Sole. Flag - ship banner Naval pennants meaning

Naval code of signals is a set of signal flags, used along with the semaphore alphabet in the USSR Navy to transmit information (signals, orders) between ships and coastal services. Set of naval signals... ... Wikipedia

Signal flags hoisted on ships on holidays; they are raised on specially mounted halyards, usually running from the stem to the foremast quarter, then to the mainmast quarter and further to the sternpost. From the stem to the fore-mast, the masts are formed... ...Nautical Dictionary

Coloring flags,- flags of the USSR Naval Code of Signals, hoisted on ships and vessels of the Navy on special occasions. On ships of the USSR navy as a F. r. flags of the International Code of Signals are used... Glossary of military terms

Signal flags: At sea: Flags of the international code of signals For divers: Diving flag In auto racing: Racing flags ... Wikipedia

- (The International Code of Signals; INTERCO) is intended for communication in various ways and means in order to ensure the safety of navigation and the protection of human life at sea, especially in cases where language difficulties arise... ... Wikipedia

St. Andrew's flag Marine flag is a distinctive sign in the form of a panel of regular geometric shape with a special color that can be identified ... Wikipedia

This article should be Wikified. Please format it according to the rules for formatting articles... Wikipedia

Not to be confused with the International Phonetic Alphabet. The phonetic alphabet is a standardized (for a given language and/or organization) way of reading the letters of the alphabet. It is used in radio communications when transmitting spellings that are difficult to understand... Wikipedia

The "IPA" request is redirected here. See also other meanings. "MFA" query redirects here. See also other meanings. Not to be confused with the term "NATO Phonetic Alphabet". International Phonetic Alphabet Type Alphabet Languages... ... Wikipedia

The International Code of Signals (INTERCO) is intended for communication in various ways and means in order to ensure the safety of navigation and the protection of human life at sea, especially in cases where language communication difficulties arise. When compiling the Code, it was taken into account that the widespread use of radiotelephone and radiotelegraph allows, whenever there are no language difficulties, to carry out simple and effective communication in clear text.

The signals used in the Code consist of:

- single-letter signals intended for very urgent, important or frequently used messages;

- two-letter signals that make up the General Section;

- three-letter signals that make up the Medical Section and begin with the letter M.

Each signal of the Code has a complete semantic meaning. This principle runs throughout the Code; in some cases, digital additions are used to expand the meaning of the main signal.

People came to the idea of transmitting signals at sea using colored flags quite a long time ago. Initially, the meaning of the flag signal was determined only by the location of the flag, and any flags were used, including knightly standards.

The first attempts to regulate and unify flag signals date back only to the 17th century. In 1653, the first collection of flag signals was published in Great Britain.

The meaning of the signal depended not only on the type of flag, but also on the place where it was raised, as well as on its accompaniment by a certain combination of sails or gunfire.

In 1780 (Howe signal book) it was decided to leave only 10 signal flags. Each combination of flags had a specific meaning. A little later, in 1800, Captain Home Riggs Popham compiled the so-called. "Nautical Dictionary", in which more than 2000 flag signals were deciphered. In 1803, Popham's system was adopted by the Royal Navy.

But all this time, flag signals remained the prerogative of the military. Only at the beginning of the 19th century, through the efforts of Frederick Marryat, the Code of Signals for the Merchant Marine was compiled.

The system consisted of 15 flags and pennants. With its help it was possible to convey words and entire sentences. The system was used only by the British./p>

Over time, the need arose to put together a similar system for international use. In 1857, the "System of Code Signals for the Merchant Marine" of 18 flags was developed.

It has already been used in Britain, the USA, Canada, and France. In 1887, the "System of Code Signals for the Merchant Marine" was renamed the "International Code of Signals". All maritime states accepted this code.

It came into force on January 1, 1901. In 1931, an international commission from 8 countries modified the signaling system, making it more convenient. The last revision of the Code took place on April 1, 1969. Since then, the flags of the Code have also been deciphered in Cyrillic. Currently, the International Code of Signals contains 26 alphabetic flags, 10 digital and 3 substitute flags. To transmit a message, they find the corresponding text in the code of signals, write down the signal sections of the flags opposite it (there are one-, two-, three-flag signals, as well as four-flag signals, informing about the nationality of the vessel), type them from the signal flags and raise them on the halyards. The signalman on the receiving ship, having written down these combinations, finds their meanings in the signal codes. The flag signaling range with good visibility reaches 4-5 miles. Below are the meanings of signals from one flag, as well as the names of the flags and their correspondence to the letters of the Latin alphabet and Cyrillic alphabet.

Additional and special signals

Additional and special signals

First substitute

Second substitute

Third substitute

Fourth substitute

Replacement pennants

If a vessel has a single set of flags, replacement pennants allow the letter flag or number pennant to be repeated one or more times:

- the first replacement pennant always repeats the topmost signal flag of the first signal combination;

- the second replacement pennant always repeats the second;

- the third substitute is the third signal flag from the top.

A replacement pennant may never be used more than once in the same group.

Letter signals

Letter signals

A, Alfa, Alpha

I have a diver lowered, stay away from me and follow at low speed...

B, Bravo, Bravo

I am loading or unloading or have dangerous cargo on board.

C, Charlie, Charlie

Positive answer. The meaning of the previous group should be read in the affirmative form.

D, Delta, Delta

Stay away from me, I'm having a hard time managing.

E, Echo, Eco

I turn right.

F, Foxtrot, Foxtrot

I'm out of control, keep in touch with me.

G, Golf, Golf

I need a pilot.

H, Hotel, Hotel

I have a pilot on board.

I, India, India

I turn left.

J, Juliet

There is a fire and I have dangerous cargo on board, stay away from me

K, Kilo, Kilo

I want to connect with you.

Kilo signal with a number means I want to establish a connection:

K2 Morse signs using flags or hands;

K3 amplification device (megaphone);

K4 signaling device;

K5 sound alarm device;

K6 flags of the International Code of Signals;

K7 radiotelephone at 500 kHz;

K8 radiotelephone on a frequency of 2182 kHz;

K9 VHF radiotelephone on channel 16.

L, Lima, Lima

Stop your ship immediately.

M, Mike, Mike

My ship is stopped and has no movement relative to the water.

N, November, November

Negative answer. The value of the previous group must be read in negative form.

