The Grand Duchy of Lithuania in brief. Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Russian Lithuanians at the monument to the “Millennium of Russia”

Class: 6

Presentation for the lesson

Back forward

Back forward

Attention! Slide previews are for informational purposes only and may not represent all the features of the presentation. If you are interested in this work, please download the full version.

Lesson objectives.

Educational:

- Form an idea of the Russian-Lithuanian state;

- Describe the reasons for the formation of the Principality of Lithuania;

- Understand the political structure of the Lithuanian-Russian state and the religious policy of its first princes;

- Show the consequences of the annexation of Russian lands to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania;

Educational:

- Continue to work on developing the skills to independently extract information about the course of historical events from a map.

- Work on developing oral speech;

- Develop skills in working with a textbook and additional material, the ability to compare, highlight the main thing, generalize, and draw conclusions.

Educational:

- Formation of interest in history;

- Foster respect for the traditions and historical past of your homeland.

- Contribute to the moral education of students.

Basic concepts of the lesson: Lithuanian-Russian state - Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Vilna - a multinational city, the capital of different cultures, religions and traditions, Gediminovichi, Olgerdovichi.

Successive connections.

- Intrasubject: 6th grade Middle Ages - Formation of centralized states in Europe

Means of education: presentation "Rus and Lithuania"

DURING THE CLASSES

1. Organizational moment.

2. Communicate the topic and objectives of the lesson.

3. Survey on homework and previously studied material.

I. Survey:

Oral blitz survey (frontal).

"Knowledge Auction".

1). What period of the history of Ancient Rus' are we studying?

- "Rus in the second half of the 12th - 13th centuries."

2). What, what main events characterize this period?

The fragmentation of the Old Russian state, in history this period is called “feudal fragmentation” - and this is a natural process of isolation of individual lands led by princes claiming political independence.

3). What are the causes of feudal fragmentation?

Civil strife;

The order of governance in the Old Russian state;

Order of succession;

Undermining the defense capability of the Old Russian state;

The decline of the Kyiv land from the raids of the steppe inhabitants (Polovtsians).

4). List the largest principalities formed as a result of feudal fragmentation?

Kiev, Chernigov, Novgorod, Vladimir-Suzdal, Galicia-Volyn.

5). What events take place at the beginning of the 13th century?

At the beginning of the 13th century. Mongol tribes led by Genghis Khan invade the Polovtsian steppe.

On May 31, 1223, the battle takes place on the river. Kalke. The Russian army was defeated, and the Mongols, having suffered a series of defeats on the Volga, returned back.

6). When did Khan Batu begin his campaign against Rus'? What are the consequences of Batu's invasion of Rus'?

Batu Khan began his campaign against Rus' in 1236.

1237 - the Ryazan principality was subjected to the first blow, the city of Ryazan was wiped off the face of the earth.

Then they were devastated: Vladimir, Torzhok, Kozelsk (Batu called Kozelsk an “evil city”);

1240 - Kiev.

7). What other test did the Russian people have to endure simultaneously with the Mongol invasion?

Rus' had to fight with Western conquerors: Germans, Swedes.

8). In what year did the battle take place for which Alexander Yaroslavovich, Prince of Novgorod, was nicknamed Nevsky?

July 15, 1240 - Prince Alexander and the Russian army won a brilliant victory on the Neva, for which the people nicknamed Alexander Yaroslavich NEVSKY.

9). What battle went down in history as the Battle of the Ice?

April 5, 1242 - the battle on the ice of Lake Peipsi went down in history as the Battle of the Ice

Thus, as a result of the battles on the Neva and Lake Peipus, an attack on Rus' by its northwestern neighbors was repulsed.

10). What is a shortcut?

This is a special khan’s charter for reign, which gave the Russian prince the right to rule in his lands. In 1243, Batu Khan became the ruler of his own state. In Rus' this state was called the GOLDEN HORDE. The city of Saray became its capital. Russian people called the inhabitants of the Golden Horde Horde or Tatars. The Russian lands did not become part of the Golden Horde, but fell into vassal dependence on it. The ancient Russian traditions of inheriting principalities continued to operate in Rus', but the Horde government brought them under its control.

eleven). What was the name of the regular tribute that was collected in Rus' for the Khan of the Golden Horde?

Annual payments to the Horde, called in Rus' - exit, or Horde tribute.

12). What were the names of the khan's governors sent to Russian cities to oversee the collection of tribute and its sending to the Horde?

They were called BASKAKI, who, relying on armed detachments, made sure that the population regularly paid tribute.

Summing up the survey:

Thus, Rus' in the second half of the XII - XIII centuries. characterized by:

Feudal fragmentation;

The allocation of such large principalities as Vladimir-Suzdal, Novgorod, Galicia-Volyn;

Also the invasion of Mongol tribes in Rus';

As a result of the Mongol invasion, Rus' fell under Horde rule, which had both economic, political and cultural consequences.

Rus' had to go through another test - the fight against Western conquerors (Germans, Swedes);

4. STUDYING NEW MATERIAL.

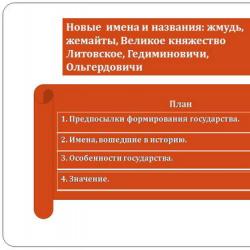

Plan.

1) Formation of the Lithuanian-Russian state.

2) Names that went down in history.

3) Features of the state of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

4) The significance of the annexation of Russian lands to Lithuania.

The consolidation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania took place against the background of resistance to the crusaders of the Teutonic Order in Prussia and the Order of the Sword in Livonia. The turbulent events of the late 1230s - early 1240s (Mongol invasion, expansion of the Crusaders) do not allow us to accurately establish the details of the formation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. We can definitely say that by 1244-1246 the Grand Duchy of Lithuania already existed as a state headed by Mindaugas, who had the title of Grand Duke of Lithuania. Working with the map.

Students begin to fill out the table.

II. Formation of the Lithuanian-Russian state.

The Western lands of Rus', protected from the Horde horsemen by the possessions of their neighbors, forests and swamps, managed to avoid the invasion of Batu, while North-Eastern Rus' was defeated by the Mongols.

The neighbors of Western Rus' were the Lithuanian tribes. By the beginning of the 13th century. to resist the invaders, they united and created a state led by Prince MINDOVG (1230-1264), a brave, cruel, treacherous ruler. He was supported by the Russian nobility of Grodno, Pinsk, Berestya and other lands of Western Rus'.

From that moment on, this new state was Russian-Lithuanian.

The Russian-Lithuanian lands united in order to jointly resist the most dangerous enemies who threatened both from the west and the east.

Mindovg appointed his eldest son VOYSHELK to rule the Russian lands. But soon Voishelk was baptized according to the Orthodox rite, became a monk, and transferred power to the Russian prince Roman Danilovich.

Mindaugas, hoping to stop the onslaught of knightly orders, agreed to convert to Catholicism, but the alliance with Rome did not live up to the hopes of the Lithuanian prince and in 1261 he renounced Christianity.

In 1263, Mindovg, along with his two younger sons, was killed during strife among the Lithuanian nobility.

With the help of Russian troops, the Orthodox Lithuanian prince-monk Voishelk established himself in the Lithuanian and Russian lands, but in 1267 he was treacherously killed.

III. The Lithuanian-Russian state reached its peak under Gediminas.

Having annexed the western territories of Rus', Gedimin turned his attention to the ancient capital of the Russian state of Kyiv, which, after the Horde raids, fell into complete decline, as a result in the late 20s - early. In the 30s of the 14th century, the Principality of Kiev recognized the power of Gediminas

By annexing Russian lands, Gediminas expanded the borders of his state far to the south and east. It became known as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

The establishment of the power of the Lithuanian princes was relatively peaceful, since the conditions for the annexation of Russian lands to the Lithuanian state satisfied both the boyars, the townspeople, and even the church.

IV. The character of the Lithuanian-Russian state.

The state of Gediminas resembled Rus' during the times of the first Russian princes. The lands retained their customs and traditions, the previous order of governance. Gedimin replaced only the rulers, placing his relatives, the Gedimins, on local thrones.

