Characteristics of Volga Svyatoslavovich. Origin and description of the image. Characteristics of Mikula Selyaninovich from the epic "Volga and Mikula Selyaninovich" Characteristics of the main characters of the epic Volga and Mikula

And Mikula Selyaninovich - one of the three senior heroes of Russian epics. Some believe that the name Volga comes from the name of the historical prince Oleg. It is possible that Oleg’s brilliant victories seemed miraculous and supernatural to the people, and from the image of this prince, who was known during his lifetime as a “prophetic”, that is, a sorcerer, a fabulously heroic image grew.

Volga is of wonderful origin - the son of the princess and the Serpent Gorynych. Volga is a prince himself, with a squad, and at the same time a werewolf wizard. His “cunning-wisdom” lies in the ability to “turn around” into different animals (a fierce beast, a gray wolf, a clear falcon, a bay aurochs, a pike).

He is an unusually strong hero. When Volga was born,

The mother of cheese, the earth, began to tremble,

The blue sea shook.

From early childhood, Volga learned various “tricks and wisdom.” He learned to understand the language of animals and birds, he learned to turn himself into animals, birds and fish;

Walk like a pike fish in the deep seas,

Flying like a falcon bird under the clouds,

Like a gray wolf, prowling the open fields.

Thanks to this ability to turn around and, when necessary, turn around her squad, Volga wins wonderful victories. One epic tells how Volga Svyatoslavich decided to “fight the Turkish kingdom.” Turning into a “small bird”, he flew across the “ocean-sea”, flew to the court of the Turkish Sultan and, sitting on the window, overheard a conversation between the Sultan and his wife about how the Sultan was going to “fight the Russian land.” But the Sultan’s wife felt that the “little bird” sitting on the windowsill was none other than Prince Volga Svyatoslavich himself, and told her husband about it.

Then the Volga bird flew up and immediately turned into an ermine, which made its way into the chambers where all the weapons of the Turkish army were kept. And then Volga the ermine began to bite all the strings of the Turkish bows. He did not gnaw them, but only bit them unnoticed, so that when the Turks pulled their bowstrings with an arrow, preparing to shoot, all their “silk bowstrings would burst at once.”

Volga and the Sultan's wife. Cartoon

Having then flown safely over the Ocean-Sea bird, Volga gathered his “good squad”, turned it all into pike and thus swam across with the Ocean-Sea squad. The squad - already in human form - approached the Turkish city, but it turned out that the city was surrounded by a strong, indestructible wall, and the “patterned” gates were tightly locked.

Then Volga again resorted to magic. He turned his entire squad into “murashchiki” (ants), who crawled through the patterns and cracks of the strong city gates and, already outside the wall, turned again into a strong squad and rushed at the enemies. The Turks grabbed their bows and arrows, pulled the “silk strings” - all the strings burst at once - and Volga conquered the entire Turkish kingdom.

In one epic Volga, also,

Famous fairy-tale characters, whose images seem familiar from childhood, have a centuries-old history. The warriors and heroes from the traditions and legends told by grandparents are not just representatives of traditional folklore, but characters who personify the spirit and traditions of the great Russian people. The heroes of epics are endowed with remarkable talents for protecting their native land. In the line of mighty warriors there is a place for Mikula Selyaninovich.

History of creation

Mikula Selyaninovich is a hero sung in an epic called “Volga and Mikula Selyaninovich.” The epic was composed over several centuries, as the legend underwent changes and was passed on from mouth to mouth in various interpretations. The characteristics of the heroes are accurately conveyed in the version composed in the north of the country after the collapse of Kievan Rus. It is unknown how the description of Mikula was composed, but Volga (Oleg) Svyatoslavovich is a real historical person. The prince was the king's cousin and grandson.

The epic lacks unity of place, time and action. It involves a description of fictional events involving fairy-tale characters, but the etymology of the word indicates that some episodes actually happened.

