Alexander I: biography. Emperor Alexander I and his personal life Alexander 1 whose son and grandson

Valdai prison. 1838. The investigator interrogates a woman who has just been brought in, whom the police considered suspicious. She is wearing tattered clothes, but the woman does not look like a beggar at all. No documents were found on her. A passer-by said that her name was Vera.

- Who are you? the investigator asks, stuffing his pipe with tobacco. The secretary dunks his pen into the inkwell, preparing to take notes.

The woman, who until then stood with her head bowed, raises a meek look at her jailers.

- Judging by the heavenly, then I am the dust of the earth, and if by the earthly, then I am above you!

The woman did not answer any more questions. For the next twenty-three years she lived with a meal of silence.

Her last words, recorded in the prison book, remained unsolved.

Was the Siberian beggar Vera Alexandrova Grand Duchess Elizabeth Alekseevna, the wife of Alexander the First?

Elizaveta Alekseevna - wife of Alexander I

Louise-Maria-Augusta of Baden was brought to St. Petersburg in 1792, at the age of thirteen. Catherine the Second saw in this girl the best candidate for a wife for her grandson, heir to the throne - Alexander. Alexander himself had not yet reached the age of majority, but the kind grandmother had already sent maids of honor experienced in love pleasures to his apartments. It seemed to Catherine that this experience would help the young man in his early family life, but everything turned out the other way around.

The wedding of Alexander and Elizabeth, as the Baden princess was called in Russia, turned out to be luxurious and promising. Lizaveta Alekseevna and Alexander Pavlovich were a brilliant couple - beautiful, like heroes of myths. When they were brought to the altar, Catherine II exclaimed:

- It's Cupid and Psyche!

Gavrila Derzhavin, who was present at the wedding, immediately issued an impromptu:

Cupid thought Psyche

frolic, fuck,

Entangle flowers with her

And tie a knot.

Beautiful captive blushes

And breaks away from him

And he seems to be shy

From this case.

Family life turned out to be completely different from an idealistic poem - the inexperienced, timid Elizaveta Alekseevna could not give Alexander what he expected from his wife. Elizabeth withdraws into herself, tries to appear less often in public, most often spends time with books and diaries.

Catherine II dreamed of placing her grandson, Alexander, on the throne, bypassing her son, Pavel. But she died without having figured out how to implement her idea. Paul ascended the throne. Alexander gathered a circle of young people like himself, and at night, in a whisper, they talked about the overthrow of Paul.

But the fate of the emperor was decided by other people. Count Palen simply locked Alexander and his brother in a room, and released him only when their father was dead.

This event further aggravated the condition of Elizabeth Petrovna, she fell into deep melancholy. Yes, and Alexander, who was now to become king, also showed no signs of courage. Count Pahlen whispered in his ear the words he should have said announcing his father's death.

Alexander said in a trembling voice:

- Pavel is dead ... Now everything will be like under Catherine ...

And this phrase was not only about public policy. The royal court took these words as a start to general debauchery.

Alexander himself openly got himself a mistress, the brawler Naryshkina - the direct opposite of Elizaveta Alekseevna.

- Oh, I don't feel well! - Naryshkina once said to Elizabeth during the ball. And added emphatically:

- I am pregnant!

Elizabeth knew perfectly well who the father was ...

But she dutifully accepted the blow.

In order to somehow distract herself, Elizabeth began to read French philosophers and was carried away by the ideas of freedom, equality and fraternity. She took up helping the poor and spent her entire budget on charity.

“I came to this country with nothing,” she said, “and I will die with nothing ...

Elizabeth frankly advocated the equality of people - she hated when her hand was kissed and insisted on a handshake. And if a woman kissed her hand, then Elizabeth leaned over and defiantly kissed the kissing hand.

Secret societies, banned by Alexander, but actively continuing to exist, advocated radical measures and a complete reorganization of the state. Alexander the First was a supporter of gradual reforms, for example, he advocated the gradual abolition of serfdom. In his opinion, the process should have taken at least sixty years!

Alexander did not suit either the Freemasons or those who would one day be called Decembrists. At their gatherings, a new topic began to be exaggerated - it was proposed to remove Alexander the First from the throne and put Elizabeth in his place!

- For Elizabeth II! - clinking glasses of champagne Russian officers who returned from France, who defeated Napoleon ...

Elizabeth seemed to them a wise, democratic ruler - moreover, childless. The absence of an heir would be another step towards the complete abolition of autocracy.

But the oppositionists clearly did not think that Elizaveta Alekseevna would never go against Alexander. Even her first lover, Adam Czartoryski, she let in on her own husband's whim! When this connection was found out in the palace, Adam was sent abroad. But the child born to Elizabeth, Alexander the First recognized as his own.

This was a girl. She lived only a year and became very ill. The poorly educated court doctors treated her with camphor and musk, which only made her worse.

Having lost a child, Elizabeth once again felt the meaninglessness of her existence in the royal palace, where she was brought as a child.

But she tried to make others happy. When she was presented with a book by the unknown poetess Anna Bunina as a gift, she ordered that she be given a monetary allowance, realizing that otherwise the poetess would have nothing to live on. Anna Bunina, thanks to the help of Elizabeth, made a career.

Once, while reading Bunina's poems, mostly devoted to love, Elizabeth sat down by a huge mirror. She felt like an old woman, but in the reflection a very beautiful woman looked at her, who was not spoiled by sadness ...

- God! Take my beauty! - Elizaveta pleaded, - From my beauty there is only a temptation!

After all, today she was again pursued by obsessive gentlemen, and one - a young cavalry guard - is now standing under the window.

Elizabeth opened the window towards the summer night and suddenly, without expecting it herself, beckoned to the young handsome man standing below.

Not believing his luck, he deftly climbed a tree growing nearby and jumped into Elizabeth's window ... His name was Alexei Okhotnikov.

Elizabeth wanted to give the memories of this passionate connection to her best friend, the historian Karamzin. But the diaries fell into the wrong hands and were burned ...

The denouement of this story was no less tragic than the whole life of Elizabeth. A stranger shot at Okhotnikov, moreover, with a poisoned bullet. Alexei was ill for four months. On the night of his death, Elizabeth had a daughter, Eliza. And Alexander the First again recognized the child, and fell in love with the girl even more than his own children born to Naryshkina.

In general, Alexander is credited with eleven illegitimate children. On the other hand, the fact that, being a man filled with a sense of duty, the emperor did not have children from his official wife is a big mystery. It is likely that the eleven children were a cover for the sovereign's infertility and were born by his mistresses from other men.

Little Eliza was allotted by God only two years of life. And again, the doctors sprayed camphor and musk so that Elizabeth could no longer endure these smells all her life.

Heartbroken, Elizabeth fell ill. With the last of her strength, she appeared at charity receptions and worked on organizing a women's patriotic society.

