Elena Glinskaya interesting facts. Elena Glinskaya - reforms. Elena Vasilievna Glinskaya, mother of Ivan the Terrible. Monetary reform of Elena Glinskaya. The last will of Vasily III

The mother of Ivan IV (the Terrible) Elena Glinskaya is rarely mentioned today. But the story of her life is inextricably linked with Russia. Thanks to the efforts of this female ruler, the state was able to survive without irreversible damage ...

The mother of Ivan IV (the Terrible) Elena Glinskaya is rarely mentioned today. But the story of her life is inextricably linked with Russia. Thanks to the efforts of this female ruler, the state was able to survive the time of unrest and rebellion without irreversible damage.

The Glinskys are considered descendants of the famous Khan Mamai. After the victory of the Russians on the Kulikovo field, one of the clan of Khan Mamai, having converted to Orthodoxy, began to serve the Lithuanian prince. Subsequently, he received the title of Prince Glinsky. In terms of nobility, the Glinsky family was second only to the reigning dynasties.

The Glinskys ended up in Russia thanks to Prince Mikhail Lvovich Glinsky, who was called to the service by the Russian Tsar, offering a large salary, help to him and his close relatives. Therefore, Prince Glinsky brought his family with him to a new place of residence. And indeed, the sovereign kept his promise and endowed Glinsky with lands and even two cities (Medyn, Yaroslavl). Unfortunately, the prince did not get along on Russian soil and wanted to return to Lithuania. But that was not the case: he was immediately imprisoned for a long time, accused of betrayal.

It is not known for sure whether Elena Glinskaya was born in Moscow or was brought as a child. It is known for certain that she met Tsar Vasily III at the age of eighteen. Elena Glinskaya possessed not only amazing beauty, but was also smart, received an excellent education: she spoke Polish, German knew Latin. Vasily III was delighted with the young Elena. Why the king chose Elena as his wife is unknown. But her candidacy was quite suitable for the closest associates of the sovereign: the family of the future tsarina was not connected by ties with any boyar clans. The king needed an heir, and Elena always dreamed of taking a higher position in society. And as subsequent events showed, the sovereign sincerely fell in love with his young wife. For the sake of young Elena, the tsar changed many established customs, bringing them closer to European fashion. It cannot be said that the environment was against such changes. Many liked to shave their beards, wear European clothes, adorn themselves with jewels and use incense.

The first wife of Vasily III was unable to give birth to an heir. And this led to a divorce. They say that the Tsar ordered to build the Novodevichy Convent for her. Four months after the tonsure of his first wife as a nun, Vasily III married Elena Glinskaya.

Despite the marriage of the sovereign to Elena, the fate of Mikhail Lvovich Glinsky did not immediately change - he was still in prison. Only the persistent requests of his wife could soften the heart of the king, and he gave freedom to the captive and introduced him into his environment.

The closest associate of the king at that time was considered to be Prince Ivan Telepnev-Obolensky. A handsome man, a wonderful military leader did not take his eyes off the young queen in love. Over time, he will become the closest person to Elena.

In the meantime, in all churches it is ordered to pray that the Lord would grant the reigning couple an heir. The spouses themselves also made pilgrimage to monasteries to miraculous icons, attended church services and gave gifts to the poor. The heir was born only four years later, after the wedding in 1530. Everyone was sure that this long-awaited event happened due to the intervention of divine forces. They baptized the first-born in the Trinity-Sergius Monastery and named John. The nurse of the baby was the sister of Prince Obolensky.

Vasily III dearly loved and cared for his son. Even when he was away from Moscow, he constantly demanded to report to him about the boy's health.

Soon the second son, Yuri, was born in the royal family. And five weeks after this joyful event, Vasily III fell ill and died: according to the official version, from blood poisoning.

After the death of the sovereign, Elena Glinskaya found herself in a difficult situation: her son Ivan had not reached the age when it was possible to take the Russian throne, and she was considered a foreigner and the daughter of a Lithuanian governor, whom the sovereign accused of betrayal. She did everything possible to secure her son's right to the throne. A ceremony was held to declare the young Ivan the Grand Duke. Messengers were sent around the cities with orders to swear allegiance to the new Grand Duke.

Open opponents of Elena Glinskaya and her son were her husband's brothers, who were hampered by the Board of Trustees, who ruled on behalf of the minor sovereign. This council was created during the life of Vasily III and no one could influence its activities, including Elena Glinskaya herself. The young ruler needed serious support. And it was provided by Ivan Telepnev-Obolensky. Until now, the reason for such a rapprochement between the famous governor and the ruler remains a mystery. Perhaps the governor's sister and at the same time the nanny of the young Ivan Vasilyevich played a role in this, or there had long been a love affair between the tsarina and the nobleman during the life of Vasily III. Whatever the reason, Telepnev and Elena ended up together in this historical period, soldered together by one fate.

In order to keep the throne for her son, Elena Glinskaya took harsh measures against those who hatched plans to prevent Ivan from the Russian throne. She physically destroyed her opponents. The uncle of the ruler, Mikhail Glinsky, who did not accept the fact that Elena interfered in government and reproached her for cohabitation with Telepnev-Obolensky, also fell under reprisal. The ruler hid her relative in prison, and after him she deprived all members of the guardianship council of power. Only the Shuiskys and the brother of Vasily III, Andrei Staritsky, survived, who did not interfere with Elena's rule and lived quietly in Moscow. But, as it turned out, not for long. Andrei Staritsky demanded from Elena the city for his inheritance, having received a refusal, he fled from Moscow, fearing for his life. Being a refugee, Andrey began to be perceived by Elena and her governor Obolensky as a threat. Andrei Staritsky was caught and imprisoned. The same fate befell the wife and son of the disgraced prince.