The narrative describes a meeting of two heroes: a prince and a peasant plowman. The first goes to war, and the second, the plow hero, cultivates the land. The simple peasant is presented in a noble appearance. This is a well-groomed man in clean clothes and a painted caftan. Mikula is wearing green high-heeled boots and a feather hat. Such attire did not correspond to the usual clothing of a plowman, accustomed to working with the land and exhausting work. But a stately hero must, according to the traditions of the epic, have a beautiful outfit, and this rule is observed.

The specificity of the epic “Volga and Mikula Selyaninovich” lies in its artistic techniques. It includes elements of archaic language and numerous repetitions. Through colorful epithets, details of clothing, character traits of the heroes, and the life surrounding them are described. In the epic, the images of a peasant and a warrior are contrasted with each other.

At the same time, the work of a simple farmer is placed higher, because a plowman could be called upon to defend his homeland at any moment, and not everyone is given the opportunity to work on the land. There is also a version that the legend contrasts the images of two deities, the patrons of agriculture and hunting.

The motive for praising the work of plowmen is vividly described in the episode when Prince Volga orders his squad to take up the bipod. The warriors cannot overcome it, but Mikula Selyaninovich copes with the task in one go.

A hero who can bypass a squad is a true defender of the Russian land and its cultivator. The writers of epics speak kindly and affectionately about the hero. It is noteworthy that throughout the narrative the hero is called nothing less than oratay. And only in the finale Mikula’s name is revealed. The hero talks about his achievements without bragging.

Biography and plot

In the epic about Mikul Selyaninovich, the main characters were two characters: himself and Prince Volga. The first meeting takes place when, according to the behest of Vladimir Monomakh, three cities pass into the possession of Oleg. The prince goes to inspect the property. On the way of the squad, they meet a stately hero, who can be seen from afar, but they manage to get to the curious character only after three days and three nights. Hyperbole of this kind shows people's admiration for the hero.

Mikula is a plowman. He cultivates the land with ease, uprooting stumps and stones with a wooden plow decorated with precious stones. Mikula's mare is hung with silk tugs, and the hero's outfit itself does not look like a simple peasant dress. It becomes clear that the reader is dealing with a hero for whom hard plowing is entertainment.

Mikula Selyaninovich is presented in the image of a hero revered most of all in Rus'. Holidays were dedicated to work related to the land, and traditions and legends were associated with it. Mikula is a folk hero; his prototype was considered the patron saint of the peasantry.

This image was the personification of the Russian farmer. Therefore, the creators of the epic do not mention the name of the hero’s father: Selyaninovich is combined with the word “village,” which means that the parent was a simple Russian people.

Mikula has an easy-going character and a kind soul, a generous and hospitable person. Without it, the princely warriors are not even able to pull out a light bipod, which means that the royal power is based on the strength of the plowman. Rus' is based on a simple village peasant who feeds the people and protects his homeland from misfortunes.

Heroic strength does not make Mikula a braggart. The hero is modest and calm, does not get into trouble and simply communicates with the prince. A conflict-free character belongs everywhere. He pleases those around him, knows how to work and relax well.

Orthodox Rus' is famous for humility and forgiveness, but is always able to defend its honor and protect its neighbor. In the episode of the attack by robbers demanding pennies, it is clear that the righteous Mikula is ready to endure and show loyalty to the last. Having lost his temper, he will be able to reason with his opponents by force.

Popular Russian heroes are considered to be those who fought with Khan Tugarin, who opposed and whose opponent turned out to be. But folk legends also described other heroes who defended their homeland from the invasion of dark forces.

Mikula Selyaninovich, a simple plowman, struggled with the “saddlebag”, which contained “all the earthly burden.” Volkh Vseslavyevich is a sorcerer who helped defeat the Indian king. was considered a reveler hero, and gained fame after the Battle of Kulikovo.

The biography of heroes is rarely described in detail. It is often unclear who the hero was before the heroic power awakened in him. Sometimes it is not even known where he was born. But the main exploits for which the characters became famous were passed down in detail from mouth to mouth, considered a national treasure, and supported the spirit of the Russian people, who needed defenders.

