Biography of Niccolo. Biography of Machiavelli Niccolo. Worldview and ideas

Niccolo Machiavelli is an outstanding Italian politician, thinker, historian, Renaissance writer, poet, military theorist. He was born on May 3, 1469 in an impoverished noble family. His small home was the village of San Casciano, located near Florence. Machiavelli received a good education, thanks to his excellent knowledge of Latin he could read the original of ancient authors, had an excellent idea of the Italian classics, but did not share the admiration of humanists for the era of antiquity.

The political biography of Niccolo Machiavelli dates back to 1498, he acts as secretary of the Second Chancellery, in the same year he was elected secretary of the Council of Ten, which was to be responsible for the military sphere and diplomacy. Over the course of 14 years, Machiavelli carried out a large number of government orders, as part of embassies he traveled to various Italian states, as well as to Germany and France, compiled certificates and reports on current political issues, and conducted extensive correspondence. Acquaintance with the heritage of the ancients, the experience of the state, diplomatic service became an invaluable tool in the subsequent creation of social and political concepts.

In 1512, Machiavelli had to resign because of the Medici who came to power, he was expelled from the city as a republican for a year, and the next year he was arrested as an alleged participant in the conspiracy and tortured. Machiavelli firmly defended his innocence, in the end he was pardoned and sent to the small estate of Sant'Andrea.

The most intense period of his creative biography is connected with his stay in the estate. Here he writes a number of works devoted to political history, the theory of military affairs, and philosophy. So, at the end of 1513, the treatise "The Sovereign" was written (published in 1532), thanks to which the name of its author entered the world history forever. In this essay, Machiavelli argued that the end justifies the means, but at the same time, the “new sovereign” should pursue goals related not to personal interests, but to the common good - in this case, it was about uniting politically fragmented Italy into a single strong state. It was the unlimited power of the ruler, according to the convinced patriot Machiavelli, that could be the only way to put an end to the troubles of his native country. For the sake of this good goal, justice and morality, the interests of citizens and the church can be neglected.

The works of Machiavelli were received with enthusiasm by his contemporaries and enjoyed great success. By his last name, a system of politics was called Machiavellianism, which does not neglect any of the ways to achieve the goal, regardless of their compliance with moral standards. In addition to the “Sovereign”, famous throughout the world, the most significant works of Machiavelli are considered to be “Treatise on the Art of War” (1521), “Discourse on the First Decade of Titus Livius” (1531), and also “History of Florence” (1532). He began writing this work in 1520, when he was summoned to Florence and appointed historiographer. The customer of the "History" was Pope Clement VII. In addition, being a multi-talented person, Niccolo Machiavelli wrote works of art - short stories, songs, sonnets, poems, etc. In 1559, his writings were included by the Catholic Church in the "Index of Forbidden Books".

In the last years of his life, Machiavelli made many unsuccessful attempts to return to stormy political activity. In the spring of 1527, his candidacy for the post of Chancellor of the Florentine Republic was rejected. And in the summer, on June 21 of the same year, while in his native village, the outstanding thinker died. The place of his burial has not been established; in the Florentine church of Santa Croce there is a cenotaph in his honor.

(Italian) Russian and contained a request to recognize the right of his family to the disputed lands of the Pazzi family.Carier start

In the life of Niccolo Machiavelli, two stages can be distinguished: during the first, he was mainly involved in public affairs. In 1512, the second stage began, marked by the forced removal of Machiavelli from active politics and the writing of works that later made his name famous.

| External images | |

|---|---|

| Signoria Square | |

| florence cathedral | |

Machiavelli's life passed into an interesting but dangerous era, when the Pope could have an entire army, and the rich city-states of Italy fell under the rule of foreign states - France, Spain or the Holy Roman Empire. It was a time of unreliable alliances, corrupt mercenaries who abandoned their rulers without warning, when power collapsed in a few days and was replaced by a new one. Perhaps the most significant event in the series of these erratic upheavals was the fall of Rome in 1527. Wealthy cities like Genoa suffered much the same as Rome did five centuries ago when it was burned down by the barbarian Germanic army.

In 1494, the army of the French King Charles VIII entered Italy and reached Florence in November. The young Piero di Lorenzo Medici, whose family ruled the city for almost 60 years, hurriedly set off for the royal camp, but only achieved the signing of a humiliating peace treaty, the surrender of several key fortresses and the payment of a huge indemnity. Piero had no legal authority to make such an agreement, still less without the sanction of the Signoria. As a result, he was expelled from Florence by the indignant people, and his house was plundered.

The monk Savonarola was placed at the head of the new embassy to the French king. During this troubled time, Savonarola became the true master of Florence. Under his influence, the Florentine Republic was restored in 1494 and the republican institutions returned. At the suggestion of Savonarola, the "Great Council" and the "Council of Eighty" were established.

After the execution of Savonarola, Machiavelli was again [ ] was elected to the Council of Eighty, responsible for diplomatic negotiations and military affairs, already thanks to the authoritative recommendation of the Prime Secretary of the Republic, Marcello Adriani (Italian) Russian, a well-known humanist who was his teacher.

Formally, the First Chancellery of the Florentine Republic was in charge of foreign affairs, and the Second Chancellery was in charge of internal affairs and the city militia. But often such a distinction turned out to be very arbitrary, and current affairs were decided by the one who was more likely to succeed through connections, influence or abilities.