Naryshkina, aging, began to make scandals to the emperor and demand that he marry her. Alexander suddenly looked at the situation with different eyes. He realized that all these years he had a wonderful wife, Elizabeth, ready for him to go through fire and water ...

He leaves Naryshkina and decides to take care of his wife's failing health, offering her a trip to Italy.

“I want to die in Russia,” Elizabeth firmly declares.

- No, you won't die! You are still young! - the emperor exclaimed with unusual fervor, - We will go to Taganrog - there is a wonderful climate!

The trip to Taganrog, where the palace was prepared for the arrival of the imperial couple, became a turning point in the history of Russia.

In Taganrog, Elizabeth and Alexander lived for two months, and it was the happiest time in their lives. They suddenly realized how much they love each other ... From such a favorable atmosphere, Elizabeth's health began to improve. According to the memoirs of contemporaries, she looked good and could even defend the vigil.

State affairs forced Alexander to leave Taganrog for a short time ... He returned completely sick.

He died in his wife's arms, whispering words of love to her. Less than a month later, an uprising of the Decembrists took place, trying to prevent his brother Nikolai from the Russian throne.

Elizabeth's illness returned with renewed vigor, and she could not go to St. Petersburg for her husband's funeral.

For four months, Elizabeth lived in Taganrog, and suddenly decided to return to St. Petersburg, but she could only get to Belev. There, a dinner was arranged in her honor, and eyewitnesses said that she looked very sick and could hardly walk ... That night she died. Her body was sent to Petersburg in a sealed coffin. None of her immediate family saw her dead.

Elizabeth was buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral. Ordinary people cried, seeing her off on her last journey. The unfortunate fate of this most beautiful woman is overgrown with legends.

In the Tikhvin Monastery, the grave of the old woman-silent Vera, who many consider to be the empress who has gone into monasticism, has now been restored. The flowers from her grave are said to cure diseases.

Son of Pavel Petrovich and Empress Maria Feodorovna; genus. in St. Petersburg on December 12, 1777, ascended the throne on March 12, 1801, † in Taganrog on November 19, 1825. The Great Catherine did not love her son Pavel Petrovich, but she took care of raising her grandson, whom, however, she early deprived of maternal supervision for these purposes. The empress tried to put his upbringing to the height of her contemporary pedagogical requirements. She wrote "grandmother's alphabet" with anecdotes of a didactic nature, and in the instructions given to the teacher of the Grand Dukes Alexander and (his brother) Konstantin, Count (later Prince) N. I. Saltykov, with the highest rescript of March 13, 1784, she expressed her thoughts "regarding health and preserving it; regarding the continuation and reinforcement of the inclination towards goodness, regarding virtue , courtesy and knowledge" and the rules "to supervisors regarding their behavior with pupils". These instructions are built on the principles of abstract liberalism and are imbued with the pedagogical inventions of Emile Rousseau. The implementation of this plan was entrusted to different persons. The conscientious Swiss Laharpe, an admirer of republican ideas and political freedom, was in charge of the intellectual education of the Grand Duke, read with him Demosthenes and Mably, Tacitus and Gibbon, Locke and Rousseau; he managed to earn the respect and friendship of his student. La Harpe was assisted by Kraft, a professor of physics, the famous Pallas, who read botany, and the mathematician Masson. The Russian language was taught by the famous sentimental writer and moralist M. N. Muravyov, and the law of God was taught by Fr. A. A. Samborsky, a more secular person, devoid of a deep religious feeling. Finally, Count N. I. Saltykov cared mainly about maintaining the health of the Grand Dukes and enjoyed the favor of Alexander until his death. In the upbringing given to the Grand Duke, there was no strong religious and national foundation, it did not develop personal initiative in him and protected him from contact with Russian reality. On the other hand, it was too abstract for a young man of 10-14 years old and glided over the surface of his mind without penetrating deep. Therefore, although such an upbringing evoked in the Grand Duke a number of humane feelings and vague ideas of a liberal nature, it did not give either one or the other a definite form and did not give the young Alexander the means to implement them, therefore, it was deprived of practical significance. The results of this upbringing affected the character of Alexander. They largely explain his impressionability, humanity, attractive treatment, but at the same time some inconsistency. The education itself was interrupted in view of the early marriage of the Grand Duke (16 years old) to the 14-year-old Princess Louise of Baden, Grand Duchess Elisaveta Alekseevna. From a young age, Alexander was in a rather difficult position between his father and grandmother. Often, present in the morning at parades and exercises in Gatchina, in a clumsy uniform, in the evening he appeared among the refined and witty society that gathered in the Hermitage. The need to be perfectly reasonable in these two spheres taught the Grand Duke to secrecy, and the discrepancy that he encountered between the theories inspired by him and the bare Russian reality instilled in him distrust of people and disappointment. The changes that took place in court life and public order after the death of the empress could not favorably influence the character of Alexander. Although at that time he served as the St. Petersburg military governor, he was also a member of the Council, the Senate, and the chief of the l.-g. Semyonovsky regiment and presided over the military department, but did not enjoy the confidence of Emperor Pavel Petrovich. Despite the difficult situation in which the Grand Duke was at the court of Emperor Paul, he already at that time showed humanity and meekness in dealing with his subordinates; these properties so seduced everyone that even a person with a stone heart, according to Speransky, could not resist such treatment. Therefore, when Alexander Pavlovich ascended the throne on March 12, 1801, he was greeted by the most joyful public mood. Difficult political and administrative tasks awaited their resolution from the young ruler. Still little experienced in matters of government, he preferred to adhere to the political views of his great grandmother, Empress Catherine, and in a manifesto of March 12, 1801, he announced his intention to govern the people entrusted to him by God according to the laws and "after the heart" of the late empress.

