Theories of intelligence assume that the level of intelligence. The latest theories of intelligence. The main theories of intelligence include

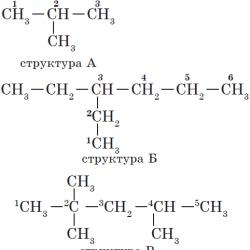

These theories claim that individual differences in human cognition and mental abilities can be adequately measured by special tests. Adherents of psychometric theory believe that people are born with different intellectual potential, just as they are born with different physical characteristics, such as height and eye color. They also argue that no amount of social programs can transform people with different mental abilities into intellectually equal individuals. There are the following psychometric theories presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Psychometric theories of personality

Let's consider each of these theories separately.

Ch. Spearman's two-factor theory of intelligence. The first work in which an attempt was made to analyze the structure of the properties of intelligence appeared in 1904. Its author, Charles Spearman, an English statistician and psychologist, creator of factor analysis, he drew attention to the fact that there are correlations between different intelligence tests: the one who performs well on some tests and turns out, on average, to be quite successful in others. In order to understand the reason for these correlations, C. Spearman developed a special statistical procedure that allows one to combine correlated intelligence indicators and determine the minimum number of intellectual characteristics that are necessary to explain the relationships between different tests. This procedure, as we have already mentioned, was called factor analysis, various modifications of which are actively used in modern psychology.

Having factorized various intelligence tests, C. Spearman came to the conclusion that correlations between tests are a consequence of a common factor underlying them. He called this factor “factor g” (from the word general - general). The general factor is crucial for the level of intelligence: according to the ideas of Charles Spearman, people differ mainly in the extent to which they possess the g factor.

In addition to the general factor, there are also specific ones that determine the success of various specific tests. Thus, the performance of spatial tests depends on the g factor and spatial abilities, mathematical tests - on the g factor and mathematical abilities. The greater the influence of factor g, the higher the correlations between tests; The greater the influence of specific factors, the weaker the connection between tests. The influence of specific factors on individual differences between people, as Ch. Spearman believed, is of limited significance, since they do not manifest themselves in all situations, and therefore they should not be relied upon when creating intellectual tests.

Thus, the structure of intellectual properties proposed by Charles Spearman turns out to be extremely simple and is described by two types of factors - general and specific. These two types of factors gave the name to Charles Spearman's theory - the two-factor theory of intelligence.

In a later edition of this theory, which appeared in the mid-20s, C. Spearman recognized the existence of connections between some intelligence tests. These connections could not be explained either by the g factor or by specific abilities, and therefore C. Spearman introduced to explain these connections the so-called group factors - more general than specific, and less general than the g factor. However, at the same time, the main postulate of Charles Spearman’s theory remained unchanged: individual differences between people in intellectual characteristics are determined primarily by general abilities, i.e. factor g.

But it is not enough to isolate the factor mathematically: it is also necessary to try to understand its psychological meaning. To explain the content of the general factor, C. Spearman made two assumptions. First, the g factor determines the level of “mental energy” required to solve various intellectual problems. This level is not the same for different people, which also leads to differences in intelligence. Secondly, factor g is associated with three features of consciousness - the ability to assimilate information (gain new experience), the ability to understand the relationship between objects and the ability to transfer existing experience to new situations.

C. Spearman's first assumption regarding the level of energy is difficult to consider as anything other than a metaphor. The second assumption turns out to be more specific, determines the direction of the search for psychological characteristics and can be used when deciding what characteristics are essential for understanding individual differences in intelligence. These characteristics must, firstly, correlate with each other (since they must measure general abilities, i.e. factor g); secondly, they can address the knowledge that a person has (since a person’s knowledge indicates his ability to assimilate information); thirdly, they must be associated with solving logical problems (understanding various relationships between objects) and, fourthly, they must be associated with the ability to use existing experience in an unfamiliar situation.

Test tasks related to the search for analogies turned out to be the most adequate for identifying such psychological characteristics. An example of such a task is shown in Figure 2.

The ideology of Charles Spearman's two-factor theory of intelligence was used to create a number of intellectual tests. However, already from the late 20s, works appeared that expressed doubts about the universality of the g factor for understanding individual differences in intellectual characteristics, and at the end of the 30s the existence of mutually independent factors of intelligence was experimentally proven.

Figure 2. Example of a task from the text by J. Ravenna

Theory of primary mental abilities. In 1938, Lewis Thurston's work “Primary Mental Abilities” was published, in which the author presented a factorization of 56 psychological tests diagnosing various intellectual characteristics. Based on this factorization, L. Thurston identified 12 independent factors. The tests that were included in each factor were taken as the basis for creating new test batteries, which in turn were conducted on different groups of subjects and again factorized. As a result, L. Thurston came to the conclusion that in the intellectual sphere there are at least 7 independent intellectual factors. The names of these factors and the interpretation of their content are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Independent intellectual factors

Thus, the structure of intelligence according to L. Thurston is a set of mutually independent and adjacent intellectual characteristics, and in order to judge individual differences in intelligence, it is necessary to have data on all these characteristics.

In the works of L. Thurston's followers, the number of factors obtained by factorizing intellectual tests (and, consequently, the number of intellectual characteristics that must be determined when analyzing the intellectual sphere) was increased to 19. But, as it turned out, this was far from the limit.

Cubic model of the structure of intelligence. The largest number of characteristics underlying individual differences in the intellectual sphere was named by J. Guilford. According to the theoretical concepts of J. Guilford, the implementation of any intellectual task depends on three components - operations, content and results.

Operations represent those skills that a person must demonstrate when solving an intellectual problem. He may be required to understand the information that is presented to him, remember it, search for the correct answer (convergent production), find not one, but many answers that are equally consistent with the information he has (divergent production), and evaluate the situation in terms of right - wrong , good bad.

The content is determined by the form in which the information is presented. Information can be presented in visual and auditory form, may contain symbolic material, semantic (i.e. presented in verbal form) and behavioral (i.e. discovered when communicating with other people, when it is necessary to understand from the behavior of other people how respond correctly to the actions of others).

Results - what a person ultimately comes to when solving an intellectual problem - can be presented in the form of single answers, in the form of classes or groups of answers. While solving a problem, a person can also find the relationship between different objects or understand their structure (the system underlying them). He can also transform the final result of his intellectual activity and express it in a completely different form than the one in which the source material was given. Finally, he can go beyond the information given to him in the test material and find the meaning or hidden meaning behind this information, which will lead him to the correct answer.

The combination of these three components of intellectual activity - operations, content and results - forms 150 characteristics of intelligence (5 types of operations multiplied by 5 forms of content and multiplied by 6 types of results, i.e. 5x5x6 = 150). For clarity, J. Guilford presented his model of the structure of intelligence in the form of a cube, which gave the name to the model itself. Each face in this cube is one of three components, and the entire cube consists of 150 small cubes, corresponding to different intellectual characteristics presented in Figure 3. For each cube (each intellectual characteristic), according to J. Guilford, tests can be created that will allow this characteristic to be diagnosed. For example, solving verbal analogies requires understanding verbal (semantic) material and establishing logical connections (relationships) between objects. Determining what is incorrectly depicted in Figure 4 requires a systematic analysis of the material presented in visual form and its evaluation. Conducting factor analytical research for almost 40 years, J. Guilford created tests to diagnose two-thirds of the intellectual characteristics he theoretically defined and showed that at least 105 independent factors can be identified. However, the mutual independence of these factors is constantly questioned, and the very idea of J. Guilford about the existence of 150 separate, unrelated intellectual characteristics does not meet with sympathy among psychologists involved in the study of individual differences: they agree that the entire variety of intellectual characteristics cannot be reduced to one general factor, but compiling a catalog of one hundred and fifty factors represents the other extreme. It was necessary to look for ways that would help organize and correlate the various characteristics of intelligence with each other.