Heroic strength is one of the favorite subjects of fine art. The paintings, painted in the same manner, told about the exploits and travels of Russian heroes. Among the admirers of Russian folklore were painters and Ryabushkin.

The legendary personality of the Russian plowman-hero Mikula Selyaninovich is known from the epics of the Novgorod cycle. The image of the main character is filled with spiritual strength, courage, and love for his native land.

Historical image of the hero

Mikula Selyaninovich was a plowman endowed with remarkable strength and, according to epics, he was the only one who could lift the “earthly draft.” It embodies the collective image of the Russian peasantry, where the main role is played by hard work, respect for the homeland, perseverance and steadfastness in the face of enemies. The main life value for the folk hero is his tool of labor - the plow, and his favorite pastime - plowing. Before the power of the plowman, the witchcraft powers and the power of the princes, the strength of the entire squad, pale. The labor prowess of Mikula Selyaninovich glorifies ordinary Russian people, who are alien to laziness and weakness, who work on a grand scale from dawn to dusk.

The main life value for the folk hero is his tool of labor - the plow, and his favorite pastime - plowing. Before the power of the plowman, the witchcraft powers and the power of the princes, the strength of the entire squad, pale.

Characteristics of basic qualities

The main qualities of the peasant Mikula Selyaninovich are incredible physical strength, dexterity, love of work, spiritual purity, care for the Russian land, and tirelessness. Unlike the well-known images of heroic defenders, Mikula directs his immense power into a peaceful channel, into fertile soil.

He does his work with pride and hums happily while ploughing. It is a great honor for the glorious hero to work his mother land every day, so he comes to the field in elegant attire and is always neat. Mikula is thrifty. Having once forgotten a plow in a furrow, he returns for it, worrying like a proprietor that a passer-by will not take it away.

The hero of the epics has an expressive appearance: thick curls, black eyebrows, clear hawk eyes. A plowman is characterized by a reverent attitude towards his mare; he raised her from a foal and takes care of her, grooming her every day. The peasant is distinguished by his hospitality: at the end of the arable season, he will happily gather guests at home and give the peasants some beer of his own making. In the description of the worker’s abilities, one can note the exaggeration of qualities; these exaggerations once again emphasize the people’s love for Mikula.

Russian epic character

Novgorod epics glorifying the image of the Russian plowman have been known to many since childhood. These are “Volga and Mikula Selyaninovich” and “Svyatogor and Mikula Selyaninovich”.

According to the plot of the first epic, Prince Volga and his retinue go to Russian cities, transferred into his possession by Prince Vladimir. Having met the plowman Mikula in the field, he admires his strength and power and offers to go with them to resist robbery. The peasant agrees. At the end of the epic, the strength of the prince and his squad, who could not pull the plow out of the furrow, is contrasted with the heroic power of the simple Mikula, who pulled the plow out effortlessly. There is an alternative version of the ending, where Mikula, having set off on a journey, becomes the governor of one of the cities, saving Volga’s life.

In another epic, the extraordinary strength of the Russian worker is compared with the abilities of the giant Svyatogor. The epic character of ancient Russian mythology, Svyatogor, is many times larger than Mikula in size and power, but is not able to catch up with the plowman in the field at work and cannot cope with his earthly burden.

The personality of the epic hero Mikula Selyaninovich occupies a worthy place among the works of Russian folklore and arouses pride among contemporaries for the unshakable spirit and hard work of the Russian peasantry.

