Nicholas II: the tsar who was out of place. Ascended Lord Nicholas Nicholas II entered

Professor Sergei Mironenko about the personality and fatal mistakes of the last Russian emperor

In the year of the 100th anniversary of the revolution, conversations about Nicholas II and his role in the tragedy of 1917 do not stop: truth and myths are often mixed in these conversations. Scientific director of the State Archive of the Russian Federation Sergei Mironenko- about Nicholas II as a man, ruler, family man, passion-bearer.

“Nicky, you’re just some kind of Muslim!”

Sergei Vladimirovich, in one of your interviews you called Nicholas II “frozen.” What did you mean? What was the emperor like as a person, as a person?

Nicholas II loved the theater, opera and ballet, and loved physical exercise. He had unpretentious tastes. He liked to drink a glass or two of vodka. Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich recalled that when they were young, he and Niki once sat on the sofa and kicked with their feet, who would knock whom off the sofa. Or another example - a diary entry during a visit to relatives in Greece about how wonderfully he and his cousin Georgie were left with oranges. He was already quite a grown-up young man, but something childish remained in him: throwing oranges, kicking. Absolutely alive person! But still, it seems to me, he was some kind of... not a daredevil, not “eh!” You know, sometimes meat is fresh, and sometimes it’s first frozen and then defrosted, do you understand? In this sense - “frostbitten”.

Sergey Mironenko

Photo: DP28

Restrained? Many noted that he very dryly described terrible events in his diary: the shooting of a demonstration and the lunch menu were nearby. Or that the emperor remained absolutely calm when receiving difficult news from the front of the Japanese War. What does this indicate?

In the imperial family, keeping a diary was one of the elements of education. A person was taught to write down at the end of the day what happened to him, and thus give himself an account of how you lived that day. If the diaries of Nicholas II were used for the history of weather, then this would be a wonderful source. “Morning, so many degrees of frost, got up at such and such time.” Always! Plus or minus: “sunny, windy” - he always wrote it down.

His grandfather Emperor Alexander II kept similar diaries. The War Ministry published small memorial books: each sheet was divided into three days, and Alexander II managed to write down his entire day on such a small sheet of paper all day, from the moment he got up until he went to bed. Of course, this was a recording of only the formal side of life. Basically, Alexander II wrote down who he received, with whom he had lunch, with whom he had dinner, where he was, at a review or somewhere else, etc. Rarely, rarely does something emotional break through. In 1855, when his father, Emperor Nicholas I, was dying, he wrote down: “It’s such and such an hour. The last terrible torment." This is a different type of diary! And Nikolai’s emotional assessments are extremely rare. In general, he apparently was an introvert by nature.

- Today you can often see in the press a certain average image of Tsar Nicholas II: a man of noble aspirations, an exemplary family man, but a weak politician. How true is this image?

As for the fact that one image has become established, this is wrong. There are diametrically opposed points of view. For example, academician Yuri Sergeevich Pivovarov claims that Nicholas II was a major, successful statesman. Well, you yourself know that there are many monarchists who bow to Nicholas II.

I think that this is just the right image: he really was a very good person, a wonderful family man and, of course, a deeply religious man. But as a politician, I was absolutely out of place, I would say so.

Coronation of Nicholas II

When Nicholas II ascended the throne, he was 26 years old. Why, despite his brilliant education, was he not ready to be a king? And there is evidence that he did not want to ascend the throne and was burdened by it?

Behind me are the diaries of Nicholas II, which we published: if you read them, everything becomes clear. He was actually a very responsible person, he understood the whole burden of responsibility that fell on his shoulders. But, of course, he did not think that his father, Emperor Alexander III, would die at 49, he thought that he still had some time left. Nicholas was burdened by the ministers' reports. Although one can have different attitudes towards Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, I believe he was absolutely right when he wrote about the traits characteristic of Nicholas II. For example, he said that with Nikolai, the one who came to him last is right. Various issues are being discussed, and Nikolai takes the point of view of the one who came into his office last. Maybe this was not always the case, but this is a certain vector that Alexander Mikhailovich is talking about.

Another of his features is fatalism. Nikolai believed that since he was born on May 6, the day of Job the Long-Suffering, he was destined to suffer. Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich told him: “Niki (that was Nikolai’s name in the family), you're just some kind of Muslim! We have the Orthodox faith, it gives free will, and your life depends on you, there is no such fatalistic destiny in our faith.” But Nikolai was sure that he was destined to suffer.

In one of your lectures you said that he really suffered a lot. Do you think that this was somehow connected with his mentality and attitude?

You see, every person makes his own destiny. If you think from the very beginning that you are made to suffer, in the end you will in life!

The most important misfortune, of course, is that they had a terminally ill child. This cannot be discounted. And it turned out literally immediately after birth: the Tsarevich’s umbilical cord was bleeding... This, of course, frightened the family; they hid for a very long time that their child had hemophilia. For example, the sister of Nicholas II, Grand Duchess Ksenia, found out about this almost 8 years after the heir was born!

Then, difficult situations in politics - Nicholas was not ready to rule the vast Russian Empire in such a difficult period of time.

About the birth of Tsarevich Alexei

The summer of 1904 was marked by a joyful event, the birth of the unfortunate Tsarevich. Russia had been waiting for an heir for so long, and how many times had this hope turned into disappointment that his birth was greeted with enthusiasm, but the joy did not last long. Even in our house there was despondency. The uncle and aunt undoubtedly knew that the child was born with hemophilia, a disease characterized by bleeding due to the inability of the blood to clot quickly. Of course, the parents quickly learned about the nature of their son’s illness. One can imagine what a terrible blow this was for them; from that moment on, the empress’s character began to change, and her health, both physical and mental, began to deteriorate from painful experiences and constant anxiety.

- But he was prepared for this from childhood, like any heir!

You see, whether you cook or not, you can’t discount a person’s personal qualities. If you read his correspondence with his bride, who later became Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, you will see that he writes to her about how he rode twenty miles and feels good, and she writes to him about how she was in church, how she prayed. Their correspondence shows everything, from the very beginning! Do you know what he called her? He called her “owl”, and she called him “calf”. Even this one detail gives a clear picture of their relationship.

Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna

Initially, the family was against his marriage to the Princess of Hesse. Can we say that Nicholas II showed character here, some strong-willed qualities, insisting on his own?

They weren't entirely against it. They wanted to marry him to a French princess - because of the turn in the foreign policy of the Russian Empire from an alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary to an alliance with France that emerged in the early 90s of the 19th century. Alexander III wanted to strengthen family ties with the French, but Nicholas categorically refused. A little-known fact - Alexander III and his wife Maria Feodorovna, when Alexander was still just the heir to the throne, became the successors of Alice of Hesse - the future Empress Alexandra Feodorovna: they were the young godmother and father! So, there were still connections. And Nikolai wanted to get married at all costs.

- But he was still a follower?

Of course there was. You see, we must distinguish between stubbornness and will. Very often weak-willed people are stubborn. I think that in a certain sense Nikolai was like that. There are wonderful moments in their correspondence with Alexandra Fedorovna. Especially during the war, when she writes to him: “Be Peter the Great, be Ivan the Terrible!” and then adds: “I see how you smile.” She writes to him “be,” but she herself understands perfectly well that he cannot be, by character, the same as his father was.

For Nikolai, his father was always an example. He wanted, of course, to be like him, but he couldn’t.

Dependence on Rasputin led Russia to destruction

- How strong was Alexandra Feodorovna’s influence on the emperor?

Alexandra Fedorovna had a huge influence on him. And through Alexandra Feodorovna - Rasputin. And, by the way, relations with Rasputin became one of the rather strong catalysts for the revolutionary movement and general dissatisfaction with Nicholas. It was not so much the figure of Rasputin himself that caused discontent, but the image created by the press of a dissolute old man who influences political decision-making. Add to this the suspicion that Rasputin is a German agent, which was fueled by the fact that he was against the war with Germany. Rumors spread that Alexandra Fedorovna was a German spy. In general, everything rolled along a well-known road, which ultimately led to renunciation...