The Treaty of Basel, concluded between Prussia and France, forced Empress Catherine to join with England in a coalition against France. With the accession to the throne of Emperor Paul, the coalition fell apart, but was renewed again in 1799. In the same year, Russia's alliance with Austria and England broke again; rapprochement between the St. Petersburg and Berlin courts was discovered, peaceful relations began with the first consul (1800). Emperor Alexander hurried to restore peace with England by convention on 5 June and concluded peace treaties on 26 September with France and Spain; the decree on the free passage of foreigners and Russians abroad, as it was before 1796, dates back to the same time. Having thus restored peaceful relations with the powers, the emperor devoted the first four years of his reign almost all his strength to internal, transformative activity. The transformative activity of Alexander was primarily aimed at the destruction of those orders of the past reign, which modified the social order, destined by the great Catherine. Two manifestos, signed on April 2, 1801, were restored: a charter to the nobility, a city status and a charter given to cities; soon after, a law was again approved that freed priests and deacons, along with personal nobles, from corporal punishment. The secret expedition (which, by the way, was established under Catherine II) was destroyed by the manifesto of April 2, and on September 15 it was ordered to establish a commission to review previous criminal cases; this commission really eased the fate of persons "whose guilt was unintentional and more related to the opinion and way of thinking of that time than to dishonorable deeds and real harm to the state." Finally, torture was abolished, foreign books and notes were allowed to be imported, and private printing houses were opened, as it was before 1796. The transformations, however, consisted not only in restoring the order that existed before 1796, but also in replenishing it with new orders. The reform of local institutions, which took place under Catherine, did not affect the central institutions; meanwhile they, too, demanded restructuring. Emperor Alexander set about this difficult task. His collaborators in this activity were: insightful and knowing England better than Russia gr. V. P. Kochubey, smart, learned and capable N. N. Novosiltsev, admirer of the English order, Prince. A. Czartoryski, a Pole by sympathy, and c. P. A. Stroganov, who received an exclusively French upbringing. Shortly after accession to the throne, the sovereign established an indispensable council instead of a temporary council, which was subject to consideration of all the most important state affairs and draft regulations. Manifesto of 8 Sept. In 1802, the significance of the Senate was determined, which was instructed to "consider the acts of ministers in all parts of their administration entrusted and, according to the proper comparison and consideration of these with state decrees and reports that have reached the Senate directly from the places, make their conclusions and submit a report" to the sovereign. The significance of the highest judicial authority was left to the Senate; only the First Department retained its administrative significance. By the same manifesto on 8 Sept. central administration is divided among 8 newly established ministries, which are the ministries: military land forces, naval forces, foreign affairs, justice, finance, commerce and public education. Each ministry was under the control of a minister, to whom (in the ministries of the interior and foreign affairs, justice, finance and public education) a comrade was attached. All ministers were members of the Council of State and were present in the Senate. These transformations, however, were carried out rather hastily, so that the old institutions were faced with a new administrative order, not yet fully determined. The Ministry of Internal Affairs earlier than others (in 1803) received a more complete device. - In addition to a more or less systematic reform of the central institutions, in the same period (1801-1805) separate orders were made regarding social relations and measures were taken to spread public education. The right to own land, on the one hand, and engage in trade, on the other, is extended to different classes of the population. Decree 12 Dec. In 1801, the merchants, bourgeoisie and state-owned settlers were given the right to acquire land. On the other hand, in 1802 the landlords were allowed to carry out wholesale trade abroad with the payment of guild duties, and also in 1812 the peasants were allowed to carry out trade in their own name, but only on the basis of an annual certificate taken from the county treasury with payment of the required duties. Emperor Alexander sympathized with the idea of freeing the peasants; To this end, several important measures have been taken. Under the influence of the project on the liberation of the peasants, filed by c. S. P. Rumyantsev, the law on free cultivators was issued (February 20, 1803). According to this law, the peasants could enter into deals with the landowners, be released from the land and, without registering in another state, continued to be called free cultivators. It was also forbidden to make publications about the sale of peasants without land, the distribution of populated estates was stopped, and the regulation on the peasants of the Livland province, approved on February 20, 1804, alleviated their fate. Along with the administrative and estate reforms, the revision of laws continued in the commission, the management of which was entrusted to Count Zavadovsky on June 5, 1801, and a draft code began to be drawn up. This code was supposed, in the opinion of the sovereign, to complete a number of reforms undertaken by him and "protect the rights of everyone and everyone", but remained unfulfilled, except for one general part (Code général). But if the administrative and social order was not yet reduced to the general principles of state law in the monuments of legislation, then in any case it was spiritualized thanks to an ever wider system of public education. On September 8, 1802, a commission (then the main board) of schools was established; she developed a regulation on the organization of educational institutions in Russia. The rules of this regulation on the establishment of schools, divided into parish, district, provincial or gymnasiums and universities, on orders for the educational and economic parts were approved on January 24, 1803. The Academy of Sciences was restored in St. Petersburg, new regulations and staff were issued for it, a pedagogical institute was founded in 1804, and in 1805 - universities in Kazan and Kharkov. In 1805, P. G. Demidov donated a significant amount of capital to the establishment of a higher school in Yaroslavl, gr. Bezborodko did the same for Nezhin, the nobility of the Kharkov province petitioned for the founding of a university in Kharkov and provided funds for this. Technical institutions were founded, which are: a commercial school in Moscow (in 1804), commercial gymnasiums in Odessa and Taganrog (1804); the number of gymnasiums and schools has been increased.