Some of them converted to Orthodoxy. The princes - governors collected and paid tribute to the Grand Duke of Lithuania. The Russian population viewed it as payment to the Lithuanian prince for protection from foreign attacks.

Under Gediminas, the city of Vilna, which he founded, became the capital of the state.

The first Catholic monasteries appeared here. The influx of population from Western European countries has increased.

Representatives of many cultures and traditions got along with each other here.

In European states, Gediminas was called the “King of Lithuania and Rus'.”

Gediminas, while remaining a pagan, did not infringe on the rights of the Orthodox Church.

At the same time, he established contacts with the Catholic Church, even promised the pope to baptize Lithuania according to the Western rite if the Crusader invasion ended.

1324 - the papal embassy arrived in Lithuania, but both the pagan Lithuanian nobility and the Russian Orthodox population opposed the introduction of Catholicism, Gediminas could not help but take them into account.

Dying, Gedimin divided his possessions between his sons.

Olgerd - the son of the Russian princess Olga - received the eastern part of the state, where Russian lands predominated. He continued his father’s policy of “gathering” Russian lands. The Bryansk, Seversk, Chernigov and Podolsk lands were annexed. Volyn was also assigned to Lithuania.

In 1377, after the death of Olgerd, new strife began in the principality, as a result of which Olgerd’s son Jagiello and Vytautas came to power.

To summarize all that has been said, we need to determine what is the significance of the annexation of Russian lands to Lithuania?

/problem-cognitive task/

Students read the text independently on page 125 (3 min.)

So let's define:

What is the significance of the annexation of Russian lands to Lithuania?

The affiliation had a positive meaning;

The Russian principalities were freed from the yoke of the Horde;

Through joint efforts it was possible to counter the threat from both the east and the west;

The high culture of the Russian lands and rich state experience had a positive impact on Lithuanian culture and statehood;

The Lithuanian people sought cooperation with the population of Russian lands;

Russian language became the official language of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania;

Thus, by annexing the western and southwestern lands of Rus', protecting them from Horde rule, Lithuania could become a center of attraction for its northeastern and northwestern lands.

Teacher: So, to summarize, we can say that in the XIII - XIV centuries the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was formed and reached its peak.

The peculiarity of this state was that both Lithuanians and Russians lived on its territory; that the political and cultural traditions of Rus' had a strong influence on the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

5. QUESTIONS TO REINFORM NEW MATERIAL:

What tribes were the neighbors of Western Rus'? (Lithuanian tribes)

What name did the prince who became the head of the Principality of Lithuania have? (Mindovg 1230-1264)

What was the name of the new state? (Russian-Lithuanian)

What was the purpose of uniting Russian and Lithuanian lands? (to jointly resist the most dangerous enemies who threatened both from the west and the east);

Under whom did the Lithuanian-Russian state reach its peak? (under Gediminas)

What are the characteristic features of the Lithuanian-Russian state? (- the Russian lands retained their customs and traditions; - they collected and paid tribute to the Grand Duke of Lithuania, and also considered it as payment to the Lithuanian prince for protection from foreign attacks and maintaining peace);

Which city became the capital? (city of Vilno);

Was the papal embassy able to baptize Lithuania according to the Western model? (- no, because both the pagan Lithuanian nobility and the Russian Orthodox population were against);

Who became the head of the eastern part of the state after the death of Gediminas? (his son is Olgerd);

After the death of Olgerd, who came to power? (- son of Olgerd - Jagiello, nephew - Vitovt).

6. REFLECTION.

1). I learned in class _________________________________

2). I realized that ___________________________

3). I think that _______________________________

7. SUMMARY.

Today in class we worked actively:

8. HOMEWORK- paragraph 15, tasks in the workbook for paragraph 15.

Sources used.

1. Danilov A.A. Russian history. From ancient times to the end of the 16th century. 6th grade. M.: Education, 2007.

2. Danilov A.A., Kosulina L.G. History of Russia from ancient times to the end of the 16th century. 6th grade. Workbook. M.: Education, 2007.

3. Serov B.N., Garkusha L.M. Lesson studies on the history of Russia from ancient times to the end of the 16th century. M.: "VAKO", 2004.

4. http://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki

5. http://www.grodno.by/grodno/history/biblio/vitovt.html

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania in some historical works is called the Russian-Lithuanian state; it existed from the second third of the 13th century to 1795 on the territory of most CIS countries and combined a huge number of peoples differing from each other in origin, religion and social status. It would seem that this political unit would exist for a long time, but after the division of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth it sank into oblivion.

How did the principality appear?

Historians note that the prerequisites for the formation of the Lithuanian-Russian state appeared at the beginning of the 11th century, and it was then that the first mentions of Lithuania appeared in the chronicles. In the 12th century they began to rapidly lose their positions; life inside these formations is not even described in historical papers. The only mentions in the chronicles are found only in connection with the numerous battles that took place then between the Russians and Lithuanians.

In 1219, agreements were signed on the formation of a joint state between representatives of the Galician-Volyn principality and various ethnic groups belonging to Lithuania. The eldest among all the princes, Mindovg, was mentioned as the ruler; it was he who controlled the consolidation of the newly formed country, which took place against the backdrop of resistance to the raids of the Mongols and crusaders. There is no exact date for the appearance of this state, but most researchers believe that it appeared in the 1240s after Mindovg began to rule Novogrudok, the center of the principality.

The new ruler understood the importance of cooperation with the church, which is why he became a Catholic in 1251. The Pope inaugurated Mindaugas as a full-fledged king, after which the formation of the Russian-Lithuanian state was carried out according to standard European rules. According to some reports, the coronation took place in Novogrudok, the capital of the new political entity. In parallel with the solution of administrative issues, active work was carried out to expand the territories in the northern and eastern directions.

Mindaugas made a large number of successful raids on Poland, thereby provoking the wrath of the church. The Poles, Austrians and Czechs repeatedly carried out Crusades against Lithuania, which led to the 1260s. Livonia, Poland and Prussia in 1260-1262 were repeatedly subjected to devastating and ruinous attacks by Mindaugas and his troops. A year later, the Supreme Prince was killed as a result of a conspiracy between the Polotsk and Nalshan rulers. Further, power constantly changed hands between various noble families.

Who lived in this country?

Initially, it was multinational, since it included a large number of lands with very different ethnic compositions. Most of the population consisted of Balts and Slavs, the latter coming from the former Russian principalities, which at one time were annexed by the Lithuanians. Subsequently, the Balts formed the Lithuanian people, and the Slavs formed the Ukrainian and Belarusian people, respectively.

The principality was also home to Poles, Prussians, Germans, Jews, Armenians, Italians, Hungarians and representatives of nations little known today. Despite the fact that all operations were conducted using the Western Russian language, it was not recognized as official for a long time; this only happened in the 14th century. In the middle of the 17th century, the Polish language was chosen for office work, but they tried not to use Lithuanian in official papers.

Historians from Lithuania, who spent a lot of time searching for an answer to the question of how the Russian-Lithuanian state was formed, claim that their language was a means of communication between representatives of various classes. Belarusian scientists do not agree with them; they argue that Lithuanian was used only for communication between the lower strata of society. There is no single point of view on this issue yet, but the fact of the use of all the above languages is confirmed by historical documents.

How was the state governed?

The structure of the Lithuanian-Russian state largely borrowed management techniques used in neighboring countries. All power was concentrated in the hands of the Grand Duke; the feudal lords who controlled the existence of smaller principalities and lands were subordinate to him. The ruler had the opportunity to conduct international affairs, make decisions about declaring peace or war, control troops and join various associations. All legislative documents were signed by the prince and only then came into force.

In the 15th-16th centuries, under the princes, there was a Rada, consisting of chancellors, governors, elders, bishops and other rich gentlemen with state administrative posts. It was understood that it would play the role of an advisory body, but over time it began to influence the power of the prince, which not everyone was happy with, including the rulers themselves.

