School Encyclopedia. Dialects in Russian

Every person who speaks Russian can easily recognize such words as, for example, "speak", "food", "blizzard", and will be able not only to define them, but also to use them in the correct form in the context. It is these words that are called public, or national vocabulary. But not everyone will be able to explain what “bayat”, “brashno”, “vyalitsa” is, only a small circle of people know such words. However, most people do not use such non-literary speech in conversation.

Dialect word: definition

It is the well-known words used in literature and in the speech of people, regardless of their place of residence and profession, that form the basis of the Russian language, all the rest of the expressions are not popular - they are used only in certain circles of the population. These include jargon, special and dialect, they are also called. Such words are divided into groups, each of which has its own sign.

Lexical groups

Certain masses of the population, carriers of non-social vocabulary, consist of a huge number of groups scattered throughout the expanses of the country and even beyond its borders. Each of them in everyday life has its own special words, and each is divided according to a certain attribute: place of residence and stratum of society. So It is those that are used in a particular area. For example, in the Pskov region there is such a thing as a north, on Baikal the same phenomenon is called barguzin, and on the Danube - belozero. The literary synonym for these words is wind.

A dialect word is part of its group by location, and words relating only to a person's occupation constitute an occupational group. But jargon refers to certain sections of society.

Where is dialect vocabulary found?

Each of the regions has its own specific words used only in this area. So, for example, in the south of the country you can find such interesting words: squares, which means bushes; kozyulya, which corresponds to the word land. In the northern cities, one can also find interesting examples of dialect speech: teplina, which means fire; lava - bridge and roe deer - plow.

Classification of dialect expressions

In literary and bookish speech, one can meet the so-called dialectisms - words that are essentially dialectal, but have their own word-formation, grammatical and phonetic features and refer to one or another dialect. Dialectisms are divided into 4 groups:

Where are dialect words used?

Examples of the use of such expressions can be found not only in conversation, but also in literary works. Although, of course, the question arises of how, and most importantly, to what extent such vocabulary can be used for artistic purposes. It is the theme of the work and the goals set by the author that determine which particular dialect word can be used in a particular case. Many factors can be taken into account here - these are aesthetic ideals, and skill, and, of course, the object being described. Indeed, sometimes, using only generally accepted speech, it is impossible to convey all the colors and character. For example, L. N. Tolstoy quite often uses dialect words to describe peasants in his works. Examples of their use in the literature can also be found in I. S. Turgenev: he used them as inclusions and quotations, which stand out quite clearly in the main text. Moreover, such inclusions in their composition have remarks that fully reveal their meaning, but without them the literary context would not have such brightness.

Dialectisms in our time

Now authors in works about villages also use dialect words, but usually do not indicate their meaning, even if these are words of a narrow application. Also, similar expressions can be found in newspaper essays, where some hero is characterized, his manner of speaking and the characteristic features of his life, determined by the area in which he lives.  Given the fact that newspaper publications should carry exclusively literary speech to the masses, the use of dialectisms should be as justified as possible. For example: "It was not in vain that I left Vasily a little away from those present." It is also worth noting that each of these uncommon words should be explained to the reader, because not a single person, when reading a book, keeps a dictionary of dialect words at hand.

Given the fact that newspaper publications should carry exclusively literary speech to the masses, the use of dialectisms should be as justified as possible. For example: "It was not in vain that I left Vasily a little away from those present." It is also worth noting that each of these uncommon words should be explained to the reader, because not a single person, when reading a book, keeps a dictionary of dialect words at hand.

Dialectisms as part of the vocabulary of the Russian language

If we talk about dictionaries, then the first mention of dialectisms can be found in the "Explanatory Dictionary of the Great Russian Language" by V. I. Dahl. In this edition, you can find 150 articles on this particular topic. Today, great attention is also paid to the study of dialectisms, because they, along with archaisms, neologisms, borrowed words and phraseological units, make up a significant part of the vocabulary of the mighty Russian language. And although most of them are not used in everyday speech and act only as a passive part, without them it would be impossible to build vivid statements or a colorful description of any object or character. That is why great writers so often resorted to dialectisms to make the text brighter. Returning to vocabulary, it should be noted that for the study of dialect words there is a whole science called dialectology.

