The evolutionary theory of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Pierre de Chardin - biography, information, personal life. Archeology and paleontology

Introduction

The path of "The Phenomenon of Man" from writing to publication

The main ideas of "The Phenomenon of Man"

Evolutionary-biological content of "The Phenomenon of Man"

Philosophical Problems in The Phenomenon of Man

Conclusion

List of sources used

Introduction

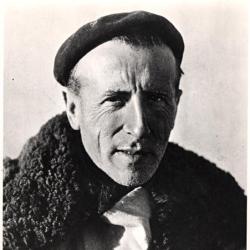

The years that have passed since the death of Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955) were filled with fierce controversy surrounding his name. The books of this outstanding scientist, published posthumously, caused reactions, often diametrically opposed. If some call him "the new Thomas Aquinas", who in the 20th century. again managed to find approaches to gaining the unity of science and religion; others characterize his teaching as a "falsification of faith" (Gilson), "a substitution of Christian theology for Hegelian theogony" (Maritin) (1). The result was the procedure for the removal of T.'s books from the libraries of seminaries and other Catholic institutions and the decree of the office of the Vatican dated 30.6.1962, calling for the protection of Catholic youth from the impact of his work. However, no matter how one evaluates Teilhard and his worldview, no one can deny that he is a highly significant and symptomatic phenomenon. His work has been studied with great interest and is being studied in the world from various angles and from various points of view. Historians of science argue about the plausibility, value and prospects for further thinking through that all-encompassing picture of the development of the Universe, which Teilhard created “piece by piece” throughout his life.

Natural scientists still use his research in several areas at once: general and historical geology, geomorphology, paleontology, paleoanthropology.

It answers many questions that concern thinking people today. Science and religion, evolution and the coming transformation of the world are intertwined in his "Phenomenon of Man" into a single living whole. A naturalist and a priest, a poet and theologian, a thinker and a mystic, a brilliant stylist and a charming person - he was, as it were, created in order to become the ruler of the thoughts of current generations. Catholics are proud of him, communists publish his books, although both are far from fully accepting his teachings. Such is the power of its attraction.

Creativity T. multilevel and diverse. The work "The Phenomenon of Man" is devoted to the problem of the relationship between science and religion, the issues of evolution and the future transformation of the world, the image of the "converging" Universe, the presentation of the foundations for seeing the world as a living organism, permeated by the Divine and striving for perfection.

1. The path of "The Phenomenon of Man" from idea to publication

creative phenomenon religion shardin

In 1923 he went on a research expedition to Tianjin (China). During the expedition, in the Ordos desert, he wrote several articles and essays, in 1926-1927 Teilhard wrote the book "The Divine Environment", but he was not allowed to print philosophical works, so Teilhard again travels to China, India, Burma. Java, Africa and China again. There, in the embassy quarter of Beijing, Teilhard overtakes the war: Japanese troops in 1937 occupy the Chinese capital. Left in isolation for many years, he continues to develop his teaching and creates his main work - "The Phenomenon of Man".

With the finished manuscript of The Phenomenon of Man, he returned to France in 1946, but getting permission to publish it turned out to be a hopeless affair (2). The last attempt in this direction was made by Teilhard in 1947, having reworked the "Phenomenon" in the form of a variant with the removal of the sharpest points. In the autumn of 1948 Teilhard visited Rome. He tried to obtain permission from the papal curia to publish, if not the Phenomenon itself, then at least its fragments under the title The Zoological Group of Man. However, this trip did not give the desired result. Then Teilhard introduces an additional chapter into the book in the form of an epilogue: "The Christian Phenomenon". In it, he (as if forgetting about the phenomenological attitude repeatedly emphasized in the book and about the rejection of theology in this work) introduced transcendental objects that had not even been mentioned before and gave such a variant of ontology for which one could hope to get permission.

Hope proved unfulfilled, since even in this additional chapter there are many places that looked "suspicious and unorthodox."

All this, as it is easy to understand, did not help to remove the accusations of anti-doctrinalism. Teilhard's main work remained under wraps.

Teilhard was not allowed to take a chair at the College de France, where he was respectfully invited. Even Teilhard's election to the Paris Academy of Sciences in 1950 did not change the prejudice of church hierarchs against his ideas. Teilhard again was not given permission to speak on the problems of philosophy, and in 1951-1954. it is even forbidden to travel to Paris, in this regard, he accepted an offer related to work in the USA and leadership of excavations in Africa, especially since just in these years newer data were received on finds that connected him even more closely with the world of primates.

But Teilhard was no longer destined to use these data to deepen the picture of the "phenomenon of man", before his death he only managed to make two trips to the countries of South Africa.

The beginning of the posthumous publication of the collected works of Teilhard made a considerable impression and at the same time brought new condemnations to the author. Their series began with the removal of books from the libraries of seminaries and other Catholic institutions (1957) and a decree of the Vatican Chancellery, headed by Cardinal Ottavini, of June 30, 1962, calling for the protection of Catholic youth from the impact of Teilhard's work.

