Tsarevich Alexey. Fatal love for a serf spy. State criminal or victim of intrigue: why Peter I condemned his son to death What happened to the son of Peter 1 Alexei

According to official records kept in the archives of the Secret Chancellery of Sovereign Peter I, on June 26 (July 7), 1718, in a cell of the Peter and Paul Fortress, a previously convicted state criminal, Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich Romanov, died of a stroke (cerebral hemorrhage). This version of the death of the heir to the throne raises great doubts among historians and makes them think about his murder, committed on the orders of the king.

Childhood of the heir to the throne

Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich, who by right of birth was supposed to succeed his father, Tsar Peter I, on the Russian throne, was born on February 18 (28), 1690 in the village of Preobrazhenskoye near Moscow, where the royal summer residence was located. It was founded by his grandfather - Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, who died in 1676, in whose honor the young heir to the crown received his name. From then on, Saint Alexis, the man of God, became his heavenly patron. The Tsarevich’s mother was the first wife of Peter I, Evdokia Fedorovna (née Lopukhina), who was imprisoned by him in a monastery in 1698 and, according to legend, cursed the entire Romanov family.

In the early years of his life, Alexei Petrovich lived in the care of his grandmother, Dowager Tsarina Natalya Kirillovna (née Naryshkina), the second wife of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. According to contemporaries, even then he was distinguished by a hot-tempered disposition, which is why, having begun to learn to read and write at the age of six, he often beat his mentor, the petty nobleman Nikifor Vyazemsky. He also loved to pull the beard of the confessor assigned to him, Yakov Ignatiev, a deeply pious and pious man.

In 1698, after his wife was imprisoned in the Suzdal-Pokrovsky Monastery, Peter transferred his son to the care of his beloved sister, Natalya Alekseevna. And before, the sovereign had little interest in the details of Alyosha’s life, but from then on he stopped worrying about him altogether, limiting himself only to sending his son new teachers twice in a short time, whom he selected from among highly educated foreigners.

Difficult child

However, no matter how hard the teachers tried to instill the European spirit in the young man, all their efforts were in vain. According to Vyazemsky’s denunciation, which he sent to the Tsar in 1708, Alexei Petrovich tried in every possible way to evade the activities prescribed to him, preferring to communicate with various kinds of “priests and monks-monks,” among whom he often indulged in drunkenness. The time spent with them contributed to the rooting of hypocrisy and hypocrisy in him, which had a detrimental effect on the formation of the young man’s character.

In order to eradicate these extremely undesirable inclinations in his son and introduce him to the real business, the tsar instructed him to supervise the training of recruits recruited in connection with the advance of the Swedes deep into Russia. However, the results of his activities were extremely insignificant, and, worst of all, he went without permission to the Suzdal-Pokrovsky Monastery, where he met his mother. With this rash act, the prince incurred the wrath of his father.

Brief married life

In 1707, when Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich turned 17 years old, the question arose about his marriage. From among the contenders for marriage with the heir to the throne, the 13-year-old Austrian princess Charlotte of Wolfenbüttel was chosen, who was very cleverly matched to the future groom by his teacher and tutor, Baron Hussein. Marriage between members of the reigning families is a purely political issue, so they were in no particular hurry with it, carefully considering all the possible consequences of this step. As a result, the wedding, which was celebrated with extraordinary pomp, took place only in October 1711.

Three years after marriage, his wife gave birth to a girl, Natalya, and after some time a boy. This only son of Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich, named after his crowned grandfather, eventually ascended to the Russian throne and became Tsar Peter II. However, soon a misfortune happened - as a result of complications that arose during childbirth, Charlotte unexpectedly died. The widowed prince never married again, and he was consoled as best he could by the young beauty Euphrosyne, a serf maiden given to him by Vyazemsky.

Son rejected by father

From the biography of Alexei Petrovich it is known that further events took an extremely unfavorable turn for him. The fact is that in 1705, his father’s second wife, Catherine, gave birth to a child who turned out to be a boy and, therefore, the heir to the throne, in the event that Alexei abandoned him. In this situation, the sovereign, who had previously not loved the son born of a woman whom he treacherously hid in a monastery, became imbued with hatred towards him.

This feeling, raging in the tsar’s chest, was largely fueled by anger caused by Alexei Petrovich’s reluctance to share with him the work of Europeanizing patriarchal Russia, and by the desire to leave the throne to the new contender who had barely been born - Pyotr Petrovich. As you know, fate opposed this wish of his, and the child died at an early age.

In order to stop all attempts by his eldest son to claim the crown in the future, and to remove himself out of sight, Peter I decided to follow the path already trodden by him and force him to become a monk, as he once did with his mother. Subsequently, the conflict between Alexei Petrovich and Peter I became even more acute, forcing the young man to take the most drastic measures.

Flight from Russia

In March 1716, when the sovereign was in Denmark, the prince also went abroad, allegedly wanting to meet his father in Copenhagen and inform him of his decision regarding monastic tonsure. Voivode Vasily Petrovich Kikin, who then held the position of head of the St. Petersburg Admiralty, helped him cross the border, contrary to the royal ban. He subsequently paid for this service with his life.

Finding himself outside of Russia, the heir to the throne Alexei Petrovich, the son of Peter I, unexpectedly for the retinue accompanying him, changed his route, and, bypassing Gdansk, went straight to Vienna, where he then conducted separate negotiations both with the Austrian Emperor Charles himself and with the whole a number of other European rulers. This desperate step, which the prince was forced to take by circumstances, was nothing more than high treason, but he had no other choice.

Far-reaching plans

As is clear from the materials of the investigation, in which the fugitive prince became a defendant some time later, he planned, having settled on the territory of the Holy Roman Empire, to wait for the death of his father, who, according to rumors, was seriously ill at that time and could die at any moment. After this, he hoped, with the help of the same Emperor Charles, to ascend to the Russian throne, resorting, if necessary, to the help of the Austrian army.

In Vienna they reacted very sympathetically to his plans, believing that Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich, the son of Peter I, would be an obedient puppet in their hands, but they did not dare to openly intervene, considering it too risky an undertaking. They sent the conspirator himself to Naples, where, under the skies of Italy, he had to hide from the all-seeing eye of the Secret Chancellery and monitor the further development of events.

Historians have at their disposal a very interesting document - a report from the Austrian diplomat Count Schoenberg, which he sent to Emperor Charles in 1715. It states, among other things, that the Russian Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich Romanov has neither the intelligence, nor the energy, nor the courage necessary for decisive action aimed at seizing power. Based on this, the count considered it inappropriate to provide him with any assistance. It is possible that it was this message that saved Russia from another foreign invasion.

Homecoming

Having learned about the flight of his son abroad and foreseeing the possible consequences, Peter I took the most decisive measures to capture him. He entrusted direct leadership of the operation to the Russian ambassador to the Viennese court, Count A.P. Veselovsky, but he, as it turned out later, assisted the prince, hoping that when he came to power he would reward him for the services rendered. This miscalculation brought him to the chopping block.

Nevertheless, agents of the Secret Chancellery very soon established the location of the fugitive hiding in Naples. The Holy Roman Emperor responded to their request for the extradition of a state criminal with a decisive refusal, but allowed the royal envoys - Alexander Rumyantsev and Peter Tolstoy - to meet with him. Taking advantage of the opportunity, the nobles handed the prince a letter in which his father guaranteed him forgiveness of guilt and personal safety in the event of a voluntary return to his homeland.

