barbarians."

Yes, there was an emperor in Japan, just real power did not have, the shoguns ruled for him. This opposition to the shogunate initially did not find the strength to do more than guerrilla war and terrorist acts against unwanted servants of the shogun and Europeans. The break came a little later.

A young man named Itō Hirobumi, an idealist revolutionary who had already come to light with his active participation in the burning of the British embassy in Edo, was hired by the ruler of the Choshu domain for a covert operation. Together with four young people, they were secretly taken to China, where they were hired as sailors on a British ship. Their goal was to get into the enemy's lair - London - and collect information about their enemy.

Seen in the UK, Ito Hirobumi was enough to turn the whole idea of the world of a young Japanese upside down. He hurriedly returned to his homeland, where he decided to make every effort to modernize the backward country and bring it into the club of world powers as soon as possible.

About Ito Hirobumi should be told in a separate article. This is the man who actually created the Japanese Empire. He created a constitution, became the first prime minister of the country, under him Japan occupied Korea, defeated Russia in the war of 1905 ... But so far the country is still ruled by a weakening shogun, who is opposed by the sonno joi movement. By this time, however, the second part had already fallen off this slogan: it became clear that the war with the white invaders would be the end of Japan. The task was to restore imperial power.

The task was completed in 1868. Ito Hirobumi, Saigo Takamori, Yamagata Aritomo, Okubo Toshimichi and other former radical revolutionaries, together with an army of forces loyal to the emperor, captured the imperial palace, and then managed to finish off the forces loyal to the shogun. Two hundred and fifty years of the Tokugawa era is over.

Emperor Meiji formed a new government, which included the heroes of the revolution. Japan began to immediately catch up on what had been lost in two hundred and fifty years.

Of course, a new life is impossible without reforms. The Japanese with fanaticism refused everything that seemed to them outdated and not corresponding to the new time. One of these reforms affected the army. Samurai and feudal lords were a thing of the past, in their place a modernly equipped professional army had to come, like everywhere else in the world. And if there were no problems with modern equipment (America, Germany, France and Russia were happy to sell firearms and artillery to the Japanese), then difficulties arose with the reform of the entire system. In order not to delve into the subtleties: the military system of Japan differed very little from the medieval European system. There was a supreme ruler, there were feudal daimyo, there were personal squads of bushi samurai warriors. In the nineteenth century, this approach has already outlived its effectiveness for three hundred years. The daimyo became poorer and lost their lands, the samurai became poorer after them.

There was also one but. Throughout almost their entire history, the Japanese fought quite a lot and, mostly, with each other. After Japan was united under Tokugawa at the beginning of the 17th century, peace and tranquility reigned in the country. By the nineteenth century, Japan's military class had not been at war for generations. Samurai have become a relic of a bygone era, they were arrogant gentlemen spoiled by their privileges, engaged in poetry, conversations in night gardens and tea parties. Well, imagine the army of a country that has not fought for two and a half centuries. An original spectacle, isn't it?

But the samurai took the upcoming abolition of their privileges and the reform of the entire political life of the country painfully. They still saw themselves as the guardians of the true warrior spirit and traditions of Japan. Saigo Takamori, the hero of the revolution, was looking for a way to prove the need to preserve the ancient system. The new government, which included the above-mentioned revolutionaries along with Saigoµ, considered the possibility of war with Korea and its annexation. Decrepit China, devastated by two opium wars and corroded from all sides by Europeans, could no longer protect its old ally, and Saigo Takamori demanded to take advantage of the situation. Ito Hirobumi was categorically against it: Japan needs peace, and we will deal with expansion later. In the end, the emperor himself supported the peace party. Saigoµ spat, packed up his belongings and left the capital for his homeland, the domain of Satsuma. There he abandoned politics, dug in his garden, walked, hunted and wrote poetry.

“Since ancient times, unfortunate fate has been the usual price for earthly glory,

Where better to wander through the forest to your hut, carrying a hoe on your shoulder.

But soon other disgruntled samurai began to flock to Satsuma, mostly of an extremely young age. Saigo Takamori was still a hero and role model. The former military man decided to help young people find their place in life and opened several academies for them, where young men studied science, including military science. Infantry and artillery schools were opened, Saigoµ willingly bought weapons for his wards.

Of course, it all looked suspicious. It is not known for certain whether Saigoµ was preparing an open rebellion. Personally, I am inclined to doubt this, but the government thought otherwise. Soon, the students brought a "spy" to Saigoµ, who, after being tortured, revealed that he had been sent there to gather information and then kill Takamori Saigoµ. Confessions after being tortured gave the students a moral justification for retaliating. Soon they, having learned about the plans of the government to transport weapons from the warehouses of Saigo Takamori to Osaka, decided to prevent this and secretly stole guns and cannons from the arsenals. Unbeknownst to Saigo Takamori.