O, Oscar, Oska

Man overboard.

P, Papa, Dad

In the harbor: Everyone should be on board as the ship is leaving soon.

At sea: I need a pilot.

The Papa signal for fishing vessels operating in close proximity to each other means my nets are caught on an obstacle.

Q, Quebec, Cabec

My ship is uninfected, please give me free practice.

R, Romeo, Romeo

Accepted.

S, Sierra, Sierra

My thrusters are running in reverse.

T, Tango, Tangou

Stay away from me, I'm doing a pair trawling.

U, Uniform, Uniform

The course leads to danger.

V, Victor, Victa

I need help.

“The national flag of the country raised on a Navy ship is a symbol of state sovereignty, and the Navy flag is the battle flag of the ship,” we read in the Ship’s Charter. How was this wonderful and, perhaps, the most important naval tradition, legalized by the charter for a long time, born in the Russian Navy - raising and carrying the State and Naval flags, as well as a number of other flags?

On any ship of the Navy there is always a set of a wide variety of flags. Each of them climbs the mast under specific, precisely regulated circumstances and in clearly established places, having a strictly defined meaning. All these flags have not only their own shape and colors, but also, of course, their own history.

Ship flags appeared a very long time ago - their origin began in the very early stages of shipbuilding and navigation.

Frescoes and bas-reliefs of Ancient Egypt preserved for posterity the image of ship flags that existed back in the 14th-13th centuries. BC. Over the years, decorating ships with flags has become a tradition.

The ship banners of those distant times were panels of a wide variety of sizes, shapes, patterns and colors. In ancient times, they served as distinctive external signs, symbols of the economic power of the ship owner. The richer he was, the more luxuriously he decorated his ship with flags, the more expensive the fabric from which they were made. In the middle of the 14th century, for example, it was considered especially chic to raise a giant flag on a ship. For example, the Duke of Orleans (from 1498 to 1515 he was King Louis XII of France), who commanded the fleet in 1494, had a personal standard 25 meters long, made of yellow and red taffeta. On both sides of this flag, the Virgin Mary was depicted against a background of a silver cloud. Its painting was carried out by the court artist Burdinson. In 1520, on the flagship of the English king Henry VIII, pennants and flags (and sails) were embroidered in gold. There were a great many flags on ships of that time. Sometimes their number reached one and a half dozen. They were installed on masts, on stern, bow and even side flagpoles. Apparently, it was considered prestigious to hang expensive bright flags on all sides of the ship. But this was hardly convenient for the crew - the side flagpoles, for example, greatly interfered with the control of the sails, and numerous large flags created additional, unwanted, and even dangerous, windage. Apparently, that’s why over time, only three places were allocated for them on the ship: bow, stern and masts. Here they began to raise flags, by which during battles the crews distinguished their ships from others, as well as the location of the admirals-commanders of squadrons or flagships who had their own personal flag.

With the development of means of armed warfare at sea, flags, admiral's, captain's flags appeared, and later flags denoting the vanguard, corps de battalion and rearguard (parts of the battle formation in which the ships fought). Special flags marked the presence of a significant official on board.

For a long time, the crew also had signal flags, each of which had a letter or special semantic meaning. With a set of two, three or four signal flags raised at the end of the yard, almost any order, command or message could be transmitted in encrypted form, regardless of the language the correspondents spoke.

Today, as a rule, most signal flags are rectangular in shape, but there are also triangular flags, as well as long narrow flags with two pointed “braids”.

Nowadays, most ship flags are sewn from special lightweight woolen material - the so-called spirit flag.

With the formation of sovereign national states, national flags also appeared, and ships leaving the borders of their state were required to have a flag by which the “nationality” of the ship was determined. When regular military fleets appeared, the flag began to distinguish not only the nationality, but also the purpose of the ship - military or commercial.

As in other countries, ship flags appeared in Russia long before the formation of a centralized state. Ancient Greek chroniclers noted that even during the sea campaigns of the Eastern Slavs to Constantinople, the Russian boats, as a rule, had two flags: one rectangular and the other with a corner cut out on the outside, that is, with braids. Such flags later became an indispensable accessory of the “gulls” and plows, on which the Zaporozhye and Don Cossacks made brave sea voyages across the Black Sea to Sinop, Bosphorus, Trebizond and other Turkish cities.

And yet, the true beginning of the history of the Russian naval flag should be associated with the construction of the first Russian warship “Eagle”.

“Eagle” was launched in 1668. When work on the construction of the ship was coming to an end, the Dutch engineer O. Butler, under whose leadership the work on the slipway was going on, turned to the Boyar Duma with the request: “...to ask His Royal Majesty for an order: what, as is the custom of other states, to raise the flag on the ship.” The palace order responded that in practice such a circumstance had not happened, and the Armory Chamber “builds banners, banners and ensigns for military units and governors, but what about the ship’s banner. The king ordered to ask him, Butler, what the custom is for this in his country.” Butler replied that in their country they take kindyak material - scarlet, white and blue, sew it in stripes and such a flag serves them to designate their Dutch nationality. Then, in consultation with the Boyar Duma, the tsar ordered the new ship “Eagle” to raise a white-blue-red flag with a double-headed eagle sewn on it. Prince Alexander Putyatin in his article “On the Russian National Flag” writes that this was the first Russian national flag. However, some researchers are inclined to consider the appearance of the first ship flag of Russia not only the first national maritime flag, but also the first ship standard. How did the concept of “standard” come into being?

Around the first quarter of the 16th century. In the heavy noble cavalry of Western European armies, a square, sometimes triangular flag appeared with a smaller panel than a regular banner. This flag began to be called the standard . The shaft of the standard had a special device made of straps for securely holding it by the rider and attaching it to the stirrup. The standard in a cavalry company (squadron) was carried by a specially appointed cornet officer. Each standard had a special color and design and served to indicate the gathering place and location of a particular cavalry unit. Around the same time, the standard appeared in the fleets as the flag of the head of state (emperor, king), hoisted on the mainmast of the ship if the specified persons were on board. At first, in order to emphasize the greatness and power of the monarchs, standards were made of expensive brocade fabrics, embroidered with gold and silver, and decorated with precious stones. In the middle of the 16th century. State emblems appear on the standards, symbolizing state power.