2. The main provisions of the "Phenomena of Man"

Descendant of Voltaire, who was the great-uncle of his mother Teilhard Author of the concept of "Christian evolutionism". Professor of Geology at the Catholic University of Paris (1920-1925). Member of the Paris Academy of Sciences (1950). Creativity T. multilevel and diverse. Teilhard de Chardin has always emphasized the interconnection of all sciences. He dreamed of a kind of super-science coordinating all branches of knowledge. In this context, Teilhard interpreted the special significance of religion, because science needs the conviction that "the universe has a meaning and that it can and must, if we remain faithful, come to some kind of irreversible perfection", from his point of view: ".. We certainly realize that something greater and more necessary is going on within us than ourselves: something that existed before us and perhaps would exist without us, something in which we live and which we do not we can exhaust; something that serves us, despite the fact that we are not its masters; something that gathers us together when, after death, we slip out of ourselves, and our whole being, it would seem, disappears. For a genuine breakthrough in the comprehension of these problems, according to Teilhard, it is necessary to acquire a deep intuition of unity and the highest goal of the world. In this sense, religion and science appear as two inextricably linked sides or phases of the same complete act of knowledge, which alone could encompass the past and future of evolution. (Attempts to determine approaches to obtaining truly integral knowledge are not new to the history of philosophy - Aristotle's theoretical refinements on this topic are known, the idea of \u200b\u200b"free theosophy - integral knowledge" by V. Solovyov and many others.) Building a scheme of the architectonics of the development of planetary existence, Teilhard designated its stages as "pre-life" (or "sphere of matter" - lithosphere/geosphere), "life" (biosphere) and "human phenomenon" ("noosphere").

Teilhard de Chardin's mystical interpretation of matter, the phenomena of creativity, human activity - apparently, were close to the worldview of Christianity, but they were expounded by him through the prism of his deeply intimate, personally-colored experience. Teilhard was close to the idea that the commodity world was able to rise to the noblest levels of perfection due to the fact that Christ was not God, who took the form of an earthly being, logical selection and invention, mathematics, art, the measurement of time and space, love anxieties and dreams - all these types of inner life are in fact nothing but the seething of the newly formed center at the moment when it blooms in itself. "Further, according to Teilhard, from the noosphere will develop "love, the highest, universal and synthetic form of spiritual energy in which everything other soul energies will be transformed and sublimated as soon as they enter the "Omega area"). He was able to substantiate, in the context of his concept, a completely unique interpretation of humanism (in terms not so much of the degree of postulated anthropocentrism as of the degree of minimally predetermined mercy): “How could it be otherwise if the Universe must be kept in balance? Superhumanity needs a Super-Christ. Super-Christ is in need of Super-mercy... At the present moment there are people, many people who, having united the ideas of the Incarnation and evolution, have made this unification a real moment of their lives and successfully carry out the synthesis of the personal and the universal. and serve evolution, but also love it; thus they will soon be able to say directly to God (and it will sound familiar and will not cost people any effort) that they love Him not only with all their heart and soul, but also Teilhard's grandiose intellectual-religious model, organically including the ideas of "superlife", "superhumanity", "planetization" of mankind, allowed him to supplement the purely religious characteristics of the noosphere with its truly informative description: "A harmonized community of consciousnesses, equivalent to its kind of superconsciousness. The Earth is not only covered with myriads of grains of thought, but is enveloped in a single thinking shell, functionally forming one vast grain of thought on a cosmic scale.

. Evolutionary-biological content of "The Phenomenon of Man"

Teilhard's evolution is invariably in the foreground, and its significance is emphasized with extreme sharpness. Perhaps more insistently than anyone else, Teilhard emphasizes that evolution is not limited by the framework of living nature, that “starting from its most distant formations, matter appears before us in the process of development” (3). At the opposite end of the evolutionary ladder, in social structures, Teilhard also does not see a real pattern of movement. The most constructive part of Teilhard's doctrine of development is that which is connected with the biological level and its transformation into a "human phenomenon".

Teilhard's relationship between the "inner world" and the outer world is described similarly to Spinoza's idea that the soul's awareness of objects is richer the more complex it is. The difference between Teilhard's concept is due to the fact that Teilhard tries to separate his images of "internal" and "external" through the concepts of radial and tangential energy and the increase in complexity occurs in evolutionary series.

Undoubtedly, the continuity of Teilhard's works with the ideas of Diderot, Voltaire and other encyclopedists in relation to issues affecting the field of evolutionary biology. Evolutionary ecology did not escape the impact of intuitionism and other irrational tendencies of his time.

It is no coincidence that the only place in The Phenomenon of Man that speaks of the "elements of consciousness" as the underlying "elements of matter" at the same time affirms the parallelism of the development of both in duration, and not in time.

Evil, according to Teilhard, is primarily human suffering, but it is a necessary incentive for the human race to improve, evil is disunity, gradually overcome by the process of evolution, up to future stages of human development. This overcoming is accomplished through suffering.

The introduction of an evaluative moment into the process of deployment of evolutionary potentials, from the early stages to the highest (human, social, noospheric) phases, is a controversial and at the same time important place in Teilhard's scheme.

By overemphasizing the role of a single pivotal lineage in evolution, Teilhard ends up uniting the real diversity of phylogenesis, which was early divided into eukaryotes and prokaryotes, then plants and animals, and so on. Out of Teilhard's field of vision remains the entire general evolution of plants, not to mention fungi, which are isolated in a separate kingdom.