But all this peaceful reform activity was soon to cease. Emperor Alexander, unaccustomed to the stubborn struggle with those practical difficulties that he so often encountered on the way to the implementation of his plans, and surrounded by inexperienced young advisers who were too little familiar with Russian reality, soon lost interest in reforms. In the meantime, the dull rumblings of the war, which was impending, if not on Russia, then on neighboring Austria, began to attract his attention and opened up to him a new field of diplomatic and military activity. Shortly after the Peace of Amiens (March 25, 1802), a break again followed between England and France (beginning of 1803) and hostile relations between France and Austria resumed. Misunderstandings also arose between Russia and France. The patronage provided by the Russian government to Dantreg, who was in the Russian service with Christen, and the arrest of the latter by the French government, the violation of the articles of the secret convention of October 11 (N.S.) 1801 on the preservation of the possessions of the King of the Two Sicilies inviolability, the execution of the Duke of Enghien (March 1804) and the adoption of the imperial title by the first consul - led to a break with Russia (August 1804). Therefore, it was natural for Russia to draw closer to England and Sweden at the beginning of 1805 and to join the same alliance with Austria, friendly relations with which began even with the accession of Emperor Alexander to the throne. The war opened unsuccessfully: the shameful defeat of the Austrian troops at Ulm forced the Russian forces sent to help Austria, with Kutuzov at the head, to retreat from Inn to Moravia. The affairs under Krems, Gollabrun and Shengraben were only ominous harbingers of the Austerlitz defeat (November 20, 1805), in which Emperor Alexander was at the head of the Russian army. The results of this defeat affected: in the retreat of the Russian troops to Radziwillov, in the uncertain, and then hostile attitudes of Prussia towards Russia and Austria, in the conclusion of the Peace of Pressburg (December 26, 1805) and the Schönbrunn defensive and offensive alliance. Before the defeat of Austerlitz, Prussian relations with Russia remained extremely uncertain. Although Emperor Alexander managed to persuade the weak Friedrich Wilhelm to approve the secret declaration on May 12, 1804 regarding the war against France, but already on June 1 it was violated by new conditions concluded by the Prussian king with France. The same fluctuations are noticeable after the victories of Napoleon in Austria. During a personal meeting, imp. Alexander and the king in Potsdam concluded the Potsdam Convention on October 22. 1805 Under this convention, the king undertook to contribute to the restoration of the conditions of the Luneville peace violated by Napoleon, to accept military mediation between the warring powers, and in case of failure of such mediation, he had to join the Coalition. But the Peace of Schönbrunn (December 15, 1805) and even more so the Paris Convention (February 1806), approved by the King of Prussia, showed how little one could hope for consistency in Prussian policy. Nevertheless, the declaration and counter-declaration, signed on July 12, 1806, at Charlottenburg and on Kamenny Island, revealed a rapprochement between Prussia and Russia, a rapprochement that was confirmed by the Bartenstein Convention (April 14, 1807). But already in the second half of 1806 a new war broke out. The campaign began on October 8, was marked by terrible defeats of the Prussian troops at Jena and Auerstedt, and would have ended with the complete subjugation of Prussia if Russian troops had not come to the aid of the Prussians. Under the command of M.F. Kamensky, who was soon replaced by Bennigsen, these troops put up strong resistance to Napoleon at Pultusk, then were forced to retreat after the battles of Morungen, Bergfried, Landsberg. Although the Russians also retreated after the bloody battle of Preussisch-Eylau, Napoleon's losses were so significant that he unsuccessfully sought an opportunity to enter into peace negotiations with Bennigsen and corrected his affairs only with a victory at Friedland (June 14, 1807). Emperor Alexander did not take part in this campaign, perhaps because he was still under the impression of the Austerlitz defeat, and only on April 2. In 1807 he came to Memel to meet with the King of Prussia, who was deprived of almost all his possessions. The failure at Friedland forced him to agree to peace. Peace was desired by a whole party at the court of the sovereign and the army; the ambiguous behavior of Austria and the emperor's displeasure with regard to England were also prompted; finally, Napoleon himself needed the same peace. On June 25, a meeting took place between Emperor Alexander and Napoleon, who managed to charm the sovereign with his mind and insinuating treatment, and on the 27th of the same month, the Treaty of Tilsit was concluded. According to this treatise, Russia acquired the Belostok region; Emperor Alexander ceded Cattaro and the republic of 7 islands to Napoleon, and the Principality of Ievre to Louis of Holland, recognized Napoleon as emperor, Joseph of Naples as king of the Two Sicilies, and also agreed to recognize the titles of Napoleon's other brothers, present and future titles of members of the Confederation of the Rhine. Emperor Alexander took over the mediation between France and England and in turn agreed to Napoleon's mediation between Russia and the Porte. Finally, according to the same peace, "out of respect for Russia," the Prussian king was returned to his possessions. - The Treaty of Tilsit was confirmed by the Erfurt Convention (September 30, 1808), and Napoleon then agreed to the annexation of Moldavia and Wallachia to Russia.

When meeting in Tilsit, Napoleon, wanting to divert the Russian forces, pointed Emperor Alexander to Finland and even earlier (in 1806) armed Turkey against Russia. The reason for the war with Sweden was the dissatisfaction of Gustav IV with the Peace of Tilsit and his unwillingness to enter into armed neutrality, restored in view of the break between Russia and England (October 25, 1807). War was declared on March 16, 1808. Russian troops, commanded by c. Buxhowden, then c. Kamensky, occupied Sveaborg (April 22), won victories at Alovo, Kuortan and especially at Orovais, then crossed over the ice from Abo to the Aland Islands in the winter of 1809 under the command of Prince. Bagration, from Vasa to Umeå and through Torneo to Vestrabonia under the leadership of Barclay de Tolly and gr. Shuvalov. The successes of the Russian troops and the change of government in Sweden contributed to the conclusion of the Friedrichsham Peace (September 5, 1809) with the new king, Charles XIII. According to this world, Russia acquired Finland to the river. Torneo with the Aland Islands. Emperor Alexander himself visited Finland, opened the Diet and "preserved the faith, the fundamental laws, the rights and privileges that hitherto had been enjoyed by every estate in particular and all the inhabitants of Finland in general according to their constitutions." A committee was set up in St. Petersburg and a secretary of state for Finnish affairs was appointed; in Finland itself, executive power was handed over to the Governor-General, legislative power to the Governing Council, which later became known as the Finnish Senate. - Less successful was the war with Turkey. The occupation of Moldavia and Wallachia by Russian troops in 1806 led to this war; but until the Treaty of Tilsit, hostilities were limited to Michelson's attempts to occupy Zhurzhu, Ishmael and some friends. fortress, as well as the successful actions of the Russian fleet under the command of Senyavin against the Turkish, which suffered a severe defeat at Fr. Lemnos. The peace of Tilsit stopped the war for a while; but it resumed after the Erfurt meeting, in view of the refusal of the Porte to cede Moldavia and Wallachia. The failures of the book Prozorovsky were soon corrected by the brilliant victory of Count. Kamensky at Batyn (near Ruschuk) and the defeat of the Turkish army at Slobodze on the left bank of the Danube, under the command of Kutuzov, who was appointed to the place of the deceased c. Kamensky. The successes of Russian weapons forced the sultan to peace, but the peace negotiations dragged on for a very long time, and the sovereign, dissatisfied with the slowness of Kutuzov, had already appointed Admiral Chichagov as commander-in-chief when he learned about the conclusion of the Bucharest peace (May 16, 1812). ). According to this peace, Russia acquired Bessarabia with the fortresses of Khotyn, Bendery, Akkerman, Kiliya, Izmail to the Prut River, and Serbia - internal autonomy. - Next to the wars in Finland and on the Danube, Russian weapons had to fight in the Caucasus. After the unsuccessful administration of Georgia, Gen. Knorring was appointed chief governor of Georgia, Prince. Tsitsianov. He conquered the Jaro-Belokan region and Ganzha, which he renamed Elisavetopol, but was treacherously killed during the siege of Baku (1806). - When managing gr. Gudovich and Tormasov, Mingrelia, Abkhazia and Imeretia were annexed, and the exploits of Kotlyarevsky (the defeat of Abbas-Mirza, the capture of Lankaran and the conquest of the Talshinsky Khanate) contributed to the conclusion of the Gulistan Peace (October 12, 1813), the conditions of which changed after some acquisitions made by Mr.-l. Yermolov, commander-in-chief of Georgia since 1816.