As subsequent events showed, this letter was just an insidious trick aimed at luring the fugitive to Russia and dealing with him there. Anticipating such an outcome of events and no longer hoping for help from Austria, the prince tried to win over the Swedish king to his side, but never received an answer to the letter sent to him. As a result, after a series of persuasion, intimidation and all sorts of promises, the fugitive heir to the Russian throne, Alexei Petrovich Romanov, agreed to return to his homeland.

Under the yoke of accusations

Repression fell on the prince as soon as he arrived in Moscow. It began with the fact that on February 3 (14), 1718, the sovereign’s manifesto was published depriving him of all rights of succession to the throne. In addition, as if wanting to enjoy the humiliation of his own son, Peter I forced him within the walls of the Assumption Cathedral to publicly swear an oath that he would never again lay claim to the crown and would renounce it in favor of his half-brother, the young Peter Petrovich. At the same time, the sovereign again committed an obvious deception, promising Alexei, subject to a voluntary admission of guilt, complete forgiveness.

Literally the next day after the oath taken in the Assumption Cathedral of the Kremlin, the head of the Secret Chancellery, Count Tolstoy, began an investigation. His goal was to clarify all the circumstances related to the treason committed by the prince. From the records of the inquiry it is clear that during interrogations, Alexey Petrovich, showing cowardice, tried to shift the blame to the closest dignitaries, who allegedly forced him to enter into separate negotiations with the rulers of foreign states.

Everyone he pointed out was immediately executed, but this did not help him avoid answering. The defendant was exposed by many irrefutable evidence of guilt, among which the testimony of his mistress, the same serf maiden Euphrosyne, generously given to him by Vyazemsky, turned out to be especially disastrous.

Death sentence

The Emperor closely followed the progress of the investigation, and sometimes he himself conducted the investigation, which formed the basis of the plot of the famous painting by N. N. Ge, in which Tsar Peter interrogates Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich in Peterhof. Historians note that at this stage the defendants were not handed over to executioners and their testimony was considered voluntary. However, there is a possibility that the former heir slandered himself out of fear of possible torment, and the girl Euphrosyne was simply bribed.

One way or another, by the end of the spring of 1718, the investigation had sufficient materials to accuse Alexei Petrovich of treason, and the trial that took place soon sentenced him to death. It is known that at the meetings his attempt to seek help from Sweden, a state with which Russia was then at war, was not mentioned, and the decision was made on the basis of the remaining episodes of the case. According to contemporaries, upon hearing the verdict, the prince was horrified and on his knees begged his father to forgive him, promising to immediately become a monk.

The defendant spent the entire previous period of time in one of the casemates of the Peter and Paul Fortress, ironically becoming the first prisoner of the notorious political prison into which the citadel founded by his father gradually turned. Thus, the building with which the history of St. Petersburg began is forever associated with the name of Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich (a photo of the fortress is presented in the article).

Various versions of the death of the prince

Now let's turn to the official version of the death of this unfortunate scion of the House of Romanov. As mentioned above, the cause of death that occurred even before the sentence was carried out was called a blow, that is, hemorrhage in the brain. Perhaps in court circles they believed this, but modern researchers have great doubts about this version.

First of all, in the second half of the 19th century, Russian historian N. G. Ustryalov published documents according to which, after the verdict, Tsarevich Alexei was subjected to terrible torture, apparently wanting to find out some additional circumstances of the case. It is possible that the executioner was overzealous and his actions caused his unexpected death.

In addition, there is evidence from persons involved in the investigation who claimed that while in the fortress, the prince was secretly killed on the orders of his father, who did not want to compromise the Romanov family name with a public execution. This option is quite probable, but the fact is that their testimony is extremely contradictory in detail, and therefore cannot be taken on faith.

By the way, at the end of the 19th century, a letter allegedly written by a direct participant in those events, Count A.I. Rumyantsev, and addressed to a prominent statesman of the Peter the Great era, V.N. Tatishchev, became widely known in Russia. In it, the author talks in detail about the violent death of the prince at the hands of jailers who carried out the order of the sovereign. However, after proper examination, it was determined that this document was a fake.

And finally, there is another version of what happened. According to some information, Tsarevich Alexei suffered from tuberculosis for a long time. It is possible that the experiences caused by the trial and the death sentence imposed on him provoked a sharp exacerbation of the disease, which became the cause of his sudden death. However, this version of what happened is not supported by convincing evidence.

Disgrace and subsequent rehabilitation

Alexei was buried in the cathedral of the very Peter and Paul Fortress, of which he happened to be the first prisoner. Tsar Peter Alekseevich was personally present at the burial, wanting to make sure that the body of his hated son was swallowed up by the earth. He soon issued several manifestos condemning the deceased, and Novgorod Archbishop Feofan (Prokopovich) wrote an appeal to all Russians, in which he justified the tsar’s actions.

The name of the disgraced prince was consigned to oblivion and was not mentioned until 1727, when, by the will of fate, his son ascended to the Russian throne and became Emperor of Russia, Peter II. Having come to power, this young man (he was barely 12 years old at the time) completely rehabilitated his father, ordering that all articles and manifestos compromising him be withdrawn from circulation. As for the work of Archbishop Feofan, published at one time under the title “The Truth of the Will of the Monarchs,” it, too, was declared to be malicious sedition.

Real events through the eyes of artists

The image of Tsarevich Alexei is reflected in the works of many Russian artists. It is enough to recall the names of the writers - D. S. Merezhkovsky, D. L. Mordovtsev, A. N. Tolstoy, as well as the artist N. N. Ge, who was already mentioned above. He created a portrait of Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich, full of drama and historical truth. But one of his most striking incarnations was the role played by Nikolai Cherkasov in the film “Peter the First,” directed by the outstanding Soviet director V. M. Petrov.

In it, this historical character appears as a symbol of the bygone century and the deeply conservative forces that prevented the implementation of progressive reforms, as well as the danger posed by foreign powers. This interpretation of the image was fully consistent with official Soviet historiography; his death was presented as an act of just retribution.

Peter and Paul Fortress, the place of the famous ghost of Princess Tarakanova (see my post, who found herself a prisoner of these gloomy walls due to the betrayal of her loved one. It is a sad coincidence that another eminent prisoner of Peter and Paul Fortress, Tsarevich Alexei, son of Peter I, found himself in similar trouble at the beginning of the 18th century. Love also played a fatal role in the arrest and death of the prince. Alexei was betrayed by his favorite Afrosinya Fedorova (Efrosinya), a serf girl whom he was ready to marry.

Peter and Paul Fortress, where Tsarevich Alexei died. They say his sad ghost haunts there. Afrosinya's shadow is also doomed to wander there and look for the prince to ask for forgiveness... This is the only way they will find peace. Nobody knows how to help restless souls.

Tsarevich Alexei is often credited with all sorts of obscurantism, and the same qualities will be given to his companion. "A serf is a working girl." However, judging by her letters, Afrosinya belonged to that category of serfs who studied “together with the young ladies in various sciences” and became companions of their masters.

Afrosinya became the companion of Tsarevich Alexei and accompanied him everywhere in the costume of a page; the Tsarevich traveled with her throughout Europe. Chancellor Schönborn called the Tsarvich's companion "petite page" (little page), mentioning her miniature physique. In Italy, pageboy costumes were made from colored velvet fabric, which the ladies really liked, and every fashionista had such a men's outfit in her wardrobe. Quite in the style of the gallant century, but the romantic story of the prince ended tragically.

