Vedas and fairy tales. Viktor Dragunsky - Deniska's stories (collection) Ivan Petrovich Sakharov biography

Ivan Petrovich Sakharov(August 29 (September 10), Tula - August 24 (September 5), Zarechye estate, Valdai district, Novgorod province) - Russian ethnographer-folklorist, archaeologist and paleographer.

Sakharov spent the end of his life in the small estate of Zarechye, Ryutinskaya volost, Valdai district. Died August 24 (September 5). I. P. Sakharov was buried in the cemetery near the Assumption Church in the village of Ryutina (now the Bologovsky district of the Tver region).

Write a review on the article "Sakharov, Ivan Petrovich"

Notes

Literature

- // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - St. Petersburg. , 1890-1907.

- Pypin A.N.: Forgeries of Makarov, Sakharov and others. St. Petersburg, 1898.

- Kozlov V.P. Secrets of falsification: Analysis of forgeries of historical sources of the XVIII-XIX centuries. Ch. XIII. 2nd ed. Moscow: Aspect Press, 1996.

- Toporkov A.L.// UFO. - 2010. - No. 103.

An excerpt characterizing Sakharov, Ivan Petrovich

Each person lives for himself, enjoys freedom to achieve his personal goals and feels with his whole being that he can now do or not do such and such an action; but as soon as he does it, so this action, committed at a certain moment in time, becomes irrevocable and becomes the property of history, in which it has not a free, but a predetermined significance.There are two aspects of life in every person: personal life, which is all the more free, the more abstract its interests, and spontaneous, swarm life, where a person inevitably fulfills the laws prescribed to him.

A person consciously lives for himself, but serves as an unconscious tool for achieving historical, universal goals. A perfect deed is irrevocable, and its action, coinciding in time with millions of actions of other people, acquires historical significance. The higher a person stands on the social ladder, the more he is connected with great people, the more power he has over other people, the more obvious is the predestination and inevitability of his every action.

"The heart of the king is in the hand of God."

The king is a slave of history.

History, that is, the unconscious, general, swarming life of mankind, uses every minute of the life of kings as a tool for its own purposes.

Napoleon, despite the fact that more than ever, now, in 1812, it seemed to him that it depended on him verser or not verser le sang de ses peuples [to shed or not to shed the blood of his peoples] (as in the last letter he wrote to him Alexander), was never more than now subject to those inevitable laws that compelled him (acting in relation to himself, as it seemed to him, according to his own arbitrariness) to do for the common cause, for the sake of history, what had to be done.

The people of the West moved to the East in order to kill each other. And according to the law of the coincidence of causes, thousands of petty reasons for this movement and for the war coincided with this event: reproaches for non-observance of the continental system, and the Duke of Oldenburg, and the movement of troops to Prussia, undertaken (as it seemed to Napoleon) only to to achieve an armed peace, and the love and habit of the French emperor for war, which coincided with the disposition of his people, the fascination with the grandiosity of preparations, and the costs of preparation, and the need to acquire such benefits that would pay for these costs, and stupefied honors in Dresden, and diplomatic negotiations, which, in the opinion of contemporaries, were led with a sincere desire to achieve peace and which only hurt the vanity of both sides, and millions and millions of other reasons that were faked as an event that was about to happen, coincided with it.

When an apple is ripe and falls, why does it fall? Is it because it gravitates towards the earth, because the rod dries up, because it dries up in the sun, because it becomes heavier, because the wind shakes it, because the boy standing below wants to eat it?

Nothing is the reason. All this is only a coincidence of the conditions under which every vital, organic, spontaneous event takes place. And the botanist who finds that the apple falls down because the cellulose decomposes and the like will be just as right and just as wrong as that child standing below who says that the apple fell down because he wanted to eat. him and that he prayed for it. Just as right and wrong will be the one who says that Napoleon went to Moscow because he wanted it, and because he died because Alexander wanted him to die: how right and wrong will he who says that he collapsed into a million pounds the dug-out mountain fell because the last worker struck under it for the last time with a pick. In historical events, the so-called great men are labels that give names to the event, which, like labels, have the least connection with the event itself.

Each of their actions, which seems to them arbitrary for themselves, is in the historical sense involuntary, but is in connection with the entire course of history and is determined eternally.

On May 29, Napoleon left Dresden, where he stayed for three weeks, surrounded by a court made up of princes, dukes, kings, and even one emperor. Before leaving, Napoleon treated the princes, kings and the emperor who deserved it, scolded the kings and princes with whom he was not completely pleased, presented his own, that is, pearls and diamonds taken from other kings, to the Empress of Austria and, tenderly embracing the Empress Marie Louise, as his historian says, he left her with a bitter separation, which she - this Marie Louise, who was considered his wife, despite the fact that another wife remained in Paris - seemed unable to endure. Despite the fact that diplomats still firmly believed in the possibility of peace and worked diligently towards this goal, despite the fact that Emperor Napoleon himself wrote a letter to Emperor Alexander, calling him Monsieur mon frere [Sovereign brother] and sincerely assuring that he did not want war and that he would always love and respect him - he rode to the army and gave new orders at each station, aimed at hastening the movement of the army from west to east. He rode in a road carriage drawn by a six, surrounded by pages, adjutants and an escort, along the road to Posen, Thorn, Danzig and Koenigsberg. In each of these cities, thousands of people greeted him with awe and delight.

An outstanding cultural figure of the Don at the end of the 19th - beginning of the 20th century, Khariton Ivanovich Popov was not only the founder of the Don Museum, but also the organizer of historical science on the Don and research on the history of the Don Cossacks. This is evidenced by a set of documents of personal origin, concentrated in fund 55 of the State Archives of the Rostov Region (Kh. I. Popov fund). Some of these documents refer to one of the most prominent Don historians of the beginning of the last century, Pavel Petrovich Sakharov, whose works on the early history of the Don Cossacks aroused great interest in the Don.

One of the most important aspects of his work was the preparation of a large comprehensive work on the history of the Don, a kind of metanarrative within the history of the region, which claimed exceptional cultural and historical significance on the scale of Russia and the adjacent territories of Southeast Europe and the Middle East. Such a task was set by the authorities of the Region of the Don Army. So, in 1908, during the tenure of the military ataman, Lieutenant-General A.V. Samsonov, the military authorities turned to the historian V.O. Klyuchevsky with a request to write the history of the Don. In a response letter to the ataman dated June 17, 1908, V. O. Klyuchevsky called the "lack of a well-processed history" of the Don Cossacks "an unfortunate gap in Russian historiography." Referring, however, to employment, the historian wrote that he could not take on this difficult work. But at the same time, he advised "to start the business by disassembling and bringing materials on the history of the Army, extracted both from local and from the capital's archives."