The opportunity to do this was seen by many researchers in finding such intellectual characteristics that would represent an intermediate level between the general factor (factor g) and individual adjacent characteristics.

Figure 3. J. Guilford's model of the structure of intelligence

Figure 4. Example of one of J. Guilford's tests

Hierarchical theories of intelligence. By the beginning of the 50s, works appeared in which it was proposed to consider various intellectual characteristics as hierarchically organized structures.

In 1949, the English researcher Cyril Burt published a theoretical scheme according to which there are 5 levels in the structure of intelligence. The lowest level is formed by elementary sensory and motor processes. A more general (second) level is perception and motor coordination. The third level is represented by the processes of skill development and memory. An even more general level (fourth) are processes associated with logical generalization. Finally, the fifth level forms the general intelligence factor (g). S. Burt's scheme practically did not receive experimental verification, but it was the first attempt to create a hierarchical structure of intellectual characteristics.

The work of another English researcher, Philip Vernon, which appeared at the same time (1950), had confirmation obtained in factor analytical studies. F. Vernon identified four levels in the structure of intellectual characteristics - general intelligence, main group factors, secondary group factors and specific factors. All these levels are shown in Figure 5.

General intelligence, according to F. Vernon's scheme, is divided into two factors. One of them is related to verbal and mathematical abilities and depends on education. The second is less influenced by education and relates to spatial and technical abilities and practical skills. These factors, in turn, are divided into less general characteristics, similar to the primary mental abilities of L. Thurston, and the least general level forms features associated with the performance of specific tests.

The most famous hierarchical structure of intelligence in modern psychology was proposed by the American researcher Raymond Cattell. R. Cattell and his colleagues suggested that individual intellectual characteristics, identified on the basis of factor analysis (such as L. Thurston’s primary mental abilities or J. Guilford’s independent factors), with secondary factorization will be combined into two groups or, in the authors’ terminology, into two broad factors. One of them, called crystallized intelligence, is associated with the knowledge and skills that are acquired by a person - “crystallized” in the learning process. The second broad factor, fluid intelligence, has less to do with learning and more to do with the ability to adapt to unfamiliar situations. The higher the fluid intelligence, the easier a person copes with new, unusual problem situations.

Figure 5. F. Vernon's hierarchical model of intelligence

At first it was assumed that fluid intelligence was more closely related to the natural inclinations of intelligence and was relatively free from the influence of education and upbringing (its diagnostic tests were called culture-free tests). Over time, it became clear that both secondary factors, although to varying degrees, are still associated with education and are equally influenced by heredity. Currently, the interpretation of fluid and crystallized intelligence as characteristics of different natures is no longer used (one is more “social”, and the other is more “biological”).

During experimental testing, the authors' assumption about the existence of these factors, more general than primary abilities, but less general than factor g, was confirmed. Both crystallized and fluid intelligence have proven to be fairly general dimensions of intelligence that account for individual differences in performance on a wide range of intelligence tests. Thus, the structure of intelligence proposed by R. Cattell represents a three-level hierarchy. The first level represents primary mental abilities, the second level - broad factors (fluid and crystallized intelligence) and the third level - general intelligence.

Subsequently, with continued research by R. Cattell and his colleagues, it was discovered that the number of secondary, broad factors is not reduced to two. There are grounds, in addition to fluid and crystallized intelligence, for identifying 6 more secondary factors. They combine fewer primary mental faculties than fluid and crystallized intelligence, but are nonetheless more general than the primary mental faculties. These factors include visual processing ability, acoustic processing ability, short-term memory, long-term memory, math ability, and speed on intelligence tests.

To summarize the works that proposed hierarchical structures of intelligence, we can say that their authors sought to reduce the number of specific intellectual characteristics that constantly appear in the study of the intellectual sphere. They tried to identify secondary factors that are less general than the g factor, but more general than the various intellectual characteristics related to the level of primary mental abilities. The proposed methods for studying individual differences in the intellectual sphere are test batteries that diagnose psychological characteristics described by these secondary factors.

This is the oldest theory available. It was put forward by Charles Spearman at the beginning of the 20th century. He noticed that a person who successfully passed one IQ test , with a high degree of probability, another IQ test with a high result will pass, and vice versa - a person who scores low will receive it in all other similar tests. Based on this, he concluded that these tests could be used to determine mental abilities and the so-called “general intelligence” of people - which he designated by the letter “G” (from the English General - general, main). In addition to this, Spearman argued that each test also measures some other ability of a person - which he designated as S-intelligence - for example, vocabulary or mathematical ability. At the same time, Spearman believed that general intelligence is the basis of all intellectual actions.

Theory of primary mental abilities

In 1938, the American psychologist L. Thurstone suggested that intelligence includes 7 independent factors, which he called primary mental abilities:

- 1. The ability to listen and understand the meaning of what is heard

- 2. The ability to express your thoughts in words

- 3. Math ability

- 4. Memory

- 5. Speed of information perception

- 6. Reasoning skill

Theory of multiple intelligences

Proposed in 1983 by Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner. According to his ideas, there are several different intellects, independent of each other. According to this theory, each person has a certain combination of intelligences:

- 1. Linguistic intelligence

- 2. Logical-mathematical intelligence

- 3. Spatial intelligence

- 4. Musical intelligence

- 5. Physical-kinesthetic intelligence

- 6. Interpersonal intelligence

- 7. Deeply personal intelligence

Tripartite theory of intelligence

Proposed by R. Sternberg. According to this theory, there are three different types of intelligence. The first is analytical intelligence, which is a person’s ability to reason. The second type of intelligence - creative - is a person’s ability to use past experience to solve new problems. And the last, third type of intelligence - practical - reflects a person’s ability to successfully solve everyday life problems.

Psychometric theories of intelligence

They claim that

individual differences

V

human cognition

and mental abilities

can be adequately calculated by special tests

people are born with unequal intellectual potential

like that

how they are born with different physical characteristics:

Example:

height

eye color

no social programs can transform

people with different mental abilities

and in intellectually equal individuals

Ch. Spearman's two-factor theory of intelligence.

Author:

Charles Spearman

English

statistician

and psychologist

creator of factor analysis

States that:

There are correlations between different intelligence tests:

someone who performs well on some tests

turns out, on average, to be quite successful in other

Structure of intellectual properties

proposed by C. Spearman

described by two types of factors:

general

and specific

Hence the name:

two-factor theory of intelligence

Main postulate:

individual differences

between people

by intellectual characteristics

determined primarily by general abilities

Theory of primary mental abilities.

Designed by:

By whom?

Lewis Thurston

When?