Teilhard's contribution to the doctrine of the biosphere is also associated with ideas about it as a biota, ultimately monophyletic, which appeared as a result of one "pulsation". The fate of this biota is essentially reflected in both parts of the name "bio-sphere": it is the life shell of the Earth and it is a sphere that does not let its components go far from itself.

Teilhard's tradition is, first of all, a philosophy of nature, continuing the traditions of natural philosophy, this historically earliest form of philosophy in general (4).

4. Philosophical problems in The Phenomenon of Man

In the "prologue" Teilhard warns that in his book one should not look for the ultimate explanation of the nature of things - some kind of metaphysics. It would be expected, and so it is, that there are also attempts to outline a "third line" that would overcome the incompatibility of the first two. First of all, it is a call for "the union of reason and mysticism" (5) or science and religion, since there are more subtle differences between "reason", "science" and "knowledge", as well as between "mysticism", "religion", and " worship” Teilhard does not conduct. Teilhard portrays the forces of human culture as "converging" towards a higher unity called the Spirit of the Earth.

Teilhard sees matter as full of possibilities for development, generation, going beyond: potencies, which he calls in his metaphorical language "divine", "transcendent", etc. The relation of matter to spirit is a relation of primacy, at least insofar as Teilhard does not raise the question of any creation of matter: "matter is the mother of spirit, spirit is the highest state of matter."

In The Phenomenon of Man, in the sense of the infinite and indestructible foundation of the world, the term “fabric of the universe” is used, and matter is actually identified with substance.

Teilhard believes that essentially any energy is of a psychic nature, but divides any fundamental energy into two components: tangential (which connects a given element with all other elements of the same order) and radial energy (which draws it in the direction of an increasingly complex and internally concentrated state) (6). The tangential energy is "the energy commonly accepted by science" and corresponds to motions within a single turn of a "uplifting spiral" or motions on the surface of a sphere. Radial energy leads to a transition to new turns of the spiral or to an expansion of the sphere, to an increase in the level of organization. By radii, each element of this sphere is connected with the center of it and all spheres, with the “sun of being”, with the mystical point “Alpha”, which is somehow the point “Omega” located in the opposite direction, at an infinite distance from the surface of the sphere. Obviously, Teilhard vacillated between attributing to Omega the role of a kind of ultimate concept or Kantian ideas of reason, for which there is no corresponding object in experience (these are the ideas of the soul, the world as a whole, God), but which nevertheless regulate cognition, and the fact that give Omega an ontological status. Thus, Omega acts as a "pole of attraction" for radial energies.

The conceptual apparatus in the field of civil history and prediction is the same radial and tangential energies as in the field of prehuman and human evolution; At the same time, human nature is conceived as a kind of invariant, and this is already a discrepancy with the real state of affairs, which consists in the fact that "the whole history is nothing but a continuous change in human nature."

The noosphere for Teilhard is a part of nature, and it is not for nothing that he does not even use the term “culture” in The Phenomenon of Man.

Teilhard's conclusions are passive, they do not give an incentive to choose one or another "scenario", which still ends with the predetermined triumph of the "Omega point". The constructiveness of Marxist forecasts lies not in optimism or in general an evaluative moment in itself, but in their orientation towards struggle, towards an active position, primarily at the social level.

Of course, in individual cases, a more complete assimilation of materialist dialectics by Teilhard's adherents or their groups is also possible. But in these cases, we are already dealing with a scientific-materialistic approach to a particular problem.

Nevertheless, in the teachings of P. Teilhard de Chardin, thanks to the human optimistic and noble impulse with which it is imbued and which animates him; by recognizing that the specificity of the human phenomenon does not in the least exclude the historical origin of consciousness; thanks to his categorical, without any innuendo assertion that human history makes sense, and his condemnation of the individualistic despair of decadent thinkers, there is a lot of scientific value (7).

Conclusion

Among specialist scientists, inspired theologians, and wise philosophers, it is extremely rare to find a universal thinker or even a truly interdisciplinary creator-researcher. It is extremely difficult to trace the interrelationships and interactions of the most diverse spheres, areas and dominions of culture, but it is even more difficult to connect the practically incompatible, to create something new as an organic alloy of extremely heterogeneous components. In this sense, the figure of Teilhard de Chardin is perhaps unique: he managed to manifest himself simultaneously in science, philosophy, religion and synthesize in his concept a whole series of completely, at first glance, incompatible ideas.

Although Teilhard did not leave direct students and did not create a special school, his teaching was so famous that it gave rise to a whole current of thought that bears his name and is grouped around a special journal. According to Fr. Alexander Men, the works of Teilhard not only teach us a loving attitude towards the world and contribute to the construction of a holistic Christian worldview, but also help the dialogue of Christians with non-Christians. Of all the theological doctrines, it is Teilhardism that, thanks to its broad evolutionary approach, is symptomatic of unorthodox diamatism: Teilhard was the only modern Western theologian whose work was published in the USSR. Teilhard's fame has even extended into the realm of the arts: it is significant that Dan Simmons' sensational sci-fi epic about Hyperion suggests the validity and relevance of Teilhardism even in the very distant future...(8)

Teilhard de Chardin died in New York of a heart attack on April 10, 1955, on Easter Sunday. A year earlier, at a reception at the French consulate, he had said to his close friends: "I would like to die on Easter, on the day of Resurrection" (9).