Thus, the outstanding source historian V. O. Klyuchevsky emphasized the need for the most thorough search and archeographic work as a prerequisite for creating a large study on the history of the Don. Soon after that, on October 12, 1908, the Commission for collecting materials for compiling the history of the Don Army received a statement from the students of history of Kharkov University P. P. Sakharov and V. S. Popov. They offered their services in collecting sources related to the history of the Don. In the statement, the students indicated: “We ... have some preparation for classes on Don history, such as: acquaintance with printed manuals on the history of the Don Cossacks, with published sources and with many handwritten ones, not to mention ... about the sources of general Russian history, in collections which interspersed with many information about the past of the Don Cossacks ... ". The commission chaired by A. A. Kirillov, which included I. T. Semenov, Kh. I. Popov, I. V. Timoshchenkov, Z. I. Shchelkunov and I. M. Dobrynin, decided to accept the help of students.

Several letters from P. P. Sakharov to Kh. I. Popov have been preserved. Correspondence with a venerable senior colleague, founder and head of the Don Museum and State Councilor, allows us to better understand the personality and character traits of the author of the letters. P. P. Sakharov informed Kh. I. Popov about the progress of his work on making copies of documents, shared his impressions about the most interesting, in his opinion, finds. Sometimes he asked for help in arranging access to individual archives. In a letter dated July 14, 1909, he wrote about the desirability of penetrating “... into the holy of holies of the State Main Archive in St. Petersburg - one would desperately need to look at dozens of folios of the Cabinet Affairs of Peter the Great - there is Bulavinism, and along the way, colonization, economy and life - letters of Dolgoruky the pacifier. Access to the archive is very difficult, but Taube, with his connections and desire, can arrange it. The letter testifies to the ability of P. P. Sakharov to organize the search work of several Don students with whom he worked in the archives. It also testifies to the breadth of his historical views, the desire to cover not only the event history, but also different aspects of the life and life of the Cossacks. In the same letter, P. P. Sakharov reported that he had found three cases with a mention of the participation of the Don Cossacks in the Battle of Poltava. In one of the cases, he wrote to Kh. Thus, he drew attention to the possible relationship of this ataman with the famous S. Kochet, who in 1705 was the ataman of the Don winter village.

He also pointed out that the case of 1632, which dealt with the refusal of the Don Army from the oath to Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich and which aroused great interest among historians, could have an unconventional consideration. This case, wrote P. P. Sakharov, "establishes family life on the Don that way for the Time of Troubles." The letter testifies to P. P. Sakharov's deep knowledge of the problems of Don history.

Persistently and at the same time delicately, P. P. Sakharov resolved a very difficult financial issue with Kh. I. Popov. As the de facto leader of a team of copyist students, he found serious arguments in favor of the need to increase his wages. This was especially true of work in the archives of the Ministry of Justice, where reading documents was hampered by "rottenness, nebula and nasty handwriting" and where, in addition to him, only V. S. Popov could work "with his skill and already great information on the history of the region" .

As a persistent and hardworking student, P. P. Sakharov became known to the leaders of the Moscow archives. Therefore, when he turned to the manager of the Moscow archive of the Ministry of Justice, D. Ya. Samokvasov, with a request for admission to work in the archive of one of the copyists hired by him, the well-known archivist went to meet the student.

P. P. Sakharov shared with Kh. I. Popov the plans of his scientific work. In a letter dated June 14, 1909, he asked about the possibility of publishing his work on the history of colonization and life of the Don Cossacks. He proposed to publish the first part of the work, which included "The 16th century, the Troubles and about Azov", or a story about the events of 1637-1641, when the Don Army took Azov and held it in their hands.

Archival searches, which P. P. Sakharov reported in his letters of 1909 to Kh. materials." This work received a gold medal from Kharkov University, and its manuscript is kept in the Rostov Regional Museum of Local Lore. On the basis of this work, in different issues of the Don Regional Gazette, a publication was made entitled “On the Question of the Origin of the Don Cossacks and the First Feats of the Don Cossacks in Defense of the Homeland and Faith in the Service of the First Russian Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich the Terrible.” Somewhat later, in 1914, in the Notes of the Rostov-on-Don Society of History, Antiquities and Nature, his work The Origin of the Don Cossacks was published.

A comprehensive and in-depth analysis of the situation on the Don on the eve of the elections to the 4th State Duma, carried out in an extremely detailed study by B. S. Kornienko, allowed the latter to conclude that there was an ideological closeness between P. P. Sakharov and Kh. I. Popov. Both of them, in his opinion, represented the so-called "Right Don", which stood on the positions of Russian nationalism, and P. P. Sakharov brought a historical basis for these ideas. As B. S. Kornienko noted, the “nationalism” of P. P. Sakharov and Kh. I. Popov differed from another direction of nationalism on the Don, the so-called “Cossack” nationalism. The positions of the latter were supported by the ideologists of Cossack isolation and independence, the Don journalist S.A. Kholmsky and the publicist-historian E.P. Savelyev. And if P. P. Sakharov and Kh. I. Popov emphasized the closest connection between Russia and the Don over the centuries of Cossack history, then S. A. Kholmsky and E. P. Savelyev were their ideological opponents and emphasized the historical conditionality and the need for independence Don. This generally correct position, expressed by B. S. Kornienko, can be supplemented by the fact that, in terms of his ideological positions, P. P. Sakharov turned out to be close not only to Russian nationalism, but also to liberal populism, which was manifested in the formation of the concept of labor origin of the Don Cossacks in the 16th century at the expense of immigrants from Russian lands with the inclusion of a Turkic element in it.