Zh.I. ZHITELEVA,

IN AND. RESIDENTS,

Lyubertsy

Reading the epic “Volga and Mikula Selyaninovich”

7th grade

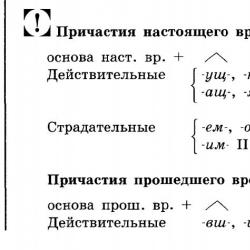

The originality of the Russian epic from an educational and methodological point of view lies, first of all, in the presence of a large number of words and figures of speech that are completely unusual for the modern Russian literary language. Among them there are also those, without explanation of which certain parts of the work turn out to be completely incomprehensible to the student. Therefore, reading the epic should be accompanied (or preceded) primarily by linguistic and semantic commentary. The age of the students and limited time do not allow for a complete linguistic analysis of the work, but some linguistic facts of the “old times”, the most necessary for understanding the text and the most interesting for seventh graders, are explained by the teacher. These are outdated grammatical forms of words, and dialectisms, and words that have fallen out of use due to historical changes in people’s lives, and constructions of words unusual for the spoken language, which were created under the influence of the peculiar poetic tradition of telling epics. Along the way, students receive some information about the stylistic and literary elements of the epic, which characterize the features of the work from the ideological and artistic side, which is also a necessary condition for a full perception of the ancient legend.

We consider it most appropriate to present the material of the article in the form of a “shorthand” recording of a lesson, but, of course, not any specific one, but generalizing many real lessons. This will allow the literature teacher to see the described methodology in an undistorted form and objectively evaluate its strengths and weaknesses; those of our colleagues who wish to take advantage of this lesson development will find that it is possible to change and correct in our experience in order to improve the proposed methodology or adapt it to the characteristics of their class.

For the lesson we are making a special poster on a drawing sheet of paper (see its reproduction), which will be a good help in explaining the lexical material of the lesson. The text of the epic is quoted from the “Textbook-reader for the 7th grade of general education institutions”, author-compiler V.Ya. Korovina. 2nd ed. M.: Education, 1995.

The lessons were taught by Zh.I. Zhiteleva.

DURING THE CLASSES

We already know the following types of oral folk art: fairy tale, proverb, saying, riddle. Today we will add epics to this list of types of works. Bylinas are works of Russian folk poetry about heroes. Word epic comes from the word true story . In the epics, as you might guess, it is said that was. We will find out how correct your guess is in the next lessons. And today our task is to read one of the epics.

However, reading the epic in order to see how interesting it is is not easy, because the epics were created in ancient times and have carried through the centuries to the present day a lot of things that require explanation. The epic can be read if you read slowly and thoughtfully; it does not tolerate thoughtless reading. Since epics were created in the distant past, they are also called in the old days .

Showing the entry on a poster.

These are the words - Oratay is yelling - from the epic that we will read today. Who knows what it means oratay ? (Plowman.) What does Oratai do? (Showing the verb yells .) What means Oratay is yelling? (The plowman plows.) What do you think, noun oratay and verb yells - words of the same or different roots?.. “Oratai yells” - that’s what the ancient Slavs said.

Epics usually sing military exploits of heroes. We will read an epic about the hero plowman, oratai Mikul Selyaninovich. Selyaninovich– from a noun village. Patronymic, or rather, nickname Selyaninovich indicates that Mikula is a villager, peasant .

Bylinas were created and passed down from generation to generation by simple working people, who bore on their shoulders both the hardships of military exploits and the hard daily labor of peasants. Through epics, ordinary workers tried to brighten up, at least in their imagination, the exorbitant burden of labor and military exploits, to show the greatness of a working man and his superiority over others. The people loved the epic heroes. Now we will see with what pride in the heroic plowman the epic storytellers talked about Mikula’s work in the field.

Open the textbook to page eleven, find stanza six*. I will read, and you follow me in your books and listen carefully.

Like Oratai yells in the field - whistles,

And he marks the furrows,

And he turns out the stump roots,

And large stones are thrown into the furrow.

Oratay has a nightingale mare,

She has silken little buns,

Orata's bipod is maple,

The damask boots on the bipod,

The bipod's snout is silver,

And the horn of the bipod is red and gold.

I turn to the poster.

Mikula yells (plows) bipod . Here is a drawing of a plow. “The bipod is made of maple.” What kind of wood is the bipod made of? (Maple.)

