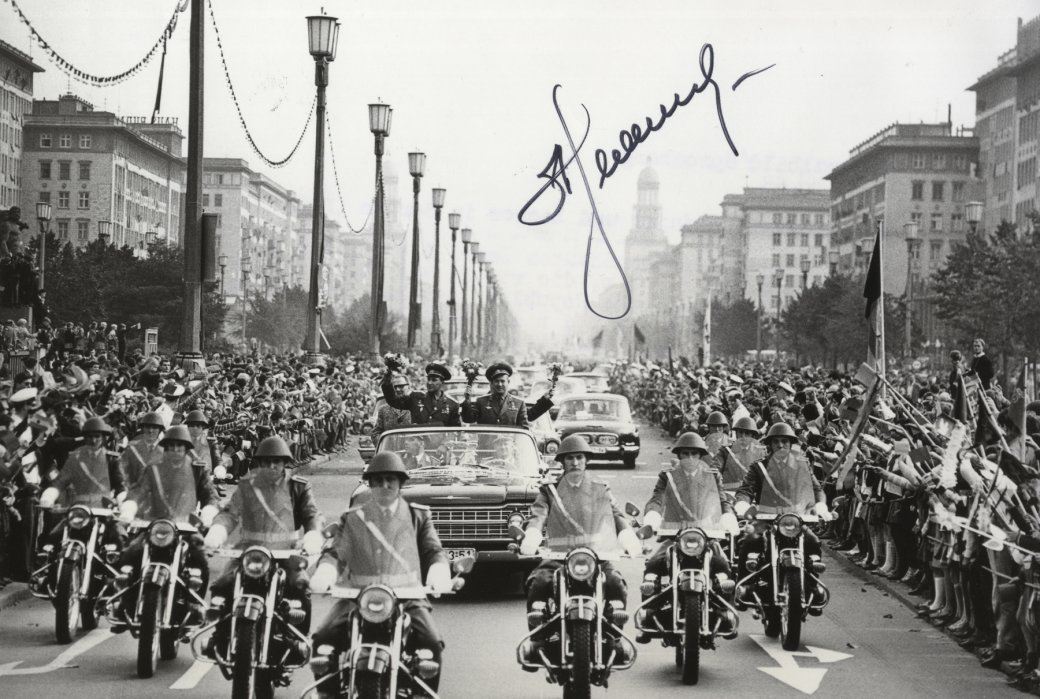

Voskhod 2 spacecraft crew. Alexey Leonov: the first in outer space. The film "Meetings on Perm land"

On March 18, 1965, the first human spacewalk took place: Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov spent 12 minutes 9 seconds in the airless space outside the Voskhod-2 spacecraft.

The EVA technology was part of the Soviet lunar mission program. This is how the astronaut had to go to the lunar module. Also in the USSR they knew that a flight with an astronaut into outer space was planned for May 1965 in the United States.

"I see, here they are - on the Christmas tree!"

It even saves on costumes. - To be honest, the ship "Voshod-2", which they flew, was primitive. In fact, only Yury Gagarin's East was transformed. It is still hard to believe that such a wonderful thing was done in the wreckage, says Zverzhleisky.

Two years later, Leonov receives another historic task - he is part of a group of cosmonauts ready to fly to the moon. Saying the famous phrase: "For a man this is one small step, for mankind a huge leap." Presumably, Leonov is very upset by his defeat. He estimated that he had directly threatened him with death seven times in his course.

Alexey Arkhipovich Leonov was born on May 30, 1934 in the village of Listvyanka in Kemerovo region. Later he became a fighter pilot and got into the first detachment of astronauts.

Leonov paid special attention to his physical training.

Every day I ran at least 5 kilometers and swam 700 meters.

Pavel Ivanovich Belyaev was born on June 26, 1925 in the village of Chelishchevo Vologda region. In 1960 he was enlisted in the cosmonaut corps.