If you suddenly have to take a history exam and are asked to emphasize statements characterizing the Lithuanian-Russian state, be sure to indicate the presence of the oldest lords of the council in the governing bodies of the country. This title could be given to bishops, governors, castellans and elders; it was they who carried out most of the work in conducting state affairs. They were involved in preparing decrees and their implementation, receiving foreign guests and conducting various audits and events.

The lords of the council exerted enormous influence during meetings devoted to the conduct of military operations. They most often advocated a position of peace between states and principalities, which is why they were often criticized by experienced commanders who viewed armed conflicts as a way to gain new lands and enrich their country.

Voytas, mayors and city councils acted as representatives of local authorities. The first served as governor for life; he was appointed by the prince himself, and he could not leave his post on his own. Members of the council were elected by the voit on the basis of letters received from the capital; its members included artisans and merchants. Through joint efforts, mayors were then elected, whose powers extended to urban improvement, solving current problems, shaping trade conditions, etc.

The head of the city controlled the timely collection of tax taxes, monitored the situation on his territory, and in some cases even administered justice. In populated areas, townspeople's gatherings were periodically held, at which mayors reported on expenditures from the treasury, accepted petitions and complaints, and also formed financial requests for certain events. At these gatherings, investigations of criminal cases were also carried out, and it was often there that decisions were immediately made. The larger the cities within the principality became, the more social inequality increased, which ultimately negated the need for holding meetings.

How was justice administered?

Until the 16th century, the legal system of the Russian-Lithuanian state was based on the “Russian Truth” - a code of laws created in 1468. In parallel with this, feudal practices and corresponding customs were used in the regions. In 1529, the first edition of the Statute was created - a systematic collection of legislative acts. Over the course of sixty years, it was rewritten several times, and only in 1588 was it possible to accept its final version. The latter operated even after the collapse of the state in those territories that were part of it until 1840.

Most of the ships that existed at that time were class-based, and were assembled as needed. This was especially true for cop courts, where the victim independently gathered local residents to determine the culprits and deal with the civil offense. Despite the democratic nature of the consideration of such cases, the authorities had to monitor the observance of order.

As one of the features of the Lithuanian-Russian state, one should highlight the transfer of state estates for maintenance to merchants and governors. The latter, although they had different incomes, had to pay a certain tribute to the prince, and by the 15th century such a scheme began to resemble a sale. Estates could be distributed for a certain period or until the will of the sovereign was revoked, but most often they were given for life. If the governor died, then the Grand Duke most often transferred the territory to his heir.

In the middle of the 16th century, zemstvo, sub-comorian and city courts appeared, which consisted of local representatives of the nobility with the necessary knowledge in the field of law. The jurisdiction of these institutions included civil and criminal cases, land disputes, as well as security for transactions and previously adopted court decisions. All procedures were in accordance with the then current Statutes.

In the Russian-Lithuanian state there were settlements that actively applied Magdeburg law, which came to the country from Poland. Its essence was to exempt residents from taxation and various duties; at the same time, it was proposed to relieve them of jurisdiction - if they did not commit a serious crime, then it would not be considered by government officials. It was far from being fully implemented, and the authorities did not allow complete self-government in the cities.

In those settlements where Magdeburg law was implemented, colleges of radts and lavniks were formed. The first had to conduct trials in civil cases, and the second had to consider criminal cases in the presence of the Vojt. Historical evidence proves that the existing order was very often violated: the voit could lead the council, and in some cases two boards were united into a magistrate for joint decision-making.

How did ordinary people live?

If someone asks you the question: “Name the characteristic features of the Lithuanian-Russian state,” remember, one of the correct answers will be the complete absence of serfdom right up to the middle of the 15th century. Until this moment, the labor force on the estates of noble people was taxation and unwitting servants; when there were not enough people, burghers and peasants who did not obey anyone were also called to help. The development of various branches of the economy rested with beekeepers, falconers, kennels and other classes of peasants. Craftsmen and tributaries were higher in status than tax collectors, although they also had to pay tribute.

Taxes were levied on arable lands and lands located on private or public territories: lakes and forests. They were not the same in size, and very often belonged to noble families, whose representatives carried out public service. The government made every effort to transfer taxation to the individual, as a result of which the peasants, one way or another, found themselves attached to certain plots of land, and not always to their own.

If an ordinary person became impoverished for some reason, he could move to another site or even ask a noble person to serve; the authorities practically did not return them to their own places. With all this, the rights of peasants to own land extended only to each other and persons from other social strata. The Supreme Prince had a unique right in the Russian-Lithuanian state; a briefly thrown word was enough to take away the land from any peasant without its further return.

The work of civilians was controlled by peasant authorities, consisting of the most experienced and responsible relatives. Most of the tribute that they had to give was taken in the form of oats, chickens, eggs, livestock, it could also be given in honey, fish, coal, and valuable furs. As a result, the peasants received only a small part of the products, which led to discontent among the population. The agrarian reform caused particular irritation among the residents of the principality, as a result of which the total amount of taxes increased by 1.5 times.

At the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th centuries, the Russian-Lithuanian state turned into a large arena for long and fierce battles. Hunger, epidemic and devastation flooded the country, the number of its inhabitants decreased by 50%, villages were plundered and burned as a result of peasant uprisings. Only such behavior of the country's inhabitants forced the government to temporarily release them from the exorbitantly high tribute.

In the middle of the 18th century, agriculture was restored to its previous level, which the landowners did not fail to take advantage of: they again began to increase taxes. In response to this, the peasants refused to do their work, organized escapes, and filed complaints in the courts. The process of rebuilding the country was constantly accompanied by skirmishes and conflicts, but they were less local and bloody.

What parts was the country divided into?

The structure of the Lithuanian-Russian state occurred throughout its entire existence. In the 12th century, it consisted of uniting nearby principalities and forming a single center of power, which required a lot of effort from all rulers. In the XIII-XIV centuries, after fierce battles, some territories belonging to Western Rus' became part of the state. In the 15th century, the country had a new capital - Vilna, at that time the area of the principality almost reached a million square kilometers.

The beginning of the 15th century was marked by a series of changes in the structure of the Lithuanian-Russian state; it is difficult to describe them briefly even for the most experienced historian. Within the principality, voivodeships appeared as large administrative units, and within them povets, consisting of several volosts, were formed. The division of the country took place over several years, and the process was not always peaceful.

It was only at the beginning of the 16th century that the creation of voivodeships was completed, and the rights of a large number of people were seriously violated. This was the reason for a completely new administrative reform in 1565, as a result of which 11 territorial administrative units were formed, which included Minsk, Vitebsk, Novgorod and Kiev voivodeships. The established order lasted from 1588 until the collapse of the principality.

What was the military power of the state?

From the very moment of its emergence, the Lithuanian-Russian state needed a professional army. Initially, military operations were carried out by armed groups consisting of boyars, but they were ineffective against the Polish princes and crusaders, who had extensive experience. Until the end of the 14th century, each boyar had his own squad with infantry and cavalry, consisting of 300 or more squires, footmen and archers. Such military formations were the main striking force that could fight battles with more or less variable success.

Since the 14th-16th centuries were a time of constant military action for the state, the supreme princes understood that a combat-ready army could help protect the country and not give it up to the enemy for plunder. As a result, military service became mandatory for absolutely every male representative, regardless of his class. At the end of the 14th century, a practice arose when, when attacked by enemy troops, a people's militia was immediately formed, capable of fighting back.

From the point of view of military affairs, the description of the Lithuanian-Russian state is a typical description of a European country in the Middle Ages. In the 16th century, the principality acquired several types of cavalry, cavalry and professional infantry appeared in its troops. The authorities even began to resort to using mercenaries - immigrants from other countries and local impoverished peasants who had been engaged in military affairs all their lives and defended the state from enemy machinations.

Did the people have aesthetic aspirations?