In 1938

Where?

in the work “Primary Mental Abilities”

Based:

factorization of 56 psychological tests

diagnosing different intellectual characteristics

L. Thurston argued that:

Structure of intelligence

is a set

mutually independent

and nearby

and to judge individual differences in intelligence

it is necessary to have data on all these characteristics

In the works of L. Thurston's followers

number of factors

obtained by factorizing smart tests

(and consequently

and the number of intellectual characteristics

which must be determined when analyzing the intellectual sphere)

was increased to 19

But, as it turned out, this was far from the limit.

Cubic model of the structure of intelligence.

The model has the largest number of characteristics

underlying

individual differences in the intellectual sphere

Author:

J. Guilford

States that:

The execution of any intellectual task depends on three components:

operations

those. those skills

which a person must demonstrate when solving an intellectual problem

content

determined by the form of information submission

Example:

in the shape of:

visual

auditory

in the form of material

symbolic

semantic

presented in verbal form

behavioral

discovered when communicating with other people

when it is necessary to understand from the behavior of other people

how to react correctly to the actions of others

and results

what a person ultimately comes to

intellectual problem solver

which can be presented

in the form of single answers

as

classes

or groups

answers

Solving the problem

human can

find the relationship between different objects

or understand their structure

(the system underlying them)

or transform the final result of your intellectual activity

and express it

in a completely different form

than that

in which the source material was given

go beyond that information

which is given to him in the test material

and find

meaning

or hidden meaning

underlying this information

which will lead him to the correct answer

The combination of these three components of intellectual activity

operations

content

and results

- forms 150 intelligence characteristics

5 types of operations

multiply by 5 forms of content

and multiply by 6 types of results

For clarity, J. Guilford presented his model of the structure of intelligence

in the form of a cube

which gave the model its name

Criticism:

questioned

mutual independence of these factors

like the very idea of existence 150

intellectual characteristics

individual

not related to each other

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru/

Course work

General psychology

Topic: Psychological theories of intelligence

Seryachenko Victoria

Introduction

Conclusion

Glossary

Introduction

The versatility of intelligence is one of the reasons why theorists find it difficult to define this phenomenon. Some pioneers in the study of intelligence, in an attempt to uncover some of the underlying components of this phenomenon and recognizing its complex nature, used factor analysis, a statistical method designed to determine the source of variation in correlation measures. The most commonly used experimental paradigm involves administering a battery of tests, each of which can measure one specific attribute of intelligence, such as reasoning, mathematical ability, spatial ability, or vocabulary. In factor analysis of test scores, typically collected from a large, representative sample, the correlations between all subscales are measured and the factors underlying individual test performance are then determined.

The most famous of these early scientists is Charles Spearman, who proposed that intelligence consists of a “g,” or general factor, and “s,” or a set of specific factors involved in individual mental abilities. According to Spearman, intelligence is best characterized in terms of a single latent factor that dominates test scores. Thus, a person might show unusually high ability in one or more specific factors and show poor ability in other factors. Other theorists, including Thurstone, suggest that intelligence is best thought of as a combination of several factors, which he called "primary mental abilities." Guilford expanded the concept of factor analysis to include the logical analysis of factors involved in mental functions. His system, called the "structure of intelligence," proposes an even more complex mosaic of the components of intelligence. All mental abilities are represented here as a three-dimensional network, which originally contained 120 factors and was later expanded to 150. In this network, one axis is the operations required to perform functions such as divergent and convergent thinking, memory and cognition (thinking). ; along the second axis there are such products of mental operations as connections, systems, transformations and consequences; and on the third axis are the specific contents of the tasks - figurative, semantic, symbolic or behavioral.

Increasing the number of factors that measure the facet of human intelligence may help identify the complex nature of this phenomenon; yet some theorists argue that such techniques are prone to unnecessary excess and that the hierarchical model is more elegant. Such a system was proposed by Cattell. In his system, general intelligence consists of two main subfactors: “fluid abilities” and “crystallized abilities.” Fluid abilities provide understanding of abstract and sometimes novel relationships and are evident in inductive reasoning, analogies, and sequence completion tests. Crystallized abilities are associated with the accumulation of facts and general knowledge and manifest themselves in tests of vocabulary and general awareness.

The factor analytic approach to human intelligence has certainly expanded our understanding of this complex phenomenon, but cognitive psychologists have set a dangerous ambush on the path blazed by Spearman, Thurstone, Guilford, and Cattell. Robert Sternberg of Yale University argues that the method of studying intelligence using factor analysis is causing growing skepticism for the following reasons:

The factor analysis method is loosely related to “mental processes”; for example, two people might score identically on an intelligence (IQ) test but use different cognitive processes.

Factor analysis techniques and models are difficult to test by pitting them against each other. Trying to understand intelligence in terms of individual characteristics, on which the logic of factor analysis primarily relies, is not the only (and not necessarily the best) means available for analyzing human abilities.

Later, cognitive psychologists proposed both new methods and new models of human intelligence, generally consistent with the information approach.

If information processing goes through successive stages, each of which carries out unique operations, then the human mind can be viewed as a component of human intelligence that interacts with information processing. In essence, this is exactly how cognitive psychologists who adhere to the information approach to cognition imagine the human mind. Enthusiasm for the information approach seems to have begun when cognitive psychologists became fascinated by computer intelligence. The analogy between human and artificial intelligence is inevitable; information from the external world is perceived or “entered”, it is stored in memory, undergoes a certain transformation, and then an “output” is produced. In addition, information processing is similar to computer programs and human intellectual functions, including the mind.

Cognitive theories of intelligence suggest that intelligence is a component that interacts with information at various stages of processing in which unique operations are performed. Research based on this view has determined that memory retrieval (speed, accuracy, and quantity) is a function of verbal ability, and that an individual's stock of knowledge (novice or expert) influences the quantity and accuracy of retrieval, as well as the accuracy of his or her metamemory.

1. Concepts and definitions of intelligence

Intelligence is the system of an individual's cognitive abilities. Intelligence is most obviously manifested in the ease of learning, the ability to quickly and easily acquire new knowledge and skills, in overcoming unexpected obstacles, in the ability to find a way out of an unusual situation, the ability to adapt to a complex, changing, unfamiliar environment, in the depth of understanding of what is happening, in creativity. The highest level of development of intelligence is determined by the level of development of thinking, considered in unity with other cognitive processes - perception, memory, speech, etc. We can point to several, now traditional, areas of intelligence research. First of all, this is the study of the structure of intelligence, those basic cognitive abilities (factors), the interaction of which forms intelligence as a single whole. A very representative area is the one for which the main problem is the measurement of intelligence. Moreover, if intelligence is considered as the ability to effectively solve various cognitive tasks, then it is natural that the efforts of researchers are aimed at developing a system of such tasks along with a system of indicators for assessing their implementation. There are currently relatively many known tests for measuring certain intellectual abilities (Eysenck tests (Appendix A), Wechsler, Guilford, Rowen, etc.). The study of human intellectual development in ontogenesis is very significant in theoretical and practical terms. Qualitatively different levels of intellectual development are determined (Piaget). Age norms for the development of various intellectual abilities are studied (A. Wiene, T. Simon), which allows us to consider the advanced intellectual development of a child as an excess of his intellectual level over the level of intellectual development typical for a child of this age. For example, the intellectual giftedness of a child at an early age usually manifests itself in the development of speech (vocabulary, complexity of form, content), memory, and the ability to concentrate attention for unusually long periods of time, which exceeds age norms. Research directly aimed at creating artificial intelligence is also very interesting.