« Omeshiki

on the bipod there are damask steel.” These metal tips of the plow are called omeshas. The plow that Mikula plows has holes in it damask, that is, made of the best metal, damask steel.

Here is “at the plow” suckers

, a shovel for turning away the earth, in order to “throw the earth into the furrow.” “The bipod’s pin is silver.” Rogaczyk

- plow handle. “And the horn of the bipod is red and gold.”

This live

, between them there was a horse. They put it on the horse's neck clamp, the crimps were tied to a clamp tugs

. “Her little buns are silk.”

“At her” - that is, at the horse. And Mikula has a horse nightingale. See in the text: “The screaming mare has a nightingale.” Solovaya a horse is a horse of this color: it is light brown itself, but the tail and mane are white.

The heroic plowman’s mare is also a heroic one. Mikula on her horse “turns out stumps and roots” and does not go around large stones, as is usually done, but throws them into the furrow along with the plowed soil, as if not noticing them.

If Mikulina is a mare step goes (from verb step), then other horses have to gallop to keep up with her; what if she breasts will go, no horse can keep up with her. Mikula bought her “as a foal from under her mother,” that is, as a suckling foal, and paid a very high price for her - five hundred rubles. If his horse were not a mare, but a horse, then it would have no value at all.

The people's love for the epic hero plowman is also visible in the description of Mikula's appearance. We read the next stanza, the seventh. T., read the first two lines; the rest follow the book.

And Oratai’s curls are swaying,

What if the pearls are not downloaded and scattered?

“Downloaded pearls”, or “downloaded pearls” - selected pearls, round, smooth, of the highest quality. Imagine: pearls were poured out of a bag, and pearl balls rolled across the table. “Oratai has curls... are the pearls scattered?” The next two lines will be read by T.

The screaming eyes and clear eyes of a falcon,

And his eyebrows are black sable.

What are Mikula's eyes compared to? (With the eyes of a falcon.) What about the eyebrows? (Sable - like black sable fur.) Now listen to the description of the boots that the heroic plowman is wearing:

Oratai's boots are green morocco:

Here are the awls of the heels, sharp noses,

A sparrow will fly under your heel,

At least roll an egg near your nose.

Mikula's boots are made from morocco. Saffiano – tanned goatskin, soft and elastic. “Oratay’s boots are green morocco.” Note: not “boots”, but “boots”. The next line will be read by T.

Here are the awls of the heels, the noses are sharp.

Pyat means “heels”; nouns heel And heel- related words. “Awl of the heel” - what are heels, that is, heels, compared to? (With an awl.)“Awl heels” - that is, heels are thin, like an awl. “Sharp noses” - what kind of noses do the boots have? (Spicy.)

A sparrow will fly under your heel.

If “a sparrow flies under your heel,” that means what kind of heels are Mikulina’s boots: low or high? (High.) The heels are so high that a sparrow could fly by. “With an awl of the heel, a sparrow will fly under the heel,” - the heels of Mikulina’s boots are very thin and high. T will read the next line to us.

At least roll an egg near your nose.

“The noses are sharp... you could roll an egg near the nose,” - the toes of the boots are sharp and so even that you could roll an egg. The last two lines will be read by T.

The orata has a downy hat,

And his caftan is black velvet.

As you can see, the plowman went to work in the field in smart clothes, as if on a holiday.

Prince Volga Svyatoslavovich drives past the place where Mikula is “yelling oratay.” The epic prince Volga Svyatoslavovich is also not simple: he is a hero, and besides, he also has witchcraft powers, magical wisdom. He can turn into birds, fish, animals, and, having become a bird, fish or animal, he continues to possess extraordinary, heroic strength. This is what one of the epics says about Volga:

When the young moon was born, the moon was bright,

Then Volga the hero was born.

Volga became ten years old,

Oh, he wondered, Volga, but in wisdom,

Oh in wisdom, Volga, but he is in cunning cunning:

He flies like a bird and under the cover,

To walk like a fish and into the depths of the camp,

Walk with animals and into dark forests.