It was in this position that from 1499 to 1512, on behalf of the government, Niccolò carried out diplomatic missions on numerous occasions at the courts of Louis XII of France, Ferdinand II, and at the Papal Court in Rome.

At that time, Italy was fragmented into a dozen states, in addition, the wars of France and the Holy Roman Empire for the Kingdom of Naples began. Wars then were waged by mercenary armies and Florence had to maneuver between strong rivals, and Machiavelli carried out diplomatic relations with them. In addition, the siege of the insurgent Pisa took a lot of time and effort from the government of Florence and its plenipotentiary representative to the army, Niccolo Machiavelli.

On January 14, 1501, Machiavelli was able to return to Florence again. He reached the venerable, by Florentine standards, the age of thirty-two years, held a position that provided him with a high position in society and a decent salary. In August of the same year, Niccolo married a lady from an old and illustrious family - Marietta Corsini.

The Corsini family occupied a higher rung in the social hierarchy than the Machiavelli branch to which Niccolò belonged. However, this marriage was mutually beneficial: on the one hand, kinship with Corsini represented Niccolò's ascent up the social ladder, and on the other hand, Marietta's family got the opportunity to take advantage of Machiavelli's political connections.

Niccolo felt deep sympathy for his wife, they had five children. Over the years, thanks to daily efforts and cohabitation, both in sorrow and in joy, their marriage, concluded for the sake of social convention, turned into love and trust. Remarkably, both in the first will of 1512 and in the last will of 1523, Niccolo chose his wife as the guardian of his children, although male relatives were often appointed.

Being on diplomatic business abroad for a long period, Machiavelli usually started relationships with other women.

Influence of Cesare Borgia

From 1502 to 1503, Niccolo was ambassador at the court of Duke Cesare Borgia, son of Pope Alexander VI, a very smart and successful military leader and ruler who expanded his possessions in central Italy with a sword and intrigues. Cesare was always bold, prudent, self-confident, firm, and sometimes cruel.

In June 1502, the victorious army of Borgia, clanging their weapons, approached the borders of Florence. The frightened republic immediately sent ambassadors to him for negotiations - Francesco Soderini, Bishop of Volterra, and Secretary of the Ten Niccolò Machiavelli. On June 24 they appeared before the Borgia. In a report to the government, Niccolò noted:

“This sovereign is beautiful, majestic and so militant that any great undertaking is a trifle for him. He does not let up if he longs for glory or new conquests, just as he knows neither weariness nor fear. ..and also won the unfailing favor of Fortune" .

In one of his early works [ ] Machiavelli noted:

Borgia has one of the most important attributes of a great man: he is a skilled adventurer and knows how to use the chance that has fallen to him to the greatest advantage for himself.

The months spent in the company of Cesare Borgia served as an impetus for Machiavelli's understanding of the ideas of "mastery of government, independent of moral principles", which were later reflected in the treatise "The Emperor". Apparently, due to a very close relationship with "Lady Luck", Cesare was very intriguing to Niccolò.

| External images | |

|---|---|

| Page of the manuscript "Sovereign" | |

| Letter from Paolo Vettori October 10, 1513 | |

Machiavelli constantly in his speeches and reports criticized the "soldiers of fortune", calling them treacherous, cowardly and greedy. Niccolò wanted to play down the role of the mercenaries in order to defend his proposal for a regular army that the Republic could easily control. Having its own army would allow Florence not to depend on mercenaries and French help. From Machiavelli's letter:

“The only way to gain power and strength is to pass a law that would govern the army being created and keep it in proper order. ».

In December 1505, the Ten finally commissioned Machiavelli to start creating a militia. And on February 15, a select detachment of militia pikemen paraded through the streets of Florence to the enthusiastic exclamations of the crowd; all the soldiers were in well-fitting red and white (the colors of the city's flag) uniform, "in cuirasses, armed with pikes and arquebuses." Florence has its own army.

Machiavelli became an "armed prophet".

"That is why all the armed prophets won, and all the unarmed perished, for, in addition to what has been said, it should be borne in mind that the temper of people is fickle, and if it is easy to convert them to your faith, then it is difficult to keep them in it. Therefore, you need to be prepared by force make believe those who have lost faith". Niccolo Machiavelli. Sovereign

In the future, Machiavelli was an envoy to Louis XII, Maximilian I of Habsburg, inspected fortresses, and even managed to create cavalry in the Florentine militia. He accepted the surrender of Pisa and put his signature under the surrender agreement.

When the Florentine people, having learned about the fall of Pisa, indulged in jubilation, Niccolò received a letter from his friend Agostino Vespucci: “You have done an impeccable job with your army and helped to bring closer the time when Florence regained its rightful possession.”

Filippo Casavecchia, who never doubted Niccolo's abilities, wrote: “I do not believe that idiots will comprehend the course of your thoughts, while there are few wise ones, and they are not often found. Every day I come to the conclusion that you surpass even those prophets that were born among the Jews and other nations.

Return of the Medici to Florence

Machiavelli was not dismissed by the new rulers of the city. But he made several mistakes, continuing to constantly express his thoughts on topical issues. Although no one asked him and his opinion was very different from the domestic policy pursued by the new authorities. He opposed the return of property to the returning Medici, offering to pay them simply compensation, and the next time in the appeal "To Palleschi" (II Ricordo ag Palleschi), he urged the Medici not to trust those who defected to their side after the fall of the republic.