Tsar Peter was not sad about his son’s passion, since he himself “married a washerwoman,” as his fellow monarchs grumbled.

The favorite proved herself to be a “faithful friend” of the prince, and her sudden testimony against Alexei causes bewilderment among researchers. According to one version, she was intimidated - Afrosinya and Alexey had a young son at the party. Another version is sadder - Afrosinya was a secret agent of Count Tolstoy, who promised the girl a rich reward and long-awaited freedom for a successful mission. This is the basis for Afrosinya’s brilliant education and confident journey through Europe with Alexey. Tolstoy, as the head of the Secret Chancellery, prepared Afrosinya in advance.

Ceremonial portrait of the prince

In their correspondence, the prince and Afrosinya discuss opera, which fully indicates education.

“But I didn’t catch any opera or comedy, just one day I went on a gondola to church with Pyotr Ivanovich and Ivan Fedorovich to listen to music, I didn’t go anywhere else...”

The prince answers Afrosinya:

“Ride in a letig*, slowly, because in the Tyrolean mountains the road is rocky: you yourself know; and where you want, rest for as many days as you want.”

*letiga – carriage

Letter from Afrosinya

The favorite clearly reported to the prince about her expenses: “I am informing you about my purchases, which, while in Venice, I bought: 13 cubits of gold cloth, 167 ducats were given for this cloth, and a cross made of stones, earrings, a lavender ring, and 75 ducats were given for this headdress...”

Contrary to stereotypes, Tsarevich Alexei did not hate Europe, but he loved Italy and the Czech Republic and would not refuse to settle in these fertile lands away from his father’s turbulent politics. Alexey spoke and wrote fluent German.

Historian Pogodin notes “The Tsarevich was inquisitive: from his handwritten travel expenses book we see that in all the cities where he stopped, he bought almost first of all books and for significant sums. These books were not only of spiritual content, but also historical, literary, maps, portraits, I saw the sights everywhere.”

Contemporary Huysen wrote about the prince: “He has ambition, tempered by prudence, common sense, a great desire to distinguish himself and acquire everything that is considered necessary for the heir of a large state; He is of a compliant and quiet disposition and shows a desire to replenish with great diligence what was missed in his upbringing.”

The prince had disagreements with his father for political reasons. Peter called Alexei to arms, and the prince was a supporter of peaceful life; he was more interested in the well-being of his own estates. Alexey was not ready for war and intrigue, but he should not be classified as a stupid obscurantist either. Usually history is written by the winner, making the losers look bad. This happened later with Peter III and Paul I.

Researchers explain Alexey’s disagreements with his father:

“For 13 years (from 9 to 20 years of the prince’s life), the tsar saw his son no more than 5-7 times and almost always addressed him with a severe reprimand.”

“The caution, secrecy, and fear visible in Alexei’s letters testify not only to the cold, but even hostile relationship between the son and his father. In one letter, the prince calls it a prosperous time when his father leaves.”

After listening to those close to him, Peter became worried that the prince might find allies in Europe and try to get the crown without waiting for his father’s natural death. Peter ordered Count Tolstoy to return his son to Russia.

Presumably, Tolstoy ordered his agent, Afrosinya, to influence the decision of Alexei, who agreed to carry out his father’s will.

“My gentlemen! I received your letter, and that my son, trusting my forgiveness, really already went with you, which made me very happy. Why do you write that he wants to marry the one who is with him, and he will be very much allowed to do so when he comes to our region, even in Riga, or in his own cities, or in Courland at his niece’s house, but to marry in foreign lands , it will bring more shame. If he doubts that he will not be allowed, he can judge: when did I absolve him of such a great guilt, and why should I not allow him this small matter? I wrote about this in advance and reassured him about it, which I still confirm today. Also, to live wherever he wants, in his villages, in which you firmly reassure him with my word.”- wrote Peter I, giving Alexei’s consent to marry a serf.

Alexey abdicated the throne, wanting a quiet life on his estate:

“Father took me to eat with him and acts kindly towards me! God grant that this will continue in the same way, and that I may wait for you in joy. Thank God that we were excommunicated from the inheritance, so that we can remain in peace with you. God grant that we live happily with you in the village, since you and I wanted nothing more than to live in Rozhdestvenka; You yourself know that I don’t want anything, just to live with you until death.”- he wrote to Afrosinya.

To which Vasily Dolgoruky said: “What a fool! He believed that his father promised him to marry Afrosinya! Pity him, not marriage! Damn him: everyone is deceiving him on purpose!”

Dolgoruky paid for such chatter; the spies reported everything to Peter.

Princess Charlotte, Alexei's legal wife. Their marriage lasted 4 years. Dynastic ties without reciprocity brought suffering to both. Charlotte died at the age of 21. “I am nothing more than a poor victim of my family, who did not bring her the slightest benefit, and I am dying a slow death under the burden of grief.”- Charlotte wrote down.

“He took a certain idle and hard-working girl and lived with her clearly lawlessly, leaving his lawful wife, who then soon passed away her life, albeit from illness, but not without the opinion that the contrition from his dishonest life with her was a lot to that helped"- Alexey was condemned.

Pyotr Alekseevich - son of Charlotte and Alexei (future Peter II)

Peter refused to believe in his son’s conspiracy; he suspected that it was all to blame for troublemakers like Kikin, an embezzler, and his comrades who wanted to fly higher (see my post. The traitors wanted to overthrow their tsar-benefactor, to overthrow him, so that they could then rule in the name of Alexei, removing him from affairs of state. The tsar also suspected his first wife Evdokia of the conspiracy, who did not accept his policies and was exiled to a monastery.

“If it weren’t for the nun (Peter’s first wife), the monk (Bishop Dosifei) and Kikin, Alexey would not have dared to commit such unheard-of evil. Oh, bearded men! The root of much evil is old women and priests; my father dealt with one bearded man (Patriarch Nikon), and I dealt with thousands.”- said Peter.

The testimony of Afrosinya, who was under arrest in the Peter and Paul Fortress, decided the fate of the prince:

“The prince wrote letters in Russian to the bishops and in German to Vienna, complaining about his father. The prince said that there was a riot in the Russian troops and that this made him very happy. I rejoiced every time I heard about the unrest in Russia. Having learned that the younger prince was sick, he thanked God for this mercy towards him, Alexei. He said that he would transfer all the “old” ones and elect the “new” ones of his own free will. That when he becomes a sovereign, he will live in Moscow, and will leave Petersburg as a simple city, will not keep ships at all, and will have an army only for defense, because he does not want war with anyone. He dreamed that maybe his father would die, then there would be great turmoil, because some would stand for Alexei, and others would stand for Petrusha the Bigwig, and his stepmother was too stupid to cope with the turmoil...”

Afrosinya during interrogation in prison (Ekaterina Kulakova, film "Tsarevich Alexei")

“But he, the prince, used to say: when he becomes a sovereign, then he will live in Moscow, and Piterburkh will leave a simple city; He will also leave the ships and will not keep them; and he would keep the troops only for defense, and did not want to have a war with anyone, but wanted to be content with the old possession, and intended to live the winter in Moscow and the summer in Yaroslavl; and when I heard about some visions or read in the chimes that it was quiet and calm in St. Petersburg, I used to say that the vision and silence were not without reason.”