This linguistic discipline studies the phonetic, grammatical, syntactic features of a language unit, which is geographically fixed. Also, special attention is paid here to the study of dialectisms in fiction. Linguistics shares the understanding of such words:

Summing up

Delving into the lexical structure of the Russian language, you understand how correct the phrase "great and mighty" is. After all, dialect words with their classification and structure are just a small part of a huge system for which its own science has been created. Moreover, the stock of these very words does not have constancy, it is replenished and updated. And this applies not only to dialectisms, because the number of generally accepted and commonly used words is also constantly increasing, which only emphasizes the power of the Russian language.

Dialectisms words and phraseological units are called, the use of which is characteristic of people living in a certain area.

Pskov dialectisms: Lavitsa'the outside', Sherupa'shell', perechia'contradiction', harrow‘horse in the second year’, petun'rooster', barkan'carrot', bulba'potato', good'bad', slimy'slippery', clean'sober', glare‘go around doing nothing’.

For example, PU-dialectisms of Pskov dialects: even a finger in the eye'very dark', three feet fast ', live on dry spoons ' poor ’, from all types ‘ from everywhere ', show annexation ' hit back ', lead ends ' deceive ’.

From linguistic phraseological units, losing their power of influence, gradually losing their distinctive qualities in the constancy of nationwide use, dialect phraseological units are distinguished by their unique imagery, brightness and freshness of naming realities. Wed: spinster (lit.) and Don Mykolaev (Nikolaev) girl"old maid" (the name of the time of Nicholas I, when the Cossacks left to serve for 25 years); petra girlI "spinster". Or: beat the buckets (lit.) and Don with the same meaning: beat baglai (baglai"loafer"), beat frogs, beat kayaks (kayaks"loafer"), knock down the whales (the whale"an earring near a flowering tree (birch, willow, etc.)"); Milky Way (lit.) and Don with similar semantics Batyev (Bateev, Batyev) path(named after the Tatar Khan Batu, who in his movements was guided by the Milky Way), Batyeva (Bateva, Batyeva, Batyeva, Pateyeva) road, Batyevo wheel.

Dialectisms are used mainly in the oral form of speech, since the dialect itself is mainly the oral colloquial and everyday speech of the inhabitants of the countryside.

Dialect vocabulary differs from the national one not only in a narrower scope of use, but also in a number of phonetic, grammatical and lexico-semantic features.

Depending on what features are characterized by dialectisms (as opposed to literary vocabulary), there are several types:

1) phonetic dialectisms- words that reflect the phonetic features of this dialect: barrel, vanka, tippyatok(instead of barrel, Vanka, boiling water)- South Russian dialectisms; kuricha, tsyasy, tselovek, nemchi(instead of chicken, clock, man, Germans)- dialectisms, reflecting the sound features of some northwestern dialects;

2) grammatical dialectisms- words that have grammatical characteristics other than in the literary language or differ from the common vocabulary in morphological structure. So, in southern dialects, neuter nouns are often used as feminine nouns. (the whole field, such a thing, The cat smells, whose meat it ate); forms are common in northern dialects in the cellar, in the club, in the table(instead of in the cellar, and in the club, in the table), instead of common words side, rain, run, hole etc. in dialect speech, words with the same root are used, but different in morphological structure: sboch, dozhzhok, run, nor etc.;

3) lexical dialectisms- words, both in form and in meaning, differ from the words of the national vocabulary: kochet"rooster", loin"ladle", the other day"the other day, recently", give birth"harrow", ground"manure", chatter"talk", indus"even", etc.