Presumably in 1699, Peter I legitimized a new royal standard - a yellow rectangular panel with a black double-headed eagle in the middle and with white maps of the Caspian, Azov and White Seas in the keys and in one of the paws. When our troops captured the Nyenschanz fortress and the path to the Baltic Sea was opened, a map of the Baltic Sea appeared on the royal standard.

Where did the double-headed eagle come from to Russia and then appear on the standard? Prince Putyatin, in the work we have already cited, explains the origin and history of the State Emblem in the form of a double-headed eagle.

“Russia of ancient times did not know the science of heraldry,” writes the author, “ brilliantly developed in the West in the Middle Ages. But symbolic, generic and personal signs have been known in Rus' for a long time. Since the time of Ivan Kalita, the state seal has been an image of a horseman with a spear, often accompanied by the inscription: “The Great Prince with a spear in his hand.” After the Battle of Kulikovo, a serpent began to be depicted under the horseman as a symbol of the prince’s “defeat of the Basurman power.”

In 1472, a significant event took place in the history of Rus' - the marriage of the Grand Duke of Moscow Ivan III with Sophia Paleologus, the niece of the last emperor of Byzantium, Constantine XI. This contributed to the proclamation of the Russian state as the successor to the Byzantine Empire. As a right of succession to the throne, the coat of arms of Byzantium came to Russia - the double-headed eagle. It is known that since 1497 the seal of Ivan III changed - an image of a double-headed eagle appeared on it. Thus, the eagle was not borrowed from Byzantium, but was a logical continuation of the inheritance by the Grand Duke of Moscow of the title of governor of Byzantium.

Around the same time, to commemorate the overthrow of the Tatar-Mongol yoke in 1480, the first monumental image of a double-headed eagle was erected on the spire of the Spasskaya Tower of the Moscow Kremlin. On the remaining towers (Nikolskaya, Troitskaya and Borovitskaya) the coat of arms was installed later.

The best forces were involved in improving the coat of arms. For example, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich invited from Austria such a major master of decorative and applied arts as the Slav Lavrenty Kurelich (Khurelic), called “Herald of the Holy Roman State”, who constructed the Russian state emblem: a black eagle with raised wings on a yellow field with a white horseman in the middle shield. Cartouches with symbolic designations of the regions were scattered along the wings. The state emblem of Russia, and subsequently the Russian Empire, was finally formed in the 17th century. Over the following years, until 1917, it remained virtually unchanged, only a few of its details changed.

In the Russian Empire at the beginning of the 20th century. There were three state emblems: large, medium and small.

The basis of all coats of arms were images of the state black double-headed eagle, crowned with three crowns, holding in its paws the signs of state power - a scepter and an orb. On the eagle's chest is the coat of arms of Moscow with the image of St. George the Victorious slaying a dragon with a spear. The shield of the coat of arms is entwined with the chain of the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called. On the wings of the eagle and around it are the coats of arms of the kingdoms, great principalities and lands that were part of the Russian state.

The large coat of arms also contains images of Saints Michael and Gabriel, an imperial canopy dotted with eagles and lined with ermine, with the inscription "God is with us". Above it is the state banner with an eight-pointed cross on the pole.

The middle coat of arms lacked the state banner and some local coats of arms. In addition, the small coat of arms lacked images of saints, as well as the imperial canopy and the family coat of arms of the emperor. Sometimes a small coat of arms or simply a coat of arms was called a state eagle, having on its wings the coats of arms of the kingdoms and the Grand Duchy of Finland. The purpose of each coat of arms was regulated by a special provision. Thus, the large State Emblem was depicted on the large State Seal, which was attached to state laws and regulations governing charters, to statutes of orders, to manifestos, to diplomas and certificates of princely and count dignity, to patents for the title of consul, etc.

The average State emblem was depicted on the average State seal, which was attached to documents on the rights and privileges of cities, to diplomas for baronial and noble dignity, to instruments of ratification, etc.

The small coat of arms on the small seal was attached to patents for rank, to charters of land grants, to charters to monasteries. The small coat of arms was also depicted on banknotes issued by the state.

The ship's standard featured a large coat of arms. This is how it remained until the October Revolution.

After the February Revolution of 1917, the Provisional Government did not develop a new coat of arms. It only slightly changed the old coat of arms. The double-headed eagle lost all its crowns, signs of imperial power, the coats of arms of the great principalities were removed from its wings and chest, the ends of the wings were lowered down, and under the eagle the building of the Tauride Palace, where the State Duma met, was depicted.

Further events unfolded in such a way that our Fatherland was deprived of its historical relic. The Russian coat of arms, which has a long history, was replaced by the coat of arms of the RSFSR, which was based on the image of the globe and the emblem of labor - a crossed hammer and sickle. With some changes, this coat of arms still exists. An opinion is expressed about the need to approve a new coat of arms, the basis of which is again the double-headed eagle.

This is the history of the standard and the State Emblem; as they say, everything returns to normal. But what about the Naval flag?

The history of the Russian Naval Flag is little known. Back in 1863, the chronicler of the Russian Navy S.I. spoke about this in his short article “Our Flags”. Elagin: “The few information published so far about our flags, without yet presenting an exact idea of either their original form and meaning, or the time of their introduction, however, managed to provide several incorrect data.” It is not surprising that until now, researchers of the history of the Russian flag have not come to a consensus on many issues. For example, even today there are different opinions about what the flags raised on the “Eagle” were like. However, based on some sources, it can be considered that its colors, as already mentioned, were white, blue and red. This is confirmed by documents related to the construction of the ship, among which the following is preserved: “Painting, what else is needed for a ship’s structure, besides what is now purchased overseas.” This “List” indicates exactly how much kindyak is required for flags and a pennant. As for the colors of these flags, they most likely reflected the colors that had long been on the Moscow coat of arms. On a red field there was depicted Saint George in a blue robe on a white horse. In this regard, white, blue and red colors became the state combination already under Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich.

The author of the famous “Essays on Russian Maritime History” F.F. Veselago believes that until 1700 our Naval flag consisted of three stripes - white, blue and red. “From the colors of the materials used for the flags of the ship “Eagle”, and from the fact that the main managers of its armament were the Dutch, it is more likely to assume that the flag of that time, in imitation of the Dutch one, consisted of three horizontal stripes: white, blue and red, arranged, to distinguish them from the Dutch flag, in a different order. The pennant, obviously, was the same three-stripe, white-blue-red.” There is confirmation of this - documents indicating that the tsar ordered three-stripe white-blue-red flags to be sewn for his son Peter.