One of the main features of the Lithuanian-Russian state is that its culture was almost completely dissolved in the heritage of neighboring European and East Slavic states. Its creation was seriously influenced by the political and socio-economic factors of the surrounding countries; as a result, a certain metaculture emerged, which today can be seen in the behavior of Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians. The Principality was located on territories belonging to these particular nationalities, which contributed to cultural closeness and common historical traditions.

Local residents had a religious consciousness and were predominantly oriented towards traditional values; they liked the common cultural space that existed at that time. With its help, they resolved a large number of disputes and uncomfortable moments; the interaction of cultures can be traced in the descendants of the inhabitants of this state: Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians have respect and sympathy for each other.

What religion did the inhabitants profess?

If you are writing a history test and are asked to underline statements characterizing the Lithuanian-Russian state, one of the correct answers will be that the territory of the principality was for a long time divided into two religious parts. In the north-west of the country, until the end of the 16th century, the people professed traditional paganism; the rest adopted Orthodoxy in the 10th-11th centuries as part of Kievan Rus.

The rulers were not satisfied with either one, which is why Catholicism was actively spreading in the country. In the middle of the 16th century, Europe was swept by Protestant reforms, which reached the principality. In 1596, most of the country's Orthodox inhabitants submitted to the Union of Brest and recognized the Pope as the representative of their religion, and it was then that the Uniate was formed - a special Catholic Church. Islam and Judaism, which came there from the east in the 14th century, were also widespread in the principality.

Was it possible to get an education?

The state shows that writing began to actively spread here back in the 13th century, and already in the next century the first schools began to appear, where children from the noble classes were sent. Those who did not have enough money could take advantage of the conditions of itinerant teachers who taught elementary literacy for a modest remuneration (sometimes even for food).

In the 15th century, a large number of colleges and academies appeared, where Lithuanian boyars could receive knowledge only in the Western Russian language. Since the clergy also needed qualified personnel, corresponding schools were formed at the cathedrals. Most of the graduates of these institutions later worked in churches, but there were also those who received other secular professions. In the 16th century, some educational institutions began to teach in Latin, but the Western Russian language still prevailed in the learning process until the end of the 17th century.

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Russia is a very unusual state; at one time it was a kind of synthesis between European and Asian countries, which is why in the 16th century it acquired its own Calvinist schools. Later, Jesuit, Arian and Basilian educational institutions also appeared here, where in most cases future monks were educated. Graduates of institutions carried out missionary activities and often passed on their knowledge to poorer segments of the population.

Lithuania historically formed a buffer between the Russian Slavs and the Germans, especially when the latter destroyed the Baltic Slav tribes. The fact is extraordinary for the Germans, for even one German chronicler considered the death of the last Slavic obodrite an extremely important event and noted it along with the tedious enumeration of the deeds of bishops and dukes.

Thus. The Lithuanian-Russian state was formed as a result of classical pressure: from the north - the Order, from the west - the Poles, from the south - the Horde. (Koyalovich M.O., Lectures on the history of Western Russia, St. Petersburg, 1864 P.91-92).

The North-East was saved from the Germans by the Tatars. The Order was simply afraid to invade the Dzhuchiev ulus, realizing that nothing good would come of it. As an example, we can cite the famous case of 1269, when Prince. Yaroslav Yaroslavovich planned to attack the order together with the Novgorodians, taking revenge for previous grievances. Together with the prince, Baskak Amragan arrived in Novgorod with his son-in-law Aidar and a detachment of Tatars. The Germans of the Order, having learned that there were Tatars in the Russian detachment, “feared and trembled, sending their ambassador with great petition and with many gifts, and finished off with his forehead all his will, and all the Izdarish and the Great Bask and all the Tatar princes and Tatars; for boahusya name Tatar” (Quoted from: Nasonov A.N., Mongols and Russia, pp. 20-21).

Poland and Lithuania, because of the Tatars, could not gain a foothold in Galicia and Volyn until 1348. The Podolian Horde, which roamed here in the Ponizia, disturbed Poland and Lithuania with its raids through Galich, which was the reason for several papal bulls preaching a crusade against the Tatars, and the famous prince Daniil of Galicia could not think of anything better than to accept the royal title from the pope, in vain hoping that the West will help him in the fight against the Tatars. The successors of this prince pursued a more balanced policy. All of them were already captives of the Tatars, regularly paying tribute, but also taking advantage of the benefits of their position. Yes, book. Lev Danilovich several times led the Tatars against Lithuania and Poland when they pressed too hard on his possessions (Fipevich I.P., The struggle of Poland and Lithuania-Rus for the Galician-Vladimir inheritance, St. Petersburg, 189O, P.5O.)

Therefore, the prey of Lithuania before the death of Uzbek was mainly the western Russian border lands - the territory of the former Krivichi, the so-called. "Black Rus'". "White Russia", i.e. This part of Russia began to be called “Belarus” after Vytautas captured Smolensk, but even before Vytautas, starting with Gediminas, the great Lithuanian princes took the title: Rex Lethowinorum et multorum Ruthenorum, which is why a similar transfer of the name of the former Reutov-Suzdal land to the west was necessary. For more details, see the explanation of this issue in V.N. Tatishchev, “Russian History”, vol. 1., M.-L., 1962, pp. 355-357.

So, Lithuania enters the historical stage by the 12th century. from R.H. What was she like then? According to the general opinion of historians, even in the first decades of the 13th century. Lithuania was a bizarre mixture of Lithuanian clans and tribes, held together only by the weak ties of the priestly hierarchy. It must be said that Lithuania’s western neighbors took advantage of this most of all: by the beginning of the 13th century. the Germans completely slaughtered and Catholicized the large Lithuanian tribe of Prussians; Thus, of the previously 8 Lithuanian tribes, 2 had already disappeared by this time; the Golyad tribe disappeared earlier.* The Lithuanians, in their language and social institutions, represent a real Indo-European relic.

Their language is extremely close to Sanskrit. Thus, Schleicher assured that illiterate Lithuanian peasants easily understood simple sentences spoken to them in Sanskrit. At the same time, already from the middle of the 16th century. The Lithuanians themselves tried to develop their own view of their history and the origin of the Lithuanian ethnic group. Michalon Lytvyn was the first to put forward the thesis about the Latin-Roman origin of the Lithuanians, basing his conclusions on extremely close parallels between the Lithuanian and Latin languages, for example:

As for the third tribe of Yatvingians, we did not classify them as ethnic Lithuanians, because Quite large authorities, for example, A.A. Shakhmatov, did not consider them as such. He believed that the Yatvingians were descendants of the Avars, that part of this people that managed to break through to the north, fleeing the troops of Charlemagne. This movement of the Avars caused the movement of the tribes of the Western Slavs, Vyatichi and Radimichi into the Oka basin and the upper Volga. P.I. did not consider the Yatvingians a Lithuanian tribe either. Safarik, quoting the well-known Belarusian proverb, “looks like a Yotvingian”; he noticed that the racial type of the Yatvingians was clearly not Aryan. Lithuanians, as a people of Indo-European origin, are racially the complete opposite of the Yatvingians. LATIN Lithuanian fire ignis ugnis air aer oras day dies diena God Deus Dieva man vir vyras you tu tu living vivus gyvas etc. In a word, “After all, our ancestors, soldiers and Roman citizens came to these lands, once sent to the colonies to drive the Scythian peoples away from their borders. Or, in accordance with a more correct point of view, they were brought by the storms of the Ocean under Gaius Julius Caesar.” , - Michalon Ditvin. About the morals of the Tatars, Lithuanians and Muscovites, p.86. Over time, science came to a more correct point of view on this issue; the Lithuanian tribes were among the last to come to Europe and, occupying one of the inaccessible places in Eastern Europe, accordingly, lately began to look for justification for their own identity on the side.

Above, we have already noted the extremely primitive social connections of the Lithuanians before their active interaction with the Germans in the west and the Russians in the southeast. Until the XII century. There were no cities in Lithuania; the tribes lived in separate communities, each of which was headed by its own prince. Hence, by the way, such an incredible number of Lithuanian princes who were beaten in skirmishes with Russian princes, as the chronicles tell us about.