Volga turned around and looked like a small bird, -

Volga flew away and he was under the cover,

Hey, he scattered the whole bird.

Volga turned into a fresh fish,

Oh, Volga went to the depths of the camp,

He chased away all the fish.

Volga turned into a fierce beast,

Ay, Volga went into the dark forest,

He drove away all the animals.

In the epic that we will read today, Prince Volga and the plowman Mikula meet, and we get the opportunity to compare, compare the prince and the plowman, to identify which of them has more merits - virtues that are not external, but true, those that make both a person a hero and They serve the people around them for the benefit.

Prince Volga received from his uncle, Prince Vladimir of Stolnokiev, three cities and went to these cities to get tribute for pay went. With him is a “good squad” of “thirty fellows without a single one” - that is, how many squads are with him?.. And what does it mean good?..

Find stanza four on page ten; I'm reading, you follow me through the book.

We drove to Razdolitsa, an open field,

We heard shouting in the open field,

Like Oratai yells in the field - whistles,

Oratai's bipod creaks,

The little guys are scratching the pebbles.

We drove all day from morning to evening,

We couldn’t get to Oratai.

They were driving and it was another day,

Another day is from morning to evening,

We couldn’t get to Oratai.

More two days Volga had to get to Mikula after Volga heard Mikula’s voice and the creak of his bipod - that’s what a mighty hero the plowman was!

Of course, the strength of man, his capabilities, his power are clearly exaggerated in this description. Why was such an exaggeration allowed in the epic?.. To emphasize how colossal efforts requires of a person his main activity - cultivating the land. To show what mighty people follow the bipod, plowing their native fields. To finally express pride for the cultivators who are powerful in their work.

Epic storytellers often used the artistic technique of exaggeration. The power of the defenders of the homeland was exaggerated, and the strength of the enemy with whom the Russian heroes had to fight was exaggerated. Such exaggeration in works of art is called hyperbole. Hyperboles are very often used in epics; one might say that epics are almost entirely built on hyperbole. Let us remember from the description of Mikulina’s boots: “...a sparrow will fly under your heel.”

So, Volga had to travel for more than two days to listen to the plowman’s voice. But finally the prince reached the farmer and saw him. T. will read to us how Volga greeted the peasant - look at the eighth stanza.

Volga says these words:

- God help you, oratay-oratayushko!

Yell, plow, and become peasants,

And you should mark the furrows,

And turn out the stumps and roots,

And throw big stones into the furrow!

Volga, greeting Mikula, wishes him God's help in his hard work. And what better thing can you wish for a peasant worker than help in his difficult work?! As you can see, the epic again reminds us of the hard work of a plowman.

T. will read Mikula’s response to Volga’s greeting.

Oratai says these words:

- Come on, Volga Svyatoslavovich!

I need God’s help for the peasants.

Where are you, Volga, going, where are you going?

Does everyone understand the phrase “I need God’s help for the peasants”?.. Volga says to Mikula: “God’s help for you!” Mikula replies: “I needed God's help to become a peasant." You see, the epic here also does not shy away from the topic of hard peasant labor.

“Where are you going, Volga, where are you going?” - asks Prince Mikula. Volga replies that he is going to the cities to receive tribute, for pay goes. Mikula tells Volga that in those cities there live robber men, they will cut off at the bridge slugs (long logs on which the bridge is laid) - they will cut down the slugs and drown the prince in the river.

I was recently there in the city, the third day,

We now use the word fur in the meaning of “animal hair” or “the tanned skin of a fur-bearing animal.” Who can tell what a noun means? fur in the expression “salt is three skins”?.. Compare the pairs of words: verse - rhyme, laughter - chuckle, fur -? (Bag.) Fur- a bag of animal skins.

Which of you knows the word pood? Pud– a Russian unit of weight equal to approximately sixteen kilograms.