At that time he was in the forest hunting. Upon returning and hearing about what had happened, Saigoµ lost his temper. What happened was an open rebellion. There was nothing to do. Saigoµ could not leave his charges to their fate. With a heavy heart, he announced the mobilization of forces loyal to him, making it clear that he was not going to oppose the power of the emperor. His former comrades-in-arms, who discriminate against subjects who faithfully served him, are his true enemies.

The very first battle was a serious test for Saigoµ. They laid siege to Kumamoto Castle, hoping for an easy victory, but to Saigoµ's surprise, the castle garrison repelled one attack after another, although it consisted of conscripts, volunteers, merchants and peasants. Of course, the castle itself also played a significant role - although it was three hundred years old, it still remained a formidable and impregnable fortress, unattainable for the light artillery of Saigo Takamori.

The siege dragged on, the imperial army came to the aid of the defenders. Takamori's troops were defeated, after which he began to retreat back to Satsuma. This retreat was long and bloody. Supplies, equipment, weapons - all this was not enough. Some rebellious samurai armed themselves with swords and went into the forests to partisan. Saigo Takamori and about five hundred of his remaining followers were on their way to their own deaths.

The swan song of the samurai was the Battle of Shiroyama. Five hundred idealistic samurai, armed at random and with whatever, were surrounded by the imperial army, commanded by Saigo's old friend Yamagato Aritomo. Thirty thousand professional soldiers were thoroughly prepared to attack an enemy sixty times their number. Yamagato tried to persuade Saigoµ to settle the matter amicably, but the last samurai did not answer his friend's letter.

In the early morning of the twenty-fourth of September 1877, the era of the samurai ended. It ended romantically, somewhat tragically and beautifully in its own way. Yes, the samurai were armed with swords as they charged at guns and artillery in a suicidal charge. But the point here was not a fundamental rejection of new weapons - they simply had no ammunition left. Saigoµ could save his life and surrender - but is that the way out for a samurai? His death was instantly overgrown with legends, they say, the warrior pierced by a bullet knelt down, turned towards Kyoto and ripped open his stomach.

Saigo Takamori had no intention of getting in the way of progress and modernization. He was smart enough to understand the pointlessness of it. The last samurai became a victim of circumstances, and later a national hero, who was officially pardoned by the emperor. Japan has entered a completely new era.

In the history of the world there have always been such groups of people whose image has forever remained romanticized in people's hearts. Western pop culture draws on European and American heroic figures, bringing them to life in westerns, medieval films and fairy tales, in countries where kings and queens ruled. Cowboys and knights have always served as an ideal image for creating popular media products, thanks to the countless adventures and exciting situations in which they find themselves with enviable consistency.

Samurai were the equivalent of European knights, a noble military class in medieval Japan. For hundreds of years, samurai have played an important sacred role in Japanese society. The samurai swore allegiance to his master and undertook to serve him with his blade and wisdom, following a certain set of moral and philosophical rules called bushido. Following the path of bushido helped the samurai realize the concepts of chivalry, achieve mastery in martial arts, honor such concepts as devotion, honor, service, and prefer death to dishonor. Some samurai could become commanders by right of inheritance, without waiting for the will of the master.

After stories about the samurai spread beyond Japan, people from all over the planet took a keen interest in their history. It was actually very exciting: the samurai embodied the image of an ideal warrior who respected culture and laws, who was serious about his chosen life path. When a samurai failed his master or himself, according to local customs, he had to be subjected to the seppuku ritual - ritual suicide. In our list, you will find ten of the greatest samurai who lived in Japan at one time or another.

10. Hojo Ujitsuna (1487 - 1541)

Hojo Ujitsuna was the son of Hojo Souna, the founder of the Hojo clan, who controlled a large swath of the Kanto region, Japan's most populous island, during the Sengoku period (1467-1603). The Sengoku period was characterized by constant wars between families of high-ranking military personnel, and Hojo Ujitsuna was lucky to be born during this period of time, in 1487. Ujitsuna rekindled a long-standing feud with the Uesugi clan by taking over Edo Castle in 1524, one of the main centers of power in medieval Japan. He managed to extend his family's influence throughout the Kanto region, and by the time of his death in 1541, the Hojo clan was one of the most powerful and dominant families in Japan.

9. Hattori Hanzo (1542 - 1596)

This name may be familiar to fans of Quentin Tarantino's work, since it was on the basis of the real biography of Hattori Hanzo that Quentin created the image of a swordsman for the film "Kill Bill". O early period Not much is known about Hanzo's life, but historians tend to believe that he was born in 1542. From the age of 16, he fought for survival, participating in many battles. Hanzo was devoted to Tokugawa Ieyasu, saving the life of this man more than once, who later founded the shogunate that ruled Japan for over 250 years, from 1603 to 1868. Throughout Japan, he is known as a great and devoted samurai who has become a legend. His name can be found carved at the entrance to the imperial palace.