All these wars, although they ended in rather important territorial acquisitions, had a harmful effect on the state of the national and state economy. In 1801-1804. state revenues collected about 100 million. annually, there were up to 260 m. of banknotes in circulation, the external debt did not exceed 47¼ million silver. rub., the deficit was negligible. Meanwhile, in 1810, incomes decreased two, and then four times. Banknotes were issued for 577 million rubles, the external debt increased to 100 million rubles, and there was a deficit of 66 million rubles. Accordingly, the value of the ruble has fallen sharply. In 1801-1804. the silver ruble accounted for 1¼ and 11/5 bank notes, and on April 9, 1812, 1 ruble was supposed to be considered. silver equal to 3 rubles. assig. The courageous hand of the former pupil of the St. Petersburg Alexander Seminary brought the state economy out of such a difficult situation. Thanks to the activities of Speransky (especially the manifestos of February 2, 1810, January 29 and February 11, 1812), the issuance of banknotes was discontinued, the per capita salary and quitrent tax were increased, a new progressive income tax, new indirect taxes and duties were established. The monetary system is also converted to the manifest. dated June 20, 1810. The results of the transformations were already partly reflected in 1811, when revenues of 355 1/2 m. (= 89 m. silver), expenses extended only up to 272 m. p., arrears were 43 m., and debt 61 m. This entire financial crisis was caused by a series of difficult wars. But these wars, after the Peace of Tilsit, no longer absorbed all the attention of Emperor Alexander. Unsuccessful wars 1805-1807 instilled in him distrust of his own military abilities; he again turned his energies to internal transformative activity, especially since he now had such a talented assistant as Speransky. The project of reforms, drawn up by Speransky in a liberal spirit and bringing into a system the thoughts expressed by the sovereign himself, was carried out only to a small extent. Decree 6 Aug. 1809 promulgated the rules for the promotion to ranks in the civil service and on tests in the sciences for the production in the 8th and 9th grades of officials without university certificates. By the Manifesto of January 1, 1810, the former "permanent" council was transformed into a state council with legislative significance. "In the order of state institutions," the Council constituted "a class in which all parts of government in their main relations to legislation" were considered and through it ascended to the supreme imperial power. Therefore, "all laws, statutes and institutions in their primitive outlines were proposed and considered in the State Council and then, by the action of the sovereign power, proceeded to their intended fulfillment." The State Council was subdivided into four departments: the department of laws included everything that, in essence, was the subject of the law; The commission of laws was supposed to submit to this department all the original outlines of the laws drawn up in it. The Department of Military Affairs included "objects" of the ministries of the military and naval. The department of civil and spiritual affairs included the affairs of justice, the spiritual administration and the police. Finally, the department of state economy belonged to "objects of general industry, sciences, trade, finance, treasury and accounts." Under the State Council there were: a commission for the drafting of laws, a commission of petitions, and a state chancellery. Together with the transformation of the State Council by the manifesto of July 25, 1810, two new institutions were attached to the former ministries: the Ministry of Police and the General Directorate for the Audit of Public Accounts. On the contrary, the affairs of the Ministry of Commerce are distributed between the Ministries of the Interior and Finance, and the min. Commerce has been abolished. - Along with the reform of the central administration, transformations continued in the sphere of spiritual education. Candle income of the church, determined for the expenses for the construction of religious schools (1807), made it possible to increase their number. In 1809, a theological academy was opened in St. Petersburg and in 1814 - in the Sergius Lavra; in 1810 a corps of railway engineers was established, in 1811 the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum was founded, and in 1814 the Public Library was opened.

But the second period of transformative activity was disrupted by the new war. Soon after the Erfurt Convention, disagreements between Russia and France were revealed. By virtue of this convention, Emperor Alexander posted the 30,000th detachment of the allied army in Galicia during the Austrian war of 1809. But this detachment, which was under the command of Prince. S. F. Golitsyn, acted hesitantly, since Napoleon's obvious desire to restore or at least significantly strengthen Poland and his refusal to approve the convention on December 23. 1809, which protected Russia from such an increase, aroused strong fears on the part of the Russian government. The emergence of disagreements intensified under the influence of new circumstances. The tariff for 1811, issued on December 19, 1810, aroused Napoleon's displeasure. By the agreement of 1801, peaceful trade relations with France were restored, and in 1802 the trade agreement concluded in 1786 was extended for 6 years. But already in 1804 it was forbidden to bring any paper fabrics along the western border, and in 1805 duties were increased on some silk and woolen products in order to encourage local, Russian production. The government was guided by the same goals in 1810. The new tariff increased duties on wine, wood, cocoa, coffee and granulated sugar; foreign paper (except white under branding), linen, silk, woolen and similar products are prohibited; Russian goods, flax, hemp, bacon, flaxseed, sailing and flamme linens, potash and resin are subject to the highest selling duty. On the contrary, the importation of crude foreign products and the duty-free export of iron from Russian factories are allowed. The new tariff harmed French trade and infuriated Napoleon, who demanded that Emperor Alexander accept the French tariff and not accept not only English, but also neutral (American) ships in Russian harbors. Soon after the publication of the new tariff, the Duke of Oldenburg, the uncle of Emperor Alexander, was deprived of his possessions, and the sovereign's protest, circularly expressed on this occasion on March 12, 1811, remained without consequences. After these clashes, war was inevitable. Already in 1810, Scharnhorst assured that Napoleon had a plan of war against Russia ready. In 1811, Prussia entered into an alliance with France, then Austria. In the summer of 1812, Napoleon moved with the allied troops through Prussia and on June 11 crossed the Neman between Kovno and Grodno, with 600,000 troops. Emperor Alexander had military forces three times smaller; at their head were: Barclay de Tolly and Prince. Bagration in the Vilna and Grodno provinces. But behind this relatively small army stood the entire Russian people, not to mention individuals and the nobility of entire provinces, all of Russia voluntarily fielded up to 320,000 warriors and donated at least a hundred million rubles. After the first clashes between Barclay near Vitebsk and Bagration near Mogilev with the French troops, as well as Napoleon's unsuccessful attempt to enter the rear of the Russian troops and occupy Smolensk, Barclay began to retreat along the Dorogobuzh road. Raevsky, and then Dokhturov (with Konovnitsyn and Neverovsky) succeeded in repelling Napoleon's two attacks on Smolensk; but after the second attack, Dokhturov had to leave Smolensk and join the retreating army. Despite the retreat, Emperor Alexander left without consequences Napoleon's attempt to start peace negotiations, but was forced to replace Barclay, who was unpopular among the troops, with Kutuzov. The latter arrived at the main apartment in Tsarevo Zaimishche on August 17, and on the 26th he fought the battle of Borodino. The outcome of the battle remained unresolved, but the Russian troops continued to retreat to Moscow, the population of which was strongly agitated against the French, among other things, posters gr. Rastopchina. The military council in Fili on the evening of September 1st decided to leave Moscow, which was occupied by Napoleon on September 3rd, but soon (October 7th) was abandoned due to a lack of supplies, severe fires and a decline in military discipline. Meanwhile, Kutuzov (probably on the advice of Tolya) turned off the Ryazan road, along which he was retreating, to Kaluga and gave the battles to Napoleon at Tarutin and Maloyaroslavets. Cold, hunger, unrest in the army, a quick retreat, the successful actions of the partisans (Davydov, Figner, Seslavin, Samus), the victories of Miloradovich at Vyazma, Ataman Platov at Vopi, Kutuzov at Krasnoye led the French army into complete disorder, and after the disastrous crossing of the Berezina forced Napoleon, before reaching Vilna, to flee to Paris. On December 25, 1812, a manifesto was issued on the final expulsion of the French from Russia. The Patriotic War was over; she made a strong change in the spiritual life of Emperor Alexander. In a difficult time of national disasters and spiritual anxieties, he began to seek support in a religious feeling and in this respect found support in the state. secret Shishkov, who now occupied a place that had been vacant after Speransky's removal before the start of the war. The successful outcome of this war further developed in the sovereign faith in the inscrutable ways of Divine Providence and the conviction that the Russian tsar had a difficult political task: to establish peace in Europe on the basis of justice, the sources of which the religious soul of Emperor Alexander began to look for in the gospel teachings. Kutuzov, Shishkov, partly c. Rumyantsev was against the continuation of the war abroad. But Emperor Alexander, supported by Stein, firmly resolved to continue military operations. January 1, 1813 Russian troops crossed the border of the empire and ended up in Prussia. Already on December 18, 1812, York, the head of the Prussian detachment sent to help the French troops, entered into an agreement with Dibich on the neutrality of the German troops, although, however, he did not have permission from the Prussian government to do so. The Treaty of Kalisz (February 15-16, 1813) concluded a defensive-offensive alliance with Prussia, confirmed by the Treaty of Teplitsky (August 1813). Meanwhile, the Russian troops under the command of Wittgenstein, together with the Prussians, were defeated in the battles of Lutzen and Bautzen (April 20 and May 9). After the armistice and the so-called Prague Conferences, which resulted in Austria entering into an alliance against Napoleon under the Reichenbach Convention (June 15, 1813), hostilities resumed. After a successful battle for Napoleon at Dresden and unsuccessful at Kulm, Brienne, Laon, Arsis-sur-Aube and Fer Champenoise, Paris surrendered on March 18, 1814, the Peace of Paris was concluded (May 18) and Napoleon was overthrown. Soon after, on May 26, 1815, the Congress of Vienna opened, mainly to discuss the questions of Polish, Saxon and Greek. Emperor Alexander was with the army throughout the campaign and insisted on the occupation of Paris by the allied forces. According to the main act of the Congress of Vienna (June 28, 1816), Russia acquired part of the Duchy of Warsaw, except for the Grand Duchy of Poznań, given to Prussia, and the part ceded to Austria, and in the Polish possessions annexed to Russia, a constitution was introduced by Emperor Alexander, drawn up in a liberal spirit. The peace negotiations at the Congress of Vienna were interrupted by Napoleon's attempt to seize the French throne again. Russian troops again moved from Poland to the banks of the Rhine, and Emperor Alexander left Vienna for Heidelberg. But the hundred-day reign of Napoleon ended with his defeat at Waterloo and the restoration of the legitimate dynasty in the person of Louis XVIII under the difficult conditions of the second Peace of Paris (November 8, 1815). Desiring to establish peaceful international relations between the Christian sovereigns of Europe on the basis of brotherly love and the gospel commandments, Emperor Alexander drew up an act of the Holy Alliance, signed by himself, the King of Prussia and the Austrian Emperor. International relations were maintained by congresses in Aachen (1818), where it was decided to withdraw the Allied troops from France, in Troppau (1820) about the unrest in Spain, Laibach (1821) - in view of the indignation in Savoy and the Neapolitan revolution, and, finally, in Verona (1822) - to pacify the indignation in Spain and discuss the Eastern question.