The only general Lithuanian force before the separation of the top tribal nobility were the priests. V.B. Antonovich even believes in this regard that if Lithuania had managed to close in on itself, then over time the Lithuanians would have developed a theocratic form of monarchy.

So, the high priest of all Lithuanians - Krive-Kriveito (pontifex maximus) was elected for life by a special priestly college of vaidelots (teachers, doctrinaires). Custom demanded that Krive-Kriveito sacrifice himself at the stake for the people if he lived to the point of decrepitude. Tradition has preserved a list of 20 high priests who did just that. The power of Krive-Kriveito was absolute and unquestionable among all Lithuanian tribes. Contemporary German chronicles compare his power to that of the Pope.

Near Krive-Kriveito we find Evart-Krive, the deputy pontifex maximus, and simply Krive, the heads of the colleges of priests. Of particular interest to us should also be the Krivula panel of judges who ruled on the basis of customary law and religious tenets. Krivule, on the instructions of Krive-Kriveyto, convened popular assemblies. The position of village elder lay on the shoulders of the vadelots, in whose absence this position was filled by the Virshaitos. In addition to the mentioned colleges, there were also colleges of shvalgons - (they performed marriages); Lingussons and Tilissons - (funeral rites). Fortune tellers, doctors, etc. were very famous. persons who were also members of priestly colleges. Women's priestly colleges were also strictly defined, for example, vaidelots, ragutins, burts, etc. It is unnecessary, I think, to say that the priestly hierarchy of the Lithuanians is very much reminiscent of the similar structures of the Brahmins of India and the ius sacrum (sacred system) of ancient Rome. *

The reason for the emergence of Lithuanian statehood was the contacts of the Lithuanians with the tribes of the Russian Slavs who stood in the 13th century. at a higher stage of cultural development than the first. In fairness, it must be admitted that from the very beginning it was the Russian princes who had the initiative: by invading Lithuanian lands and establishing fortified castles there, they, the princes, thereby seemed to incite the Lithuanians into their internal squabbles. We find especially clear confirmation of this in the Principality of Polotsk. It was here that the princes began to invite Lithuanian troops to help them, whose leaders were able to see firsthand the internal weakness of the Russian principalities.

Thus, in 1159, the Polotsk prince Volodar Glebovich refused to kiss the cross at peace with his opponents and went to Lithuania, into the forests, as the Ipatiev Chronicle reports. In 1162, three years later, this prince defeated the army of the Polotsk prince Rogvold Borisovich in alliance with Lithuania. In 1180, we meet many Lithuanians in the army of another Polotsk prince, Vsevolod Vasilkovich. Very early our princes begin to take wives from Lithuania. The beginning of the next century only intensifies these processes.

Another component of all-Russian policy in the Baltic states at this time was the fight against the Germans. Thus, according to the German

Details of the pantheon of Lithuanian gods and rituals can be found, for example, in: Famitsyn A.S., Deities of the ancient Slavs, St. Petersburg, 1995, p. 101-124.

chronicles, the Germans first of all had to join the fight in the Baltic states with the Russians; with their combat troops, and then with the Lithuanians. (See: Henry of Latvia, Chronicle of Livonia, M-L., 1938, pp. 71, 73, 85, 92-93 et seq.). In general, the appearance of Germans in the Baltic states is the result of the shortsightedness of the Polotsk princes. In 1202, one of them allowed the founding of a fortress (Riga), and in 1212 Prince. Vladimir of Polotsk had already had to refuse tribute from the Livs in favor of the Order (Ibid., p. 153). With the establishment of Tatar rule in Rus', the Germans were opposed by the Lithuanians, although not very successfully.

The first step in Lithuanian history in the proper sense of the word is taken by Grand Duke Mindovg 1, who already in 1215 acts as the head of several Lithuanian princely families: “Byakhu the names of the Lithuanian princes: behold, the oldest Zhivinbund, Davyat, Dovsprunk, his brother Mindog, brother Dovyalov Vilikail; and the Zhemoit princes: Erdivil, Vykynt; and Rushkovichev: Kintibut, Vonibut, Butovit, Vizheik and his son Vishliy, Kiteney, Plikosova; and behold the Bulevichs: Vishimut, Mindovg killed him and killed his wife and beat his brothers, Edivipa, Spudeyka..." (Quoted from: Presnyakov A.E., Lectures on Russian history, vol. 2, issue 1, M., 1939, p. 46). Over time, Mindovg becomes so strong that it switches to an active policy of seizing the western and southwestern lands of Russia. The only obstacle on his way: the Galician-Volyn prince Daniil in the south and the Tatars in the east. In 1263, Mindaugas was killed by his own princes, allegedly dissatisfied with Mindaugas’s disdain for everything Lithuanian. It seems that this is rather a traditional version, since Dovmont, an active participant in the conspiracy, flees with his entire family to Pskov, where he is baptized. The book itself Dovmont is very well known to us from the Pokovsky Judgment Charter. Obviously, the death of Mindaugas was actually caused by dynastic disputes among his entourage, and not by the Russophilia of this Grand Duke of Lithuania. The death of Mindovg caused a jam, in which Mindovg's son Voishelk emerges as the winner. Voyshelk was originally a fanatical pagan. The Ipatiev Chronicle characterizes the initial period of the activity of this prince in the following way: “Voishelk began to reign in Novgorodets in the abomination of fornication, and began to shed a lot of blood; to kill every day, three at a time, four at a time; whose days you cannot kill someone, then you will be sad; kill someone, then you are happy..." However, having become a neophyte, Voishelk is completely transformed; In the end, he goes to the monastery, the death of his father takes him out of the schema and, after punishing the murderers of his father, he finds nothing else but to transfer power in the Lithuanian principality to the Galician-Volyn princes. Voishelk was adopted by Vasilko Romanovich, the brother of Daniil Galitsky; Voishelk himself adopted Shvarn Danilovich, the latter’s son. So Lithuania is actually united until the time of Troyden Romuntovich (1270) under the rule of the Galician Danilovichs. Troyden actually spent his entire reign under the sign of defending his own claims to the throne of Mindaugas against the claims of the Danilovichs.

In this era, before the accession of the new Zhmud dynasty, the founder of which was Grand Duke Gediminas (1316-1341), the final Russification of Lithuania took place. The Lithuanian-Russian state itself, at the time of Gediminas’s accession, consists of 9/10 of the Orthodox Russian population. The written official language of Lithuania is the Russian idioma Ruthenuva, as Michalon Litvin complained, and the Cyrillic alphabet (Literas Moscovitas) was replaced by the Latin alphabet only at the end of the 16th century, when the first monuments written in Lithuanian actually appeared. The baptism of Lithuania took place, as is known, in 1387.

The fact that Lithuania chose the Latin alphabet over the Cyrillic alphabet and Catholicism over Orthodoxy, thereby dooming itself to internal conflict, can only be explained from the standpoint of the fear that the Lithuanians had of the absorption of themselves and their culture by Russian culture. In some ways, they resemble the Khazars, who adopted Judaism as an alternative to Islam and Christianity, thereby emphasizing their independence from their opponents in the West and South. Lithuania, well aware of the ephemeral nature of the legality of its domination over the Orthodox Russian lands, tried to prolong its agony, relying on the Catholic West. Although, if we take into account specific circumstances, Lithuania tried that year (1387) to find help against the Order, partly accepting the religion of its enemy and thereby, as it were, making the fight against it meaningless. However, the top of Lithuanian society failed to take the most natural step towards acquiring integrity and very soon became a mere appendage of Poland.