However, he had previously done this in an overnight interview with a young Polish pilot. In March, Star City, as this secret center is called, hears that the Polish flight is in question. Everyone suffers from bad mood. Alcohol is forbidden on the table to restore them. And with him the standard of sincerity. Leonov reassures Germashevsky, convinces him that he cannot give up. They talk all night. He told me about the unknown details of his mission. That he almost cost her her life.

Germashevsky, who flew into space three months later. Today, Leonov is still friends. I remember him not only as good man, but also as a good educator who calmed our fatigue and stress. His observations were confirmed by the Polish director Adam Ustinovich, who met the general. Most remembered his wide smile, he says.

Many believed that at 40, Pavel Belyaev was already too old for such a task. But since increased emotional stress was expected during its implementation, the psychological stability of the crew acquired special importance.

This is how Leonov recalls Belyaev.

Leonov is also a person about the soul of an artist. Over the years, to relieve stress, he began painting. The only motive for his work is space and spaceships. Many art collectors appreciate his work. On the contrary, the communist authorities, up to the age, looked at their picture with distrust. In a naturalistic way, he showed the Soviet spaceship, and yet their depictions were often clandestine. He was not afraid to make pitiful looks, as if a heap of iron was about to fall apart.

Some of his paintings were confiscated by the censors. Four years ago, thieves broke into his villa, taking his memorial uniform and all the medals he received for space exploration. He recently gave an interview to a French journalist. He did not hide his regret: Before, when we returned from the expedition, we were waiting for the red carpet. Sorry, nothing will help here.

Pavel is a melancholic, and I am a sanguine. I pushed him and he held me back. During one of the parachute jumps, Pavel received a screw fracture of both leg bones. They brought him to the hospital. The radiologist was confused and, twisting the lens of the apparatus, dropped it directly on the crushed bones. "Can you be a little more careful?" Pasha said, gritting his teeth. And that's all. He was a man of great endurance.

Only a year after this fracture, Belyaev achieved a return to full-fledged training.

The Voskhod-2 spacecraft launched on March 18, 1965 at 10:00 Moscow time with Lieutenant Colonel Pavel Belyaev and Major Alexei Leonov on board. In order to accommodate a crew of several people, ejection seats had to be abandoned on Voskhod-type ships, which made it impossible to rescue astronauts in the first 40 seconds of flight in the event of a launch vehicle failure. The risk was so great that after two manned launches, ships of this type were no longer used.

Leonov recalled that after the completion of the flight, Korolev admitted:

When I let you go, stayed on the launch pad, I was scared. I thought, “What have I done? He sent his sons!”

The launch was successful, but as a result of a calculation error, the orbit into which Voskhod-2 was launched turned out to be higher than planned. This mistake allowed the crew to set the official world record for human flight altitude (497.7 km), but if the brake engine failed, the astronauts had no chance to survive.

Both cosmonauts were dressed in soft Berkut spacesuits. Leonov later said that in a conversation with him after landing, Belyaev admitted that he would not have returned to Earth alone.

The mass of the Berkut suit is 20 kg, the mass of the satchel with an autonomous life support system is 21.5 kg. The supply of oxygen in the cylinders of the backpack was enough for 45 minutes. A backup oxygen supply system was mounted in the lock chamber and connected to the suit with a hose. When connected inside the ship, the spacesuit was provided for 4 hours.

The spacewalk began 1 hour 35 minutes after liftoff, when the spacecraft was flying over Egypt. In open space, Leonov found himself over the Black Sea. At that moment, Belyaev reported by radio:

Attention! The man went into outer space!

Many times Leonov noted that he was struck by the silence in which he clearly heard the beating of his own heart.

The picture of the cosmic abyss that I saw, with its grandeur, immensity, brightness of colors and sharp contrasts of pure darkness with the dazzling radiance of the stars, simply struck and fascinated me. To complete the picture, imagine - against this background, I see our Soviet ship, illuminated by the bright light of the sun's rays. When I was leaving the gateway, I felt a powerful stream of light and heat, reminiscent of electric welding. Above me was a black sky and bright, unblinking stars. The sun seemed to me like a red-hot fiery disk.