Opala, return to service and resignation again

Machiavelli found himself in disgrace and deprived of a livelihood, and in 1513 he was also accused of conspiring against the Medici and arrested. But even under torture on the rack, he denied his involvement and was eventually released, but only thanks to an amnesty being freed from death row, Niccolo retired to his estate in Sant'Andrea in Percussina near Florence and began writing books that secured its place in the history of political philosophy.

From a letter to Niccolo Machiavelli:

I get up at sunrise and go to the grove to look at the work of woodcutters cutting down my forest, from there I follow the stream, and then to the bird current. I go with a book in my pocket, either with Dante and Petrarch, or with Tibull and Ovid. Then I go to an inn on the high road. There it is interesting to talk with people passing by, to learn about the news in foreign lands and at home, to observe how different the tastes and fantasies of people are. When the dinner hour comes, I sit with my family at a modest meal.

When evening comes, I return home and go to my workroom. At the door, I throw off my peasant dress, all covered in mud and slush, put on royal court clothes and, dressed in a worthy manner, I go to the ancient courts of the people of antiquity. There, graciously received by them, I satiate myself with the only food suitable for me, and for which I was born. There I do not hesitate to talk to them and ask about the meaning of their deeds, and they, in their inherent humanity, answer me. And for four hours I do not feel any anguish, I forget all worries, I am not afraid of poverty, I am not afraid of death, and I am all transferred to them.

Cover of the book "Mandrake" In November 1520 he was called to Florence and received the post of historiographer. Wrote "History of Florence" in the years 1520-1525. Initially, it was only a year's work, but Niccolo was able to convince the customers of the need to continue the work. His salary was increased and the work lasted almost 5 years. The Pope, having read the book, also gave Machiavelli a prize of 100 gold florins. He wrote several plays - "Klitsia", "Belfagor", "Mandragora" - which were staged with great success.

Machiavelli was not trusted as an official of the former regime. He filed all kinds of petitions, asked friends to put in a word about him. He was entrusted with one-time diplomatic missions of the pontiff, and, finally, he received a new position when the Habsburgs began to threaten the republic. The pontiff instructed Machiavelli to go along with the military architect Pedro Navarro - a former pirate, but already a specialist in conducting a siege - to inspect the walls of Florence and strengthen them in connection with a possible siege of the city. Niccolo was chosen because he was considered an expert in military affairs: after all, he wrote an entire book “On the Art of War”, besides, an entire chapter in it was devoted to the sieges of cities - and, by common opinion, was the best in the whole book. Some of Niccolò's book advice was far from reality, but the mere fact of the authorship of such a book made him an expert in fortification in the eyes of the Pope. The support of Guicciardini and Strozzi's friends also played a role - they successfully discussed this with the pontiff.

- On May 9, 1526, the Council of the Hundred, at the request of Clement VII, established a new body in the government of Florence - the College of Five to strengthen the walls, Niccolo Machiavelli was appointed its secretary.

But Machiavelli's expectations for a return to work and well-deserved honors failed. In 1527, after Rome was sacked and the pope lost all influence over Florence, republican rule was restored in it. Machiavelli put forward his candidacy for the post of secretary of the College of Ten. But he was not elected, the new government no longer needed him.

External images of the cenotaph in his honor is in the Church of Santa Croce in Florence. The inscription is engraved on the monument: No epitaph can express all the greatness of this name.

The Italian scientist and Renaissance thinker Niccolò Machiavelli has an ambivalent reputation. On the one hand, he is often quoted and given as an example of how a state should be run. And others consider him an extremely cynical adviser to the politicians of the past, the only measure of which is not morality, but power and money. In this article we will try to figure out who this man really was.

Childhood and youth

Not much is known about this period in the life of Niccolo Machiavelli, whose ideas we will characterize here. He was born in a small village, which was located on the territory of the then Republic of Florence. His father Bernardo was a famous lawyer. Education was given to him by home teachers, but at the same time Niccolo received excellent knowledge of ancient classical culture. He knew Latin and read such Roman authors as Titus Livius and Cicero in the original. At a young age history and politics topped his list of interests. He actively tried to interfere in the events of his native city-state, as evidenced by his correspondence with famous figures - for example, critical remarks about the activities of Savonarola in Florence.

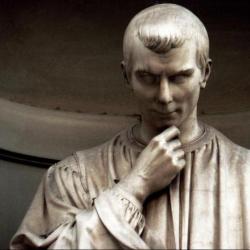

Niccolo Machiavelli - biography of a celebrity at the time of the beginning of a political career

Portraits and descriptions of the appearance of this figure of the Renaissance have been preserved. Biographers claim that he was thin, white-faced, black-haired, with a high forehead and thin lips. Many mention his sardonic smirk. The life of this man took shape at a very turbulent time for Florence, when many neighboring states, taking advantage of the political moment, tried to seize the Italian republics. There was no stable government, almost every month there were coups. Even then, Machiavelli Niccolo began to make a career using dubious methods. For example, on the one hand, in private letters he criticized Savonarola, but he took his first post in the public service with his support. And when the rigoristic monk was burned as a heretic, Machiavelli nevertheless was again re-elected to the authorities, this time due to the fact that the prime secretary of Florence, Marcello Adriani, was his teacher. The first ten years of the sixteenth century Niccolo makes diplomatic missions to different countries on behalf of the Republic.