During the time of Gediminas, the first clash between Lithuania and Moscow occurred. Novgorod served as a bone of contention. In general, Novgorod and other Russian lands, which were under the rule of the Tatars, were extremely necessary for Lithuania in its fight against the Order. Especially Novgorod, the possibility of possessing which provided an extremely advantageous strategic position: the entire land border of the Order would be under direct attack from Lithuania-Rus. In addition, Novgorod is an important economic leverage. It now becomes clear why Gediminas hastened to support the fugitive Tver prince. But it was not there. In 1338, behind the figure of Ivan Kalita loomed the formidable figure of Uzbek with all the might of the Golden Horde. It is in Gedimin’s desire to find a favorable strategic position in the fight against the Order that one should, in our opinion, look for the reason for Lithuania’s subsequent involvement in Great Russian affairs, and not Gedimin’s conscious desire to unite all Russian lands under his rule, which is what the traditional point of view insists on, for example: In .B. Antonovich, A.E. Presnyakov.

The fact that perhaps such a line appears among the later princes, especially Vytautas, simply speaks of a change in the position of Moscow in relation to the Tatars. As soon as the Battle of Kulikovo took place (1380), which proved the possibility of confronting a large mass of Tatar troops, the Lithuanian princes began to realize this task for themselves. But the possibility of its desired implementation was soon put to an end in the battle on the Vorskla River in 1399. Whatever the outcome of the matter, to fight with Moscow for Lithuania meant to fight with the Horde, which is clearly indicated by the fact that we have repeatedly mentioned that Janibek sent Olgerd’s ambassadors to Simeon the Proud in 1350

In general, it should be noted that the Lithuanian-Russian state was extremely unlucky with princes after Gediminas. First comes Olgerd*,

* Here, for example, is how the Moscow chronicler characterizes Olgerd: “This same Opgerd is wise and speaks many languages and surpasses in rank and power more than anyone else; and abstinence is great, turning away from all vain things, not paying attention to the fun of playing and other such things, but diligence about your power always day and night; and you avert drunkenness: you don’t drink wine and beer, and honey, and any kind of drunken drink, because you hate drunkenness at all, and you have great abstinence in everything, and from this you have gained intelligence and a strong mind. acquisitive, and with such treachery he captured many lands and countries, and cities and reigns for himself, and holding back the fall of greatness, and his reign increased more than all, below his father, below his grandfather, it was so fast. him, where he wants to go with his army, or for which he gathers a lot of troops, because he himself

these warlike ranks and the whole army, not knowing where they are going: neither their own, nor strangers, nor alien guests; in the sacrament he does everything wisely, so that the news does not go out into the land, but he wants to attack her with an army, and with such cunning he does everything wisely... and there will be fear from him on everyone, and he will surpass in reign and wealth." Quoted from: Antonovich V.B ., Uk.soch., pp. 83-84. By the way, as G.V. Vernadsky noted at one time, Olgerd’s character was very similar to Ivan III, his direct descendant in the third generation.

Jagiello, and, finally, Vytautas, who turned out to be a very serious rival of Moscow. So it gives the Moscow Rurikovichs a lot of honor that they were able to outlast such serious opponents. It seems to us that, except for Dmitry Donskoy, none of the Moscow Rurikovichs dared to enter into open combat with them, hiding behind the Tatars in emergency situations and firmly insisting on what had already been achieved. Under Vasily II and especially under his son Ivan III, the situation changes dramatically and Lithuania is forced, in order to survive the dispute with Moscow, to turn to the help of Poland, help, of course, not selfish.

Due to its internal state, Lithuania was never able to develop its own modus vivendi of state communication, finding in copying the Polish system a catalyst for the destruction of its own statehood. Moreover, starting with Vytautas, with the final assignment of Kyiv to Lithuania, the thesis about the true location of the Russian metropolitanate emerged from oblivion. The church dispute over the location of the metropolitan see only stimulated the departure of the Western Orthodox and their falling away into a union with the Roman bishop. The Union of Florence added fuel to the fire. Ultimately, the question of faith only provoked the disintegration of the Lithuanian-Russian state; forced Catholicization, expressed in the prohibition to build new and repair old Orthodox churches (1481) and in the religious persecutions unleashed after the Union of Brest in 1595, naturally played towards the opposite goal, not towards unity, but towards a split in society. In this case, the Lithuanians, lacking the much-needed tact that the Tatars and Russians ultimately possessed, were unable to rise to a true understanding of their role among their Orthodox subjects.

Since 1500, there has been an intensified migration of service people from Lithuania to Moscow. A significant incentive for their resettlement was the fact that at home in Lithuania the Orthodox could not occupy a high social position, despite their birth and wealth; Moscow, on the contrary, provided a wide field of activity.

Power in the Lithuanian-Russian state was determined in a stable form when the Lithuanian state itself ceased to exist independently and was absorbed by Poland in the so-called. "Rzeczpospolita" is a "parliamentary union" in type. The entire period of independent (until 1385) existence of Lithuania can be defined as a time of unpunished (except for cases of opposition from the Tatars) seizure of Russian lands, when Lithuania, taking advantage of the weakness of its neighbors, pursued an active policy of conquest. For the most part, this is an appanage period when the Russian princes were guaranteed their own inheritance, subject to joining Lithuania. At the same time, this is also a period when the great Lithuanian princes cannot decide on their successors and divide the already united state again into appanages exactly as Yaroslav the Wise did; and only the natural decline of the Gediminovichs, as a result of the battle on the Vorskla River and other upheavals, allows Vitovt to stand out against the general gray background of serving boyars and princes.

Beginning with Vytautas (1392 -1430) and until the Union of Lublin in 1569, Lithuania gradually slides into the abyss of small-town feudalism, when, having experienced an unprecedented rise under Vytautas, Lithuania begins to experience unprecedented pressure from the East. At this time, a small-scale system was being formed here, which was completely devoid of a hierarchical center, as A.E. Presnyakov figuratively put it: “no patrimonial state was created from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.” (Lectures on Russian history, vol. 2, issue 1, p. 104). The Lithuanian-Russian state is an amorphous conglomerate of lands, aptly called “annexes” in our literature; and from these appendages, deprived of the saving anchor of autocracy in the stormy sea of aristocratic democracy, a common appendage is formed to the no less anarchic Kingdom of Poland. We must not forget that at that time the absence of a dynasty was tantamount to the absence of statehood.

In addition, the fundamental issue of Lithuanian statehood itself has not yet been resolved in science. It is very favorably set off by the example of the emergence and operation of national assemblies (valny soyms) in the Lithuanian-Russian state. There are two main points of view here.

One point of view is expressed by M.K. Lyubavsky: “The close and lasting union of Lithuania with Poland became possible only when in these relations, and not in external interests alone, Lithuania came close to Poland, when Litvin began to find something in Poland the same as at home and at home the same as in Poland.” (Lithuanian-Russian Sejm, M., 1901, p. 6).

Another point of view, rather functional in nature, was presented by N.A. Maksimeyko: “Issues of legislation and court, even after the formation of the general Lithuanian Sejm, were often resolved at the Sejms of individual regions... Another thing is measures related in one way or another to the defense of the state, they came from the general Sejms. It follows that the needs of military struggle and defense of the state constituted the constructive basis of the Lithuanian-Russian Sejm, while the functions of legislation and the court only came under its competence: this means that cases of the first category were necessarily considered at the Sejm, while cases of the second category only for reasons of convenience." (Sejms

Lithuanian-Russian state until the Union of Lublin 1569, Kharkov, 1902, p. 51). Accordingly, the reason for the emergence of Sejms in Lithuania should be sought in itself.

These two points of view actually indicate a struggle between two principles within the Lithuanian self-awareness. Where, exactly, did Lithuania get the idea of its statehood? And then, to which world should Lithuania be classified? The answer is obvious, and even Lithuanian nationalists are forced to admit to it that Lithuania has not played and cannot play any independent significance - its destiny is that of an outpost of the West in the East. Therefore, the answer is obvious, developed in great detail by Polish historiography, in this case M.K. Lyubavsky only voiced it: Lithuania received its statehood from Poland.

There are generally several main arguments possible here.

Firstly, the Union of Krevo of 1385, despite the apparent independence of Lithuania, crippled it quite significantly. Grand Duke Vytautas himself, under whom Lithuania reached its heights and was about to absorb Moscow, was in fact not an independent sovereign in his land; he was not a jure suo sovereign, but only a ruler for life, according to the terms of the Ostrov agreement of 1392.

