Petrovsky Yaroshevsky psychology download doc. A.v. Petrovsky, M. G. Yaroshevsky. foundations of theoretical psychology. History and theory of psychology

M.: Academy, 1996 - 496 p.

The book is based on the textbook “General Psychology,” which was reprinted many times from 1970 to 1986 and translated into German, Finnish, Danish, Chinese, Spanish and many other languages. The textbook has been radically revised and supplemented with new materials that meet the modern level of development of psychological science.

Despite all the content and completeness, the textbook retains the features of propaedeutics in relation to subsequent basic and practice-oriented academic disciplines. In fact, each chapter of this book is the basis of a corresponding textbook for a specific psychological discipline. For example, the chapters “Communication” and “Personality” are a kind of preamble for the course (program and textbook) “Social Psychology”. Chapters devoted to cognitive processes: “Memory”, “Perception”, “Thinking”, “Imagination” are introduced into the course “Educational Psychology” or “Psychology of Learning”.

Format: pdf/zip

Size: 2.7 2 MB

/Download file

![]()

Format: doc/zip

Size: 733 KB

/Download file

CONTENT

Part I. SUBJECT AND HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY

Chapter 1. Historical path of development of psychology (M.G, Yaroshevsky).................. S

1. Ancient psychology.................................................. ........................... 6

2. Psychological thought of the New Age.................................................... 18

3. The origins of psychology as a science................................................... ......... 28

4. Development of experimental and differential psychology.... 38

5. Main psychological schools.................................................... ....... 44

6. Evolution of schools and directions................................................. ............. 57

Chapter 2. Modern psychology. Its subject and place in the system of sciences (A.V. Petrovsky). 70

1. Subject of psychology......................................................... ........................... 70

2. Psychology and natural science.................................................. ................ 73

3. Psychology and scientific and technological progress.................................................... 76

4. Psychology and pedagogy................................................... ........................ 77

5. The place of psychology in the system of sciences.................................................... .......... 80

6. Structure of modern psychology.................................................. ...... 80

7. The concept of general psychology................................................... ................ 85

Chapter 3. Methods of psychology (LA. Karpenko)............................................ ............... 88

1. Subjective method.................................................... ........................... 88

2. Objective method.................................................... ........................... 91

3. Objective research methods................................................................. ...... 92

4. Experimental method......................................................... ........................... 96

5. Measurements in psychology.................................................... ........................ 100

6. Survey method......................................................... ........................................... 106

7. Projective methods.................................................. ........................... 111

8. Method of reflected subjectivity.................................................... .......... 112

9. Organization of a specific psychological study............ 113

Part II. PSYCHOLOGICAL PROCESSES AND STATES

Chapter 4. Sensations (T.P. Zinchenko)..................................................... ........................... 117

1. The concept of sensation.................................................... ................................... 117

2. General patterns of sensations.................................................... ........ 126

Chapter 5. Perception (V.L. Zinchenko, T.P. Zinchenko).................................. .......... 137

1. Characteristics of perception and its features.................................... 137

2. Perception as action................................................... ........................ 146

3. Perception of space................................................... ........................... 149

4. Perception of time and motion................................................. .......... 159

Chapter 6. Memory (G.K. Sereda).................................................... ........................................ 164

1. General concept of memory................................................... ........................... 164

2. Types of memory........................................................ ........................................... 172

3. General characteristics of memory processes.................................................... 177

4. Memorization................................................... ........................................... 179

5. Playback................................................... ................................... 187

6. Forgetting and storing.................................................... ........................... 190

7. Individual differences in memory.................................................... ........ 194

Chapter 7. Thinking (A.V. Brushlinsky).................................................... ........................ 196

1. General characteristics of thinking................................................... ......... 196

2- Thinking and problem solving.................................................... .................... 209

3. Types of thinking............................................................. .................................... 217

Chapter 8. Imagination (A.V. Petrovsky).................................................... .................... 222

1. The concept of imagination, its main types and processes.................... 222

2. Physiological foundations of imagination processes.................................... 230

3. The role of fantasy in children’s play and adults’ creativity.................................. 233

Chapter 9. Feelings (AL Petrovsky)................................................... ............................ 239

1. Definition of feelings and their physiological basis.................................... 239

2. Forms of experiencing feelings................................................... ................... 243

3. Feelings and personality................................................. ................................... 252

Part III. INTERDISCIPLINARY CONCEPTS OF PSYCHOLOGY

Chapter 10. Activity (L.I. Petrovsky, V.L. Petrovsky).................................259

1. Internal organization of human activity.................................................259

2. External organization of activity................................................... .......267

3. Painful actions.................................................. ................................276

Chapter 11. Communication (L.V. Petrovsky).................................................... ........................280

1. The concept of communication.................................................... ...............................280

2. Communication as the exchange of information................................................... .........283

3. Communication as interpersonal interaction.................................................292

4. Communication as people’s understanding of each other.................................................. 301

Chapter 12. Groups (L.V. Petrovsky).................................................... ...............................310

1. Groups and their classification................................................... ...............310

2. The highest form of group development.................................................. ............312

3. Differentiation between groups of different levels of development...................................320

4. Integration of groups of different levels of development....................................331

5. Student groups: psychological features of the work of a teacher (MAO. Kondraty:i).337

6. Structure of relationships in the family.................................................. .....350

Chapter 13. Consciousness (B.S. Mukhina, L.V. PstroiskiP)................................................. ....362

1. Development of the psyche in phylogenesis.................................................... .............362

2. The emergence of consciousness.................................................... ...........................366

3. The structure of consciousness and the unconscious in the human psyche........................372

Chapter 14. Personality (L.V. Petrovsky).................................................... ...........................385

1. The concept of personality in psychology.................................................... .........385

2. Personality structure.................................................... ...............................390

3. Basic theories of personality in foreign psychology...................................397

4. Personality orientation............................................................. .................... 401

5. Personal self-awareness................................................................. ........................ 407

6. Personal development.................................................. ................................... 417

Part IV. INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERISTICS OF A PERSON

Chapter 15. Temperament (N.S. Leites)................................................. ............................... 432

1. General concept of temperament.................................................... ............... 432

2. The role of temperament in work and educational activities.....,............ 442

3. Temperament and parenting problems.................................................. ... 447

Chapter 16. Character (A.V. Petrovsky)................................................. ........................... 451

1. The concept of character................................................... ................................ 451

2. Character structure.................................................... ........................... 452

3. Nature and manifestations of character................................................. .......... 458

Chapter 17. Abilities (A.V. Petrovsky^...................................... .................... 468

1. The concept of abilities................................................... ........................... 468

2. Structure of abilities.................................................... ........................... 474

3. Talent, its origin and structure.................................................... .. 476

4. Natural prerequisites for abilities and talent.................................... 480

5. Formation of abilities................................................... ................ 486

Application. Glossary of terms................................................... ........................... 489

Recommended reading................................................... ............... 491

n1.doc

Petrovsky A.V., Yaroshevsky M.G.

HISTORY AND THEORY OF PSYCHOLOGY

Volume 2

Publishing house "Phoenix"

Rostov-on-Don

Artist O. Babkin

Petrovsky A.V., Yaroshevsky M.G.

