Mentor. Teacher of Tsarevich Alexei Romanov: diaries and memoirs. The Tsarevich's Last Teacher: The Story of Charles Gibbs Tsarevich Alexei's Teacher

The book is dedicated to Charles Sidney Gibbs, who for ten years was an English teacher to the children of Emperor Nicholas II and mentor to Tsarevich Alexei.

The book includes Gibbs's diaries, which had never been published anywhere before, letters to his aunt Kate, where he describes interesting details of the life of the Royal Family in exile, Gibbs' memories of the Royal Family, written by him in July 1949 in Oxford. The publication also includes two books by English authors John Trewin and Frances Welch, telling about Sidney Gibbs. They were published in London in 1975 and 2002.

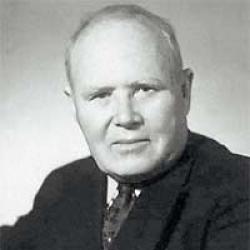

It is interesting where life leads, if you look from the point of a person’s birth to the last point of earthly existence. It is certain that the parents of Charles Sidney Gibbs, rejoicing at his birth on January 19, 1876 in Rotherham, England, did not imagine that he would end his days as an Orthodox priest and monk, Archimandrite Nicholas, and his life would be connected with the life of the family of Nicholas II, whose members would be glorified by the Russian Orthodox Church as saints...

In 1901, Charles Sidney Gibbs moved to Russia, and in 1908 he was invited to teach English to the royal children. “The Grand Duchesses were very beautiful, cheerful girls, simple in their tastes and pleasant to talk to. They were quite smart and quick to understand when they could focus. However, each had its own special character and its own talents,” he would later recall.

After some time, he also became the “mentor” of the heir Alexei Nikolaevich second with Pierre Gilliard.

As Tatyana Kurepina, one of the translators of the book, noted, from a person who knew the Royal Family well, from some everyday everyday moments one can imagine the life of the Family. It is these moments, which at one time seemed insignificant, that years later become a historical document.

“The lesson lasted 15 minutes. He ( Tsarevich) constantly made whips, and I helped him. He spoke a little English and at the end of the lesson, he finally concentrated and was not so shy. He has a cute little face and a very charming smile” (From the book “Mentor. Teacher of Tsarevich Alexei Romanov”).

Over the ten years that Gibbs was close to the Royal Family, he became devoted to all its members. He was next to them and after 1917, he voluntarily went to Tobolsk for them.

Readers have the opportunity to see the Royal Family through the eyes of a person who knew its members well.

“Testimonies about the Empress, even brief ones, will not be complete without mentioning Her piety and piety. These qualities were inherent in her from childhood, and the transition to the Orthodox Church served to strengthen all of her religious instincts. (...) She always strived for a simple life and became Orthodox with all her heart. The dogmas of Orthodoxy became leading in her life. Being devoted to Orthodoxy, the Empress, until her death, scrupulously observed the fasts and holidays of the Holy Church. Before all important events, She and Her husband confessed and received communion. (...) At the same time, I must add that She behaved without any fanaticism and with the greatest moderation” (From the book “Mentor. Teacher of Tsarevich Alexei Romanov”).

You read a book, look at photographs, and what happened almost 100 years ago becomes very close. The publication, according to Kirill Protopopov, one of its author-compilers, includes photographs from the Gibbs archive that have not previously been published. For example, a photograph of the Tsarevich’s camp bed in Tobolsk, or a carriage taking the Empress at 5 am from Tobolsk to Yekaterinburg...

It was at this bedside of the sick Alexei that Charles Sydney Gibbs sat when the Empress was forced to leave her children and follow her husband. Gibbs accompanied the children on their trip to Yekaterinburg, but then they were taken away, and the accompanying people were not allowed to join them...

And after their deaths, Gibbs remained nearby: after the whites came to Yekaterinburg, he helped investigator Nikolai Sokolov in his investigation into the death of the Royal Family.

“I always felt that the world, in general, never took Emperor Nicholas II seriously, and I often wondered why. He was a man who had no base qualities. I think this can mostly be explained by the fact that He seemed completely incapable of inspiring fear. He knew very well how to maintain his dignity. No one could even imagine taking liberties with the Emperor. (...) He did not put himself above others, but at the same time he was filled with calmness, self-control and dignity. The main thing that He inspired was awe, not fear. I think it was his eyes that caused it. Yes, I'm sure it was his eyes, they were so beautiful. (...) His eyes were so clear that it seemed that He was opening his whole soul to your gaze. A simple and pure soul, which was not at all afraid of your searching gaze. No one else could look like that.” (From the book “Mentor. Teacher of Tsarevich Alexei Romanov”).

Later, in Harbin, Gibbs accepted Orthodoxy, monasticism and priesthood. Tatyana Manakova, one of the authors and compilers of the book: “I was shocked by the conversion to Orthodoxy of Charles Sidney Gibbs. Still, not so fast after the death of the Royal Family - in 1934. He consciously took this step for many years. As Gibbs himself writes, he was impressed by the attitude towards Orthodoxy of the Royal Family; of course, he was also pushed by their humility during their suffering in prison. But it must be said that he had an interest in theology even in his student years. And his father wanted Gibbs to become a priest of the Anglican Church. But many years later he became an Orthodox priest.”

“It seems to us that the events that we are now remembering happened a long time ago. However, people are alive who remember those who personally knew the Royal Family,” noted Tatyana Manakova.

In Harbin, Gibbs met a boy, Georgiy Pavelev, who was left without parents, and adopted him. One of George’s sons, also Charles Gibbs, is now alive and is the custodian and copyright holder of the archival materials of his grandfather, who carefully preserved the living memory of the Royal Family all his life. Living by this memory.

Christmas 1924. Harbin. In the center are Georgy Pavelev and Charles Sydney Gibbs. Photo: st-tatiana.ru

One of the last friends of Father Nicholas (Gibbs), David Beatty, came to his adopted son George a few days after his death. In the bedroom of the deceased, he saw an icon given to Father Nicholas by the Royal Family. “George said that three days before the priest’s death, the icon dimmed and then began to glow.

"Icon really glowed... - recalls Beatty with a barely noticeable smile. “I won’t say anything more.”

At that moment, David Beatty thought that Father Nikolai had finally found himself where he wanted to go. “Father Nikolai was looking forward to the hour when he would finally be able to see the Royal Family again. And I realized that this moment had come.” (From the book “Mentor. Teacher of Tsarevich Alexei Romanov”)

In 1917, he fell into the vortex of the Russian October events. Charles Sydney Gibbs. Being a subject of the English crown, he turned out to be one of the most devoted servants of the Russian Tsar.

"Saucer Machines"

In 1901, the son of a bank manager and a graduate of one of the British universities went to distant Russia. Charles Gibbs was a B.A.. And St. Petersburg attracted him as a city of theater, ballet, museums and exhibitions. The impetus was an advertisement in the newspaper that English teachers were needed in the city on the Neva. But in reality, as he writes American Gibbs biography researcher Christina Benag, all those almost 20 years that Charles spent in Russia became a spiritual pilgrimage for him.