The connection worked steadily. Leonov heard the TASS message announcing his feat to the world, and even spoke with Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, who was in the Kremlin.

Leonov successfully filmed with the S-97 movie camera, but he could not use the Ajax portable camera provided by the KGB. The shutter was actuated by a cable, but due to the deformation of the suit, it was not possible to use it.

Under ground conditions, the suit was tested in a pressure chamber up to a pressure corresponding to an altitude of 60 km. In space (under conditions of deep vacuum), the internal pressure inflated the suit much more than expected. The provided gap between the shoulders of the suit and the edges of the hatch was two centimeters. During the flight over Yakutia, the cosmonaut tried to return to the airlock, but he failed.

Leonov recalls:

AT space vacuum the suit was swollen, neither the stiffening ribs nor the dense fabric could withstand it. My hands came out of my gloves when I grabbed the handrail, and my feet came out of my boots. In this state, of course, I could not squeeze into the airlock hatch.

Then the astronaut released the pressure inside the spacesuit to the emergency mode.

During the passage of the commission, we climbed to a height of 14 thousand meters with an oxygen mask, and before that we breathed pure oxygen so that nitrogen was washed out. One hour was enough for some, and not for others. My comrade's nitrogen boiled before my eyes: his hands swelled up, his eyes sunk in. I knew that the same thing could happen to me, but I took a chance.

And Leonov managed to squeeze into the lock chamber, but not with his feet forward, as it should be according to the instructions, but with his head. However, the cosmonaut could not hit the descent vehicle head first in the correct position. Due to physical activity, the body temperature rose to 38 degrees, the pulse jumped to 162, and the respiratory rate to 31 per minute. Sweat so flooded his face that Leonov opened the visor of the pressure helmet, barely hitting the ship, without waiting for the inner hatch to close.

Leonov managed to explain his actions to the commission during the debriefing:

The situation happened unexpectedly. My connection was open. Imagine, I would say: "I can not enter the ship." You would immediately start collecting commission. You are legally required to elect a chairman. You would then start asking me why and how. Time runs. Then they would have gone to confer what to do, and I would have died already.

In the atmosphere of the ship, the oxygen content suddenly began to increase (up to 45% instead of 20%). Any spark in the electrical system could cause an explosion. The crew lowered the humidity and air temperature to 10°C, but nothing more could be done, and in the end the astronauts even fell asleep from oxygen poisoning. They panicked on Earth: there might not be enough air for breathing before landing, which could be carried out on the territory of the USSR only after the 16th orbit. And again the astronauts were lucky: after 7 hours, the supply of excess oxygen suddenly stopped, and everything went back to normal.

The next problem during this flight was related to the failure of the attitude control system. After shooting off the airlock, the ship began to rotate, a lot of dust and debris arose. Automation did not build the orientation necessary to turn on the brake installation. From the Earth, they were forced to allow for the first time in the history of astronautics to land in manual mode.

Due to the structure of the ship, "aiming" while sitting in a chair was impossible. Belyaev was forced to unfasten himself and, held by Leonov, built a pre-landing orientation. Belyaev managed to get to his seat in 22 seconds, but this delay caused a flight of 165 km. As a result, the descent vehicle landed in the taiga, 75 km from the city of Berezniki in the Perm Region.

Guy Severin, Head of Design Bureau "Zvezda":

There was no news from them. Korolev, Keldysh, and I sat and waited. To be honest, we thought the crew was dead. And when the message came that they had landed in the taiga, alive and well, Sergei Pavlovich began to cry.

The ship landed on March 19 at 12:02:17 p.m. The first attempt to open the hatch failed due to close tree trunks and deep snow. There was no connection. The astronauts lit a fire. The frost increased to minus 20 degrees by night.