“Perhaps either my father will die, or there will be a rebellion: my father, I don’t know why, doesn’t love me, and wants to make my brother heir, he is still a baby, and my father hopes that his wife, and my stepmother, is smart ; and when, having done this, he dies, then there will be a woman’s kingdom. And there will be no good, but there will be confusion: some will stand for their brother, and others will stand for me... When I become king, I will transfer all the old ones, and recruit new ones for myself according to my own will..."

Alexey was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress, where, under pain of torture, he confirmed the testimony of his favorite. The youngest son of Peter I, to whom the Tsar wanted to bequeath the throne, recently died. The tragedy in the family made Peter especially suspicious of political treason.

Peter placed the fate of his son in the hands of the judges: “ I ask you, so that they truly carry out justice, which is worthy, without flattering me (from the French flatter - to flatter, to please.) and without fearing that if this matter is worthy of a light punishment, and when you inflict condemnation in such a way that I would be disgusted, in Therefore, do not be afraid at all: also do not reason that this judgment should be inflicted on you, as your sovereign, son; but regardless of face, do the truth and do not destroy your souls and mine, so that our consciences remain pure and the fatherland is comfortable.”

Judges - 127 people sentenced the prince to death, which was not carried out.

The Tsarevich died in the prison of the Peter and Paul Fortress on June 26 (July 7), 1718 at the age of 28. The exact circumstances of the death are unknown. For one reason, he was “in poor health,” for another, his own father ordered him to be killed, fearing a conspiracy; another version is that Count Tolstoy’s agents again tried to prevent the reconciliation of son and father.

According to historian Golikov: “The tears of this great parent (Peter) and his contrition prove that he had no intention of executing his son and that the investigation and trial carried out on him were used as a necessary means solely so that, by showing him the one to which he brought himself, to create in him a fear of continuing to follow the same erroneous paths.”

The French philosopher Voltaire wrote:

“People shrug their shoulders when they hear that the 23-year-old prince died of a stroke while reading a verdict that he should have hoped to have overturned.”(the philosopher was mistaken about Alexei’s age).

A.S. Pushkin believed that the prince was poisoned " 25 (June 1718) the ruling and sentence of the prince were read in the Senate... 26 the prince died poisoned.”

After the death of his son, Peter issued a decree: “Everyone knows how arrogant our son Alexei was by Absalom’s anger, and that it was not through his repentance that this intention, but by the grace of God, was stopped for our entire fatherland, and this grew out for nothing else, except from the old custom that the greatest son was given an inheritance, Moreover, at that time he was the only male of our surname, and for this reason he did not want to look at any fatherly punishment. ... Why did they decide to make this charter, so that it would always be in the will of the ruling sovereign, whoever he wants, to determine the inheritance, and to a certain one, seeing what obscenity, to repeal it, so that the children and descendants do not fall into such anger as is written , having this bridle on you. For this reason, we command that all our faithful subjects, spiritual and temporal, without exception, confirm this charter of ours before God and His Gospel on such a basis that anyone who is contrary to this, or interprets it in any other way, is considered a traitor, subject to the death penalty. and will be subject to a church oath. Peter".

After Alexei’s sad ending, Afrosinya was acquitted and received the long-awaited freedom “wherever she wants to go”:

“Give the girl Afrosinya to the commandant’s house, and let her live with him, and let her go with his people wherever she wants to go.”

Afrosinya also received a generous reward from the Secret Chancellery “To the girl Afrosinya, as a dowry, give her sovereign’s salary as an order of three thousand rubles from the money taken, blessed to the memory of Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich.”

To compare the scale of the award, in Peter’s era the maintenance of an infantryman cost the treasury - 28 rubles. 40 kopecks per year, and one dragoon - 40 rubles. 17 kopecks

Not everyone received such a “salary” from Peter’s secret service.

The further fate of Afrosinya Fedorova is unknown. It is believed that she and her son went abroad. They said that she did not expect that her testimony would lead to the death of Tsarevich Alexei... She believed Count Tolstoy that Alexei would only face exile - and she and her son would go with him. Until the end of her life, Afrosinya was haunted by the shadow of a man for whom she was a “dear friend,” and whom she betrayed... Freedom and money became the traitor’s “silver coins.” The plot for a novel from the times of the gallant age.

The stories of the gallant age did not always have a happy ending, alas...

Song about Tsarevich Alexei

Don't croak, crows, but above the clear falcon,

Don't laugh, people, at the daring fellow,

Over the daring fellow and over Alexei Petrovich.

And the gusli, you gusli!

Don't win, Guselians, well done to annoy you!

When I, a fine fellow, had a good time,

My dear sir loved me, my mother cherished me, they want to execute Tsarevich Alexei

And now she refused, the royal birth has gone crazy,

That they rang the bell, the bell is sad:

At the white oak block the executioners were all frightened,

Everyone ran away in the Senate...

One Vanka Ignashenok the thief,

He, the barbarian, was not afraid, he was not afraid.

He stands on the heels of the deaf woman and the cart,

In the middle of nowhere, in a cart, a daring, good fellow

Alexey Petrovich-light...

He sits without a cross and without a belt,

The head is tied with a scarf...

They brought the cart to the field on Kulikovo,

To the steppe and to Potashkina, to the white oak block.

Alexey Petrovich sends a petition

To my dear uncle, to Mikita Romanovich.

It didn’t happen to him at home, he wasn’t in the mansion,

He went into the soap bar and into the parsha

Yes, wash, and take a steam bath.

Petitioners come to their dear uncle

In the soapy warmth of the bathhouse.

He didn’t wash or take a steam bath,

He puts a broom on the silks

On an oak bench,

Puts down Kostroma soap

On the squinting window,

He takes the gold keys,

He goes to the white stone stable,

He has a good horse,

He saddles and saddles from Cherkassy,

And he galloped to the white oak block,

To my dear nephew Alexey and Petrovich,

He turned his nephew

From execution from hanging.

He comes to his white-stone chambers,

He started a party and a merry party.

And his dear father,

Peter, yes, the First,

There is sadness and sadness in the house,

The windows are hung with black velvet.

He calls and demands

Dear son-in-law and Mikita Romanovich:

“What, dear son-in-law, are you drinking in joy, tipsy,

And I’m feeling sad and sad:

My dear son Alexei and Petrovich is missing.”

Nikita Romanovich answers: “I’m drinking tipsy, out of joy, My dear one is visiting me.”

nephew Alexey and Petrovich...”

The Tsar-Sovereign was very happy about this,

He ordered his casement windows to be opened for light, for white people, and to be hung up.

scarlet velvet.

Tsarevich Alexei was born in February 1690 from the first marriage of Peter I with Evdokia Lopukhina. Little is known about the childhood of the young heir. The first years of his life he was mainly raised by his grandmother Natalya Kirillovna. At the age of eight, the prince lost his mother - Peter decided to send his unloved wife to a monastery. At the same time, the father began to initiate his son into government affairs, and after a couple of years - to take him on military campaigns. However, the heir made no progress in either field.

“When, at the height of the Northern War, King Charles XII of Sweden moved with troops to Moscow to capture it and dictate the terms of peace, Alexei, unlike Peter, who ordered to strengthen the Kremlin, asked one of his entourage to find a good place where he could hide. That is, Alexey was thinking not about Russia, but about himself. Peter I fought with his soldiers during the Battle of Poltava. But Tsarevich Alexei did not show any valor, he was completely unworthy of the title of a man,” said Pavel Krotov, Doctor of Historical Sciences, specialist in the history of Russia during the reign of Peter the Great, in a conversation with RT.