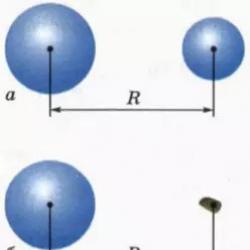

Gibbs taught English to the royal children for 10 years. As he later wrote in his memoirs, for his first visit to the palace he put on a tuxedo. Having passed through the enfilade of formal rooms, Charles was struck by the asceticism of the classroom: a table, chairs, a blackboard, a shelf with books and many icons on the walls. Above the classroom, on the floor above, there were children's rooms, where the grand duchesses slept on hard beds and washed themselves with cold water. The family accepted simple food. Cakes were rarely served for tea. Tsarevich Alexei was brought cabbage soup and porridge every day from the soldiers' kitchen of the Consolidated Regiment. He ate everything, saying: “This is the food of my soldiers.” Younger girls often wore the dresses and shoes of their elders. The emperor himself, a decade after the wedding, wore civilian suits from the time of the groom. The Englishman was impressed that His Majesty did without a personal secretary: all the papers on which the royal seal was to be affixed were Nicholas II I read it myself. He had a good memory and spoke fluent English, French and German.

Senior Princess Olga Outwardly, she looked no more like an emperor than anyone else; she had an almost perfect ear for music. Tatiana I was immediately struck by its beauty. Because of her strict character, she was called the “governess.” Maria She loved to draw, she had huge blue eyes - “Saucer machines”. Younger Anastasia after classes she ran into the garden to pick and give flowers to Sid, as Charles was called in the family.

After the February Revolution, the family found themselves in the Alexander Palace under house arrest. The children lay with a fever, covered with sheepskin coats, because the family had been “cut off” electricity, heat and even water; it had to be taken from an ice hole. Nicholas II felled dry trees in the park and sawed them for firewood. At the end of March, family members dug up a vegetable garden on the palace lawn and planted vegetables. From the very first day of imprisonment, the commission appointed by the Provisional Government did not stop interrogating the Tsar and Tsarina. But no facts indicating high treason could be found.

When the decision was made to send the royal family to Tobolsk, Gibbs obtained permission to follow. Because of this, he quarreled with his fiancee Miss Cade, she was a member of the English Teachers Guild, like Gibbs himself. Having covered several thousand kilometers, Gibbs kissed the hand of the emaciated and gray-haired empress. In Siberia, prisoners could only breathe air by going out onto the balcony. Alexandra Fedorovna knitted socks, darned clothes... and wrote: “We must endure, be cleansed, be reborn!”

The Bolsheviks, having come to power, transported the royal family to Yekaterinburg. Gibbs accompanied his students, but there he was forbidden to follow the Romanovs. Sid watched the 20-year-old Princess Tatiana drowning ankle-deep in mud - in one hand she was holding a heavy suitcase, and in the other Alexei’s beloved dog. The boy himself had difficulty moving due to illness. The prisoners were settled in a house that belonged to businessman Ipatiev. In those days, Tatyana emphasized in one of her books: “Believers in the Lord Jesus Christ before death maintained a wonderful calm of spirit. They hoped to enter into a different, spiritual life, which opens up for a person beyond the grave.”

Nicholas II with his daughters Olga, Anastasia and Tatiana (Tobolsk, winter 1917) Photo: Commons.wikimedia.org

Prayer for enemies

They entered a new life as a family. They were shot in the middle of the night in the basement.

The wounded princesses and the prince were finished off with bayonets. Then they were taken 20 km from the city, to Ganina Yama, where they disposed of the corpses using fire and sulfuric acid. The white troops, and with them Gibbs, entered the city shortly after the crime. Charles helped the investigation reconstruct the circumstances of the crime and listened to the testimony of witnesses. On Ganina Yama, along with a dropped earring, a severed finger and scraps of clothing, Sid saw a piece of multi-colored foil from a children's set, which the Tsarevich liked to carry in his pocket. For a second, Charles closed his eyes... Then he took out from his pocket a tattered piece of paper with a poem, which the princesses had often re-read lately, and in one of the lessons they translated into English. At the end it was: “And at the threshold of the grave, Breathe into the mouths of Your servants Superhuman powers, Pray meekly for your enemies.”

God gave them these superhuman powers. Senior Princess Olga in a letter from captivity she wrote: “Father asks me to tell everyone not to take revenge for him - he has forgiven everyone and is praying for everyone... it is not evil that will defeat evil, but only love.” It was then that Gibbs felt that he was close to a great spiritual mystery. There was only one step left, which he took in the Russian church in Harbin (a mass of Russian emigrants had accumulated in this Chinese city): here Charles converted to Orthodoxy. The sacrament of confirmation was performed by Archbishop Nestor (Anisimov). He was wearing a vestment worn to holes, donated many years ago by the All-Russian shepherd John of Kronstadt. Charles received the name Alexey - in honor of the Tsarevich. Afterwards he wrote to his sister Winnie that he felt as if he had returned home after a long journey. A year after accepting Orthodoxy, Bishop Nestor tonsured Gibbs a monk with the name Nicholas - in honor of the murdered king. After some time, he accepts the priesthood and becomes Father Nicholas. Returning to England, he took with him photographs of the imperial family, notebooks of the princesses and other things that he managed to save in Tobolsk and Yekaterinburg. But the main treasure that he carried in his heart was faith. In London, he was elevated to the rank of archimandrite and headed an Orthodox parish. Then he moved to Oxford, where he bought a small house with his savings. Here he built a house church in honor of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker. In one of the rooms he also organizes a miniature museum dedicated to the royal family. Services in the house church were constantly attended by 60 people. Information came from Russia that in Yekaterinburg, believers, despite the danger, every year on the day of the murder of the royal family come at night to a prayer service at the Ipatiev House. At such moments, blood suddenly began to flow through the white walls. The authorities repainted the building, but the phenomenon repeated itself.

The royal family also gave a sign from heaven to Father Nicholas. The icon, which belonged to the royal martyrs and hung at the archimandrite’s home, was renewed and sparkled with bright colors. At that moment, the 87-year-old monk was already mortally ill. Father Nikolai (Gibbs) reposed on March 24, 1963. His grave in the cemetery in Oxford is distinguished from others by the Orthodox cross engraved on it.

Despite many publications about the last years of the family of Emperor Nicholas II, many blank spots remain in this area. Very little has been written about the people who did not leave the royal family until the day of its tragic death. Among them is the Englishman Charles Sydney Gibbs, a man of complex and interesting fate. March 24 marked 40 years since his death.

Arriving in Russia as a young man, Gibbs evolved over the years from an inexperienced English teacher to a confidant of the family of Nicholas II.

The years spent with the imperial family had a tremendous impact on his entire life and worldview. Throughout his long life, he remained faithful to the memory of the royal family and managed to preserve many relics of great value for Russian history. Having gone through a difficult path to the Orthodox faith, Charles Gibbs made a significant contribution to the spread of Orthodoxy in Great Britain.

Charles Sidney Gibbs came to Russia in the spring of 1901 as an English teacher. Over time, he becomes a member and then president of the St. Petersburg Guild of English Teachers.

One day, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna was told that her daughters spoke English poorly (with a Scottish accent), and Gibbs was recommended to her. In the autumn of 1908, he arrived in Tsarskoe Selo and was introduced to his future students - the Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana, who were then 13 and 11 years old. Later, nine-year-old Anastasia joined the classes.

Many years later, Gibbs recalled: “The Grand Duchesses were very beautiful, cheerful girls, simple in their tastes and pleasant to talk to. They were quite smart and quick to understand when they could focus. However, each had its own special character and its own talents.”

Three years later, the Empress asked Gibbs to mentor the prince in teaching him English. Alexei was then eight years old. Before that, he often walked into the classroom - “a tiny kid in white tights and a shirt bordered with blue and silver Ukrainian embroidery.” “He used to come into class at 11 o'clock, look around and then seriously shake hands. But I didn’t know a word of Russian, and he was the only child in the family who had not had an English nanny since birth, and he didn’t know a single word of English. In silence we shook hands and he left.”