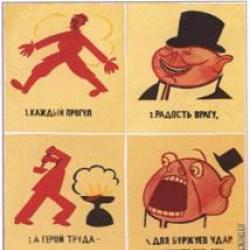

Caricature of Rasputin

Peter Stolypin

- What other political mistakes became fatal?

There were many of them. One of them is distrust of outstanding statesmen. Nikolai could not save them, he could not! The example of Stolypin is very indicative in this sense. Stolypin is truly an outstanding person. Outstanding not only and not so much because he uttered in the Duma those words that are now being repeated by everyone: “You need great upheavals, but we need a great Russia.”

That's not why! But because he understood: the main obstacle in a peasant country is the community. And he firmly pursued the policy of destroying the community, and this was contrary to the interests of a fairly wide range of people. After all, when Stolypin arrived in Kyiv as prime minister in 1911, he was already a “lame duck.” The issue of his resignation was resolved. He was killed, but the end of his political career came earlier.

In history, as you know, there is no subjunctive mood. But I really want to dream up. What if Stolypin had been at the head of the government longer, if he had not been killed, if the situation had turned out differently, what would have happened? If Russia had so recklessly entered into a war with Germany, would the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand be worth getting involved in this world war?..

1908 Tsarskoye Selo. Rasputin with the Empress, five children and governess

However, I really want to use the subjunctive mood. The events taking place in Russia at the beginning of the twentieth century seem so spontaneous, irreversible - the absolute monarchy has outlived its usefulness, and sooner or later what happened would have happened; the personality of the tsar did not play a decisive role. This is wrong?

You know, this question, from my point of view, is useless, because the task of history is not to guess what would have happened if, but to explain why it happened this way and not otherwise. This has already happened. But why did it happen? After all, history has many paths, but for some reason it chooses one out of many, why?

Why did it happen that the previously very friendly, close-knit Romanov family (the ruling house of the Romanovs) turned out to be completely split by 1916? Nikolai and his wife were alone, but the whole family - I emphasize, the whole family - was against it! Yes, Rasputin played his role - the family split largely because of him. Grand Duchess Elizaveta Feodorovna, sister of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, tried to talk to her about Rasputin, to dissuade her - it was useless! Nicholas's mother, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, tried to speak - it was useless.

In the end, it came to a grand-ducal conspiracy. Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich, the beloved cousin of Nicholas II, took part in the murder of Rasputin. Grand Duke Nikolai Mikhailovich wrote to Maria Feodorovna: “The hypnotist has been killed, now it’s the hypnotized woman’s turn, she must disappear.”

They all saw that this indecisive policy, this dependence on Rasputin was leading Russia to destruction, but they could not do anything! They thought that they would kill Rasputin and things would somehow get better, but they didn’t get better - everything had gone too far. Nikolai believed that relations with Rasputin were a private matter of his family, in which no one had the right to interfere. He did not understand that the emperor could not have a private relationship with Rasputin, that the matter had taken a political turn. And he cruelly miscalculated, although as a person one can understand him. So personality definitely matters a lot!

About Rasputin and his murder

From the memoirs of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna

Everything that happened to Russia thanks to the direct or indirect influence of Rasputin can, in my opinion, be considered as a vengeful expression of the dark, terrible, all-consuming hatred that for centuries burned in the soul of the Russian peasant in relation to the upper classes, who did not try to understand him or attract him to your side. Rasputin loved both the empress and the emperor in his own way. He felt sorry for them, as one feels sorry for children who have made a mistake due to the fault of adults. They both liked his apparent sincerity and kindness. His speeches - they had never heard anything like it before - attracted them with its simple logic and novelty. The emperor himself sought closeness with his people. But Rasputin, who had no education and was not accustomed to such an environment, was spoiled by the boundless trust that his high patrons showed him.

Emperor Nicholas II and Supreme Commander-in-Chief led. Prince Nikolai Nikolaevich during the inspection of the fortifications of the Przemysl fortress

Is there evidence that Empress Alexandra Feodorovna directly influenced her husband’s specific political decisions?

Certainly! At one time there was a book by Kasvinov, “23 Steps Down,” about the murder of the royal family. So, one of the most serious political mistakes of Nicholas II was the decision to become the supreme commander in chief in 1915. This was, if you like, the first step to renunciation!

- And only Alexandra Fedorovna supported this decision?

She convinced him! Alexandra Feodorovna was a very strong-willed, very smart and very cunning woman. What was she fighting for? For the future of their son. She was afraid that Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich (Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army in 1914-1915 - ed.), who was very popular in the army, will deprive Niki of the throne and become emperor himself. Let's leave aside the question of whether this really happened.

But, believing in Nikolai Nikolaevich’s desire to take the Russian throne, the empress began to engage in intrigue. “In this difficult time of testing, only you can lead the army, you must do it, this is your duty,” she persuaded her husband. And Nikolai succumbed to her persuasion, sent his uncle to command the Caucasian Front and took command of the Russian army. He did not listen to his mother, who begged him not to take a disastrous step - she just perfectly understood that if he became commander-in-chief, all failures at the front would be associated with his name; nor the eight ministers who wrote him a petition; nor the Chairman of the State Duma Rodzianko.

The emperor left the capital, lived for months at headquarters, and as a result was unable to return to the capital, where a revolution took place in his absence.

Emperor Nicholas II and front commanders at a meeting of Headquarters

Nicholas II at the front

Nicholas II with generals Alekseev and Pustovoitenko at Headquarters

What kind of person was the empress? You said - strong-willed, smart. But at the same time, she gives the impression of a sad, melancholy, cold, closed person...

I wouldn't say she was cold. Read their letters - after all, in letters a person opens up. She is a passionate, loving woman. A powerful woman who fights for what she considers necessary, fighting for the throne to be passed on to her son, despite his terminal illness. You can understand her, but, in my opinion, she lacked breadth of vision.

We will not talk about why Rasputin acquired such influence over her. I am deeply convinced that the matter is not only about the sick Tsarevich Alexei, whom he helped. The fact is, the empress herself needed a person who would support her in this hostile world. She arrived, shy, embarrassed, and in front of her was the rather strong Empress Maria Feodorovna, whom the court loved. Maria Feodorovna loves balls, but Alix doesn’t like balls. St. Petersburg society is accustomed to dancing, accustomed, accustomed to having fun, but the new empress is a completely different person.

Nicholas II with his mother Maria Fedorovna

Nicholas II with his wife

Nicholas II with Alexandra Feodorovna

Gradually, the relationship between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law gets worse and worse. And in the end it comes to a complete break. Maria Fedorovna, in her last diary before the revolution, in 1916, calls Alexandra Fedorovna only “fury.” “This fury” - she can’t even write her name...

Elements of the great crisis that led to abdication

- However, Nikolai and Alexandra were a wonderful family, right?

Of course, a wonderful family! They sit, read books to each other, their correspondence is wonderful and tender. They love each other, they are spiritually close, physically close, they have wonderful children. Children are different, some of them are more serious, some, like Anastasia, are more mischievous, some smoke secretly.

About the atmosphere in Nikolai’s family II and Alexandra Feodorovna

From the memoirs of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna

The Emperor and his wife were always affectionate in their relationships with each other and their children, and it was so pleasant to be in an atmosphere of love and family happiness.

At a costume ball. 1903

But after the murder of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich (Governor General of Moscow, uncle of Nicholas II, husband of Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna - ed.) in 1905, the family locked themselves in Tsarskoye Selo, not a single big ball again, the last big ball took place in 1903, a costume ball, where Nikolai dressed as Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, Alexandra dressed as the queen. And then they become more and more isolated.

Alexandra Fedorovna did not understand a lot of things, did not understand the situation in the country. For example, failures in the war... When they tell you that Russia almost won the First World War, do not believe it. A serious socio-economic crisis was growing in Russia. First of all, it manifested itself in the inability of the railways to cope with freight flows. It was impossible to simultaneously transport food to large cities and transport military supplies to the front. Despite the railway boom that began under Witte in the 1880s, Russia, compared to European countries, had a poorly developed railway network.