8. Uesugi Kenshin (1530 - 1578)

Uesugi Kenshin was a strong military leader and part-time leader of the Nagao clan. He was noted for his outstanding ability as a commander, resulting in many victories for his troops on the battlefield. His rivalry with the Takeda Shingen, another warlord, was one of the most famous in history during the Sengoku period. They feuded for 14 years, during which time they participated in several one-on-one fights. Kenshin died in 1578, the circumstances of his death remain unclear. Modern historians believe that it was something similar to stomach cancer.

7. Shimazu Yoshihisa (1533 - 1611)

This is another Japanese warlord who lived throughout the bloody Sengoku period. Born in 1533, he proved himself as a talented commander as a young man, a trait that later enabled him and his comrades to take over most of the Kyushu region. Thanks to his success on the battlefield, he earned the unconditional loyalty of his servants (sworn swords, as they were called) who fought desperately for him on the battlefield. Yoshihisa was the first to unify the entire Kyushu region, and was later defeated by Toyotomi Hideyoshi and his 200,000-strong army.

6. Mori Motonari (1497 - 1571)

Mori Motonari grew up in relative obscurity, but that didn't stop him from taking control of some of the largest clans in Japan and becoming one of the most feared and powerful warlords of the Sengoku period. His appearance on the general stage was sudden, just as unexpected was the series of victories that he won over strong and respected rivals. Ultimately, he captured 10 of the 11 Chugoku provinces. Many of his victories were won against much more numerous and more experienced opponents, which made his exploits even more impressive.

5. Miyamoto Musashi (1584 - 1645)

Miyamoto Musashi was a samurai whose words and opinions still bear an imprint on modern Japan. Musashi was a ronin, a masterless samurai who lived during the Sengoku period. Today he is known as the author of The Book of Five Rings, which describes the strategy and philosophy of the samurai in battle. He was the first to apply a new fighting style in the technique of wielding a kenjutsu sword, calling it niten ichi, when the battle is fought with two swords. According to legend, he traveled through ancient Japan, and during the journey he managed to win in many fights. His ideas, strategies, tactics and philosophy are the subject of study to this day.

4. Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536 - 1598)

Toyotomi Hideyoshi is considered one of Japan's Founding Fathers, one of three men whose actions helped unify Japan and end the long and bloody era of Sengoku. Hideyoshi replaced his former master, Oda Nobunaga, and began to implement social and cultural reforms that determined the future direction of Japan for a period of 250 years. He banned the possession of a sword by non-samurai, and also began a nationwide search for all swords and other weapons that should henceforth belong only to samurai. Although this concentrated all military power in the hands of the samurai, such a move was a huge breakthrough on the path to common peace since the reign of the Sengoku era.

3. Takeda Shingen (1521 - 1573)

Takeda Shingen was arguably the most dangerous commander of all time in the Sengoku era. He was born the heir of the Takeda family, but personally seized power when it turned out that his father was going to leave everything to his other son. Shingen allied with several other powerful samurai clans, which pushed him to go beyond his native province of Kai. Shingen became one of the few who was able to defeat the army of Oda Nabunaga, who at that time successfully captured other territories of Japan. He died in 1573 suffering from an illness, but by this point he was well on his way to consolidating power over all of Japan. Many historians believe that if he had not fallen ill, then Oda Nabunaga would never have come to power again.

2. Oda Nobunaga (1534 - 1582)

Oda Nobunaga was driving force unification of Japan. He was the first warlord who rallied around him a huge number of provinces and made his samurai the dominant military force throughout Japan. By 1559, he had already captured his native province of Owari and decided to continue what he had begun, expanding his borders. For 20 years, Nobunaga slowly rose to power, presenting himself as one of the country's most feared military leaders. Only a couple of people, among whom was Takeda Shingen, managed to win victories in the fight against his unique military tactics and strategy. Fortunately for Nobunaga, Shingen died and left the country to be torn to pieces. In 1582, at the height of his power, Nobunaga was the victim of a coup d'état launched by his own general, Akeshi Mitsuhide. Realizing that defeat was inevitable, Nobunaga retreated inside the Honno-ji temple in Kyoto and committed seppuku (ritual suicide of the samurai).

1. Tokugawa Ieyasu

Tokugawa Ieyasu may not have been the most efficient samurai, but by the end of the Sengoku period he was the man with the best cards. Ieyasu concluded an alliance between the Tokugawa and Oda Nobunaga clans, but with the death of the latter, the huge military forces found themselves without a commander in chief. Although Toyotomi Hideyoshi replaced Nobunaga, his absolute power over the country lasted for a very short time. From 1584 to 1598, Tokugawa Ieyasu's forces fought the army of Toyotomi Hideyoshi for control of the country. In 1598, Hideyoshi died of an illness, leaving a 5-year-old son as heir. In 1600, at the Battle of Sekigahara, Tokugawa forces dealt a death blow to the remnants of the Oda-Toyotomi alliance. From that moment on, he became the first shogun whose dynasty ruled Japan until the resurrection of the Meiji dynasty in 1868. The years of the Tokugawa clan left their mark on the country's development, isolating it from the rest of the world for a whole quarter of a millennium.