Veselago further expresses the opinion that this flag was exclusively a naval flag and only since 1705 it became a special flag of Russian merchant ships. But another famous naval historian, P.I., does not agree with his arguments. Belavenets. In his work “Colors of the Russian State National Flag” he refers to the famous engraving “The Capture of the Azov Fortress. 1696”, where the artist A. Schonebeck depicted the flags in the form of a cross dividing their field into four parts.

Thus, if most historians agree on the set of colors of the first Russian Naval flag (white, blue, red), then there is no consensus on its design yet. It still seems to us that F.F.’s version. Veselago is closest to the truth.

Under such a tricolor flag of three stripes in 1688, Peter sailed on his boat - the “grandfather of the Russian fleet”; a similar flag flew on the fun ships of Lake Pleshcheevo in 1692 and on the ships of the Azov fleet in 1696. This flag, Apparently, it became the prototype of the flag with a double-headed eagle in the middle, named in 1693. “Flag of the Tsar of Moscow.”

It is known that for the first time it was raised as a standard on August 6, 1693 by Peter 1 himself on the 12-gun yacht “St. Peter” during his voyage in the White Sea with a detachment of military ships built in Arkhangelsk. This is mentioned by P.I. Belavenets in his work “Do we need a fleet and its significance in the history of Russia.” In 1699-1700 The design of the Peter the Great standard was changed: moving away from the traditional Russian colors, Peter I decided to choose a yellow rectangular panel with a black double-headed eagle in the middle. The development of state shipbuilding in Russia and the creation of a large regular navy created the need for a single flag for all warships. In 1699, Peter I, having tried a number of flag options for warships that operated for a short time, introduced a new, so-called St. Andrew's Naval flag of a transitional design: the rays of a blue diagonal cross rested on the corners of a rectangular three-stripe panel of white-blue-red color.

The St. Andrew's Cross, apparently, was transferred to the Naval flag as one of the most characteristic elements of the first order of Russia, established by Peter I at the very end of the 17th century - the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called. According to Christian tradition, St. Andrew was crucified on a diagonal cross. Peter I explained the choice of the St. Andrew's cross as an emblem for the flag and pennant by the fact that “from this apostle Russia received holy baptism.”

In 1700, Peter separated the sailing fleet from the rowing (galley) fleet and divided it into three general squadrons - corps de battalion (main forces), vanguard and rearguard. At the same time, stern flags were introduced for the ships of these three squadrons: respectively white, blue and red with a blue St. Andrew's cross on a white field in the upper left corner of the flag (at the luff).

With the introduction of the rank of admiral in 1706, the squadron's stern flag, raised on the main topmast (on the topmast of the mainmast), meant that an admiral was on board. If it was raised on the fore topmast (on the topmast of the foremast), then the vice admiral was present on the ship, and if on the cruise topmast (on the topmast of the mizzen mast), then the rear admiral (schoutbenacht). Such flags were called the topmast flags of the first, second and third admirals. In 1710, a new design for the stern flag was established. In the center of the new flag, on a white field, the St. Andrew’s Cross was still located, but its ends did not reach the edges of the cloth, and it seemed as if it was hanging in the air, without touching the flag itself. The first battleship of the Baltic Fleet, Poltava, began its voyage under this flag. In 1712, the blue cross on the white field of the St. Andrew's flag was brought to the edges of the cloth. This design of the St. Andrew's flag existed without changes until the October Revolution.

After the October Revolution, all symbols of the former Russian Imperial Navy were abolished.

On November 18, 1917, the sailors, having gathered at the first All-Russian Congress of the Navy, adopted a resolution: “To raise on all ships of the All-Russian Navy, instead of the St. Andrew’s flag, the flag of the International as a sign that the entire Russian Navy, as one person, stood up for the defense of democracy in the person of the Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies.” It was a red banner without emblems or inscriptions.

On April 14, 1918, by decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, the State Flag of the RSFSR was established - a red rectangular panel with the inscription: “Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.” And from April 20, by order No. 320 of the Navy and the Maritime Department, a red flag with the abbreviation RSFSR written in large white letters in the middle of the flag was introduced on Soviet ships. The second post-revolutionary Naval flag was approved by the People's Commissars for Maritime Affairs and Foreign Affairs of the RSFSR on May 24, 1918 and legalized by the Constitution of the RSFSR, adopted on July 10, 1918. The red (scarlet) banner with the ratio of width and length had a left upper left edged with a gold border in the corner there is the inscription “RSFSR”, made in stylized Slavic script in golden color.

On September 29, 1920, the Soviet government approved a new design for the Naval Flag. This time it had two braids, and in the middle of the red cloth there was a large blue Admiralty anchor, on the spindle of which there was a red five-pointed star on a white lining. Inside the star, a blue hammer and sickle crossed, and on the anchor rod there was the inscription “RSFSR”.

On August 24, 1923, another Naval flag was introduced. On it, in the middle of the red field, there was a white circle with eight white rays diverging in all directions from the center to the edges of the panel. In the white circle there was a red five-pointed star with a white hammer and sickle intersecting. And on November 23, 1926, a special flag was established, which was awarded to ships or formations for special distinctions. It was called Honorary revolutionary naval flag and differed from the usual one by the presence of the Order of the Red Banner on a white field in the upper left corner. The honorary revolutionary Naval flag was made of silk and presented to the ship in a solemn ceremony along with the Order of the Red Banner and a special diploma from the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR. The cruiser Aurora was the first to receive such an award in connection with the tenth anniversary of the revolution, by a resolution of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR dated November 2, 1927.”

Ships and formations awarded this flag began to be called Red Banner. In February 1928, the Baltic Fleet was awarded the Honorary Revolutionary Naval Flag.

On May 27, 1935, by resolution of the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR, the designs and colors of new flags of naval ships and officials were approved. Almost all of them survived until January 1992. The same decree changed the design of the Honorary Revolutionary Naval Flag of the USSR, which became known as the Red Banner Naval Flag of the USSR.

