The works of Theophanes the Greek have survived to this day. School encyclopedia

In the photo: Surviving fragments of Theophanes' paintings in the altar of the Church of the Savior on Ilyin Street in Novgorod.

The paintings of the Spasskaya Church are the only “documented” work Feofan the Greek. It is known that he “signed” more than forty churches, created many icons, and also worked in the field of book miniatures. But his frescoes have not been preserved anywhere except Novgorod, the books decorated by him have all been lost, and cautious art historians prefer to speak of the icons as belonging to the brush of the “master of Theophan’s circle.”

The surviving facts of the biography of Theophanes the Greek are as scarce as the grains of his heritage. We know that he was born somewhere in Byzantium (hence the nickname - Greek) around 1340. Before coming to Rus' (we’ll talk about the circumstances under which this happened a little later), he managed to work in Constantinople, Chalcedon, Galata and Cafe (modern Feodosia). We draw this information from a letter from the hagiographer and scribe Epiphanius the Wise, addressed to the Archimandrite of the Tver Afanasyev Monastery Kirill - in essence, the only source that reveals to us at least some details of Theophan’s life. It is quite possible that the artist also visited Mount Athos, where he learned the hesychast teaching about the uncreated light, which had such a decisive impact on his work.

Theophanes the Greek - Metropolitan Cyprian's man

The generally accepted version says that Theophanes the Greek arrived in Rus' either at the invitation of Metropolitan Cyprian, or even in his retinue. We do not have the opportunity to dwell in detail on the figure of this figure; we will only say that his role is as important in the history of the Russian Church as it is ambiguous.

Cyprian appeared in Rus' as the “personal representative” of Patriarch Philotheus of Constantinople in 1373 and was, as it were, “appointed” by him in advance to be the metropolitan of Moscow - although Metropolitan Alexy, who occupied the holy throne, was still in good health. Church historian A.V. Kartashev comments on this situation as follows:

“How he (Cyprian) ended up at the see of the Russian metropolitanate under a living metropolitan can already be explained by his personal diplomatic abilities and the overly flexible moral behavior of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.”

At first, circumstances were unfavorable for Cyprian. Even after the death of Metropolitan Alexy (in 1378), Muscovites were not ready to consider the Greek (that is, actually, Serb by origin) Cyprian as a tolerable candidate for the metropolitan see. And, accordingly, they didn’t want to see “his people” in Moscow either.

Perhaps this is why Theophanes the Greek was in Novgorod in the late 1370s. Being the second most important cathedral city after Moscow (if we talk about North-Eastern Rus'), Novgorod was also an important political center. And Cyprian could not help but want to strengthen his influence here - since he could not yet “reach” Moscow.

In the description of Epiphanius the Wise, Theophan the Greek appears as “an elegant icon painter” and “a glorious wise man, a cunning philosopher.” That is, not only as an artist, but also as a theologian. And there is reason to believe that Theophanes’ painting itself had programmatic significance in the context of the controversy between Cyprian and his opponents. After all, monumental art in that era had a colossal influence on minds - replacing all current media combined.

Works of Theophanes the Greek

What happened in the life of Theophan the Greek in the 1380s and where he was “grafted” - alas, we cannot say. Perhaps, having completed the paintings in the Spasskaya Church of Novgorod in 1378, the master remained here for some time. Some researchers “send” him for these few years to Nizhny Novgorod, Serpukhov and Kolomna (based partly on the letter of Epiphanius the Wise mentioned by us and other indirect sources). Be that as it may, in the early 1390s, Theophanes arrived in Moscow and began vigorous activity here.

In Epiphanius we read:

“In Moscow, three churches are signed (by Theophan): the Annunciation of the Holy Mother of God, St. Michael, and one in Moscow (meaning, obviously, the Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, built on the orders of Grand Duchess Evdokia). In Saint Michael (in the Archangel Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin) on the wall of the city of Prince Vladimir Andreevich, Moscow itself was also written in a stone wall; The Great Prince's mansion has an unknown signature and is strangely signed; and in the stone church of the Holy Annunciation the root of Jesse and the Apokolipsus are also written on.”

Miniature from the Facial Chronicle, illustrating the work of Feofan in the Archangel Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin.

Miniature from the Facial Chronicle, illustrating the work of Feofan in the Archangel Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin.

None of these creations survived.

Of course, the message about the paintings performed by Feofan in the mansion of the “Great Prince” is of interest. I wonder what subjects the artist considered it possible to turn to when working for a “worldly” customer? An assumption is often made - in our opinion, plausible - that there could be allegories that the Muscovites of that era had not yet seen, which is why Epiphanius calls the “signature” of the Grand Duke’s mansion “unknown” and “strangely sculpted,” that is, “extraordinary.” This consideration is supported by the fact that in his “pre-Russian” period, Theophanes worked in Galata, the Genoese suburb of Constantinople, and the Cafe, which was also then owned by Genoa. Allegorical paintings were already widespread there.

Painting of the Annunciation Church in the Kremlin - the last work of Theophanes the Greek in Moscow

“Transfiguration of the Lord” (c. 1403) from the collection of the Tretyakov Gallery. Not only the style, but also the plot, fundamental in the teaching of Gregory Palamas about the uncreated light, makes us suspect that this icon was painted by Theophanes the Greek. On Mount Tabor, as the theologian says, the apostles saw the uncreated glory of the Divine - “the super-reasonable and unapproachable light itself, the heavenly light, immense, transtemporal, eternal, light shining with incorruptibility.” And this light can be seen by those who have achieved salvation through the unceasing Jesus Prayer.

“Transfiguration of the Lord” (c. 1403) from the collection of the Tretyakov Gallery. Not only the style, but also the plot, fundamental in the teaching of Gregory Palamas about the uncreated light, makes us suspect that this icon was painted by Theophanes the Greek. On Mount Tabor, as the theologian says, the apostles saw the uncreated glory of the Divine - “the super-reasonable and unapproachable light itself, the heavenly light, immense, transtemporal, eternal, light shining with incorruptibility.” And this light can be seen by those who have achieved salvation through the unceasing Jesus Prayer.

Feofan Epiphanius calls the painting of the Annunciation Church in the Kremlin the last Moscow work. The master worked on it together with Elder Prokhor from Gorodets and. Moreover, of course, Feofan in this case was the head of the “artel”. His name comes first in the corresponding chronicle entry. In the Annunciation Church, as we remember, Theophanes wrote the compositions “Apocalypse” and “The Root of Jesse” (a subject that had not previously been found in Russian icon painting, and subsequently was not very “popular”). The paintings created in 1405 did not decorate the Annunciation Church for long: in 1416 it was completely rebuilt, and in 1485-1489 the current Annunciation Cathedral was erected. But the memory of Theophanes’ frescoes did not disappear. In the middle of the 16th century, “Apocalypse” and “Root of Jesse” again “appeared” on the walls of the cathedral - as a tribute to the great master.

There is also a tradition of attributing to Theophanes the icons of the deisis order from the iconostasis of the Annunciation Cathedral. In any case, in terms of timing and the highest level of performance, they are quite “suitable” for our hero.

Master's handwriting

Feofan’s work style was strikingly different from the usual “norms” of that time. We have already briefly talked about the originality of his brushstroke and color, about the amazing “gaps”, but now let’s look into his workshop - fortunately, through the efforts of Epiphanius the Wise, we have such an opportunity.

Epiphanius wrote - with reverent surprise - about Theophanes' method (we give the text in a modern retelling):

“When he painted or painted, no one ever saw him looking at the samples, as some of our icon painters do, looking back and forth in bewilderment, so they no longer paint, but look at the samples. He seemed to write with his hands and constantly move from place to place with his feet; He talked with his tongue with those who came, and with his mind he pondered the lofty and wise... So I, unworthy,” adds Epiphanius humbly, “often went to talk to him, for I always loved to talk with him.”

It is unclear how long Epiphanius’s “interviews” with Feofan lasted. The Russian scribe says nothing about the circumstances of the death (or departure?) of the icon painter. It is generally accepted that Theophanes died around 1410. But where did he meet his death? Is it in Moscow? Or perhaps he wanted to return to Constantinople? It is only obvious that in the first half of the 1410s, when Epiphanius composed his message to Archimandrite Kirill, Theophan was no longer in Moscow.