Mikula says: “I bought three furs of salt, each fur cost a hundred pounds.” There cannot be a bag that would hold one hundred pounds of salt. Again, hyperbole is used in the epic. We read stanza eleven, follow me in your textbooks.

Here the oratay-oratayushko spoke:

- Oh, Volga Svyatoslavovich!

There live little peasants and all the robbers,

They will chop down the viburnum slugs,

May they drown you in the river and in Smorodino!

I was recently there in the city, the third day,

I bought three whole furs of salt,

Each fur was worth a hundred pounds...

The next line will be read by T.

And then the peasants started asking me for pennies.

For some epic storytellers, this sentence sounds like this: they asking for pennies road . As we see, the robber men are “asking” for money. But the robbers didn't ask! – ask money from passers-by; therefore, here we are talking about people who were involved in robbery on the roads. The next line will be read by T.

I started dividing them pennies.

Did Mikula give money to the robber men or not? (Gave.) The next line will be read by T.

And the money became scarce.

Is the meaning of what was said clear? Mikula’s money “has become few put." The next line will be read by T.

There are more men being hired.

Do I need to explain this phrase?.. Mikula’s money “has become few put”, and the peasants demanding money from him are all “ more is placed." Let's see how events developed further. T., read the following lines.

Then I started pushing them away.

He started pushing me away and threatening me with his fist.

I put them here, up to a thousand.

Mikula didn’t have enough money for everyone, so he had to deal with the robbers with his fists. “I put up to a thousand of them here,” says Mikula. The prince realized that his squad of “thirty young men without a single one” could not cope with such a horde of robbers, and Volga invited Mikula to go with him “as comrades.”

Now I will read the entire epic in its entirety. As you listen to it, pay attention to the following.

Nouns are usually used in the diminutive form. Druzhinushka, uncle, father, mother, oratayushko, countrywoman, groove, bipod(not “plow”), from Volga stallions(not “stallions”), even the robber men are named peasant robbers.

Adjectives are also sometimes found in the diminutive form. Mare nightingale(instead of "nightingale"), bipod maple(instead of “maple”).

We will meet constant epithets, many of them are already known to us from other works of oral folk art: horse Kind, field clean, Sun red, sky clear, forests dark, seas blue, friend good, bipod maple, bush Rakitov.

Adjectives are often used in short form. For example, in comparisons when describing Mikula’s appearance: downloaded pearls (instead of “rolled pearls”, which means “round, smooth, selected pearls”), eyes clear falcon (instead of "clear falcon"), eyebrows black sable (instead of “black sable”), boots green morocco (instead of “green morocco”), caftan black velvet (instead of “black velvet”) and so on.

Let's meet verbs in the indefinite form with ancient endings -ty . For example: “the men will become me praise"(instead of "praise"), "could not shout get there"(instead of "get there").

All these poetic features of the epic are also characteristic of other works of oral folk art, primarily fairy tales and songs. Now listen to the epic.

It takes approximately eleven minutes to read the epic.

Homework: learn to read epics expressively. Those who wish can learn by heart one of the stanzas of the epic (sixth, seventh or fourteenth); everyone who learns a stanza and recites it expressively will receive a good grade.

* In the first, introductory literature lesson, dedicated to introducing students to the textbook (according to the methodological development of the lesson system set out in the book: Turyanskaya B.I. and others. Literature in the 7th grade. Lesson after lesson. M.: Russian Word, 2000), students numbered the stanzas of the epic; in the above-mentioned textbook-reader, the epic is divided into twenty-two stanzas.

September 26, 2016The characterization of Volga Svyatoslavovich from the epic of the same name is usually compiled by students in a Russian literature lesson in the seventh grade. This hero has many positive qualities, and therefore it will not be difficult to describe him. Let's try to do this in more detail.

First appearance

The characterization of Volga Svyatoslavovich begins from the moment he first appears before the reader. From childhood, this prince showed himself to be a very educated and adventurous person. He is ready to learn to swim underwater like a fish, fly high like a bird, run through dark forests like a predatory wolf. This speaks of his activity and curiosity.