My suit was knee-deep in moisture, about 6 liters. So in the legs and bubbling. Then, already at night, I say to Pasha: "Well, that's it, I'm cold." We took off our suits, stripped naked, wrung out our underwear, put it back on. Then they ripped open the screen-vacuum thermal insulation of the cabin skin. They threw away all the hard part, and put the rest on themselves. These are nine layers of aluminized foil, covered with dederon on top. Parachute lines were wrapped around the top like two sausages.

By dawn on March 20, the Voskhod-2 landing site had been established. Helicopters arrived, but could not land due to tall trees. Rescuers traveled on skis. Helicopters dropped warm clothes and food. A huge cauldron was even delivered, in which water was heated so that the astronauts could swim in it and warm themselves. Rescuers built a log cabin-hut, in which they organized two sleeping places.

Thus another night passed. The next day, March 21, Leonov and Belyaev, together with rescuers on skis, reached the helipad cleared by lumberjacks, from where they were taken to Perm, then to Baikonur and from there to Moscow, where their solemn meeting was organized.

The excitement of this flight affected the health of Pavel Belyaev, and after 5 years he died from an exacerbation of peptic ulcer. Alexei Leonov continued his career as an astronaut, made another space flight in 1975 under the Soviet-American Soyuz-Apollo program and escaped death at least twice more.

In 1969, junior lieutenant Viktor Ilyin, who was preparing an assassination attempt on Brezhnev, shot at the car where Leonov was. The bullet pierced the cosmonaut's overcoat, but did not hit him himself. In 1971, Leonov was supposed to launch into space on the Soyuz-11, but two days before the launch, one of his crew members fell ill. Doubles flew and died from depressurization upon landing.

According to the schedule of the Soviet lunar program, Alexei Leonov in September 1968 could become the first man on the moon. However, these plans did not come true. Neil Armstrong was the first American to walk on the moon in 1969.

The Voskhod-2 flight was the last manned flight during the lifetime of Sergei Pavlovich Korolev. He died on the operating table. The heart couldn't take it.

The new Russian feature film "Time of the First" tells about those events, which is released on April 6, 2017.

When the descent passed, they reported that they had landed and were detected by air defense and tracking stations ... The report came from the crew: they are on Earth, everything is in order. Naturally, we calmed down, and we were given permission to go on vacation.

And when we had already arrived home, after 2-3 hours the duty officer appeared in a car and ordered me to immediately report to S.P. Korolev. Vadim Volkov, a future cosmonaut, was with me, and we went to the joint venture.

On the way, we learned that the joint venture was very worried, since there was no exact command about the condition of the astronauts and measures for their evacuation. He was forced to appoint his own group in order to have accurate data on the spot on the progress of the evacuation and provide the necessary assistance in the evacuation of the ship and crew.

I was promoted to head of the group; V. Volkov, V. Shapovalov, S. Artemyev were with me. I was given a representative of the plant, Yu.I. Lygin. At 9 o'clock in the evening we received a command to fly from Baikonur to Perm at 12 o'clock at night, where we arrived at 5 o'clock in the morning. A helicopter was waiting there, which took us 5 km from the landing site. We started clearing up the situation.

The forest in this place was very dense, the earth was not visible at all, the parachute canopy hung on the trees. There is communication with the astronauts by radio, but no one saw them, they only knew that the smoke of the fire was rising from there and they reported by code that everything was fine with them. We knew that the astronauts had limited resources for warmth, and their clothes did not save them for a long time. Weather conditions were favorable, only -5°C. Snow about 1.5 m and trees 40 m high did not allow the search group to land troops there, since this was prohibited by the instructions.

We turned to the pilots of the Air Force helicopters who were there, they refused us: until there is a command from the Central Command Post, they will not be able to do anything. We approached the polar aviation pilot - his Mi-1 was standing to the side - I don’t remember his last name, but A. Leonov knows him - and asked to be dropped off there. At least on the "Christmas tree" (cable ladder. - Auth.) Drop off, so that we go down it and get to them. The pilot said that he also had no right:

- Only two people can give a command - Kuvshinov [one of the leaders of the Civil Air Fleet] and Anokhin [honored test pilot of the USSR, trained the first group of cosmonauts].