Theophanes the Greek is as mysterious as it is.

We know about the extraordinary personality of Theophanes the Greek (Grechanin) thanks to two historical figures and their good relationships. This is Kirill, archimandrite of the Tver Spaso-Afanasyevsky Monastery, and hieromonk of the Trinity-Sergius Monastery, follower of Sergius of Radonezh, and later the compiler of his lives Epiphanius the Wise.

In 1408, due to the raid of Khan Edigei, Hieromonk Epiphanius grabbed his books and fled from danger from Moscow to neighboring Tver, and there he took refuge in the Spaso-Afanasyevsky Monastery and became friends with its rector, Archimandrite Kirill.

It was probably during that period that the abbot saw the “Church of Sofia of Constantinople”, depicted in the Gospel that belonged to Epiphanius. A few years later, in a letter that has not survived, Cyril apparently asked about the drawings with views of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, which impressed him and was remembered. Epiphanius responded by giving a detailed explanation of their origin. A copy of the 17th–18th centuries has survived. an excerpt from this response letter (1413 - 1415), entitled: “Copied from the letter of Hieromonk Epiphanius, who wrote to a certain friend of his Cyril.”

Epiphanius in his message explains to the abbot that he personally copied those images from the Greek theophan Feofan. And then Epiphanius the Wise talks in detail and picturesquely about the Greek icon painter. Therefore, we know that Theophanes the Greek worked “from his imagination,” i.e. did not look at canonical samples, but wrote independently at his own discretion. Feofan was in constant motion, as he moved away from the wall, looked at the image, checking it with the image that had formed in his head, and continued to write. Such artistic freedom was unusual for Russian icon painters of that time. During his work, Feofan willingly maintained a conversation with those around him, which did not distract him from his thoughts and did not interfere with his work. Epiphanius the Wise, who knew the Byzantine personally and communicated with him, emphasized the master’s intelligence and talent: “he is a living husband, a glorious wise man, a very cunning philosopher, Theophanes, a Grechin, a skilled book illustrator and an elegant icon painter.”

There is no information about the family, nor about where and how Feofan received his education in icon painting. In the message, Epiphanius points only to the finished works of the Byzantine. Theophanes the Greek decorated with his paintings forty churches in various places: Constantinople, Chalcedon and Galata (suburbs of Constantinople), Cafe (modern Feodosia), in Novgorod the Great and Nizhny, as well as three churches in Moscow and several secular buildings.

After work in Moscow, the name of Theophanes the Greek is not mentioned. Details of his personal life are not known. The date of death is not exact. There is an assumption, based on indirect signs, that in his old age he retired to the holy Mount Athos and ended his earthly life as a monk.

Theophanes the Greek in Veliky Novgorod

The only reliable works of the Russian-Byzantine master are considered to be only the paintings in Novgorod the Great, where he lived and worked for some time. Thus, in the Novgorod Chronicle of 1378 it is specifically stated that “the church of our Lord Jesus Christ” was painted by the Greek master Theophan. We are talking about the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyin Street, built in 1374 on the Trade side of the city. The Byzantine master was apparently called by the local boyar Vasily Mashkov to paint the temple. Presumably, Theophanes arrived in Rus' with Metropolitan Cyprian.

The Church of the Transfiguration survived, but the Greek paintings were only partially preserved. They were cleared intermittently for several decades, starting in 1910. The frescoes, although they have come down to us with losses, give an idea of Theophanes the Greek as an outstanding artist who brought new ideas to Russian icon painting. The painter and art critic Igor Grabar assessed the visit to Russia of masters of the magnitude of Theophanes the Greek as a fruitful external impulse at turning points in Russian art, when it was especially needed. Theophanes the Greek found himself in Rus' when the state was liberated from the invasion of the Tatar-Mongols, slowly rose and was revived.

Feofan the Greek in Moscow

Moscow chronicles indicate that Theophanes the Greek created murals of Kremlin churches in the late 14th - early 15th centuries:

- 1395 - painting of the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary in the vestibule in collaboration with Simeon the Black.

- 1399 - painting.

- 1405 - painting of what previously stood on the current site. Feofan painted the Annunciation Cathedral together with the Russian masters Prokhor from Gorodets and Andrei Rublev.

Miniature of the Front Chronicle, 16th century. Feofan the Greek and Semyon Cherny painting the Church of the Nativity. Caption: “In the same year, in the center of Moscow, the Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the chapel of St. Lazarus were painted. And the masters are Theodore the Greek and Semyon Cherny.”

Features of the work of Theophanes the Greek

The frescoes of Theophanes the Greek are characterized by minimalism in color scheme and lack of elaboration of small details. That is why the faces of the saints appear stern, focused on internal spiritual energy and radiate powerful force. The artist placed the spots of white in such a way that they create light similar to Favor’s and focus attention on important details. His brush strokes are characterized by sharpness, precision and boldness of application. The characters in the icon painter’s paintings are ascetic, self-sufficient and deep in silent prayer.

The work of Theophanes the Greek is associated with hesychasm, which implied unceasing “smart” prayer, silence, purity of heart, the transforming power of God, the Kingdom of God within man. Centuries later, following Epiphanius the Wise, Theophan the Greek was recognized not only as a brilliant icon painter, but as a thinker and philosopher.

Works of Theophanes the Greek

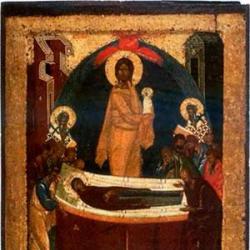

There is no reliable data, but the work of Theophanes the Greek is usually attributed to the double-sided icon of the “Don Mother of God” with the “Assumption of the Mother of God” on the reverse and the Deesis tier of the iconostasis of the Annunciation Cathedral of the Kremlin. The iconostasis of the Annunciation Cathedral is also distinguished by the fact that it became the first in Rus', on the icons of which the figures of saints are depicted in full height.

Previously it was assumed that the icon “Transfiguration of the Lord” from the Transfiguration Cathedral of Pereslavl-Zalessky belongs to the brush of Theophanes the Greek and the icon painters of the workshop he created in Moscow. But recently doubts about its authorship have intensified.

Don Icon of the Mother of God. Attributed to Theophanes the Greek.

Don Icon of the Mother of God. Attributed to Theophanes the Greek.

Icon "Transfiguration of Jesus Christ before the disciples on Mount Tabor." ? Theophanes the Greek and his workshop. ?

Icon "Transfiguration of Jesus Christ before the disciples on Mount Tabor." ? Theophanes the Greek and his workshop. ?

Theophanes the Greek. Jesus Pantocrator- R inventory in the dome of the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyin Street. Velikiy Novgorod.

Theophanes the Greek. Jesus Pantocrator- R inventory in the dome of the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyin Street. Velikiy Novgorod.

Theophanes the Greek. Seraphim- f fragment of a painting in the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyin Street. Velikiy Novgorod.

Theophanes the Greek. Seraphim- f fragment of a painting in the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyin Street. Velikiy Novgorod.

Theophanes the Greek. Daniil Stylite- fragment of a painting in the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyin Street. Velikiy Novgorod.

Theophanes the Greek. Daniil Stylite- fragment of a painting in the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyin Street. Velikiy Novgorod.

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru/

St. Petersburg Humanitarian University of Trade Unions

KIROVSKYBRANCH

TEST

Bydisciplinestoryarts

TOPIC: The work of Theophanes the Greek

Introduction

1. Biography of the creator

2. The work of Theophanes the Greek

2.1 Iconography

Conclusion

Bibliography

Introduction

Theophanes the Greek is one of the few Byzantine icon painters whose name remains in history, perhaps due to the fact that, being in the prime of his creative powers, he left his homeland and worked in Rus' until his death, where they knew how to appreciate the individuality of the painter. This brilliant “Byzantine” or “Grechin” was destined to play a decisive role in the awakening of the Russian artistic genius.

Brought up on strict canons, he already in his youth surpassed them in many ways. His art turned out to be the last flower on the dry soil of Byzantine culture. If he had remained to work in Constantinople, he would have turned into one of the faceless Byzantine icon painters, whose work emanates coldness and boredom. But he didn't stay. The further he moved from the capital, the wider his horizons became, the more independent his convictions.