The new type of naval flag was a white rectangular panel, in the left half of which a red five-pointed star is depicted, and in the right half there is a crossed red hammer and sickle. There is a blue border along the lower edge of the panel. The Red Banner Naval Flag differed from the usual one in that the star depicted on it was covered by the image of the Order of the Red Banner.

On June 19, 1942, by order of the People's Commissar of the USSR Navy, the Guards Naval Flag of the USSR was established - it was awarded to the ship at the same time as it was awarded the rank of Guards for special distinctions. Above the blue border, the guards flag additionally depicts a guards ribbon consisting of three black and two orange stripes.

On January 17, 1992, the Russian government deemed it expedient to change the naval symbols. On July 26 of the same year, on Navy Day, the naval flag, covered in the glory of the fiery years of the Great Patriotic War, was raised for the last time on warships of the former USSR Navy. To the sounds of the anthem of the Soviet Union, the flags were then lowered and handed over to the ship commanders for eternal storage. Instead, now accompanied by the anthem of the Russian Federation, the historical St. Andrew's flags and jacks introduced by Peter I were raised.

Every day at a certain time, regardless of the time of sunrise, all warships and auxiliary vessels of the Navy that are moored (at anchor, barrel or moorings) are raised on the stern flagpole, and at sunset the Naval flag is lowered. Along with the flag, during the stay on ships of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd ranks, a jack is lowered and raised.

While at sea, underway, ships carry the flag on a gaff and do not lower it day or night. But what if the ship goes to sea at night, after sunset, when the flag is lowered? Then the flag is raised on the gaff at the moment of transition from the “anchor” position to the “underway” position. When entering the base after sunset, the flag is lowered as soon as the ship is anchored (on the barrel or mooring lines). “During the period of time from raising to lowering the flag, - written in the Ship's Charter - everything When entering (disembarking) a ship (from a ship), military personnel salute the Naval Flag.”

The ship's charter also clearly defines the procedure for raising, lowering and presenting the Naval Ensign on warships and fleet auxiliary vessels.

Every day at eight in the morning local time, and on Sundays and holidays an hour later, the Naval flag is raised on all Navy ships. Both the raising and lowering of the flag are accompanied by a certain ritual regulated by the Ship's Charter. The procedure for this ritual was first outlined in 1720 in Peter’s Naval Charter:

“...In the morning, first of all, one should fire a cannon and rifles, then play a march on all ships, beat the march, raise the flag, and after raising the flag, play and beat the usual dawn... At whatever time the flag is raised and lowered, It is always necessary, both when raising and lowering it, to beat the drums and play a march.” The ritual was carried out similarly. evening “Dawn”, when the flags were lowered.

Over the centuries-old history of the Russian fleet, this ritual has undergone many changes. Here, for example, is how the final part of the flag-raising ceremony in the novel “Major Repairs” is described by the marine painter Leonid Sobolev: “...a silent and quick, permission-seeking turn from the watch commander to the commander, a permissive touch of the commander’s fingers to the visor of his cap - and the silence of the Russian Imperial Navy ended: “Raise the flag and the guy!” At the same time, all at once, the silence burst.

The ringing of bells. Sharp fanfare of bugles, deliberately chosen to be almost out of tune. The sound of oars flying vertically above the boats. The whistle of all the non-commissioned officers' pipes. The fluttering of cap ribbons, torn simultaneously from thousands of heads. The double dry crack of rifles taken on guard: ah, two! The flag slowly rises to the fold, playing with folds... Then the established melody of the bugles and the air in the non-commissioned officer's lungs end. The flag reaches its destination in silence. ...The forges screamed short and high, and the fleet, enchanted by silence and immobility, immediately came to life. The caps flew up on their heads, the guards took “the foot,” turned, raised their rifles and disappeared into the hatches.”

And in our time, the procedure for raising the flag is in many ways similar to Sobolev’s description.

15 minutes before the flag is hoisted, on the orders of the watch officer, the bugler plays a signal “Agenda.” At 7 hours 55 minutes, he sends signalmen to the flag and jack halyards, and then reports to the commander: “The flag will be raised in five minutes.” Bugler plays “Big gathering.” The crew lines up on the upper deck. Only in cases when the ship is in combat readiness or is being prepared for a voyage, the formation of the crew according to the “Big Gathering” is not carried out. However, even then everyone on the upper deck, on command, turns their back to the side of the ship. The ship's commander comes upstairs and greets the personnel. When there is a minute left before the flag is raised, the officer of the watch commands: “On the flag and guy, attention!” Then the command sounds: “Raise the flag and guy!” Buglers play the signal "Raising the Flag" and everyone on the upper deck and nearby piers turns their heads towards the flag, which is slowly raised by the signalmen in an unfurled form. Officers, midshipmen and chief petty officers put their hand to their headgear. The oarsmen of the boats located near the ship (if the situation allows) “dry their oars,” and their foremen also put their hand to their headgear. This is how the daily flag raising takes place.

There is also a ceremonial raising of the flag on ships. In this case, the crew lines up on deck according to the “Big Gathering” in ceremonial or ceremonial dress uniform. At the same time as the flag and jack, topmast flags and color flags are raised, and at this time the orchestra performs the “Counter March”. At the moment when the Navy flag is raised “to its place”, the National Anthem is played. The days and special occasions when the flag is ceremoniously raised on Navy ships are determined by the Ship's Charter. One of these days is the day the ship enters service. The fleet commander or a person appointed by him (usually an admiral), arriving on the ship, solemnly announces the order for the ship to enter service. The ship's commander is then presented with the Naval Ensign and orders. He carries the flag in his hands in front of the formation of the entire crew, and then attaches it to the halyard for hoisting on the stern flagpole or on a gaff and, at the command of the senior commander on board, personally lifts it “to the place.” At the same time, the topmast, topmast flags and color flags are raised. At the same time, the orchestra plays the National Anthem, and the crew greets the raised flag with a loud, drawn-out “Hurray!”

The protection of the ship's ensign in battle became sacred for every sailor. “All military ships are Russian,” said Peter the Great's Naval Charter, - not we must lower the flag to no one.” Our current Navy Naval Charter says this: “The ships of the Navy under no circumstances lower their flag to the enemy, preferring death to surrender to the enemy.”