Career heyday

In 1501, Machiavelli Niccolo reached such a standard of living that he was able to marry a representative of his social circle. The marriage was successful both economically and family-wise. The couple had five children, and besides, Niccolò also started friendly relations with various beauties abroad. In 1502, he met the famous adventurer and commander Cesare Borgia, who impressed him with his ability to use any chance that turned up to him to expand his own possessions. He spent a year in his service. It was then that he was seized by the idea of writing a treatise on an ideal ruler who could masterfully achieve his goals, regardless of morality. But when Pope Alexander Borgia, father of Cesare, died in 1503, the latter lost his financial means, and Niccolò was forced to return to Florence. He also served the Republic with some intrigues during a diplomatic mission in Rome, trying to influence the policy of the new Pope, and then dealt with the internal structure of the Republic and its defense capability. In particular, he is the author of the idea of a professional army (the treatise Dialogue on the Art of War). He successfully put this theory into practice in Florence, in connection with which the city-state regained the seceded Pisa.

Exile

The triumph of Machiavelli Niccolo continued until 1512. Pope Julius II was able to achieve the withdrawal of French troops from the Italian republics, who at the end of the fifteenth century expelled the famous Medici family from Florence, who had ruled the city for many decades. After that, the son of Lorenzo the Magnificent - Giovanni - returned to his fiefdom, liquidated the Republic and began to crack down on those who opposed his family. Machiavelli also suffered from these repressions, Niccolo, who was thrown into prison, accused of an anti-state conspiracy, and even tortured. But in the end, he managed to justify himself and went into exile, to the estate of his parents, where almost until the end of his days he lived with his family and wrote treatises that brought him worldwide fame. He led a measured existence, walking around the neighborhood and reading ancient authors. In 1520, Florence again returned to its diplomat a public position - this time, a historiographer. The famous figure died in 1527 on his estate, but no one knows where his grave is. His "History of Florence" enjoyed great success among compatriots, including after the death of the author.

Political views of Niccolo Machiavelli

They are difficult to characterize unambiguously. There was an opinion that the main thing for the scientist was cynicism, which allows him to achieve his goals by any means. There is some truth in this, but one should share Machiavelli's attitude towards the people, enemies and opponents. When Niccolo writes about the ideal ruler, he advises him to rely on the opinion of the population, improve his life and protect freedoms. He proposes a cynical policy of lies in relation to enemies, and he advises applying cruelty to those who encroach on power. But it was not only Niccolò Machiavelli who thought so in those days. His books on politics - "The Sovereign" and "Discourses on the First Decade of Titus Livius" became a compilation of the opinions of many famous people prevailing in the Renaissance, including those in power.

What is politics

In his writings, Machiavelli reveals the ins and outs of the relationship between rulers, people, institutions and laws, and also thinks about how to achieve a better functioning of the latter. He can be called the "father of political science" because he was the first to declare that it is an experiential science that can understand the past, guide the present and foresee the future. The scientist also believed that a lot depends on the personality of the sovereign. He was a supporter of strong power and a firm hand, stating that centralized government, based on force, and using morality only as a cover, is ultimately better for the people, and for the sake of the unity of the country, disunity can be suppressed. At the same time, he did not like the lower strata of the population. He considered prosperous and politically active citizens to be the people, whose opinions should be heeded. It is the reliance on such people, who are granted the greatest freedoms, that serves as the basis for the viability of the state.

How to take and keep power

What was Niccolò Machiavelli's favorite subject? His philosophy was to analyze the most practical ways to seize state power and the art of ruling, that is, to keep it as long as possible. The ideal for him were the ancient republics, which, in his opinion, combined the love of freedom and good laws. The main thing in the complex art of power is a good goal - the independence and greatness of one's own state. To achieve it, you can use any means. No morals or rights should stand in the way of the state, especially if it protects its own interests. The law should be respected as long as it suits the needs of the country. If, for the sake of observing the state interest or the prosperity of the country, it should be bypassed, then this must be done. Nevertheless, the philosopher does not hope too much for the seizure of power by force, since such a government will always have to be maintained with the help of weapons, and this is an unnecessary waste of strength. He preferred a hereditary monarchy.

How to manage

First of all, the head of state must take care that the population subject to him cannot harm him. There are two ways to do this - keep him in fear or shower him with favors. God does not play any role in whether the sovereign will be able to rule for a long time - it depends on fortune. It is better for a monarchy to be absolute. Otherwise, the ruler is always dependent on the will of the elected bodies, which will constantly hamper him. The sovereign must also remember that he is surrounded by enemies both inside and outside the country. Therefore, he should always be on the alert, be like a lion and a fox at the same time. This comparison has become the most popular of all examples given by Niccolò Machiavelli. Quotations of this kind, sometimes taken out of context, wandered from one political treatise to another. And the very political concept of the author was called Machiavellianism.

Literary and philosophical heritage

The works of the first political scientist of the Renaissance were initially criticized. First of all, the Roman Catholic Church disagreed with them. But not at all because of the principle proclaimed by the author that for the sake of a good end all means are permitted, but because he deprived the clergy of the exclusive right to moral guidance. Therefore, the works of Machiavelli were condemned at the church council in Trento and even included in the Index of Forbidden Books. On the other hand, many philosophers, like Jean Bodin or Thomas Hobbes, who defended the idea of a centralized state, considered him an innovator in political life, a man who dared to write the truth about what everyone has been doing for so long. Indeed, Machiavelli broke with the ideas of the Middle Ages that a person should serve God, including in the public service, and elevated power and its interests to the center. Politics has become an independent discipline, acting for practical purposes and justifying violations of laws and immoral acts for their sake.