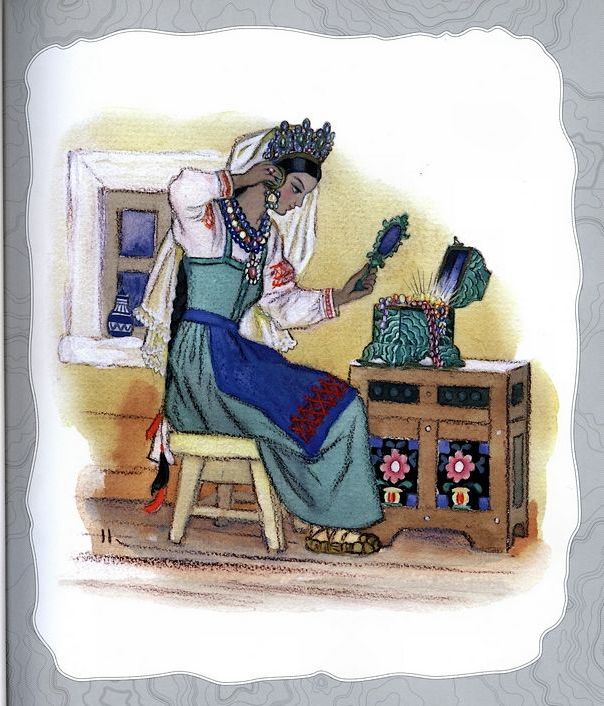

Among lexical dialectisms, local names of things and concepts common in a given area stand out. These words are called ethnographisms. For example, ethnographic is the word paneva- so in Ryazan, Tambov, Tula and some other regions they call a special kind of skirt - ‘ type of skirt made of motley homespun fabric'. In areas where floors are used as draft power, the word is common nalygach- designation of a special belt or rope tied to the horns of oxen. The pole at the well, with the help of which water is obtained, in some places is called ochep; birch bark sandals used to be called cats etc. Unlike proper lexical dialectisms, ethnographic ones, as a rule, do not have synonyms in the literary language and can only be explained descriptively.

4) Semantic dialectisms- words that have a special meaning in dialects, different from the common one. Yes, in a word top in some southern dialects they call a ravine, a verb to yawn used in the meaning of "shout, call", guess- in the meaning of "to recognize someone by sight", dark- meaning "very much" (dark love"I love you very much"); in northern dialects plow means "to sweep the floor", in Siberian wonderful means "many"; ceiling- floor, coward- hare, etc.

Ceiling'attic', mushrooms'lips', coward'rabbit', cockerel‘butter mushroom’, plow'sweep', suffer‘laugh, have fun’.

It must be remembered that dialect words are outside the literary language, so if possible, you should refrain from using local words, especially if there are literary words with the same meaning.

Some dialectisms are able to penetrate the literary language. By dialect in origin belong, for example, the words rosemary, careless, vobla, coo, length, flabby, creepy, sweetheart, strawberry, in vain, strawberry, pick, clumsy, fawn, foliage, mumble, hairy, trouble, importunate, tedious, roadside, cautious, cloudy, spider, plowman, background, fishing, wit, hill, dragonfly, taiga, smile, earflaps, eagle owl, nonsense and many others.

(gr. dialectos - adverb, dialect), have in their composition a significant number of original folk words, known only in a certain area. So, in the south of Russia, the stag is called grip, clay pot - mahotka, bench - condition etc. Dialectisms exist mainly in the oral speech of the peasant population; in an official setting, dialect speakers usually switch to a common language, the conductors of which are school, radio, television, and literature.

The original language of the Russian people was imprinted in the dialects, in certain features of the local dialects, relic forms of Old Russian speech were preserved, which are the most important source for the restoration of historical processes that once affected our language.

Dialects differ from the common national language in various features - phonetic, morphological, special word usage and completely original words unknown to the literary language. This gives grounds to group the dialectisms of the Russian language according to their common characteristics.

1. Lexical dialectisms- words known only to speakers of the dialect and outside of it, having neither phonetic nor derivational variants. For example, in South Russian dialects there are words beetroot (beetroot), tsibulya (onion), gutorit (speak), in the northern sash (belt), peplum (beautiful), golitsy (mittens). In the common language, these dialectisms have equivalents that name identical objects, concepts. The presence of such synonyms distinguishes lexical dialectisms from other types of dialect words.

2. Ethnographic dialectisms - words naming objects known only in a certain locality: shanezhki - "pies prepared in a special way", shingles - "special potato pancakes", nardek - "watermelon molasses", l / anarka - "kind of outerwear", poneva - "a kind of skirt", etc. Ethnographisms do not and cannot have synonyms in the national language, since the objects themselves, denoted by these words, have a local distribution. As a rule, these are household items, clothes, food, plants, etc.

3. Lexico-semantic dialectisms - words that have an unusual meaning in the dialect: bridge- "floor in the hut", lips - "mushrooms of all varieties, except white", shout (someone)- "call for", myself- "master, husband", etc. Such dialectisms act as homonyms for common words used with their inherent meaning in the language.