Tags:

MUGEN-RYU HEIHO

Katana sword owned by Tokugawa Ieyasu himself

In the samurai times in the Land of the Rising Sun there were many beautiful swords and many excellent masters who brilliantly mastered the art of swordsmanship. However, the most famous sword masters in the samurai tradition were Tsukahara Bokuden, Yagyu Mune-nori, Miyamoto Musashi and Yamaoka Tesshu.

Tsukahara Bokuden was born in Kashima, Hitachi Province. The first name of the future master was Takomoto. His own father was a samurai retainer of the daimyō of Kashima province and taught his son how to use the sword from early childhood. It seemed that Takamoto was a born warrior: while other children played, he practiced with his sword - first wooden, and then real, fighting. Soon he was sent to be raised in the house of the noble samurai Tsukahara Tosonoka-mi Yasumoto, who was a relative of the daimyo himself and brilliantly wielded a sword. He decided to transfer his art, along with his surname, to his adopted son. In him he found a grateful student who was determined to become a master on the "path of the sword."

The boy trained tirelessly and with inspiration, and his perseverance paid off. When Boku-den was twenty, he was already a master of the sword, although few people knew about it. and when a young man dared to challenge the famous warrior from Kyoto, Ochiai To-razaemon, many considered this a daring and rash trick. Ochiai decided to teach the impudent youth a lesson, however, to everyone's surprise, Bokuden defeated the eminent opponent in the very first seconds of the duel, but saved his life.

Ochiai was very upset by the shame of this defeat and decided to take revenge: he tracked down Bokuden and attacked him from an ambush. But the sudden and insidious attack did not take the young samurai by surprise. This time, Ochiai lost both his life and his reputation.

This duel brought Bokuden great fame. Many daimyo tried to get him as a bodyguard, but the young master rejected all these very flattering offers: he set out to further improve his art. For many years he led the life of a ronin, wandering around the country, learning from all the masters with whom fate confronted him, and fighting with experienced swordsmen. The times were then dashing: the wars of the Sengoku jidai era were in full swing, and Bokuden had to participate in many battles. He was entrusted with a special mission, both honorable and dangerous: he challenged enemy commanders (many of whom were first-class swordsmen themselves) to a duel and killed them in front of the entire army. Bokuden himself remained undefeated.

Pedinok on the roof of the temple

One of his most glorious duels was the duel with Kajiwara Nagato, who was reputed to be an unsurpassed master of the naginata. He also did not know defeat and was so skillful with weapons that he could cut a swallow on the fly. However, against Bokuden, his art was powerless: as soon as Nagato swung his halberd, Bokuden killed him with the first blow, which from the outside looked easy and simple. In fact, it was a virtuoso technique of hitotsu-tachi - a style of one blow, which Bokuden honed throughout his life.

The most curious "duel" of Bokuden was the incident that happened to him on Lake Biwa. Bokuden at that time was over fifty, he already looked at the world differently and did not want to kill people for the sake of meaningless glory. As luck would have it, in the boat, where Bokuden was among the other passengers, there was one frightening-looking ronin, stupid and aggressive. This ronin boasted of his swordsmanship, calling himself the best swordsman in Japan.

A boasting fool usually needs a listener, and the samurai chose Bokuden for this role. However, he did not pay any attention to him, and such disrespect infuriated the ronin. He challenged Bokuden to a duel, to which he calmly remarked that a true master seeks not to defeat, but, if possible, to avoid senseless bloodshed. Such an idea turned out to be indigestible for the samurai, and he, inflamed even more, demanded that Bokuden name his school. Bokuden replied that his school was called Mutekatsu-ryu, literally, "the school for achieving victory without the help of hands", that is, without a sword.

This angered the samurai even more. "What nonsense are you talking about!" he said to Bokuden, and ordered the boatman to dock at a tiny secluded island so that Bokuden could practically show him the advantages of his school. When the boat approached the island, the ronin was the first to jump ashore and draw his sword. Bokuden, on the other hand, took the pole from the boatman, pushed off from the shore and in one fell swoop took the boat away from the island. “This is how I achieve victory without a sword!” - said Bokuden and waved his hand to the fool left on the island.

Bokuden had three adopted sons, and he trained all of them in the art of the sword. Once he decided to give them a test and for this he placed a heavy block over the door. As soon as the door was opened, the log fell on the person entering. The eldest son was invited first by Bokuden. He sensed a catch and deftly picked up the block of wood that fell on him. When the block fell on the middle son, he managed to dodge in time and at the same time pull out the sword from the scabbard. When the turn came to the youngest son, he in the twinkling of an eye drew his sword and with a magnificent blow cut the falling log in half.