Letters to Kh. I. Popov in 1909 from the fund 55 of the GARO reflect the initial stage of the formation of P. P. Sakharov as a knowledgeable and interested researcher of the history of the Don. The life path of P. P. Sakharov developed, however, in such a way that he did not have a chance to publish his works during the Soviet period. In 1957, he wrote an interesting manuscript on the historiography of the question of the origin of the Don Cossacks. It has not been published so far and is stored in the Rostov Regional Museum of Local Lore. Another of his manuscripts is also stored there, dedicated to the campaign of the Cossacks of ataman Ermak to Siberia. In the life of P. P. Sakharov there were links to Central Asia for service in the Volunteer Army in 1919, a long stay in Maykop, where he was hiding from the authorities, and a return to Rostov-on-Don during the Khrushchev thaw. At that time, at the end of his life, Rostov historians and local historians met with him, including A.P. Pronshtein and B.V. Chebotarev, who knew him well. The actualization of the problems of the early history of the Don Cossacks at the turn of the past and present centuries caused an increase in interest in the life and work of P. P. Sakharov, an original researcher of the Don past.

NOTES

1. GARO. F. 55. Op. 1. D. 622.

2. Lieutenant General Baron F. F. von Taube - military ataman in 1909-1911.

3. Kornienko B. S. Right Don: Cossacks and the ideology of nationalism (1909-1914). SPb. : Publishing House of Europe. un-ta, 2013.

4. About the life and creative path of P. P. Sakharov, see: Mininkov N. A. Pavel Petrovich Sakharov - historian of the Don Cossacks // Cossack collection. No. 3. Rostov n / D, 2002. S. 216-320.

5. For this article, see: Markedonov S.M. Failed controversy: (unpublished manuscript by P.P. Sakharov as a source on the history of Don. Historical science of the XX century): materials and abstracts. Orenburg, 2000, pp. 103-107; Mininkov N. A. Unknown page of the historiography of Yermak's campaign: Rostov rukop. // Social thought and traditions of Russian spiritual culture in historical and literary monuments of the XVI-XX centuries. Novosibirsk, 2005, pp. 56-66.

P. P. SAKHAROV'S PUBLICATIONS IN THE DON ELECTRONIC LIBRARY

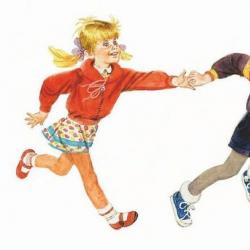

The famous "Deniskin stories" by Viktor Yuzefovich Dragunsky have been loved by readers for more than half a century. The stories of Deniska Korablev are included in the school literature curriculum, they are published and republished with the same success.

Our book is special. The illustrations for it were made by Veniamin Nikolaevich Losin, an outstanding domestic illustrator of children's books, who drew "Deniska's stories" many times. For the first time, our book contains the best versions of illustrations by V. Losin, published in various publications.

For elementary school age.

Viktor Yuzefovich Dragunsky

Deniskin's stories

About my dad

When I was little, I had a dad. Viktor Dragunsky. Famous children's writer. Only no one believed me that he was my dad. And I screamed: "This is my dad, dad, dad!" And she started to fight. Everyone thought he was my grandfather. Because he was no longer very young. I am a late child. Junior. I have two older brothers - Lenya and Denis. They are smart, scholarly, and quite bald. But they know a lot more stories about dad than I do. But since it wasn’t them who became children’s writers, but I, then they usually ask me to write something about dad.

My dad was born a long time ago. In 2013, on the first of December, he would have turned one hundred years old. And not somewhere there he was born, but in New York. This is how it happened - his mom and dad were very young, got married and left the Belarusian city of Gomel for America, for happiness and wealth. I don’t know about happiness, but they didn’t work out with wealth at all. They ate exclusively bananas, and in the house where they lived, hefty rats ran. And they returned back to Gomel, and after a while they moved to Moscow, to Pokrovka. There my dad did not study well at school, but he liked to read books. Then he worked at a factory, studied acting and worked at the Satire Theater, and also as a clown in a circus and wore a red wig. Maybe that's why I have red hair. And as a child, I also wanted to be a clown.

Dear readers!!! People often ask me how my dad is doing, and they ask me to ask him to write something else - bigger and funnier. I don’t want to upset you, but my dad died a long time ago when I was only six years old, that is, more than thirty years ago, it turns out. Therefore, I remember very few cases about him.

One such case. My dad was very fond of dogs. He always dreamed of getting a dog, only his mother did not allow him, but finally, when I was five and a half years old, a spaniel puppy named Toto appeared in our house. So wonderful. Eared, spotted and with thick paws. He had to be fed six times a day, like a baby, which made mom a little angry ... And then one day dad and I come from somewhere or just sit at home alone, and we want to eat something. We go to the kitchen and find a saucepan with semolina, and so tasty (I generally can’t stand semolina) that we immediately eat it. And then it turns out that this is Totoshina porridge, which my mother specially cooked in advance to mix it with some vitamins, as it should be for puppies. Mom was offended, of course. Outrageous is a children's writer, an adult, and has eaten puppy porridge.

They say that in his youth my dad was terribly cheerful, he was always inventing something, around him there were always the coolest and witty people in Moscow, and at home we always had noisy, fun, laughter, a holiday, a feast and solid celebrities. Unfortunately, I don’t remember this anymore - when I was born and grew up a little, dad was very ill with hypertension, high blood pressure, and it was impossible to make noise in the house. My friends, who are now quite adult aunts, still remember that I had to walk on tiptoe so as not to disturb my dad. Somehow they didn’t even let me in to see him very much, so that I wouldn’t disturb him. But I still penetrated to him, and we played - I was a frog, and dad was a respected and kind lion.

My dad and I also went to eat bagels on Chekhov Street, there was such a bakery with bagels and a milkshake. We were also in the circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, we were sitting very close, and when the clown Yuri Nikulin saw my dad (and they worked together in the circus before the war), he was very happy, took a microphone from the ringmaster and sang "Song about hares" especially for us .

My dad also collected bells, we have a whole collection at home, and now I continue to replenish it.

If you read "Deniska's Stories" attentively, you will understand how sad they are. Not all, of course, but some - just very much. I won't name now which ones. You yourself read and feel. And then - let's check. Here some are surprised, they say, how did an adult manage to penetrate into the soul of a child, speak on his behalf, just as if the child himself had told it? .. And it’s very simple - dad remained a little boy all his life. Exactly! A person does not have time to grow up at all - life is too short. A person only has time to learn how to eat without getting dirty, walk without falling, do something there, smoke, lie, shoot from a machine gun, or vice versa - treat, teach ... All people are children. Well, at least almost everything. Only they don't know about it.

I don't remember much about my dad. But I can compose all sorts of stories - funny, strange and sad. I have this from him.