Simultaneously with the internal struggle, the ruler also waged external wars. Troops led by Obolensky attacked the Polish and Lithuanian lands, as a result of victories and defeats, it was possible to conclude a temporary truce. The weakening of power led to the fact that Kazan attacked the Russian estates. It was not possible to take revenge on the Kazanians for the robbery of the Kostroma district: the Crimean Khan threatened Moscow. Six-year-old Ivan had to receive Kazan ambassadors and offer peace.

Elena Glinskaya managed the state as best she could. New fortresses appeared on the borders of Russia, and the old ones were strengthened anew. Three hundred families of refugees from Lithuania were placed on Russian lands. There was a fight against counterfeiters, and a new coin was introduced into use, on which the heir to the throne, Ivan, is depicted with a spear in his hand (penny). Kitai-gorod was being built up and fortified.

It seemed to Elena that life was gradually returning to a calm course: internal enemies were destroyed, and external ones did not bother ... Her unexpected death in April 1538 surprised everyone. The annals state that the Grand Duchess was poisoned by the boyars who hated her. Until now, no one can explain why Elena Glinskaya was buried the very next day and why there is no mention that the metropolitan held a funeral ceremony over the body of the ruler. Neither the people nor the boyars expressed grief for the deceased princess. Only the little son and Prince Obolensky mourned Elena Glinskaya.

Seven days after the death of the Grand Duchess, the boyar council, ruled by Shuisky, decided to imprison Prince Obolensky, where he soon died of hunger and cold. Russia for a long time passed into the hands of various boyar groups. Only Ivan Vasilyevich changed the situation. Having entered the reign of the country, he burned his enemies with "blood and iron."

Until now, it is doubtful that Ivan IV was the son of Vasily III. For contemporaries, the close relationship between Elena Glinskaya and Obolensky was not a secret, so Ivan the Terrible could well be the son of the governor Telepnev-Obolensky. Perhaps the difficult years of childhood, the loss of parents were deposited on the character of the future Russian tsar. Ivan IV (the Terrible) remained in the memory of generations as the most cruel ruler, who did not disdain the most barbaric methods of government.

But his mother remained a bright memory, because although she was from the Principality of Lithuania, but becoming the Russian queen, she showed herself as a real patriot of the new homeland.

Vasily III grieved greatly that he had no children. They say that once he even cried when he saw a bird's nest with chicks on a tree.

- Who will reign after me in the Russian land? he mournfully asked his neighbors. - My brothers? But they can't even manage their own business!

On the advice of those closest to him, he divorced his first wife, Solomonia Saburova, who was tonsured, as they say, against her desire, and, as mentioned above, married Elena Glinskaya, the niece of the famous Mikhail Glinsky.

Solomonia Saburova. Painting by P. Mineeva

The new wife of Vasily III was not like the then Russian women: her father and especially her uncle, who lived in Italy and Germany, were educated people, and she also learned foreign concepts and customs. Vasily III, having married her, seemed to be inclined towards rapprochement with Western Europe. To please Elena Glinskaya, he even shaved off his beard. This, according to the then concepts of the Russians, was considered not only an obscene deed, but even a grave sin: the Orthodox considered a beard an essential accessory of a pious person. On the icons representing the Last Judgment, on the right side of the Savior, the righteous were depicted with beards, and on the left, infidels and heretics, shaved, with only mustaches, “like cats and dogs,” pious people spoke with disgust.

Despite such a view, young dandies appeared in Moscow at that time, who tried to become like women and even plucked their hair on their faces, dressed up in luxurious clothes, put shiny buttons on their caftans, put on necklaces, many rings, rubbed themselves with various fragrant ointments, went around in a special way. small step. Pious people armed themselves strongly against these dandies, but they could not do anything with them. Having married Elena Glinskaya, Vasily III began to flaunt ...

Elena Glinskaya. Reconstruction from the skull of S. Nikitin

Papa found out that the Grand Duke was deviating from the old Moscow customs and was trying to persuade him to the union - Vasili filed. III, even the hope of getting Lithuania after the childless Sigismund, also hinted at the fact that Constantinople, “the fatherland of the Moscow sovereign,” could be taken over. Basil III expressed a desire to be in alliance with the pope, but evaded negotiations on church affairs.

More than four years have passed since his marriage to Elena Glinskaya, and Vasily Ivanovich still had no children. He and his wife went on a pilgrimage to the monasteries, distributed alms; in all Russian churches they prayed for the granting of an heir to the sovereign.

Finally, on August 25, 1530, Elena Glinskaya gave birth to an heir, Vasily III, who was named John at baptism. Then there was a rumor that when he was born, a terrible thunder swept across the Russian land, lightning flashed and the earth trembled ...

One holy fool predicted to Elena Glinskaya that she would have a son, "Titus - a broad mind."

Two years later, Vasily III and Elena had a second son, Yuri.