Groundbreaking ceremony for the Trans-Siberian Railway

- Despite the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway, was this not enough for such a large country?

Absolutely! This was not enough; the railways could not cope. Why am I talking about this? When food shortages began in Petrograd and Moscow, what does Alexandra Fedorovna write to her husband? "Our Friend advises (Friend – that’s what Alexandra Fedorovna called Rasputin in her correspondence. – ed.): order one or two wagons with food to be attached to each train that is sent to the front.” To write something like this means that you are completely unaware of what is happening. This is a search for simple solutions, solutions to a problem whose roots do not lie in this at all! What is one or two carriages for the multimillion-dollar Petrograd and Moscow?..

Yet it grew!

Prince Felix Yusupov, participant in the conspiracy against Rasputin

Two or three years ago we received the Yusupov archive - Viktor Fedorovich Vekselberg bought it and donated it to the State Archive. This archive contains letters from teacher Felix Yusupov in the Corps of Pages, who went with Yusupov to Rakitnoye, where he was exiled after participating in the murder of Rasputin. Two weeks before the revolution he returned to Petrograd. And he writes to Felix, who is still in Rakitnoye: “Can you imagine that in two weeks I have not seen or eaten a single piece of meat?” No meat! Bakeries are closed because there is no flour. And this is not the result of some malicious conspiracy, as is sometimes written about, which is complete nonsense and nonsense. And evidence of the crisis that has gripped the country.

The leader of the Kadet Party, Miliukov, speaks in the State Duma - he seems to be a wonderful historian, a wonderful person, but what does he say from the Duma rostrum? He throws accusation after accusation at the government, of course, addressing them to Nicholas II, and ends each passage with the words: “What is this? Stupidity or treason? The word “treason” has already been thrown around.

It's always easy to blame your failures on someone else. It’s not us who fight badly, it’s treason! Rumors begin to circulate that the Empress has a direct golden cable laid from Tsarskoe Selo to Wilhelm’s headquarters, that she is selling state secrets. When she arrives at headquarters, the officers are defiantly silent in her presence. It's like a snowball growing! The economy, the railway crisis, failures at the front, the political crisis, Rasputin, the family split - all these are elements of a great crisis, which ultimately led to the abdication of the emperor and the collapse of the monarchy.

By the way, I am sure that those people who thought about the abdication of Nicholas II, and he himself, did not at all imagine that this was the end of the monarchy. Why? Because they had no experience of political struggle, they did not understand that horses cannot be changed in midstream! Therefore, the commanders of the fronts, one and all, wrote to Nicholas that in order to save the Motherland and continue the war, he must abdicate the throne.

About the situation at the beginning of the war

From the memoirs of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna

At the beginning the war was successful. Every day a crowd of Muscovites staged patriotic demonstrations in the park opposite our house. People in the front rows held flags and portraits of the Emperor and Empress. With their heads uncovered, they sang the national anthem, shouted words of approval and greeting, and calmly dispersed. People perceived it as entertainment. Enthusiasm took on more and more violent forms, but the authorities did not want to interfere with this expression of loyal feelings, people refused to leave the square and disperse. The last gathering turned into rampant drinking and ended with bottles and rocks being thrown at our windows. The police were called and lined up along the sidewalk to block access to our house. Excited shouts and dull murmurs from the crowd could be heard from the street all night.

About the bomb in the temple and changing moods

From the memoirs of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna

On the eve of Easter, when we were in Tsarskoe Selo, a conspiracy was discovered. Two members of a terrorist organization, disguised as singers, tried to sneak into the choir, which sang at services in the palace church. Apparently, they planned to carry bombs under their clothes and detonate them in the church during the Easter service. The emperor, although he knew about the conspiracy, went with his family to church as usual. Many people were arrested that day. Nothing happened, but it was the saddest service I have ever attended.

Abdication of the throne by Emperor Nicholas II.

There are still myths about the abdication - that it had no legal force, or that the emperor was forced to abdicate...

This just surprises me! How can you say such nonsense? You see, the renunciation manifesto was published in all newspapers, in all of them! And in the year and a half that Nikolai lived after this, he never once said: “No, they forced me to do this, this is not my real renunciation!”

The attitude towards the emperor and empress in society is also “steps down”: from admiration and devotion to ridicule and aggression?

When Rasputin was killed, Nicholas II was at headquarters in Mogilev, and the Empress was in the capital. What is she doing? Alexandra Fedorovna calls the Petrograd Chief of Police and gives orders to arrest Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich and Yusupov, participants in the murder of Rasputin. This caused an explosion of indignation in the family. Who is she?! What right does she have to give orders to arrest someone? This proves 100% who rules us - not Nikolai, but Alexandra!

Then the family (mother, grand dukes and grand duchesses) turned to Nikolai with a request not to punish Dmitry Pavlovich. Nikolai put a resolution on the document: “I am surprised by your appeal to me. No one is allowed to kill! A decent answer? Of course yes! No one dictated this to him, he himself wrote it from the depths of his soul.

In general, Nicholas II as a person can be respected - he was an honest, decent person. But not too smart and without a strong will.

“I don’t feel sorry for myself, but I feel sorry for the people”

Alexander III and Maria Feodorovna

The famous phrase of Nicholas II after his abdication: “I don’t feel sorry for myself, but feel sorry for the people.” He really rooted for the people, for the country. How much did he know his people?

Let me give you an example from another area. When Maria Feodorovna married Alexander Alexandrovich and when they - then the Tsarevich and the Tsarevna - were traveling around Russia, she described such a situation in her diary. She, who grew up in a rather poor but democratic Danish royal court, could not understand why her beloved Sasha did not want to communicate with the people. He doesn’t want to leave the ship on which they were traveling to see the people, he doesn’t want to accept bread and salt, he’s absolutely not interested in all this.

But she arranged it so that he had to get off at one of the points on their route where they landed. He did everything flawlessly: he received the elders, bread and salt, and charmed everyone. He came back and... gave her a wild scandal: he stomped his feet and broke a lamp. She was terrified! Her sweet and beloved Sasha, who throws a kerosene lamp on the wooden floor, is about to set everything on fire! She couldn't understand why? Because the unity of the king and the people was like a theater where everyone played their roles.

Even chronicle footage of Nicholas II sailing away from Kostroma in 1913 has been preserved. People go chest-deep into the water, stretch out their hands to him, this is the Tsar-Father... and after 4 years these same people sing shameful ditties about both the Tsar and the Tsarina!

- The fact that, for example, his daughters were sisters of mercy, was that also theater?

No, I think it was sincere. They were, after all, deeply religious people, and, of course, Christianity and charity are practically synonymous. The girls really were sisters of mercy, Alexandra Fedorovna really assisted during operations. Some of the daughters liked it, some not so much, but they were no exception among the imperial family, among the House of Romanov. They gave up their palaces for hospitals - there was a hospital in the Winter Palace, and not only the emperor’s family, but also other grand duchesses. Men fought, and women did mercy. So mercy is not just ostentatious.

Princess Tatiana in the hospital

Alexandra Fedorovna - sister of mercy

Princesses with the wounded in the infirmary of Tsarskoe Selo, winter 1915-16

But in a sense, any court action, any court ceremony is a theater, with its own script, with its own characters, and so on.

Nikolay II and Alexandra Fedorovna in the hospital for the wounded

From the memoirs of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna

The Empress, who spoke Russian very well, walked around the wards and talked for a long time with each patient. I walked behind and not so much listened to the words - she told everyone the same thing - but watched the expressions on their faces. Despite the empress's sincere sympathy for the suffering of the wounded, something prevented her from expressing her true feelings and comforting those to whom she addressed. Although she spoke Russian correctly and almost without an accent, people did not understand her: her words did not find a response in their souls. They looked at her in fear when she approached and started a conversation. I visited hospitals with the emperor more than once. His visits looked different. The Emperor behaved simply and charmingly. With his appearance, a special atmosphere of joy arose. Despite his small stature, he always seemed taller than everyone present and moved from bed to bed with extraordinary dignity. After a short conversation with him, the expression of anxious expectation in the eyes of the patients was replaced by joyful animation.