4. Phonetic dialectisms - words that have received a special phonetic design in the dialect cai(tea), chain(chain) - the consequences of "clattering" and "choking" characteristic of northern dialects; hverma(farm), paper(paper), passport(the passport), life(life).

5. Word-building dialectisms - words that have received a special affix in the dialect: stump(rooster), goose(goose), upskirt(calf), strawberry(strawberry), bro(brother), Shuryak(brother-in-law), darma(for nothing) forever(always), from where(where), pokeda(bye), Evonian(his), theirs(them), etc.

6. Morphological dialectisms - forms of inflection not characteristic of the literary language: soft endings for verbs in the 3rd person ( go, go), the ending - am nouns in the instrumental plural ( under the pillars), the ending e for personal pronouns in the genitive singular: me, you and etc.

Dialect features are also characteristic of the syntactic and phraseological levels, but they do not constitute the subject of study of the lexical system of the language.

Dialect words are not uncommon in fiction. Usually they are used by those writers who themselves come from the village, or those who are well acquainted with folk speech: A.S. Pushkin, L.N. Tolstoy, S.T. Aksakov I.S. Turgenev, N.S. Leskov, N.A. Nekrasov, I.A. Bunin, S.A. Yesenin, N.A. Klyuev, M.M. Prishvin, S.G. Pisakhov, F.A. Abramov, V.P. Astafiev, A.I. Solzhenitsyn, V.I. Belov, E.I. Nosov, B.A. Mozhaev, V.G. Rasputin and many others.

A dialect word, phrase, construction included in a work of art to convey local color when describing village life, to create a speech characteristic of characters, is called dialectism.

More A.M. Gorky said: "In every province and even in many districts we have our own dialects, our own words, but a writer must write in Russian, and not in Vyatka, not in balakhonsky."

No need to understand these words of A.M. Gorky as a complete ban on the use of dialect words and expressions in a literary work. However, you need to know how and when you can and should use dialectisms. At one time, A.S. Pushkin wrote: "True taste does not consist in the unconscious rejection of such and such a word, such and such a turn, but in a sense of proportionality and conformity."

In "Notes of a hunter" I.S. Turgenev, you can find quite a lot of dialectisms, but no one will object to the fact that this book is written in excellent Russian literary language. This is primarily due to the fact that Turgenev did not oversaturate the book with dialectisms, but introduced them prudently and cautiously. For the most part, dialectisms are used by him in the speech of characters, and only occasionally does he introduce them into descriptions. At the same time, using an obscure dialect word, Turgenev always explains it. So, for example, in the story "Biryuk" I.S. Turgenev, after the phrase: “My name is Thomas,” he answered, “and nicknamed Biryuk,” he makes a note: “In the Oryol province, a lonely and gloomy person is called Biryuk.” In the same way, he explains the dialectal meaning of the word "top": "Horseback" is called a ravine in the Oryol province.

Turgenev replaces in the author's speech a number of dialect words with literary words that have the same meaning: instead of a stump in the meaning of "trunk", the writer introduces a literary trunk, instead of a plant ("breed") - breed, instead of separate ("push apart") - push apart. But in the mouths of the characters there are such words as fershel (instead of "paramedic"), a songwriter, and so on. However, even in the author's speech, all dialectisms are not eliminated. Turgenev retains those that designate objects that have not received an exact name in the literary language (kokoshnik, kichka, paneva, amshannik, greenery, etc.). Moreover, sometimes in later editions he even introduces new dialectisms into the author's speech, trying to increase the figurativeness of the narrative. For example, he replaces the literary "mumbled ... voice" with the dialectal "mumbled ... voice", and this gives the old man's speech a clearly visible, felt character.

How masterfully used dialect words and expressions L.N. Tolstoy to create Akim's speech characteristics in the drama "The Power of Darkness".

In the 50-60s of the XIX century. widely used dialectisms in the works of art by I.S. Nikitin. In his poems, he used dialect vocabulary mainly to reflect the local living conditions and life of the people he wrote about. This circumstance led to the presence among dialect words of most nouns denoting individual objects, phenomena and concepts. Such, for example, according to the study of S.A. Kudryashov, names of household items: gorenka, konik (shop), gamanok (purse), such concepts as izvolok (elevation), adversity (bad weather), buzz (buzz). It can be seen that these dialect words are mainly belonging to the South Great Russian dialect, in particular the Voronezh dialects.