The reforms of Elena Glinskaya were carried out in conditions when the young united Russian state changed its way of life, abandoning the outdated orders of the period of fragmentation.

Personality of Elena Glinskaya

In 1533, Grand Duke Vasily III died suddenly. His first wife was never able to bear him a child. Therefore, quite shortly before his death, he concluded his own despite the fact that it was contrary to church rules. His second wife was Elena Glinskaya. As in any monarchy, in the Moscow principality, in the absence of an heir, the question of the succession of power sharply arose. Because of this, the personal life of the ruler became an invariable part of public life.

Elena gave birth to Vasily two sons - Ivan and Yuri. The eldest of them was born in 1530. At the time of his father's death, he was only three years old. Therefore, a regency council was assembled in Moscow, which included boyars from various influential aristocratic families.

Board of Elena Glinskaya

Elena Vasilievna Glinskaya, the mother of the young prince, stood at the head of the state. She was young and full of energy. According to law and tradition, Elena was supposed to transfer power to her son when he reached the age of majority (17 years).

However, the regent died suddenly in 1538 at the age of 30. Rumors circulated in Moscow that she had been poisoned by the Shuisky boyars, who wanted to seize all power in the council. One way or another, but the exact causes of death have not been clarified. Power for another decade passed to the boyars. It was a period of unrest and excesses, which influenced the character of the future king.

Nevertheless, in the short period of her reign, Elena managed to implement many state changes that were designed to improve life within the country.

Prerequisites for monetary reform

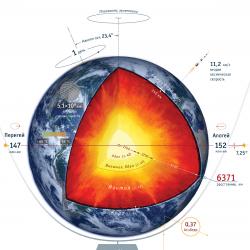

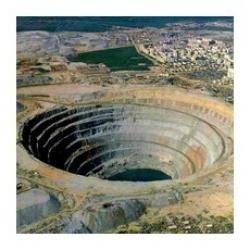

In 1535, an unprecedented transformation of the monetary system began, initiated by Elena Glinskaya. Reforms have been needed for decades. Under Ivan III and Vasily III, it annexed many new sovereign territories of Pskov, the Ryazan principality, etc.). Each region had its own currency. Rubles differed in denomination, coinage, share of precious metals, etc. While the specific princes were independent, each of them had his own mint and determined the financial policy.

Now all the scattered Russian lands were under the jurisdiction of Moscow. But the mismatch of money led to the complication of interregional trade. Often, the parties to the transaction simply could not settle among themselves due to the discrepancy between their coins. This chaos could not remain without consequences. Counterfeiters were caught all over the country, who flooded the market with low-quality fakes. There were several methods of their work. One of the most popular was circumcision of coins. In the 1930s, the amount of low-quality money became threatening. The execution of criminals did not help either.

The essence of the changes

The first step towards correcting the financial situation was to be a ban on the monetary regalia (the right to mint) of the former free appanages, on the territory of which their own mints existed. The essence of the monetary reform of Elena Glinskaya - the whole

At this time, the number of European merchants increased, who happily traveled to trade in the markets of Muscovy. There were many goods rare for Western buyers (furs, metals, etc.) in the country. But the growth of trade was hampered by the turmoil with counterfeit coins within the Moscow principality. The monetary reform of Elena Glinskaya was supposed to correct this situation.

Continuation of the policy of Basil III

It is interesting that measures to change the monetary policy were discussed even under Vasily III. The prince led an active foreign policy (fought with Lithuania, Crimea, etc.). The cost of the army was reduced due to the deliberate deterioration of the quality of coins, in which the proportion of precious metals decreased. But Vasily III died prematurely. Therefore, the monetary reform of Elena Glinskaya took place in unexpected circumstances. The princess successfully coped with her task in a short time. This can only be explained by the fact that she was an active assistant in Vasily's affairs when he was still alive. That is why Elena Glinskaya was aware of all the cases and the necessary measures. The confusion inside and the regency council could not prevent the young ruler.

Reform implementation

In February 1535, a decree on changes in monetary circulation was announced in Moscow. Firstly, all old coins that had been minted up to that day became invalid (this applied to both low-grade fakes and coins of the corresponding quality). Secondly, new money was introduced weighing a third of a gram. For the convenience of small calculations, they also began to mint coins twice as light (0.17 grams). They were called polushki. At the same time, the word of Turkic origin "money" was officially fixed. Initially, it was distributed among the Tatars.

However, there were also reservations that provided for the monetary reform of Elena Glinskaya. In short, some exceptions were introduced for Veliky Novgorod. It was this city that was the merchant capital of the principality. Merchants from all over Europe came here. Therefore, for ease of calculation, Novgorod coins received their own weight (two-thirds of a gram). They depicted a rider armed with a spear. Because of this, these coins began to be called kopecks. Later this word spread throughout Russia.

Effects

It is difficult to overestimate the benefits brought by the reforms of Elena Glinskaya, which are very difficult to describe briefly. They helped the country move to a new stage of development. A unified monetary system facilitated and accelerated trade. Rare goods began to appear in distant provinces. The food shortage has decreased. Merchants grew rich and invested their profits in new projects, raising the country's economy.