Bokuden was very pleased with the results of this "exam", because all three were on top, and the youngest also demonstrated excellent instant strike technique. However, Bokuden named his eldest son his main successor and the new head of his school, because in order to achieve victory he did not have to use the sword, and this most of all corresponded to the spirit of Bokuden's teachings.

Unfortunately, the Bokuden school did not outlive its founder. All his sons and best students died in battles against the troops of Oda Nobunaga, and there was no one left who could continue his style. Among the students was the shogun Ashikaga Yoshiteru himself, who brilliantly wielded a sword and worthily gave his life in an unequal battle with the killers surrounding him. Bokuden himself died in 1571 at the age of eighty-one. All that remains of his school are many legends and a book of one hundred verses known as the Bokuden Hyakushu. In the verses of the old master, it was about the path of the samurai, which runs along a thin line, like a sword point, separating life from death...

The one-hit technique developed by Bokuden and the idea of achieving victory without the help of a sword were brilliantly embodied in another school of ken-jutsu called Yagyu-Shinkage Ryu. The founder of the Shinka-ge school was the famous warrior Kamiizumi Nobutsuna, whose swordsmanship was appreciated by Takeda Shingen himself. His best student and successor was another famous swordsman, Yagyu Muneyoshi.

Miyamoto Musashi with two swords. From a painting by an unknown artist of the 17th century

Muneyoshi, who had achieved considerable skill even before meeting Nobutsuna, challenged him to a duel. However, Nobutsuna suggested that Muneyoshi fight first with bamboo swords with his student, Hikida Toyogoroo. Yagyu and Hikida met twice, and twice Hikida delivered swift blows to Yagyu, which he did not have time to parry. Then Nobutsuna himself decided to fight Yagyu Muneyoshi, who had suffered an obvious defeat, but when the opponents met their eyes, lightning seemed to strike between them, and Muneyoshi, falling at the feet of Nobutsuna, asked to be his student. Nobutsuna willingly accepted Muneyoshi and taught him for two years.

Muneyoshi soon became his best student, and Nobutsuna named him his successor, initiating all the secret techniques and all the secrets of his skill. Thus, the Yagyu family school merged with the Shinkage school, and a new direction arose, Yagyu-Shinkage Ryu, which became a classic in the art of ken-jutsu. The fame of this school spread throughout the country, and the rumor of the famous Yagyu Muneyoshi reached the ears of Tokutawa Ieyasu himself, who at that time was not yet a shogun, but was considered one of the most influential people in Japan. Ieyasu decided to test the already aged master, who said that a sword was not at all necessary to win a victory.

In 1594, Ieyasu invited Muneyoshi to his place to test his skills in practice. Among the bodyguards of Ieyasu there were many samurai who wielded a sword superbly. He ordered the best of them to try to cut down the unarmed Muneyoshi with a sword. But every time he managed to dodge the blade at the last moment, disarm the attacker and throw him to the ground so that the unfortunate crawled away on all fours or could not get up at all.

In the end, all the best bodyguards of Ieyasu were defeated, and then he decided to personally attack Muneyoshi. But when Ieyasu raised his sword to strike, the old master managed to duck under the blade and push its hilt with both hands. The sword, describing a sparkling arc in the air, fell to the ground. Having disarmed the future shogun, the master brought him to the throw. But he didn’t quit, only slightly “pressed”, and then politely supported Ieyasu, who had lost his balance. He recognized complete victory Muneyoshi and, admiring his skill, offered him the honorary position of personal fencing instructor. But the old master was about to leave for the monastery and offered instead of himself his son Munenori, who later also became a wonderful sword master.

Munenori was a fencing teacher both under the shogun Hidetada, son of Ieyasu, and under his grandson Iemitsu. Thanks to this, the Yagyu-Shinkage school soon became very famous throughout Japan. Munenori himself glorified himself in the battle of Sekigahara and during the assault on Osaka Castle - he was among the shogun's bodyguards and killed enemy soldiers who were trying to break through to Tokutawa's headquarters and destroy Ieyasu and his son Hideta-du. For his exploits, Munenori was elevated to the rank of daimyo, lived in honor and wealth, and left behind a lot of works on swordsmanship.

The Yagyu-Shinkage school paid special attention to the development of an intuitive sense of an approaching enemy, an unexpected attack, and other danger. The path to the heights of this art in the Yagyu-Shinkage tradition begins with comprehending the technique of the correct bow: as soon as the student lowered his head too low and stopped monitoring the surrounding space, he immediately received an unexpected blow to the head with a wooden sword. and so it went on until he learned to elude them without interrupting his bow.