Secondly, literally from the very beginning of their history, Lithuanian diets met not to resolve the issue of war and peace with Moscow, or with the Order, but to revise or approve a new union with Poland. This was the case in 1385, in 1401, in 1413 - the Grodel Diet, for example, was generally convened solely to revise the union treaty.

Thirdly, from the analysis of the modus a operandi of the Poles in relations with Lithuania, it is clear that they sought to raise the Lithuanians to their own level, which mainly resulted in the propaganda of the gentry ideology and its active calling for political existence.

Fourthly, the political physiognomy of Lithuania was finally determined when it firmly linked its destiny with the West and Poland. In general, since 1385, the Poles sought to consider Lithuania as part of their state, and not as another, independent state.

The final conclusion from all of the above, I think, will be that the foundations of Lithuanian statehood, which from the very beginning had the elementary nature of aggressive existence, subsequently turned into the artificial foundations of the military task of the Lithuanian-Russian state, which ultimately led to its collapse. Indigenous Lithuania, divided between Poland and the Order, played the role of a load that dragged southern and western Rus' to the bottom.

TERRITORIAL DEVICE According to the terminology of that time

LITHUANIAN-RUSSIAN STATE, everything is Lithuanian-Russian

the state before the Polish absorption was divided into two general parts: omnes terrae Lithuaniae - the Lithuanian lands proper, native Lithuania, Zhmud; and terrae Russiae, Lithuanias subjectas - Russian principalities, subordinate to the power of the Lithuanian state proper. The internal structure of these lands was determined and regulated by statutory zemstvo charters, exactly the same in purpose as the statutory charters of the Moscow principality.

It should be noted here that the Lithuanian charters that have reached us: Vitebsk land 1503 and 1509, Kiev land 1507 and 1529, Volyn land 1501 and 1509, Smolensk land 1505, etc., are much more detailed rather than the statutory charters of the Moscow princes. True, all Great Russian charters are older than Lithuanian ones and were issued under completely different circumstances than their Western counterparts. The internal structure of the appanages of Moscow and Lithuania is completely different in its guidelines: the general princely power in Moscow is only strengthening, the appanage princes are transferred to the center, but in Lithuania the princes are not transferred, they are left to their own devices and nothing is required of them except military service; in Moscow, the class principle, the principle of dividing the population by rigid partitions, temporarily triumphed only at the end of the 18th century; in Lithuania already by the beginning of the 15th century. We see a strong class organization and, as a consequence, the absence of the necessary state unity, etc.

Cities in the Lithuanian-Russian state receive governance according to Magdeburg law, as it was said in one act: “that place is ours from the law of Lithuanian and Russian and which, if it was first held in the law of the German Magdeburg, was changed to an eternal clock.” This seemingly progressive decision, in fact, soon led to the dominance of Germans and Jews in city life, on the one hand, and on the other, to the loss of communication between cities and their district-land, as was the case in the ancient Russian state. The Grand Ducal government also lost contact with the city communities, for the latter were now only obliged to regularly pay taxes, but the rights of participation of the burghers (from the Polish “mjasto”, i.e. “city”, hence “burghers” - “townspeople” translated into Russian) in the Great Valny Soymys were completely taken away from them. As a result, the land existed on its own, its cities - on their own. Only the gentry had this right: “Residents of one city thereby constituted the category of burghers. But residents of all cities in the state did not legally constitute the class of urban residents” (Yasinsky M., Statutory Zemstvo Charters of the Lithuanian-Russian State, Kiev, 1889, p. 21- 22). Drawing an analogy with

Moscow, you can notice that there were no townspeople in Lithuania, although there were burghers.

It is typical, but the ratio of statutory charters in Moscow and Lithuania looks exactly the same: petitions from the population about the loss of the old charter due to its dilapidation, references to the practices of neighbors, to the old days: “we don’t destroy the antiquities, and we don’t introduce new things, we want everything according to that sweep, as it would be for the Grand Duke Vytautas and for Zhikgimont,” we read, for example, in the Kiev charter of 1507.

The content and structure of the Lithuanian-Russian statutory charters are similar to the Moscow samples. Here we meet the promise of the central government not to give the newly annexed regions into private ownership: “And Viteblyany is not given to us as a gift to anyone,” we read in the Vitebsk 1502. letter, “but don’t give the city a voivode...” - in Polotsk in 1511. In detail, much more in detail than in Moscow examples, a kind of Habeas corpus act of the Lithuanian-Russian population is pronounced: “We should also give them a voivode in the old way, according to their will, and which they will not like the governor, but they will wash him in front of us, otherwise the governor will give them another, according to their will, "- Vitebsk 1503: "Those elders whom they would like to mark, we give them, but with ours will" - Zhmudskaya 1492; benefits for service: “and don’t put Vitblyan in an outpost anywhere,” - Vitebsk 1503; judicial guarantees: “And which Polotsk resident has something to complain to us about violence against a Polotsk resident who came to Lithuania alone, without a plaintiff: do not send us a child from Lithuania, write us your letter to our governor, even about mortal guilt,” Polotskaya 1511; “And don’t judge the courts of our great princes’ ancestors,” or “but don’t judge your own courts,” - Vitebsk 1503; “And without the right, we cannot execute people, nor destroy them, nor take away property; if someone blames someone, having besieged someone else, the right one will indicate that the guilty person will be executed through his fault. otherwise, do not execute him for any crime, neither for slavery, nor for shiya (death penalty - M.I.): to put before the open court of Christians - the Christian one who is in charge, and the one on whom it is important, and having examined the boundaries between them, the right to establish ", - in the Kiev charter of 1507; The right of petitions was not ignored either: “and we should accept the petition from the Vitblians,” - Vitebsk 1503. Finally, church affairs stand apart. Here at this point, perhaps, the most important reason for the instability of Lithuanian statehood was observed, despite the fact that in the Smolensk charter of 1505 the charter solemnly proclaimed: “First of all, we should not destroy the Greek law of Christianity, we should not impose taxes on their faith.”

Similarly, statutory charters regulated class rights and privileges (privileges), local government, financial management; traditional for this kind of acts are issues of civil law and procedure, as well as norms of criminal law and procedure.

However, immediately after the death of Vytautas (1430), the struggle between Svidrigailo and Sigismund acquired a national coloring. All Russian lands stand for the first, native Lithuania stands for the second. Moreover, some military positions: voivode, headman, castellan, marshal, etc. in the lands from now on became available only to persons fidelis catholicae cultores, i.e. for Catholics. The Lithuanian Grand Dukes, it would seem, do not violate anything; they guarantee the Orthodox what they already have by right of prescription (usucapio), but they do not at all guarantee them a new state, which is guaranteed only for Catholics.

CENTRAL In addition to the statutory charters in the Lithuanian-Russian

MANAGEMENT of the state for its internal organization

A special role was played by such national acts as privileges, especially privileges. book Alexander, issued in 1447. This act finally established representative forms of government and established limitations on central power.

According to this act, the Grand Duke undertakes to negotiate with foreign states only with the consent of the Sejm; he is prohibited by his authority from issuing acts that contradict the acts of the Sejm; he cannot legislate at all without the Diet; awards, especially large ones, are also made with the consent of the Sejm; and perhaps most importantly, taxes are now collected only with the consent of the Sejm.

The competence of the Sejm itself will look like this:

Election of the Grand Duke;

Regulation of the gentry's military service; -establishment of financial duties and taxes;

Conclusion of government loans;

Legislation.

Finally, at the Vilna Sejm of 1566, Grand Duke. Sigismund II Augustus made the following promise, which was subsequently included in the Lithuanian Statute of 1566: part. Ill, art. 7: “We and our descendants, the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, pray for the sake of the joys of our lordship of the same lordship, and for the sake of knighthood, lay down the Diets in the same lordship of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania forever, if so required.” . Undoubtedly, aristocratic democracy only strengthened with the final absorption of Lithuania by Poland.