When anchored, the flag is guarded by a specially appointed sentry, and during battle, when the flags are hoisted on the gaff and topmasts, they are guarded by all crew members who are participating in the battle at their combat posts. If a flag is knocked down during a battle, it will be immediately replaced by another, so that the enemy cannot assume that the flag on the ship is lowered. This maritime custom is also reflected in the Navy's Ship Regulations. “Protection of the State and Naval flags in battle is an honorable duty of the entire crew of the ship,” it is said in this document, - if the State or Naval flag is knocked down in battle, it must be immediately replaced by another. If circumstances do not allow the replacement flag to be hoisted in the designated place, it is hoisted on an emergency flagpole fixed anywhere on the ship.”

The history of the Russian fleet is rich in examples of courage and heroism of Russian sailors. In 1806, in the Adriatic Sea off the coast of Dalmatia, the Russian brig Alexander was attacked by five French ships that tried to capture it. Before the start of the battle, the brig commander, Lieutenant I. Skalovsky, addressed the crew: “Remember: we Russians are here not to count our enemies, but to beat them. We will fight to the last man, but we will not give up. I am sure that the crew of “Alexander” will hold high the honor of the fleet!” The unequal battle lasted several hours. Three times the French tried unsuccessfully to board the Alexander. In a fierce battle, two enemy ships were destroyed by artillery fire, the third lowered its flag and surrendered, the remaining two fled ingloriously.

On May 14, 1829, the 18-gun brig Mercury, cruising off the coast of the Bosphorus, was overtaken by two Turkish battleships with a total of 184 guns on board. The Turks suggested that the Mercury lower the flag, but the crew of the brig unanimously approved the decision of the commander, Lieutenant Commander A.I. Kazarsky to engage in battle, and if there is a threat of capture, to blow up the ship. By skillful maneuvering, Khazarsky constantly positioned his brig in such a way as to make it difficult for the enemy to aim fire. Still, “Mercury” received more than three hundred damages. However, the “Mercury” itself managed to damage the spars and rigging of the enemy battleships with well-aimed fire and force them to drift. For this military feat, "Mercury" was awarded the St. George's stern flag.

The heroic feat of the cruiser “Varyag” and the gunboat “Koreets” will forever go down in the history of our fleet. The beginning of the war with Japan found these Russian ships in the roadstead of the Korean port of Chemulpo. They tried to break through to Port Arthur, but upon leaving the bay they were met by a Japanese squadron of six cruisers, eight destroyers and several other ships. The Russian ships refused the offer to surrender and accepted the battle. Three enemy cruisers received serious damage from well-aimed artillery fire, and one destroyer was sunk. But the Varyag also received several underwater holes through which water entered. The ship tilted to the left side, the strong roll did not allow firing with serviceable guns. The cruiser’s crew suffered heavy losses, the ship’s commander, Captain 1st Rank V.F., was wounded. Rudnev. It was not possible to break the blockade of the Japanese ships, and our ships were forced to return to the Chemulpo roadstead. Here, on the orders of the commander of the Varyag, the Koreets were blown up on the cruiser, and it sank without lowering the flag.

In St. Petersburg, on the Petrograd side, a bronze monument was erected - two sailors open the seams, flooding their ship. This happened on February 26, 1904, when the destroyer Steregushchy was attacked by superior Japanese forces. Destroyer commander Lieutenant A.S. Sergeev, having entered into an unequal battle, damaged two of the four enemy destroyers attacking him. But the Guardian itself lost its power, almost its entire crew and commander died.

The Japanese invited those remaining to surrender - the enemy responded with new shots. To prevent the flag from being knocked down, it was nailed to the gaff. “Steregushchy” fired until the last shell, and when the Japanese sent a boat to bring a towing line to the Russian destroyer, only a few wounded sailors remained alive on it. The engine quartermaster I. Bukharev and the sailor V. Novikov opened the seacocks and went into the abyss along with their mother ship.

During the Great Patriotic War, Soviet sailors also religiously fulfilled the requirement of the Ship's Charter - under no circumstances should they lower the flag in front of the enemy, preferring death to surrender to the enemy.

On August 10, 1941, in an unequal battle with fascist destroyers, the flagpole on the patrol ship “Tuman” was shot down. The wounded sailor Konstantin Semenov rushed to the flag and raised it high above his head, but was wounded a second time by a fragment of an enemy shell and fell to the deck. Radio operator Konstantin Blinov came to Semyonov’s aid. Under enemy fire, they raised the Naval flag. Without lowering the flag, “Fog” disappeared under the water.

A similar feat was accomplished in battle by sailor Ivan Zagurenko on the destroyer Soobrazitelny. This happened in May 1942 when the ship was returning to Novorossiysk from besieged Sevastopol. The destroyer was attacked by fascist torpedo bombers and bombers. The flag halyard was broken by fragments of a bomb that exploded near the side, and the panel of the ship's banner slowly slid down. Zagurenko climbed up the mast to the gaff, picked up the Naval flag and raised it above his head. The sailor held him until the end of the battle, and not a single bullet, not a single fragment touched the brave man.

On August 25, 1942, armed with only a few small cannons, the icebreaking steamer Alexander Sibiryakov was overtaken in the Kara Sea by the fascist heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer. Without doubting an easy victory, the Nazis raised the signal: “Lower the flag, surrender!” The response came immediately: the State flag hoisted on the foremast, and two 76-mm and two 45-mm guns of the steamer immediately struck. This was so unexpected for the Nazis that at first they were confused. The German raider was silent for several minutes, and then the guns of his main caliber began to roar at once. The commander of the Sibiryakov, senior lieutenant Anatoly Kacharava, skillfully maneuvered, returned fire, dodging direct hits. But the forces were too unequal. Shell after shell exploded in the superstructures with a deafening roar, they pierced right through the side and exploded on the deck. Until the last minutes, the Sibiryakov returned fire. In an unequal battle, the ship died, but did not lower its flag to the enemy.

Many such examples, when sailors died along with the ship's banner raised on the masts, were given to us by past wars.

In addition to the Naval Flag, which we talked about, there are two more flags that play an important role in the life of the ship and its crew.

If, due to its technical condition and the level of preparedness of the crew, the ship is capable of successfully solving its inherent combat missions, a pennant is raised on the main topmast (with one mast on the fore topmast). This means that the ship is on a campaign and until its completion it will not lower its pennant, day or night.