When Gibbs began working with Alexei, the boy was pale, nervous and weak due to an worsening illness. Several months passed until an atmosphere of mutual understanding and trust was achieved. Alexey felt more free and tried to speak more English.

It so happened that on the day of the king's abdication, Gibbs left the palace, going to the city to find out the news. However, he did not manage to return back immediately. The intervention of the British ambassador, who wrote a letter to the head of the Provisional Government asking him to allow Gibbs to return to the palace, did not help either. But there was no positive answer.

Gibbs began sending letters to the palace, in which he carefully reported news about the situation in the city. He was allowed to return to the palace only on August 2, 1917 - the day after the imperial family left him. Gibbs decided to follow the people who had become close to him.

At the beginning of October he managed to reach Tobolsk. He barely managed to get on the last ship leaving Tyumen before the end of navigation. He also became the last of those who managed to obtain permission to join the royal family.

According to Gibbs' recollections, he was amazed to see how Alexandra Fedorovna had aged over the past five months. At the same time, Alexey looked healthier than usual.

Everyone greeted Gibbs with joy. He brought fresh, although not very encouraging, news, messages from friends and relatives, new books, and with his arrival it became much more fun to spend the long winter evenings. Gibbs continued his studies with the three younger princesses and Alexei. He then kept the two notebooks in which Maria and Anastasia wrote dictations throughout his life.

Before Christmas, the Empress asked Gibbs to write a letter on his behalf to Margaret Jackson, her former governess, to whom she was deeply attached and with whom she corresponded for many years, confiding her joys and sorrows. Now, with the help of this letter, the queen wanted to give the English side detailed information about the situation in Tobolsk, without revealing its true author and addressee. Gibbs's drafts preserve his attempts to convey the main points, masked by the style of private correspondence: “You must have read in the newspapers that many changes have taken place. In August, the Provisional Government decided to move the residence from Tsarskoye Selo to Tobolsk.” Then there is a description of the city, the rooms in the governor’s house and the details of everyday life, and then: “You haven’t written for a hundred years, or maybe the letters haven’t arrived. Try writing again, and maybe the next one will reach its destination. Write news about everyone: how they are, what they are doing. I heard that David returned from France, like his mother and father? And cousins, are they at the front too?” David is the Prince of Wales, and Alexandra Feodorovna was sure that his name would tell Margaret that she needed to deliver this letter to the queen.

But the answer never came. Later, Gibbs managed to find out that the letter sent from Tobolsk by diplomatic mail reached Petrograd, but there its trace was lost. There is no such letter in the English Royal Archives, although there are other references to Gibbs there.

In his memoirs, Gibbs writes about the day when the Emperor and Empress learned that they were being taken away from Tobolsk. Although they were not told where they were going, everyone thought it was to Moscow. “They spoke little... It was a solemn and tragic parting.” At dawn, all the servants gathered on the glassed-in veranda. “Nicholas shook everyone’s hand and said something to everyone, and we all kissed the Empress’s hand.”

To Ekaterinburg, Gibbs, Pierre Gilliard (a French teacher), Baroness Buxhoeveden, Mademoiselle Schneider and Countess Gendrikova traveled in a fourth-class carriage, which was not much different from a heated freight carriage.

The train stopped before reaching the station. Gibbs looked out of the window: several droshky stood on the embankment, waiting for passengers. He and Gilliard saw how the princesses, stuck in the mud, tried to climb onto a slippery embankment. Tatiana carried heavy suitcases in one hand, holding her small dog in the other. Sailor Nagorny came up to help, but the guards rudely pushed him away. The droshky left and the train arrived at the station. General Tatishchev, Countess Gendrikova and Mademoiselle Schneider were taken away by guards and were never seen again.

At five in the evening, those remaining were told that they could go wherever they wished, but they were not allowed to be with the imperial family. In the end they decided to send them back to Tobolsk, but the advance of the White Army prevented these plans, and they were left in Yekaterinburg. They spent about ten days in the carriage. Every day they walked into the city, usually one or two at a time, so as not to attract attention, and passed by the Ipatiev House, hoping to catch a glimpse of someone from the royal family. One day, Gibbs saw a woman's hand opening a window and thought it might be Anna Demidova. Another day, Gibbs and Gilliard, walking near the house, saw the sailor Nagorny, who was being led by soldiers with bayonets. He noticed them too, but pretended not to recognize them. Four days later he was shot.

Gibbs and Gilliard were forced to leave for Tyumen, from where they regularly called the British consulate, trying to find out something new about the situation of the imprisoned family and about the rapidly advancing White Army, on which high hopes were placed.

On July 26, the Whites took Yekaterinburg. Having barely learned about this, Gibbs and Gilliard went there from Tyumen. In Ipatiev's house they saw terrible destruction. Everything spoke of a murder that had taken place here. But what then did the official statement of the Soviet government mean that the empress and heir were in a safe place? What about the daughters and servants who were not mentioned? Gilliard was inclined to hope for something, Gibbs was more skeptical.

In September he settles in Yekaterinburg, where he gives private lessons. Since he was known at the British Consulate, he was introduced to Charles Eliot, the British High Commissioner to Siberia.

Gibbs followed the investigation into the murder of the royal family, and he was always invited as one of those people who could identify the objects found. He copied the testimony of witnesses, even those who conveyed only rumors or secondary information.

At this time, the British High Commissioner offered him the post of secretary on his staff. Gibbs immediately agreed to this proposal - he was already very tired and missed his compatriots.

The British mobile headquarters was located in Omsk and was located in a large railway carriage, adapted for housing and work. Arriving in Omsk, Gibbs learned that the headquarters was leaving for Vladivostok.

On February 27, already in Vladivostok, Gibbs met with General Mikhail Dieterichs, with whom he worked during the first investigation in Yekaterinburg. Dieterichs told him that he had brought with him all the materials and things he had collected. He intended to send them to England. That same evening they met with the captain of the ship on which this valuable cargo was supposed to be sent. The items, including some rather bulky ones, such as the Empress's wheelchair, were described.

In the summer of 1919, Gibbs assisted investigator Sokolov in his investigation into the murder of the imperial family. He again visits the Ipatiev House, the mines where they looked for the bodies of the royal martyrs. In a letter to his aunt Kate, Gibbs talks about the touching and sad service in memory of members of the imperial family, which took place on July 17, 1919, the anniversary of their death.

Gibbs already really wanted to return to England. However, his future was unclear and alarming. At times he must have felt like a secret agent, as Dieterichs and Sokolov entrusted him with information they both considered dangerous and material evidence they believed posed a threat.

Sokolov and Dieterichs met with Gibbs again in Chita on Christmas Day, January 7, 1920. They said their lives were in danger because they had information about the killers. Dieterichs brought with him a small box covered with dark lilac leather that had previously belonged to the empress. “I want you to take this box with you now. It contains all their remains,” he told Gibbs.

The British mission went to Harbin. Dieterichs handed some of the things to the head of the mission, Lampson, assuming that he would hand them over to Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich or General Denikin. However, from Harbin, Lampson and some of his employees, including Gibbs, were sent to Beijing. From there, in February 1930, Lapson made a report to London and asked that the materials be taken into custody. A negative answer came in March. At this time, Sokolov and Dieterichs were also in Beijing. They managed to meet with the French general Yanin and ask him for help. Yanin said that “he considers the fulfillment of the mission that we entrusted to him as a duty of honor to a faithful ally.” According to some reports, the box given to the general is still kept in his family.