- I'm from Anokhin.

- What's his name?

- Sergei Nikolaevich.

- Sit down.

The three of us sat down - Artemiev, Volkov and I, not making out for the noise of the engine, so that one would be dropped off - the Mi-1 does not take more than two people. Loaded skis, axes, saws and flew. On the way, seeing that there were three of us, the pilot said that he would not be able to hover, but would land us two kilometers from the astronauts. Next you need to go skiing. He hovered over a birch grove; the height of the trees is 20 meters. He threw away the rope ladder and told us to go down. We dropped the load and all three went down.

Unpleasant were the sensations when jumping down the stairs. He showed us the direction and flew away. We put a compass in this direction and wanted to move. But it turned out that the ski bindings fit well with my boots, and Volkov and Artemiev were in fur boots, and therefore there were difficulties with their bindings. After walking 100 meters, I was forced to give the command to return and prepare a place for a helicopter landing, and I myself moved to the desired place alone.

After a while, I heard shots and continued to follow them. At 9:00 we landed, and I came to them at 2:00 in the afternoon. Walking 2 km for five hours, having the first category in skiing, is a shame, of course ... but very difficult: loose snow 1.5 m deep.

When I felt the smoke, saw the ship, my strength somehow increased. I drove up. Belyaev was sitting on the ship and spoke in an expressive language with the plane that was patrolling over them. I went. He looked at me so indifferently at first. I grabbed his leg. He touched me, and then rushed to hug. He later said that he thought he was hallucinating. "How it is? Followed us and ended up here. Did you come here before us?"

Leonov was aside by the fire. He heard voices, rushed to us. There they had a path made, and the fire itself was on the ground. The snow melted and how they were in a well. Rejoiced, began to question. I took the walkie-talkie from P. Belyaev and reported to the Joint Venture: "Belyaev has arrived, everything is in order, we are taking measures for evacuation." After that, he said through the plane that, first of all, the crew needed warm clothes, sleeping bags, tents and food. Soon the helicopter dropped us 8 "seats". We only found two. But, fortunately, there were sleeping bags and tents. And they began to prepare a place to rest. The astronauts were exhausted. For them, this was the second night without sleep. Leonov began to joke.

... I was very thirsty - I spent a lot of energy on the road. I sucked on the tank of water and drank almost everything they had left. “You see, we have nothing to eat, and you took away the water.” They ate all the food, and adapted a container from NAZ to get water. The second approach from the helicopter dropped products: pasta, crackers. I managed to tell them to make hot food. And the next day they threw out a 40-liter tank of tea and began to deliver hot food.

By the end of the day, a group arrived, which was intended for evacuation from the Air Force. Doctor Tumanov came. Another fire was lit. Tumanov had meat broth tablets. We boiled them, and one should have seen with what pleasure Belyaev and Leonov volley drank the hot broth. For example, I could not touch this mug.

The doctor examined them, listened. Leonov immediately turned: "Can't we get warm?" Tumanov said that as an exception, of course, he poured them half a glass. They drank with pleasure, and we put them to bed. Leonov, on this metal flask, drew Tumanov the landing site along with the ship and wrote his wishes.

The next day, as soon as they woke up, evacuation measures began to be taken ... They requested a helicopter that flew to the place where we jumped. They cleared the site and sent us skis. They collected all the materials that the astronauts were supposed to take with them, gave them an escort from the search group, and sent them along the ski track to the helicopter landing site. From there they flew to Perm.

(Belyaev V. S., member of the search group)

Cosmonauts P.I. Belyaev (on the left in earflaps) and A.A. Leonov (on the right in a helmet) and the rescue expedition: engineer-colonel V.S. Belyaev (in the middle) and V.N. Volkov (on the right above him).