The appearance of long and narrow flags - ship pennants - rather like a colored ribbon winding among the spars and rigging, goes back to the distant past of the fleet. Once upon a time, such narrow strips of fabric, attached to the tops of masts, and even on the shrouds, served as a simple device for determining the direction and strength of the wind.

Pennants received a completely different purpose, not at all related to the practical needs of navigation, already in the days of the sailing fleet. The purpose of the pennant was that it served to distinguish a warship from a merchant ship, especially in those countries where the naval and merchant flags were the same. Pennants were raised on the main topmasts of all warships, except the flagship ones. It was a narrow panel up to ten meters long, 10-15 centimeters wide.

The pennants of the first Russian warships were tricolor, white-blue-red, with two braids. In 1700, Peter I established a new pennant design: on the luff adjacent to the halyard, a blue St. Andrew’s cross was placed on a white field, followed by two white-blue-red braids. Subsequently, in accordance with the colors of the flags by division, white pennants were installed for the first division, blue for the second and red for the third division. Since 1865, Russian ships began to carry a single white pennant, except for ships awarded the St. George flag, which carried the corresponding pennant.

The warships of the USSR Navy wore a pennant, which was a narrow red banner with pigtails, with an image of the Navy in the “head”. In addition to the usual narrow (“ordinary”) ship pennants, the fleet also accepts wide ones (the so-called braid pennants), assigned to commanders of detachments of warships of rank below rear admiral. The design of the braid pennant is no different from a regular pennant. The color of the braids of the braid pennant depends on the position of the commander to whom it is assigned, namely: the commander of a ship brigade - red, the commander of a division - blue.

Merchant ships also have pennants - these are triangular flags of various colors, sometimes with a design, letters or numbers indicating that the ship belongs to a particular shipping company, sports club, trading company, etc. Similar pennants are raised on the mainmast at the entrance to and exit from the port. When staying in a port, the raising and lowering of such a pennant is carried out simultaneously with the raising and lowering of the State Flag.

On military ships, the pennant is lowered only when the ship is visited by the commander of the unit or other superior officers, who are assigned their own official flags. The pennant is lowered at the moment when the raised official flag reaches “the place”. It rises again with the departure of this person from the ship and with the lowering of his official flag.

The presence of a pennant on a ship indicates its completeness and combat readiness. There is even such an expression in the navy: a squadron (or fleet) consisting of so many pennants. The word “pennant” in this case means a warship at sea ready for combat.

We have already mentioned that on modern large warships, when they are anchored, on a barrel or at a pier, a special flag-huy is raised on the bow flagpole.

In ancient times, on the bowsprit of warships, the same flags were permanently or temporarily raised as on the stern, only slightly smaller in size. On the ships of the Russian fleet, a special bow (or bowsprit) flag, called a guy, was introduced in 1700. The design of the first Russian guy was quite complex - on a red field there were three crosses with a single center: straight - white, oblique - also white and on it blue Andreevsky. From 1701 to 1720 it was raised only in coastal fortresses, and only after the introduction of the Charter of 1720 it began to be raised on the bowsprit of warships. Until 1820, ships carried it not only when stationary, but also while sailing. The huys was always smaller in size than the stern flag.

Initially, the gyus on Russian ships was called geus, which means flag in Dutch , and since 1720, Peter’s Naval Charter legalized the name “guys”. The word is also Dutch (geuzen) and comes from French gueux- beggars. At the beginning of the Dutch bourgeois revolution, the Spanish aristocracy called the Dutch nobles who, from 1565, stood in opposition to the Spanish king Philip II and his government, and then the popular guerrilla rebels who waged an armed struggle against the Spaniards on land and sea. The Gueuze revolt marked the beginning of the creation of the Dutch navy. Then they began to raise a special flag on the bowsprit of warships, repeating the colors of the coat of arms of the Prince of Orange, who led the Gueuze uprising. The name “guez” or “geus” soon became attached to this flag.

The guy, introduced by Peter I, remained in the Soviet Navy until August 28, 1924. The design of the new guy differed from the old one by the presence in the middle of the panel of a white circle with the image of a red five-pointed star with a white intersecting hammer and sickle in its center. On July 7, 1932, a new guy was approved. It was a rectangular red panel, in the middle of which, surrounded by a white border, there is a red five-pointed star with a hammer and sickle in its center.

The huys is raised daily in the bow of warships of the 1st and 2nd rank on a special huyspole simultaneously with the raising of the stern flag. It is also raised on the masts of coastal batteries or at salute points of coastal fortresses when returning a salute to foreign warships. The guis, raised on the masts of seaside fortresses, is a serf flag. Time will tell whether a ship's standard will be introduced.

I was inspired by one of the previous posts and dived into the history of the flag vault.

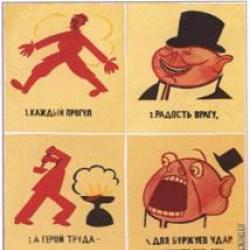

So, the naval flag signaling system was introduced by the French in the second half of the 18th century, and then picked up by sailors of all fleets. At first, only digital flags were used, but half a century later the International Code of Signals was founded, consisting of 26 letter flags, 10 digital pennants and several special flags with which one could send a signal and even compose a complex message. This is what Nelston's famous signal looked like before the Battle of Trafalgar on October 21, 1805. This is a reconstruction of the signal on Nelson's ship Victory in honor of the 200th anniversary of the battle. As we can see, they couldn’t even post the entire phrase. Lost skills, alas...

In general, in order to be understood, you had to be quick and smart in transmitting the signal. The number of identical flags on board was limited, so replacement flags were introduced, which, depending on the location, could replace any of the ones already in use. The 1st substitute is read as the top one in the group, the second as one lower, etc.

The technique of assembling flags into a group has also improved. Tying knots made the signalman's work difficult, especially with wet and icy halyards. In 1888, Edward Inglefield, flag lieutenant of the commander of the English squadron, invented a special bracket that greatly simplified the set. His ship instantly became the winner of all signaling competitions, and since 1900 this simple device has been used in the navy.

On the ship, the flags were stored in a special signal box with cells folded in a special way. The dialed three-flag signal was raised on the mast to a place in the folded state, and then with one jerk all the flags unfurled.