Intelligence, more than any other concept in psychology, has been the subject of controversy and criticism. Already when trying to define intelligence, psychologists encounter significant difficulties. In 1921, the journal Educational Psychology organized a discussion in which leading American psychologists took part. Each of them was asked to define intelligence and name a way in which intelligence could best be measured. Almost all scientists named testing as the best way to measure it, while their definitions of intelligence turned out to be paradoxically contradictory. A very successful metaphor in this regard was given by V.N. Druzhinin. in his book: Diagnostics of general abilities. He writes: “The term “intelligence,” in addition to its scientific meaning (which each theorist has its own), like an old cruiser with shells, has become overgrown with an endless number of everyday and popular interpretations. Listing all currently available definitions of intelligence does not make sense within the framework of this work - To understand the concept being studied, it is advisable to review the most generally accepted interpretations. When they talk about intelligence as a certain ability, many scientists primarily rely on its adaptive significance for humans and higher animals. For example, V. Stern believed that intelligence is some general ability to adapt to new living conditions. And according to L. Polanyi, intelligence refers to one of the ways of acquiring knowledge. But, in the opinion of most other authors, the acquisition of knowledge (assimilation, according to Piaget J) is only a side aspect of the process of applying knowledge when solving life task It is important that the task is truly new or at least has a component of novelty. Closely related to the problem of intellectual behavior is the problem of “transfer” - the transfer of “knowledge - operations” from one situation to another (new). But in general, developed intelligence, according to J. Piaget, manifests itself in universal adaptability, in achieving “equilibrium” of the individual with the environment. Any intellectual act presupposes the activity of the subject and the presence of self-regulation during its implementation. According to Akimova M.K., the basis of intelligence is precisely mental activity, while self-regulation only provides the level of activity necessary to solve a problem. Golubeva E.A. adheres to this point of view, believing that activity and self-regulation are the basic factors of intellectual productivity, and adds working capacity to them. Thus, we can give a primary definition of intelligence as a certain ability that determines the overall success of a person’s adaptation to new conditions. The mechanism of intelligence manifests itself in solving a problem in the internal plane of action (“in the mind”) with the dominance of the role of consciousness over the unconscious. However, such a definition is as controversial as all others. Thompson J. believes that intelligence is only an abstract concept that simplifies and summarizes a number of behavioral characteristics. The scientists who developed the first intelligence tests (for example, Binet, Simon, 1905) considered this property more broadly. In their opinion, a person with intelligence is one who “correctly judges, understands and reflects” and “who, thanks to his common sense” and “initiative”, can “adapt to the circumstances of life.” Wexler shared this point of view - he believed that “intelligence is the global ability to act intelligently, think rationally and cope well with life circumstances.” The lack of unambiguity in the definitions of intelligence is due to the diversity of its manifestations. However, all of them have something in common that allows them to be distinguished from other behavioral features, namely the activation in any intellectual act of thinking, memory, imagination - all those mental functions that provide knowledge of the surrounding world. Accordingly, some scientists, by intelligence as an object of measurement, mean those manifestations of a person’s individuality that are related to his cognitive properties and characteristics. This approach has a long tradition. However, understanding intelligence as the ability to learn, it is thereby tied to the tasks of only one type of activity. In addition, there are other reasons that do not allow us to accept this definition of intelligence. Indeed, many studies have shown that data obtained using intelligence tests significantly correlate with educational success (the correlation coefficient is approximately 0.50, and the dependence is higher in the early grades of school, and then decreases slightly). But performance assessments reflect not the process of learning, but its result, and the correlations themselves are explained by the fact that most intelligence tests measure “the extent to which an individual has the intellectual skills that are learned in school.” But neither intelligence tests nor school assessments can predict how a person will cope with many life situations. There is no generally accepted definition of this term in psychology, since there is no generally accepted theory of intelligence. Psychologists are still arguing about its nature. Currently, there are many theories of intelligence. One of the attempts to organize the information accumulated in the field of experimental psychological theories and research on intelligence belongs to M.A. Cold. She identified eight main approaches, each of which is characterized by a certain conceptual line in the interpretation of the nature of intelligence.

2. Formation of ideas about intelligence in the history of philosophy

The origins of two alternative traditions of theorizing regarding the concept of intelligence are found already in antiquity. The origins of the dialectical tradition of theorizing include Anaxagoras’s doctrine of “nous”, which was the first idea of the intellect in philosophy, revealing the unity of two ideas of the mind: as a conscious, spiritual force that determines the order of everything and as a combining force, i.e. creative mind.

The reflection of reality in Plato's works is revealed as a reproduction of reality through sensory images. In this case, eidos is shown as an essence mediated in a sensory image. The soul in Plato's teaching is presented as a part of the world of true existence; it by nature belongs to the world in which the eidos exist, and participates in them not in an external, but in an essential way. It is noted that the mind as a part of the soul for Plato serves as a certain tool for comprehending true existence and each person has different strength, which explains the formation of knowledge at different levels. A degenerate form of knowledge according to Plato is opinion, which is a guess about reality.

Aristotle (one of the founders of the dialectical tradition) was the first to theoretically substantiate intelligence as similarity to the world of things through sensory forms - images of the objective world, and was also one of the first to apply an essential research approach to the study of intelligence. He identified two main traditions of philosophical theorizing. According to one of them (sophist), the matter comes down to comprehending the world through arbitrarily formed schemes based on human free will. At the same time, it is accepted that it is possible to rebuild the world in accordance with these patterns and human needs. This trend was first set by the Sophists. Another tradition was set by the dialecticians of antiquity. According to the latter, there was an understanding of the need to know the objective laws of development of nature, society and thinking, i.e. knowledge of the laws under which everything flows and everything changes. In the system of these two traditions, the comprehension of the phenomenon of intellect from the points of view of metaphysics and dialectics is further developed.

During the Middle Ages, in the metaphysical system of theorizing, a discussion opens between nominalists and realists, the essence of which is to study the nature of concepts and thereby the nature of intellect: according to nominalists, intellect is only capable of naming objects, but according to realists, intellect operates with eternal concepts. Subsequently, within the framework of the metaphysical system of theorizing, the realist and nominalist versions of the study of intelligence received constructive development, taking the forms of neonominalism and neorealism.

Medieval views on the nature of intelligence were replaced by the rationalistic views of the Renaissance. Philosophers of this period endowed nature with the properties of some intelligently designed machine, similar to a clock mechanism, as, for example, N. Kuzansky: “The machine of the world cannot wear out and die.” Therefore, they believed, it was quite possible to know it through the laws of mechanics. The phenomenon of intelligence in Western philosophy received its final theoretical-representational design in the modern era in the 16th-17th centuries, when the results of experimental natural science became the basis for theorizing. During this period, scientists gained knowledge about the surrounding reality through observation and experiment, and the study of intelligence developed on the basis of a universalist model of the world. In the modern era, intelligence was revealed as something designed to serve the growing needs of the material, production and economic spheres of society, as F. Bacon writes: “The goal of our society is to know the causes and hidden forces of all things and to expand man’s power over nature until everything becomes possible for him." The utilitarian attitude in cognition is set by the standards of the model of the world as a Universe. R. Descartes also, based on the universalist model of the world, formulates the well-known principle “cogito ergo sum”, thereby defining man as a purely epistemological subject, the whole essence of which consists only in thinking. R. Descartes’ intellect is completely turned towards itself, therefore for there is nothing easier for him than to know his intellect: “Once I realized that bodies themselves are perceived, in fact, not with the help of the senses or the faculty of imagination, but only by the intellect, and they are perceived not because I directly declare: nothing can be perceived by me with greater ease and obviousness than my mind."