The quality of coins minted in Moscow has improved. Among European merchants began to be respected international trade country, which allowed the sale of rare goods abroad, which gave a significant profit to the treasury. All this was facilitated by the reforms of Elena Glinskaya. The table shows the main features of these transformations not only in the financial, but also in other spheres of society.

lip reform

Princess Elena Glinskaya, whose reforms did not end with finances, also began to change the system of local government. The change in the borders of the state under her husband led to the fact that the old internal Administrative division became ineffective. Because of this, the lip reform of Elena Glinskaya began. It concerned local government. The adjective "labial" comes from the word "ruin". The reform also covered criminal justice in the province.

According to the innovation of the princess, labial huts appeared in the country, in which labial elders worked. Such bodies were to begin work in each volost city. The labial elder could conduct a trial over the robbers. This privilege was taken away from the feeders, who appeared during the growth of the Moscow principality. The boyars who lived outside the capital became not just governors. At times their power was too dangerous for the political center.

Therefore, the transformations in local self-government began, initiated by Elena Glinskaya. The reforms also introduced new territorial districts (lips), which corresponded to the territory that was under the jurisdiction of the lip elders. It was a division according to criminal jurisdiction. It did not cancel the usual volosts, which corresponded to the administrative boundaries. The reform began under Elena and continued under her son Ivan. In the 16th century, the borders of the lips and volosts coincided.

Changes in local government

The elders were chosen from local boyars. They were controlled by the Duma, which met in the capital, as well as the Rogue Order. This governing body was in charge of criminal cases of robberies, robberies, murders, as well as the work of prisons and executioners.

The division of powers between the local administration and the judiciary made it possible to increase the efficiency of their work. The position of a lip kisser also appeared. He was elected from among wealthy peasants and had to help the headman in his work.

If the criminal case could not be considered in the lab hut, then it was sent to the Robbery order. All these innovations have been brewing for a long time, but they appeared precisely at the time when Elena Glinskaya ruled. The reforms have made it safer for merchants and travelers to travel on the roads. New system useful in the improvement of the Volga lands annexed at the time (Kazan and Astrakhan khanates).

Also, the mouth huts helped the authorities to fight against anti-government protests among the peasantry. As mentioned above, the reform was necessary not only to change local government, but also to combat feeding. The abandonment of this outdated practice occurred a little later, when, under the successors of Elena, they began to update the Zemstvo legislation. As a result, over time, the appointed governors were replaced by elected ones, who knew their volost better than the appointees from Moscow.

The work of the labiums

The appearance of labial huts and the beginning of an organized fight against crime were the result of understanding that any violation of the law is not a private matter of the victim, but a blow to the stability of the state. After Elena Glinskaya, the criminal norms were also updated in her son's Code of Laws. Each labial headman received a staff of employees (tsolovalnikov, tenths, etc.). Their number depended on the size of the bay and the number of residential yards within this territorial unit.

If before that the feeders were engaged only in the adversarial and accusatory process, then the elders conducted search and investigative activities (for example, interviewing witnesses, searching for evidence, etc.). It was a new level of legal proceedings, which made it possible to more effectively fight crime. The reforms of Elena Glinskaya became an unprecedented impetus in this sphere of society.

“The Dowager Kingdom” [Political crisis in Russia in the 30s–40s of the 16th century] Krom Mikhail Markovich

1. Death of Elena Glinskaya

1. Death of Elena Glinskaya

With the death of Prince Andrei Staritsky, the dynastic problem ceased to disturb the guardians of the young Ivan IV: the real contenders for the grand prince's throne in the person of the brothers of the late Vasily III were physically eliminated. But the "treatment" turned out to be no better than the "disease" itself. As shown in the previous chapter, the repressive measures repeatedly resorted to by the Grand Duchess during the several years of her reign seriously narrowed her support base in the court environment. Numerous relatives of the disgraced and executed could not have good feelings for the ruler and her favorite. The treacherous reprisal against the staritsa prince - in violation of the kiss of the cross - apparently caused condemnation in society.

Moods of this kind were reflected in the news from Russia, which were recorded in Livonia in the autumn of 1537. The above-mentioned Margrave Wilhelm of Brandenburg, having informed his brother, Duke of Prussia Albrecht, in a letter dated November 6 of that year, about the imprisonment of Prince Andrei in prison after an agreement with the regent of the young Grand Duke sealed with a kiss of the cross, further told that “this treason (untrew) was repaid Muscovites Tatars - looting and devastation of many lands, castles (Schlosser) and cities, as well as ... the withdrawal of people and property (volk und guttern)", "repaid on such a scale (der masenn vorg?ldenn), which no one has been talking about for many years heard."

In the above message, the invasion of the Tatars looks like God's punishment, like a punishment sent down from above to the country for the treachery of its rulers. It is quite possible, however, that such an interpretation of events belongs to the coadjutor of the Archbishop of Riga himself. But the "true news" (gewisse zeitungenn) from Muscovy, which he retells in his letter, of course, contained not only facts, but also their assessment. If some chroniclers, as we remember, wrote reproachfully about the ruler’s obvious treachery, then in conversations, it must be assumed, there were much sharper judgments about the actions of the Grand Duchess and Prince Ivan Ovchina Obolensky, including, perhaps, fears of God's wrath.

The attitude towards the ruler was even more prominent in the reaction to her death, which occurred on April 3, 1538.