And 84 History and theory of psychology. Rostov-on-Don:

Publishing house "Phoenix", 1996. Volume 2. - 416 p.

AND 4704010000 _ without announcement BBK 65.5

Petrovsky A.V.

ISBN 5-85880-159-5 Yaroshevsky M.G.,

© Phoenix, 1996.

PART FOUR

PSYCHOPHYSICAL AND

PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGICAL

PROBLEMS

Chapter 10

PSYCHOPHYSICAL PROBLEM

Monism, dualism and pluralism

In countless attempts to determine the nature of mental phenomena, an understanding of its relationships with other phenomena of existence has always been assumed, in an explicit or implicit form.

The question of the place of the psyche in the material world was variously resolved by adherents of the philosophy of monism (the unity of the world order), dualism (coming from two fundamentally different principles) and pluralism (believing that there are many such principles).

Accordingly, we are already familiar with the first natural scientific views on the soul (psyche) as one of the particular transformations of a single natural element. These were the first views of the ancient Greek philosophers, who represented this element in the form of air, fire, and a flow of atoms.

Also, attempts arose to consider the units of the world not to be material, sensually visible elements, but numbers, the relationships of which form the harmony of the cosmos. This was the teaching of Pythagoras (VI century BC). It should be taken into account that a single substance, which serves as the basis of all things (including the soul), was thought of as living, animate (see above - hylozoism), and for Pythagoras and his school number was not at all an extra-sensory abstraction. The cosmos he formed was seen as a geometric-acoustic unity. For the Pythagoreans, the harmony of the spheres meant their sound.

All this indicates that the monism of the ancients had a sensual coloring and sensual tonality. It was in a sensual, and not an abstract, image that the idea of the inseparability of the mental and physical was affirmed.

As for dualism, it received its most dramatic, classical expression from Plato. In his polemical dialogues, he expanded everything that was possible: the ideal and the material, the felt and the conceivable, the body and the soul. But the historical meaning of Plato’s teaching, its influence on the philosophical and psychological science of the West, right up to the modern era, does not lie in the opposition of the sensory world to the visible, the senses to the mind. Plato discovered the problem of the ideal. It was proven that the mind has very special, specific objects. Mental activity lies in joining them.

Because of this, the mental, having acquired the sign of ideality, turned out to be sharply separated from the material. Prerequisites arose for the opposition of ideal images of things to the things themselves, of spirit and matter. Plato exaggerated one of the features of human consciousness. But only then did she become noticeable.

Finally, something should be said about pluralism.

Just as monistic and dualistic ways of understanding the relationship of the psyche to the external material world had already developed in ancient times, the idea of pluralism arose. The term itself appeared much later. It was proposed in the 18th century by the philosopher X. Wolf (teacher of M.V. Lomonosov) to contrast monism. But already the ancient Greeks were looking for several “roots” of being instead of one. In particular, four elements were distinguished: earth, air, fire, water.

In modern times, in the teachings of personalism, which accepts each person as the only one in the Universe (W. James and others), the ideas of pluralism have become dominant. They split existence into many worlds and, in essence, remove from the agenda the question of the relationship between mental and extra-psychic (material) phenomena. Consciousness thereby turns into an isolated “island of the spirit.”

The real value of the psyche in a single chain of being is not only the subject of philosophical discussions. The relationship between what is given to consciousness in the form of images (or experiences) and what happens in the external physical world is inevitably presented in the practice of scientific research.

Soul as a way of assimilation

The first experience of a monistic understanding of the relationship of mental phenomena to the external world belongs to Aristotle. For previous teachings, there was no psychophysical problem here at all (since the soul was represented either as consisting of the same physical components as the surrounding world, or it, as was the case in Plato’s school, was opposed to it as a heterogeneous principle).

Aristotle, asserting the inseparability of soul and body, understood the latter as a biological body, from which all other natural bodies are qualitatively different. Nevertheless, it depends on them and interacts with them both at the ontological level (since life activity is impossible without the assimilation of matter) and at the epistemological level (since the soul carries knowledge about the external objects surrounding it).

The solution found by Aristotle in his quest to end Plato's dualism was truly innovative. It was based on a biological approach. Let us recall that Aristotle thought of the soul not as a single entity, but as formed by a hierarchy of functions: plant, animal (in today’s language, sensorimotor) and rational. The basis for explaining higher functions was the most elementary one, namely plant ones. He considered it in the fairly obvious context of the interaction of the organism with the environment.

Without the physical environment and its substances, the work of the “plant soul” is impossible. It absorbs external elements during nutrition (metabolism). However, an external physical process in itself cannot be the cause of the activity of this plant (vegetative) soul if the structure of the organism, which perceives the physical impact, were not disposed to this. Previous researchers considered fire to be the cause of life. But it is capable of growing and expanding. As for organized bodies, for their size and growth “there is a limit and a law.” Nutrition occurs due to external matter, but it is absorbed by a living body differently from an inorganic one, namely due to the “mechanics” of expedient distribution.

In other words, the soul is a way of assimilating the external and becoming familiar with it, specific to a living organization.

Aristotle applied the same model for solving the question of the relationship between the physical environment and an organism with a soul to explain the ability to sense. Here, too, an external physical object is assimilated by the organism according to the organization of the living body. A physical object is outside of it, but thanks to the activity of the soul it enters the body, imprinting in a special way not its substance, but its form. Which is what sensation is.

The main difficulties that Aristotle encountered while following this strategy arose during the transition from the sensorimotor (animal) soul to the rational one. Her work had to be explained by the same factors that would allow her to apply techniques to innovatively deal with the mysteries of nutrition and sensation.

Two factors were implied - an object external to the soul and a bodily organization adequate to it. However, objects “assimilated” by the rational part of the soul are characterized by a special nature. Unlike objects that act on the senses, they are devoid of substance. These are general concepts, categories, mental constructs. If the corporeality of the sense organ is self-evident, then nothing is known about the corporeal organ of knowledge of extrasensory ideas.

Aristotle sought to understand the activity of the rational soul not as a unique, incomparable phenomenon, but as akin to the general activity of the living, its special case. He believed that the principle of the transition of possibility into reality, that is, the activation of the internal potencies of the soul, has the same force both for the mind, which comprehends the general forms of things, and for the metabolism in plants or the sensation of the physical properties of an object by the sense organ.

But the absence of material objects adequate to the activity of the mind prompted him to admit the existence of ideas (general concepts) similar to those spoken about by his teacher Plato. Thus, he, following Plato, moving to the position of dualism, cut short the deterministic solution to the psychophysical problem at the level of the animal soul with its ability to possess sensory images.

Beyond this ability, the internal connections of mental functions with the physical world were severed.

Transformation of Aristotle's teachings into Thomism

Aristotle's doctrine of the soul solved biological and natural science problems. In the Middle Ages, it was rewritten into another language that suited the interests of Catholicism and was consonant with this religion.