Intellect as a representation of the world received a fundamental generalization in the modern era in the works of the outstanding German philosopher I. Kant, who conducted a detailed analysis of the nature of intelligence. Kant's study of intellect is based on the concept of "transcendental reality", according to which reality is unknowable, since it exists before knowledge and does not depend on it. Knowledge as a product of cognitive activity is delimited from reality, represented in Kant’s works by “things in themselves.” Objects remain accessible to the intellect only as noumena, which form an imagined, transcendental reality.

Positivists, based on Western traditions of studying intelligence, as well as with increasing scientific and technological progress, developed the study of intelligence on the basis of purely applied branches of knowledge, the first page was opened by O. Comte and G. Spencer. Experienced knowledge becomes for them the only valuable type of knowledge that can give an idea of reality.

The natural-scientific attitude of the positivists is the reason for the psychologization of cognition, since cognitive actions are attributed in it to the “empirical” and not the “transcendental” intellect. Cognition appears as an adaptation to reality, the result of which is the registration of functional connections between experimental data through the human psyche. The task of the intellect is reduced in this case to the creation of mental constructs that represent reality in the human mind. On this theoretical basis is built the point of view of E. Husserl, for whom the intellect of each subject forms its own phenomenon of the world. Reality is represented by a set of intuitively formed autonomous phenomena that are descriptive in nature and do not have universality, which the author defines as a transition from the neorealist direction to the neonominalist one. The presence of a plurality of world-versions (phenomena according to Husserl) is explained in the works of M. Wartofsky by the presence of “internal representation”, which, in his opinion, is an even more complex and controversial phenomenon, since it includes such components as creativity, transmission and storage meanings, spiritual activity of imagination, reflection and will. The internal, autonomous nature of representation was also identified by the dissertation candidate in the works of another modern Western philosopher H.Y. Sandkühler, who recognizes that “being in itself does not represent itself in us; representation has a completely different status and a different function, it is the presentation of the content of representations in others and through other contents. What people perceive, they must first imagine; and They do both in themselves and through themselves.”

The theory of cognition as a theory of reality representation distinguishes the traditions of research into intelligence in the context of a universalist model of the world from research into intelligence in the context of a cosmic model of the world, in which the study of intelligence is developed on the basis of the theory of cognition as a theory of reflection. At the same time, the standard of theorizing is determined by dialectics. The characteristics of intelligence formulated by I. Kant are reflected in a number of philosophical directions in the development of Western philosophy of the 19th and 20th centuries: in positivism (O. Comte, G. Spencer), phenomenology (E. Husserl), hermeneutics (H.-H. . Gadamer), pragmatism (C. Pierce, J. Dewey), etc., revealing the absolute right of the dominant position of the intellect in the system “sensibility - reason - reason”. The form of proof of the truth of knowledge in this system of theorizing is formal logic, focused on the axiomatic form of expression of thought, i.e. laws of linguistic reality, defined by an arbitrarily defined composition of concepts, axioms and rules of inference, according to which Kant’s invented transcendental reality, doubling the world, unfolds.

The tradition of studying intelligence, laid down by ancient dialecticians (Anaxagoras, Plato, Aristotle), was adopted and developed by Byzantine philosophers (Proclus, D. Areopagite, I. Damascene, F. Studite, M. Confessor, etc.). The achievements of the Byzantines in the field of intelligence were developed in Russian philosophy, starting with John the Sinful, the philosophical school of Sergius of Radonezh (I. Volotsky, N. Sorsky, Z. Ottensky) and continuing with research into the intelligence of Russian thinkers of the 18th century (M.V. Lomonosova, A. N. Radishchev), later - Slavophiles (A.S. Khomyakov, I.V. Kireevsky), within the framework of the same cosmic model of the world. It is noted that domestic thinkers following the Slavophiles were unable to avoid the influence of European philosophy, which is found in their studies of intelligence. The principle of the universal connection of phenomena in Byzantine philosophy is presented in the concept of the Holy Trinity as a single divine essence, revealing its existence in three hypostases. In this case, hypostasis acts as the mediated existence of the divine essence, i.e. existence of an entity. Therefore, in Byzantine philosophy, the human mind represents the existence of the perfect essence of God. In this regard, exploring the etymology of the word “God”, John of Damascus considers one of the options to be Iept (Greek to run), which proves the presence (existence of a perfect divine essence) of God in everything, including in the mind of man, in which, thanks to this property God enters as Truth and creative power. The perfection of the divine essence, on the one hand, ensures the objectivity of knowledge as its existence in the human mind, and on the other hand, perfect reason as the image of the perfect essence of God is the creative principle in the human intellect, since God is the source of new knowledge. As Proclus notes: “Every divine mind is one in appearance and perfect and is the primary mind, producing from itself other minds.” These theoretical positions were developed by ancient Russian philosophers and received further substantive development. "Izbornik 1076" is one of the first written sources in Rus' that testified to the inheritance of the Byzantine philosophical tradition by ancient Russian thinkers. The author of this work was John the Sinner, who wrote: “Believe in the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, in the indivisible Trinity, one Divinity, the Father is not begotten, the Son is begotten, but not given, the Holy Spirit is neither begotten, not given, but also descends - three - one will, one glory, one part."

Belarusian philosophy also identifies a number of thinkers who contributed to the development of the dialectical tradition of the study of intelligence, including Francis Skorina and Simeon of Polotsk. The works of ancient Russian and Belarusian philosophers were consigned to oblivion, since the world and Russian public preferred the universalist model of the world, and, consequently, Western theorizing. In the 18th and 19th centuries, with the general enthusiasm for metaphysical theorizing, the dialectical tradition of studying intelligence in the system of the cosmic model of the world was not lost. This tradition was continued in the 18th century by F. Prokopovich, M.V. Lomonosov, A.N. Radishchev, in the 19th century - Slavophile philosophers I.V. Kireevsky, A.S. Khomyakov, in the 20th century - L.P. Karsavin, A.F. Losev et al.

Soviet philosophers, on the basis of dialectical materialism, continued the study of intelligence in the dialectical system of theorizing. They based the study of intelligence on the relationship between the ideal and the material, recognizing the primacy of the latter. Based on the theory of knowledge as a theory of reflection, they not only substantiated the knowability of reality, but also turned dialectics into a strict and harmonious method of philosophical knowledge of the world.

On this basis, they showed the activity of the intellect as a creative reflection of reality and revealed that the intellect is a subjective image of reality in the process of cognition, revealing the laws of development of nature, society and thinking: “The development of our thinking is only a reflection of objective dialectics, the laws of thinking are a reflection of the laws of nature ".