The last event in the life of the Grand Duchess, which is mentioned in the official chronicle, was a trip with children on a pilgrimage to the Mozhaisk Nikolsky Cathedral, which, apparently, enjoyed the special attention of the ruler: a letter of commendation issued on December 16, 1536 was preserved (in the list of the 17th century). on behalf of the Grand Duke to Archpriest St. Nicholas Cathedral in Mozhaisk Athanasius. Elena Vasilievna with her sons Ivan and Yuri left Moscow on January 24, 1538; “Having listened to the prayer service and divine litorgy and signing herself at the holy image” in St. Nicholas Cathedral, on January 31 she returned to the capital.

Further, the chronicle speaks of the return of the Grand Duke's envoys from the Crimea and Lithuania, as well as the arrival of the Turkish embassy. Against this everyday background, the following chronicle article, entitled "On the Repose of the Grand Duchess," looks completely unexpected.

Noteworthy is the brevity of the early annalistic news about the death of Elena Glinskaya. So, the Resurrection Chronicle reports: “In the summer of 7046, April 3, on Wednesday, the fifth week of Holy Lent, at 2 o’clock in the afternoon, the blessed Grand Duke Vasily Ivanovich reposed, the blessed Grand Duchess Elena, Prince Vasiliev’s daughter Lvovich Glinsky; and it was supposed to be in the Church of the Ascension of our Lord Jesus Christ, near Grand Duchess Sophia of Grand Duke Ivan Vasilyevich.

Even shorter is the message of the Postnikovsky chronicler, who names a different date for the death of the ruler: “In the summer of April 7046, on the 2nd day, the Grand Duchess Elena reposed in memory of the reverend father of our confessor Nikita, hegumen of Nicomedia, from Tuesday to Wednesday at 7 o’clock ours. And it was supposed to be in Ascension.

Only in the 50s. 16th century appears something like an obituary to the Grand Duchess. Taking as a basis the news of the Resurrection Chronicle about the repose on April 3 (it was this date that was confirmed in the annals) of “blessed Grand Duchess Elena”, the compiler of the Chronicler of the beginning of the kingdom supplemented this short message a kind of summing up the four-year reign of the widow of Vasily III: “And after the husband of her Grand Duke Vasily Ivanovich of All Russia with her son with the Grand Duke Ivan Vasilyevich of All Russia, and the power ruled the state of great Russia for four years and four months, for the sake of being young, the Grand Duke To Ivan Vasilyevich, her son, who has come one hundred years from his birth. The chronicler ends his story with a mention of the burial of Elena Vasilievna in the Ascension Monastery, in the tomb of the Grand Duchesses, next to the tomb of Sophia, the wife of Ivan III.

One gets the impression that the death of the ruler was sudden: in any case, the chroniclers do not mention a word about any illness that preceded the death of the Grand Duchess. True, R. G. Skrynnikov sees indirect evidence of her illness in Elena’s frequent trips on pilgrimage: “From 1537,” the scientist writes, “the Grand Duchess began to diligently visit monasteries for the sake of pilgrimage, which indicated a deterioration in her health.” Indeed, in that year she twice (in June and at the end of September) went with her sons to the Trinity-Sergius Monastery. But these trips can be given a completely different explanation, without resorting to a dubious version (not supported by any sources) about a long illness from which the Grand Duchess allegedly suffered.

The fact that in the first years of her reign the young widow did not leave the capital is probably due to her concern for her sons, the youngest of whom, Yuri, was barely a year old by the time of the death of his father, Vasily III. The Grand Duchess obviously did not dare to leave the princes in the care of their mothers (recall the disturbing atmosphere of the summer of 1534 described in the second chapter of this book, rumors about the death of both boys, etc.), and traveling with small children in her arms was a risky business. Only when the sons grew up a little did pilgrimage trips begin: the chronicle specifically notes the first such trip, to the Trinity-Sergius Monastery, on June 20, 1536. It was short: two days later the grand ducal family, accompanied by the boyars, returned to Moscow.

It is no coincidence that the monastery of St. Sergius became the object of pilgrimage: here, on September 4, 1530, Vasily III baptized his first-born. Beginning in 1537, young Ivan IV with his brother invariably went every year in September to the Trinity Monastery - "to pray to the memory of miracles." Often he visited the Trinity twice a year (in this case, usually, in addition to September, also in May - June).

Thus, there was nothing unusual in the visit of Elena Glinskaya with her children to the Trinity Monastery in June and September 1537: such trips were already becoming a tradition in the grand ducal family. On the other hand, perhaps, an “unscheduled” trip to Mozhaisk at the end of January 1538 was dictated by concern about health - “to pray to the image of the holy great miracle worker Nikola”. But even if we connect this pilgrimage with the deteriorating health of the empress (and, as already mentioned, we do not have direct evidence of this), then we must admit that the illness of the Grand Duchess was transient: two months later Elena Vasilievna died.

The death of the ruler, who was not even thirty years old, gave rise to rumors about her poisoning. This version of events is well known to historians in the presentation of Sigismund Herberstein. In his famous “Notes on Muscovy”, an Austrian diplomat, reporting the death of Prince Mikhail Glinsky in prison, adds: “... according to rumors, the widow [Elena. - M. K.] a little later she was put to death with poison, and her sheepskin seducer was cut into pieces. In the Latin edition of the Notes (1549), the poisoning of the Grand Duchess is mentioned twice: first in the chapter on Moscow court ceremonies, and then in almost the same words - in the section "Chorography".