When the boy grew up and became a grown man, he decided to assemble a large squad for himself. He goes on a hike with her. His uncle Vladimir gave him an expensive gift: now Volga is the owner of three cities. The young man wanted to look at them and visit that area.

The brave squad was mounted on brown stallions by Volga Svyatoslavovich. The characterization of the hero continues with an analysis of his actions. The prince respects his warriors and does not spare them the best equipment and horses. However, his path is interrupted by a sudden acquaintance.

Mikula

Another main character of the epic appears before us. The prince is very surprised by his new acquaintance. He is so strong and brave that he plows a huge field alone. The characterization of Volga Svyatoslavovich from the epic should also include a description of Mikula. This brave guy does not look at all like an ordinary plowman: he is wearing expensive clothes, which are not at all typical of a peasant tiller. True, before meeting, the main characters could not reach each other for three days. By this the author wants to show how vast the vast expanses of our Motherland are.

Volga decided to talk to the Oratai, telling him where the path was heading. In response, Mikula told him about himself. It turns out that not so long ago he also visited the city where the prince was going. He bought salt for himself. The author uses the technique of hyperbolization and through Mikula’s mouth says that he is so strong that he had to drag three bags on himself, each containing one and a half tons of salt. Undoubtedly, Volga and his squad are very surprised by such strength of the hero.

However, not everything went well on that trip: robbers attacked Mikula and began to demand money. The hero shared with them, but it was not enough; they began to beat Oratai. Then Mikula Selyaninovich had to answer them. In the end, more than a thousand men were victims of one single plowman!

Undoubtedly, this story impressed Volga. Since childhood, he dreamed of having an unusual gift or power, but, unfortunately, this is not always within our power.

Then the prince decided to invite the hero with him on a campaign.

Characteristics of Volga Svyatoslavovich and his squad

Mikula is not averse to accompanying a new acquaintance on the road. But our farmer cannot just throw away the tool of his labor. His bipod, made of strong damask steel, is decorated with gold and silver. It is unlikely that we would have met an ordinary peasant with such a rich plow. But Mikula is the personification of all men in Rus'. For this reason, the author “dresses” him in expensive clothes, elegant morocco boots, and in his hands is a tool that only a hero can have.

The characterization of Volga Svyatoslavovich and Mikula Selyaninovich continues with an analysis of the episode with the prince’s squad. The hero asks Volga to send five warriors to help him and move the plow behind the willow bush. He wants to preserve it not for the poor or the rich, but for the simple Russian peasant.

The prince orders the guys to fulfill the request of the oratai. But, unfortunately, this turned out to be beyond their power.

Then Volga already sent ten warriors, but they could not cope with this.

Seeing that the squad cannot fulfill his request, Mikula himself decides to remove the bipod. This comes very easily to him: with one hand he lifts it and throws it in front of the surprised Volga.

Hike

The characterization of Volga Svyatoslavovich from the epic includes information about how he got to the desired city. The prince noticed that Mikula's horse was much faster and stronger than his own. He's a little depressed about this. Volga jokes with the hero that if his mare were a stallion, he would offer him as much as five hundred rubles for her. But Mikula does not want to part with her faithful friend under any circumstances and answers the prince that there is nothing more precious to him than this horse. He himself took care of it from a very young age, now he doesn’t need anyone else.

Upon arrival in the city, the prince was surprised that the men who had offended Mikula three days ago had gone to him to ask for forgiveness. Volga understands that Oratai is a good, kind and strong-willed person. He does not want to part with him, so he invites him to become a governor in his lands. This suggests that the prince is a grateful person who remembers kindness.

Conclusion

Of course, the characterization of Volga Svyatoslavovich is not as bright as that of the hero Mikula. Any warrior, even the strongest, pales against his background. However, we managed to find out that this person is friendly and responsive. He does not envy Mikula, but, on the contrary, wanted to be friends with him.