At the present stage, in the dialectical system of philosophical theorizing, the study of the phenomenon of intelligence continues.

intelligence psychology individual abstract

3. Basic approaches in psychology to the formation of intelligence

There are eight main approaches to the formation of intelligence, each of which is characterized by a certain conceptual line in the interpretation of the nature of intelligence.

1. Phenomenological approach: intelligence is considered as a special form of the content of consciousness (W. Keller; K. Duncker; M. Wertheimer; J. Campion, etc.).

2. Genetic approach: intelligence as a consequence of increasingly complex adaptation to environmental requirements in the natural conditions of human interaction with the outside world (W.R. Charlesworth; J. Piaget).

3. Sociocultural approach: intelligence as a result of the socialization process, as well as the influence of culture as a whole (J. Brunner; L. Levy-Bruhl; A.R. Luria; L.S. Vygotsky, etc.).

4. Process-activity approach: intelligence as a special form of human activity (S.L. Rubenstein; A.V. Brushlinsky; L.A. Wenger; K.A. Abulkhanskaya-Slavskaya, etc.).

5. Educational approach: intelligence as a product of targeted learning (A. Staats; K. Fischer; R. Feuerstein, etc.).

6. Information approach: intelligence as a set of elementary processes of information processing (G. Eysenck; E. Hunt; R. Sternberg, etc.).

7. Functional-level approach: intelligence as a system of multi-level cognitive processes (B.G. Ananyev; E.I. Stepanova; B.M. Velichkovsky, etc.).

8. Regulatory approach: intelligence as a factor in the self-regulation of mental activity (L.L. Thurstone et al.).

Phenomenological approach. On the one hand, Köller argued that there are forms in the visual field that are directly determined by the characteristics of the objective situation. On the other hand, he noted that the form of our images is not a visual reality, since it is rather a rule for the organization of visual information, born within the subject. The assertion that the mental image actually suddenly restructures itself in accordance with the objectively valid “law of structure” essentially meant that an intellectual reflection is possible on the extra-intellectual activity of the subject himself. One of the first attempts to construct an explanatory model of intelligence was presented in Gestalt psychology. The prerequisites for this approach were set by W. Köller. As a criterion for the presence of intellectual behavior in animals, he considered the effects of structure: the emergence of a solution is due to the fact that the field of perception acquires a new structure, which captures the relationships between the elements of the problem situation that are important for its resolution. The decision itself arises suddenly; this phenomenon is called insight.

Subsequently, M. Wertheimer, characterizing the “productive thinking” of a person, also brought to the fore the processes of structuring the content of consciousness: grouping, centering, reorganization of available impressions. The main vector along which the image of the situation is being restructured is its transition to an extremely simple, clear, dissected, meaningful image, in which all the main elements of the problem situation are fully reproduced. A sign of the involvement of the intellect in the work is such a reorganization of the content of consciousness, thanks to which the cognitive image acquires the “quality of form.” In Gestalt psychology, the structuring features of the phenomenal visual field subsequently turned out to be reduced to the action of neurophysiological factors. Thus, the extremely valuable idea that the essence of intelligence lies in its ability to generate and organize the subjective space of cognitive reflection was completely lost for explanatory psychological analysis. A special place in Gestalt psychological theory was occupied by the research of K. Duncker. He believed that the deeper the insight, that is, the more essential features of the problem situation determine the response action, the more intellectual it is. According to Duncker, the deepest differences between people in what we call mental giftedness have their basis precisely in the greater or lesser ease of reconstructing mental material. That. the ability for insight (i.e. the ability to quickly rearrange the content of a cognitive image in the direction of identifying the main problematic contradiction of the situation) is a criterion for the development of intelligence.

Genetic approach. Ethological theory of intelligence. According to U.R. Charlesworth, a proponent of the ethological approach in explaining the nature of intelligence, is a way of adapting a living being to the requirements of reality, formed in the process of evolution. For a better understanding of the adaptive functions of intelligence, he proposes to distinguish between the concept of “intelligence,” which includes existing knowledge and already formed cognitive operations, and the concept of “intellectual behavior,” which includes means of adaptation to problem situations, including cognitive processes that organize and control behavior. A look at intelligence from the perspective of the theory of evolution led Charlesworth to the conclusion that the deep mechanisms of that mental property that we call intelligence are rooted in the innate properties of the nervous system.

Operational theory of intelligence. According to J. Piaget, intelligence is the most perfect form of adaptation of the organism to the environment, representing the unity of the process of assimilation and the process of accommodation. That. the essence of intelligence lies in the ability to carry out flexible and at the same time stable adaptation to physical and social reality, and its main purpose is to structure (organize) a person’s interaction with the environment. The development of intelligence is a spontaneous process, subject to its own special laws, of the maturation of operational structures (schemes) that gradually grow out of the child’s objective and everyday experience. According to Piaget's theory, this process can be divided into five stages. Stage of sensorimotor intelligence (from 8-10 months to 1.5 years). Symbolic or pre-conceptual intelligence (from 1.5 years to 4 years).

Stage of intuitive (visual) intelligence (from 4 to 7-8 years). Stage of specific operations (from 7-8 to 11-12 years). Stage of formal operations, or reflective intelligence (from 11-12 to 14-15 years).

Consequently, intellectual development is the development of the operational structures of the intellect, during which mental operations gradually acquire qualitatively new properties: coordination, reversibility, automatization, and reduction. In the development of intelligence, according to Piaget's theory, there are two main lines. The first is associated with the integration of operational cognitive structures, and the second is associated with the growth of invariance (objectivity) of individual ideas about reality.

Sociocultural approach. A statement that a person is formed as a cultural and historical being, assimilating in the course of his life material and spiritual values created by other people. There is also the fact that such sociocultural factors as language, industrialization, education, family institution, customs, traditions, etc., are determinants in relation to the level and pace of mental (in particular intellectual) development of all members of society. The specific task of intercultural research was a comparative analysis of the characteristics of the intellectual activity of representatives of different cultures.

Process-activity approach. L.S. Rubenstein emphasized that the psyche as a living real activity is characterized by processuality, dynamism, and continuity. Accordingly, the mechanisms of any mental activity are formed not before the start of the activity, but precisely in the process of the activity itself. That. the possibility of mastering (appropriating) from the outside any knowledge, ways of behavior, etc. presupposes the presence of certain internal prerequisites. According to Rubinstein, the core, or general, main component of any mental ability is the quality of the processes of analysis, synthesis and generalization inherent in a given person. Consequently, the essence of intellectual education of a person lies in the formation of a culture of those internal processes that underlie a person’s ability to constantly arise new thoughts, which, in fact, serves as the most obvious criterion for the level of intellectual development. Experimental studies of the mechanisms of intellectual activity have also been carried out. Personal factors are considered as such mechanisms: operational meanings, emotions, motives, goal setting. For a person, the same element of a problem situation appears differently for him at different stages of the solution process. It turned out that, arising before a decision is made, emotional activation contributes to fixing the search area, narrowing its volume, and changing the nature of search actions. It also became known that as personally significant motivation increases, indicators of productivity and originality of answers increase. Cognitive activity at any level (perception, memory, thinking, etc.) is influenced by a variety of personal factors. The specific role of the intellect is that the intellect “produces” such subjective states that do not depend on the characteristics of the cognizing subject and are a condition for the objectification of all aspects of his cognitive activity.