MACHIAVELLI, NICCOLO(Machiavelli, Niccolo) (1469–1527), Italian writer and diplomat. Born May 3, 1469 in Florence, the second son in the family of a notary. Machiavelli's parents, although they belonged to an ancient Tuscan family, were people of very modest means. The boy grew up in the atmosphere of the "golden age" of Florence under the regime of Lorenzo de' Medici. Little is known about Machiavelli's childhood. From his writings it is clear that he was an astute observer of the political events of his time; the most significant of these was the invasion of Italy in 1494 by Charles VIII of France, the expulsion of the Medici family from Florence and the establishment of a republic, initially under the rule of Girolamo Savonarola.

In 1498, Machiavelli was hired as a secretary in the second office, the College of Ten and the magistracy of the Signoria - posts to which he was elected with constant success until 1512. Machiavelli devoted himself entirely to an ungrateful and poorly paid service. In 1506, he added to his many duties the work of organizing the Florentine militia (Ordinanza) and the Council of Nine, which controls its activities, established to a large extent at his insistence. Machiavelli believed that a civilian army should be created that could replace the mercenaries, who were one of the reasons for the military weakness of the Italian states. Throughout his service, Machiavelli was used for diplomatic and military assignments in the Florentine lands and for collecting information during foreign trips. For Florence, which continued the pro-French policy of Savonarola, it was a time of constant crises: Italy was torn apart by internal strife and suffered from foreign invasions.

Machiavelli was close to the head of the republic, the great Gonfalonier of Florence, Piero Soderini, and although he did not have the authority to negotiate and make decisions, the missions that were entrusted to him were often delicate and very important. Among them, embassies to several royal courts should be noted. In 1500, Machiavelli arrived at the court of King Louis XII of France to discuss the terms of assistance in continuing the war with the rebellious Pisa, which had fallen away from Florence. Twice he was at the court of Cesare Borgia, in Urbino and Imola (1502), in order to stay abreast of the actions of the Duke of Romagna, whose increased power worried the Florentines. In Rome in 1503 he oversaw the election of a new pope (Julia II), and while at the court of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I in 1507, he discussed the size of the Florentine tribute. Actively participated in many other events of that time.

During this "diplomatic" period of Machiavelli's life, he acquired experience and knowledge of political institutions and human psychology, on which - as well as on the study of the history of Florence and ancient Rome - his writings are based. In his reports and letters of that time, you can find most of the ideas that he subsequently developed and which he gave a more refined form. Machiavelli often felt a sense of bitterness, not so much because of familiarity with the downside of foreign policy, but because of the divisions in Florence itself and its indecisive policy towards powerful powers.

His own career faltered in 1512 when Florence was defeated by the Holy League formed by Julius II against the French in alliance with Spain. The Medici returned to power, and Machiavelli was forced to leave public service. He was followed, he was imprisoned on charges of conspiring against the Medici in 1513, he was tortured with a rope. In the end, Machiavelli retired to the modest estate of Albergaccio inherited from his father in Percussine near San Casciano on the way to Rome. Some time later, when Julius II died and Leo X took his place, the anger of the Medici softened. Machiavelli began to visit friends in the city; he took an active part in literary meetings and even cherished the hope of returning to the service (in 1520 he received the post of state historiographer, to which he was appointed by the University of Florence).

The shock experienced by Machiavelli after his dismissal and the collapse of the republic, which he served so faithfully and zealously, prompted him to take up his pen. The character did not allow long to remain inactive; Deprived of the opportunity to do what he loves - politics, Machiavelli wrote works of considerable literary and historical value during this period. Major masterpiece - Sovereign (Il Principe), a brilliant and well-known treatise, written mainly in 1513 (published posthumously in 1532). The author originally titled the book About principalities (De Principatibus) and dedicated it to Giuliano de' Medici, brother of Leo X, but he died in 1516, and the dedication was addressed to Lorenzo de' Medici (1492-1519). Historical work of Machiavelli Reflections on the first decade of Titus Livius (Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio) was written in the period 1513–1517. Among other works - Art of War (Dell "arte della guerra, 1521, written in 1519–1520), History of Florence (Historie fiorentine, was written in 1520-1525), two theatrical plays - Mandrake (Mandragola probably 1518; original title - Commedia di Gallimaco e di Lucrezia) And clicia(probably in 1524-1525), as well as a short story Belfagor(in the manuscript Fairy tale, written before 1520). He also wrote poetry. Although the debate about Machiavelli's identity and motives continues to this day, he is by far one of the greatest Italian writers.

It is difficult to assess the works of Machiavelli, primarily because of the complexity of his personality and the ambiguity of ideas, which still cause the most controversial interpretations. Before us is an intellectually gifted person, an unusually insightful observer who had a rare intuition. He was capable of deep feeling and devotion, exceptionally honest and industrious, and his writings reveal a love for the joys of life and a lively sense of humor, though usually bitter. Yet the name Machiavelli is often used as a synonym for betrayal, deceit and political immorality.

In part, such assessments are caused by religious reasons, the condemnation of his works by both Protestants and Catholics. The reason was the criticism of Christianity in general and the papacy in particular; according to Machiavelli, the papacy undermined military prowess and played a negative role, causing the fragmentation and humiliation of Italy. On top of that, his views were often distorted by commentators, and his phrases about establishing and protecting statehood were taken out of context and quoted in order to reinforce the common image of Machiavelli as a malicious adviser to sovereigns.