In Galata (a Genoese colony) he came into contact with Western culture. He saw her palazzo and churches, observed free Western morals, unusual for a Byzantine. The businesslike nature of the inhabitants of Galata was sharply different from the way of Byzantine society, which was in no hurry, lived in the old fashioned way, and was mired in theological disputes. He could have emigrated to Italy, as many of his talented fellow tribesmen did. But, apparently, it was not possible to part with the Orthodox faith. He directed his feet not to the west, but to the east.

Feofan the Greek came to Rus' as a mature, established master. Thanks to him, Russian painters had the opportunity to get acquainted with Byzantine art performed not by an ordinary master craftsman, but by a genius.

His creative mission began in the 1370s in Novgorod, where he painted the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyin Street (1378). Prince Dmitry Donskoy lured him to Moscow. Here Theophanes supervised the paintings of the Annunciation Cathedral in the Kremlin (1405). He painted a number of remarkable icons, among which (presumably) the famous Our Lady of the Don, which became the national shrine of Russia (Initially, the “Our Lady of the Don” was located in the Assumption Cathedral in the city of Kolomna, erected in memory of the victory of the Russian army on the Kulikovo field. Ivan the Terrible prayed before her as he set off on a trip to Kazan).

The Russians were amazed by his deep intelligence and education, which earned him fame as a sage and philosopher. “A glorious sage, a very cunning philosopher... and among painters - the first painter,” Epiphanius wrote about him. It was also striking that while working, he never consulted the samples (“copybooks”). Feofan gave the Russians an example of extraordinary creative daring. He created at ease, freely, without looking at the originals. He wrote not in monastic solitude, but in public, as a brilliant improvising artist. He gathered crowds of admirers around him, who looked with admiration at his cursive writing. At the same time, he entertained the audience with intricate stories about the wonders of Constantinople. This is how the new ideal of the artist was defined in the minds of the Russians - the isographer, the creator of new canons.

The purpose of the test is to examine the work of Theophan the Greek

Tasks:

· Find out the biography of Theophanes the Greek

· Consider the work of Theophan the Greek

· Consider the iconography of Theophanes the Greek

1. Biography of Theophanes the Greek

Theophamnes the Greek (about 1340 - about 1410) was a great Russian and Byzantine icon painter, miniaturist and master of monumental fresco paintings.

Theophanes was born in Byzantium (hence the nickname Greek), before coming to Rus' he worked in Constantinople, Chalcedon (a suburb of Constantinople), Genoese Galata and Cafe (now Feodosia in Crimea) (the paintings have not survived). He probably arrived in Rus' together with Metropolitan Cyprian.

Theophanes the Greek settled in Novgorod in 1370. In 1378, he began work on the painting of the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyin Street. The most grandiose image in the temple is the chest-to-chest image of the Savior Almighty in the dome. In addition to the dome, Theophan painted the drum with the figures of the forefathers and prophets Elijah and John the Baptist. The paintings of the apse have also reached us - fragments of the order of the saints and the “Eucharist”, part of the figure of the Virgin Mary on the southern altar column, and “Baptism”, “Nativity of Christ”, “Candlemas”, “Christ’s Sermon to the Apostles” and “Descent into Hell” on the vaults and adjacent walls. The frescoes of the Trinity chapel are best preserved. This is an ornament, frontal figures of saints, a half-figure of the “Sign” with forthcoming angels, a throne with four saints approaching it and, in the upper part of the wall - Stylites, the Old Testament “Trinity”, medallions with John Climacus, Agathon, Acacius and the figure of Macarius of Egypt.

Theophanes the Greek left a significant contribution to Novgorod art, in particular, the masters who professed a similar worldview and partly adopted the master’s style were the masters who painted the churches of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary on Volotovo Field and Theodore Stratilates on the Stream. The painting in these churches is reminiscent of the frescoes of the Church of the Savior on Ilyin in its free manner, the principle of constructing compositions and the choice of colors for painting. The memory of Theophanes the Greek remained in Novgorod icons - in the icon “Fatherland” (14th century) there are seraphim copied from the frescoes of the Church of the Savior on Ilyin, in the stamp “Trinity” from a four-part icon of the 15th century there are parallels with Theophanes’ “Trinity”, and also in several other works. Theophan’s influence is also visible in Novgorod book graphics, in the design of such manuscripts as “The Psalter of Ivan the Terrible” (last decade of the 14th century) and “Pogodinsky Prologue” (second half of the 14th century).

2. The work of Theophanes the Greek

Theophanes the Greek was one of the Byzantine masters. Before arriving in Novgorod, the artist painted over 40 stone churches. He worked in Constantinople, Chalcedon, Galata, Caffa. Possessing enormous artistic talent, Feofan painted figures with broad strokes. He applied rich white, bluish-gray and red highlights on top of the initial padding. Leakey painted over a dark brown pad, highlighting the shadow parts and darkening the illuminated parts. Modeling faces, Feofan finishes the letter by applying white highlights, sometimes in the shadowed parts of the face. Many researchers believe that Theophanes’s work is associated with the Palaiologan Renaissance, including the doctrine of hesychia.

Theophan the Greek's first works in Rus' were completed in Novgorod. These are frescoes of the Cathedral of the Transfiguration on Ilinaya Street, including a chest-to-chest image of the Savior Pantocrator in the central dome. The frescoes of the northwestern part of the temple are best preserved. The main thing in the painting is the exaltation of the ascetic feat, the expectation of the apocalypse. In Feofan’s coloring, dark tones acquired a special sonority; the artist modeled the form with bright strokes of whitening tones - spaces. The Greek later worked in Nizhny Novgorod, participating in the creation of iconostases and frescoes in the Spassky Cathedral, which have not survived to this day. Theophanes the Greek was first mentioned in Moscow in 1395. The production of the double-sided icon “Our Lady of the Don” is associated with Theophan’s workshop, on the reverse side of which the “Assumption of the Virgin Mary” is depicted. The image of Mary is given in dark warm colors, the forms are carefully worked out. In the fresco “The Dormition of the Mother of God” Theophan reduced the number of characters, on a dark blue background - Christ dressed in a golden tunic, the Mother of God reclining on his deathbed. In the Transfiguration Cathedral of Pereyaslavl-Zalessky, Feofan painted the Church of the Archangel Michael in 1399, and in 1405 - the Annunciation Cathedral together with Andrei Rublev. The iconostasis of the Annunciation is the oldest Russian iconostasis that has survived to this day.

2.1 Iconography of Theophanes the Greek

Icon painting appeared in Rus' in the 10th century, after in 988 Rus' adopted a new religion from Byzantium - Christianity. By this time, in Byzantium itself, icon painting had finally turned into a strictly legalized, recognized canonical system of images. Worship of the icon has become an integral part of Christian doctrine and worship. Thus, Rus' received the icon as one of the “foundations” of the new religion.

N: Symbolism of temples: 4 walls of the temple, united by one chapter - 4 cardinal directions under the authority of a single universal church; the altar in all churches was placed in the east: according to the Bible, in the east was the heavenly land - Eden; According to the Gospel, the ascension of Christ took place in the east. And so on, so, in general, the system of paintings of the Christian church was a strictly thought-out whole.

The extreme expression of freethinking in Rus' in the 14th century. The Strigolnik heresy began in Novgorod and Pskov: they taught that religion is everyone’s internal affair and every person has the right to be a teacher of faith; they denied the church, spiritually, church rites and sacraments, they called on the people not to confess to the priests, but to repent of the sins of the “damp mother earth.” The art of Novgorod and Pskov in the 14th century as a whole clearly reflects the growing free-thinking. Artists strive for images that are more vibrant and dynamic than before. Interest in dramatic plots arises, interest in the inner world of a person awakens. The artistic quest of the 14th century masters explains why Novgorod could become the place of activity of one of the most rebellious artists of the Middle Ages - the Byzantine Theophanes the Greek.

Feofan came to Novgorod, obviously, in the 70s of the 14th century. Before that, he worked in Constantinople and cities nearby the capital, then moved to Kaffa, from where he was probably invited to Novgorod. In 1378, Theophanes performed his first work in Novgorod - he painted the Church of the Transfiguration with frescoes.