Shortly afterwards the British Mission to Siberia ceased to exist and Gibbs' service ended. It seemed that he was now free to return to England, but his mood changed. He remembered how painfully Nicholas II perceived the British reaction to his abdication, the joy of the British Parliament and the congratulatory telegram to the Provisional Government. Gibbs's home country did not provide refuge to the imperial family. And he didn't want to go back there.

Gibbs spent seven years in Harbin. In 1924, he began to receive letters in which he was asked if he knew about the surviving members of the royal family. A London law firm asked him to identify the woman in the photograph. Gibbs sent a cautious reply: the woman bore some resemblance to Grand Duchess Tatiana, although the eyes - the most memorable part of Tatiana's face - were darkened in the photograph, and the woman's hands seemed too large and wide. Friends and relatives of the Romanovs began to bombard him with articles that talked about the grand duchesses who allegedly escaped death, and demanded to comment on this, but Gibbs preferred to remain silent.

Despite his then renewed interest in Buddhism, Gibbs often attended the Russian church, and his friends included priests and parishioners who had special respect for him because of his connections to the royal family. Gibbs made a pilgrimage to Beijing, where he visited the shrine with the relics of members of the imperial family, buried there after General Dieterichs, risking his own life, brought them from Siberia and entrusted them to the Russian Orthodox Mission. The coffins were placed in the crypt of the cemetery church that belonged to the mission. Even before Gibbs's visit, the relics of Grand Duchess Elizabeth and nun Barbara were transported to Jerusalem for burial in the Church of St. Mary Magdalene, where the Venerable Martyr Elizabeth wished to be buried.

Having made this pilgrimage to Beijing, Gibbs decides to return to England. His family greeted him as joyfully as if he had risen from the dead.

In September 1928, he entered a pastoral course at Oxford and began to carefully study the works of the holy fathers. At that time, there was a debate in England about simplifying church language, which caused serious damage to the authority of the Church. Gibbs understands that he will not serve in the Anglican Church. Continuing to be registered with the customs department, Gibbs was forced to return to Harbin in October 1929. However, in mid-September 1931, hostilities began between the Chinese nationalists and the Japanese army based in Mukden. In 1932, Japan captured Manchuria, and Gibbs was left without a job.

According to some reports, he spent one year in a Japanese Buddhist monastery, but this did not relieve him of his feelings of disappointment and spiritual emptiness.

He increasingly remembered the spiritual strength that helped the members of the royal family maintain courage and dignity in the midst of all the terrible trials that befell them. Gibbs remembered a poetic prayer composed by Countess Gendrikova. The family often read this prayer together:

Send us, Lord, patience

In a time of violent dark days

To endure popular persecution

And the torture of our executioners.

Give us strength, O righteous God,

Forgiving one's neighbor's crime

And the cross is heavy and bloody

To meet with Your meekness.

And in the days of rebellious excitement,

When our enemies rob us,

To endure shame and insults,

Christ the Savior, help.

Lord of the world, God of the universe,

Bless us with your prayer

And give rest to the humble soul

At an unbearably terrible hour.

And at the threshold of the grave

Breathe into the mouths of your slaves

Superhuman powers

Pray meekly for your enemies.

Gibbs was close to a great secret that he was only now able to recognize. He quickly goes to Harbin to become Orthodox. At baptism, Gibbs took the name Alexy - in honor of the prince.

Gibbs's spiritual father was Archbishop Nestor of Kamchatka and Peter and Paul. He was a missionary who brought the light of the Gospel to the pagan Kamchadals. He came to Harbin in 1921, fleeing the Red Terror. And here he also showed his energy and experience, organizing canteens for the poor, orphanages and hospitals for the emigrant community.

Gibbs tried to express his feelings in one of his letters to his sister: it was “almost like returning home after a long journey.”

In December 1935, Gibbs became a monk. In monasticism he was given the name Nikolai. That same year he became a deacon and then a priest. All this time, he discussed with his mentor Archbishop Nestor the possibility of creating an Orthodox monastery in England. The Archbishop blessed him to go to the Russian Orthodox Mission in Jerusalem for one year to get to know monastic life better.

The Jerusalem Mission was founded at the end of the 19th century to provide assistance to Russian pilgrims, who at that time were arriving in the Holy Land in large numbers. After 1917, the flow of pilgrims from Russia dried up, but monks and nuns remained in the Mission. The remains of Grand Duchess Elizabeth and nun Varvara were buried here.

In 1937, Hieromonk Nicholas (Gibbs) returned to England. However, he fails to found a monastic community there. In 1938, Archbishop Nestor, who was touring Europe, visited London. He ordains Father Nicholas as an archimandrite and places a miter on him.

In 1941, Father Nikolai was invited to Oxford to organize a parish there. Many emigrants - translators, journalists, scientists - came to this university town. Services were held in an ancient cathedral located on the territory of one of the colleges. After the end of the war, students returned to college, and Father Nicholas began searching for a permanent location for the church. He found three suitable cottages and invested most of his savings into their purchase. In 1946, a temple in honor of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker was consecrated in one of these buildings.

When the troubles associated with the repairs were over, Father Nikolai took out an amazing collection of things related to the imperial family that he had kept for almost 30 years. Most of these things were taken from Ipatiev's house in 1918 with the permission of General Dieterichs.

He hung icons on the walls of the temple, some of which were given to him by members of the imperial family, and some of which he saved from the Ipatiev House. In the center of the temple, Father Nikolai hung a chandelier in the form of pink lilies with metallic green leaves and a branch of violets. This chandelier used to hang in the bedroom in the Ipatiev House.

In the altar, Father Nicholas placed boots that belonged to Nicholas II, which he captured from Tobolsk to Yekaterinburg, believing that the Tsar might need them, but he was no longer destined to see the Tsar.

And at every service he remembered the emperor, empress, prince and grand duchesses.

Father Nikolai hoped to found a museum using the things he had and then attract other people who kept the memory of the royal family, as well as open a Russian cultural center in London. But lack of funds did not allow him to do this.

However, he converted the library room into a miniature museum. Here he placed photographs that he took in Tsarskoe Selo, Tobolsk and Yekaterinburg; study books for Maria and Anastasia; several menu sheets from Tobolsk with images of the imperial cross; a pencil case that belonged to the prince and a bell with which he played; a copper coat of arms from the imperial yacht “Standard” and many other things that he saved.

In 1941, when Gibbs arrived in London, he was already 65 years old and needed an assistant. A few years later, he talks about his situation in a letter to Baroness Buxhoeveden: “It is already four years since I invited the son of Stolypin’s Minister of Agriculture (Krivoshein) to come to me from Holy Mount Athos, where he spent 25 years as a monk after completing his studies at the Sorbonne. .. Father Vasily is now a scientist with a fairly high name... In the second year of his arrival, I organized everything for his ordination to the priesthood... Then he took upon himself all the responsibilities associated with the temple.”

In 1945, Father Nikolai moved to the Moscow Patriarchate. And he was left in painful loneliness. In 1959, the Russian Parish Council decided to move to the House of St. Basil and St. Macrina, founded by Nikolai Zernov. Father Vasily (Krivoshein), who later became archbishop, also moved. Father Nikolai was deeply offended, believing that this would lead to the disintegration of the parish.

However, even in the last years of his life, Father Nikolai was surrounded by friends. One of them, the Catholic Peter Lascelles, attended Anglican, Catholic and Orthodox churches and was well acquainted with Orthodox services. He became very attached to Father Nikolai and helped him in many ways. Their friendship had a huge influence on Lascelles. Already in the 90s, two weeks before his death, he converted to Orthodoxy and was buried in the St. John the Baptist Monastery, founded by Archimandrite Sophronius in Essex.