And my son Tema is very similar to my dad. Well, spilled! In the house in Karetny Ryad, where we live in Moscow, there are elderly pop artists who remember my dad when he was young. And they call Theme just that - "Dragoon offspring." And we, along with Tema, love dogs. We have a lot of dogs at the dacha, and those that are not ours just come to us for lunch. Once a striped dog came, we treated her to a cake, and she liked it so much that she ate and barked with joy with her mouth full.

The inhabitants of villages and villages looked with surprise at the modest young man, who diligently wrote down the dreary songs of the destitute villagers, ancient legends, wedding, comic choruses of peasant round dances and gatherings. Thus, in the mid-20s of the last century, one of the leading representatives of Russian folklore studies, local historian, began his selfless activity. SAKHAROV Ivan Petrovich.

Was born SAKHAROV Ivan Petrovich he is in the family of a Tula church minister. Having lost his father early, he knew the sorrows and hardships of working life. The mother managed to attach her son to the seminary. Within its walls, an inquisitive listener developed an all-consuming interest in history. I read a lot. He carefully studied, made extracts from the "History of the Russian State" by N. M. Karamzin. The future scientist vividly reflected the first timid steps in a new field in his memoirs. Then a deep thought came to him in the middle of reading: "What is Tula and how did our fathers live?" Studying ancient folios, I came to the conclusion that it is better to study antiquities from available monuments in archives, and not just from books. Realizing this, I decided to write "Tula history". But access to the archives was closed to a poor teenager of non-noble origin. It was difficult for a man without connections and means to break into the isolated circle of the landowner-bureaucratic aristocracy.

There was no public library in the provincial center. Few were interested in science, literature, contributed to enlightenment. Thanks to the petition of progressive persons, primarily the educated inspector of the cadet corps, historian I.F. Afremov, it was possible to obtain official permission to visit the archives of the provincial and weapons boards, the noble deputy assembly, churches, and monasteries. Here SAKHAROV Ivan Petrovich revealed dozens of letters, lists from scribe books, the Tula bit book and other acts.

The patrons decided to donate his first creation, Fragments from the History of Tula, to the little-known Moscow magazine Galatea. A piece of the past, dedicated to the siege in the Tula Kremlin by the tsarist troops of the rebels under the leadership of I. Bolotnikov, saw the light in May 1830. The advanced public of the city gladly welcomed the initiative of a capable researcher. However, the diocesan authorities, headed by the bishop, condemned the "boy" who took it into his head to speak in the press on secular topics. Only the intercession of Afremov, the teachers of the gymnasium, saved the seminarian from the massacre of him by "spiritual shepherds."

In the same year SAKHAROV Ivan Petrovich entered the medical department of Moscow University. After graduating he became a doctor of the postal department in the capital. But, while studying and working, he did not give up studying the history of the Tula region.

It is important to note that SAKHAROV Ivan Petrovich already in the initial period of his activity, he departed from the views of noble historiographers, who perceived the historical process as the result of the deeds of great people. A step forward was his conviction about the connection of this process with the development of the people's beginning in history. Such views of the Tulyak coincided with the concept of the bourgeois enlightenment of N. A. Polevoy, who created, in contrast to N. Karamzin, the History of the Russian People. Their positions were also brought together by their attitude to primary sources, criticism of the nobility, in general, the desire to bring a fresh stream to source studies. Personal contacts have been established. The printing of historical documents began in N. Polevoy's magazine "Moscow Telegraph", which was then, according to V. G. Belinsky, "the best magazine in Russia."

Soon a hardworking and persistent student SAKHAROV Ivan Petrovich finished bringing together the multitude of collected documents. In 1832, he published in Moscow the manuscript of the "History of public education in the Tula province" (though only one part). In the preface, the author noted that his work is an expression of sacred love for the Motherland and the memory of ancestors. After a brief geographical reference, cadastral books of the Tula Posad were given (in retelling) - the most important sources of the economic and social life of the city. The book includes 53 letters. They characterize the feudal tenure of the XVI-XVII centuries.

Of considerable interest are the messages of the sovereigns to the Tula governors, which make it possible to trace the long and difficult path of the formation of state gunsmiths as a special estate with specific rights and privileges.

Publication Sakharov for the first time introduced into scientific circulation materials that are essential not only for our region, but for the entire historical science.

And a year earlier, he published a book from the history of the Tula Posad based on cadastral books - "Sights of the Venev Monastery" - with a dedication to his teacher and mentor I.F. Afremov.

In one of the central journals, A. Glagolev, a member of the Society for the History and Antiquities of Russia, gave an overview of the documents of the first collection on the history of Tulytsina. Thus, its content has become the property of a wide range of readers. Later, Glagolev used them in his works on the history of cities and districts of the province.

Another historian's monograph - "Sights of the city of Tula and its province" - was published only in 1915 in the "Proceedings of the Tula provincial scientific archival commission". For the first time, it proposed a periodization of local history from primitive settlements to the mid-20s of the 19th century. It reflected the important role of Tula in the anti-serfdom movements and the defeat of the Polish intervention, the transformations of Peter I, as a result of which the city became a major industrial and commercial center. Such periodization linked local and all-Russian events into one whole.

SAKHAROV Ivan Petrovich paid attention to the cultural tradition of his native land, publishing a work about writers, educators of the region. He collaborated and made friends with many prominent people. Shortly before his death, A. S. Pushkin shared with Ivan Petrovich his ideas for translating "The Tale of Igor's Campaign", introduced him to the materials found on the "History of Pugachev". In the journal "Sovremennik", published after the death of the poet in favor of his family, the local historian published an excerpt from the "Public Education of the Tula Province".

Publication activity I. P. Sakharova has not lost its significance to this day. It clearly traces the search for a method of local history research.

A huge array of valuable documentation is stored in the state archive of the Tula region in the personal fund of the historian. It includes historical and statistical descriptions of cities and counties, a geographic and statistical dictionary, information about minerals, industry, agriculture, crafts, and trade.

In the history of national culture Ivan Petrovich Sakharov entered primarily as a prolific publisher of the treasures of oral folk art. In the late 1930s and 1940s, he published popular multi-volume works: "Tales of the Russian people about the family life of their ancestors", "Songs of the Russian people", "Journeys of Russian people to foreign lands", "Russian folk tales" and a number of others. They widely used the collections of Tulyaks I. Afremov, brothers Kireevsky, V. Levshin.