A direct result of the difficult wars of 1812-1814. was the deterioration of the state economy. By January 1, 1814, only 587½ million rubles were listed in the parish; internal debts reached 700 million rubles, the Dutch debt extended to 101½ million guilders (= 54 million rubles), and the silver ruble in 1815 went for 4 rubles. 15 k. assign. How long these consequences were, reveals the state of Russian finances ten years later. In 1825, state revenues were only 529½ million rubles, banknotes were issued for 595 1/3 million rubles, which, together with the Dutch and some other debts, amounted to 350½ million rubles. ser. It is true that in trade matters more significant successes are noticed. In 1814, the import of goods did not exceed 113½ million rubles, and the export - 196 million rubles; in 1825 the importation of goods reached 185½ mil. rub., the export extended to the amount of 236½ mil. rub. But the wars of 1812-1814. had other consequences as well. The restoration of free political and commercial relations between the European powers also caused the publication of several new tariffs. In the tariff of 1816, some changes were made in comparison with the tariff of 1810; and the new tariff of 1822 marked a return to the former protective system. With the fall of Napoleon, the established relationship between the political forces of Europe collapsed. Emperor Alexander took over the new definition of their relationship. This task diverted the attention of the sovereign from the internal transformative activities of previous years, especially since the throne at that time was no longer the former admirers of English constitutionalism, and the brilliant theoretician and adherent of French institutions Speransky was replaced over time by a stern formalist, chairman of the military department of the State Council and the chief head of military settlements, Count Arakcheev, poorly gifted by nature. However, in the government orders of the last decade of the reign of Emperor Alexander, traces of former reformative ideas are sometimes still visible. On May 28, 1816, the project of the Estonian nobility on the final emancipation of the peasants was approved. The Courland nobility followed the example of the Estonian nobles at the invitation of the government itself, which approved the same project for the Courland peasants on August 25, 1817 and for the Livland peasants on March 26, 1819. Together with estate orders, several changes were made in the central and regional administration. By decree of September 4, 1819, the Ministry of Police was attached to the Ministry of the Interior, from which the Department of Manufactories and Domestic Trade was transferred to the Ministry of Finance. In May 1824, the affairs of the Holy Synod were separated from the Ministry of Public Education, where they were transferred according to the manifesto of October 24, 1817, and where only the affairs of foreign confessions remained. Even earlier, a manifesto on May 7, 1817 established a council of credit institutions, both for auditing and verifying all operations, and for considering and concluding all assumptions on the credit part. By the same time (manif. April 2, 1817) was the replacement of the farming system with state-owned wine sales; management of drinking fees is concentrated in state chambers. Concerning the regional administration, an attempt was also made soon after that to distribute the Great Russian provinces into governor-generals. Government activity also continued to affect the care of public education. In 1819, public courses were organized at the St. Petersburg Pedagogical Institute, which laid the foundation for St. Petersburg University. In 1820 r. the engineering school was transformed and an artillery school was founded; The Richelieu Lyceum was founded in Odessa in 1816. Schools of mutual learning began to spread according to the method of Bel and Lancaster. In 1813, the Bible Society was founded, to which the sovereign soon issued a significant financial allowance. In 1814 the Imperial Public Library was opened in St. Petersburg. Individuals followed the lead of the government. Gr. Rumyantsev constantly donated money for the printing of sources (for example, for the publication of Russian chronicles - 25,000 rubles) and scientific research. At the same time, journalistic and literary activity developed strongly. As early as 1803, a "periodical essay on the successes of public education" was published under the Ministry of Public Education, and the St. Petersburg Journal (since 1804) was published under the Ministry of the Interior. But these official publications were by no means as important as they were: Vestnik Evropy (since 1802) by M. Kachenovsky and N. Karamzin, Son of the Fatherland by N. Grech (since 1813), Notes of the Fatherland by P. Svinin (since 1818), Siberian Bulletin by G. Spassky (1818-1825), Northern Archive by F. Bul Garin (1822-1838), who later joined the "Son of the Fatherland". The publications of the Moscow Society of History and Antiquities, founded in 1804, were distinguished by their scholarly character. ("Proceedings" and "Chronicles", as well as "Russian Memorabilia" - since 1815). At the same time, V. Zhukovsky, I. Dmitriev and I. Krylov, V. Ozerov and A. Griboedov acted, the sad sounds of Batyushkov's lyre were heard, the mighty voice of Pushkin was already heard and Baratynsky's poems began to be printed. Meanwhile, Karamzin was publishing his "History of the Russian State", and A. Schletser, N. Bantysh-Kamensky, K. Kalaidovich, A. Vostokov, Evgeny Bolkhovitinov (Metropolitan of Kiev), M. Kachenovsky, G. Evers were engaged in the development of more specific issues of historical science. Unfortunately, this intellectual movement was subjected to repressive measures, partly under the influence of the unrest that took place abroad and resonated to a small extent in the Russian troops, partly due to the more and more religiously conservative direction that the sovereign's own way of thinking was taking. On August 1, 1822, all sorts of secret societies were banned; in 1823, it was not allowed to send young people to some of the German universities. In May 1824, Admiral A. S. Shishkov, a well-known adherent of old Russian literary traditions, was entrusted with the management of the Ministry of Public Education; from the same time, the Bible Society ceased to meet and censorship conditions were significantly constrained.