Another friend of Nikolai's father was David Beatti. They met in 1961, two years before the death of Father Nicholas, at one of the festive events of the Anglican Church. Beatti had just returned from Moscow, where he had been an interpreter at the first British Trade and Industry Fair. They got to talking, and, noticing Beatti’s sympathy for the members of the imperial family, Father Nicholas told him for an hour about his life with them, praising their courage. Only later did Beatti realize that he had been given a great honor, since the prince’s former mentor very rarely spoke about the royal family.

As Beatti recalls, a year before his death, Father Nikolai lost a lot of weight and was quickly losing strength. But “his face was striking... Very rosy cheeks, bright blue eyes and a scraggly snow-white beard reaching to the middle of his chest. He was an interesting and witty conversationalist, his mind was clear. I was amazed by its simplicity and practicality at the same time. Despite his difficult life and unusual appearance, he was a perfect Englishman in his practical approach to things and in his sense of humor... He had a natural authority, he was a man who was admired and not argued with.”

Father Nicholas died on 24 March 1963, aged 87, and was buried in Headington Cemetery, Oxford. As his friends who visited him in these last months said, despite his weakness, he always smiled.

After his death, David Beatti and another friend of Nikolai's father went to his London apartment to find out whether Father Nikolai's archive and things were in danger of being sold off. They were assured that this would not happen, and were invited to the bedroom of Father Nicholas, where an icon hung above the bed - one of those that had once been given to him by the imperial family. Over the years, its colors have faded and faded. But three days before the death of Father Nikolai, the colors gradually began to renew themselves and became bright as before. And it was like a gift to Father Nicholas from the holy passion-bearers, to thank him for his long and devoted service, both during their lives and after their martyrdom.

This is how Tsarevich Alexei’s mentor, the Englishman Charles Gibbs, who followed the royal family into exile, called his transition to the Orthodox faith.

New teacher

One day, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna was told that her daughter did not speak English well enough, and they recommended her a young but promising teacher, Gibbs. In the autumn of 1908, he arrived in Tsarskoe Selo and was introduced to his future students - the Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana, who were then 13 and 11 years old, respectively. Later, nine-year-old Anastasia joined the classes.

Many years later, Gibbs recalled: “The Grand Duchesses were very beautiful, cheerful girls, simple in their tastes and pleasant to talk to. They were quite smart and quick to understand when they could focus. However, each had its own special character and its own talents.”

Three years later, the Empress asked the teacher to study English with eight-year-old Alexei. Before this, the Tsarevich often came into the classroom.

“He... looked around,” Gibbs writes in his memoirs, “and then seriously shook hands. But I didn’t know a word of Russian, and he was the only child in the family who had not had an English nanny since birth, and he didn’t know a single word of English. In silence we shook hands and he left.” Over time, Gibbs managed to win over the boy, who was a little withdrawn due to illness, and he began to make progress in learning English.

After renunciation

On the day of Emperor Nicholas II's abdication, Gibbs went to the city to find out the news. He was no longer able to get back into the palace - no one was allowed into the royal family. Even the intervention of the British ambassador did not help. He was allowed to return to the palace only on August 2, 1917 - the day after the Romanovs left it. Gibbs was determined to follow the people who had become close to him. He became the last of those who managed to obtain permission to join the royal family.

Only at the beginning of October the brave Englishman was able to reach Tobolsk; he barely caught the last ship departing from Tyumen before the end of navigation. For the prisoners, his arrival was a great joy. Gibbs brought fresh, although not very encouraging, news. In his luggage were new books that distracted the prisoners from gloomy thoughts and brightened up the long winter evenings. Charles continued his studies with the three younger princesses and with Alexei. He subsequently kept the two notebooks in which Maria and Anastasia wrote dictations throughout his life.

Parting

In his memoirs, Gibbs writes about the day when the Emperor and Empress learned that they were being taken away from Tobolsk. “They said little... It was a solemn and tragic parting.” At dawn, all the servants gathered on the glassed-in veranda. “Nicholas shook everyone’s hand and said something to everyone, and we all kissed the Empress’s hand.”

To Ekaterinburg, Charles Gibbs, Pierre Gilliard (a French teacher), Baroness Buxhoeveden, Mademoiselle Schneider and Countess Gendrikova traveled in a fourth-class carriage, which was not much different from a heated freight carriage.

Upon arrival in the city, Countess Gendrikova and Mademoiselle Schneider were taken away under guard and were never seen again. They decided to send those who remained back to Tobolsk, but the advance of the White Army prevented these plans, and they were left in Yekaterinburg. They spent about ten days in the carriage. Every day they went into the city, usually one or two at a time, so as not to attract attention, and, passing by the Ipatiev House, they hoped to catch a glimpse of someone from the royal family.

Investigating a murder

On July 26, the Whites took Yekaterinburg. The royal family did not live to see this event for only a few days. When Gibbs entered the Ipatiev House, he saw terrible destruction there. Everything spoke of a murder that had taken place here, although the Soviet government officially announced that the empress and heir were in a safe place.

...In the summer of 1919, Gibbs helps investigator Sokolov in the investigation of the murder of the imperial family. He again visits the Ipatiev House, inspects the mines where they looked for the bodies of the royal martyrs. At times he must have felt like a secret agent, as General Dieterichs and Sokolov entrusted him with information that they both considered dangerous.

On January 7, 1920, on Christmas Day, Mikhail Dieterichs gave Gibbs a small box covered with dark lilac leather that had previously belonged to the Empress. “I want you to take this box with you now. It contains all their remains,” he told Gibbs.

At the royal relics

Together with the British mission, where Gibbs served in recent years, he heads to Harbin. He stayed here for seven years, although he had the opportunity to return to his homeland much earlier. But the policy of the British government did not arouse his sympathy. He remembered how painfully Nicholas II perceived the British reaction to his abdication: the joy of the British Parliament and the congratulatory telegram to the Provisional Government.

Gibbs's homeland did not provide refuge to the imperial family. And he didn't want to go back there. Despite his renewed interest in Buddhism at the time, Charles often attended the Orthodox Church. Among his friends were priests and ordinary parishioners who had special respect for him, knowing about his connections with the royal family.

Gibbs made a pilgrimage to Beijing, where he venerated the relics of members of the imperial family. This became possible thanks to General Dieterichs, who, risking his own life, brought them from Siberia and entrusted them to the Russian Orthodox Mission. The coffins were placed in the crypt of the cemetery church that belonged to the mission. Only after this trip to Beijing does Charles Gibbs finally decide to return to England.

Spiritual path

In September 1928, he entered a pastoral course at Oxford and began to carefully study the works of the holy fathers. But Gibbs knows that he will not serve in the Anglican Church. Continuing to be registered with the customs department, he returned to Harbin in October 1929. The Englishman increasingly thinks about the spiritual strength that helped members of the royal family maintain courage and dignity in the terrible trials that befell them. And he decides to accept Orthodoxy. This happened in 1934. At baptism, Gibbs receives the name Alexy - in honor of the Tsarevich. He expressed his feelings in one of his letters to his sister: it is “almost like returning home after a long journey.”

Charles's spiritual father was Archbishop Nestor of Kamchatka and Peter and Paul, who brought the light of the Gospel to the pagan Kamchadals. Shortly after his baptism, Gibbs took monastic vows with the name Nicholas. That same year he became a deacon and then a priest. All this time, he discussed with his mentor Archbishop Nestor the possibility of creating an Orthodox monastery in England. The Bishop blessed him to go to the Russian Orthodox Mission in Jerusalem for one year in order to become better acquainted with monastic life.