Besides, Sovereign was considered his most characteristic, if not the only work; from this book it is very easy to select passages that clearly prove the author's approval of despotism and are in striking contradiction with traditional moral norms. To some extent, this can be explained by the fact that Sovereign emergency measures are proposed in an emergency; however, Machiavelli's aversion to half-measures, as well as a craving for a spectacular presentation of ideas, also played a role; its oppositions lead to bold and unexpected generalizations. At the same time, he did consider politics to be an art that does not depend on morality and religion, at least when it comes to means rather than ends, and made himself vulnerable to accusations of cynicism, trying to find universal rules of political action that were would be based on observation of the actual behavior of people, and not reasoning about how it should be.

Machiavelli argued that such rules are found in history and confirmed by contemporary political events. In the dedication to Lorenzo de' Medici at the beginning Sovereign Machiavelli writes that the most valuable gift that could be offered is the comprehension of the deeds of great people, acquired by "many years of experience in the affairs of the present and the incessant study of the affairs of the past." Machiavelli uses history to reinforce, through carefully selected examples, the maxims of political action that he formulated from his own experience rather than historical studies.

Sovereign- the work of a dogmatist, not an empiricist; still less is it the work of a person applying for a position (as has often been assumed). This is not a cold call to despotism, but a book imbued with high feeling (despite the rational presentation), indignation and passion. Machiavelli seeks to show the difference between authoritarian and despotic modes of government. Emotions come to a head at the end of the treatise; the author appeals to a strong hand, the savior of Italy, the new sovereign, capable of creating a powerful state and freeing Italy from the foreign domination of the "barbarians".

Machiavelli's remarks about the need for ruthless solutions, if they seem dictated by the political situation of that era, remain relevant and widely debated in our time. Otherwise, his direct contribution to political theory is insignificant, although many of the thinker's ideas stimulated the development of later theories. The practical impact of his writings on statesmen is also doubtful, despite the fact that the latter often relied on the ideas of Machiavelli (often distorting them) about the priority of the interests of the state and the methods that a ruler should use in gaining (acquista) and retaining (mantiene) power. As a matter of fact, Machiavelli was read and quoted by adherents of autocracy; however, in practice, autocrats managed without the ideas of the Italian thinker.

These ideas were of greater importance for Italian nationalists during the era of the Risorgimento (political revival - from the first outbreaks of carbonari in the 20s of the 19th century to unification in 1870) and during the period of fascist rule. Machiavelli was mistakenly seen as the forerunner of the centralized Italian state. However, like most Italians of that time, he was not a patriot of the nation, but of his city-state.

In any case, it is dangerous to attribute to Machiavelli the ideas of other eras and thinkers. The study of his works should begin with the understanding that they arose in the context of the history of Italy, more specifically, the history of Florence in the era of wars of conquest. Sovereign was conceived as a textbook for autocrats, significant for all times. However, when considering it critically, one should not forget about the specific time of writing and the personality of the author. Reading the treatise in this light will help to understand some obscure passages. The fact remains, however, that Machiavelli's reasoning is not always consistent, and many of his apparent contradictions must be recognized as valid. Machiavelli recognizes both the freedom of a person and his "fortune", a fate that an energetic and strong person can still somehow fight. On the one hand, the thinker sees a hopelessly corrupted being in a person, and on the other hand, he passionately believes in the ability of a ruler endowed with virtu (perfect personality, valor, full strength, mind and will) to free Italy from foreign domination; defending human dignity, he at the same time gives evidence of the deepest depravity of man.

It should also be briefly mentioned reasoning, in which Machiavelli focuses on republican forms of government. The work claims to formulate the eternal laws of political science derived from the study of history, but it cannot be understood without taking into account the indignation caused by Machiavelli at the political corruption in Florence and the inability to rule of the Italian despots, who presented themselves as the best alternative to chaos, created by their predecessors in power. At the heart of all Machiavelli's works is the dream of a strong state, not necessarily republican, but based on the support of the people and capable of resisting foreign invasion.

Main Topics Stories of Florence(whose eight books were presented to Pope Clement VII of the Medici in 1525): the need for general consent to strengthen the state and its inevitable decomposition with the growth of political strife. Machiavelli cites facts described in historical chronicles, but seeks to reveal the true causes of historical events, rooted in the psychology of specific people and the conflict of class interests; he needed history in order to learn lessons that he believed would be useful for all time. Machiavelli, apparently, was the first to propose the concept of historical cycles.

History of Florence, characterized by a dramatic narrative, tells the story of the city-state from the birth of the Italian medieval civilization to the beginning of the French invasions at the end of the 15th century. This work is imbued with the spirit of patriotism and determination to find rational, and not supernatural, causes of historical events. However, the author belongs to his time, and references to signs and wonders can be found in this work.

Machiavelli's correspondence is of extraordinary value; especially interesting are the letters he wrote to his friend Francesco Vettori, mainly in 1513-1514, when he was in Rome. You can find everything in these letters - from descriptions of the minutiae of domestic life to obscene anecdotes and political analysis. The most famous letter is dated December 10, 1513, which depicts an ordinary day in the life of Machiavelli and gives an invaluable explanation of how the idea came about. Sovereign. The letters reflect not only the ambitions and anxieties of the author, but also the liveliness, humor and sharpness of his thinking.

These qualities are present in all his writings, serious and comedic (for example, in mandrake). Opinion differs on the stage value of this play (it is still sometimes performed, and not without success) and the evil satire it contains. However, Machiavelli also carries out some of his ideas here - about the success that accompanies determination, and the inevitable collapse that awaits the hesitant and those who wishful thinking. Her characters - including one of the most famous simpletons in literature, the deceived Messer Nitsch - are recognizable as typical characters, although they give the impression of the results of original creativity. The comedy is based on living Florentine life, its manners and customs.