The most popular copyist was Thomas Aquinas, whose books were canonized by the church under the name of Thomism. A typical feature of medieval ideology, reflecting the social structure of feudal society, was hierarchism: the younger exists for the benefit of the elder, the lower - for the sake of the higher, and only in this sense is the world expedient. Thomas extended the hierarchical template to the description of mental life, the various forms of which were placed in a stepped series - he is lower to higher. Every phenomenon has its place.

The souls are located in a stepped row - plant, animal, rational (human). Within the soul itself, abilities and their products (sensation, idea, concept) are hierarchically located.

The idea of “gradation” of forms meant for Aristotle the principle of development and originality of the structure of living bodies, which differ in levels of organization. In Thomism, the parts of the soul acted as its immanent forces, the order of which was determined not by natural laws, but by the degree of closeness to the Almighty. The lower part of the soul is turned to the mortal world and gives imperfect knowledge, the higher provides communication with the Lord and, by his grace, allows us to comprehend the order of phenomena.

In Aristotle, as we noted, the actualization of ability (activity) presupposes an object corresponding to it. In the case of a plant soul, this object is an assimilated substance; in the case of an animal soul, it is a sensation (as the form of an object affecting the sense organ); in the case of a rational soul, it is a concept (as an intellectual form).

This Aristotelian position is transformed by Thomas into the doctrine of intentional acts of the soul. In intention as an internal, mental action, content always “coexists” - the object to which it is directed. (The object was understood as a sensory or mental image.)

There was a rational aspect to the concept of intention. Consciousness is not a “stage” or “space” filled with “elements.” It is active and initially objective. Therefore, the concept of intention did not disappear along with Thomism, but moved into the new empirical psychology when the functional direction opposed Wundt’s school.

An important role in strengthening the concept of intention was played by the Austrian philosopher F. Brentano, who at the end of the 19th century came up with his own plan, different from Wundt’s, for transforming psychology into an independent science, the subject of which is not studied by any other science (see above).

As a Catholic priest, Brentano studied the psychological works of Aristotle and Thomas. However, Aristotle considered the soul to be a form of the body - and in relation to its plant and sensory functions - associated with the physical world (bodies of external nature). The intention of consciousness and the object that coexists with it have acquired the character of spiritual entities. Thus, the psychophysical problem was “closed.”

Turning to Optics

The psychophysical problem acquired new content in the context of the successes of natural science in the field of optics, which combined experiment with mathematics. This branch of physics was successfully developed in the Middle Ages by both Arabic-speaking and Latin-speaking researchers. Within the boundaries of the religious worldview, they, having made the mental phenomenon (visual image) dependent on the laws objectively operating in the external world, returned to the psychophysical problem removed from the agenda by Thomism.

Along with the works of Ibn al-Haytham, the doctrine of “perspective” of Roger Bacon (c. 1214 - 1294) played an important role in strengthening this trend.

Optics switched thought from a biological orientation to a physical and mathematical one. The use of diagrams and concepts of optics to explain how an image is constructed in the eye (that is, a mental phenomenon arising in a bodily organ) made physiological and mental facts dependent on the general laws of the physical world. These laws - in contrast to the Neoplatonic speculation about the heavenly light, the radiation (emanation) of which the human soul was considered to be - were empirically tested (in particular through the use of various lenses) and received mathematical expression.

The interpretation of a living body (at least one of its organs) as a medium where physical and mathematical laws operate was a fundamentally new line of thought, which ancient science did not know. Regardless of the degree and nature of the awareness of its novelty and importance by the medieval naturalists themselves, an irreversible change occurred in the structure of scientific and psychological thinking, the starting point of which was the understanding of the sensory act (visual sensation) as a physical effect, built according to the laws of optics. Although only a certain range of phenomena related to the function of one of the organs was meant, an intellectual revolution objectively began, which subsequently captured the entire sphere of mental activity, up to and including its highest manifestations.

Of course, finding out the paths of movement of light rays in the eye, the features of binocular vision, etc. is very important in order to explain the mechanism of the appearance of a visual image. But what are the grounds for seeing this as something more than elucidating the physical prerequisites for one of the varieties of reception?

Whether Ibn al-Haytham, Roger Bacon, and others claimed more, or whether their intention was a general reconstruction of the original principles for the explanation of mental processes, they laid the foundation for such a reconstruction. Relying on optics, they overcame the teleological method of explanation. The movement of a light beam in a physical environment depends on the properties of this environment, and is not directed in advance by a given goal, as was assumed in relation to movements occurring in the body.

The work of the eye was considered a model of expediency. Let us remember that Aristotle saw in this work a typical expression of the essence of the living body as matter organized and controlled by the soul: “If the eye were a deceitful creature, its soul would be sight”. Vision, which became dependent on the laws of optics, ceased to be the “soul of the eye” (in the Aristotelian interpretation). It was included in a new causal series and was subject to physical rather than immanent-biological necessity.

Mathematical structures and algorithms have long been used as an expression of the principle of necessity 1 .

But in themselves they are insufficient for a deterministic explanation of nature, as evidenced by the history of the Pythagoreans and Neo-Pythagoreans, Platonists and Neoplatonists, schools in which the deification of number and geometric form coexisted with outright mysticism. The picture changed radically when mathematical necessity became an expression of the natural course of things in the physical world, accessible to observation, measurement, and empirical study, both direct and using additional means (which took on the meaning of experimental instruments - for example, optical glasses).

Optics was the area where mathematics and experience were combined. The combination of mathematics and experiment, leading to major achievements in the knowledge of the physical world, at the same time transformed the structure of thinking. The new way of thinking in natural science changed the nature of the interpretation of mental phenomena. It was initially established on a small “patch”, which was the area of visual sensations.

But, once established, this method, as more perfect, more adequate to the nature of phenomena, could no longer disappear.

Mechanics and changing concepts of soul and body

The image of nature as a grandiose mechanism that arose in the era of the scientific revolution of the 17th century and the transformation of the concept of the soul (which was considered the driving principle of life) into the concept of consciousness as the subject’s direct knowledge of his thoughts, desires, etc. decisively changed the general interpretation of the psychophysical problem.

It is necessary to emphasize here that the thinkers of this period really considered the problem in question as a relationship between mental and physical processes in order to explain the place of the psyche (consciousness, thinking) in the universe, in nature as a whole. Only one thinker, namely Descartes, did not limit himself to analyzing the relationships between consciousness and physical nature, but tried to combine a psychophysical problem with a psychophysiological one, with an explanation of the changes that physical processes undergo in the body, subject to the laws of mechanics, giving rise to “passions of the soul.”

However, for this, Descartes had to leave the realm of purely physical phenomena and project the image of a machine (i.e., a device where the laws of mechanics operate in accordance with a design created by man).

Other major thinkers of the era presented the relationship between the bodily and the spiritual (mental) on a “cosmic scale”, without offering productive ideas about the unique characteristics of the living body (as a device producing the psyche) in contrast to the inorganic one. Therefore, in their teachings, the psychophysical problem was not distinguished from the psychophysiological one.