Alexey treated his father’s activities without any enthusiasm. Like his mother, the prince loved “old times” and hated any reformist changes.

- Portraits of Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich and Charlotte Christina of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

- Wikimedia Commons

In 1709, Peter sent his heir to study in Dresden. There, at the court of King Augustus, Alexei met his future wife, Princess Charlotte, who would later be called Natalya Petrovna in Russia. Two years later, by order of Peter I, their wedding took place.

By this time, Marta Skavronskaya, a former servant who was captured during the capture of the Swedish fortress and known as Catherine I, became the wife of Peter himself. The new empress gave birth to Peter two daughters, Anna and Elizabeth, and then another contender for the throne, Peter Petrovich.

After the birth of an heir from his second marriage, Alexei's position weakened. By this time, he had two children from the German princess: Natalya and Peter (the future Emperor Peter II, the last representative of the Romanovs in the direct male line).

“Liberal writers (for example, Daniil Granin) have their own version: he believes that Peter’s wife, Catherine, was intriguing against Alexei. If Alexei were on the throne, then all of her offspring would be under threat. Objectively, it was important for Catherine to eliminate Alexei,” noted Pavel Krotov.

Shortly after the birth of their son, Alexei’s wife died. After the funeral of Natalya Petrovna in October 1715, the prince received a letter from his father, irritated by the lack of will and inability of the heir to state affairs: “... I thought with sorrow and, seeing that I could not incline you to good, for the sake of goodness I invented this last testament to write to you and it’s not enough to wait, even if you turn unhypocritically. If not, then be aware that I will greatly deprive you of your inheritance, like a gangrenous oud, and do not imagine that I am only writing this for fear: truly I will fulfill it, for for my fatherland and people I have not and do not regret my life, then How can I feel sorry for you indecently? It’s better to be someone else’s good person than your own indecent one.”

In a response letter, Alexey renounced the inheritance and stated that he would never lay claim to the throne. But Peter was not satisfied with this answer. The emperor suggested that he either become less wayward and behave worthy of the future crown, or go to a monastery. Alexei decided to become a monk. But my father could not come to terms with such an answer. Then the prince went on the run.

In November 1716, under the fictitious name of a Polish nobleman, he arrived in Vienna, into the domain of Emperor Charles VI, who was Alexei's brother-in-law.

“Documentary evidence has been preserved that when Tsarevich Alexei fled to the West, to Austria, then to Italy, he entered into negotiations with the enemy of Russia, King Charles XII of Sweden, so that he would probably help him get the Russian crown. This is no longer worthy of the title of not only a ruler, but also a person,” emphasized Pavel Krotov.

The tragic end of the prodigal son

Having learned about his son’s escape, Peter I sent his associates, Peter Tolstoy and Alexander Rumyantsev, to search for him, giving them the following instructions: “They should go to Vienna and in a private audience announce to the Caesar that we have truly been informed through Captain Rumyantsev that our son Alexei has been accepted under the protection of the crown prince and was sent secretly to the Tyrolean castle of Ehrenberg, and was quickly sent from that castle, behind a strong guard, to the city of Naples, where he was kept on guard in the fortress, to which Captain Rumyantsev witnessed it.”

- Paul Delaroche, portrait of Peter I (1838)

Judging by this instruction, Peter called on the prodigal son to return to Russia, promising him all support and the absence of fatherly anger for disobedience. If the prince declared to Tolstoy and Rumyantsev that he did not intend to return to his homeland, then they were ordered to announce to Alexei the parental and church curse.

After much persuasion, the prince returned to Russia in the fall of 1717.

The emperor kept his promise and decided to pardon his son, but only under certain conditions. The prince had to refuse to inherit the crown and hand over the assistants who organized his escape. Alexei accepted all his father’s conditions and on February 3, 1718, renounced his rights to the throne.

At the same time, a series of investigations and interrogations of everyone close to the court began. Peter's associates demanded to know the details of the alleged conspiracy against the emperor.

In June 1718, the prince was put in the Peter and Paul Fortress and began to be tortured, demanding to confess to conspiring with foreign enemies. Under threats, Alexei admitted that he had negotiated with Charles VI and hoped that Austrian intervention would help him seize power in the country. And although Alexey wrote all his testimony in the subjunctive mood, without the slightest hint of the actual actions he took, it turned out to be enough for the trial. He was sentenced to death, which, however, was never carried out - Alexei suddenly died.

His death is still shrouded in mystery. According to the official version, Alexey took the news of the verdict very hard, which is why he fell into unconsciousness and died. Also, various sources indicate that the prince could have died from torture, was poisoned or strangled with a pillow. Historians are still arguing about what actually happened.

Alexei was buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral. Since the death of the prince coincided with the celebration of the anniversary of the victory in the Battle of Poltava, the emperor decided not to declare mourning.

- Still from the film “Tsarevich Alexei” (1996)

“Peter eliminated him as a person who would destroy all the achievements of state reform. Peter acted like the emperors of Ancient Rome, who executed their sons for state crimes. Peter acted not as a person, but as a statesman, for whom the main thing was not personal, but the interests of the country, which were threatened by an unworthy son, in fact a state criminal. In addition, Alexey was going to lead the measured life of an ordinary person, and at the head of Russia there was supposed to be a “locomotive” that would continue the work of Peter,” explained Pavel Krotov.

The fate of Alexei’s children also turned out to be tragic. Daughter Natalya died in 1728. Son Peter, having ascended the throne in 1727, after the death of Catherine I, died three years later.

Thus, in 1730, the male line of the Romanovs was interrupted in a straight line.

Tsarevich Alexei is a very unpopular personality not only among novelists, but also among professional historians. He is usually portrayed as a weak-willed, sickly, almost weak-minded young man who dreams of returning to the order of old Moscow Rus', avoids cooperation with his famous father in every possible way and is absolutely unfit to rule a huge empire. Peter I, who sentenced him to death, on the contrary, is portrayed in the works of Russian historians and novelists as a hero from ancient times, sacrificing his son to public interests and deeply suffering from his tragic decision.

Peter I interrogates Tsarevich Alexei in Peterhof. Artist N.N. Ge

“Peter, in his grief as a father and the tragedy of a statesman, arouses sympathy and understanding... In the entire unsurpassed gallery of Shakespearean images and situations, it is difficult to find anything similar in its tragedy,” writes, for example, N. Molchanov. And indeed, what else could the unfortunate emperor do if his son intended to return the capital of Russia to Moscow (by the way, where is it now?), “abandon the fleet” and remove his faithful comrades from governing the country? The fact that the “chicks of Petrov’s nest” managed well without Alexei and destroyed each other on their own (even the incredibly cautious Osterman had to go into exile after the accession of the beloved daughter of the prudent emperor) does not bother anyone. The Russian fleet, despite the death of Alexei, for some reason still fell into decay - there were a lot of admirals, and the ships existed mainly on paper. In 1765, Catherine II complained in a letter to Count Panin: “We have neither a fleet nor sailors.” But who cares? The main thing, as official historiographers of the Romanovs and Soviet historians who agree with them say, is that the death of Alexei allowed our country to avoid returning to the past.

And only a rare reader of near-historical novels will come up with a strange and seditious thought: what if it was precisely such a ruler, who did not inherit the temperament and warlike disposition of his father, that mortally tired and ruined Russia needed? So-called charismatic leaders are good in small doses; two great reformers in a row are too much: the country can break down. In Sweden, for example, after the death of Charles XII, there is a clear shortage of people who are ready to sacrifice the lives of several tens of thousands of their fellow citizens in the name of great goals and the public good. The Swedish Empire did not materialize, Finland, Norway and the Baltic states were lost, but no one in this country is lamenting about this.