In the works of D.N. Mamin-Sibiryak, belonging to the 80-90s of the XIX century, the dialect vocabulary of the Urals has found its wide reflection. In them, according to the study of V.N. Muravyova, dialectisms are used in the speech of the characters and in the language of the author's narration to create a kind of local color, realistic display of the life of the Ural population, descriptions of agricultural work, hunting, etc. In the speech of the characters, dialectisms are also a means of speech characterization. You can name some of these dialectisms used in the stories of Mamin-Sibiryak: a plot is a fence, an oak is a type of sundress, a stand is a barn for cattle, feet are shoes, a stomach is a house (as well as an animal), battle is torment.

Perfectly used the dialect vocabulary of the Urals P.P. Bazhov. In his tales "Malachite Box" researchers, such as A.I. Chizhik-Poleiko noted about 1200 dialect words and expressions. All of them perform certain functions in the work: or designate specific objects (povet - a room under a canopy in a peasant yard); or they characterize the narrator as a representative of the local dialect (in these cases, from the synonyms of the literary language and dialectisms, Bazhov chooses dialect words: log - ravine, zaplot - fence, pimy - felt boots, midges - mosquitoes, juice - slag); or introduced to describe the phenomena of the past (kerzhak - Old Believer); or reflect local detail in the designation of some objects (urema - small forest), etc.

In Soviet literature, all researchers noted the brilliant use of dialectal features of the Don language by M.A. Sholokhov. The speech of the heroes of "The Quiet Flows the Don" and "Virgin Soil Upturned" is extremely colorful and colorful precisely because it is saturated with dialectisms to the right extent. The published chapters from the second book of "Virgin Soil Upturned" once again testify to the skill of M.A. Sholokhov as an artist of the word. It is important for us to note now that in these chapters M.A. Sholokhov introduced a fairly significant number of dialect words and forms that give the speech of the characters a peculiar local flavor. Among the dialectal features noted here, one can also find words unknown in the literary language (provesna - the time before the beginning of spring, cleanup - pasture for livestock, arzhanets - a cereal plant similar to rye, cut - hit, lyta - run away, ogina - carry out time, at once - immediately, etc.), and especially often - dialect formation of separate forms of various words (nominative, genitive and accusative plural: blood; raise orphans; did not give out killers; without nit-picking; there were no napkins; there is no evidence; verbal forms: crawling instead of "crawling", moaning instead of "groaning", dragging instead of "dragling", ran instead of "ran", lie down instead of "lie down", get off instead of "get off"; adverbs on foot and top instead of "on foot", "on horseback" etc.), and a reflection of the dialectal pronunciation of individual words (vyunosha - "young man", protchuyu - "other", native, etc.).

In the story “The Pantry of the Sun”, M. Prishvin repeatedly uses the dialect word elan: “Meanwhile, it was precisely here, in this clearing, that the interlacing of plants stopped altogether, there was elan, the same as an ice hole in the pond in winter. In an ordinary elani, at least a little bit of water is always visible, covered with large, white, beautiful kupava, water lilies. That is why this spruce was called Blind, because it was impossible to recognize it by its appearance. Not only does the meaning of the dialect word become clear to us from the text, the author, at the first mention of it, gives a footnote-explanation: "Elan is a swampy place in a swamp, it's like a hole in the ice."

Thus, dialectisms in the works of art of Soviet literature, as well as in the literature of the past, are used for various purposes, but they always remain only an auxiliary means for fulfilling the tasks assigned to the writer. They should only be introduced in contexts where they are needed; in this case, dialectisms are an important element of artistic depiction.

However, even in our time, words and forms taken from dialects sometimes penetrate into literary works, the introduction of which into the fabric of artistic narrative does not seem legitimate.

A. Surkov in the poem "Motherland" uses the participial form of the verb to yell (plow): "Not wounded by grandfather's plows", - this is justified by the poet's desire to recreate the distant past of the Russian land in the reader's mind and by the fact that such a use of a word formed from a dialect verb, gives the whole line a solemn character, corresponding to the whole character of the poem. But when A. Perventsev in the novel "Matrosy" uses in the author's speech the form of the 3rd person singular of the present tense from the verb "sway" - sways instead of the literary sway, then such an introduction of dialectism is not justified in any way and can only be considered an unnecessary clogging of the literary language.