After the death of Teilhard de Chardin, a commission was created, which included many of his friends, including prominent scientists (A. Breuil, J. Huxley, A. Toynbee, M. Merleau-Ponty, and others). The commission compiled and prepared for publication a ten-volume collected works, which included almost all of his works, with the exception of letters and some essays. The collected works were opened in 1957 by The Phenomenon of Man.

List of used literature

1. A.A. Gritsanov Philosophical Dictionary

2. Teilhard de Chardin. Images et paroles, 1966

3. P. Teilhard de Chardin "The Phenomenon of Man", M: Nauka, 1987, p. 51

B.A. Starostin "From the phenomenon of man to human essence"

P. Teilhard de Chardin "The Phenomenon of Man", M: Nauka, 1987, p. 225

P. Teilhard de Chardin "The Phenomenon of Man", M: Nauka, 1987, p. 61

Roger Garaudy "Teilhard Method"

Vasily Kuznetsov "Teilhard de Chardin: the desire of the living organism of the world for divine perfection."

Ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teilhard_Chardin

Tutoring

Need help learning a topic?

Our experts will advise or provide tutoring services on topics of interest to you.

Submit an application indicating the topic right now to find out about the possibility of obtaining a consultation.

(Teilhard de Chardin) (1881-1955) ? French anthropologist, paleontologist and cosmist theologian, who combined Christianity and Evolutionism in his teaching, author of the theory of the noosphere (along with E. Le Roy and V. Vernadsky) (see Noosphere, Vernadsky). After graduating from the Jesuit college, he takes a monastic vow and becomes a member of the order. In 1913 he began to work in Paris. Institute of human paleontology. In 1920, having defended Dr. dis., becomes prof. Department of Geology Paris. Catholic university Forced to leave the university because of his understanding of certain dogmas, T. goes to paleontol. and geol. expedition to China (1923). For many years of work in China and Mongolia T. published a lot of work that put him in a number of leading paleontologists in the world. During the Second World. war T. wrote published posthumously (the order prevented publication) book "The Phenomenon of Man". In this book, as well as in “Favor. thoughts” and theol. work "Divine Wednesday" (1926-1927) T. outlined his views on the importance of man in the evolution of the universe with t. sp. Christ. pantheism and panpsychism. Culturological the concept of T. is based on a combination of the Divine and evolutionary. theories of the origin and development of culture. Following Thomas Aquinas, he argues that there cannot and should not be contradictions between religion and science, for truth is one and its nature is Divine. Moreover, science without religion is not capable of qualitatively changing the human being. about. T.'s approach is associated with the ideas of the Neoplatonists about emanation and Nicholas of Cusa about the expansion of God into the world and the folding of the world in God. The starting point of his cultural studies. concept - free will, bestowed by God on all his creations in general and man in particular. On Earth, man has become the creator and bearer of culture. He won the right and duty to realize the Divine plan in the course of a long evolution. struggle, to-ruyu were his distant ancestors with representatives of other species. Culture is perceived by T. as a process of animation, and then the “deification” of matter. It is only thanks to culture that it becomes possible to improve the human being. nature, elevate the created spirit and “lead it into the depths of the Divine environment”. According to T., the origins of the teleological nature of our culture go back to the bottomless past. We inherit a life “already amazingly developed by the totality of terrestrial energies” and permeated by the flow of cosmic. influences. Despite the fact that cultural genesis in T. practically merges with cosmogenesis, the development of culture goes through a number of regular stages and has a completely defined definition. goal: several billion years ago, “due to some incredible event”, our planet began to form from a part of matter that had broken away from the Sun. Her substance, passing a series of follow. transformations along the way of complicating their own. organization (crystallization, polymerization, etc.), formed on its surface first a pre-biosphere, and then a biosphere. The emergence of microorganisms and megamolecules on Earth leads to a “cellular revolution” and, then, to the appearance of growth. and animal diversity. “Branches of live weight”, determined by the competition otd. individuals and entire species among themselves, pursue the goal of forming creatures that can most fully embody the plan of God. This idea is to create a species that would realize its purpose. Because the solution of this problem requires a great concentration of mental and mental efforts; these principles became most complete in def. the moment to answer the detachment of primates and, in particular, the genus of man that emerged from it. With the advent of man, the Earth “changes its skin” and, moreover, acquires a soul. But the evolution does not end there. T. distinguishes four stages of Divine Providence: pre-life, life, thought, super-life. In present while humanity is in the third stage of development and its task is to find ways to enter the fourth, concludes. phase, which should lead him to unity with God. Using the apocalyptic terminology, T. designates God as Alpha and Omega cosmic. (and human, in particular) development. Culturological the concept of T. is eschatological: the origins of culture originate from Alpha and end in Omega. Culture is unity. sphere of human manifestation. souls and thoughts. It fixes, consolidates all spiritual quests and minds. achievements of mankind; enables new generations, using previous experience, to move towards God. Understanding Omega (the point of confluence of humanity with God) as the highest goal of human. culture, T. does not believe that its achievement will happen automatically. The freedom of will granted to a person must be consciously directed towards this. Otherwise, humanity will carry out evolution. a step that will again immerse people in supermatter, i.e. lead to evolution. dead end. God does not need creative fruits. activity of people, he is only interested in whether a person will correctly use the freedom granted to him and whether he will give God his preference. The earth in this sense is likened to “test. platform to see if we can be transferred to Heaven.” If the axis of the evolution of the Earth passes through man, then the axis of cultural genesis T., in full accordance with the ideas of Eurocentrism, considers Zap. civilization. It was in the Mediterranean that a “new humanity” arose over the course of six millennia, it was in the West that all the most significant human discoveries were made. culture. The achievements of other cultures acquired their final value only by being included in the European system. representations. The most important changes in human development civilizations and cultures, according to T., occurred in the end. 18th century Only recently about-in, Ch. arr., Western-European, began to move along the path of creating a universal human. civilization, which is the first means. step towards Omega. The emergence of such a civilization is unthinkable without the creation of a world culture that would unite all people. A world culture implies a single religion. According to T., in present. time, signs of convergence of religions are already noticeable, which in the future will lead to their convergence in the Universal Christ and the achievement of Omega. T. connects progress along the path of creating a global religion and culture with “natural. merging grains of thought” of each person into a single sphere of reason - the noosphere. Only in this case will the “formation of the spirit of the Earth” become “biologically” possible. The spirituality of the planet can only be achieved if they finish. deliverance of man. culture from egocentrism, racism and filling it with the energy of love, which transforms “personalization into totalization”. Only in this way can humanity resolve the crisis that began in the Neolithic and is approaching in the 20th century. to its maximum crisis, which consists in the fact that peoples and civilizations have reached such a degree of peripheral. contact, economy interdependence and psychic generality, "that they can grow further only by interpenetrating each other." The further development of the human culture, a swarm of T. gives the planetary and cosmic. meaning, he associates with the "organization of scientific research, focusing them on man, the combination of science and religion." Through these three components, culture will acquire an increasingly collective and spiritual form, which will lead it, upon reaching its highest point, to a natural end, i.e. merging with God. Just as the consciousness of the ancestors of people, more and more concentrated, having reached the “boiling point”, turned into reflection and the Earth acquired a soul with the advent of man, so the end of the world T. thinks as an internal. the concentration of the entire noosphere, as a result of which the consciousness that has reached perfection will separate from its material shell in order to unite with God. At the same time, T. admits that a split of the noosphere into two parts, divided in the question of form, can also occur. T. calls them zones: the zone of thought and the zone of all-encompassing love. This will be the last evolution. branching. That part of the noosphere that can be carefully synthesized through time, space and evil to the end, will reach the Omega point. The rest of the future humanity, having made a choice in favor of the continuation of material evolution, will eventually have to share the death of the materially exhausted planet. Op.: Sur le bonheur. R., 1968; La place de 1'homme dans la nature. P., 1981; The human phenomenon. M., 1987; Divine Wednesday. M., 1994. Lit. Lischer R. Marx and Teilhard. Two Ways to the New Humanity. Maryknoll (N.Y.), 1979; Pierre Teilhard de Chardin: Naissance et avenir de l'homme. P., 1987. A. V. Shabaga. Cultural studies of the twentieth century. Encyclopedia. M.1996