Boots in the altar

Hieromonk Nicholas (Gibbs) returns to England in 1937. However, he fails to found a monastic community there. Soon Archbishop Nestor, who was touring Europe, arrived in London. He ordains Father Nicholas as an archimandrite and places a miter on him.

In 1941, Archimandrite Nicholas was invited to Oxford to organize a parish there. Many emigrants - translators, journalists, scientists - came to this university town. Services were performed in an ancient cathedral located on the territory of one of the colleges. But after the end of the war, the students returned to college, and Father Nikolai had to look for another place for worship.

He found three suitable cottages and invested most of his savings into their purchase. In 1946, a temple in honor of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker was consecrated in one of these buildings. The archimandrite placed icons on the walls of the temple, some of which were presented to him by members of the imperial family. He brought others from the Ipatiev House. In the center of the temple, Father Nikolai hung a chandelier in the form of pink lilies with metallic green leaves. This chandelier used to hang in the bedroom in the Ipatiev House. And in the altar the archimandrite placed boots that belonged to Nicholas II, which he once brought from Tobolsk to Yekaterinburg, believing that the sovereign might need them.

Royal relics

Father Nikolai, having a large collection of things that belonged to the Romanov family, planned to found a museum of the royal martyrs, as well as open a Russian cultural center in London. But due to lack of funds, he was unable to implement this plan. But still he managed to arrange a mini-museum in a small library room. The exhibition included photographs taken in Tsarskoe Selo, Tobolsk and Yekaterinburg, study books from Maria and Anastasia, and several menu sheets from Tobolsk with images of the imperial cross. Among the royal things one could see a pencil case that belonged to the Tsarevich and a bell with which he played, as well as a copper coat of arms from the imperial yacht “Standard”.

Faithful friends

In the last years of his life, Father Nikolai was surrounded by friends and associates. One of them is Catholic Peter Lascelles. Attending services in the church of his friend the archimandrite, he became very attached to him. Their friendship had a huge influence on Lascelles. Already in the 90s, two weeks before his death, the once convinced Catholic converted to Orthodoxy and was buried in the St. John the Baptist Monastery in Essex.

Another friend of Nikolai's father was David Beatti. They met in 1961, two years before the death of the archimandrite. Beatti had just returned from Moscow, where he had been an interpreter at the first British Trade and Industry Fair. They got to talking, and, noticing Beatti’s sympathy for the members of the imperial family, Father Nicholas spent an hour telling him about the amazing spiritual qualities of the emperor, empress and their children.

Only later did Beatti realize that he had been given a great honor, since the prince’s former mentor very rarely spoke about the royal family.

The last gift

A year before his death, Father Nikolai lost a lot of weight and began to quickly lose strength. But as David Beatti recalls, “his face was striking... Very rosy cheeks, bright blue eyes and a scraggly snow-white beard that reached the middle of his chest. He was an interesting and witty conversationalist, his mind was clear. I was amazed by its simplicity and practicality at the same time. Despite his difficult life and unusual appearance, he was a perfect Englishman in his practical approach to things and in his sense of humor... He had a natural authority, he was a man whom one admires and does not argue with.”

Father Nicholas died on 24 March 1963, aged 87, and was buried in Headington Cemetery, Oxford. As friends who visited the priest in the last months of his life said, despite his weakness, he always smiled.

...After his death, David Beatti, together with another friend of Father Nicholas, went to his London apartment to find out if there was any danger to the archive and things of the Bishop. After making sure that all the property was safe and sound and would not be sold under the hammer, they went into Father Nikolai’s bedroom. Above the bed hung an icon, given to Charles Gibbs many years ago by the royal family.

Over time, its colors faded and faded. But three days before the death of the priest, the colors began to gradually renew and became as bright as before.

This miracle was the last gift to Archimandrite Nicholas from the holy passion-bearers, who thanked him for his long and devoted service both during their lives and after their martyrdom.

Tatiana Manakova

The article uses photographs from the archives of Charles Gibbs and Maria Chuprinskaya

Despite many publications about the last years of the family of Emperor Nicholas II , there are many white spots left in this area. Very little has been written about the people who did not leave the royal family until the day of its tragic death. Among them is the Englishman Charles Sydney Gibbs, a man of complex and interesting fate.

Arriving in Russia as a young man, Gibbs evolved over the years from an inexperienced English teacher to a confidant of the family of Nicholas II.

The years spent with the imperial family had a tremendous impact on his entire life and worldview. Throughout his long life, he remained faithful to the memory of the royal family and managed to preserve many relics of great value for Russian history. Having gone through a difficult path to the Orthodox faith, Charles Gibbs made a significant contribution to the spread of Orthodoxy in Great Britain.

Charles Sidney Gibbs came to Russia in the spring of 1901 as an English teacher. Over time, he becomes a member and then president of the St. Petersburg Guild of English Teachers.

One day, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna was told that her daughters spoke English poorly (with a Scottish accent), and Gibbs was recommended to her. In the autumn of 1908, he arrived in Tsarskoe Selo and was introduced to his future students - the Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana, who were then 13 and 11 years old. Later, nine-year-old Anastasia joined the classes.

Many years later, Gibbs recalled: “The Grand Duchesses were very beautiful, cheerful girls, simple in their tastes and pleasant to talk to. They were quite intelligent and quick to understand when they could concentrate. However, each had her own special character and her own talents.”

Three years later, the Empress asked Gibbs to mentor the prince in teaching him English. Alexei was then eight years old. Before that, he would often come into class - "a tiny little kid in white tights and a shirt bordered with blue and silver Ukrainian embroidery." He used to come into class at 11 o'clock, look around and then seriously shake hands. But I didn’t know a word of Russian, and he was the only child in the family who had not had an English nanny since birth, and he didn’t know a single word of English. In silence we shook hands and he left.”

When Gibbs began working with Alexei, the boy was pale, nervous and weak due to an worsening illness. Several months passed until an atmosphere of mutual understanding and trust was achieved. Alexey felt more free and tried to speak more English.

It so happened that on the day of the king's abdication, Gibbs left the palace, going to the city to find out the news. However, he did not manage to return back immediately. The intervention of the British ambassador, who wrote a letter to the head of the Provisional Government asking him to allow Gibbs to return to the palace, did not help either. But there was no positive answer.

Gibbs began sending letters to the palace, in which he carefully reported news about the situation in the city. He was allowed to return to the palace only on August 2, 1917 - the day after the imperial family left him. Gibbs decided to follow the people who had become close to him.

Gibbs began sending letters to the palace, in which he carefully reported news about the situation in the city. He was allowed to return to the palace only on August 2, 1917 - the day after the imperial family left him. Gibbs decided to follow the people who had become close to him.

At the beginning of October he managed to reach Tobolsk. He barely managed to get on the last ship leaving Tyumen before the end of navigation. He also became the last of those who managed to obtain permission to join the royal family.

According to Gibbs' recollections, he was amazed to see how Alexandra Fedorovna had aged over the past five months. At the same time, Alexey looked healthier than usual.

Everyone greeted Gibbs with joy. He brought fresh, although not very encouraging, news, messages from friends and relatives, new books, and with his arrival it became much more fun to spend the long winter evenings. Gibbs continued his studies with the three younger princesses and Alexei. He then kept the two notebooks in which Maria and Anastasia wrote dictations throughout his life.