Of course, comparing Russians and Swedes is not entirely correct, because... The Scandinavians got rid of excessive passionarity back in the Viking era. Having scared Europe to death with terrible berserker warriors (the last of whom can be considered Charles XII, who was lost in time) and, having provided the Icelandic skalds with the richest material for creating wonderful sagas, they could afford to take a place not on the stage, but in the stalls. The Russians, as representatives of a younger ethnic group, still had to splash out their energy and declare themselves as a great people. But for the successful continuation of the work begun by Peter, at a minimum it was necessary for a new generation of soldiers to grow up in a depopulated country, future poets, scientists, generals and diplomats to be born and educated. Until they come, nothing will change in Russia, but they will come, they will come very soon. V.K. Trediakovsky (1703), M.V. Lomonosov (1711) and A.P. Sumarokov (1717) were already born. In January 1725, two weeks before the death of Peter I, the future field marshal P.A. Rumyantsev was born, on February 8, 1728 - the founder of the Russian theater F.G. Volkov, on November 13, 1729 - A.V. Suvorov. Peter's successor must provide Russia with 10, or better yet, 20 years of peace. And Alexei’s plans are fully consistent with the historical situation: “I will keep the army only for defense, but I don’t want to have a war with anyone, I will be content with the old,” he tells his supporters in confidential conversations. Now think about it, is the unfortunate prince really so bad that even the reigns of the eternally drunk Catherine I, the creepy Anna Ioannovna and the cheerful Elizabeth should be considered a gift of fate? And is the dynastic crisis that shook the Russian empire in the first half of the 18th century and the subsequent era of palace coups that brought extremely dubious contenders to power, whose rule Germaine de Staël characterized as “autocracy limited by a stranglehold,” really such a good thing?

Before answering these questions, readers should be told that Peter I, who, according to V.O. Klyuchevsky, “ruined the country worse than any enemy,” was not at all popular among his subjects and was by no means perceived by them as a hero and savior of the fatherland. The era of Peter the Great for Russia became a time of bloody and not always successful wars, mass self-immolations of Old Believers and extreme impoverishment of all segments of the population of our country. Few people know that it was under Peter I that the classic “wild” version of Russian serfdom, known from many works of Russian literature, arose. And about the construction of St. Petersburg, V. Klyuchevsky said: “There is no battle that would claim so many lives.” It is not surprising that in the people's memory Peter I remained the oppressor tsar, and even more than that, the Antichrist, who appeared as punishment for the sins of the Russian people. The cult of Peter the Great began to be introduced into the national consciousness only during the reign of Elizabeth Petrovna. Elizabeth was the illegitimate daughter of Peter (she was born in 1710, the secret wedding of Peter I and Martha Skavronskaya took place in 1711, and their public wedding only in 1712) and therefore was never seriously considered by anyone as a contender for the throne . Having ascended to the Russian throne thanks to a palace coup carried out by a handful of soldiers of the Preobrazhensky Guards Regiment, Elizabeth spent her entire life fearing becoming a victim of a new conspiracy and, by glorifying the deeds of her father, sought to emphasize the legitimacy of her dynastic rights.

Subsequently, the cult of Peter I turned out to be extremely beneficial to another person with adventurous character traits - Catherine II, who, having overthrown the grandson of the first Russian emperor, declared herself the heir and continuer of the work of Peter the Great. To emphasize the innovative and progressive nature of the reign of Peter I, official historians of the Romanovs had to resort to forgery and attribute to him some innovations that became widespread under his father Alexei Mikhailovich and brother Fyodor Alekseevich. The Russian Empire in the second half of the 18th century was on the rise; great heroes and enlightened monarchs of the educated part of society were needed much more than tyrants and despots. Therefore, it is not surprising that by the beginning of the 19th century, admiration for the genius of Peter began to be considered good manners among the Russian nobility.

However, the attitude of the common people towards this emperor remained generally negative, and the genius of A.S. was required. Pushkin in order to radically change it. The great Russian poet was a good historian and intelligently understood the inconsistency of the activities of his beloved hero: “I have now sorted out a lot of materials about Peter and will never write his story, because there are many facts that I cannot agree with in any way with my personal respect for him,” - he wrote in 1836. However, you cannot command your heart, and the poet easily defeated the historian. It was with the light hand of Pushkin that Peter I became a true idol of the broad masses of Russia. With the strengthening of the authority of Peter I, the reputation of Tsarevich Alexei perished completely and irrevocably: if the great emperor, tirelessly concerned about the good of the state and his subjects, suddenly begins to personally torture, and then signs an order for the execution of his own son and heir, then there was a reason. The situation is like the German proverb: if a dog was killed, it means it had scabies. But what really happened in the imperial family?

In January 1689, 16-year-old Peter I, at the insistence of his mother, married Evdokia Fedorovna Lopukhina, who was three years older than him. Such a wife, who grew up in a closed mansion and was very far from the vital interests of young Peter, of course, did not suit the future emperor. Very soon, the unfortunate Evdokia became for him the personification of the hated order of old Moscow Rus', boyar laziness, arrogance and inertia. Despite the birth of children (Alexey was born on February 8, 1690, then Alexander and Pavel were born, who died in infancy), relations between the spouses were very strained. Peter's hatred and contempt for his wife could not but be reflected in his attitude towards his son. The denouement came on September 23, 1698: by order of Peter I, Queen Eudokia was taken to the Intercession Suzdal Nunnery, where she was forcibly tonsured a nun.

In the history of Russia, Evdokia became the only queen who, when imprisoned in a monastery, was not assigned any maintenance and was not assigned servants. In the same year, the Streltsy regiments were cashed out, a year before these events a decree on shaving beards was published, and the next year a new calendar was introduced and a decree on clothing was signed: the tsar changed everything - his wife, the army, the appearance of his subjects, and even time. And only the son, in the absence of another heir, remained the same for now. Alexei was 9 years old when Peter I’s sister Natalya snatched the boy from the hands of his mother, who was forcibly taken to the monastery. From then on, he began to live under the supervision of Natalya Alekseevna, who treated him with undisguised hatred. The prince saw his father rarely and, apparently, did not suffer much from separation from him, since he was far from delighted with Peter’s unceremonious favorites and the noisy feasts received in his circle. However, it has been proven that Alexey never showed open dissatisfaction with his father. He also did not shy away from studying: it is known that the prince had a good knowledge of history and sacred books, mastered the French and German languages perfectly, studied 4 operations of arithmetic, which was quite a lot for Russia at the beginning of the 18th century, and had the concept of fortification. Peter I himself, at the age of 16, could boast only of the ability to read, write and knowledge of two arithmetic operations. And Alexei’s older contemporary, the famous French king Louis XIV, may seem ignorant compared to our hero.