In the old days, the art of the warrior was taught even more ruthlessly. In order to awaken in the student the qualities necessary for survival, the master fed him with slaps in the face 24 hours a day: he quietly sneaked up to him with a stick when he was sleeping or doing housework (usually the students in the master’s house did all the menial work), and beat him mercilessly. In the end, the student, at the cost of bumps and pain, began to anticipate the approach of his tormentor and think about how to avoid blows. From that moment on, a new stage of apprenticeship began: the master no longer took a stick in his hands, but a real samurai sword and taught already very dangerous fighting techniques, suggesting that the student had already developed the ability to think and act simultaneously and at lightning speed.

Some sword masters have perfected their art of zanshin to near-supernatural levels. An example of this is the samurai test scene in Kurosawa's Seven Samurai. The subjects were invited to enter the house, behind the door of which a guy was hiding with a club at the ready and unexpectedly hit the people on the head. One of them missed the blow, the others managed to dodge and disarm the attacker. But the samurai was recognized as the best, who refused to enter the house, because he sensed a catch.

Yagyu Munenori himself was considered one of the strongest zanshin masters. One fine spring day, he and his young squire admired the cherry blossoms in his garden. Suddenly, he began to feel that someone was preparing to stab him in the back. The master examined the entire garden, but found nothing suspicious. The squire, amazed at the strange behavior of the master, asked him what was the matter. He complained that he was probably getting old: he began to let down the feeling of zanshin - intuition speaks of danger, which in fact turns out to be imaginary. and then the guy admitted that, standing behind the back of the gentleman admiring the cherries, he thought that he could very easily kill him, inflicting an unexpected blow from behind, and then all his skills would not have helped Munenori. Munenori smiled at this and, pleased that his intuition was still on top, forgave the young man for his sinful thoughts.

Miyamoto Musashi fights against several opponents armed with spears

The shogun Tokutawa Iemi-tsu himself heard about this incident and decided to test Munenori. He invited him to his place supposedly for a conversation, and Munenori, as a samurai should, respectfully sat down at the feet of the ruler on a mat spread on the floor. Iemitsu spoke to him, and during the conversation, he suddenly attacked the master with a spear. But the movement of the shogun was not unexpected for the master - he managed to feel his "bad" intention much earlier than he carried it out, and therefore immediately made Iemitsu a cut, and the shogun was overturned, without having time to understand what had happened, and not swinging your weapon...

The fate of Yagyu Munenori's contemporary, the lonely warrior Miyamoto Musashi, who became the hero of samurai legends, turned out quite differently. He remained a restless ronin for most of his life, and in the battle of Sekigahara and in the battles at Osaka Castle he was on the side of the losing opponents of Tokutawa. He lived like a real ascetic, dressed in rags and despised many conventions. All his life he honed his fencing technique, but he saw the meaning of the “path of the sword” in comprehending the impeccability of the spirit, and this was what brought him brilliant victories over the most formidable opponents. Since Miyamoto Musashi shunned society and was a lone hero, little is known about his life. The real Miyamoto Musashi was eclipsed by his literary counterpart - the image derived in the popular adventure novel of the same name by the Japanese writer Yoshikawa Eji.

Miyamoto Musashi was born in 1584 in the village of Miyamoto, located in the town of Yoshino, Mima-saka province. His full name was Shinmen Musashi no kami Fujiwara no Genshin. Musashi was a master of the sword, as they say, from God. He took his first fencing lessons from his father, but honed his skills on his own - in exhausting training and dangerous duels with formidable opponents. Musashi's favorite style was nito-ryu - fencing with two swords at once, but he was no less deft with one sword and a jitte trident, and even used any means at hand instead of a real weapon. He won his first victory at the age of 13, challenging the famous sword master Arima Kibei, who belonged to the Shinto Ryu school, to a duel. Arima did not take this duel seriously, for he could not admit that a thirteen-year-old boy could become a dangerous opponent. Musashi entered the duel, armed with a long pole and a short wakizashi sword. When Arima tried to strike, Musashi deftly intercepted his hand, made a throw and hit with a pole. This blow was fatal.

At the age of sixteen, he challenged an even more formidable warrior, Tadashima Akiyama, to a duel and defeated him without much difficulty. In the same year, young Musashi participated in the Battle of Sekigahara under the banner of the Ashikaga clan, who opposed the Tokutawa troops. The Ashikaga detachments were utterly defeated, and most of the samurai laid down their violent heads on the battlefield; young Musashi was also seriously wounded and, most likely, should have died if he had not been pulled out of the thick of the battle by the famous monk Takuan Soho, who came out of the injured young man and had a great spiritual influence on him (as stated in the novel, although this, of course, artistic creation).