In 1840 I. P. Sakharov becomes a teacher at the Alexander Lyceum and the School of Law. On the basis of a course of lectures, he prepared and published the first manual on paleography - a historical and philological discipline that studies the monuments of ancient writing. At this time, he participated in the work of the Archaeological and other scientific societies.

For collecting, researching folklore, ethnography, paleography in 1854, the scientist was elected a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences.

Solid factual material collected I. P. Sakharov, with a critical attitude towards it, it will be very useful in studying the monuments of the "bygone days" of our region.

A. A. Petukhov

Sources and literature:

Ashurkov V.I.P. Sakharov//Tula region. 1930. No. 2 (17).

Prisenko G.P. Penetration into the past. Tula, 1984.

Sakharov I.P. Notes. My memories//Russian arch. 1873. No. 6.

The famous ethnographer-collector, archaeologist and paleographer of the 1830-50s; was born on August 29, 1807 in Tula. His father, Pyotr Andreevich, a Tula priest, placed his son in the local theological seminary, from which he graduated on August 21, 1830. Apparently, there were no outstanding teachers from the seminary. After graduating from the seminary, S. was dismissed from the clergy and entered the Moscow University at the Faculty of Medicine; he graduated in 1835 with the title of a doctor and was assigned to practice in the Moscow City Hospital.

From there he was soon transferred to the university doctors and, having served here for a year, he moved to the service of a doctor in the Postal Department in St. Petersburg, where he moved in February 1836. Here S. worked until the end of his life, making only occasional excursions to the central provinces.

In 1837, at the suggestion of Pogodin, S. was elected a member of the Imp. Society of History and Antiquities of Russia.

In 1841, at the request of Prince A. N. Golitsyn, under whose command S. served in the Postal Department, he received the Order of Stanislav 3rd class, a diamond ring as a gift and an annual pension of 1000 rubles. ass. In 1847, Mr.. S. became a member of the Geographical Society, and in 1848 - Archaeological.

As a member of the latter, S. worked very hard and rendered great service by inviting people to work for the Society who could take up the description of monuments or provide information about them; he looked for tasks for bonuses and found people who were ready to donate money for this; finally, on his initiative, the publication of "Notes of the Department of Russian and Slavic Archeology of the Imperial Archaeological Society" (1851) began, which included many of his own works and materials collected by him.

At the same time, S. took part in the work of the Public Library: he delivered instructions on manuscripts and rare books that should be purchased for the library, he got the manuscripts and books themselves. As a reward for such activities, S. was one of the first to be made an honorary member of the Library (1850). About half of the 50s, S.'s activity began to weaken.

In recent years, he suffered a serious illness, his activity completely ceased, and after suffering for five years, he died (in the rank of collegiate adviser) on August 24, 1863, due to liquefaction of the brain, in his small estate "Zarechye" (Novgorod province., Valdai district ) and was buried at the Church of the Assumption of the Ryutinsky churchyard.

S. zealously collected books and manuscripts.

His bibliophilic gaze penetrated even beyond the boundaries of Moscow and St. Petersburg, and after him there remained an extensive and remarkable collection of manuscripts, like Pogodin's "ancient storage", later acquired by Count A. S. Uvarov.

S.'s literary activity began in 1825, that is, back in the seminary, and was directed, according to S. himself, exclusively to Russian history, but he had nowhere to get historical knowledge: there were not many books in his father's small library about Russian history, five - six. However, he managed to get the history of Karamzin from the priest N. I. Ivanov and, excited by reading it, S. took up local history: he collected materials from everywhere to study it, penetrated the archives of the local monastery and the cathedral church built under Alexei Mikhailovich, and then became to publish in "Galatea", "Telescope" and "Russian Vivliofika" Polevoy materials relating to Tula antiquity.

With a small number of lovers of folk antiquity at that time, the name of S. was noticed from these experiments; for example, Pogodin in his "Telescope" (1832) spoke very favorably of S.'s book "The History of Public Education in the Tula Province" (M. 1832). At the university, medical studies, apparently, did not captivate S. exclusively, since already in 1831 he published a book about the Venev Monastery, and the following year - the above-mentioned History of General Education. But apart from this S. worked in the field of ethnography.

A passion for folk literature awakened in him very early; while still a seminarian and student, he walked around the villages and villages, peered into all classes, listened to Russian speech, collected traditions of long-forgotten antiquity, entered into close relations with the common people and "eavesdropped" on their songs, epics, fairy tales, proverbs and sayings .

For six years S. proceeded along and across several Great Russian provinces (Tula, Kaluga, Ryazan, Moscow, etc.), and he formed a rich ethnographic and paleographic material.

The real and very extensive fame of S. has gone since 1836, using his material, he began to publish "Tales of the Russian people", "Journeys of the Russian people", "Songs of the Russian people", "Notes of the Russian people", " Tales" and a number of bibliographic works on old literature and archaeological research.

The collection and recording of folk literature was just beginning: neither P. Kireevsky, nor Rybnikov, nor Bessonov, and others had yet performed with songs. Manuscripts, monuments of ancient writing rotted in the archives of monasteries and cathedrals.

True, since the end of the last century, collections of folk songs have been published interspersed with the latest romances and arias; but that was so long ago, and the collections of Chulkov, Makarov, Guryanov, Popov and others were already forgotten or completely out of sale.

Meanwhile, since the 1930s, interest in folklore and nationality has been growing tremendously.

Emperor Nicholas sends artists to Vladimir, Pskov and Kyiv to copy and recreate antiquities.

In 1829, the Stroevskaya archeographic expedition was equipped.

Everyone feels that antiquity is unknown to us, that everything folk has been forgotten and must be remembered.

And at such a time of public mood, S. spoke. A whole series of his publications struck everyone with the abundance and novelty of the material: the amount of data he collected was so unexpectedly large and for the most part so new for many, so by the way, with constant talk about nationality, what about he was spoken to everywhere.

And we must do justice - S. showed remarkable diligence, extraordinary enterprise, sincere passion and enthusiasm for everything folk, and in general rendered very great services to Russian ethnography, archeology, paleography, even the history of icon painting and numismatics.

The following list of his writings and publications shows how much he did. But one cannot remain silent about the shortcomings of S.'s work, thanks to which he was forgotten. These shortcomings stemmed, on the one hand, from his views, on the other hand, from insufficient training in the field of history, archeology and ethnography.