At the age of 11, Alexey traveled with Peter I to Arkhangelsk, and a year later, with the rank of a soldier in a bombardment company, he already participated in the capture of the Nyenschanz fortress (May 1, 1703). Please note: “meek” Alexei first takes part in the war at the age of 12, his warlike father only at the age of 23! In 1704, 14-year-old Alexey was constantly in the army during the siege of Narva. The first serious disagreement between the emperor and his son occurred in 1706. The reason for this was a secret meeting with his mother: Alexey was called to Zholkva (now Nesterov near Lvov), where he received a severe reprimand. However, later the relationship between Peter and Alexei normalized, and the emperor sent his son to Smolensk to stockpile provisions and collect recruits. Peter I was dissatisfied with the recruits that Alexei sent, which he announced in a letter to the prince. However, the point here, apparently, was not a lack of zeal, but a difficult demographic situation that developed in Russia not without the help of Peter himself: “At that time, I couldn’t find a better one soon, but you deigned to send it soon,” he justifies himself. Alexey, and his father is forced to admit that he is right. April 25, 1707 Peter I sends Alexei to supervise the repair and construction of new fortifications in Kitay-Gorod and the Kremlin. The comparison is again not in favor of the famous emperor: 17-year-old Peter amuses himself with building small boats on Lake Pleshcheyevo, and his son at the same age is preparing Moscow for a possible siege by the troops of Charles XII. In addition, Alexei is entrusted with leading the suppression of the Bulavinsky uprising. In 1711, Alexey was in Poland, where he managed the procurement of provisions for the Russian army stationed abroad. The country was devastated by the war and therefore the activities of the prince were not crowned with much success.

A number of very authoritative historians emphasize in their works that Alexei in many cases was a “figurehead.” Agreeing with this statement, it should be said that the majority of his illustrious peers were the same nominal commanders and rulers. We calmly read reports that the twelve-year-old son of the famous Prince Igor Vladimir in 1185 commanded the squad of the city of Putivl, and his peer from Norway (the future king Olav the Holy) in 1007 ravaged the coasts of Jutland, Frisia and England. But only in the case of Alexey we maliciously notice: but he could not seriously lead because of his youth and inexperience.

So, until 1711, the emperor was quite tolerant of his son, and then his attitude towards Alexei suddenly changed sharply for the worse. What happened in that ill-fated year? On March 6, Peter I secretly married Martha Skavronskaya, and on October 14, Alexei married Crown Princess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel Charlotte Christina-Sophia. At this time, Peter I thought for the first time: who should now be the heir to the throne? To the son from an unloved wife, Alexei, or to the children of a dearly beloved woman, “Katerinushka’s dear friend,” who would soon, on February 19, 1712, become the Russian Empress Ekaterina Alekseevna? The relationship between an unloved father and a son unloved by his heart could hardly be called cloudless before, but now they are completely deteriorating. Alexei, who was previously afraid of Peter, now experiences panic when communicating with him and, in order to avoid a humiliating exam when returning from abroad in 1712, even shoots him in the palm. This case is usually presented as an illustration of the thesis about the pathological laziness of the heir and his inability to learn. However, let's imagine the composition of the “examination committee”. Here, with a pipe in his mouth, lounging on a chair, sits the not entirely sober Emperor Pyotr Alekseevich. Standing next to him, grinning impudently, is an illiterate member of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Great Britain, Alexander Danilych Menshikov. Other “chicks of Petrov’s nest” crowd nearby, who carefully monitor any reaction of their master: if he smiles, they will rush to kiss him, if he frowns, they will trample on him without any pity. Would you like to be in Alexey's place?

As other evidence of the “unfitness” of the heir to the throne, the prince’s own letters to his father are often cited, in which he characterizes himself as a lazy, uneducated, physically and mentally weak person. Here it should be said that until the time of Catherine II, only one person had the right to be smart and strong in Russia - the ruling monarch. All the rest, in official documents addressed to the tsar or emperor, called themselves “poor in mind,” “poor,” “slow serfs,” “unworthy slaves,” and so on, so on, so on. Therefore, by humiliating himself, Alexei, firstly, follows the generally accepted rules of good manners, and secondly, demonstrates his loyalty to his father-emperor. And we won’t even talk about testimony obtained under torture in this article.

After 1711, Peter I began to suspect his son and daughter-in-law of treachery and in 1714 he sent Mrs. Bruce and Abbess Rzhevskaya to monitor how the birth of the Crown Princess would proceed: God forbid, they would replace a stillborn child and finally close the path to the top for Catherine’s children. A girl is born and the situation temporarily loses its urgency. But on October 12, 1715, a boy was born into Alexei’s family - the future Emperor Peter II, and on October 29 of the same year, the son of Empress Catherine Alekseevna, also named Peter, was born. Alexei’s wife dies after giving birth, and at her funeral the emperor hands his son a letter demanding that he “improperly correct himself.” Peter reproaches his 25-year-old son, who served not brilliantly, but served fairly well, for his dislike for military affairs and warns: “Don’t imagine that you are my only son.” Alexei understands everything correctly: on October 31, he renounces his claims to the throne and asks his father to let him go to the monastery. And Peter I was afraid: in the monastery, Alexei, having become inaccessible to secular authorities, would still be dangerous for Catherine’s long-awaited and previously beloved son. Peter knows perfectly well how his subjects treat him and understands that the pious son, who innocently suffered from the tyranny of his “Antichrist” father, will certainly be called to power after his death: the hood is not nailed to his head. At the same time, the emperor cannot clearly resist Alexei’s pious desire. Peter orders his son to “think” and takes a “time out” - he goes abroad. In Copenhagen, Peter I makes another move: he offers his son a choice: go to a monastery, or go (not alone, but with his beloved woman - Euphrosyne!) to join him abroad. This is very similar to a provocation: the prince, driven to despair, is given the opportunity to escape, so that he can later be executed for treason.

In the 30s of the twentieth century, Stalin tried to repeat this trick with Bukharin. In February 1936, in the hope that the “party favorite”, severely criticized in Pravda, would run away and ruin his good name forever, he sent him and his beloved wife to Paris. Bukharin, to the great disappointment of the leader of the peoples, returned.

And naive Alexey fell for the bait. Peter calculated correctly: Alexey was not going to betray his homeland and therefore did not ask for asylum in Sweden (“Hertz, this evil genius of Charles XII ... terribly regretted that he could not use Alexey’s betrayal against Russia,” writes N. Molchanov) or in Turkey. There was no doubt that from these countries Alexei, after the death of Peter I, would sooner or later return to Russia as emperor, but the prince preferred neutral Austria. The Austrian emperor had no need to quarrel with Russia, and therefore it was not difficult for Peter’s emissaries to return the fugitive to his homeland: “Sent to Austria by Peter to return Alexei, P.A. Tolstoy managed to complete his task with amazing ease... The Emperor hastened to get rid of his guest” (N. Molchanov).

In a letter dated November 17, 1717, Peter I solemnly promises his son forgiveness, and on January 31, 1718, the prince returns to Moscow. And already on February 3, arrests begin among the heir’s friends. They are tortured and forced to give the necessary testimony. On March 20, the notorious Secret Chancellery was created to investigate the prince’s case. June 19, 1718 was the day the torture of Alexei began. He died from these tortures on June 26 (according to other sources, he was strangled so as not to carry out the death sentence). And the very next day, June 27, Peter I threw a luxurious ball on the occasion of the anniversary of the Poltava victory.

So there was no trace of any internal struggle and no hesitation of the emperor. It all ended very sadly: on April 25, 1719, the son of Peter I and Ekaterina Alekseevna died. The autopsy showed that the boy was terminally ill from the moment of birth, and Peter I in vain killed his first son, clearing the path to the throne for the second.

ALEXEY PETROVICH

(18.II.1690 - 26.VI.1718) - Tsarevich, eldest son of Peter I from his first wife E. R. Lopukhina.