Great Definition

Incomplete definition ↓

- Teilhard de Chardin - Marie Joseph Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955) ☼ French anthropologist, paleontologist and cosmist theologian, who combined Christianity and Evolutionism in his teaching, the author of the theory of the noosphere (along with E. Le Roy and V. Vernadsky) (see. Dictionary of cultural studies

- Teilhard de Chardin - (Teilhard de Chardin) Pierre (May 1, 1881, Sarsena, near Clermont-Ferrand, - April 10, 1955, New York), French paleontologist, philosopher, theologian, member of the Paris Academy of Sciences (1950). He studied at the Jesuit College from 1899. Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- Teilhard de Chardin - Teilhard de Chardin Pierre (1881-1955) - French naturalist, member of the Jesuit order (1899), priest (since 1911), thinker and mystic. A descendant of Voltaire, who was the great-uncle of his mother ... The latest philosophical dictionary

- Teilhard de Chardin - Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955) - French paleontologist, philosopher and theologian. One of the discoverers of Sinanthropus. He developed the concept of "Christian evolutionism", approaching pantheism (see Noosphere). Influenced the renewal of the doctrine of Catholicism. Big encyclopedic dictionary

(Auvergne, France)

- University of Paris

- Villanova University

- Notre Dame de Mongré High School [d]

Biography

Marie Joseph Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was born on May 1, 1881 in Sarsena (Auvergne, France) into a Catholic family, the fourth of eleven children. In 1892 he entered Notre-Dame-de-Mongret College, which belonged to the Society of Jesus (Jesuit Order). In 1899, after graduating from college and receiving a bachelor's degree in philosophy and mathematics, he entered the Jesuit order.