Before Christmas, the Empress asked Gibbs to write a letter on his behalf to Margaret Jackson, her former governess, to whom she was deeply attached and with whom she corresponded for many years, confiding her joys and sorrows. Now, with the help of this letter, the queen wanted to give the English side detailed information about the situation in Tobolsk, without revealing its true author and addressee. Gibbs's drafts preserve his attempts to convey the main points, masked by the style of private correspondence: “You must have read in the newspapers that many changes have taken place.

In August, the Provisional Government decided to move the residence from Tsarskoye Selo to Tobolsk.” Then comes a description of the city, the rooms in the governor’s house and the details of everyday life, and then: “You haven’t written for a hundred years, or maybe the letters haven’t arrived. Try writing again, and maybe the next one will reach the addressee. Write news about everyone: how "What are they doing? I heard that David returned from France, like his mother and father? And his cousins, are they at the front too? " David is the Prince of Wales, and Alexandra Feodorovna was sure that his name would tell Margaret what she needed deliver this letter to the queen.

But the answer never came. Later, Gibbs managed to find out that the letter sent from Tobolsk by diplomatic mail reached Petrograd, but there its trace was lost. There is no such letter in the English Royal Archives, although there are other references to Gibbs there.

In his memoirs, Gibbs writes about the day when the Emperor and Empress learned that they were being taken away from Tobolsk. Although they were not told where they were going, everyone thought it was to Moscow. “They said little... It was a solemn and tragic parting.” At dawn, all the servants gathered on the glassed-in veranda. “Nicholas shook everyone’s hand and said something to everyone, and we all kissed the Empress’s hand.”

To Ekaterinburg, Gibbs, Pierre Gilliard (a French teacher), Baroness Buxhoeveden, Mademoiselle Schneider and Countess Gendrikova traveled in a fourth-class carriage, which was not much different from a heated freight carriage.

To Ekaterinburg, Gibbs, Pierre Gilliard (a French teacher), Baroness Buxhoeveden, Mademoiselle Schneider and Countess Gendrikova traveled in a fourth-class carriage, which was not much different from a heated freight carriage.

The train stopped before reaching the station. Gibbs looked out of the window: several droshky stood on the embankment, waiting for passengers. He and Gilliard saw how the princesses, stuck in the mud, tried to climb onto a slippery embankment. Tatiana carried heavy suitcases in one hand, holding her small dog in the other.

Sailor Nagorny came up to help, but the guards rudely pushed him away. The droshky left and the train arrived at the station. General Tatishchev, Countess Gendrikova and Mademoiselle Schneider were taken away by guards and were never seen again.

At five in the evening, those remaining were told that they could go wherever they wished, but they were not allowed to be with the imperial family. In the end they decided to send them back to Tobolsk, but the advance of the White Army prevented these plans, and they were left in Yekaterinburg. They spent about ten days in the carriage. Every day they walked into the city, usually one or two at a time, so as not to attract attention, and passed by the Ipatiev House, hoping to catch a glimpse of someone from the royal family. One day, Gibbs saw a woman's hand opening a window and thought it might be Anna Demidova. Another day, Gibbs and Gilliard, walking near the house, saw the sailor Nagorny, who was being led by soldiers with bayonets. He noticed them too, but pretended not to recognize them. Four days later he was shot.

Gibbs and Gilliard were forced to leave for Tyumen, from where they regularly called the British consulate, trying to find out something new about the situation of the imprisoned family and about the rapidly advancing White Army, on which high hopes were placed.

On July 26, the Whites took Yekaterinburg. Having barely learned about this, Gibbs and Gilliard went there from Tyumen. In Ipatiev's house they saw terrible destruction. Everything spoke of a murder that had taken place here. But what then did the official statement of the Soviet government mean that the empress and heir were in a safe place? What about the daughters and servants who were not mentioned? Gilliard was inclined to hope for something, Gibbs was more skeptical.

In September he settles in Yekaterinburg, where he gives private lessons. Since he was known at the British Consulate, he was introduced to Charles Eliot, the British High Commissioner to Siberia.

Gibbs followed the investigation into the murder of the royal family, and he was always invited as one of those people who could identify the objects found. He copied the testimony of witnesses, even those who conveyed only rumors or secondary information.

At this time, the British High Commissioner offered him the post of secretary on his staff. Gibbs immediately agreed to this proposal - he was already very tired and missed his compatriots.

The British mobile headquarters was located in Omsk and was located in a large railway carriage, adapted for housing and work. Arriving in Omsk, Gibbs learned that the headquarters was leaving for Vladivostok.

On February 27, already in Vladivostok, Gibbs met with General Mikhail Dieterichs, with whom he worked during the first investigation in Yekaterinburg. Dieterichs told him that he had brought with him all the materials and things he had collected. He intended to send them to England. That same evening they met with the captain of the ship on which this valuable cargo was supposed to be sent. The items, including some rather bulky ones, such as the Empress's wheelchair, were described.

In the summer of 1919, Gibbs assisted investigator Sokolov in his investigation into the murder of the imperial family. He again visits the Ipatiev House, the mines where they looked for the bodies of the royal martyrs. In a letter to his aunt Kate, Gibbs talks about the touching and sad service in memory of members of the imperial family, which took place on July 17, 1919, the anniversary of their death.

Gibbs already really wanted to return to England. However, his future was unclear and alarming. At times he must have felt like a secret agent, as Dieterichs and Sokolov entrusted him with information they both considered dangerous and material evidence they believed posed a threat.

Sokolov and Dieterichs met with Gibbs again in Chita on Christmas Day, January 7, 1920. They said their lives were in danger because they had information about the killers. Dieterichs brought with him a small box covered with dark lilac leather that had previously belonged to the empress. "I want you to take this box with you now. It contains all their remains," he told Gibbs.

The British mission went to Harbin. Dieterichs handed some of the things to the head of the mission, Lampson, assuming that he would hand them over to Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich or General Denikin. However, from Harbin, Lampson and some of his employees, including Gibbs, were sent to Beijing. From there, in February 1930, Lapson made a report to London and asked that the materials be taken into custody. A negative answer came in March. At this time, Sokolov and Dieterichs were also in Beijing. They managed to meet with the French general Yanin and ask him for help. Yanin said that “he considers the fulfillment of the mission that we entrusted to him as a fulfillment of a duty of honor to a faithful ally.” According to some reports, the box given to the general is still kept in his family.

Shortly afterwards the British Mission to Siberia ceased to exist and Gibbs' service ended. It seemed that he was now free to return to England, but his mood changed. He remembered how painfully Nicholas II perceived the British reaction to his abdication, the joy of the British Parliament and the congratulatory telegram to the Provisional Government. Gibbs's home country did not provide refuge to the imperial family. And he didn't want to go back there.

Gibbs spent seven years in Harbin. In 1924, he began to receive letters in which he was asked if he knew about the surviving members of the royal family. A London law firm asked him to identify the woman in the photograph. Gibbs sent a cautious reply: the woman bore some resemblance to Grand Duchess Tatiana, although the eyes - the most memorable part of Tatiana's face - were darkened in the photograph, and the woman's hands seemed too large and wide. Friends and relatives of the Romanovs began to bombard him with articles that talked about the grand duchesses who allegedly escaped death, and demanded to comment on this, but Gibbs preferred to remain silent.