It is enough to compare Elder Melchizedek from this church with Jonah from the Skovorodsky Monastery to understand what a stunning impression Theophan’s art must have made on his Russian contemporaries. Feofan’s characters not only look different from each other, they live and express themselves in different ways. Each character of Feofan is an unforgettable human image. Through movements, posture, and gesture, the artist knows how to make the “inner man” visible. The gray-bearded Melchizedek, with a majestic movement worthy of a descendant of the Hellenes, holds the scroll with the prophecy. There is no Christian humility and piety in his posture.

Feofan thinks of the figure three-dimensionally, plastically. He clearly imagines how the body is located in space, therefore, despite the conventional background, his figures seem surrounded by space, living in it. Feofan attached great importance to the transfer of volume in painting. His method of modeling is effective, although at first glance it seems sketchy and even careless. Feofan paints the basic tone of the face and clothes with wide, free strokes. On top of the main tone in certain places - above the eyebrows, on the bridge of the nose, under the eyes - he applies light highlights and spaces with sharp, well-aimed strokes of the brush. With the help of highlights, the artist not only accurately conveys the volume, but also achieves the impression of convexity of the form, which was not achieved by the masters of earlier times. Feofan’s figures of saints, illuminated by flashes of light, acquire a special trepidation and mobility.

A miracle is always invisibly present in Theophan’s art. The cloak of Melchizedek covers the figure so quickly, as if it had energy or was electrified.

The icon is exceptionally monumental. The figures stand out in clear silhouette against a shining golden background, laconic, generalized decorative colors sound tense: the snow-white tunic of Christ, the velvety blue maforium of the Mother of God, the green robes of John. And although in the icons Feofana retains the picturesque manner of his paintings, the line becomes clearer, simpler, more restrained.

Feofan’s images contain enormous power of emotional impact; they contain tragic pathos. Acute drama is present in the master’s very picturesque language. Feofan's writing style is sharp, impetuous, and temperamental. He is first and foremost a painter and babbles figures with energetic, bold strokes, applying bright highlights, which gives the faces trepidation and emphasizes the intensity of expression. The color scheme, as a rule, is laconic and restrained, but the color is rich, weighty, and the brittle, sharp lines and complex rhythm of the compositional structure further enhance the overall expressiveness of the images. Theophan the Greek art icon painting

The paintings of Theophanes the Greek were created on the basis of knowledge of life and human psychology. They contain a deep philosophical meaning; the insightful mind and passionate, ebullient temperament of the author are clearly felt.

Almost no icons made by Theophanes have survived to this day. Apart from the icons from the iconostasis of the Annunciation Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin, we do not know reliably any of his easel works. However, with a high degree of probability, the remarkable “Assumption”, written on the reverse side of the “Our Lady of the Don” icon, can be attributed to Theophanes.

The “Assumption” depicts what is usually depicted in icons of this subject. The apostles stand at Mary's funeral bed. The golden figure of Christ with a snow-white baby - the soul of the Mother of God in his hands - goes up. Christ is surrounded by a blue-dark mandola. On either side of it stand two tall buildings, vaguely reminiscent of the two-story towers with the mourners in the Pskov icon of the Dormition.

Theophan's apostles are not like strict Greek men. They huddled around the bed without any order. Not a shared enlightened grief, but each person’s personal feeling - confusion, surprise, despair, sad reflection on death - can be read on their simple faces. Many people would not be able to look at dead Mary. One peeks slightly over his neighbor’s shoulder, ready to lower his head at any moment. The other, huddled in the far corner, watches what is happening with one eye. John the Theologian almost hid behind the high bed, looking out from behind it in despair and horror.

Above Mary’s bed, above the figures of the apostles and saints, rises Christ shining in gold with the soul of the Mother of God in his hands. The apostles do not see Christ; his mandola is already a sphere of the miraculous, inaccessible to human gaze. The apostles see only the dead body of Mary, and this sight fills them with horror of death. They, “earthly people,” are not given the opportunity to know the secret of Mary’s “eternal life.” The only one who knows this secret is Christ, for he belongs to two worlds at once: the divine and the human. Christ is full of determination and strength, the apostles are full of sorrow and inner turmoil. The sharp sound of the colors of the “Assumption” seems to reveal the extreme degree of mental tension in which the apostles find themselves. Not an abstract, dogmatic idea of the bliss beyond the grave and not a pagan fear of earthly, physical destruction, but intense thinking about death, “smart feeling,” as such a state was called in the 18th century - this is the content of the wonderful icon of Theophanes.

In Theophanes’s “Assumption” there is a detail that seems to concentrate the drama of the scene taking place. This candle burning at the bed of the Mother of God. She was not in “The Tithe Dormition” or in “Paromena”. In “The Assumption of the Tithes” Mary’s red shoes are depicted on the stand by the bed, and in Paromensky” a precious vessel is depicted - naive and touching details that connect Mary with the earthly world. Placed in the very center, on the same axis with the figure of Christ and the cherub, the candle in the icon of Theophan seems to be full of special meaning. According to apocryphal legend, Mary lit it before she learned from an angel about her death. A candle is a symbol of the soul of the Mother of God, shining to the world. But for Feofan this is more than an abstract symbol. The flickering flame seems to make it possible to hear the echoing silence of mourning, to feel the coldness and immobility of Mary’s dead body. A dead body is like burnt, cooled wax, from which the fire has disappeared forever - the human soul. The candle burns out, which means that the time of earthly farewell to Mary is ending. In a few moments the shining Christ will disappear, his mandorla held together like a keystone by the fiery cherub. There are many works in world art that would so powerfully make one feel the movement, the transience of time, indifferent to what it is counting down, inexorably leading everything to the end.

The Deesis of the Annunciation Cathedral, regardless of who led its creation, is an important phenomenon in the history of ancient Russian art. This is the first Deesis that has come down to our time, in which the figures of saints are depicted not from the waist up, but at full length. The real history of the so-called Russian high iconostasis begins with it.

The Deesis tier of the iconostasis of the Annunciation Cathedral is a brilliant example of pictorial art. The color range is especially remarkable, which is achieved by combining deep, rich, rich colors. A sophisticated and inexhaustibly inventive colorist, the leading master of Deesis even dares to make tonal comparisons within the same color, painting, for example, the clothes of the Mother of God with dark blue and Her cap with a more open, lightened tone. The artist’s thick, dense colors are exquisitely restrained, slightly dull even in the light part of the spectrum. Then, for example, the unexpectedly bright strokes of red on the image of the book and the boots of the Mother of God are so effective. The manner of writing itself is unusually expressive - broad, free and unmistakably precise.

Conclusion

It is known that in Rus' Theophanes the Greek took part in the painting of dozens of churches. Unfortunately, most of his works have been lost. Unfortunately, it is not known whether a number of first-class works attributed to him belong to him or his students. What is known for certain is that he painted the Church of the Transfiguration in Novgorod.

It is generally accepted to classify the work of Theophanes the Greek as a phenomenon of Russian culture. But in fact, he was a man of exclusively Byzantine culture, both as a thinker and as an artist. He was the last Byzantine missionary in Rus'. His works belonged to the past XIV century, crowning his achievements. They were tragic in nature, as they expressed the worldview of the decline of the Byzantine Empire and were imbued with apocalyptic forebodings of the imminent death of the Holy Orthodox Kingdom. They were full of prophecies of retribution to the Greek world, the pathos of stoicism.

Of course, such painting was in tune with the outgoing Golden Horde Rus'. But it absolutely did not correspond to the new moods, dreams of a bright future, of the emerging power of the Moscow kingdom. In Novgorod, Feofan's work aroused admiration and imitation. Victorious Moscow greeted him favorably, but with the brush of Andrei Rublev, he approved a different style of painting - “lightly joyful,” harmonic, lyrical-ethical.

Theophanes was the last gift of the Byzantine genius to the Russian. The “Russian Byzantine”, the expressively exalted Greek, the gloomy “Michelangelo of Russian painting” was replaced by “Raphael” - Andrei Rublev.