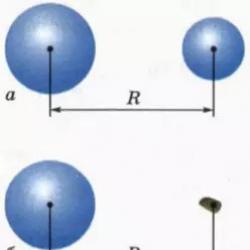

Psychophysical interaction hypothesis

Having attributed the soul and body to fundamentally different areas of existence, Descartes tried to explain their empirically obvious connection through the interaction hypothesis. To explain the possibility of interaction between these two substances, Descartes suggested that the body has an organ that ensures this interaction, namely the so-called pineal gland (epiphysis), which serves as an intermediary between the body and consciousness (see above). This gland, according to Descartes, perceiving the movement of “animal spirits”, in turn is capable, thanks to vibration (caused by the action of the soul), of influencing their purely mechanical flow. Descartes admitted that, without creating new movements, the soul can change their direction, just as a rider is able to change the behavior of the horse he controls. After Leibniz established that in all bodies in dynamic interaction, not only the quantity (force), but also the direction of movement remains unchanged, Descartes’ argument about the ability of the soul to spontaneously change the direction of movement turned out to be incompatible with physical knowledge.

The reality of interaction between soul and body was rejected by Spinoza, occasionalists, and Leibniz, who were brought up on Cartesian teaching. Spinoza comes to materialist monism. Leibniz - to idealistic pluralism.

Innovative version of Spinoza

Recognizing the attributive (and not substantial) difference between thinking and extension and, at the same time, their inseparability, Spinoza postulated: “Neither the body can determine the soul to thinking, nor the soul can determine the body either to movement, or to rest, or to anything else (if there is anything else?)” 2 .

The belief that the body moves or is at rest under the influence of the soul arose, according to Spinoza, due to ignorance of what it is capable of as such, by virtue of the laws of nature alone, considered exclusively as corporeal. This revealed one of the epistemological sources of belief in the ability of the soul to arbitrarily control the behavior of the body, namely, ignorance of the true capabilities of the bodily structure in itself.

"When people say, Spinoza continues, that this or that action of the body originates from the soul, which has power over the body, they do not know what they are saying, and only in beautiful words they admit that the true reason for this action is unknown to them and they are not at all surprised by it.” 3 .

This attack on “fine words” replacing the study of real causes was of historical significance. She directed the search for the actual determinants of human behavior, the place of which in traditional explanations was occupied by the soul (consciousness, thought) as the primary source.

Emphasizing the role of causal factors inherent in the activity of the body in itself, Spinoza at the same time rejected that view of the determination of mental processes, which later received the name epiphenomenalism, the doctrine that mental phenomena are ghostly reflections of bodily ones. After all, the mental as thinking is, according to Spinoza, the same attribute of material substance as its extension. Therefore, considering that the soul does not determine the body to think, Spinoza also argued that the body cannot determine the soul to think.

What motivated this conclusion? According to Spinoza, it follows from the theorem: “Every attribute of one substance must be represented through itself” 4 .

And what is true in relation to attributes is also true in relation to modes, i.e. the entire diversity of the individual, which corresponds to one or another attribute: the modes of one do not contain the modes of another.

The soul as a thinking thing and the body as the same thing, but considered in the attribute of extension, cannot determine each other (interact) not because of their separate existence, but because of their inclusion in the same order of nature.

Both soul and body are determined by the same reasons. How can they exert a causal influence on each other?

The question of Spinozist interpretation of the psychophysical problem requires special analysis. Erroneous, in our opinion, is the view of those historians who, rightly rejecting the version of Spinoza as a supporter (and even the founder) of psychophysical parallelism, present him as a supporter of psychophysical interaction.

In fact, Spinoza put forward an extremely deep idea, which remained largely ununderstood not only by him, but also by our contemporaries, that there is only one “causal chain”, one pattern and necessity, one and the same “order” for things (including such thing, like a body), and for ideas. Difficulties arise when the Spinozist interpretation of the psychophysical problem (the question of the relationship between the mental and nature, the physical world as a whole) is translated into the language of a psychophysiological problem (the question of the relationship between mental processes and physiological, nervous ones). It is then that the search for correlations between the individual soul and the individual body begins, outside the general, universal pattern, to which both are inevitably subordinated, included in the same causal chain.

The famous 7th theorem of the 2nd part of “Ethics” “The order and connection of ideas are the same as the order and connection of things” meant that the connections in thinking and space are identical in their objective causal basis. Accordingly, in the scholium to this theorem, Spinoza states: “Whether we represent nature under the attribute of space, or under the attribute of thinking, or under any other attribute, in all cases we will find the same order, in other words, the same connection of causes, i.e. the same things follow each other" 5 .

Psychophysical parallelism

The occasionalist Melebranche (1638 - 1715), a follower of Descartes, adhered to a philosophical orientation opposite to the Spinozist one. He taught that the correspondence between the physical and mental, ascertained by experience, is created by divine power. The soul and body are completely independent entities from each other, so their interaction is impossible. When a certain state arises in one of them, the deity produces a corresponding state in the other.

Occasionalism (and not Spinoza) was the true founder of psychophysical parallelism. It is this concept that Leibniz accepts and further develops, who, however, rejected the assumption of the continuous participation of the deity in every psychophysical act. Divine wisdom manifested itself, in his opinion, in pre-established harmony. Both entities - soul and body - carry out their operations independently and automatically due to their internal structure, but since they are put into action with the greatest precision, one gets the impression of dependence of one on the other. The doctrine of pre-established harmony made the study of the bodily determination of the psyche meaningless. It simply denied it. "There is no proportionality, Leibniz stated categorically, between an incorporeal substance and one or another modification of matter" 6 .

The nihilistic attitude towards the view of the body as a substrate of mental manifestations had a heavy impact on the concepts of German psychologists who trace their ancestry to Leibniz (Herbart, Wundt and others).

Hartley: the single beginning of the physical,

physiological and mental

The psychophysical problem became psychophysiological in the 18th century with Hartley (in the materialistic version) and in H. Wolf (in the idealistic version). The dependence of the psyche on the universal forces and laws of nature was replaced by its dependence on processes in the body, in the nervous substrate.

Both philosophers approved the so-called psychophysiological parallelism. But the difference in their approaches concerned not only a general philosophical orientation.

Hartley, despite the fantastic nature of his views on the substrate of mental phenomena (as mentioned above, he described nervous processes in terms of vibrations), tried to bring the physical, physiological and mental under a common denominator. He emphasized that he came to his understanding of man under the influence of Newton’s works “Optics” and “Principles” (“Mathematical principles of natural philosophy”).

The important role of the study of light rays has already been noted in repeated attempts to explain various subjective phenomena by the physical laws of their propagation and refraction. Hartley's advantage over his predecessors is that he chose a single principle, gleaned from exact science, to explain processes in the physical world (oscillations of the ether) as a source of processes in the nervous system, parallel to which there are changes in the mental sphere (in the form of associations along adjacency).

If Newton’s physics remained unshakable until the end of the 19th century, then Hartley’s “vibratory physiology”, on which he relied in his doctrine of associations, was fantastic, having no basis in real knowledge about the nervous system. Therefore, one of his faithful followers, D. Priestley, proposed to accept and further develop Hartley’s doctrine of associations, discarding the hypothesis of nervous vibrations. Thus, this teaching was deprived of bodily correlations, both physiological and mental.