When Musashi was twenty-one years old, he went on a musya-shugo - military wanderings, looking for worthy opponents to hone his swordsmanship and take it to new heights. During these wanderings, Musashi wore dirty, torn clothes and looked very untidy; even in the bath he bathed very rarely, because one very unpleasant episode was connected with it. When Musashi nevertheless decided to wash himself and climbed into an o-furo, a traditional Japanese bath - a large barrel of hot water, then he was attacked by one of his opponents, who tried to take advantage of the moment when the famous warrior was unarmed and relaxed. But Musashi managed to “get out of the water dry” and defeat the armed enemy with his bare hands, but after this incident he hated swimming. This incident, which happened in the bath with Musashi, served as the basis for the famous Zen koan, asking what a warrior should do in order to defeat the enemies surrounding him, who caught him standing naked in a barrel of water and deprived not only of clothes, but also of weapons.

Sometimes sloppy looking Musashi try to explain his kind psychological cunning: misled by his worn dress, the rivals looked down on the tramp and were not ready for his lightning attacks. However, according to the testimony of the closest friends of the great warrior, from early childhood his entire body and head were completely covered with ugly scabs, so he was embarrassed to undress in public, could not wash in the bath and could not wear the traditional samurai hairstyle when half his head was shaved bald. Musashi's hair has always been disheveled and untidy, like a classic demon from Japanese fairy tales. Some authors believe that Musashi suffered from congenital syphilis, and this serious disease, which tormented the master all his life and eventually killed him, determined the character of Miyamoto Musashi: he felt different from all other people, was lonely and disfigured, and this disease , which made him proud and withdrawn, moved him to great achievements in the art of war.

For eight years of wandering, Musashi fought in sixty duels and emerged victorious from them, defeating all his opponents. In Kyoto, he had a series of brilliant duels with representatives of the Yoshioka clan, who served as fencing instructors for the Ashikaga family. Musashi defeated his older brother, Yoshioka Genzae-mon, and hacked his younger brother to death. Then he was challenged to a duel by the son of Genzaemon, Hanshichiro. In fact, the Yoshioka family intended, under the pretext of a duel, to lure Musashi into a trap, attack him with the whole crowd and kill him for sure. However, Musashi found out about this venture and himself ambushed behind a tree, near which the treacherous Yoshioka gathered. Suddenly jumping out from behind a tree, Musashi cut down Hanshichiro and many of his relatives on the spot, while the rest fled in fear.

Musashi also defeated such famous warriors as Muso Gonnosuke, the hitherto unsurpassed master of the pole, Shishido Baikan, who was reputed to be a master of kusari-kama, and the master of the spear monk Shuji, who was hitherto reputed to be invincible. However, the most famous duel of Miyamoto Musashi is considered to be his duel with Sasa-ki Ganryu, fencing teacher of the influential Prince Hosokawa Tadatoshi, the best swordsman in all of northern Kyushu. Musashi challenged Ganryu to a duel, the challenge was readily accepted and received the approval of the daimyo Hosokawa himself. The duel was scheduled for the early morning of April 14, 1612 on the small island of Funajima.

The first blow is the final blow!

At the appointed time, Ganryu arrived at the island with his men, he was dressed in a scarlet haori and hakama and girded with a magnificent sword. Musashi, on the other hand, was late for several hours - he frankly overslept - and all this time Ganryu nervously walked back and forth along the coast of the island, acutely experiencing such humiliation. Finally, the boat brought Musashi too. He looked sleepy, his clothes were wrinkled and tattered like a beggar's rags, his hair was matted and tousled; as a weapon for the duel, he chose a fragment of an old oar.

Such a frank mockery of the rules of good manners infuriated the exhausted and already angry opponent, and Ganryu began to lose his cool. He drew his sword with lightning speed and furiously aimed a blow at Musashi's head. At the same time, Musashi hit Ganryu on the head with his piece of wood, stepping back. The lace that tied his hair turned out to be cut by a sword. Ganryu himself fell to the ground, unconscious. Recovering his senses, Ganryu demanded the continuation of the duel, and this time, with a deft blow, he managed to cut through his opponent's clothes. However, Musashi defeated Ganryu on the spot, he fell to the ground and did not get up again; blood gushed from his mouth, and he immediately died.

After the duel with Sasaki Ganryu Musashi has changed a lot. Duels no longer appealed to him, but he became passionate about Zen painting in the Suiboku-ga style and gained fame as an excellent artist and calligrapher. In 1614-1615. he participated in the battles at Osaka Castle, where he showed miracles of courage and military skill. (It is not known, however, on whose side he fought.)

For most of his life, Musashi wandered around Japan with his adopted son, and only at the end of his life agreed to serve the daimyō Hosokawa Tadatoshi, the same one whom the late Ganryū had once served. However, Tadatoshi soon died, and Musashi left the Hosokawa house, becoming an ascetic. Before his death, he wrote the now famous "Book of Five Rings" ("Go-rin-no shu"), in which he reflected on the meaning of martial arts and the "way of the sword." He died in 1645, leaving a memory of himself as a sage and philosopher who went through fire, water and copper pipes.