Bibliography

1. Alpatov M. V . Theophanes the Greek. Fine arts [Text] / M.V. Alpatov. M.: 1900. 54 p.

2. Cherny V.D. The art of medieval Rus' [Text] / V.D. Black. M.: “Humanitarian Publishing Center VLADOS”, 1997. 234 p.

3. Letter of Epiphanius the Wise to Kirill of Tverskoy [Text] / Monuments of literature of Ancient Rus' XVI - ser. XV century. M., 1981. 127 p.

4. Lazarev V.N. Feofan the Greek [Text] / V.N. Lazarev. M., 1961. 543 p.

5. Muravyov A.V., Sakharov A.M. Essays on the history of Russian culture IX-XVII centuries. [Text] / A.V. Muravyova, A.M. Sakharov. M., 1984. 478 p.

Posted on Allbest.ru

...Similar documents

The life and work of Theophanes the Greek - the great Russian and Byzantine icon painter, miniaturist and master of monumental fresco paintings. His first work in Novgorod was painting frescoes in the Church of the Transfiguration. Examples of the work of Theophanes the Greek.

course work, added 12/01/2012

Biographies of Andrei Rublev and Theophanes the Greek, compiled on the basis of chronicle evidence. Analysis of the system of value guidelines of great icon painters, differences in worldviews. Features of the painting of the Trinity icon/fresco by both masters.

report, added 01/23/2012

Artistic art of Theophanes the Greek. Analysis, its influence on the history of Russian icon painting. Images, style and content of his works. The work of the painter Andrei Rublev. The philosophical concept of the Trinity icon is the artist’s highest creative achievement.

abstract, added 04/21/2011

Information about Theophanes the Greek in a letter from his contemporary, the ancient Russian writer Epiphanius the Wise, to Abbot Kirill. Frescoes by Theophanes the Greek in the Church of John the Theologian in Feodosia. Painting Moscow churches from 1395 to 1405, fulfilling secular orders.

presentation, added 04/19/2011

Precious decorations of church utensils, attire of princes and boyars in Rus'. The flourishing of Russian icon painting in the age of the greatest Russian saints. The meaning of paint colors in iconography. The work of Theophanes the Greek and Andrei Rublev, ancient principles of composition.

abstract, added 01/28/2012

The causes of iconoclasm in Byzantium and its consequences. Transformation of the Byzantine icon-painting canon towards further subjectivism. The influence of Byzantium on the culture of Ancient Rus'. The work of painters Feofan the Greek and Andrei Rublev.

abstract, added 03/21/2012

The beginning of Russian chronicles is the presentation of historical events in chronological order. Literary works, journalism and printing of Kievan Rus. The works of Theophanes the Greek and Andrei Rublev. Painting and architecture of Ancient Rus'.

presentation, added 05/31/2012

The inadequacy of the early icon to the Christian worldview. Consequences of the iconoclastic movement. Fundamentals of the Byzantine pictorial canon. National style of Russian icon painting of the late XIV - early XV centuries. The works of Theophanes the Greek and Andrei Rublev.

abstract, added 05/10/2012

Cultural and spiritual heritage of the ancient Eastern Slavs. Characteristics of the era: the end of the Tatar-Mongol yoke, the formation of the Moscow state. The work of the great icon painter Theophanes the Greek. Andrey Rublev. Construction of the Moscow Kremlin in the 15th century.

abstract, added 01/10/2008

Art of Novgorod and Pskov of the XIV-XV centuries. Monumental painting by Theophanes the Greek. Novgorod icon painting of the XIV-XV centuries. Features of Tver art. Novgorod and Pskov architecture of the XIV-XV centuries. Meletov frescoes in the Church of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary in Meletov.

There are many cases in the history of Russia when a visiting foreigner increases its glory and becomes national pride. So Theophanes the Greek, a native of Byzantium, a Greek by origin (hence the nickname) became one of the greatest

Choice in favor of Rus'

Most likely, if Theophanes had not decided to radically change his life by coming to Russia instead of Italy in the retinue (as is assumed) of Metropolitan Cyprian, he would have gotten lost among the numerous Byzantine artists. But in Muscovite Rus' he became the first of a brilliant galaxy of icon painters. Despite widespread recognition, the dates of the artist’s birth and death are approximately 1340-1410.

Lack of information

It is known that Theophanes the Greek, whose biography is full of blank spots, was born in Byzantium, worked both in Constantinople itself and in its suburb - Chalcedon. From the frescoes preserved in Feodosia (then Kafa) it is clear that for some time the artist worked in the Genoese colonies - Galata and Kafa. None of his Byzantine works have survived, and world fame came to him thanks to the work done in Russia.

New environment

Here, in his life and work, he had the opportunity to intersect with many great people of that time - Andrei Rublev, Sergius of Radonezh, Dmitry Donskoy, Epiphanius the Wise (whose letter to Archimandrite Kirill is the main source of biographical data of the great icon painter) and Metropolitan Alexei. This community of ascetics and educators did a lot for the glory of Rus'.

The main source of information about Theophanes the Greek

Theophanes the Greek arrived in Novgorod in 1370, that is, a completely mature man and an established artist. He lived here for more than 30 years, until his death. His performance is amazing. According to the testimony of the same Epiphanius the Wise, Theophanes the Greek painted 40 churches in total. The letter to the archimandrite of the Tver Spaso-Afanasyevsky Monastery was written in 1415, after the death of the master, and has survived to this day not in the original, but in a copy of the second half of the 17th century. There are also some chronicle confirmations of facts and additions. One of them reports that in 1378, by order of boyar Vasily Danilovich, the “Greek” Feofan painted the Transfiguration Church, located on the Trade Side of Veliky Novgorod.

Beginning of the Novgorod period

The frescoes of Theophanes the Greek on the walls of this monastery became his first work in Rus' mentioned in documents. They, even preserved in fragments, being in very good condition, have survived to our time, and are among the greatest masterpieces of medieval art. The painting of the dome and walls where the choirs of the Trinity chapel were located is in the best condition. In the depicted figures of the “Trinity” and Macarius of Egypt, the unique style of writing that the brilliant Theophanes the Greek possessed is very clearly visible. The dome preserves a chest-to-chest image, which is the most grandiose. In addition, the figure of the Mother of God has been partially preserved. And in the drum (the part that supports the dome) there are images of John the Baptist. And this is why these frescoes are especially valuable, since, unfortunately, the works created over a number of subsequent years are not documented and are disputed by some researchers. In general, all the monasteries are made in an absolutely new manner - lightly and with wide, free strokes, the color scheme is restrained, even stingy, the main attention is paid to the faces of the saints. In the manner of writing of Theophanes the Greek one can feel his special philosophy.

Rus''s ability to revive

There had not yet been the great victory of Dmitry Donskoy, the raids of the Golden Horde continued, Russian cities were burning, temples were being destroyed. But Russia is so strong because it was revived, rebuilt, and became even more beautiful. Theophan the Greek also took part in the painting of the restored monasteries, who since 1380 worked in Nizhny Novgorod, in the capital of the Suzdol-Nizhegorod principality, which was completely burned in 1378. Presumably, he could take part in the paintings of the Spassky Cathedral and the Annunciation Monastery. And already in 1392, the artist worked at the request of Grand Duchess Evdokia, the wife of Prince Dmitry. Later, the cathedral was rebuilt several times, and the frescoes were not preserved.

Moving to Moscow

Feofan the Greek, whose biography, unfortunately, is very often associated with the word “allegedly,” after Kolomna moves to Moscow. Here, and this is confirmed by the Trinity Chronicle and the well-known letter, he paints the walls and decorates three churches. At this time, he already had his own school, students and followers, with whom, with the active participation of the famous Moscow icon painter Simeon the Black, in 1395, Feofan painted the walls of the Church of the Nativity of Our Lady and the chapel of St. Lazarus in the Kremlin. All work was carried out by order of the same Grand Duchess Evdokia. And again it must be stated that the church has not been preserved; the existing Bolshoi Church stands in its place.

Evil fate haunting the master's work

A recognized genius of the Middle Ages, icon painter Theophanes the Greek, together with his students, began in 1399 to decorate the Archangel Cathedral, which was completely burned by the Khan of the Golden Horde and the Tyumen Principality - Tokhtamysh. From Epiphany’s letter it is known that the master depicted the Moscow Kremlin with all its churches on the walls of the temple. But in the second half of the 16th century, the Italian architect Aleviz the New dismantled the temple and built a new one of the same name, which has survived to this day.