Proponents of associative psychology (J. Mill and others) began to interpret consciousness as a “machine” operating according to its own autonomous laws.

Advances in physics and the doctrine of parallelism

The first half of the 19th century was marked by major advances in physics, among which the discovery of the law of conservation of energy and its transformation from one form to another stands out. The new, “energetic” picture of the world made it possible to deal a crushing blow to vitalism, which endowed the living body with a special vital force.

In physiology, a physicochemical school emerged, which determined the rapid progress of this science. The body (including the human) was interpreted as a physico-chemical, energy machine. He naturally fit into the new picture of the universe. However, the question of the place of the psyche and consciousness in this picture remained open.

For most researchers of psychic phenomena, psychophysical parallelism seemed an acceptable version.

The circulation of various forms of energy in nature and the body remained “on the other side” of consciousness, the phenomena of which were considered as irreducible to physicochemical molecular processes and irreducible from them. There are two series between which there is a parallelism relationship. To admit that mental processes can influence physical ones means to deviate from one of the fundamental laws of nature.

In this scientific and ideological atmosphere, supporters of subsuming mental processes under the laws of the movement of molecules, chemical reactions, etc. appeared. This approach (its supporters were called vulgar materialists) deprived the study of the psyche of claims to study reality that is important for life. It came to be called epiphenomenalism - the concept according to which the psyche is an “excess product” of the work of the “machine” of the brain (see above).

Meanwhile, events occurred in natural science that proved the meaninglessness of such a view (incompatible with everyday consciousness, which testifies to the real impact of mental phenomena on human behavior).

Biology adopted Darwin's doctrine of the origin of species, from which it was clear that natural selection mercilessly destroys “surplus products.” At the same time, the same teaching encouraged us to interpret the environment (nature) surrounding the organism in completely new terms - not physical and chemical, but biological, according to which the environment acts not in the form of molecules, but as a force that regulates the course of life processes, including mental.

The question of psychophysical correlations turned into a question of psychobiological ones.

Psychophysics

At the same time, in physiological laboratories, where the objects were the functions of the sense organs, the logic of the research itself encouraged us to recognize these functions as having an independent meaning, to see in them the action of special laws that did not coincide with physicochemical or biological ones.

The transition to experimental study of the sense organs was due to the discovery of differences between sensory and motor nerves. This discovery gave natural scientific strength to the idea that a subjective sensory image arises as a product of irritation of a certain nervous substrate. The substrate itself was thought of - in accordance with the achieved level of information about the nervous system - in morphological terms, and this, as we have seen, contributed to the emergence of physiological idealism, which denied the possibility of any other real, material basis for sensations other than the properties of nervous tissue. The dependence of sensations on external stimuli and their relationships has lost its decisive significance in this concept. Since, however, this dependence really exists, it inevitably had to come to the fore with the progress of experimental research.

Its natural character was one of the first to be discovered by the German physiologist and anatomist Weber (see above), who established that in this area of phenomena exact knowledge is achievable - not only deduced from experience and verified by it, but also allowing mathematical expression.

As already mentioned, at one time Herbart’s attempt to subsume the natural course of mental life under mathematical formulas failed. This attempt failed because of the fictitious nature of the calculation material itself, and not because of the weakness of the mathematical apparatus. Weber, who experimentally studied skin and muscle sensitivity, managed to discover a certain, mathematically formulated relationship between physical stimuli and sensory reactions.

Note that the principle of “specific energy” made no sense in any statement about the natural relations of sensations to external stimuli (since, according to this principle, these stimuli do not perform any function other than actualizing the sensory quality inherent in the nerve).

Weber, unlike I. Müller and other physiologists who attached primary importance to the dependence of sensations on neuroanatomical elements and their structural relationships, made the dependence of tactile and muscle sensations on external stimuli the object of research.

By checking how pressure sensations varied when the intensity of stimuli changed, he established a fundamental fact: differentiation does not depend on the absolute difference between values, but on the ratio of a given weight to the original one.

Weber applied a similar technique to sensations of other modalities - muscular (when weighing objects with the hand), visual (when determining the length of lines), etc. And everywhere a similar result was obtained, which led to the concept of a “barely noticeable difference” (between the previous and subsequent sensory effect) as a constant value for each modality. The "barely noticeable difference" in the increase (or decrease) of each kind of sensation is something constant. But in order for this difference to be felt, the increase in irritation must, in turn, reach a certain magnitude, the greater, the stronger the existing irritation to which it is added.

The significance of the established rule, which Fechner later called Weber's law (an additional stimulus must be in a constant relation to the given one for each modality in order for a barely noticeable difference in sensations to arise), was enormous. It not only showed the orderly nature of the dependence of sensations on external influences, but also contained (implicitly) a methodologically important conclusion for the future of psychology about the subordination of number and measure of the entire field of mental phenomena to their conditioning by physical ones.

Weber's first work on the natural relationship between the intensity of stimulation and the dynamics of sensations was published in 1834. But then she did not attract attention. And, of course, not because it was written in Latin. After all, Weber’s subsequent publications, in particular his excellent (already in German) review article for the four-volume “Physiological Dictionary” by Rud. Wagner, where previous experiments on determining thresholds were reproduced, also did not draw attention to the idea of a mathematical relationship between sensations and stimuli.

At that time, Weber's experiments were highly regarded by physiologists not because of the discovery of this relationship, but because of the establishment of an experimental approach to skin sensitivity, in particular, the study of its thresholds, which vary in value on different parts of the body surface. Weber explains this difference by the degree of saturation of the corresponding area with innervated fibers.

Weber's hypothesis about the “circles of sensations” (the surface of the body was represented as divided into circles, each of which was equipped with one nerve fiber; and it was assumed that the system of peripheral circles corresponded to their cerebral projection) 7 acquired exceptional popularity in those years. Is it because it was in tune with the then dominant “anatomical approach”?

Meanwhile, the new line in the study of the psyche outlined by Weber: the calculation of the quantitative relationship between sensory and physical phenomena remained inconspicuous until Fechner singled it out and turned it into the starting point of psychophysics.

The motives that led Fechner to a new field were significantly different from those of the natural-scientific materialist Weber. Fechner recalled that on a September morning in 1850, thinking about how to refute the materialistic worldview that prevailed among physiologists, he came to the conclusion that if the Universe - from planets to molecules - had two sides - the “light” or spiritual, and the “shadow” ”, or material, then there must be a functional relationship between them, expressible in mathematical equations. If Fechner had been only a religious man and a metaphysical dreamer, his plan would have remained in the collection of philosophical curiosities. But at one time he occupied the department of physics and studied the psychophysiology of vision. To substantiate his mystical-philosophical construction, he chose experimental and quantitative methods. Fechner's formulas could not help but make a deep impression on his contemporaries.

Fechner was inspired by philosophical motives: to prove, in contrast to the materialists, that mental phenomena are real and their real magnitudes can be determined with the same accuracy as the magnitudes of physical phenomena.