Emperor Alexander spent the last years of his life for the most part in constant traveling to the most remote corners of Russia, or in almost complete solitude in Tsarskoye Selo. At this time, the Greek question was the main subject of his concern. The uprising of the Greeks against the Turks, caused in 1821 by Alexander Ypsilanti, who was in the Russian service, and the indignation in the Morea and on the islands of the Archipelago provoked a protest from Emperor Alexander. But the Sultan did not believe the sincerity of such a protest, and the Turks in Constantinople killed many Christians. Then the Russian ambassador, bar. Stroganov, left Constantinople. War was inevitable, but, delayed by European diplomats, it broke out only after the death of the sovereign. Emperor Alexander † November 19, 1825 in Taganrog, where he accompanied his wife, Empress Elisaveta Alekseevna, to improve her health.

In the attitude of Emperor Alexander to the Greek question, the peculiarities of that third stage of development, which the political system created by him experienced in the last decade of his reign, were quite clearly affected. This system initially grew up on the soil of abstract liberalism; the latter was replaced by political altruism, which in turn was transformed into religious conservatism.

The most important works on the history of Emperor Alexander I: M. Bogdanovich,"History of Emperor Alexander I", VI vol. (St. Petersburg, 1869-1871); S. Solovyov,"Emperor Alexander the First. Politics - diplomacy" (St. Petersburg, 1877); A. Hadler,"Emperor Alexander the First and the idea of the Holy Union" (Riga, IV vol., 1885-1868); H. Putyata,"Review of the life and reign of Emperor Alexander I" (in the "Historical collection." 1872, No. 1, pp. 426-494); Schilder,"Russia in its relations to Europe in the reign of Emperor Alexander I, 1806-1815." (in Rus. Star., 1888); N. Varadinov,"Histor. Ministry of Internal Affairs" (parts I-III, St. Petersburg, 1862); A. Semenov,"Study of historical information about Russian trade" (St. Petersburg, 1859, part II, pp. 113-226); M. Semevsky,"The Peasant Question" (2 volumes, St. Petersburg, 1888); I. Dityatin,"Organization and management of cities in Russia" (2 volumes, 1875-1877); A. Pypin,"Social movement under Alexander I" (St. Petersburg, 1871).

(Brockhaus)

(1777-1825) - ascended the throne in 1801, son of Paul I, grandson of Catherine II. Grandmother's favorite, A. was brought up "in the spirit of the 18th century," as this spirit was understood by the then nobility. In the sense of physical education, they tried to stay "closer to nature", which gave A. temper, very useful for his future camp life. As for education, it was entrusted to Rousseau's countryman, the Swiss La Harpe, a "republican", so, however, tactful that he did not get into any clashes with the court nobility of Catherine II, that is, with the serf landowners. From La Harpe A. got the habit of "republican" phrases, which again helped a lot when it was necessary to show off their liberalism and win over public opinion. In essence, A. was never a Republican or even a Liberal. Flogging and execution seemed to him natural means of control, and in this respect he surpassed many of his generals [an example is the famous phrase: "Military settlements will be, even if the road from St.

Catherine had in mind to bequeath the throne directly to A., bypassing Paul, but she died without having time to formalize her desire. When Paul came to the throne in 1796, A. found himself in relation to his father in the position of an unsuccessful applicant. This immediately had to create unbearable relations in the family. Pavel suspected his son all the time, rushed about with a plan to plant him in a fortress, in a word, at every step the story of Peter and Alexei Petrovich could be repeated. But Pavel was incomparably smaller than Peter, and A. was much larger, smarter and more cunning than his ill-fated son. Alexei Petrovich was only suspected of a conspiracy, while A. really organized conspiracies against his father: Pavel fell victim to the second of them (March 11/23, 1801). A. personally did not take part in the murder, but his name was given to the conspirators at the decisive moment, and his adjutant and closest friend Volkonsky was among the killers. Parricide was the only way out in the current situation, but the tragedy of March 11 still had a strong impact on A.'s psyche, partly preparing the mysticism of his last days.