In order for the word to become clear, no boring explanations or footnotes are needed at all. It's just that this word should be put in such a connection with all neighboring words so that its meaning is clear to the reader immediately, without the author's or editorial remarks. One incomprehensible word can destroy for the reader the most exemplary construction of prose.

It would be absurd to argue that literature exists and acts only as long as it is understood. Incomprehensible deliberately abstruse literature is needed only by its author, but not by the people.

The clearer the air, the brighter the sunlight. The more transparent the prose, the more perfect its beauty and the stronger it resonates in the human heart. Leo Tolstoy expressed this thought briefly and clearly:

"Simplicity is a necessary condition for beauty."

In his essay Dictionaries, Paustovsky writes:

“Of the many local words spoken, for example, in Vladimirskaya

and Ryazan regions, some, of course, is incomprehensible. But there are words that are excellent in their expressiveness. For example, the old word "okoeom" that still exists in these areas is the horizon.

On the high bank of the Oka, from where a wide horizon opens, there is the village of Okoyomovo. From Okoemovo, as the locals say, you can see half of Russia. The horizon is everything that our eye can grasp on earth, or, in the old way, everything that “the eye can see”. Hence the origin of the word "okoe". The word "Stozhary" is also very harmonious - this is how people call star clusters in these areas. This word consonantly evokes the idea of a cold heavenly fire.

There are two types of dialects in the Russian language: social and territorial.

Social dialects (jargon) include dialect words that are used by a particular social group. Hence the name of the species. Social dialects are characterized by lexical language features. In the case of a social group, one should not confuse dialects with professional words.

The territorial dialect includes words that are used in the speech of people in a certain area. They are characterized by phonetic, grammatical, lexical, syntactic features.

Dialect classification

In the last century, dialectological maps of the Russian language were compiled, monographs of dialect division were published. They contain material on adverbs, dialects, groups of dialects. The information below is based on the 1964 classification.

There are three dialects in the Russian language (two dialects and one dialect): the North Russian dialect, the South Russian dialect, and the Central Russian dialect. For example, the literary word "speak" has an analogue "bait" in the Central Russian dialect and "gut" in the South Russian. There are also smaller divisions. Well-known examples: Muscovites - “akayut”, villagers - “okayut”, differences in the speech of Muscovites and Petersburgers.

northern dialect

Groups of dialects of the Northern Russian dialect:

- Ladoga-Tikhvin group

- Vologda group

- Kostroma group

- Interzonal dialects

- Onega group

- Lach dialects

- Belozersko-Bezhetsky dialects

Southern dialect

Groups of dialects of the South Russian dialect:

- Western group

- Upper Dnieper group

- Upper Desninskaya group

- Kursk-Oryol group

- Eastern (Ryazan) group

- Type A interzonal dialects

- Interzonal dialects of type B

- Tula group

- Yelets dialects

- Oskol dialects

Central Russian dialect

The Central Russian dialect is specific for the Pskov, Tver, Moscow, Vladimir, Ivanovo, Nizhny Novgorod regions.

- Western Central Russian dialects

- Western Central Russian bordering dialects

- Gdovskaya group

- Novgorod dialects

- Western Central Russian Akaya dialects

- Pskov group

- Seligero-Torzhkov dialects

- Western Central Russian bordering dialects

- Eastern Central Russian dialects

- Eastern Central Russian bordering dialects

- Vladimir-Volga group

- Tver subgroup

- Nizhny Novgorod subgroup

- Vladimir-Volga group

- Eastern Central Russian Akaya dialects

- Department A

- Department B

- Department B

- Dialects of Chukhlomsky Island

- Eastern Central Russian bordering dialects

Linguistic characteristic

The linguistic characteristics of dialects include phonetics, vocalism, syntax. The northern and southern dialects have their own dialectal features. Central Russian dialects combine certain features of the northern and southern dialects.

The phonetics of Russian dialects shows the difference between adverbs in the pronunciation of consonants (long consonant), fricative sound, softening of consonants, yakane, etc. In the dialects of the Russian language, five-form, six-form and seven-form systems of vocalism and “okane”, “akanie” are distinguished as types of unstressed vocalism . The difference in the syntax of dialects is associated with the use of different cases in the construction of phrases, different combinations of prepositions with nouns, and the use of different forms of the verb. The difference can be traced in the construction of simple sentences: changing the order of words, using particles, etc.