The methods of barely noticeable differences, average errors, and constant irritations developed by Fechner entered experimental psychology and at first determined one of its main directions. Fechner's Elements of Psychophysics, published in 1860, had a profound impact on all subsequent work in the field of measurement and calculation of mental phenomena - right up to the present day. After Fechner, the legitimacy and fruitfulness of using mathematical techniques for processing experimental data in psychology became obvious. Psychology began to speak in mathematical language - first about sensations, then about reaction time, associations and other factors of mental activity.

The general formula derived by Fechner, according to which the intensity of sensation is proportional to the logarithm of the intensity of the stimulus, became a model for the introduction of strict mathematical measures into psychology. Later it was discovered that this formula cannot claim universality. Experience has shown the limits of its applicability. It turned out, in particular, that its use is limited to stimuli of medium intensity and, moreover, it is not valid for all modalities of sensations.

Discussions flared up about the meaning of this formula, about its real foundations. Wundt gave it a purely psychological, and Ebbinghaus a purely physiological meaning. But regardless of possible interpretations, Fechner’s formula (and the experimental-mathematical approach to the phenomena of mental life it suggested) became one of the cornerstones of the new psychology.

The direction, the founder of which was Weber, and the theorist and renowned leader was Fechner, developed outside the general mainstream of the physiology of the sense organs, although at first glance it seemed to belong precisely to this branch of physiological science. This is explained by the fact that the patterns discovered by Weber and Fechner actually covered the relationship between mental and physical (and not physiological) phenomena. Although an attempt was made to derive these patterns from the properties of the neuro-brain apparatus, it was of a purely hypothetical, speculative nature and testified not so much to real, meaningful knowledge, but to the need for it.

Fechner himself divided psychophysics into external and internal, understanding the first as a natural correspondence between the physical and the mental, and the second as between the mental and the physiological. However, the secondary dependence (internal psychophysics) remained in the context of the interpretation of the law he established, beyond the limits of experimental and mathematical justification.

We see, therefore, that a unique direction in the study of the activity of the senses, known under the name of psychophysics and which became one of the foundations and components of psychology, which was emerging as an independent science, represented an area different from physiology. The object of study of psychophysics was the system of relations between psychological facts and external stimuli accessible to experimental control, variation, measurement and calculation. In this way, psychophysics was fundamentally different from the psychophysiology of the sense organs, although Weber obtained the original psychophysical formula by experimenting with cutaneous and muscle reception. In psychophysics, the activity of the nervous system was implied, but not studied. Knowledge about this activity was not part of the original concepts. Correlations of mental phenomena with external, physical, and not with internal, physiological agents turned out to be, given the then existing level of knowledge about the bodily substrate, the most accessible sphere of experimental development of facts and their mathematical generalization.

Psychophysical monism

Difficulties in understanding the relationship between physical nature and consciousness, a really urgent need to overcome dualism in the interpretation of these relationships, led at the turn of the 19th to 20th centuries to concepts whose motto was psychophysical monism.

The main idea was to imagine the things of nature and the phenomena of consciousness as “woven” from the same material. This idea was presented in various versions by Z. Mach, R. Avenarius, and W. James.

“Neutral” material for the distinction between physical and mental is, according to Mach, sensory experience, i.e. sensations. Considering them from one angle of view, we create a concept of the physical world (nature, matter), while from another angle of view they “turn into” phenomena of consciousness. It all depends on the context in which the same components of experience are included.

According to Avenarius, in a single experience there are different series. We take one series to be independent (for example, natural phenomena), while we consider the other to be dependent on the first (the phenomenon of consciousness).

By attributing a psyche to the brain, we commit an unacceptable “introjection,” namely, we put into the nerve cells something that is not there. It is absurd to look for images and thoughts in the skull. They are outside of it.

The prerequisite for such a view was the identification of the image of a thing with itself. If you do not distinguish them, then, indeed, it becomes mysterious how all the wealth of the knowable world can be contained in one and a half kilograms of brain mass.

In this concept, the psyche was disconnected from two most important realities, without correlation with which it becomes a mirage - both from the external world and from its bodily substrate. The futility of such a solution to the psychophysical (and psychophysiological) problem has been proven by the subsequent development of scientific thought.

Sechenov and Pavlov: physical stimulus as a signal

The transition from a physical interpretation of the relationship between an organism and the environment to a biological one gave rise to a new picture not only of the organism, the life of which (including its mental forms) was now thought of in its inseparable and selective connections with the environment, but also of the environment itself. The influence of the environment on a living body was not thought of as mechanical shocks or as a transition from one type of energy to another. The external stimulus acquired new essential characteristics, determined by the body's need to adapt to it.

This received its most typical expression in the emergence of the concept of stimulus-signal. Thus, the place of the previous physical and energy determinants was taken by signal ones. The pioneer of including the category of signal as its regulator in the general scheme of behavior was I.M. Sechenov (see above).

A physical stimulus, acting on the body, retains its external physical characteristics, but when it is received by a special bodily organ, it acquires a special form. In Sechenov's language - a form of feeling. This made it possible to interpret the signal as an intermediary between the environment and the organism orienting itself in it.

The interpretation of an external stimulus as a signal was further developed in the works of I.P. Pavlov on higher nervous activity. He introduced the concept of a signaling system, which allows the body to distinguish between environmental stimuli and, in response to them, acquire new forms of behavior.

The signaling system is not a purely physical (energy) quantity, but it cannot be attributed to the purely mental sphere, if we understand by it the phenomena of consciousness. At the same time, the signaling system has a mental correlate in the form of sensations and perceptions.

Vernadsky: the noosphere as a special shell of the planet

A new direction in understanding the relationship between the psyche and the outside world was outlined by V.I. Vernadsky.

Vernadsky's most important contribution to world science was his doctrine of the biosphere as a special shell of the Earth, in which the activity of living matter included in this shell is a geochemical factor on a planetary scale. Let us note that Vernadsky, having abandoned the term “life,” spoke specifically about living matter. By substance it was customary to understand atoms, molecules and what is built from them. But before Vernadsky, matter was thought of as abiotic or, if we accept his favorite term, as inert, devoid of characteristics that distinguish living beings.

Rejecting previous views on the relationship between the organism and the environment, Vernadsky wrote: “There is no inert, indifferent, unrelated environment for living matter, which was logically taken into account in all our ideas about the organism and the environment: the organism Wednesday; and there is no such opposition: the organism nature, in which what happens in nature may not be reflected in the body, is an inextricable whole: living matter= biosphere" 8 .

This equal sign was of fundamental importance. At one time I.M. Sechenov, having adopted the credo of advanced biology of the mid-19th century, rejected the false concept of the organism, which isolates it from the environment, whereas the concept of an organism should also include the environment that composes it. Defending in 1860 the principle of the unity of the living body and the environment, Sechenov followed the program of the physico-chemical school, which, having crushed vitalism, taught that forces act in a living body that do not exist in inorganic nature.