1917 - This year marks the 100th anniversary of the revolution. How, in your opinion, should we talk about it, how should we approach discussing this topic? Ipatiev House

How was the decision made about their canonization? “Digged”, as you say, weighed. After all, the commission did not immediately declare him a martyr; there were quite big disputes on this matter. It was not for nothing that he was canonized as a passion-bearer, as one who gave his life for the Orthodox faith. Not because he was an emperor, not because he was an outstanding statesman, but because he did not abandon Orthodoxy. Until the very end of their martyrdom, the royal family constantly invited priests to serve mass, even in the Ipatiev House, not to mention Tobolsk. The family of Nicholas II was a deeply religious family.

- But even about canonization there are different opinions.

They were canonized as passion-bearers - what different opinions could there be?

Some insist that the canonization was hasty and politically motivated. What can I say to this?

From the report of Metropolitan Juvenaly of Krutitsky and Kolomna, pChairman of the Synodal Commission for the Canonization of Saints at the Bishops' Jubilee Council

... Behind the many sufferings endured by the Royal Family over the last 17 months of their lives, which ended with execution in the basement of the Ekaterinburg Ipatiev House on the night of July 17, 1918, we see people who sincerely sought to embody the commandments of the Gospel in their lives. In the suffering endured by the Royal Family in captivity with meekness, patience and humility, in their martyrdom, the evil-conquering light of Christ's faith was revealed, just as it shone in the life and death of millions of Orthodox Christians who suffered persecution for Christ in the twentieth century. It is in understanding this feat of the Royal Family that the Commission, in complete unanimity and with the approval of the Holy Synod, finds it possible to glorify in the Council the new martyrs and confessors of Russia in the guise of the passion-bearers Emperor Nicholas II, Empress Alexandra, Tsarevich Alexy, Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia.

- How do you generally assess the level of discussions about Nicholas II, about the imperial family, about 1917 today?

What is a discussion? How can you debate with the ignorant? In order to say something, a person must know at least something; if he does not know anything, it is useless to discuss with him. So much garbage has appeared about the royal family and the situation in Russia at the beginning of the twentieth century in recent years. But what is encouraging is that there are also very serious works, for example, studies by Boris Nikolaevich Mironov, Mikhail Abramovich Davydov, who are engaged in economic history. So Boris Nikolaevich Mironov has a wonderful work, where he analyzed the metric data of people who were called up for military service. When a person was called up for service, his height, weight, and so on were measured. Mironov was able to establish that in the fifty years that passed after the liberation of the serfs, the height of conscripts increased by 6-7 centimeters!

- So you started eating better?

Certainly! Life has become better! But what did Soviet historiography talk about? “Aggravation, higher than usual, of the needs and misfortunes of the oppressed classes,” “relative impoverishment,” “absolute impoverishment,” and so on. In fact, as I understand it, if you believe the works I named - and I have no reason not to believe them - the revolution occurred not because people began to live worse, but because, paradoxical as it may sound, it was better began to live! But everyone wanted to live even better. The situation of the people even after the reform was extremely difficult, the situation was terrible: the working day was 11 hours, terrible working conditions, but in the village they began to eat better and dress better. There was a protest against the slow movement forward; I wanted to go faster.

Sergey Mironenko.

Photo: Alexander Bury / russkiymir.ru

They don’t seek good from good, in other words? Sounds threatening...

Why?

Because I can’t help but want to draw an analogy with our days: over the past 25 years, people have learned that they can live better...

They don’t seek good from goodness, yes. For example, the Narodnaya Volya revolutionaries who killed Alexander II, the Tsar-Liberator, were also unhappy. Although he is a king-liberator, he is indecisive! If he doesn’t want to go further with reforms, he needs to be pushed. If he doesn’t go, we need to kill him, we need to kill those who oppress the people... You can’t isolate yourself from this. We need to understand why this all happened. I don’t advise you to draw analogies with today, because analogies are usually wrong.

Usually today they repeat something else: the words of Klyuchevsky that history is an overseer who punishes for ignorance of its lessons; that those who do not know their history are doomed to repeat its mistakes...

Of course, you need to know history not only in order to avoid making previous mistakes. I think the main thing for which you need to know your history is in order to feel like a citizen of your country. Without knowing your own history, you cannot be a citizen, in the truest sense of the word.

Nikolai was born in 1868 and was educated at home. The course at the General Staff Academy was taught to him by the future Minister of War A.F. Roediger, history - the famous V. O. Klyuchevsky, but the most significant influence on the heir’s worldview was exerted by his teacher K. P. Pobedonostsev, a former professor at Moscow University, chief prosecutor of the Synod. He convinced Nicholas is that an unlimited monarchy is the only possible type of political system Russia.

According to contemporaries, Nikolai did not have bright natural talents, he was not stupid, but shallow, and was distinguished by lack of will, secrecy and stubbornness. Despite the fact that dealing with government affairs has always been a burden Nicholas II, he did not allow the thought of giving up unlimited power.

The only sincere affection last Russian the emperor was his family. In 1894, Nikolai married Alexandra Feodorovna (Alice - Princess of Hesse and the Rhine). An excellent family man, Nicholas II devoted a lot of time and attention to children - after four daughters, his long-awaited heir was born in 1904.

Nicholas II considered autocratic power to be a purely family matter and was sincerely convinced that he must transfer it to his son in its entirety.

Already in January 1895, speaking to deputies from the nobility, zemstvos and cities, the young emperor, making a reservation, called the hopes that had spread in society for liberalization of the regime “meaningless dreams.”

Complete indifference Nicholas II to everything that went beyond the scope of court life and family relationships, clearly manifested itself in connection with the Khodynka tragedy. On the day of the emperor’s coronation in Moscow, May 18, 1896, about one and a half thousand people died in a stampede on Khodynskoye Field. Nicholas II not only did not cancel the festivities and did not declare mourning, but even took part in court entertainment events that same evening, and at the end of the celebrations he expressed gratitude for their “exemplary preparation and conduct” to the Governor General of Moscow - his uncle, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich .

It should be noted here that for Nicholas II it was very typical to appoint his relatives - the Grand Dukes of the Romanovs - to responsible positions, regardless of their personal qualities and abilities. As a result, during the most difficult time for the country - the years of crisis and war - people who were not only mediocre, but also uncontrollable, found themselves in key positions. Thus, the Tsar’s uncle Alexei Alexandrovich, who “sank” the Russian fleet during the war with Japan, ended up in the highest naval post; the position of inspector general of artillery was held by Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich; The main head of military educational institutions was Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, and the inspector general of the engineering unit was Grand Duke Pyotr Nikolaevich.

These appointments seemed to continue the traditions of Alexander III’s “personnel policy”: for example, from 1881 to 1905, the Chairman of the State Council was Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich, an extremely limited man. Of course, among the tsar’s relatives there were also capable and intelligent people, but Nicholas II did not listen to their opinion. The example of Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich is typical in this regard. Already in 1895, he presented a note to Nicholas II, where he named Japan as the most likely enemy Russia on sea and determined the time of the start of hostilities - 1903-1904, and during the war he categorically objected to sending the 1st and 2nd Pacific squadrons to the Far East; Alexander Mikhailovich developed a plan for the construction of new ships and reconstruction of ports, and published a number of reference books on the navy. However, when making decisions, Nicholas II valued the advice of older relatives more, giving preference to age rather than ability.

The “activities” of numerous holy fools, seers and blessed ones at the royal court caused enormous damage to the authority of the monarchy. But the most destructive was the influence of the “holy elder” Grigory Rasputin (G.E. Novykh), who became a symbol of decay Russian autocracy in the last years of the reign Nicholas II. Having first appeared at court in 1905, the former horse thief gradually began to enjoy the unlimited trust of the royal couple. Possessing certain hypnosis skills, Rasputin could help improve the well-being of Tsarevich Alexei, who was terminally ill with hemophilia. Believing in the healing power of the prayers of the “man of God,” the Empress invariably defended Rasputin, whose drunken brawls became known throughout the country. “The Elder,” despite his dark past, scandalous lifestyle and complete illiteracy, became one of the “centers of power” in the ruling elite, especially during the First World War, and had a direct influence on the adoption of the most important government decisions.