Despite his then renewed interest in Buddhism, Gibbs often attended the Russian church, and his friends included priests and parishioners who had special respect for him because of his connections to the royal family. Gibbs made a pilgrimage to Beijing, where he visited the shrine with the relics of members of the imperial family, buried there after General Dieterichs, risking his own life, brought them from Siberia and entrusted them to the Russian Orthodox Mission. The coffins were placed in the crypt of the cemetery church that belonged to the mission. Even before Gibbs's visit, the relics of Grand Duchess Elizabeth and nun Barbara were transported to Jerusalem for burial in the Church of St. Mary Magdalene, where the Venerable Martyr Elizabeth wished to be buried.

Having made this pilgrimage to Beijing, Gibbs decides to return to England. His family greeted him as joyfully as if he had risen from the dead.

In September 1928, he entered a pastoral course at Oxford and began to carefully study the works of the holy fathers. At that time, there was a debate in England about simplifying church language, which caused serious damage to the authority of the Church. Gibbs understands that he will not serve in the Anglican Church. Continuing to be registered with the customs department, Gibbs was forced to return to Harbin in October 1929. However, in mid-September 1931, hostilities began between the Chinese nationalists and the Japanese army based in Mukden. In 1932, Japan captured Manchuria, and Gibbs was left without a job.

According to some reports, he spent one year in a Japanese Buddhist monastery, but this did not relieve him of his feelings of disappointment and spiritual emptiness.

He increasingly remembered the spiritual strength that helped the members of the royal family maintain courage and dignity in the midst of all the terrible trials that befell them. Gibbs remembered a poetic prayer composed by Countess Gendrikova. The family often read this prayer together:

Send us, Lord, patience

In a time of violent dark days

To endure popular persecution

And the torture of our executioners.

Give us strength, O righteous God,

Forgiving one's neighbor's crime

And the cross is heavy and bloody

To meet with Your meekness.

And in the days of rebellious excitement,

When our enemies rob us,

To endure shame and insults,

Christ the Savior, help.

Lord of the world, God of the universe,

Bless us with your prayer

And give rest to the humble soul

At an unbearably terrible hour.

And at the threshold of the grave

Breathe into the mouths of your slaves

Superhuman powers

Pray meekly for your enemies.

Gibbs was close to a great secret that he was only now able to recognize. He hurriedly goes to Harbin to become Orthodox. At baptism, Gibbs took the name Alexy - in honor of the prince.

Gibbs's spiritual father was Archbishop Nestor of Kamchatka and Peter and Paul. He was a missionary who brought the light of the Gospel to the pagan Kamchadals. He came to Harbin in 1921, fleeing the Red Terror. And here he also showed his energy and experience, organizing canteens for the poor, orphanages and hospitals for the emigrant community.

Gibbs tried to express his feelings in one of his letters to his sister: it was “almost like returning home after a long journey.”

In December 1935, Gibbs became a monk. In monasticism he was given the name Nikolai. That same year he became a deacon and then a priest. All this time, he discussed with his mentor Archbishop Nestor the possibility of creating an Orthodox monastery in England. The Archbishop blessed him to go to the Russian Orthodox Mission in Jerusalem for one year to get to know monastic life better.

The Jerusalem Mission was founded at the end of the 19th century to provide assistance to Russian pilgrims, who at that time were arriving in the Holy Land in large numbers. After 1917, the flow of pilgrims from Russia dried up, but monks and nuns remained in the Mission. The remains of Grand Duchess Elizabeth and nun Varvara were buried here.

In 1937, Hieromonk Nicholas (Gibbs) returned to England. However, he fails to found a monastic community there. In 1938, Archbishop Nestor, who was touring Europe, visited London. He ordains Father Nicholas as an archimandrite and places a miter on him.

In 1937, Hieromonk Nicholas (Gibbs) returned to England. However, he fails to found a monastic community there. In 1938, Archbishop Nestor, who was touring Europe, visited London. He ordains Father Nicholas as an archimandrite and places a miter on him.

In 1941, Father Nikolai was invited to Oxford to organize a parish there. Many emigrants - translators, journalists, scientists - came to this university town. Services were held in an ancient cathedral located on the territory of one of the colleges. After the end of the war, students returned to college, and Father Nicholas began searching for a permanent location for the church. He found three suitable cottages and invested most of his savings into their purchase. In 1946, a temple in honor of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker was consecrated in one of these buildings.

When the troubles associated with the repairs were over, Father Nikolai took out an amazing collection of things related to the imperial family that he had kept for almost 30 years. Most of these things were taken from Ipatiev's house in 1918 with the permission of General Dieterichs.

He hung icons on the walls of the temple, some of which were given to him by members of the imperial family, and some of which he saved from the Ipatiev House. In the center of the temple, Father Nikolai hung a chandelier in the form of pink lilies with metallic green leaves and a branch of violets. This chandelier used to hang in the bedroom in the Ipatiev House.

In the altar, Father Nicholas placed boots that belonged to Nicholas II, which he captured from Tobolsk to Yekaterinburg, believing that the Tsar might need them, but he was no longer destined to see the Tsar.

And at every service he remembered the emperor, empress, prince and grand duchesses.

Father Nikolai hoped to found a museum using the things he had and then attract other people who kept the memory of the royal family, as well as open a Russian cultural center in London. But lack of funds did not allow him to do this.

However, he converted the library room into a miniature museum. Here he placed photographs that he took in Tsarskoe Selo, Tobolsk and Yekaterinburg; study books for Maria and Anastasia; several menu sheets from Tobolsk with images of the imperial cross; a pencil case that belonged to the prince and a bell with which he played; a copper coat of arms from the imperial yacht "Standart" and many other things that he saved.

In 1941, when Gibbs arrived in London, he was already 65 years old and needed an assistant. A few years later, he talks about his situation in a letter to Baroness Buxhoeveden: “It is already four years since I invited the son of Stolypin’s Minister of Agriculture (Krivoshein) to come to me from Holy Mount Athos, where he spent 25 years as a monk after completing his studies at the Sorbonne. .. Father Vasily is now a scientist with a fairly high name... In the second year of his arrival, I organized everything for his ordination to the priesthood... Then he took upon himself all the responsibilities associated with the temple.”

In 1945, Father Nikolai moved to the Moscow Patriarchate. And he was left in painful loneliness. In 1959, the Russian Parish Council decided to move to the House of St. Basil and St. Macrina, founded by Nikolai Zernov. Father Vasily (Krivoshein), who later became archbishop, also moved. Father Nikolai was deeply offended, believing that this would lead to the disintegration of the parish.

However, even in the last years of his life, Father Nikolai was surrounded by friends. A year before his death, Father Nikolai lost a lot of weight and was quickly losing strength. But his face was amazing... Very pink cheeks, bright blue eyes and a scraggly snow-white beard that reached the middle of his chest. He was an interesting and witty conversationalist, his mind was clear. It amazed with its simplicity and practicality at the same time. Despite his difficult life and unusual appearance, he was a perfect Englishman in his practical approach to things and in his sense of humor... He had a natural authority, he was a man who was admired and not argued with.

Father Nicholas died on 24 March 1963, aged 87, and was buried in Headington Cemetery, Oxford. As his friends who visited him in these last months said, despite his weakness, he always smiled.

After his death, David Beatti and another friend of Nikolai's father went to his London apartment to find out whether Father Nikolai's archive and things were in danger of being sold off. They were assured that this would not happen, and were invited to the bedroom of Father Nicholas, where an icon hung above the bed - one of those that had once been given to him by the imperial family. Over the years, its colors have faded and faded. But three days before the death of Father Nikolai, the colors gradually began to renew themselves and became bright as before.

And it was like a gift to Father Nicholas from the holy royal martyrs, to thank him for his long and devoted service, both during their lives and after their martyrdom.