From 1912 to 1914 he worked at the Institute of Human Paleontology at the Paris Museum of Natural History under the direction of M. Boulle (a major authority in the field of anthropology and archeology), with whom he took part in excavations in northwestern Spain.

In December 1914 he was drafted into the army, served as a porter. He went through the entire war, received the Military Medal and the Order of the Legion of Honor. It was during the war (1916) that he wrote his first essay "La vie cosmique" ("Cosmic life") - philosophical and scientific reflections on mysticism and spiritual life. Teilhard de Chardin later wrote: "la guerre a été une rencontre... avec l'Absolu" ("the war was a meeting ... with the Absolute").

On May 26, 1918, he made his eternal vows at Sainte-Foy-de-Lyon. In August 1919, while on the island of Jersey, he wrote the essay "Puissance spirituelle de la Matière" ("The Spiritual Power of Matter").

Since 1920, he continued his studies at the Sorbonne, in 1922 he defended his doctoral dissertation in the field of natural sciences (geology, botany, zoology) on the topic “Mammals of the Lower Eocene of France” and there he was appointed to the position of professor at the department of geology.

In 1923 he went on a research expedition to Tianjin (China). During the expedition, in the Ordos Desert, he wrote several articles and essays, including "La Messe sur le Monde" ("Universal Liturgy"). His article on the problem of original sin was not understood in theological circles, Teilhard de Chardin's concept was considered contrary to the teachings of the Catholic Church, and General Włodzimierz Leduchowski banned his publications and public speaking.

As a result, in April 1926, Teilhard de Chardin was again sent to work in China, where he spent a total of 20 years. Until 1932 he worked in Tianjin, then in Beijing. From 1926 to 1935, he took part in five geological expeditions in China, as a result of which he made a number of adjustments to the geological map of the country.

From 1926 to 1927 he was in eastern Mongolia and in the same years he created his first major work - a philosophical and theological essay Le Milieu divin. Essai de vie interieure" ("The Divine Environment. An Essay on the Inner Life").

In 1929, while participating in stratigraphic work at the excavations in Zhoukoudian near Beijing, Teilhard de Chardin, together with his colleagues, discovered the remains of Sinanthropus (Homo erectus). Thanks to the analysis of this find, he received wide recognition in scientific circles. Even greater glory to him and A. Breil was brought by the discovery in 1931 that Sinanthropus used primitive tools and fire.

In subsequent years, he worked as an adviser to the National Geological Department of China, took part in research expeditions (China, Central Asia, Pamir, Burma, India, Java), visited France, traveled to the USA.

In May 1946 he returned to France, resumed contacts in scientific circles, in April 1947 he took part in a conference on evolution organized by the Paris Museum of Natural History, in June he was going on an expedition to South Africa, but due to a heart attack he was forced from this refuse. In 1950, at the age of 70, Teilhard was elected to the Paris Academy of Sciences, but the ban on publications and public speaking still remained in place. In 1952, he left France and went to work in the United States, in New York, at the invitation of the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. Participated in several expeditions to South Africa. In 1954 he spent two months in France, in Auvergne, at his parents' house.

Teilhard de Chardin died in New York of a heart attack on April 10, 1955, on Easter Sunday. A year earlier, at a reception at the French consulate, he had said to his closest friends: "I would like to die on Easter, the day of the Resurrection."

After the death of Teilhard de Chardin, a commission was created, which included many of his friends, including prominent scientists (A. Breuil, J. Huxley, A. Toynbee, M. Merleau-Ponty, and others). The commission compiled and prepared for publication a ten-volume collected works, which included almost all of his works, with the exception of letters and some essays. The collected works were opened in 1957 by The Phenomenon of Man.

Views and ideas

The main works of Teilhard de Chardin in theology and philosophy are aimed at rethinking the dogmas of the Catholic Church in terms of the theory of evolution. Trying to build a new theology, the philosopher pointed out the shortcomings of the Thomistic views accepted in the Catholic Church. The first drawback he calls the static rational scheme of Thomism, which does not allow showing the dynamics of creation, the fall and redemption, which are interrelated processes. The procedural description of Christian history is necessary, according to Teilhard de Chardin, also because it is consistent with the evolutionary theory of the origin of man. The second shortcoming of Thomism is the preoccupation with the fate and salvation of the individual subject, not the collective one. While it is the salvation of the collective subject, which is an integral organism and has a single mind, that should be described by theology. The ideas of Teilhard de Chardin were criticized by representatives of his order for the departure of the primacy of theology before science, rooted in Thomism, in anti-doctrinalism and distortion of the Catholic faith, in pantheism, which is on the verge of atheism. In turn, Teilhard de Chardin considered his kind of pantheism to be natural and not contrary to Christian orthodoxy.

Noosphere

Evolution

Teilhard de Chardin distinguishes three successive, qualitatively different stages of evolution: "pre-life" (lithosphere), "life" (biosphere) and "human phenomenon" (noosphere).

The next step, in addition to the self-concentration of the noosphere, is its attachment to another thought center, a super-intellectual one, the degree of development of which no longer needs a material carrier and is entirely related to the sphere of the Spirit. Thus, matter, gradually increasing the degree of organization and self-concentration, evolves into thought, and thought, following the same path, inevitably develops into Spirit. First it will be the Spirit of the Earth. Then the concentration and catholicity of the desires of all the elements of the Spirit of the Earth will initiate the Parousia - the Second Coming of Christ, the call to Christ to move towards ["Divine Wednesday"].