He was self-taught in the full sense, since neither the seminary nor the medical faculty, graduated from S., could give him the proper training, those information on history, literature and ethnography, and those methods that are necessary for the collector and publisher of ancient monuments of folk literature .

The lack of preparation was expressed in the unscientific way of publishing works of folk literature.

For example, he almost never indicates where he came from and where this or that song, epic, fairy tale, etc. was recorded. The very system of arranging songs is striking in its disorderliness.

Here is how S. shares Russian songs: 1) Christmas songs, 2) round dance, 3) wedding, 4) festive, 5) historical, 6) daring people, 7) military, 8) Cossack, 9) dance, 10) lullabies, 11) satirical and 12) family.

Already Sreznevsky noticed the disorder in the arrangement of the material and the fact that many of the books of the "Tales of the Russian people" in no sense fit in their content with the concept of the legends of the people.

Finally, S.'s views led him into errors and delusions.

Coming out of the false view of the special perfections of the Russian people and thinking that it should be exhibited in an ideal form, he did not consider it a sin to embellish, change or discard something from songs, epics, fairy tales, etc. On the same basis, demonology and sorcery he does not consider it a product of the Russian people, but recognizes it as a borrowing from the East.

But, what is most amazing of all - S. allowed himself fakes for folk poetry and passed them off as real, original ones.

So, for example, the latest criticism reproaches him for the fact that he composed a fairy tale about the hero Akundin and passed it off as folk.

Thanks to all these shortcomings, the authority of S. fell by the middle of the 50s, when new collections of songs, epics and fairy tales appeared.

Here is a list of his writings, brochures and articles published in magazines: "Galatea", "Moscow Telegraph", "Journal of manufactures and trade", "Contemporary", "Northern Bee", "Literary additions to the Russian Invalid", "Domestic Notes" , "Mayak", "Russian Bulletin", "Moskvityanin", "Son of the Fatherland" and "Journal of the Ministry of People's Education". 1) "An excerpt from the history of the Tula province". (printed in Galatea, 1830, no. 11). 2) A letter to the publisher of the Moscow Telegraph, with the letter of tsar Mikh attached. Fedorovich. (Mos. Tel., 1830, part 32, no. 5). 3) "News about ancient letters" (Mos. Tel., 1830, Articles I and II, No. 8, 16-17). 4) "Two letters of the Moscow Patriarch Joachim to Joseph, Archbishop of Kolomensky and Kashirsky, on the addition to the conciliar act of 1667 of the spiritual decrees of 1675 on May 27th day" (Mos. Tel., 1830, part 36). 5) "News about ancient letters" (Mos. Tel., 1831, Nos. 19-20. This article served as a continuation of the first two, printed in Mos. Tel. 1830). 6) "Diploma of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich" (Mos. Tel., 1831, No. 23). 7) "Scribal Book of Tulsky Posad" (Mos. Tel., 1831, No. 12, part 39). 8) "Sights of the Venev Monastery", M., 1831. 9) "History of public education in the Tula province.", Part 1., M., 1832. With two plans of the city of Tula and a map of the Tula province. 10) In the Russian Vivliofika, published by N. Polev in 1833, Sakharov placed: a) Letters - 13 in total (p. 189). b) Orders - only 7 (p. 265). c) Article inventory of Mtsensk (365). d) Crying and sorrow during the last hours of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich (375). e) Memory of the Tula burgomasters about shaving their beards (381). f) Actual registration on the estate (384). g) The legend of the baptism of Metsnyan (361). h) The bill of sale for the estate of Prince Drutsky (362). 11) Letter to the publisher of the Moscow Telegraph about writers who lived in the Tula province (Mos. Tel., 1833, part 50). 12) "Medical Italian doctrine of anti-excitability", M., 1834. 13) "Tales of the Russian people about the family life of their ancestors." Part I, St. Petersburg, 1836. The manuscript was prepared in Moscow as early as 1835. 14) Experienced People (Pluchard's Encyclopedic Lexicon, vol. VII, 481). 15) "Tales of the Russian people about the family life of their ancestors." Part II, St. Petersburg, 1837. 16) "Tales of the Russian people about the family life of their ancestors." Ed. 2nd, part I, St. Petersburg, 1837. 17) "Journeys of Russian people to foreign lands". Ed. 1st, part I, St. Petersburg, 1837 (with a photograph from the manuscript). 18) "Journeys of Russian people to foreign lands". Part II, St. Petersburg, 1837 (with a photograph from the manuscript). 19) "Journeys of Russian people to foreign lands". Ed. second, part I, St. Petersburg, 1837. 20) "Tales of the Russian people about the family life of their ancestors", part III, book. 2, St. Petersburg, 1837. 21) "On Chinese Trade" (in the Journal of Manufacture and Trade, then published by Bashutsky, 1837). From this article, P. P. Kamensky made his own and published it in his own way in Russkiy Vestnik. 22) "Public education of the Tula province" (Sovremennik, 1837, part VII, 295-325). 23) "Mermaids" (Northern Bee, 1837). 24) Review of the book: "On delusions and prejudices". Op. Salvi, trans. S. Stroeva. (Literary Addition to the Russian Invalid, 1837). 25) In Plushard's Encyclopedic Lexicon, the following was placed. articles by Sakharov: a) Belevskaya Zhabynskaya hermitage (vol. VIII, 520). b) Belevskaya clay (VIII, 520). c) Belevsky princes (VIII, 521). d) On book printing in Vilna (VIII, 238). e) Cherry trees (X, 574). f) Whirlwinds (X, 489). 26) "The First Russian Typographers" (in the Collection published by A. F. Voeikov). 27) "Biography of I. I. Khemnitser" (with the latter's fables). 28) "Biography of Semyon Ivanovich Gamaleya" (Northern Bee, 1838, No. 118). 29) "Werewolves" (Northern Bee, 1838, No. 236). 30) "Divination Russians" (Encyclopedic Lexicon, XII, 55). 31) "Writers of the Tula province", St. Petersburg, 1838. 32) "Songs of the Russian people", part I, St. Petersburg, 1838 (with a historical overview of the collection of folk poetry). 33) "Songs of the Russian people", part II, St. Petersburg, 1838. 34) "Russian Christmas time" (Literary Addition to the Russian Invalid, 1838, No. 4). 35) Reviews of books printed in Lit. Additions to the Russian Inv.: a) Review of the book: "Anatomy", op. Hempel, No. 5. b) "Monograph of the radical treatment of inguinal-scrotal hernias", No. 6. c) "On diseases of the uterus", Op. Gruber. No. 50. d) On the Main Causes of Nervous Diseases, No. 50. e) Heads of the Foundation of Pathological Anatomy, Op. D. Gona, No. 20. 36) "Relations of the Russian Court with Europe and Asia in the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich" (Domestic Notes, 1839, vol. І, sec. II, 47: only the 1st half was printed, and the second was given to the editor ). 37) "The Russian Scientific Society in the 17th Century" (Almanac Morning Dawn, 1839). 38) "Vasily Buslaevich.