The art of Theophanes the Greek is mostly represented by frescoes, since until the end of his days he painted the walls of churches. In 1405, his creative path intersected with the activities of Andrei Rublev and his teacher - the “elder from Gorodets”, the name given to the Moscow icon painter Prokhor from Gorodets. These three most famous masters of their time together created the cathedral church of Vasily I, in the Annunciation Cathedral.

The frescoes have not survived - the court church was, naturally, rebuilt.

Unconditional evidence

What has been preserved? What memory of himself did the great Theophanes the Greek leave for his descendants? Icons. According to one of the existing versions, the iconostasis that has survived to this day was originally painted for the Assumption Cathedral in Kolomna. And after the fire of 1547 it was moved to the Kremlin. In the same cathedral there was “Our Lady of the Don,” an icon with her biography. Being one of the many modifications of “Tenderness” (another name is “The Joy of All Joys”), the image is covered in the legend of its amazing help in the victory won by the army of Grand Duke Dmitry over the hordes of the Golden Horde in 1380. After the Battle of Kulikovo, both the prince and the patron icon received the prefix “Donskoy” and “Donskaya”. The image itself is two-sided - on the reverse side there is the “Assumption of the Mother of God”. The priceless masterpiece is kept in the Tretyakov Gallery. Many analyzes have been carried out, and it can be argued that its author is certainly Theophanes the Greek. The icons “Four-digit” and “John the Baptist - Angel of the Desert with Life” belong to the icon painter’s workshop, but his personal authorship is disputed. The works of masters of his school include a fairly large icon, painted in 1403 - “The Transfiguration”.

Lack of biographical information

Indeed, very few documented works of the great master exist. But Epiphanius the Wise, who knew him personally and was friends with him, so sincerely admires his talent, diversity of talent, breadth of knowledge that it is impossible not to believe his testimony. The Savior of Theophanes the Greek is often cited as an example of the work of the Greek school with a distinctly Byzantine style of writing. This fresco, as noted above, is the most grandiose of all the surviving fragments of wall paintings of the Novgorod Cathedral discovered in 1910. It is one of the world-famous great architectural monuments of medieval Rus'. Another image of the Savior, which belongs to the work of the master, is located in the Kremlin on the Annunciation iconostasis.

One of the great "Trinities"

Among the frescoes of this cathedral there is another masterpiece of world significance, the author of which is Theophanes the Greek. “Trinity” is perfectly preserved and is located in the choir. The canonical plot of “The Hospitality of Abraham” lies at the heart of this work, although his figure on the fresco has not been preserved, the “Trinity” deserves a hitherto unrealized detailed study. In his letter, Epiphanius admires the many talents of Theophanes the Greek - the gift of a storyteller, the talent of an intelligent interlocutor, and the extraordinary manner of writing. According to the testimony of this man, the Greek, among other things, had the talent of a miniaturist. He is characterized as an icon painter, a master of monumental fresco painting and a miniaturist. “He was a deliberate book painter” - this is how this praise sounds in the original. The authorship of miniatures from the Psalter, owned by Ivan the Terrible and kept in the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, is attributed to Theophanes the Greek. He is also supposed to be the miniaturist of The Gospel of Fyodor the Cat. The fifth son, the direct ancestor of the Romanovs, was the patron of Theophanes the Greek. The book is superbly designed. Its skillful headbands and initials made in gold are striking.

The identity of Theophanes the Greek

Before Theophanes, many icon painters, and even his contemporaries, relied primarily on tracing (a thin outline previously made from the original) in the production of their works. And the Greek’s free style of writing surprised and captivated many - “he seemed to paint the painting with his hands,” Epiphanius admires, calling him a “wonderful husband.” He certainly had a pronounced creative individuality. The exact date of death of the genius is not known; in some places it is even said that he died after 1405. In 1415, the author of the famous letter mentions the Greek in the past tense. Therefore, he was no longer alive. And Feofan was buried, again presumably, somewhere in Moscow. All this is very sad and only says that Russia has always experienced many troubled times, during which the enemies destroyed the very memory of the people who made up its glory.

Opinion of V. Lazarev

In order to trace the main stages of the work of Theophanes the Greek, it is necessary to study the cultural and historical situation that influenced the formation of him as a person and artist, to find out his significance in the Byzantine culture of the 14th century, the reasons that prompted him to emigrate, and also to understand what influence he had on Byzantine master Russian environment.

Theophanes the Greek, born in the 30s of the 14th century, entered a period of conscious life in the midst of “hesychast disputes.” He undoubtedly heard conversations about the nature of the Tabor light, about divine energies, about the communication of the deity to man, about “smart” prayer. It is possible that he even took part in these discussions that worried the minds of Byzantine society. Epiphanius' testimony that Theophanes was “a glorious sage, a very cunning philosopher” speaks of the artist’s erudition and the breadth of his spiritual needs. But what was Feofan’s direct attitude towards hesychasm remains unknown to us. One thing is certain - he could not remain unaffected by the largest ideological movement of his time. The severity of Theophan's images, their special spirituality, their sometimes exaggerated ecstasy - all this is connected with hesychasm, all this follows from the essence of hesychast teaching. However, Feofan’s works also testify to something else: they indisputably speak of the master’s deep dissatisfaction with this teaching. Theophan did not isolate himself in church dogma, but, on the contrary, largely overcame it. He thought much more freely than the hesychasts. And as he moved further away from Constantinople in his wanderings, his horizons became wider and wider and his beliefs became more and more independent.

Feofan’s creative growth should have been greatly facilitated by his work in Galata, where he came into close contact with Western culture. He wandered through the narrow streets of Galata, admired the beauty of its palazzos and temples, became acquainted with works of Italian craftsmanship, saw luxuriously dressed Genoese merchants, observed free Western morals, unusual for a Byzantine, and watched the galleys arriving at the port, bringing goods from Italy. The life of this Genoese colony, which was a powerful outpost of early Italian capitalism, was full of business. And this is precisely why it differed sharply from the economic structure of Byzantine society, which was in no hurry and continued to live in the old fashioned way. Probably, Theophanes, as a man of outstanding intelligence, should have understood that the center of world politics was steadily moving from Byzantium to the Italian trading republics and that the Roman power was heading towards rapid decline. Contemplating the Golden Horn from the fortress towers of Galata and Constantinople spread out on its shore, the best buildings of which, after the pogrom perpetrated by the crusaders, lay in ruins or were neglected and abandoned, Theophanes had every opportunity to compare the impoverished capital of his once great homeland with the rapidly growing and richest Genoese colony , which, like an octopus, extended its tentacles in all directions, establishing one after another powerful trading posts in the countries of the East and on the Black Sea coast. And this comparison was supposed to give rise to deep bitterness in Feofan’s soul. In Galata, he drank from that new life, which carried with it the fresh trends of early humanism.

Having come into contact with Western culture, Theophanes could choose two paths for himself: either to remain in Byzantium and plunge headlong into endless theological debates about the nature of the Tabor light, or to emigrate to Italy, as many of his brethren did and as those who later joined the Italian humanists Manuel Chrysolor and Vissarion of Nicaea. Feofan did not follow any of these paths. Dissatisfied with the current situation in Byzantium, he decided to leave his homeland. But he directed his steps not to the west, but to the east - first to Caffa, and then to Rus'. And here his work entered a new phase of development, which would have been impossible in the fanatical and intolerant Byzantium, where his art, which had outgrown its narrow confessional framework, would undoubtedly sooner or later be ostracized.

There was another reason that pushed Feofan to emigrate. Although his activity unfolded in the second half of the 14th century, when a new style, hostile to early Palaeologian neo-Hellenism, had already won in Byzantium, Theophanes continued to remain entirely associated with the free pictorial traditions of the first half of the century. To some extent, he was the last representative of the great traditions of early Palaiologan art.