In the first years of the reign Nicholas II, there were no significant changes in the management system of the outskirts; the previous structure of institutions and administrative-territorial division were basically preserved. Since the late 90s, the tsarist government began to restrict the autonomy of the Grand Duchy of Finland. Appointed in 1898 by the Finnish Governor-General N.I. Bobrinsky presented the emperor with a note outlining a program that provided for the restriction of the rights of the Sejm, the introduction of the Russian language in office work, the abolition of customs and the Finnish mark, the unification of the army, etc., and began to consistently implement it. Activities of N.I. Bobrinsky contributed greatly to the rise of the social and revolutionary movement in Finland.

On November 1, 1894, according to the old style, the new - and last - Russian Emperor, Nicholas II, arrives in St. Petersburg. He enters the capital on a funeral train, on which the coffin with the body of his father, Emperor Alexander III, arrives in the city.

Alexander III died a little more than two weeks earlier, on October 20, old style (November 1, new style) in the Livadia Palace in Crimea, surrounded by his wife, Empress Maria Feodorovna, and his son, Grand Duke Nikolai Alexandrovich, who was destined to accept the imperial crown from his father. The Grand Duke was 26 years old at that time. In the next three weeks, he was to become the head of the Russian Empire and marry his bride - Princess of Hesse-Darmstadt, future Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. Or, as Nicholas II himself called his wife, “dear Alix.”

A year and a half later, in May 1896, his coronation will take place, at the same time, during the coronation celebrations, about 1.3 thousand people will die in a stampede on Khodynskoye Field in Moscow - many will consider this a bad omen. But in the fall of 1894, Nicholas II was torn between the happiness of his young husband, sadness for his departed father, and the imperial responsibilities that had fallen on his shoulders.

What the last Russian emperor felt and thought about in the first days of his reign - in a selection of his diaries compiled by Izvestia.

“We’ve finally entered winter”

October 20, 1894, day of death of Alexander III: « My God, my God, what a day! The Lord called back our adored, dear, beloved Pope. My head is spinning, I don’t want to believe it - the terrible reality seems so implausible. We spent the whole morning upstairs next to him!<…>Lord, help us in these difficult days! Poor dear Mom!.. In the evening at 9 1/2 there was a funeral service - in the same bedroom! I felt like I was dead.”

Soon after this, the imperial train leaves Crimea and heads to St. Petersburg, passing Moscow along the way, where a memorial service for Alexander III is being held in the Archangel Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin. Nicholas II carefully documents the trip, making short notes (he records the weather, worries about the condition of his mother, Empress Maria Feodorovna, and awaits upcoming official speeches with some apprehension). Nicholas II and the rest of the imperial family change trains on the funeral train only at the entrance to the capitals.

October 29, 1894: « We have finally entered winter. We stayed three times: in Kursk, Orel and Tula. For me, the presence of my dear beloved Alix on the train is a huge comfort and support! I sat with her all day.”

October 30, 1894 the young emperor arrives in Moscow: “How many bright memories there are here in the Kremlin - and how hard it is now for me to do everything instead of dear Papa! I read, took meals and sat between classes with my dear Alix. We had dinner at 8 o’clock and went to bed early.”

“I had to talk again”

On November 1, the funeral train with the body of the deceased arrives in St. Petersburg - and Nicholas II finally assumes the role of ruler of the empire.

November 1, 1894:“We moved to the station. Obukhovo on the funeral train and at 10 o'clock. arrived in St. Petersburg. A bitter meeting with the rest of the relatives. The procession from the station to the fortress lasted 4 hours, thanks to the fact that the bridges on the Neva were raised. The weather was gray - it was melting. After the funeral service we arrived at Anichkov [palace].”

Until now, his main support was meetings with his bride, the future Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, but here, in St. Petersburg, they are becoming more and more fragmentary: representatives of the monarchical houses of Europe begin to gather in the capital for mourning events, Nicholas II himself is gradually starting to perform their imperial duties. He tries to combine all this with his usual sports activities.

November 2, 1894: « I slept well; but as soon as you come to your senses, immediately the terrible oppression and heavy consciousness of what has happened return to your soul with new strength! Poor Mom felt weak again, and during the day she had a slight fainting spell. At 10.25 D. Willie arrived with Georgie; the whole family met them, as well as a guard of honor from the Izmailovsky regiment. I brought him to Anichkov. At 12 o'clock received the State. The Council in full force - I had to speak again! Dear Alix arrived for breakfast; It’s sad to see her only in fits and starts!<...>. I ran around the garden three times...”

Nicholas II still carefully records almost every day (reports, meetings of foreign guests, visits), but every day he complains more and more persistently about rare meetings with his bride.

November 3, 1894:“I read reports in the morning. At 11 o'clock I went to the station from the village of Bertie to meet the villages of Alfred, Erni, Jorzhi and Irene. Alix and Ella also met their own. Accepted N.X. Bunge. We had breakfast alone, because... Mom ate with Comrade Alix. At 1 1/2 I went with Misha to the fortress, then visited foreign princes. At 3 1/2 I received the entire retinue, again I had to say a few words.<..>It’s boring that we see Alix so little, I wish I could get married as soon as possible - then there’ll be no more goodbyes!”

“The little Neapolitan prince arrived in the evening”

Preparations for the wedding, as well as the subsequent honeymoon, take place for the emperor in an atmosphere of mourning celebrations.

November 6, 1894: « Sad day of the Hussar holiday. At 11 o'clock We went to mass in the fortress. The Serbian King arrived there straight from the station. We had breakfast at one o'clock at home. Then he received a lot of delegations: four German, two Austrian, Danish and Belgian - I had to talk to everyone! I walked a little in the garden, my head was spinning. The Serbian king visited me, then Ferdinand of Romania - they took away from me those few free minutes of the day in which I am allowed to see Alix. She drank tea with Ernie. At 7 1/2 I went to Zimny for Ksenia and took her to the fortress for a memorial service. We had dinner at 9 o'clock. In the evening the little Neapolitan prince arrived. My dear darling Alix was sitting with me.”

November 7, 1894:“For the second time we had to go through those hours of grief and sadness that befell us on October 20th. At 10 1/2 the bishop's service began and then the funeral service and funeral of the dear unforgettable Pope! It’s hard and painful to put such words here - it still seems that we are all in some kind of sleepy state and what suddenly! he will appear between us again!”

November 8, 1894: «<…>Two of the princes had already left: it would have been more likely that the rest would have been carried away as well. It’s easier to work when there are no strangers around, whose presence only increases the burden on me!”

By this time, the burden of state power was really beginning to weigh on the shoulders of the young emperor, who, moreover, had just buried his father.

November 9, 1894: «<…>Received various foreigners with and without letters. You have to answer all sorts of questions - so you get completely lost and confused! I took a walk in the garden. My Alix came to me at 4 o'clock. We drank tea upstairs. At 7 o'clock. gathered in the Malachite [hall].”

“I was choosing curtains, I was pretty tired”

At the same time, along with state affairs, the emperor is also engaged in arranging family housing in anticipation of the upcoming wedding.

November 10, 1894:“I woke up at 7 o’clock and, after drinking coffee, went to get some fresh air. It was cold and it was snowing. I read until 10 o'clock. After a joint breakfast, I received and had reports from Durnovo, Richter and Vorontsov. We had breakfast at one o'clock. Again I received until 3 1/4. After the walk, with Alix I chose carpets and curtains for two rooms, which will be added to my old ones , from Gosh - due to the fact that it would be too cramped for the two of us to fit in the 4 previous rooms! I’m pretty tired of this day.”

November 11, 1894: « In the morning I walked in the garden. It was terrible darkness all day. After breakfast, he had reports: Witte and Krivoshein. Then he received the second series of governors-general and commanders of troops. We had breakfast with Mama, Apapa and Jorji (Greek), since the rest had all left. Received by the entire Senate in full force ballroom. Walked and rode a bicycle in the garden."