Graphically, the evolutionary process can be depicted as a cone of space-time, at the base of which is multiplicity and chaos, and at the top is the highest pole of evolution, the point of the last unification into a differentiated unity, “ point Omega», « a center shining in the center of a system of centers» ["The Phenomenon of Man"]. Elements or centers (persons) are connected by the energy of love. The attributes of the Omega point are autonomy, cash, irreversibility and transcendence.

Philosophy

In his philosophical views, Teilhard de Chardin was close to monism (the unity of matter and consciousness). Rejected dualism, materialism and spiritualism. He believed that matter is the "matrix" of the spiritual principle. Physical (" tangential"") energy, which decreases according to the law of entropy, is opposite to spiritual (" radial”) is an energy that increases as evolution proceeds. Teilhard de Chardin believed that the spiritual principle is immanent in everything that exists, since it is the source of integrity and is already present in a hidden form in the molecule and atom. Consciousness acquires a psychic form in living matter. In man, the spiritual principle turns into "self-consciousness" (man " knows what he knows»).

Theology

The Omega point for Teilhard de Chardin is God and the symbolic designation of Christ, who, thanks to the power of his attraction, gives direction and purpose to the progressively evolving synthesis. The process of evolution is a natural preparation for the supernatural order indicated by Christ. Its driving force is "orthogenesis" - purposeful consciousness. When, in the course of evolution, matter-energy exhausts all its potential for further spiritual development, the convergence of the cosmic natural order and the supernatural order will lead to Parousia (“ a unique and supreme event in which the Historical will unite with the Transcendent» ["Divine Environment"]).

Thus, the basis and completion of the scientific cosmogony of Teilhard de Chardin is his theology.

Eschatology

« The end of the world is an internal return to itself of the entire noosphere, which has simultaneously reached the extreme degree of its complexity and its concentration. The end of the world is a reversal of balance, a separation of consciousness, which has finally reached perfection, from its material matrix, so that from now on it will be possible to rest with all its strength in God-Omega ”[“The Phenomenon of Man”]. This variant of the development of events is realized in the event that evil at the final stage of the Earth will be at a minimum. But it is also possible that evil, growing simultaneously with good, will reach its highest level by the end. It is then possible that the noosphere, having reached a certain point of unification, “will again be divided into two zones, respectively attracted by the two antagonistic poles of worship. To a zone of thought that has never been unified. And to the zone of all-encompassing love, reviving and… highlighting, in order to complete it, only one part of the noosphere - the one that decides to “take a step” beyond itself, into another» ["The Phenomenon of Man"].

see also

Compositions

Notes

Literature

- Bykhovsky B. E. Teilhard de Chardin// Philosophical Encyclopedic Dictionary / Ch. ed. L. F. Ilyichev , P. N. Fedoseev , S. M. Kovalev , V. G. Panov - M.: Soviet Encyclopedia, 1983. - S. 672-673. - 840 p. - 150,000 copies.

- Hildebrand D. von. Teilhard de Chardin: on the way to a new religion// New Tower of Babel. *Selected philosophical works. / Hildebrand D. von .. - St. Petersburg. , 1998.

- Grenet P., abbot. Teilhard de Chardin - Christian evolutionist. - Paris, 1961.(Russian translation - B / m, b / g (typewritten), bibl. SPbDA).

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin). Born May 1, 1881 at the Chateau Sarsena near Clermont-Ferrand, Auvergne, France - died April 10, 1955 in New York. French Catholic philosopher and theologian, biologist, geologist, paleontologist, archaeologist, anthropologist. He made significant contributions to paleontology, anthropology, philosophy, and Catholic theology. Member of the Jesuit Order (since 1899) and priest (since 1911).

One of the discoverers of Sinanthropus.

One of the creators of the theory of the noosphere (along with), created a kind of synthesis of the Catholic Christian tradition and the modern theory of cosmic evolution. He did not leave behind a school or direct students, but founded a new trend in philosophy - Teilhardism, initially condemned, but then integrated into the doctrine of the Catholic Church and becoming "the most influential theology that opposes neo-Thomism."

Marie Joseph Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was born on May 1, 1881 in Sarsena (Auvergne, France) in a Catholic family, the fourth of eleven children. In 1892 he entered Notre-Dame-de-Mongret College, which belonged to the Society of Jesus (Jesuit order).

In 1899, after graduating from college and receiving a bachelor's degree in philosophy and mathematics, he joined the Jesuit order.

From 1899 to 1901 he studied at the seminary in Aix-en-Provence, after two years of novitiate he took his first vows and in 1901-1902 he continued his philosophical and theological education at the Jesuit seminary on the island of Jersey.

From 1904 to 1907 he taught physics and chemistry at the Jesuit College of the Holy Family in Cairo. In 1908 he was sent to Hastings (England, Sussex) to study theology. On August 14, 1911, at the age of 30, he was ordained a priest.

While studying at Hastings Jesuit College, Teilhard de Chardin became friends with Charles Dawson, who "discovered" the infamous Piltdown Man.