The central government itself, represented by the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, also went through several periods, as did the formation of the Lithuanian-Russian state and its representative government.

Initially, the power of the Grand Duke resembles the type of power of the Grand Duke of Kyiv. In Lithuania we find exactly the same distribution of inheritance among the sons of the prince as in the ancient Russian state. There is no single sovereign dynasty. As we have already emphasized above, the last historical dynasty, the Gediminovichs, dissolved over time among the appanage principalities, the striped stripes of which were then represented by Western Rus'. The inheritance of the grand-ducal table among the Lithuanians followed the minority rule - the youngest son inherited the father's table; so Gediminas transferred his table (in Vilna) in 1343 to his youngest son Evnutius; Another thing is that two years later Evnutius was expelled from the grand-ducal table by his brother Olgerd. Olgerd himself left his table to his youngest son Jogaila, whose brother Vytautas was appointed ruler of all Lithuania, while his brother Jogaila became king of Poland and Lithuania.

It is known that Vytautas was going to break Lithuania from Poland; for this purpose he even intended to be crowned. The crown itself, which was sent to him by the Emperor of the German Empire, was intercepted by the Poles, and, as is known, to a large extent this insult was the cause of the nervous shock that provoked Vytautas’ fatal illness. The Lithuanians choose their own prince every time after the death of Vytautas and until the moment of final entry into Poland, i.e. before the Union of Lublin; it was exactly the same with the king in Poland. According to the figurative expression of the historian, the Lithuanians seemed to be raising a prince for themselves, just as the Novgorodians did.

Since 1569, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth has been a union-state with one monarch on two thrones. The electoral system was finally established in this state.

The monarch began to look more like a president for life. This system lasted until the last Polish king, Stanisław-August Poniatowski.

The competence of the Grand Duke was generally traditional for a major feudal lord of that time. However, at the same time, it experienced the strongest influence of the multi-ethnic territory on which this state was formed. The closest analogy here is possible with the Spanish state, the process of formation of which intensified approximately in

The period we are considering.

The power of the Lithuanian Grand Duke is based in the period we are considering on a contractual basis; this is not least due to the fact that the Grand Dukes of Lithuania were unable to establish a strict system of succession to the grand princely throne, such as we find in Moscow; Moreover, the Lithuanians proceed quite early to the election of their Grand Duke, which does not at all contribute to the firmness and unity of the central government. All this results in the fact that the Grand Dukes are forced to conclude a number of agreements (pacta convenanta) with their subjects, of which we can distinguish the two largest types. These are privileges and letters of merit. The first type of documents is issued to entire estates of the state, the second - to individual lands - annexes.

The ratio of such agreements is clearly visible, for example, in the “charter of Casimir” dated 1457: “For such kindness and kindness, gifts and other kindnesses, mercifully give them; for then later, both for us and for our services, the lax will be found, if they see for themselves Such caresses are comforting." (Vladimirsky-Budanov M.F., Reader on the history of Russian law, issue 2, p. 20).

We repeat, ratio, i.e. The main reason for this kind of humiliation of the central power in front of the periphery is not only the inability of the power itself to assert itself in the form of a rigid domini- and imperium, but also the absence of a clearly developed idea of the state among the Poles and Lithuanians. The state is not an apartment with all the amenities; the state is, in the figurative expression of G.V.F. Hegel, the embodiment in reality of the idea - “this real God.” The state is a strict hierarchy; a hierarchy sanctioned by a firmly defined idea.

However, it is worth asking the Pharisaic question: what for what? Is the state for the people or vice versa? This is exactly how the mythologized consciousness tries to fight what it cannot understand; The way out, therefore, is to vulgarize, to reduce the lofty human aspiration to the realm of the base, animal, totalitarian. But a person’s thought, its structure, is the state; the state of this particular person!

So let's repeat. We have before us the purest pacta convenanta, not a realized dominium. This is not power, but a contract, an agreement on mutual recognition and assumption of obligations. In essence, it is not a state at all. In any more or less nationalized community, the cause of such state formation is power itself, and not the myth of the common good, etc.

The legislative function of the Grand Duke of Lithuania could only be carried out in unity with the Great Valny Soim (Sejm) on the one hand, and on the other, with the direct participation of the population who filed petitions. The latter is especially clearly visible from the contents of the charters: “The princes and boyars and servants of Vitebsk beat us with a chol, and the townspeople of the city of Vitebsk, and the whole land of Vitebsk,” we read in the Vitebsk charter of 1503; “Vladyka Joseph of Smolensk, and the okolniki of Smolensk, and all the princes, and the Panovs and boyars, and the burghers and mountain people, and all the ambassadors of the place and land of Smolensk beat us with a chol,” - Smolensk charter of 1505, etc.

We certainly read about the first case of legislation by the Sejm, for example, in the preamble of Casimir’s Code of Law from 1468: “We, together with the princes and lords, were our joy of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and having guessed with all the embassy, we ordered it like this...”.

Perhaps what makes the Grand Duke stand out is his right to court. In civil law terms, the position of the Grand Duke “his property” seems to be no higher than the position of other service classes; see Regulations, see art. 9, 11, 22 Code of Laws of 1462. At the same time, there are known protected properties that have the same status as the treasury.

The apparatus of state power in Lithuania is represented by a detailed ladder of service ranks. Orders - positions - experienced the strongest influence of Poland and Germany, through Magdeburg law.

So, the general scale of orders in Lithuania was as follows.

Hetman (from German: Hauptman) has been known in Lithuania since 1512. He was the commander-in-chief of the army and the highest military court. He had the right to life and death of the defendant. The post of hetman, as a rule, was connected with other higher areas, for example, the chancellor.

Chancellor. He was formed, according to academician K.N. Bestuzhev-Ryumin (Russian History, vol. 2, issue 1, St. Petersburg, 1885, p. 59), from the position of clerk under the Grand Duke. Mention of it dates back to 1450. The Chancellor was the official notary of the state.

Treasure of the earth and the courtyard. The essence of the financial management bodies of the state. Skarbnitsa - treasury. The first was responsible for accounting and distribution of incoming taxes, the second managed state property.

Voivode. Corresponded to our governors, and later to the governors themselves. These are typical palatines - representatives of the center (in this case, the “Palace”) in the controlled territory. Subordinate to the governor were constables. They helped the governors administer justice; we find some analogue in our bailiffs, etc. referee staff. Among the general mass of constables, there were also the so-called “court constables” - persons of the Palace Administration, such as the krachiy, the cook, the podkamornik, the dvorchiy, etc., who made up the apparatus of the courtyard treasurer. The governors themselves are very often referred to as “powers” in their acts.

In addition to the constables, the local apparatus of the Palatine Administration included the so-called. "castellans". The first mention of them occurs in 1387. At the same time, before 1516 there were only two castellans in Lithuania; after this date, castellans began to be appointed to each land of the voivodeship.

Headman. Unlike Rus', the headman in Lithuania is the head not of the community, but of the entire land. In them we find a vestige of the power of the former appanage princes. A distinctive feature of this position was that it (the position) was inherited.

Lithuania is also known for its class division. Very early in the Lithuanian-Russian state, class government bodies were established, of which the “marshals” and “voits” attract our attention.

"Marshals" are representatives of the gentry who represent their interests before the central and local authorities.

"Voity" (from German Vogt) appeared in urban communities of Lithuania along with Magdeburg Law. In essence, Voight is the head of the city community.

In addition to the above-mentioned general positions in Lithuania, there was also a wide variety of small ranks: cornet - standard bearer, tiun, mayor, etc.

The entire history of this state was saturated with artificiality. It should have fallen on its own after the disappearance of its main task - containing the aggression of the Order. Therefore, when Ivan the Terrible inflicted a crushing defeat on the Order, it was only a happy accident - union with Poland and

the subsequent Troubles in the Moscow State and the existence of this ugly product of Russian separatism for another two centuries.

arstve - extended