Russian folk tale" (Printed in the book: "New Year", published by N. V. Kukolnik). 39-41) "Songs of the Russian people", part III-V, St. Petersburg, 1839. 42) "Slavic-Russian manuscripts ", St. Petersburg, 1839 (printed in a collection of 50 copies and was not put on sale). 43) "Modern Chronicle of Russian Numismatics" (Northern Bee, 1839, Nos. 69-70. The article is continued: Numismatic collections in Russia, No. 125. 44) "Tales of the Russian people", 3rd edition, vol. І, books 1-4, St. Petersburg, 1841. 45) "Notes of Russian people", events of the time of Peter the Great.

Notes of Matveev, Krekshin, Zhelyabuzhsky and Medvedev, St. Petersburg, 1841. 46) "Russian folk tales". Part I, St. Petersburg, 1841. 47) "Chronicle of Russian Engraving" (Northern Bee, 1841, No. 164). 48) "Ilya Muromets". Russian folktale. (Mayak, 1841). 49) "About Ersh Ershov, son of Shchetinnikov". Russian folktale. (Literary Gazette, 1841). 50) "Ankudin". Russian folk tale (Northern Bee, 1841). 51) "About seven Semions - native brothers". Russian folk tale (Notes of the Fatherland, 1841, No. 1, vol. XIV, section VII, pp. 43-54). 52) "Description of images in the royal large chamber, made in 1554" (Notes of the Fatherland, 1841, No. 2, vol. XIV, sec. VII, 89-90). 53) "On Libraries in St. Petersburg" (Notes of the Fatherland, 1841, No. 2, vol. XIV, section VII, pp. 95-96). 54) "Chronicle of Russian numismatics". Ed. 1st, St. Petersburg, 1842, with app. 12 shots. The 2nd edition of this book was printed in 1851. 55) "Russian Ancient Monuments". SPb., 1842. With 9 photographs from early printed books. 56) Review of the book "Description of early printed Slavic books, serving as an addition to the description of the library of Count F.A. Tolstoy and merchant I.N. Tsarsky". Published by P. Stroev. (Literaturnaya Gazeta, 1842, No. 22-23). 57) "Literary legends from the notes of an old-timer" (Literaturnaya Gazeta, 1842, No. 30). 58) "Secret information about the strength and condition of the Chinese state, presented to Empress Anna Iv. by Count Savva Vladislavovich Raguzinsky in 1731" (Russian Bulletin, 1842, No. 2, 180-243, No. 3, 281-337). 59) "Russian translations of Aesop's fables at the beginning and end of the 17th century" (Russian Bulletin, 1842, No. 2, 174-179). 60) "Russian ancient dictionaries" (Notes of the Fatherland, 1842, vol. XXV, sec. II, 1-24). 61) "Marco rich". Russian folktale. (Sev. Bee, 1842, Nos. 3-5). 62) "Historical Notes" (Sev. Bee, 1842, No. 108). 63) "Iberian Printing House" (Sev. Bee, 1842, No. 157). 64) "Blumentrost's medical book" (Mayak, 1843, No. 1, vol. VII, ch. 3, 67-74). 65) "Several instructions for the Slavic-Russian old people" (Mayak, 1843, No. 1, vol. VII, 21-74. Here are extracts from George Amartol). 66) "Belev" (Mayak, 1843, No. 4, vol. VIII, 50-57). 67) Notes on the book "Kiev", part 2. Ed. M. Maksimovich (Mayak, 1843, No. 2, vol. VII, 155). 68). "Decree book of Tsar Mikhail Feodorovich and boyar sentences on patrimonial and local lands" (Russian Bulletin, 1842, Nos. 11-12, p. 1-149). 69) "Catalogue of the library of the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery" (Russian Bulletin, 1842, No. 11-12). 70) "Tsar John Vasilievich - a writer" (Russian Bulletin, 1842, Nos. 7-8, p. 30-35). 71) "Historical Notes" (Moskvityanin, 1843, No. 9). Articles are placed here: a) For Russian numismatists. b) "On the sources of Russian chronicles". c) "About the children of Staritsky prince Vladimir Andreevich". d) "About Sylvester Medvedev". e) "About Kurbsky". f) "On the Word of Daniel the Sharpener". g) "About Stefan Yavorsky". 72) "Letter to M.P. Pogodin" (Moskvityanin, 1843, No. 10). 73) "Moscow appanage princes" (Son of the Fatherland, 1843, edited by Masalsky.

Here is printed a summary text about these princes from genealogical books). 74) Letter to the publisher of Mayak (Mayak, 1844, No. 3, vol. XIV). 75) Letter to the publisher of "Moskvityanin" (Moskvityanin, 1845, No. 12, sec. I, 154-158). 76) "Historical Notes" (Sev. Bee, 1846, Nos. 11-13). Articles are placed here, titled: a) Anthony, Archbishop of Novgorod. b) A. Kh. Vostokov and N. G. Ustryalov-Savvaitov. 77) "Russian church chanting" (Journal of Min. N. Pr., 1849, No. II-III, sec. II, pp. 147-196, 263-284; No. VII, sec. II, pp. 1-41) . 78) "Tales of the Russian people". Vol. II, books 5-8. 79) "Review of the Slavic-Russian Bibliography". T. I, book. 2, no. IV. 80) "Research on Russian icon painting". Ed. 1st, part I. 81) Programs were written for the Archaeological Society on the debate proposed by the members: c. A. S. Uvarov, Yakovlev, Kuzmin, Shishkov, Lobkov, Kudryashov.