In 1912, he even participated in excavations at the Piltdown Gravel Pit with Dawson and Arthur Woodward. Some researchers consider him involved in falsification, in particular, Louis Leakey was so sure of this that in 1971 he refused to come to a symposium organized in honor of a French priest.

From 1912 to 1914 he worked at the Institute of Human Paleontology at the Paris Museum of Natural History under the direction of M. Boulle (a major authority in the field of anthropology and archeology), with whom he took part in excavations in northwestern Spain.

In December 1914 he was drafted into the army, served as a porter. He went through the entire war, received the Military Medal and the Order of the Legion of Honor. It was during the war (1916) that he wrote his first essay "La vie cosmique" ("Cosmic life") - philosophical and scientific reflections on mysticism and spiritual life. Teilhard de Chardin later wrote: "la guerre a été une rencontre... avec l'Absolu" ("the war was a meeting... with the Absolute").

On May 26, 1918, he made his eternal vows at Sainte-Foy-de-Lyon. In August 1919, while on the island of Jersey, he wrote an essay "Puissance spirituelle de la Matière" ("The Spiritual Power of Matter").

Since 1920, he continued his studies at the Sorbonne, in 1922 he defended his doctoral dissertation at the Catholic University of Paris in the field of natural sciences (geology, botany, zoology) on the topic “Mammals of the Lower Eocene of France” and there he was appointed to the position of professor of the Department of Geology.

In 1923 he went on a research expedition to Tianjin (China). During the expedition, in the desert of Ordos, he wrote several articles and essays, including "La Messe sur le Monde" ("Universal Liturgy"). His article on the problem of original sin was not understood in theological circles, Teilhard de Chardin's concept was considered contrary to the teachings of the Catholic Church, and General Włodzimierz Leduchowski banned his publications and public speaking.

As a result, in April 1926, Teilhard de Chardin was again sent to work in China, where he spent a total of 20 years. Until 1932 he worked in Tianjin, then in Beijing.

From 1926 to 1935, Teilhard de Chardin took part in five geological expeditions in China, as a result of which he made a number of adjustments to the geological map of the country.

From 1926 to 1927 he was in eastern Mongolia and in the same years he created his first major work - the philosophical and theological essay “Le Milieu divin. Essai de vie interieure" ("The Divine Environment. An Essay on the Inner Life").

In 1929, while participating in stratigraphic work at the excavations in Zhoukoudian near Beijing, Teilhard de Chardin, together with his colleagues, discovered the remains of Sinanthropus (Homo erectus). Thanks to the analysis of this find, he received wide recognition in scientific circles. Even greater glory to him and A. Breil was brought by the discovery in 1931 that Sinanthropus used primitive tools and fire.

In subsequent years, he worked as an adviser to the National Geological Department of China, took part in research expeditions (China, Central Asia, Pamir, Burma, India, Java), visited France, traveled to the USA.

From 1938 to 1939 he worked in Paris, in the journal "Etudes" (the intellectual center of the Parisian Jesuits), he was allowed to resume the cycle of lectures and seminars. In June 1939 he returned to China.

From 1939 to 1946, during the Second World War, Teilhard de Chardin was in forced isolation in Beijing, living in the embassy quarter.

In 1940, together with Pierre Leroy, he founded the Geobiological Institute in Beijing, and in 1943, also with Leroy, he began to publish a new journal, Geobiology. During these years (1938-1940) he created his main work - "Le Phenomene humin" ("The Phenomenon of Man").

In May 1946 he returned to France, resumed contacts in scientific circles, in April 1947 he took part in a conference on evolution organized by the Paris Museum of Natural History, in June he was going on an expedition to South Africa, but due to a heart attack he was forced from this refuse.

In 1950, at the age of 70, Teilhard was elected to the Paris Academy of Sciences, but the ban on publications and public speaking still remained in place.

In 1952, he left France and went to work in the United States, in New York, at the invitation of the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research.

Participated in several expeditions to South Africa. In 1954 he spent two months in France, in Auvergne, at his parents' house.

Teilhard de Chardin died in New York of a heart attack on April 10, 1955, on Easter Sunday. A year earlier, at a reception at the French consulate, he had said to his close friends: "I would like to die on Easter, on the day of Resurrection."

After the death of Teilhard de Chardin, a commission was created, which included many of his friends, including prominent scientists (A. Breuil, J. Huxley, M. Merleau-Ponty, and others). The commission compiled and prepared for publication a ten-volume collected works, which included almost all of his works, with the exception of letters and some essays.

The collected works were opened in 1957 by The Phenomenon of Man.

Compositions by Pierre de Chardin:

La Messe sur le monde (1923)

Letters d'Egypte

Le Phénomène humain (1938-1940, published 1955)

L "Apparition de l" homme (1956)

La vision du passé (1957)

Le Milieu divin (1926-1927, published 1957)

L "Avenir de l" homme (1959)

L"Énergie humaine (1962)

L "Activation de l" energie (1963)

La Place de l "homme dans la nature (1965)

Science et Christ (1965)

Comment je crois (1969)

Les Directions de l'avenir (1973)

Écrits du temps de la guerre (1975)

Le Cœur de la matière (1976).