November 12, 1894:“Quite a tiring day: at 10 o’clock in the morning the reports began - Den, Count Vorontsov, D. Alexei and Chikhachev, and then all the Kazakh atamans introduced themselves. troops. Had breakfast with Mama, Apapa and Comrade Alix. At 3 o'clock I received it in the Winter Palace. a lot of delegations from all over Russia - up to 460 people, all at once in the Nikolaev Hall."

"My Wedding Day"

The long-awaited wedding of Nicholas II and Alexandra Fedorovna (by this time she had already received Orthodox baptism) takes place extremely modestly and in an atmosphere of deep mourning - they are married in the Great Church of the Winter Palace. But Nicholas II is happy.

November 14, 1894: « My wedding day! After general coffee, we went to get dressed: I put on my hussar uniform and at 11 1/2 I went with Misha to the Winter Palace. Troops were stationed all over Nevsky for Mama and Alix to pass. While her toilet was taking place in Malachite, we all waited in the Arab room. At 10 min. The first one began to go to a large church, from where I returned as a married man! My best men were: Misha, Georgie, Kirill and Sergey. In Malakhitova we were presented with a huge silver swan from the family. Having changed clothes, Alix got into a carriage with a Russian harness with a postilion with me, and we went to the Kazan Cathedral. There were a ton of people on the streets - they could barely get through! Upon arrival in Anichkov, I was greeted in the courtyard with honor and punishment. from her L.Tv. Ulansky village. Mom was waiting with bread and salt in our rooms. We sat all evening and answered telegrams. We had dinner at 8 o'clock. We went to bed early because... She had a bad headache!”

"Three workers lifted the heavy grate"

23 years later, in March 1917, Nicholas II would abdicate the throne - for himself and for his son and direct heir, Tsarevich Alexei. “In the name of the good and salvation of Russia,” he will explain his decision to representatives of the Provisional Committee of the State Duma A.I., who came to him from revolutionary Petrograd. Guchkov and V.V. Shulgin.

Nicholas II will continue to keep diaries even after abdicating the throne - during his exile in Tobolsk. The last entries in them were made shortly before the execution of the royal family, at the end of June 1918.

« June 28. Thursday. In the morning around 10 1/2 o'clock. Three workers approached the open window, lifted a heavy grill and attached it to the outside of the frame - without warning from Yu (Yurovsky - commandant of the Ipatiev House, where the imperial family was kept - Izvestia). We like this guy less and less! I started reading Volume VIII of Saltykov [-Shchedrin],” says one of the last diary entries.

On the night of July 17, “Citizen Romanov”, Alexandra Fedorovna and their children were shot. Along with them, Doctor Botkin and three members of the servants who remained with the imperial family died.

Years of life: 1868-1818

Reign: 1894-1917

Born May 6 (19 old style) 1868 in Tsarskoe Selo. Russian emperor who reigned from October 21 (November 2), 1894 to March 2 (March 15), 1917. Belonged to the Romanov dynasty, was the son and successor.

From birth he had the title - His Imperial Highness the Grand Duke. In 1881, he received the title of Heir to Tsarevich, after the death of his grandfather, Emperor.

Title of Emperor Nicholas 2

Full title of the emperor from 1894 to 1917: “By God's favor, We, Nicholas II (Church Slavonic form in some manifestos - Nicholas II), Emperor and Autocrat of All Russia, Moscow, Kiev, Vladimir, Novgorod; Tsar of Kazan, Tsar of Astrakhan, Tsar of Poland, Tsar of Siberia, Tsar of Chersonese Tauride, Tsar of Georgia; Sovereign of Pskov and Grand Duke of Smolensk, Lithuania, Volyn, Podolsk and Finland; Prince of Estland, Livonia, Courland and Semigal, Samogit, Bialystok, Korel, Tver, Yugorsk, Perm, Vyatka, Bulgarian and others; Sovereign and Grand Duke of Novagorod of the Nizovsky lands, Chernigov, Ryazan, Polotsk, Rostov, Yaroslavl, Belozersky, Udorsky, Obdorsky, Kondiysky, Vitebsk, Mstislavsky and all northern countries Sovereign; and Sovereign of Iversk, Kartalinsky and Kabardian lands and regions of Armenia; Cherkasy and Mountain Princes and other Hereditary Sovereign and Possessor, Sovereign of Turkestan; Heir of Norway, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein, Stormarn, Ditmarsen and Oldenburg, and so on, and so on, and so on.”

The peak of Russia's economic development and at the same time growth  revolutionary movement, which resulted in the revolutions of 1905-1907 and 1917, fell precisely on years of reign of Nicholas 2. Foreign policy at that time was aimed at Russia's participation in blocs of European powers, the contradictions that arose between them became one of the reasons for the outbreak of the war with Japan and World War I.

revolutionary movement, which resulted in the revolutions of 1905-1907 and 1917, fell precisely on years of reign of Nicholas 2. Foreign policy at that time was aimed at Russia's participation in blocs of European powers, the contradictions that arose between them became one of the reasons for the outbreak of the war with Japan and World War I.

After the events of the February Revolution of 1917, Nicholas II abdicated the throne, and a period of civil war soon began in Russia. The Provisional Government sent him to Siberia, then to the Urals. Together with his family, he was shot in Yekaterinburg in 1918.

Contemporaries and historians characterize the personality of the last king contradictory; Most of them believed that his strategic abilities in the conduct of public affairs were not successful enough to change the political situation at that time for the better.

After the revolution of 1917, he began to be called Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov (before that, the surname “Romanov” was not indicated by members of the imperial family, the titles indicated the family affiliation: emperor, empress, grand duke, crown prince).

With the nickname Bloody, which the opposition gave him, he appeared in Soviet historiography.

Biography of Nicholas 2

He was the eldest son of Empress Maria Feodorovna and Emperor Alexander III.

In 1885-1890 received his home education as part of a gymnasium course under a special program that combined the course of the Academy of the General Staff and the Faculty of Law of the University. Training and education took place under the personal supervision of Alexander the Third with a traditional religious basis.

Most often he lived with his family in the Alexander Palace. And he preferred to relax in the Livadia Palace in Crimea. For annual trips to the Baltic and Finnish Seas he had at his disposal the yacht “Standart”.

At the age of 9 he began keeping a diary. The archive contains 50 thick notebooks for the years 1882-1918. Some of them have been published.

He was interested in photography and liked watching movies. I read both serious works, especially on historical topics, and entertaining literature. I smoked cigarettes with tobacco specially grown in Turkey (a gift from the Turkish Sultan).

On November 14, 1894, a significant event took place in the life of the heir to the throne - the marriage with the German Princess Alice of Hesse, who after the baptismal ceremony took the name Alexandra Fedorovna. They had 4 daughters - Olga (November 3, 1895), Tatyana (May 29, 1897), Maria (June 14, 1899) and Anastasia (June 5, 1901). And the long-awaited fifth child on July 30 (August 12), 1904, became the only son - Tsarevich Alexei.

Coronation of Nicholas 2

On May 14 (26), 1896, the coronation of the new emperor took place. In 1896 he  traveled around Europe, where he met with Queen Victoria (his wife's grandmother), William II, and Franz Joseph. The final stage of the trip was a visit to the capital of the allied France.

traveled around Europe, where he met with Queen Victoria (his wife's grandmother), William II, and Franz Joseph. The final stage of the trip was a visit to the capital of the allied France.

His first personnel changes were the dismissal of the Governor-General of the Kingdom of Poland, Gurko I.V. and the appointment of A.B. Lobanov-Rostovsky as Minister of Foreign Affairs.

And the first major international action was the so-called Triple Intervention.

Having made huge concessions to the opposition at the beginning of the Russo-Japanese War, Nicholas II attempted to unite Russian society against external enemies. In the summer of 1916, after the situation at the front had stabilized, the Duma opposition united with the general conspirators and decided to take advantage of the created situation to overthrow the tsar.