Educational approach. Intelligence can be studied through the formation of certain cognitive skills in specially organized conditions with targeted external guidance of the process of mastering new forms of intellectual behavior. In studies of social-behaviourist orientation, intelligence is considered as a set of cognitive skills, the acquisition of which is a necessary condition for intellectual development. Intelligence here is interpreted as a “basic behavioral repertoire” acquired through certain learning procedures. R. Feuerstein understood intelligence as a dynamic process of human interaction with the world, therefore the criterion for the development of intelligence is the mobility of individual behavior. If a child develops in favorable family and sociocultural conditions, then such experience accumulates in him naturally, as a result of which the child adapts relatively effectively to his environment. According to Feuerstein, the development of intelligence with age is a function of mediated learning experience, or more precisely, its influence on the child’s cognitive abilities.

Z.I. Kalmykova proposes to define the nature of intelligence through “productive thinking,” the essence of which is the ability to acquire new knowledge. The “core” of individual intelligence, in her opinion. They constitute a person’s ability to independently discover new knowledge and apply it in non-standard problem situations. It is also necessary to pay attention to the “zones of proximal development” and their features regarding the development of intelligence. Here two lines of training should be distinguished: a) active learning zone; b) the child’s zone of creative independence.

Information approach. According to G. Eysenck, the way to prove the existence of intelligence is to prove its neurophysiological determination. The main point is that individual IQ differences are directly caused by the functioning of the central nervous system, which is responsible for the accuracy of the transmission of information encoded as a sequence of nerve impulses in the cerebral cortex. If this kind of transfer in the process of information processing from the moment of exposure to a stimulus to the moment of formation of a response is carried out slowly, with glitches and distortions, then success in solving test problems will be low. To understand the nature of intelligence, the “mental speed” component is especially important, which, according to Eysenck, is the psychological basis and source of intelligence development. E. Hunt and R. Sternberg are convinced that a person’s intellectual capabilities cannot be described by a single IQ indicator and that IQ as the sum of scores on a certain set of tests is more of a statistical convention than an indicator of individual intelligence. Here it is believed that elementary information processes are micro-operational cognitive acts associated with the operational processing of information.

Functional-level approach. A number of essential provisions regarding the nature of human intellectual capabilities are formulated within the framework of the theory of intelligence, developed under the leadership of B.G. Ananwa. The main idea was that intelligence is a complex mental activity, representing the unity of cognitive functions of different levels.

Studying the nature of intrafunctional and interfunctional connections made it possible to obtain a number of facts characterizing the features of the organization of intellectual activity at different levels of cognitive reflection.

A number of important conclusions were also made regarding the functional-level structure of intelligence.

1. There is a system of influences of higher levels of cognitive reflection on lower ones and lower ones on higher ones, i.e. we can talk about the emerging system of cognitive syntheses “from above” and “from below”, which characterize the structure and patterns of development of human intelligence.

2. Intellectual development is accompanied by a tendency to increase the number and magnitude of correlations both between different properties of one cognitive function, and between cognitive functions of different levels. This fact was interpreted as a manifestation of the effect of integration of different forms of intellectual activity and, accordingly, as an indicator of the formation of an integral structure of intelligence at the stage of adulthood (18 - 35 years).

3. With age, there is a rearrangement of the main components in the structure of intelligence. In particular, at 18-25 years of age, the most powerful indicator, according to correlation analysis, is the indicator of long-term memory, followed by the indicator of verbal-logical thinking. However, at 26-35 years old, indicators of verbal-logical thinking come first, followed by indicators of attention, and only then - indicators of long-term memory.

4. There are cross-cutting properties inherent in all levels of cognitive reflection: a) volumetric capabilities; b) the unity of the sensory (figurative) and logical as the basis for the organization of any cognitive function; c) orientation regulation in the form of the severity of attention properties. In general, we can say that the criterion for the development of intelligence, according to this direction, is the nature of intra- and interfunctional connections of various cognitive functions and, in particular, the measure of their integration.

Regulatory approach. The position that intelligence is not only a mechanism for processing information, but also a mechanism for regulating mental and behavioral activity. This theory was formulated and substantiated in 1924 by L.L. Thurstone, he talked about the difference between reason and reason. He considered intelligence as a manifestation of rationality as the ability to inhibit impulsive impulses or suspend their implementation until the initial situation is understood in the context of the most acceptable mode of behavior for the individual. Unintellectual behavior is characterized by an orientation towards any solution that is at hand. Intelligent behavior presupposes:

1) the ability to delay one’s own mental activity at different stages of preparation for a behavioral act.

2) the ability to think in different directions, making a mental choice among many more or less suitable options for adaptive behavior.

3) the ability to comprehend the situation and one’s own motives at a general level based on the connection of conceptual thinking.

The main criterion of intellectual development in the context of this theory is the measure of need control. According to R. Zions, the process of emotional assessment of the displayed aspects of reality is, in comparison with the process of their comprehension, some parallel psychological reality, living according to its own laws. It can also be noted that the criterion of intellectual maturity will be the subject’s readiness to accept any event as it is in its objective reality, as well as his readiness to change the original motives, creating derivative needs, turning goals into means, taking into account the objective requirements of activity, etc. . On the contrary, a low level of intellectual maturity will apparently initiate certain types of defensive behavior against the backdrop of vigorous, albeit very unique, intellectual activity.

And in conclusion, we can say that regarding the ways people use their intelligence, research in this area is far from complete. Moreover, people sometimes use their intelligence in the most unexpected, if not paradoxical, way.

Conclusion

The concepts discussed above do not fully reveal the concept of “intelligence” - they only allowed us to come closer to the understanding that intelligence, as a phenomenon, is on the border between the individual-typical characteristics of a person and psychological processes and states. Such versatility of this phenomenon gives grounds for the conclusion that for every branch of psychology or philosophy that, in one way or another, deals with problems of intelligence (for example: psychophysiology, differential psychology, general psychology, psychodiagnostics, anthropology, etc.), it will be true its own definition, formed within the framework of the subject and method of this branch, based on the classical interpretation of this term, which comes from the Latin intellectus - knowledge, understanding, reason. The Latin translation of the Greek concept nus - “mind”, is identical to it in meaning. An important point here should be clarified that intelligence is the ability to adapt on the basis of rational activity. This is its fundamental difference from other adaptive mechanisms of the nervous system, and distinguishes it from a more general construct of thinking - general abilities. The entire history of the world, based on brilliant guesses, inventions and discoveries, testifies that man is certainly intelligent. However, the same story provides numerous evidence of the stupidity and madness of people.

On the one hand, the ability for rational cognition is a powerful natural resource of human civilization. On the other hand, the ability to be reasonable is the thinnest psychological shell, instantly discarded by a person under unfavorable conditions.

The purpose of intellect is to create order out of chaos based on matching individual needs with the objective requirements of reality. Blazing a hunting trail in the forest, using constellations as landmarks on sea voyages, prophecies, inventions, scientific discussions, etc., that is, all those areas of human activity where you need to learn something, do something new, make a decision, understand, explain, discover - all this is the sphere of action of the intellect. Intelligence is like health: when it is there and when it works, you don’t notice it and don’t think about it, but when it is not enough and when malfunctions begin in its work, then the normal course of life is disrupted.