R. G. Skrynnikov drew attention to the changes made by Herberstein to the German edition of his book (1557): in particular, the news of the poisoning of Elena Glinskaya was removed there, which, according to the historian, is explained by the fact that the author of the Notes to At that time, "I became convinced ... of the unfoundedness of the rumor." It is doubtful, however, that eighteen years after the death of the ruler, Herberstein could have received any new information that refuted the previous rumors about the poisoning of the Grand Duchess. In addition, the 1557 edition does not completely remove the news that interests us: in the chapter on ceremonies, there is indeed no mention of Elena's death from poison, but it is left unchanged in the Chorografie.

Herberstein traveled to Poland in September 1539 and made numerous visits to that country in subsequent years. It is natural to assume that he learned about the April events of 1538 in Moscow from Polish dignitaries. We can judge about the information on this subject at the court of Sigismund I from the letter of Stanislav Gursky, secretary of Queen Bona, addressed to Clement Janitsky, a student at the University of Padua. This letter, dated June 10, 1538, has come down to us in one of the handwritten volumes of the collection of diplomatic documents compiled by Gursky and later called "Acta Tomiciana". Among other news, Gursky told the Padua schoolboy the following news: Grand Duke Moscow is blinded (Dux Moschorum magnus caecus factus est), and his mother, the Grand Duchess, is dead (mater vero sua dux etiam magna mortua est). God punished for the treachery of those who villainously killed their uncles and relatives-princes (patruos et consanguineos suos Duces) in order to more easily seize power (per scelus ingularunt).

The above message is not interesting because of the facts contained in it (the rumor about the blinding of Ivan IV turned out to be false, of course), but by their interpretation: the death of the Grand Duchess and the misfortune that befell her son are considered as God's punishment for the crimes they committed. “Uncles and relatives-princes” are, of course, Andrei Staritsky, Yuri Dmitrovsky, and also Mikhail Glinsky (the uncle of the Grand Duchess).

The idea of retribution is also present in the story of Herberstein, who lays the blame for the death of the three princes mentioned precisely on Elena Glinskaya; this motif of retribution is especially noticeable in the section "Chorography": "A little later," writes an Austrian diplomat, "the cruel one herself died from poison."

The theme of inevitable retribution for the cruelty and treachery of the Moscow rulers runs like a red thread through the reports of foreign contemporaries discussed above about the events in Russia at the end of the 1530s. This theme is heard in the message of Margrave Wilhelm to Duke Albrecht of Prussia dated November 6, 1537, and in the work of Herberstein, and in the letter of Gursky to K. Janitsky dated June 10, 1538. The key question is, of course, whether the mentioned comments, at least to some extent, on the mood that existed then in Russia itself, or before us are only examples of the moralizing characteristic of educated Europeans of the 16th century.

We have at our disposal several direct and indirect evidence of domestic origin, which unambiguously speak of the relationship of the court elite to the late ruler. First of all, it is worth quoting the words of Ivan the Terrible from the message to Andrei Kurbsky, in which the tsar, denouncing the wickedness of his opponent’s ancestors, in particular the boyar M.V. Tuchkov, wrote: “... so is your grandfather [Kurbsky. - M. K.], Mikhailo Tuchkov, at the death of our mother, the great Empress Elena, many arrogant words were spoken about her to our deacon Elizar Tsyplyatev.

But there are also indirect signs of dislike of subjects for the Grand Duchess. It is significant, for example, that Elena's contribution to the Trinity Monastery, made on behalf of her son, Grand Duke Ivan in 1538/39, amounted to only 30 rubles. Of course, the appropriate order on behalf of the eight-year-old boy was made by one of his then guardians. In the same row is the fact noted above of the amazing brevity of the chroniclers, who honored the memory of the deceased ruler with only a few lines (meanwhile, as we remember, a lengthy and skillfully written Tale was devoted to the death of Vasily III).

Thus, the hostility towards Elena, at least part of the court elite, is beyond doubt. If you ask the famous question of Roman jurists “qui prodest?” - who benefited from the death of the Grand Duchess in the spring of 1538, then in response you can compile a long list of relatives of the disgraced, as well as those whose parochial interests were hurt by the rise of Prince. Ivan Ovchina Obolensky. The choice of the moment for the alleged crime also speaks of the same: after the death of both specific princes in prison, the dynastic problem was removed from the agenda, and with the disappearance of the pretenders to the Moscow throne, the grand ducal boyars could no longer fear that their places at court would be occupied by the servants of one of "Princes of the Blood" On the other hand, at the beginning of 1538, Ivan IV was only seven and a half years old, which meant that the dissatisfied had to endure the ruler and her favorite for a long time, who had already managed to show their decisiveness and promiscuity in means. There are, as we see, all the conditions for the emergence of a conspiracy ...

But, of course, all these indirect considerations do not allow us to unequivocally assert that the Grand Duchess was poisoned. Historians have different attitudes to the message of Herberstein quoted above. Some prefer to cite it without comment, others consider this news to be quite trustworthy, while others, on the contrary, strongly reject it, insisting on the natural causes of the death of the ruler.