"We all children of the Sun", - said Helmholtz, emphasizing the dependence of any form of life on the source of its energy. Vernadsky, whose teaching represented a new round in the development of scientific thought, gave a different meaning to the principle of the unity of the organism and the environment. Vernadsky spoke not about a false understanding of the organism (like Helmholtz, Sechenov and others), but about a false understanding of the environment, thereby proving that the concept of the environment (biosphere) should also include the organisms that make it up. He wrote: “In the biogenic current of atoms and the energy associated with it, the planetary, cosmic significance of living matter is clearly manifested, for the biosphere is the only earthly shell into which cosmic energy, cosmic radiation and, above all, radiation from the Sun continuously penetrate.” 9 .

The biogenic flow of atoms to a large extent creates the biosphere, in which there is a continuous material and energy exchange between the inert natural bodies that form it and the living matter that populates it. Human activity generated by the brain as a transformed living substance dramatically increases the geological strength of the biosphere. Since this activity is regulated by thought, Vernadsky considered personal thought not only in its relation to the nervous substrate or the immediate external environment surrounding the organism (like naturalists of all previous centuries), but also as a planetary phenomenon. Paleontologically, with the advent of man, a new geological era begins. Vernadsky agrees (following some scientists) to call it psychozoic.

This was a fundamentally new, global approach to the human psyche, including it as a special force in the history of the globe, giving the history of our planet a completely new, special direction and rapid pace. In the development of the psyche, a factor was seen that limited the inert environment alien to living matter, exerting pressure on it, changing the distribution of chemical elements in it, etc. Just as the reproduction of organisms is manifested in the pressure of living matter in the biosphere, so the course of the geological manifestation of scientific thought puts pressure on the things it creates weapons against the inert, restraining environment of the biosphere, creating the noosphere, the kingdom of reason. It is obvious that for Vernadsky, the impact of thought, consciousness on the natural environment (outside of which this thought itself does not exist, because it, as a function of nervous tissue, is a component of the biosphere) cannot be other than mediated by tools created by culture, including means of communication.

The term “noosphere” (from the Greek “nous” - mind and “sphere” - ball) was introduced into the scientific language by the French mathematician and philosopher E. Leroy, who, together with another thinker Teilhard de Chardin, distinguished three stages of evolution: the lithosphere, the biosphere and noosphere. Vernadsky (who called himself a realist) gave this concept a materialistic meaning. Not limiting himself to the position expressed long before him and Teilhard de Chardin about a special geological “era of man,” he filled the concept of “noosphere” with new content, which he drew from two sources: the natural sciences (geology, paleontology, etc.) and the history of scientific thought .

Comparing the sequence of geological layers from the Archeozoic and the morphological structures of the life forms corresponding to them, Vernadsky points to the process of improvement of nervous tissue, in particular the brain. “Without the formation of the human brain there would be no scientific thought in the biosphere, and without scientific thought there would be no geological effect biosphere restructuring humanity" 10 .

Reflecting on the conclusions of anatomists about the absence of significant differences between the brains of humans and monkeys, Vernadsky noted: “This can hardly be interpreted otherwise than by the insensitivity and incompleteness of the methodology. For there can be no doubt about the existence of a sharp difference in the manifestations in the biosphere of the human mind and the mind of apes, closely related to geological effect and brain structure. Apparently, in the development of the human mind we see manifestations not of the gross anatomical, revealed in geological duration by changes in the skull, but of a more subtle change in the brain... which is associated with social life in its historical duration.” 11 .

The transition of the biosphere to the noosphere, while remaining a natural process, at the same time, according to Vernadsky, acquired a special historical character, different from the geological history of the planet.

By the beginning of the 20th century, it became obvious that scientific work could change the face of the Earth on a scale similar to great tectonic shifts. Having experienced an unprecedented explosion of creativity, scientific thought has revealed itself as a force of a geological nature, prepared by billions of years of the history of life in the biosphere. Taking the form, in the words of Vernadsky, of “universality”, embracing the entire biosphere, scientific thought creates a new stage in the organization of the biosphere.

Scientific thought is initially historical. And its history, according to Vernadsky, is not external and adjacent to the history of the planet. This is a geological force that changes it in the strictest sense. As Vernadsky wrote, the biosphere, created over geological time and established in its equilibrium, begins to change more and more deeply under the influence of the scientific thought of mankind. The newly created geological factor - scientific thought - changes the phenomena of life, geological processes, and the energy of the planet.

In the history of scientific knowledge, Vernadsky was especially interested in the question of the subject as the driving force of scientific creativity, about the importance of the individual and the level of society (political life) for the development of science, about the very methods of discovering scientific truths (it is especially interesting, he believed, to study those individuals who made discoveries long before they were truly recognized by science). "I think, - wrote Vernadsky, - By studying discoveries for the field of science made independently by different people, under different circumstances, it is possible to penetrate deeper into the laws of the development of consciousness in the world.” 12 . The concept of personality and its consciousness was comprehended by the scientist through the prism of his general approach to the universe and the place that man occupies in it. Reflecting on the development of consciousness and peace, in space, in the Universe, Vernadsky attributed this concept to the category of the same natural forces as life and all other forces acting on the planet. He hoped that by turning to historical relics in the form of those scientific discoveries that were made independently by different people in different historical conditions, it would be possible to verify whether the intimate and personal work of thought of specific individuals is carried out according to objective laws independent of this individual thought, which, like any laws of science, they are distinguished by repeatability and regularity.

The movement of scientific thought, according to Vernadsky, is subject to the same strict natural historical laws as the change of geological eras and the evolution of the animal world. The laws of the development of thought do not automatically determine the functioning of the brain as a living substance of the biosphere.

An organized corporation of scientists is not enough either. Special activity of the individual is required in the processes of transformation of the biosphere into the noosphere. It was this activity, the energy of the individual, that Vernadsky considered the most important factor in the transformative work taking place in the universe. He distinguished between unconscious forms of this work in the activities of successive generations and conscious forms, when from the centuries-old unconscious, collective and impersonal work of generations, adapted to the average level and understanding, “methods of discovering new scientific truths” are distinguished.

Vernadsky associated the acceleration of progress with the energy and activity of individuals who mastered these methods. With his “cosmic” way of understanding the universe, progress did not mean the development of knowledge in itself, but the development of the noosphere as a changed biosphere and thereby the entire planet as a systemic whole. Personal psychology turned out to be a kind of energetic principle, thanks to which the evolution of the Earth as a cosmic whole occurs.

The term “noosphere” meant a state of the biosphere - one of the shells of our planet - in which it acquires a new quality thanks to scientific work and the work organized through it. Upon closer examination, it becomes obvious that this sphere, according to Vernadsky’s ideas, was initially permeated with the personal and motivational activity of a person.

www.koob.ru

Petrovsky A.V., Yaroshevsky M.G.

Fundamentals of theoretical psychology.

(introductory chapter).

Part 1.

PROLEGOMENA

TO THEORETICAL-PSYCHOLOGICAL

RESEARCH.

Part 2.

BASIC CATEGORIES

PSYCHOLOGY.

Part 3.

METAPSYCHOLOGICAL

Part 4.

EXPLANATORY

PRINCIPLES OF PSYCHOLOGY.

Part 5.

KEY ISSUES

(instead of conclusion).

Literature.