It is well known that in modern conditions the intellectual potential of the population - along with the demographic, territorial, raw materials, technological parameters of a particular society - is the most important basis for its progressive development.

Firstly, one of the decisive factors of economic development is now intellectual production, and the key form of property is intellectual property. According to a number of analysts, at present we can talk about a global intellectual redivision of the world, which means fierce competition between individual states for the predominant possession of intellectually gifted people - potential carriers of new knowledge. Secondly, intellectual creativity, being an integral aspect of human spirituality, acts as a social mechanism that resists regressive lines in the development of society.

Glossary

Adaptation - A change in a system of relationships socially or culturally, that is, any structural or behavioral change that is of vital importance.

Assimilation - A mechanism in which a new object or new situation is integrated with a set of objects or another situation for which a schema already exists (according to Piaget)

Intelligence - General cognitive ability that determines a person’s readiness to assimilate and use knowledge and experience, as well as to behave intelligently in problem situations. In the broad sense of the word, it is the totality of all cognitive functions of an individual (sensation, perceptions, thinking, imagination). In the narrow sense of the word, this is only thinking. Identified with the system of mental operations, the effectiveness of an individual approach to the situation, with biopsychic adaptation to the current circumstances of life.

Abstract intelligence - Intelligence, the activity of which involves cognitive skills necessary for judgment and for operating with concepts

Concrete Intelligence - Practical intelligence responsible for solving everyday problems using knowledge and skills stored in memory

Plastic intelligence (according to Cattell) - Innate intelligence that underlies our ability to think, reason and abstract; By the age of 20, it reaches its maximum development, and then gradually worsens.

Formed intelligence (according to Cattell) - Intelligence developing on the basis of plastic intelligence, learning and experience; it continues to form throughout life.

Cognitive - Relating to cognition, thinking.

Intelligence Quotient (IQ) - The ratio of mental age to chronological age (in months), multiplied by 100. By definition, a normal (average) IQ is 100 points, since in this case mental age corresponds to chronological age.

Chronological age - Age calculated based on a person's date of birth

List of sources used

Eysenck G.Yu. Test your abilities. - St. Petersburg, 1994

Bloom F. et al. Brain, mind and behavior. - M., 1988

Druzhinin V.N. Psychology of general abilities. St. Petersburg: Peter, - 2008. - 362 p.

History of philosophy in brief / Transl. from Czech I.I. Boguta. M.: Mysl, 1991. - 590 p.

History of Philosophy: Encyclopedia. - Mn.: Interpressservice; Book House. 2002. - 1376 p.

Kholodnaya M.A. Psychology of intelligence: paradoxes of research. M., - 2001. - 272 p.

Piaget J. Speech and thinking of a child. - M., 1997

Psychology. Dictionary. - M., 1990

Solso R.L. Multivariate analysis of intellectual abilities - pros and cons.

Hubel D. Eye, brain, vision. - M., 1990

Posted on Allbest.ru

Similar documents

Studying the types of cognitive functions of an individual: logical, intuitive and abstract intelligence. Analysis of the theory of primary abilities and the tripartite theory of intelligence. Descriptions of tests for differentiating individuals according to their level of intellectual development.

abstract, added 05/02/2011

Verbal and nonverbal intelligence tests. Features of measuring the intellectual development of individuals using the D. Wechsler scale. Basic approaches to understanding the essence of intelligence. Ideas about its structure. Methods for measuring intelligence in the twentieth century.

lecture, added 01/09/2012

Intelligence as an individual property of a person. General scientific approaches to the study of intelligence. Features of social intelligence and psychological qualities of the individual, its relationship with general intelligence and its components. Hierarchical models of intelligence.

test, added 02/11/2013

Psychometric, cognitive, multiple theories of intelligence. Study of the theories of M. Kholodnaya. Gestalt-psychological, ethological, operational, structural-level theory of intelligence. Theory of functional organization of cognitive processes.

test, added 04/22/2011

The concept of human emotional intelligence in psychology. Basic models of emotional intelligence. Theories of emotional intelligence in foreign and domestic psychology. Victimization as a teenager’s predisposition to produce victim behavior.

course work, added 07/10/2015

The history of the formation of the concept of emotional intelligence in foreign and domestic psychology, its main features and components. Study of manifestations of emotional intelligence and methods for its diagnosis, based on the proposed models.

course work, added 12/15/2013

Mental activity and development of intelligence. Structure of intelligence. Explanatory approaches in experimental psychological theories of intelligence. Intellectual abilities. Intelligence and biological adaptation of children. Oligophrenia and its influence.

thesis, added 01/25/2009

Definition, structure, theories of intelligence. Intellectual potential of the individual. Intelligence assessment. Theoretical and practical significance of knowledge about the nature of human intellectual abilities. A structural approach to intelligence as a category of consciousness.

test, added 10/25/2010

The concept of emotional intelligence and the main approaches to its study in modern psychology. Self-awareness, self-control and relationship management. Four methods for diagnosing emotional intelligence and its connection with adaptation. Questionnaire "EmIn" D.V. Lucina.

course work, added 03/18/2013

Characteristics, similarities and differences of the main theories of intelligence. Features and essence of theories of intelligence in the study of M.A. Cold. The concept of operational and structural-level theories and the theory of functional organization of cognitive processes.

In general intelligence- this is a system of mental mechanisms that determine the possibility of constructing a subjective picture of what is happening “inside” the individual.

From a psychological point of view, the purpose of intelligence is to create order out of chaos based on bringing individual needs into line with the objective requirements of reality.

All those areas of human activity where it is necessary to learn something, do something new, make a decision, understand, explain, discover - all this is the sphere of action of the intellect.

The main theories of intelligence include:

Psychometric theories of intelligence

These theories claim that individual differences in human cognition and mental abilities can be adequately measured by special tests. Adherents of psychometric theory believe that people are born with different intellectual potential, just as they are born with different physical characteristics, such as height and eye color. They also argue that no amount of social programs can transform people with different mental abilities into intellectually equal individuals.

Psychometric theories of intelligence:

- Ch. Spearman's two-factor theory of intelligence.

- Theory of primary mental abilities.

- Cubic model of the structure of intelligence.

Ch. Spearman's two-factor theory of intelligence. Charles Spearman, an English statistician and psychologist, creator of factor analysis, he drew attention to the fact that there are correlations between different intelligence tests: those who perform well on some tests turn out, on average, to be quite successful on others. The structure of intellectual properties proposed by Charles Spearman turns out to be extremely simple and is described by two types of factors - general and specific. These two types of factors gave the name to Charles Spearman's theory - the two-factor theory of intelligence.

The main postulate of Charles Spearman's theory remained unchanged: individual differences between people in intellectual characteristics are determined primarily by general abilities.

Theory of primary mental abilities. In 1938, Lewis Thurston's work “Primary Mental Abilities” was published, in which the author presented a factorization of 56 psychological tests diagnosing various intellectual characteristics. The structure of intelligence according to L. Thurston is a set of mutually independent and adjacent intellectual characteristics, and in order to judge individual differences in intelligence, it is necessary to have data on all these characteristics.

In the works of L. Thurston's followers, the number of factors obtained by factorizing intellectual tests (and, consequently, the number of intellectual characteristics that must be determined when analyzing the intellectual sphere) was increased to 19. But, as it turned out, this was far from the limit.