All of them were published in Zap. Arch. Tot. and in the newspapers. 82) "Research on Russian icon painting". Part II, St. Petersburg, 1849. 83) "Research on Russian Icon Painting". Part I, Ed. 2nd. 84) "Money of the Moscow appanage principalities", St. Petersburg, 1851. 85) "Note for the review of Russian antiquities", St. Petersburg, 1851. Issued in 10 thousand copies, written for Arch. Society, when the Russian branch was formed, and was sent everywhere without money. 86) "Review of Russian Archeology", St. Petersburg, 1851. 87) "Russian Trade Book", St. Petersburg, 1851. 88) "Notes on a critical review of Russian numismatics" (Notes of the Arch. General, vol. III, 104-106 ). 89) "On the collection of Russian inscriptions" (Zap. Arch. General, III). 90) "Russian antiquities: brothers, rings, rings, dishes, buttons" (Zap. Arch. General, vol. III, 51-89). 91) "Notes of the Department of Russian and Slavic Archeology of the Imperial Archaeological Society". T. І, St. Petersburg, 1851. These notes were compiled from the works of members of the department. 92) "The program of Russian legal paleography" (There were three editions: one for the School of Law and two for the Lyceum, and all are different in content). 93) "Lectures of Russian legal paleography". For the Lyceum, these lectures were lithographed under the title: Readings from Russian paleography.

Only the first part was printed. In the "Northern Bee" from the third part, an article was printed: Russian monetary system.

At the School of Jurisprudence, the lectures were not printed, and the reading was offered more extensively than the lyceum.

For jurists it was printed in a special book. 94) "Snapshots from the court letter of Russian, Lithuanian-Russian and Little Russian" (printed in the number of 40 copies, it was not published, but served as a guide for pupils when reading legal acts). 95) "Notes on Russian coats of arms.

Coat of arms of Moscow". St. Petersburg, 1856. With three tables of photographs. (The second part - On the All-Russian coat of arms - was transferred for printing to the Western Arch. Society). "Russian Archive", 1873, p. 897-1015. (Memoirs S., reported by Savvaitov) - "Ancient and New Russia", 1880, No. 2-3 (N. Barsukov, "Russian paleologists". Here is Sakharov's correspondence with Kubarev and Undolsky and a short biography) - "Notes Acad. Nauk", 1864, book 2, p. 239-244 (Sreznevsky: Recollection of S.). - "Russian Archive", 1865, No. 1, p. 123 (Gennadi, "Information about Russian writers) . - "Illustrated newspaper", 1864, No. 1, p. 1 (with a portrait of S.). - "Tula Diocesan Vedomosti", 1864, No. 5. - Panaev, "Memoirs", p. 117 (St. Petersburg, 1876). - Pypin, "History of Russian Ethnography", St. Petersburg, 1890, vol. I, 276-313. - Ap. Grigoriev in "Moskvityanin", 1854, No. 15, p. 93-142. - "Songs" collected by P. Kireevsky.

Issue. 6, M., 1864, p. 187-190; issue 7, 1868, p. 111-112, 137, 146-147, 206-212; issue 8, 1870, p. 2, 24, 28, 58, 61, 65-75, 78-80, 84, 85, 87, 88, 90-93, 97, 132-134, 154, 155, 161, 284, 285, 302, 319; in Bessonov's note - p. LXVIII. - Zabelin, "Experience in the study of Russian antiquities and history". T. I-II, 1872-1873. - Barsukov, "The Life and Works of Pogodin", vol. IV-VII according to the index. - "Proceedings of the 1st Archaeological Congress", M., 1871, I (Pogodin on the works of S.). - "Telescope", 1832, No. 10, p. 237-252. No. 2, p. 192-207 (Pogodin about "The historical general image of the Tula province."). - "Library for Reading", 1849, vol. ХСІV, 1-81, 81-118, XCV, 1-37 (Stoyunin, Review of "Tales of the Russian people"). E. Tarasov. (Polovtsov) Sakharov, Ivan Petrovich (1807-1863) - famous ethnographer, archaeologist and bibliographer; son of a Tula priest, a graduate of the Moscow Univ. in the Faculty of Medicine, a doctor at the Moscow City Hospital, a teacher of paleography at the School of Law and the Alexander Lyceum, a zealous figure in geographer societies. and archaeological.

His main works: "History of public education of the Tula province." (M., 1832), "Tales of the Russian people" (M., 1836-37; 2nd ed., 1837; 3rd ed., St. Petersburg, 1841-49), "Journeys of Russian people to foreign lands" (St. Petersburg, 1837; 2nd ed., 1839), "Songs of the Russian people" (ib., 1838-39), "Writers of the Tula province." (ib., 1838), "Slavonic Russian manuscripts" (ib., 1839), "Russian folk tales" (ib., 1841), "Notes of Russian people" (ib., 1841), "Russian ancient monuments" (ib. , 1842), "Studies on Russian icon painting" (ib., 1849), "Review of the Slavic-Russian bibliography" (ib., 1849), "Note for the review of Russian antiquities" (ib., 1851), "Note on Russian coats of arms . I. Moscow coat of arms" (ib., 1856). S.'s "Memoirs" were published after his death in the "Russian Archive" in 1873, 6. After him, an extensive and remarkable collection of manuscripts, acquired by Count A.S. Uvarov, remained.

Until the middle of the 1850s. the name of S. and his publications were very popular; his works were considered among the authoritative sources for scientific and literary conclusions about the Russian people.

Now quotations from S.'s publications are very rare: criticism took a different look not only at his opinions, but also at the very quality of many of the texts he cited, and rejected them as inaccurate or even false.

However, for his time S. was a remarkable archaeologist and ethnographer.

In his first capital works: "Tales of the Russian people", "Travels of the Russian people", "Songs of the Russian people", etc., he showed remarkable industriousness and enterprise; going towards the first awakened desire to study the Russian people, he made, according to I. I. Sreznevsky, an extraordinary impression on the entire educated society, causing him "strong respect for the Russian people." The shortcomings of S.'s work came from the fact that he was self-taught, a dogmatist, alien to historical criticism.

See about him "Memoirs" by I. I. Sreznevsky ("Notes of the Imperial Academy of Sciences", 1864, book 2); "For the biography of S.", with excerpts from his memoirs ("Russian Archive", 1873, 6); Pypin, "History of Russian Ethnography" (vol. I, St. Petersburg, 1890). V. R-v. (Brockhaus) Sakharov, Ivan Petrovich archaeologist; genus. Aug 29 1809, † 24 Aug. 1863 (Polovtsov)