In addition to the International Code of Signals, each navy had its own code and one flag could have different meanings in them. Signalers of warships had to learn two classes. The fleets of NATO countries have unified their codes, the code of the Russian Navy is still special, as is the alphabet.

How did they control the maneuvers of ships using flags? Let’s say the ships are sailing in wake formation and the flagship gives the command: “Suddenly turn everyone to the right by 90°.” To do this, he raises a signal on the mast (hereinafter all signals are from the British Navy code).

The ships of the formation raise the response pennant to half when they see the signal and to the place when the signal is disassembled. If distant matelots cannot make out the flagship's signal, intermediate ships rehearse it.

When all ships have cleared the signal, the flagship quickly lowers the flags, which is the moment the maneuver begins.

There were often annoying mistakes when the signalman missed the halyard and the entire set of flags fluttered unreadably in the wind. Then the signal was quickly reassembled on the halyard of the other side, and the missed flags were caught with a special device.

From this it is clear how important an element of combat training was the training of signalmen. Therefore, their actions were practiced until they were automatic on land before being allowed to reach the signal bridge.

Nevertheless, tragic accidents occurred, not only due to the fault of signalmen, but also of admirals. In 1893, the British Mediterranean Fleet operated under the command of Vice Admiral George Tryon.

The admiral was a great inventor, skilled in maneuvering and loved to test his commanders, as well as test new ideas on his ships. Like most admirals of that time, he wore a beard, was formidable, decisive and had unquestioned authority among his subordinates. His deputy was Rear Admiral Markham, who commanded the second division.

At the beginning of the maneuver, the fleet was moving in two divisional wake columns. The commander's idea was this: the 1st division would turn sequentially after its flagship to the left, and the 2nd to the right. After the flagships are level, both columns turn “all of a sudden” to the left and anchor in the Tripoli roadstead. The problem was that the distance between the wake columns was only 6 cables, and the circulation diameter of the ships was about 4 cables. In order to safely perform such a maneuver, the distance had to be at least 10 cabs. The admiral's subordinates timidly tried to draw his attention to this fact, but he snapped something like "I said it!" After that, everyone concluded that the giraffe was big, he knew better, and flag signals went up the mast.

Other ships raised their reciprocal pennants to half-mast. They all realized that the maneuver was impossible, but like the admiral's staff, they finally concluded that the senior commander knew what he was doing, and raised the pennant to the spot. Except for the junior flagship, where Rear Admiral Markham was still wondering what to do. Then Admiral Tryon used the standard method to bring the unwary subordinate to his senses. He sent a semaphore: “What are you waiting for?” After this, Markham calmed down enough to confirm the clarity of the signal, and at an executive command the ships began to turn towards their fate.

At the end of its circulation, the Camperdown rammed the Victoria, which sank 20 minutes later, taking with it 400 sailors, led by the culprit, Admiral Tyrone. They say that his last words were “It’s all my fault.” However, if at least one ship had not raised the return pennant to the spot, the disaster would not have happened.

One of the famous flag signals was the one that began the main stage of the famous Battle of Jutland. The Grand Fleet, consisting of 24 battleships, sailed in six wake columns under the command of Admiral John Jellicoe. The same one who, as a lieutenant, escaped from the drowning of the Victoria. At 18.14 on May 31, 1916, he received a report from the commander of the battlecruiser squadron, Beatty: “Spotted enemy battle fleet on SSW bearing.” Directly ahead of the squadron there was a strip of fog, and behind it was the target - Hochseefleet, heading to the northeast. Jellicoe immediately decided to reform into one wake column and “envelop the head” of the German formation. Within a minute, a signal of only 3 flags soared onto the mast of the flagship battleship Iron Duke, which accurately described the assigned formation change. A magnificent maneuver, which entered the annals of naval history, gave the Grand Fleet the opportunity to encircle the head of the enemy fleet and cut it off with its main forces from the base.

Signal flags were widely used for all kinds of jokes. Often they conveyed numbers of psalms or chapters from the Bible that were relevant to the episode.

On the right is a brooch that the naughty King Edward VII gave to his mistress Alice Cappel after their sailing together on a yacht, where they diligently studied flag signals. It conveys a message in maritime language:

“I can clearly see the target, I’m ready to fire a Whitehead torpedo (or a white-headed torpedo, on another reading) straight ahead.” History is silent about how often the girl wore the royal gift, especially in the presence of naval officers.

And finally, there is a long tradition of hanging the so-called. "gin pennant" in front of open bars. Moreover, if in Russian people go there “to the left,” then the British chose to designate the hot spot a flag indicating “turn to the right.” What can we do, there really is a cultural gap between us!

Sailors, like everyone else, have “ language", but he is unusual. It is classified as a signaling device.

Visual signaling means are divided into:

- for subject signaling means: signal flags, figures, flag semaphore; - by means of light communications And alarm: signal lights, spotlights, spot and signal lights;

- for pyrotechnic signaling devices: signaling and lighting and signal cartridges, rockets, torches.

Sound signaling means are: sirens, megaphones, typhons, beeps, etc. I bring to your attention - flag semaphore. With its help, messages are sent and received between people within line of sight. Used in case of failure of radio equipment. Knowledge of this language will help not only at sea. Knowledge of English is required.

International Code of Signals- signal books containing a list of individual words and sentences most often found in maritime practice, with corresponding symbols in the form of short combinations of numbers and letters. Conventions intended for negotiations ships, ships and coastal communication and observation posts with foreign ships and coastal posts using visual and technical communications.

The semaphore or flag alphabet has been used in the Navy since 1895. It was developed by Vice Admiral Stepan Makarov. The Russian flag alphabet contains 29 letters and three special characters and does not include numbers or punctuation marks. The transmission of information in this type of communication is carried out in words, letters by letter, and the transmission speed can reach 60-80 characters per minute. The signalman is responsible for transmitting information using the semaphore alphabet on the ship; this specialty in the navy was introduced in 1869.

international maritime signal flags and pennants

International Code of Signals flags were developed in 1857. They are used on navy to transmit messages between everyone ships. Before 1887 vault was called " Code signal system for the merchant fleet" Initially the vault consisted of 18 flags. On January 1, 1901, all maritime states accepted this vault. In 1931, an international commission from 8 countries modified signal system.

flags of the naval code of signals