They even named the date February 12-13, 1917, as the day the emperor abdicated the throne. It was said that a “great act” would take place - the sovereign would abdicate the throne, and the heir, Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich, would be appointed as the future emperor, and Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich would become the regent.

In Petrograd, on February 23, 1917, a strike began, which became general three days later. On the morning of February 27, 1917, soldier uprisings took place in Petrograd and Moscow, as well as their unification with the strikers.

The situation became tense after the announcement of the emperor's manifesto on February 25, 1917 to terminate the meeting of the State Duma.

On February 26, 1917, the Tsar gave an order to General Khabalov “to stop the unrest, which is unacceptable in difficult times of war.” General N.I. Ivanov was sent on February 27 to Petrograd to suppress the uprising.

On the evening of February 28, he headed to Tsarskoe Selo, but was unable to get through and, due to the loss of contact with Headquarters, he arrived in Pskov on March 1, where the headquarters of the armies of the Northern Front under the leadership of General Ruzsky was located.

Abdication of Nicholas 2 from the throne

At about three o'clock in the afternoon, the emperor decided to abdicate the throne in favor of the crown prince during the regency of Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich, and in the evening of the same day he announced to V.V. Shulgin and A.I. Guchkov about the decision to abdicate the throne for his son. March 2, 1917 at 11:40 p.m. he handed over to Guchkov A.I. Manifesto of renunciation, where he wrote: “We command our brother to rule over the affairs of the state in complete and inviolable unity with the representatives of the people.”

Nicholas 2 and his relatives lived under arrest in the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo from March 9 to August 14, 1917.

In connection with the strengthening of the revolutionary movement in Petrograd, the Provisional Government decided to transfer the royal prisoners deep into Russia, fearing for their lives. After much debate, Tobolsk was chosen as the city of settlement for the former emperor and his relatives. They were allowed to take personal belongings and necessary furniture with them and offer service personnel to voluntarily accompany them to the place of their new settlement.

On the eve of his departure, A.F. Kerensky (head of the Provisional Government) brought the brother of the former tsar, Mikhail Alexandrovich. Mikhail was soon exiled to Perm and on the night of June 13, 1918 he was killed by the Bolshevik authorities.

On August 14, 1917, a train departed from Tsarskoe Selo under the sign “Japanese Red Cross Mission” with members of the former imperial family. He was accompanied by a second squad, which included guards (7 officers, 337 soldiers).

The trains arrived in Tyumen on August 17, 1917, after which those arrested were taken to Tobolsk on three ships. The Romanovs were accommodated in the governor's house, specially renovated for their arrival. They were allowed to attend services at the local Church of the Annunciation. The protection regime for the Romanov family in Tobolsk was much easier than in Tsarskoe Selo. They led a measured, calm life.

Permission from the Presidium of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the fourth convocation to transfer Romanov and his family members to Moscow for the purpose of trial was received in April 1918.

On April 22, 1918, a column with machine guns of 150 people left Tobolsk for Tyumen. On April 30, the train arrived in Yekaterinburg from Tyumen. To house the Romanovs, a house that belonged to mining engineer Ipatiev was requisitioned. The service staff also lived in the same house: cook Kharitonov, doctor Botkin, room girl Demidova, footman Trupp and cook Sednev.

The fate of Nicholas 2 and his family

To resolve the issue of the future fate of the imperial family, at the beginning of July 1918, military commissar F. Goloshchekin urgently left for Moscow. The All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars authorized the execution of all the Romanovs. After this, on July 12, 1918, based on the decision made, the Ural Council of Workers', Peasants' and Soldiers' Deputies at a meeting decided to execute the royal family.

On the night of July 16-17, 1918 in Yekaterinburg, in the Ipatiev mansion, the so-called “House of Special Purpose,” the former Emperor of Russia, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, their children, Doctor Botkin and three servants (except for the cook) were shot.

The Romanovs' personal property was plundered.

All members of his family were canonized by the Catacomb Church in 1928.

In 1981, the last Tsar of Russia was canonized by the Orthodox Church abroad, and in Russia the Orthodox Church canonized him as a passion-bearer only 19 years later, in 2000.

In accordance with the decision of August 20, 2000 of the Council of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church, the last Emperor of Russia, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, princesses Maria, Anastasia, Olga, Tatiana, Tsarevich Alexei were canonized as holy new martyrs and confessors of Russia, revealed and unmanifested.

This decision was received ambiguously by society and was criticized. Some opponents of canonization believe that attribution Tsar Nicholas 2 sainthood is most likely of a political nature.

The result of all the events related to the fate of the former royal family was the appeal of Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna Romanova, head of the Russian Imperial House in Madrid, to the Prosecutor General's Office of the Russian Federation in December 2005, demanding the rehabilitation of the royal family, executed in 1918.

On October 1, 2008, the Presidium of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation (Russian Federation) decided to recognize the last Russian emperor and members of the royal family as victims of illegal political repression and rehabilitated them.

Nicholas II Alexandrovich (born - May 6 (18), 1868, death - July 17, 1918, Yekaterinburg) - Emperor of All Russia, from the imperial house of Romanov.

Childhood

The heir to the Russian throne, Grand Duke Nikolai Alexandrovich, grew up in the atmosphere of a luxurious imperial court, but in a strict and, one might say, Spartan environment. His father, Emperor Alexander III, and mother, Danish princess Dagmara (Empress Maria Feodorovna) fundamentally did not allow any weaknesses or sentimentality in raising children. A strict daily routine was always established for them, with mandatory daily lessons, visits to church services, mandatory visits to relatives, and mandatory participation in many official ceremonies. The children slept on simple soldier's beds with hard pillows, took cold baths in the mornings and were given oatmeal for breakfast.

The youth of the future emperor

1887 - Nikolai was promoted to staff captain and assigned to the Life Guards of the Preobrazhensky Regiment. There he was listed for two years, first performing the duties of a platoon commander and then a company commander. Then, to join the cavalry service, his father transferred him to the Life Guards Hussar Regiment, where Nikolai took command of the squadron.

Thanks to his modesty and simplicity, the prince was quite popular among his fellow officers. 1890 - his training was completed. The father did not burden the heir to the throne with state affairs. He appeared from time to time at meetings of the State Council, but his gaze was constantly directed at his watch. Like all guard officers, Nikolai devoted a lot of time to social life, often visited the theater: he adored opera and ballet.

Nicholas and Alice of Hesse

Nicholas II in childhood and youth

Apparently women also occupied him. But it is interesting that Nikolai experienced his first serious feelings for Princess Alice of Hesse, who later became his wife. They first met in 1884 in St. Petersburg at the wedding of Ella of Hesse (Alice's older sister) with Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich. She was 12 years old, he was 16. 1889 - Alix spent 6 weeks in St. Petersburg.

Later, Nikolai wrote: “I dream of someday marrying Alix G. I have loved her for a long time, but especially deeply and strongly since 1889... All this long time I did not believe my feeling, did not believe that my cherished dream could come true.”

In reality, the heir had to overcome many obstacles. Parents offered Nicholas other parties, but he resolutely refused to associate himself with any other princess.

Ascension to the throne

1894, spring - Alexander III and Maria Fedorovna were forced to give in to their son’s wishes. Preparations for the wedding have begun. But before it could be played, Alexander III died on October 20, 1894. For no one was the death of an emperor more significant than for the 26-year-old young man who inherited his throne.

“I saw tears in his eyes,” recalled Grand Duke Alexander. “He took me by the arm and led me downstairs to his room. We hugged and both cried. He couldn't gather his thoughts. He knew that he had now become an emperor, and the severity of this terrible event struck him down... “Sandro, what should I do? - he exclaimed pathetically. - What is going to happen to me, to you... to Alix, to my mother, to all of Russia? I'm not ready to be a king. I never wanted to be him. I don't understand anything about board affairs. I don’t even have a clue how to talk to ministers.’”

The next day, when the palace was draped in black, Alix converted to Orthodoxy and from that day began to be called Grand Duchess Alexandra Feodorovna. On November 7, the solemn burial of the late emperor took place in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg, and a week later the wedding of Nicholas and Alexandra took place. On the occasion of mourning there was no ceremonial reception or honeymoon.