Recently, information has appeared in a number of popular science publications that seem to confirm the rumors of almost 500 years ago. It's about on the results of the pathological and anatomical examination of the remains of the Grand Duchesses from the necropolis of the Kremlin's Resurrection Monastery. According to T.D. Panova and her co-authors, the high content of arsenic and mercury found in the bones of Elena Glinskaya indicates that the ruler was indeed poisoned. Skeptics, however, are slow to agree with this conclusion. So, S. N. Bogatyrev emphasizes the inadequacy of our knowledge about the use of chemistry for medical and cosmetic purposes in Muscovy in the 16th century. Therefore, according to the scientist, relative indicators look more convincing than absolute figures. Meanwhile, the arsenic content in the remains of Elena Glinskaya is significantly lower than in the bones of a child from the family of Staritsky Prince Vladimir Andreevich, about whom it is known for certain that he was poisoned by order of the Tsar in 1569. At the same time, the poisoning did not affect the level of mercury in the body of the unfortunate victims.

Obviously, before the publication of a full scientific report on the results of the examination of the remains of Grand Duchess Elena, it would be premature to draw any final conclusions. But regardless of whether the Grand Duchess was poisoned or fell victim to some transient illness, her death dramatically changed the situation at the Moscow court. Having lost his patroness, the recent favorite lost everything: power, freedom and life itself. For those who spent the years of the reign of Elena Glinskaya in disgrace, there was a chance to re-assert themselves.

This text is an introductory piece. author12. Acquisition of the True Cross of the Lord by Elena, the mother of Constantine the Great, and the baptism of Elena-Olga, the wife of Igor-Khor Three vengeances for the death of Igor-Khor 12.1. Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, visits Jerusalem and finds the True Cross of the Lord there. It is believed that at the beginning of IV

From the book The Beginning of Horde Russia. After Christ. Trojan War. Foundation of Rome. author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich12.3. The revenge of Olga-Elena, the wife of Prince Igor, for his execution and the baptism of Olga-Elena in Tsar-Grad is a reflection crusades end of the XII - beginning of the XIII century and the acquisition of the Cross of the Lord by Elena, mother of Konstantin This is what the Romanov version says about Princess Olga-Elena, wife

From the book The Beginning of Horde Russia. After Christ. The Trojan War. Foundation of Rome. author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich12.3.2. Three revenges of Olga-Elena, Igor's wife. The first revenge of Olga-Elena V.N. Tatishchev reports the following. “Mal Prince. drevlyansky. Olga generosity. FIRST REVENGE. Ambassadors living in the earth. SECOND VENGEANCE. The ambassadors are burned. Igor's grave. THIRD REVENGE. The Drevlyans are beaten ... (notes by V.N.

author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich12. Acquisition of the True Cross of the Lord by Elena, mother of Constantine the Great and baptism of Elena = Olga, wife of Igor-Chorus Three vengeances for the death of Igor-Chorus 12.1. Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, visits Jerusalem and finds the True Cross of the Lord there. It is believed that at the beginning of IV

From the book The Foundation of Rome. Beginning of Horde Russia. After Christ. Trojan War author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich12.3. The vengeance of Olga-Elena, the wife of Prince Igor, for his execution and the baptism of Olga-Elena in Tsar-Grad is a reflection of the crusades of the late 12th - early 13th centuries and the acquisition of the Holy Cross by Elena, the mother of Konstantin

From the book History of Russia from ancient times to the beginning of the 20th century author Froyanov Igor YakovlevichThe reign of Elena Glinskaya and the boyars In December 1533, Vasily III died unexpectedly, in whose reign A.A. Zimin sees many features of future transformations of the 16th century. Under the young heir to the throne, the three-year-old Ivan, a council of trustees was created according to the will. Through

From the book Ivan the Terrible and the accession of the Romanovs author Balyazin Voldemar NikolaevichBOARD OF ELENA GLINSKAYA The beginning of the reign of Elena GlinskayaVidny modern historian R. G. Skrynnikov describes the beginning of the reign of Elena Glinskaya as follows: “A young widow, having barely celebrated the wake of her husband, made Ovchina her favorite. Later, rumor will call the favorite genuine

From the book Pre-Letopisnaya Rus. Russia pre-Orda. Russia and the Golden Horde author Fedoseev Yury GrigorievichChapter 7 Sophia and Vasily, Elena and Dmitry. The wedding to the kingdom of Dmitry Ivanovich. Basil's Rise. Ereseborsky Church Sopor. Elena's death and Dmitry's imprisonment. Continuity of reign. Elimination of the independence of the specific principalities. Autocracy of Basil III.

From the book The Split of the Empire: from the Terrible-Nero to Mikhail Romanov-Domitian. [The famous "ancient" works of Suetonius, Tacitus and Flavius, it turns out, describe Great author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich4. The murder of Agrippina is the poisoning of Elena Glinskaya According to Roman sources, Agrippina, the mother of Nero, was treacherously killed. Moreover, some laid the blame on Nero himself, who supposedly hated his mother. Here is the story of Suetonius. “He disliked his mother because

From the book Favorites of the rulers of Russia author Matyukhina Yulia AlekseevnaFavorites of Elena Glinskaya: S. Belsky, Ivan and Fyodor Ovchin Telepnev Prince Vasily III inherited from his father Ivan III the policy of resolutely gathering Russian lands. By nature, unlike his father, Vasily was rather weak-willed, soft and indecisive, but if it came to