And therefore he had to feel the crisis of the latter especially acutely. The approaching academic reaction with its narrow monastic spirit could not help but frighten Theophan, since it ran counter to his artistic views. Anyone who has at least once seen the Theophanian paintings in the Church of the Transfiguration of the Savior, with their so clearly expressed picturesqueness, and mentally compared them with the dry, tortured works of the Constantinople school of the second half of the 14th century, will immediately become obvious to the deep abyss that lies between these monuments. To the great happiness of Theophanes, his art was a belated flower in the withered field of Byzantine artistic culture, as belated as the philosophy of Giordano Bruno or the humanism of Shakespeare appeared in relation to the Renaissance. We constantly encounter similar processes of uneven development in history. And only taking into account the uniqueness of this kind of phenomena can we assign the correct historical place to the art of Theophanes the Greek.

The historical situation we have outlined, which developed in Byzantium in the 40-60s of the 14th century, largely explains the reasons for Theophanes’ emigration from Byzantium. He fled from the impending ecclesiastical and artistic reaction, he fled from what was deeply hostile to his views and beliefs. If Theophanes had not left Byzantium, he would probably have turned into one of those faceless epigones of Byzantine painting, whose work emanates coldness and boredom. Having left for Rus', Theophanes found here such a wide field of activity and such a tolerant attitude towards his bold innovations, which he could never have found in the materially and spiritually impoverished Byzantium.

Epiphanius reports that Theophanes worked in Constantinople, Chalcedon, Galata and Caffa before arriving in Novgorod. Chalcedon and Galata are located near the capital of the Byzantine Empire (Galata, strictly speaking, is even one of its quarters), while Kaffa lies on the way from Constantinople to Russia. It would seem that this testimony of a writer well informed about the artist’s life leaves no doubt as to Feofan’s belonging to the Constantinople school. Nevertheless, a very artificial and completely unconvincing theory was developed, according to which Theophanes came not from the Constantinople, but from the Cretan school. This theory, first developed by Millet, found recognition in Diehl and Breye. Later, the “Cretan” theory was replaced by the even less substantiated “Macedonian” theory. The latter was put forward by B.I. Purishev and B.V. Mikhailovsky, who arbitrarily made Feofan a Macedonian master. Only M.V. Alpatov, D.V. Ainalov and Talbot Raie firmly considered Feofan as a Constantinople artist. Since the question of which school Theophanes came from is by no means idle, since our understanding of the general process of development of Byzantine painting depends on one or another of its solutions, this question should be discussed in detail, otherwise we will face a very real danger of incorrectly illuminating the problem of schools and artistic traditions in Byzantine art of the 14th century.

Millet was the first to connect Theophanes with the Cretan school, which acquired in his major work on the iconography of the Gospel a meaning completely inappropriate for its real specific gravity. Apparently, Millet followed in the footsteps of N.P. during the reconstruction of the Cretan school. Kondakova and N.P. Likhacheva. It is even possible that the idea that Theophanes belonged to the Cretan school was suggested to him by the following cursory remark by N.P. Likhacheva: “Theophanes, Rublev’s collaborator and almost teacher, was an innovator and representative of that neo-Byzantine, later Italo-Greek-Cretan school, with which the “Tenderness” type is associated. Be that as it may, but by attributing Theophanes to the Cretan school and at the same time attributing three fresco cycles of Novgorod (the Church of the Assumption on Volotovo Field, the Church of Theodore Stratilates, the church in Kovalevo) to the Macedonian school, Millet and Dil, who followed in his footsteps, thereby fell into the greatest a contradiction, which P.P. drew attention to at one time. Muratov: three monuments of the same direction and one pictorial style (paintings of the Transfiguration of the Savior, the Church of the Assumption on Volotovo Field and Theodore Stratilates) turned out to be completely arbitrarily distributed between two schools, fundamentally different from each other - Cretan and Macedonian. This state of affairs could only arise because Millet based his division of monuments into schools not on a stylistic, but on an iconographic principle. If the venerable French scientist had based his judgment on direct knowledge of Novgorod paintings, he would have been convinced that all these three fresco cycles came from one school - from the school of Theophanes the Greek, who had nothing to do with either Crete or Macedonia, but was a typical representative of the metropolitan Constantinople manner...

Epiphanius's letter alone leaves no doubt as to Theophanes's belonging to the Constantinople school. The master who painted many temples in Constantinople itself, in Chalcedon and Kaffa, is unlikely to have come here from Crete or Macedonia, especially since both of these places were provinces compared to the capital. The wonderful art of Feofan is marked with a purely metropolitan stamp; it breathes the metropolitan spirit. And this art finds its closest stylistic analogies in the monuments of Constantinople, and not at all in the works of Cretan and Macedonian masters.

If we take the images of the forefathers most characteristic of Theophanes the Greek from the Church of the Transfiguration in Novgorod and try to find the closest analogy for them among the monuments of Byzantine craftsmanship, then such, undoubtedly, will be the patriarchs from the southern dome of the internal narfik of Kakhrie Jami. Although the figures of the patriarchs are made here using the mosaic technique, nevertheless they are so close, both in their general spirit and in detail, to the Theophanian saints that any doubts about the metropolitan origin of our master immediately disappear. In Kahrie's mosaics we encounter the same majestic severity of images, the same freedom of compositional solutions, and the same bold asymmetrical shifts. The figures of Adam, Seth, Noah, Eber, Levi, Issachar, Dan, and Joseph show particular typological closeness to the Theophanes forefathers. Some of the figures of the prophets and kings of Israel in the northern dome of the same internal narfik also have many points of contact with Theophanian images (cf., for example, the figures of Aaron, Hor and Samuel).

Although Theophanes’s style of writing is extremely individual, it is still possible to find direct sources for it in the monuments of the Constantinople school. These are, first of all, the frescoes of the Kakhrie Jami refectory, which appeared at the same time as the mosaics, i.e. in the second decade of the 14th century. Here the heads of individual saints (especially David of Thessalonica) seem to have come out from under Theophan’s brush. They are written in an energetic, free style of painting, based on the extensive use of bold strokes and so-called marks with which to model faces. These highlights and marks are especially actively used in finishing the forehead, cheekbones, and ridge of the nose. This technique in itself is not new; it is very common in the painting of the 14th century, mainly in its first half. What brings Kakhrie Jami’s paintings and Feofan’s frescoes together is the remarkable accuracy in the distribution of highlights, which always fall into the right place, thanks to which the form acquires strength and constructiveness. In the monuments of the provincial circle (as, for example, in the paintings of the cave temple of Theoskepastos in Trebizond) we will never find such precision in modeling. Only after becoming acquainted with such provincial works do you finally become convinced of the metropolitan training of Theophanes, who perfectly mastered all the subtleties of Constantinople craftsmanship.

The basic principles of Feofanov’s art also point to the Constantinople school - intense psychologism of images, extraordinary sharpness of individual characteristics, dynamic freedom and picturesqueness of compositional structures, exquisite “tonal coloring”, overcoming the motley multicolor of the eastern palette, and finally, an extraordinary decorative flair, going back to the best traditions of Tsaregrad painting . With all these facets of his art, Feofan appears to us as a metropolitan artist living by the aesthetic ideals of Constantinople society. And its strength lies in the fact that it starts not from the second, but from the first stage in the development of Paleologian painting, when the latter was still imbued with a living creative spirit. Therefore, a great gain for Russian artistic culture was the arrival to us of such a master, who was the bearer of the best that gave birth to Tsaregrad neo-Hellenism of the 14th century.

Literature: Alpatov L.V. and others. Art. Painting, sculpture, graphics, architecture. Ed. 3rd, rev. and additional Moscow, "Enlightenment", 1969.