Any tradition - including the tradition of martial arts - knows periods of prosperity and decline. History knows many examples when, due to various circumstances, traditions were interrupted - for example, when the master did not know to whom to transfer his art, or the society itself lost interest in this art. It so happened that in the first decades after the Meiji restoration, Japanese society, carried away by restructuring in a European way, lost interest in its own national tradition. Many beautiful groves, once glorified by poets, were ruthlessly cut down, and factory buildings smoky with chimneys arose in their place. Many Buddhist temples and ancient palaces were destroyed. The survival of the traditions of samurai martial arts was also threatened, for many believed that the era of the sword had irrevocably passed, and sword exercises were a completely pointless waste of time. Nevertheless, the samurai tradition, thanks to the asceticism of many masters, managed to survive and find a place for itself in the transformed Japan, and even splashed out beyond its borders.

One of these masters, who saved the noble art of the sword from extinction, was Yamaoka Tesshu, whose life fell on the period of the fall of the Tokutawa regime and the sunset of the "golden age" of the samurai. His merit lies in the fact that he managed to lay the bridge on which the samurai martial arts passed into a new era. Yamaoka Tesshu saw the salvation of the tradition in making it open to representatives of all classes who wish to dedicate their lives to the "path of the sword."

Master Yamaoka Tesshu was born in 1835 into a samurai family and, as usual, he received his first sword skills from his father. He honed his skills under the guidance of many masters, the first of which was the famous swordsman Chiba Shusaku, the head of the Hokushin Itto Ryu school. Then Tesshu, at the age of 20, was adopted into the Yamaoka samurai family, whose representatives from generation to generation were famous for the art of the spear (soojutsu). Having married the daughter of the head of this family, Tesshu took the surname Yamaoka and was initiated into the innermost secrets of the family school of swordsmanship.

Combining all the acquired knowledge and inspired by Zen ideas, Tesshu created his own style of swordsmanship, calling it Muto Ryu - literally, "style without a sword"; to his own hall for fencing exercises, he gave the poetic name “Syumpukan” (“Hall of the Spring Wind”), borrowed from the poems of the famous Zen master Bukko, who lived in the 13th century, the very one who helped Hojo Tokimune repel the Mongol invasion. By the way, the image of the wind - fast, knows no barriers and can instantly turn into an all-destroying hurricane - has become one of the most important mythologies that reveal the image of a sword master that has developed over the centuries.

In his twenties, Tesshu became famous for his brilliant victories over many skilled swordsmen. However, he had one opponent, from whom Tesshu was constantly defeated, - Asari Gimei, the head of the Nakanishi-ha Itto Ryu school. Tesshu eventually asked Asari to be his teacher; he himself trained with such perseverance and ruthlessness to himself that he received the nickname Demon. However, despite all his tenacity, Tesshu could not defeat Asari for seventeen years. At this time, the Tokutawa shogunate fell, and in 1868 Tesshu participated in the hostilities of the "Boshin War" on the side of the Bakufu.

Zen Buddhism helped Tesshu to rise to a new level of mastery. Tesshu had his mentor, the Zen master monk Tekisui of the Tenryu-ji temple. Tekisui saw the reason for Tesshu's defeats in the fact that he was inferior to Asari not so much in swordsmanship (he had it honed to the limit), but in spirit. Tekisui advised him to meditate on this koan: “When two sparkling swords meet, there is nowhere to hide; be coldly calm, like a lotus flower blooming in the midst of a raging flame and piercing the Heavens! Only at the age of 45 Tesshu managed to comprehend in meditation the secret, inexpressible in words, the meaning of this koan. When he again crossed swords with his teacher, Asari laughed, threw away his blade and, congratulating Tesshu, called him his successor and the new head of the school.

Tesshu became famous not only as a master of the sword, but also as an outstanding mentor, who left behind many students. Tesshu liked to say that he who comprehends this art of the sword comprehends the essence of all things, for he learns to see both life and death at the same time. The master taught his followers that the true purpose of sword art is not to destroy the enemy, but to forge one's own spirit - only such a goal is worth the time spent on achieving it.

This philosophy of Tesshu was reflected in the system of so-called seigan developed by him, which is still widely used in various Japanese traditional martial arts. Seigan in Zen Buddhism means a vow that a monk gives, in other words, a severe test in which strength of mind is manifested. According to the Tesshu method, the student had to train continuously for 1000 days, after which he was admitted to the first test: he had to fight 200 fights in one day with only one short break. If the student passed this test, then he could pass the second, more difficult one: in three days he had to participate in three hundred fights. The third, final test involved going through 1,400 fights in seven days. Such a test went beyond the usual understanding of swordsmanship: in order to withstand such a load, just mastering the technique of fencing was not enough. The student had to combine all his physical strength with the strength of the spirit and achieve a mighty intention to pass this test to the end. Those who passed such an exam could rightfully consider themselves a real samurai of the spirit, which was Yamaoka Tesshu himself.