From the book "The Dowager Kingdom" [The political crisis in Russia in the 30-40s of the 16th century] author Krom Mikhail Markovich2. From the "triumvirate" - to the sole rule of Elena Glinskaya (December 1533 - August 1534) Even M.N. Tikhomirov in his early work, comparing the news of the Pskov Chronicle about the arrest of Yuri Dmitrovsky by the Grand Duke's "clerks" with the petition of Ivan Yaganov, came to

From the book Chronology Russian history. Russia and the world author Anisimov Evgeny Viktorovich1538 Death of Empress Elena Glinskaya Vasily III's widow Elena Glinskaya became regent under the three-year-old Ivan IV. Immediately she showed herself as a domineering and ambitious ruler and disgraced the brothers Vasily III, Yuri and Andrei Ivanovich. In the summer of 1536, Yuri was killed in

From the book with fire and sword. Russia between the "Polish eagle" and the "Swedish lion". 1512-1634 author Putyatin Alexander YurievichChapter 2. CHILDHOOD YEARS OF IVAN IV. THE WAR OF ELENA GLINSKAYA. BOYAR GOVERNMENT To understand what passions flared up in the Kremlin chambers at the end of 1533 - the beginning of 1534, one will have to go back several years. The history of the second marriage of Vasily III is necessary for understanding that in

From the book Moscow. Path to empire author Toroptsev Alexander PetrovichThe state experience of Elena Glinskaya “Love of God, mercy, justice, courage of the heart, insight of the mind and a clear resemblance to the immortal wife of Igor” (N. M. Karamzin), as well as a certain similarity of the domestic political situation in Kievan Rus IX century and the country of Muscovy XVI century

Elena Vasilievna Glinskaya was not a representative of a noble family, and in Russia it was not accepted that the widow of the Grand Duke played an important role in politics. Nevertheless, she managed to take power and do many important things: make peace with Poland and confirm a lucrative agreement with Sweden, as well as carry out a monetary reform, and this is not the whole track record of her short reign.

Who is she?

Elena Vasilievna came from a family that, according to legend, traced its genealogy to Khan Mamai. After the defeat of the uncle's rebellion, Mikhail Lvovich, the Glinskys fled to Muscovy. Not a very profitable party for the Moscow prince. However, Vasily III liked Elena: soft facial features, young age, red hair (found in a burial), as well as height by the standards of that time - 165 cm - captivated Vasily.

In 1526 they got married, and a year before that, Vasily III tonsured his first wife as a nun, Solomonia Saburova. He had been married to her for 20 years, but the marriage was childless.

Rise to power

Four years after the wedding, Elena and Vasily had an heir, the future Tsar Ivan IV. Vasily III lived for another three years and died in 1533, appointing a council of trustees of nobles to rule. However, soon, not without the help of her favorite stableman Ivan Fedorovich Ovchin Telepnev-Obolensky, Elena made a coup.

The first to suffer was the brother of the late Grand Duke Vasily, Yuri Ivanovich, the appanage prince Dmitrovsky. He was accused of luring some of the Moscow boyars into his service and thought to take advantage of Ivan Vasilyevich's infancy in order to seize the throne of the Grand Duke.

Yuri was captured and imprisoned, where he was said to have starved to death. A relative of the Grand Duchess, Mikhail Glinsky, was also captured and died in prison. Other guardians were either thrown into prison or fled to Lithuania.

So Grand Duchess Elena Vasilievna became the second sovereign ruler of Russia after Princess Olga, even if she was a regent. It is probably worth mentioning also the wife of Vasily I, Sofya Vitovtovna, but her power in many lands was purely formal.

Appearance reconstruction

In power

During the reign, Elena Vasilievna prevented several plots against herself by the boyars. They did not like Lithuanians either among the people or in noble circles. Separate dissatisfaction was caused by the behavior of the lover - Ivan Telepnev-Obolensky.

Elena Glinskaya was regent under the young Ivan for five years, and during these five years she managed to win the war against the Polish king Sigismund I. In 1537, an agreement with Sweden on free trade and benevolent neutrality from 1510 was confirmed.

The Swedes pledged not to help the Livonian Order and Lithuania. Under Glinskaya, in 1535, Peter Maly Fryazin laid the Kitaigorod wall. New settlements were also founded on the border with Lithuania, Ustyug and Yaroslavl were restored.

The most important moment in the reign of Elena Glinskaya is the implementation of the monetary reform (begun in 1535). She actually introduced a single currency in the Russian state. Now all over Muscovy went silver money weighing 0.34 grams with the image of St. George. This was a significant step towards stabilizing the state's economy - before the reform, there were many counterfeit coins in circulation. After the reform, mints remained only in Moscow and Novgorod.

Under Glinskaya, a ban was introduced on the purchase of land from service people, control over the growth of monastic land ownership was intensified, and the tax and judicial immunities of the church were reduced. An important part of the innovations was the introduction of labial elders, elected from service people. Tselovalniks were elected as their assistants from among the black-haired peasants. Lip elders, for example, had the right to independently judge the robbers.

Death takes the young

A young, beautiful and intelligent regent could have brought Ivan IV to adulthood, but, alas, she died on April 4, 1538. One of the main versions about the reasons for her death is poisoning. Allegedly, the Shuiskys added poison and mercury. The examination reported an increased content of mercury in the remains. However, at that time, mercury was part of the white and many drugs, so the version of the administration is controversial.