The genius of Machiavelli also created fiction Biography of Castruccio Castracani of Lucca, compiled in 1520 and depicting the rise to power of the famous condottiere at the beginning of the 14th century. In 1520 Machiavelli visited Lucca as a trade representative on behalf of Cardinal Lorenzo Strozzi (to whom he dedicated the dialogue On the art of war) and, as usual, studied the political institutions and history of the city. One of the fruits of his stay in Lucca was Biography, depicting a ruthless ruler and famous for its romantic exposition of ideas about the art of war. In this small work, the author's style is as refined and bright as in other works of the writer.

By the time Machiavelli created the main works, humanism in Italy had already passed the peak of its heyday. The influence of the humanists is noticeable in the style Sovereign; in this political work, we can see the interest characteristic of the entire Renaissance not in God, but in man, personality. However, intellectually and emotionally, Machiavelli was far from the philosophical and religious interests of the humanists, their abstract, essentially medieval approach to politics. Machiavelli's language is different from that of the humanists; the problems he discusses hardly occupied humanistic thought.

Machiavelli is often compared to his contemporary Francesco Guicciardini (1483–1540), also a diplomat and historian immersed in political theory and practice. Far from being as aristocratic in birth and temperament, Machiavelli shared many of the basic ideas and emotions of the humanist philosopher. Both of them are characterized by a sense of the catastrophe in Italian history due to the French invasion and indignation at the state of fragmentation that did not allow Italy to resist subjugation. However, the differences and discrepancies between them are also significant. Guicciardini criticized Machiavelli for his persistent appeal to modern rulers to follow ancient models; he believed in the role of compromise in politics. In essence, his views are more realistic and cynical than those of Machiavelli.

Machiavelli's hopes for the heyday of Florence and his own career were deceived. In 1527, after Rome was given to the Spaniards for plunder, which once again showed the full extent of the fall of Italy, republican rule was restored in Florence, which lasted three years. The dream of Machiavelli, who returned from the front, to get the position of secretary of the College of Ten did not come true. The new government did not notice him anymore. The spirit of Machiavelli was broken, his health was undermined, and the life of the thinker ended in Florence on June 22, 1527.

Creativity and personality (1469-1512) constantly aroused interest among political scientists and researchers. A prominent political figure of the late Italian Renaissance, Machiavelli held a high position in the administration of the Florentine Republic, being Secretary of the Senoria, Chancellor of the Ten. The occupation of this position was preceded by the experience of solving legal cases in high instances. Machiavelli was the organizer and participant of the military company and the initiator of the creation of the republican militia.

The political worldview of Machiavelli took shape in the conditions of the death of the republic and the first steps of absolutism. That is why the way of thinking and the personality of a politician of the late Renaissance were so contradictory. Considering the republic as the best form of state, Machiavelli is gradually inclined to the idea that in order to unite Italy and protect it from external enemies, a strong, unlimited, "emergency power" is needed - the dictatorship of the sovereign.

The prototype of the ideal ruler for Machiavelli was Caesar Borgia - Duke Valentino - a cruel, decisive and shrewd ruler who does not take into account morality. Scholars of Machiavelli's legacy have accused him of introducing immorality into the principle of politics, and one of the purposes of this essay is to prove that Machiavelli did not idealize authoritarian rule, but rather explored the essence of autocracy and the methods for establishing it.

Machiavelli and his political ideas attracted attention as early as the 16th century. And if, as a writer and author of the play "Mandrake", he was recognized above Boccaccio, then the fate of his political studies was sad: many of his books were banned, the Inquisition tortured them for their possession. However, the interest in his works and their interpretation were so great that they led to the spread of the opinion about Machiavelli as a preacher of the method of permissiveness in politics, justifying any immoral act of the ruler, an apologist for the idea "the end justifies the means."

Modern political science is based on the experience of researchers of Machiavelli's work. One of the first Russian researchers of the political heritage of the great Italian was A.S. Alekseev. He was the first of the domestic researchers of the great Florentine’s work to note that not all of the views attributed to him corresponded to the meaning of his teachings: “A whole series of Machiavelli’s thoughts, most clearly illuminating his political convictions and the philosophical lining of his teachings, either remained unnoticed to this day, or were falsely interpreted "(Alekseev A.S. Machiavelli as a political thinker. M, 1890, p. U1).

The monograph by V. Topor-Rabchinsky “Machiavelli and the Renaissance” shows how mercilessly he criticizes the cunning and cruelty of tyrants, how he is looking for the ideal type of sovereign who would establish justice, order and independence from strangers.

Research by V.I. Rutenburg's "The Life and Work of Machiavelli" (L., 1973) most fully expresses the modern point of view on the controversial work of a political thinker, proves that much of what "Machiavellianism" has grown out of was conjectured for him by later followers.