From the authors

The book offers readers (senior-year students of pedagogical

calls and psychological faculties of universities, as well as graduate schools

there departments of psychology) a holistic and systematized consideration

the foundations of theoretical psychology as a special branch of science.

The textbook continues and develops the issues, containing

Psychology, 3rd ed., 1985; Yaroshevsky M.G. Psychology of the XX century

tiya, 2nd ed., 1974; Petrovsky A.V. Questions of history and theory of psycho-

logy. Selected works, 1984; Petrovsky A.V., Yaroshevsky M.G. Is-

theory of psychology, 1995; Petrovsky A.V., Yaroshevsky M.G. Story

and theory of psychology, in 2 volumes, 1996; Yaroshevsky M.G. Historical

skaya psychology of science, 1996).

The book covers: the subject of theoretical psychology, psychological

chological cognition as activity, historicism of theoretical

basic problems of psychology. In its essence, "Fundamentals of Theoretical

psychological psychology" is a textbook intended for completing

teaching a full course of psychology in higher educational institutions.

Introductory chapter "Theoretical psychology as a field of psychology"

chesical science" and chapters 9, 1 1, 14 were written by A.V. Petrovsky; chapter 10 -

V.A. Petrovsky; chapters 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17-

M.G. Yaroshevsky; final chapter "Categorical system -

core theoretical psychology" was written jointly by A.V. Petrovsky,

V.A. Petrovsky, M.G. Yaroshevsky.

The authors will gratefully accept comments and suggestions,

which will contribute to further scientific work in the field of technology

oretic psychology.

Prof. A.V. Petrovsky

Prof. M.G. Yaroshevsky

Theoretical psychology as a field of psychological science

(introductory chapter)

Subject Subject of theoretical psychology - self-referential

theoretical lecture of psychological science, identifying and using

psychology following its categorical structure (protopsy-

chemical, basic, metapsychological, extra-

nism, systematicity, development), key problems arising

on the historical path of development of psychology (psychophysical, psychological

hophysiological, psychognostic, etc.), as well as the psycho-

logical cognition as a special type of activity.

The term "theoretical psychology" is found in the works of many

scientific industry.

Elements of theoretical psychology included in the context as

general psychology and its applied branches are presented in

works of Russian and foreign scientists.

Many aspects concerning the nature and

structures of psychological cognition. Self-reflection of science of technology

suffered during crisis periods of its development. So, on one of the rub-

history, namely at the end of the 19th - beginning of the 20th centuries,

Discussions arose about what method of education

psychology should be guided by acceptance - either by what is accepted

taken in the natural sciences, or what relates to culture. IN

Subsequently, issues related to

entire subject area of psychology, in contrast to other sciences and specialties

digital methods for its study. The following were repeatedly touched upon:

topics such as the relationship between theory and empirics, the effectiveness of volume

explanatory principles used in the spectrum of psychological

problems, the significance and priority of these problems themselves, etc.

The most significant contribution to enriching scientific ideas about

the originality of psychological science itself, its composition and structure

contributed by Russian researchers of the Soviet period P.P. Blonsky,

L.S. Vygotsky, M.Ya. Basov, SL. Rubinstein, B.M. Teplov. However

its components have not yet been isolated from the contents of the

personal branches of psychology, where they existed with other mathematics

rial (concepts, methods of study, historical information -

mi, practical applications, etc.). So, S.L. Rubinstein in

in his major work “Fundamentals of General Psychology” gives a

elaboration of various solutions to the psychophysical problem and consideration of

Reveals the concept of psychophysiological parallelism, mutual

action, unity. But this range of questions does not appear as a precursor.

method of studying a special branch, different from general psychology, which

which is primarily addressed to the analysis of mental processes and

states. Theoretical psychology, therefore, did not act

for him (as well as for other scientists) as a special integral

no scientific discipline.

The peculiarity of the formation of theoretical psychology in

the present time is a contradiction between its already established

representation as an integral area, as a system of psychological

eliminate in this book. At the same time, if it were named

"Theoretical psychology", then this would imply completeness

the formation of the area designated in this way. In fact

However, we are dealing with the “openness” of this scientific field for

inclusion of many new links into it. In this regard, it is advisable

but to talk about “the foundations of theoretical psychology”, meaning

further development of the problem, ensuring the integrity

ity of the scientific field.

In the context of theoretical psychology, the problem of co-

the relationship between empirical knowledge and its theoretical generalization.

At the same time, the process of psychological cognition itself is considered

as a special type of activity. Hence, in particular, the following arises:

the problem of the relationship between objective research methods and

self-observation data (introspection). Arose repeatedly

the theoretically complex question of what actually

Introspection reveals whether the results of introspection can be

be considered on a par with what can be acquired through objective measures

todami (B.M. Teplov). Doesn't it turn out that, looking into the world?

By the way, a person is not dealing with the analysis of mental processes and co-

standings, but only with the outside world, which is reflected in them

and presented?

An important aspect of the branch of psychology under consideration is

improve its predictive capabilities. Theoretical knowledge is

is formed by a system of not only statements, but also predictions based on the field

water for the emergence of various phenomena, transitions from one

statements to another without direct appeal to the feeling

personal experience.

Separation of theoretical psychology into a special field of scientific research

knowledge is due to the fact that psychology is capable of its own

forces, relying on their own achievements and guided by their own

natural values, to comprehend the origins of one’s formation,

development prospects. We still remember those times when “methodology

solved everything,” although the processes of emergence and application of the method

ologies could have nothing to do with psychology, society. Many have up to

There is still a belief that the subject of psychology and its fundamental

areas of extrapsychological knowledge. A huge number of common

methodological developments devoted to the problems of financial

activity, consciousness, communication, personality, development, written fi-

losophists, but at the same time addressed specifically to psychologists. Afterbirth-

they were charged with a special vision of their tasks - in the spirit

quite appropriate at the end of the 19th century the question “Who and how developed

learn psychology?", that is, in search of those areas of scientific knowledge

science (philosophy, physiology, theology, sociology, etc.), which

Some would create psychological science. Of course, the search for psycho-

gey in itself of the sources of its growth, “branching”, flourishing

and the emergence of the sprouts of new theories would be absolutely unthinkable

outside the appeal of psychologists to special philosophical, cultural

rological, natural science and sociological works.

However, despite the importance of the support provided

psychology are non-psychological disciplines, they are not capable of

change the work of self-determination of psychological thought. Theo-

rhetic psychology responds to this challenge: it forms the

times yourself, peering into your past, present and future.

Theoretical psychology is not equal to the sum of psychological theories

riy. Like any whole, it represents something painful

neck than the collection of parts that form it. Various theories and con-

concepts within theoretical psychology conduct a dialogue with each other

home, are reflected in each other, discover in themselves the general and special

something that brings them together or alienates them. Thus, before us is the month-

then the “meetings” of these theories.

Until now, none of the general psychological theories could

declare itself as a theory truly general in relation to

approach to cumulative psychological knowledge and the conditions for its acquisition

retention. Theoretical psychology is initially focused on

building a similar system of scientific knowledge in the future. At that

time as material for the development of special psychological

History of psychology

gical science

and historicism theoretically

skoy psychology