Personal life and royal family

1895, spring - Nicholas II moved his wife to Tsarskoe Selo. They settled in the Alexander Palace, which remained the main home of the imperial couple for 22 years. Everything here was arranged according to their tastes and desires, and therefore Tsarskoye always remained their favorite place. Nikolai usually got up at 7, had breakfast and disappeared into his office to start work.

By nature, he was a loner and preferred to do everything himself. At 11 o'clock the king interrupted his classes and went for a walk in the park. When children appeared, they invariably accompanied him on these walks. Lunch in the middle of the day was a formal ceremonial occasion. Although the Empress was usually absent, the Emperor dined with his daughters and members of his retinue. The meal began, according to Russian custom, with prayer.

Neither Nikolai nor Alexandra liked expensive, complex dishes. He received great pleasure from borscht, porridge, and boiled fish with vegetables. But the king’s favorite dish was roasted young pig with horseradish, which he washed down with port wine. After lunch, Nikolai took a horseback ride along the surrounding rural roads in the direction of Krasnoe Selo. At 4 o'clock the family gathered for tea. According to etiquette, introduced back in the day, only crackers, butter and English biscuits were served with tea. Cakes and sweets were not allowed. Sipping tea, Nikolai quickly looked through newspapers and telegrams. Afterwards he returned to his work, receiving a stream of visitors between 5 and 8 p.m.

At exactly 20 o'clock all official meetings ended, and Nicholas II could go to dinner. In the evening, the emperor often sat in the family living room, reading aloud, while his wife and daughters worked on needlework. According to his choice, it could be Tolstoy, Turgenev or his favorite writer Gogol. However, there could have been some kind of fashionable romance. The sovereign's personal librarian selected for him 20 of the best books a month from all over the world. Sometimes, instead of reading, the family spent evenings pasting photographs taken by the court photographer or themselves into green leather albums embossed with the royal monogram in gold.

Nicholas II with his wife

The end of the day came at 11 pm with the serving of evening tea. Before leaving, the emperor wrote notes in his diary, and then took a bath, went to bed and usually immediately fell asleep. It is noted that, unlike many families of European monarchs, the Russian imperial couple had a common bed.

1904, July 30 (August 12) - the 5th child was born in the imperial family. To the great joy of the parents it was a boy. The king wrote in his diary: “A great, unforgettable day for us, on which the mercy of God so clearly visited us. At 1 o’clock in the afternoon Alix gave birth to a son, who was named Alexei during prayer.”

On the occasion of the appearance of the heir, guns were fired throughout Russia, bells rang and flags fluttered. However, a few weeks later, the imperial couple was shocked by the terrible news - it turned out that their son had hemophilia. The following years passed in a difficult struggle for the life and health of the heir. Any bleeding, any injection could lead to death. The torment of their beloved son tore the hearts of the parents. Alexei's illness had a particularly painful effect on the empress, who over the years began to suffer from hysteria, she became suspicious and extremely religious.

Reign of Nicholas II

Meanwhile, Russia was going through one of the most turbulent stages of its history. After the Japanese War, the first revolution began, suppressed with great difficulty. Nicholas II had to agree to the establishment of the State Duma. The next 7 years were lived in peace and even relative prosperity.

Promoted by the emperor, Stolypin began to carry out his reforms. At one time it seemed that Russia would be able to avoid new social upheavals, but the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 made the revolution inevitable. The crushing defeats of the Russian army in the spring and summer of 1915 forced Nicholas 2 to lead the troops himself.

From that time on, he was on duty in Mogilev and could not delve deeply into state affairs. Alexandra began to help her husband with great zeal, but it seems that she harmed him more than she actually helped. Both senior officials, grand dukes, and foreign diplomats felt the approach of revolution. They tried as best they could to warn the emperor. Repeatedly during these months, Nicholas II was offered to remove Alexandra from affairs and create a government in which the people and the Duma would have confidence. But all these attempts were unsuccessful. The Emperor gave his word, despite everything, to preserve autocracy in Russia and transfer it whole and unshakable to his son; Now, when pressure was put on him from all sides, he remained faithful to his oath.

Revolution. Abdication

1917, February 22 - without making a decision on the new government, Nicholas II went to Headquarters. Immediately after his departure, unrest began in Petrograd. On February 27, the alarmed emperor decided to return to the capital. On the way, at one of the stations, he accidentally learned that a temporary committee of the State Duma, headed by Rodzianko, was already operating in Petrograd. Then, after consulting with the generals of his retinue, Nikolai decided to make his way to Pskov. Here, on March 1, from the commander of the Northern Front, General Ruzsky, Nikolai learned the latest amazing news: the entire garrison of Petrograd and Tsarskoe Selo went over to the side of the revolution.

His example was followed by the Guard, the Cossack convoy and the Guards crew with Grand Duke Kirill at their head. The negotiations with the front commanders, undertaken by telegraph, finally defeated the tsar. All the generals were merciless and unanimous: it was no longer possible to stop the revolution by force; In order to avoid civil war and bloodshed, Emperor Nicholas 2 must abdicate the throne. After painful hesitation, late in the evening of March 2, Nicholas signed his abdication.

Arrest

Nicholas 2 with his wife and children

The next day, he gave the order for his train to go to Headquarters, to Mogilev, as he wanted to say goodbye to the army one last time. Here, on March 8, the emperor was arrested and taken under escort to Tsarskoye Selo. From that day on, a time of constant humiliation began for him. The guard behaved defiantly rudely. It was even more offensive to see the betrayal of those people who were used to being considered the closest. Almost all the servants and most of the ladies-in-waiting abandoned the palace and the empress. Doctor Ostrogradsky refused to go to the sick Alexei, saying that he “finds the road too dirty” for further visits.

Meanwhile, the situation in the country began to deteriorate again. Kerensky, who by that time had become the head of the Provisional Government, decided that for security reasons the royal family should be sent away from the capital. After much hesitation, he gave the order to transport the Romanovs to Tobolsk. The move took place in early August in deep secrecy.

The royal family lived in Tobolsk for 8 months. Her financial situation was very cramped. Alexandra wrote to Anna Vyrubova: “I am knitting socks for little (Alexey). He requires a couple more, since all of his are in holes... I'm doing everything now. Dad’s (the king’s) pants were torn and needed mending, and the girls’ underwear was in rags... I became completely grey...” After the October coup, the situation for the prisoners became even worse.

1918, April - the Romanov family was transported to Yekaterinburg, they were settled in the house of the merchant Ipatiev, which was destined to become their last prison. 12 people lived in the 5 upper rooms of the 2nd floor. Nicholas, Alexandra and Alexey lived in the first, and the Grand Duchesses lived in the second. The rest was divided among the servants. In the new place, the former emperor and his relatives felt like real prisoners. Behind the fence and on the street there was an external guard of Red Guards. There were always several people with revolvers in the house.

This internal guard was selected from among the most reliable Bolsheviks and was very hostile. It was commanded by Alexander Avdeev, who called the emperor nothing more than “Nicholas the Bloody.” None of the members of the royal family could have privacy, and even to the toilet the grand duchesses walked accompanied by one of the guards. For breakfast, only black bread and tea were served. Lunch consisted of soup and cutlets. The guards often took pieces from the pan with their hands in front of the diners. The prisoners' clothes were completely shabby.

On July 4, the Ural Soviet removed Avdeev and his people. They were replaced by 10 security officers led by Yurovsky. Despite the fact that he was much more polite than Avdeev, Nikolai felt the threat emanating from him from the first days. In fact, the clouds were gathering over the family of the last Russian emperor. At the end of May, a Czechoslovak rebellion broke out in Siberia, the Urals and the Volga region. The Czechs launched a successful attack on Yekaterinburg. On July 12, the Ural Council received permission from Moscow to decide for itself the fate of the deposed dynasty. The Council decided to shoot all the Romanovs and entrusted the execution to Yurovsky. Later, the White Guards were able to capture several participants in the execution and, from their words, reconstruct in all details the picture of the execution.

Execution of the Romanov family