The starting point in Machiavelli's teaching about the best structure of modern society is the principle of a realistic assessment of reality. Not God and not fortune, in his opinion, but only a deep sober analysis of circumstances and the ability to restructure actions in accordance with the real situation can ensure the ruler's success in all his endeavors. This thought permeates all the political recommendations of Machiavelli. The basis for this is not only ancient history, examples of which are widely used in his writings, but also Italian reality itself. The study of the life situation, specific circumstances should determine the actions of people if they strive for happiness and well-being. Even fate cannot violate this principle, because its capabilities are equal to those of a person: “I believe that it is very possible that fate controls half of our actions, but at the same time I think that it leaves at least the other half to our will.” Machiavelli is alien to prejudice, but suggests believing in fate. He really recognizes the power of fate (fortuna), more precisely, the circumstances that force a person to reckon with the power of necessity (necessita). But fate, according to Machiavelli, has only half power over a person, influencing his actions, the course and outcome of events. A person can and must struggle with the circumstances surrounding him, with fate, and the second half of the matter depends on human energy, skill, and talent. Concluding his discussions about the role of fate in human life, Machiavelli emphasizes the importance of assessing circumstances: “With the variability of fate and the constancy of the way people act, they can be happy only as long as their actions correspond to the circumstances surrounding them; but as soon as this is violated, people immediately become unhappy.

So, let's try to figure out what led Niccolo Machiavelli, a prominent figure in the republican Florence, to the conclusion and open propaganda of a one-man form of government. As mentioned above, based on historical experience from ancient times to the present, Machiavelli analyzed the structure of the Italian states and, as a realistic politician of an unconditionally republican persuasion, tried to establish the general laws of political life. He comes to the conclusion that the main law of political life is the constant change in the forms of government: "... various types of governments are born, which can go through many times repeated changes." The experience of modern Italian states leads him to the idea that "the principate easily becomes a tyrannical form of government, the power of the optimates easily becomes the rule of a few, and the people easily incline to free behavior." The law of cyclism of forms of government derived by Machiavelli asserts: the historical process, the change in the forms of the state does not occur at the request of people, but under the influence of immutable life circumstances, under "the influence of the actual course of things, and not imagination."

Machiavelli was the first of the Renaissance thinkers, a thinker of a new type, who proclaimed the natural necessity of changing forms of government. “If the idea of a vicious circle of the historical process was consonant with the conditions of late Renaissance Italy, Machiavelli’s thesis about the inevitable movement and even dialectical outgrowth (literally “slipping”) of various forms of the state into its opposite, regardless of virtuous or vicious means, turned out to be more fruitful and promising. (Rutenburg, p. 368)

One of the characteristic features of the Italian Renaissance was a realistic attitude to reality, and this feature is fully characteristic of the work of Niccolo Machiavelli. As a progressive politician of his era, Machiavelli dreamed of the reunification of Italy into a single state, free from the dictates of the papacy and the willfulness of foreigners. In his opinion, the only way to achieve this goal is to establish a firm government. In fact, this is what The Sovereign is dedicated to, the last chapter of which calls in a general form to fight for the elimination of the rule of foreign barbarians and the salvation of Italy.

Machiavelli gives a clear definition of the causes of Italy's weakness - he considers the papacy to be the culprit of the political fragmentation of the country. Recognizing religion as a tool to strengthen the state, Machiavelli nevertheless notes that the cause of the collapse is the church, "it was the church that kept and keeps our country divided."

It is hardly possible to consider The Sovereign as a manual for the unification of the country - political and economic prerequisites will allow this to be done only three centuries later - but from written works it can be assumed that Machiavelli envisaged the unification of Italy in the form of a confederation. “The experience of history, Machiavelli’s own observation of the political life and forms of government of France, the papacy, the German lands, the signories and the republics of Italy, obviously convinced him of the unreality of the commonwealth of individual Italian states and the need for a firm power of well-organized republics” (Rutenburg, p. 368) Ideal Machiavelli had a republican-signorial rule, exemplified by the periods of "mixed rule" of Lycurgus in Sparta and Roman models. The activities of Caesar Borgia, Francesco Sforza, the Medici, the Venetian patricians, led by the Doge, made it possible to summarize the experience of the Italian tyranny of the 15th century: “... who fights to rule the people, whether through the republican or through the principate, and does not worry that there are enemies of the new building, forms a very short-lived state. (Machiavelli, "The Sovereign", p. 47).

Every person, and even more so a sovereign, must act depending on what requirements reality puts forward. The activities of the sovereign must be analyzed in connection with specific circumstances, because its success depends on this. It is in the name of the principle of conformity of actions to the requirements of the time that Machiavelli admits the possibility of a sovereign’s violation of ethical norms: “Sovereigns must have a flexible ability to change their beliefs according to the circumstances and, as I said above, if it is possible not to avoid the honest path, but if necessary, resort to dishonorable means” . (Ch. XY111).

The ruler must adhere to the principle of firm power, use any means to strengthen the state and, if necessary, show cruelty. Consistently pursuing this principle, Machiavelli comes to the justification of immorality - if one ignores the purpose for which he sanctions the immorality of the sovereign. And this goal is the well-being of the state, and in the conditions of Italy - the creation of a strong unified political power. With this, Machiavelli, as it were, brings high politics down to real earthly soil.

Machiavelli shared the belief of most humanists in the creative possibilities of man. Deprived of any abstractness, his faith has a practical purposefulness. The ideal of man is embodied by Machiavelli in the image of a strong, politically active personality, capable of creating a well-ordered state, where the interests of the people and the actions of the ruler are in full harmony. Society needs a strong personality, and therefore her actions should be directed to the common good: “it is necessary that the will of one give the state its order and that the individual mind manage all its institutions ... No intelligent person will reproach him if, during the arrangement state, or when establishing a republic, he will resort to some emergency measures. (Machiavelli, soch, vol. 1, p. 148, M., 1934).