Until the age of 8, he was raised by his mother in an environment hostile to Peter I. He feared and hated his father and was reluctant to carry out his instructions, especially military ones. character. The lack of will and indecision of A.P. were used politically. enemies of Peter I. In 1705-06, the reactionary group grouped around the prince. the opposition of the clergy and boyars, opposing the reforms of Peter I. In Oct. 1711 A.P. married Princess Sophia Charlotte of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (d. 1715), with whom he had a son, Peter (later Peter II, 1715-30). Peter I, threatening disinheritance and imprisonment in a monastery, repeatedly demanded that A.P. change his behavior. In the end 1716, fearing punishment, A.P. fled to Vienna under the protection of the Austrians. imp. Charles VI. He hid in Ehrenberg Castle (Tirol), from May 1717 - in Naples. With threats and promises, Peter I achieved the return of his son (Jan. 1718) and forced him to renounce his rights to the throne and hand over his accomplices. On June 24, 1718, the supreme court of the generals, senators and Synod sentenced A.P. to death. According to the current version, he was strangled by the associates of Peter I in the Peter and Paul Fortress.

Soviet historical encyclopedia. - M.: Soviet Encyclopedia. Ed. E. M. Zhukova.

1973-1982.

Death of Peter I's son Alexei

How did Alexei really die? No one knew this then, and no one knows now. The death of the prince gave rise to rumors and disputes, first in St. Petersburg, then throughout Russia, and then in Europe.

Weber and de Lavie accepted the official explanation and reported to their capitals that the prince had died of apoplexy. But other foreigners doubted it, and various sensational versions were used. Player first reported that Alexei died of apoplexy, but three days later he informed his government that the prince was beheaded with a sword or an ax (many years later there was even a story about how Peter himself cut off his son’s head); According to rumors, some woman from Narva was brought to the fortress to have her head sewn back in place so that the prince’s body could be displayed for farewell. The Dutch resident de Bie reported that the prince was killed by draining all the blood from him, for which his veins were opened with a lancet. Later they also said that Alexei was strangled with pillows by four guards officers, and Rumyantsev was among them.

The truth is that to explain the death of Alexei, no additional reasons are needed, neither beheading, nor bloodletting, nor strangulation, nor even apoplexy.

Forty blows of the whip would have been enough to kill any big man, and Alexey was not strong, so mental shock and terrible wounds from forty blows on his skinny back could well have finished him off.

But be that as it may, Peter’s contemporaries believed that the death of the prince was the work of the king himself.

Many were shocked, but the general opinion was that Alexei's death solved all of Peter's problems.

Peter did not shy away from accusations. Although he said that it was the Lord who called Alexei to himself, he never denied that he himself brought Alexei to trial and sentenced him to death. The king did not have time to approve the verdict, but he completely agreed with the decision of the judges. He did not bother himself with hypocritical expressions of grief.

What can we say about this tragedy? Was it just a family drama, a clash of characters, in which a tyrannical father mercilessly torments and ultimately kills his pathetic, helpless son?

In Peter's relationship with his son, personal feelings were inseparably intertwined with political reality. Alexei’s character, of course, aggravated the confrontation between father and son, but at the heart of the conflict was the issue of supreme power. The two monarchs - one on the throne, the other awaiting the throne - had different ideas about the good of the state and set different goals for themselves.

But everyone faced bitter disappointment. While the reigning monarch sat on the throne, the son could only wait, but the monarch also knew that as soon as he was gone, his dreams would come to an end and everything would turn back.

Interrogations revealed that treacherous speeches were made and burning hopes for Peter's death were nurtured. Many were punished; So, was it possible to condemn these secondary culprits and leave the main one unharmed? This was precisely the choice that Peter faced, and it was the same one he proposed to the court. Peter himself, torn between his father's feelings and devotion to his life's work, chose the second.

Alexey was sentenced to death for reasons of state. As for Elizabeth I of England, this was a difficult decision of the monarch, who set the goal at all costs to “preserve” the state on which he had devoted his whole life to creating.

Biofile.ru›History›655.html

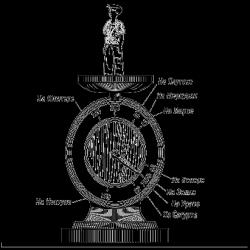

The purpose of this article is to find out the true cause of death of Tsarevich ALEXEY PETROVICH by his FULL NAME code.

Let's look at the FULL NAME code tables. \If there is a shift in numbers and letters on your screen, adjust the image scale\.

1 13 19 30 48 54 64 80 86 105 122 137 140 150 174 191 206 219 220 234 249 252

A L E K S E Y P E T R O V I C H R O M A N O V

252 251 239 233 222 204 198 188 172 166 147 130 115 112 102 78 61 46 33 32 18 3

17 32 45 46 60 75 78 79 91 97 108 126 132 142 158 164 183 200 215 218 228 252

R O M A N O V A L E K S E Y P E T R O V ICH

252 235 220 207 206 192 177 174 173 161 155 144 126 120 110 94 88 69 52 37 34 24

Knowing all the twists and turns in the final stage of the fate of ALEXEY PETROVICH, it is easy to succumb to temptation and decipher individual numbers as:

64 = EXECUTION. 80 = STRAIGHT.

But the numbers 122 = STROKE and 137 = APOPLEXY indicate the true cause of death.

And now we will make sure of this.

ROMANOV ALEXEY PETROVICH = 252 = 150-APOPPLEXIA OF THE M\brain\+ 102-...SIJA OF THE BRAIN.

252 = 179-BRAIN APOPLEXIA + 73-...SIYA M\brain\.

It should be noted that the word APOPLEXY is read openly: 1 = A...; 17 = AP...; 32 = APO...; 48 = APOP...; 60 = APOPL...; 105 = APOPLEXI...; 137 = APOPLEXIA.

174 = APOPPLEXIA OF THE MR\ha\

_____________________________

102 = ...BRAIN BRAIN

It seems that the most accurate decoding would be with the word STROKE. Let's check this with two tables: STROKE DEATH and DEATH BY STROKE.

10 24* 42 62 74 103 122*137*150* 168 181 187 204*223 252

I N S U L T O M DEATH

252 242 228*210 190 178 149 130*115* 102* 84 71 65 48* 29

We see the coincidence of the central column 137\\130 (the eighth - from left to right) with the column in the top table.

18* 31 37* 54* 73 102* 112*126*144*164*176 205 224 239*252

DEATH INSUL T O M

252 234*221 215*198*179 150*140*126*108* 88* 76 47 28 13*

We see the coincidence of two columns 112\\150 and 126\\144, and in our table column 112\\150 is seventh from the left, and column 126\\144 is seventh from the right.

262 = APOPLEXIA OF THE BRAIN\.

Code for the number of full YEARS OF LIFE: 86-TWENTY + 84-EIGHT = 170 = 101-DEAD + 69-END.

Let's look at the column in the top table:

122 = TWENTY SUN\ is \ = STROKE

________________________________________

147 = 101-DECEASED + 46-KONE\ts\

147 - 122 = 25 = UGA\s\.

170 = 86-\ 43-IMPACT + 43-EXHAUS\ + 84-BRAIN.

170 = 127-BRAIN BLOW + 43-EXHAUSTION.

We will find the number 127 = BRAIN Stroke if we add up the letter codes that are included in the FULL NAME code only once:

L=12 + K=11 + S=18 + P=16 + T=19 + H=24 + M=13 + H=14 = 127.