Works by Theophanes the Greek. And horses, frescoes, paintings

|

Apostle Peter. 1405. |

|

Apostle Peter. 1405. Fragment Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

John the Baptist. 1405 Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

John the Baptist. 1405. Fragment Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

Our Lady. 1405 Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

Our Lady. 1405. Fragment Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

Transfiguration of the Lord, 1403 To view a larger image |

|

Apostle Paul. 1405 Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

Apostle Paul. 1405. Fragment Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

Dormition of the Mother of God, XIV century State Tretyakov Gallery To view a larger image |

|

Archangel Gabriel. 1405 Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

Archangel Gabriel. 1405. Fragment Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

Jesus Pantocrator Painting in the dome of the Church of the Transfiguration, Ilyina street, Novgorod, 1378 To view a larger image |

|

Our Lady of the Don. Around 1392 State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow To view a larger image |

|

Basil the Great. 1405. Fragment Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

John Chrysostom. 1405. Fragment Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

Prophet Gideon. 1405 Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

Fresco Forefather Isaac Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

Savior is in power. 1405 Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

Fresco Archangel, 1378 Ilyina street, Novgorod To view a larger image |

|

Fresco Abel, 1378 Fragment of a fresco in the Church of the Transfiguration, Ilyina street, Novgorod To view a larger image |

|

Daniel Stylite, 1378 Fragment of a fresco in the Church of the Transfiguration, Ilyina street, Novgorod To view a larger image |

|

Archangel Michael. 1405 Cycle of details of icons of the Deesis tier of the iconostasis Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin To view a larger image |

|

Fresco fragment, 1378 Fragment of a fresco in the Church of the Transfiguration, Ilyina street, Novgorod To view a larger image |

|

Fresco fragment, 1378 Fragment of a fresco in the Church of the Transfiguration, Ilyina street, Novgorod To view a larger image |

|

Old Testament Trinity, 1378 Fragment of a fresco in the Church of the Transfiguration, Ilyina street, Novgorod To view a larger image |

Theophanes the Greek. appeared in Novgorod in the 70s of the 14th century. He was one of those great Byzantine emigrants, among whom was the Cretan Domenico Theotokopouli, famous by El Greco. Impoverished Byzantium was no longer able to provide work for its many artists. In addition, the political and ideological situation was less and less favorable for the rise of Byzantine art, which entered a period of crisis in the second half of the 14th century. The victory of the hesychasts led to increased intolerance and to the strengthening of a dogmatic way of thinking, which gradually suppressed the weak shoots of humanism of the early Palaeologian culture. Under these conditions, the best people of Byzantium left their homeland in search of shelter in a foreign land. This is exactly what Theophanes the Greek did. In free Novgorod, among the distant Russian expanses, he found the creative freedom that he so lacked in Byzantium. Only here did he emerge from under the jealous tutelage of the Greek clergy, only here did his remarkable talent unfold to its full extent.

A most interesting letter from the famous ancient Russian writer Epiphanius to his friend Kirill Tverskoy 35 has been preserved. This message, written around 1415, contains very valuable information regarding the life and work of Theophanes the Greek, whom Epiphanius knew well personally. From a comparison of the chronicle news with the facts reported by Epiphanius, it is clear that Theophanes was both a painter and a miniaturist, that he came to Russia as a mature master (otherwise he would not have been allowed to paint churches in Constantinople and a number of other Byzantine cities), that he worked not only in Novgorod and Nizhny, but also in grand-ducal Moscow, where he arrived no later than the mid-90s and where he collaborated with Andrei Rublev, that everywhere he aroused surprise with the liveliness and sharpness of his mind and the boldness of his pictorial daring. Epiphanius's message allows us to draw another important conclusion. It leaves no doubt about the Constantinople origin of Theophanes, since all the cities mentioned by Epiphanius, in which the artist worked before arriving in Rus', directly point to Constantinople as his homeland. In addition to Constantinople itself, this is Galata - the Genoese quarter of the Byzantine capital; this is Chalcedon, located on the opposite side of the mouth of the Bosphorus; this is, finally, the Genoese colony of Caffa (present-day Feodosia), lying on the way from Constantinople to Russia. The close stylistic similarity of the painting of the Savior on Ilyin, executed by Theophanes, with the frescoes of the pareklesium and the mosaics of the internal narfik of Kakhriye Jami (southern and northern domes) only confirms Epiphanius’s testimony about the artist’s Constantinople origin. Arriving in Rus', Feofan acted here as a successor of the late Palaeologian With. 178

With. 179¦ traditions, marked by the stamp of dry, soulless eclecticism, and advanced early Palaeologian ones, still quite vividly connected with the “Palaeologian Renaissance,” which reached its peak during the first half of the 14th century. And it so happened that Theophanes sowed first in Novgorod, and then in Moscow, those seeds that could no longer produce rich shoots on the parched soil of Byzantium.

35 See: Lazarev V.N. Theophanes the Greek and his school. M., 1961, p. 111–112.

Arriving in Novgorod, Feofan, naturally, began to take a close look at local life. He could not indifferently pass by those broad heretical movements that unfolded with such force in this large craft center. Just during the years of the appearance of Theophan the Greek in Novgorod, the heresy of the Strigolniks spread here, directed with its edge against the church hierarchy. Contact with the sober Novgorod environment and such ideological movements as strigolism was supposed to introduce a fresh stream into Feofan’s work. It helped him move away from Byzantine dogmatism, expanded his horizons and taught him to think not only more freely, but also more realistically. Novgorod art taught him this. Probably, first of all, his attention was attracted by the remarkable Novgorod paintings of the 12th century, which could not help but amaze him with the power and strength of their images, as well as the boldness of the pictorial solutions. Perhaps Feofan also visited Pskov, otherwise it would be difficult to explain such a striking similarity between the Snetogorsk frescoes and his own works. Acquaintance with this kind of works contributed to Feofan’s familiarization with that laconic, strong and figurative artistic language that the people of Novgorod and Pskov liked so much.

[Color ill.] 80. Seraphim. Fresco in the dome |

[Color ill.] 81. Trinity. Fresco in the choir chamber. Detail |

[Color ill.] 82. Angel from Trinity. Fresco in the choir chamber Detail |

[Color ill.] 86. Nativity. Fresco on the south wall. Detail |

| Theophanes the Greek. Frescoes of the Church of the Transfiguration, Novgorod. 1378 | |||

The only monumental work of Feofan that has survived on Russian soil is the frescoes of the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyin Street in Novgorod. This church was built With. 179

With. 180¦ in 1374 36 and painted four years later “at the behest” of boyar Vasily Danilovich and residents of Ilinaya Street 37. The painting of the Church of the Savior has reached us in a relatively good, but, unfortunately, fragmentary form. In the apse, fragments of the holy order and the Eucharist have survived, on the southern altar column - part of the figure of the Mother of God from the Annunciation scene, on the vaults and adjacent walls - fragments of Gospel scenes (Baptism, Nativity, Presentation, Christ's Preaching to the Apostles), on the eastern wall - the Descent of St. Spirit, on the walls and arches - the half-erased remains of figures and half-figures of saints, in the dome - Pantocrator, four archangels and four seraphim, in the piers of the drum - the forefathers Adam, Abel, Noah, Seth, Melchizedek, Enoch, the prophet Elijah and John the Baptist. The most significant and best-preserved frescoes decorate the north-western corner chamber in the choir (in one 14th-century manuscript it is called the Trinity Chapel). Along the bottom of the chamber there was an ornamental frieze made of boards; above there were frontally placed figures of saints, a half-figure of the Sign with the image of the Archangel Gabriel (on the southern wall, above the entrance) and a throne with four saints approaching it on the eastern and adjacent walls; Apparently, the composition Adoration of the Sacrifice, popular in the 13th–14th centuries, was presented here: on the throne stood a paten with the naked infant Christ lying on it. Above the second register stretched a narrow decorative frieze, consisting of diagonally lying bricks, painted in compliance with all the rules of perspective. At the top was the main and best-preserved belt with five pillars, the Old Testament Trinity, medallions with John Climacus, Arsenius and Akaki and the figure of Macarius of Egypt.

36 I Novgorod Chronicle under 1374 [Novgorod first chronicle of the older and younger editions, p. 372].

37 III Novgorod Chronicle under 1378 [Novgorod Chronicles. (So called Novgorod second and Novgorod third chronicles), p. 243]. M. K. Karger (On the question of the sources of chronicle records about the activities of the architect Peter and Theophan the Greek. - Proceedings of the Department of Old Russian Literature of the Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House) of the USSR Academy of Sciences, XIV. M.–L., pp. 567–568) believes that the evidence from the late III Novgorod Chronicle is based on a lost old inscription located in the Church of the Transfiguration.

We are deprived of the opportunity to restore in detail the decorative decoration of the church, since only minor fragments of it have survived. Undoubtedly, the frescoes below the base of the drum With. 180