A.'s policy was determined, however, not by his moods, but by the objective conditions of his accession to the throne. Pavel persecuted and persecuted the big nobility, the court servants of Catherine hated by him. A. in the early years relied on the people of this circle, although he despised them in his soul ("these insignificant people" - it was once said about them to the French envoy). Aristocratic constitution, which sought to "know", A., however, did not give, deftly playing on the contradictions within the "nobility". In his foreign policy, he followed her lead completely, concluding an alliance against Napoleonic France with England, the main consumer of the products of noble estates and the main supplier of luxury goods for large landowners. When the alliance led to the double defeat of Russia, in 1805 and in 1807, A. was forced to make peace, thereby breaking with the "nobility". A situation was emerging that was reminiscent of the last years of his father's life. In St. Petersburg "they talked about the assassination of the emperor, as they talk about rain or good weather" (report of the French ambassador Caulaincourt to Napoleon). A. tried to hold on for several years, relying on that layer, which was later called "raznochintsy", and on the industrial bourgeoisie, which was rising, thanks to the break with England. A former seminarian connected with bourgeois circles, the son of a rural priest, Speransky became state secretary and, in fact, first minister. He drafted a bourgeois constitution, reminiscent of the "fundamental laws" of 1906. But the severance of relations with England was, in fact, equal to the cessation of all foreign trade and placed against A. the main economic force of the era - merchant capital; the newborn industrial bourgeoisie was still too weak to serve as a support. By the spring of 1812, A. surrendered, Speransky was exiled, and the "nobility", in the person of the one created - formally according to the project of Speransky, but in fact from social elements hostile to the latter - state council returned to power again.

The natural consequence was a new alliance with England and a new break with France - the so-called. "patriotic war" (1812-14). After the first setbacks of the new war, A. almost "retired to private life." He lived in St. Petersburg, in the Kamennoostrovsky Palace, almost never showing up anywhere. “You are not in any danger,” his sister (and at the same time one of his favorites) Ekaterina Pavlovna wrote to him, “but you can imagine the situation of a country whose head is despised.” The unforeseen catastrophe of Napoleon's "great army", which lost 90% of its composition in Russia from hunger and frost, and the subsequent uprising of central Europe against Napoleon, radically changed A.'s personal position in the most unexpected way. On March 31, 1814, at the head of the allied armies, A. solemnly entered Paris - there was no person in Europe more influential than he. It might have made a stronger head spin; A., being neither a fool nor a coward, like some of the last Romanovs, was nevertheless a man of average mind and character. He now seeks above all to maintain his position of power in the West. Europe, not realizing that he got it by accident and that he played the role of a tool in the hands of the British. To this end, he seizes Poland, seeks to make it a springboard for a new campaign of Russian armies at any moment to the west; in order to ensure the reliability of this bridgehead, he courts the Polish bourgeoisie and the Polish landlords in every possible way, gives Poland a constitution, which he violates every day, inciting against himself both the Poles with his insincerity, and the Russian landowners in whom. The "Patriotic" war greatly raised nationalist sentiments - with its clear preference for Poland. Feeling his ever-increasing alienation from Russian "society", in which non-noble elements played an insignificant role at that time, A. tries to rely on people "personally devoted", which turn out to be, ch. arr., "Germans", that is, Baltic and partly Prussian nobles, and from the Russians - a rude soldier Arakcheev, by origin almost the same plebeian as Speransky, but without any constitutional projects. The crowning of the building was to be the creation of a uniform oprichnina, a special military caste, represented by the so-called. military settlements. All this terribly teased both the class and national pride of the Russian landowners, creating a favorable atmosphere for a conspiracy against A. himself - a conspiracy much deeper and more serious politically than the one that ended his father on March 11/23, 1801 . The plan for the murder of A. had already been completely worked out, and the moment of the murder was scheduled for maneuvers in the summer of 1826, but on November 19 (December 1) of the previous 1825, A. unexpectedly died in Taganrog from a malignant fever, which he contracted in the Crimea, where he traveled, preparing a war with Turkey and the capture of Constantinople; the realization of this dream of all the Romanovs, starting with Catherine, A. hoped to end his reign brilliantly. However, it was his younger brother and heir, Nikolai Pavlovich, who had to carry out this campaign without capturing Constantinople, who also had to lead a more "national" policy, abandoning too broad Western plans. From the nominal wife, Elizaveta Alekseevna, A. had no children - but he had countless of them from his constant and random favorites. According to his friend Volkonsky, mentioned above (not to be confused with the Decembrist), A. had connections with women in every city where he stayed. As we saw above, he did not leave alone the women of his own family, being in the closest relationship with one of his own sisters. In this respect, he was the real grandson of his grandmother, who counted the favorites in dozens. But Catherine until the end of her life retained a clear mind, while A. in recent years showed all the signs of religious insanity. It seemed to him that the "Lord God" interfered in all the little things of his life, he was brought to religious tenderness even, for example, by a successful review of the troops. On this basis, there was his rapprochement with the well-known religious charlatan Mrs. Krudener(cm.); In connection with these sentiments of his, there is also the form that he gave to his dominance over Europe - the formation of the so-called. Holy Union.

Lit.: Non-Marxist literature: Bogdanovich, M.N., History of the reign of Alexander I and Russia in his time, 6 vols., St. Petersburg, 1869-71; Schilder, N. K., Alexander I, 4 vols., St. Petersburg, 2nd ed., 1904; his own, Alexander I (in the Russian Biographical Dictionary, vol. 1); b. led. Prince Nikolai Mikhailovich, Emperor Alexander I, ed. 2, St. Petersburg; his own, Correspondence of Alexander I with his sister Ekaterina Pavlovna, St. Petersburg, 1910; his own, Count P. A. Stroganov, 3 vols., St. Petersburg, 1903; his own, Empress Ekaterina Alekseevna, 3 vols., St. Petersburg, 1908; Schiemann, Geschichte Russlands unter Kaiser Nicolaus I, B. I. Kaiser Alexander I und die Ergebnisse seiner Lebensarbeit, Berlin. 1901 (this entire first volume is devoted to the era of A. I); Schiller, Histoire intime de la Russie sous les empereurs Alexandre et Nicolas, 2 v., Paris; Mémoires du prince Adam Czartorysky et sa correspondance avec l "empereur Alexandre I, 2 t., P., 1887 (there is a Russian translation, M., 1912 and 1913). Marxist literature: Pokrovsky, M. H., Russian history from ancient times, vol. III (several editions); his own, Alexander I (History of Russia of the 19th century, ed. Granat , vol. 1, pp. 31-66).

M. Pokrovsky. Dictionary of personal names

- (Αλέξανδρος) Greek Genus: male. Etymological meaning: Αλέξ "protector" / ανδρος "man", "man" Middle name: Alexandrovich Alexandrovna Female pair name: Alexandra Produced. forms: Alik, Sanya, Aleksasha, Sasha ... Wikipedia

Alexander I. Alexander I (1777, St. Petersburg 1825, Taganrog), emperor since 1801, from the Romanov dynasty. Emperor's son. He ascended the throne as a result of a palace coup. As a child, he was greatly influenced by his grandmother, the Empress, ... ... Moscow (encyclopedia)

- (Alexander, Αλέξανδρος), called the Great, the king of Macedonia and the conqueror of Asia, was born in Pella in 356 BC. He was the son of Philip II and Olympias and was raised by Aristotle. In his early youth, he already showed that courage and fearlessness, which ... Encyclopedia of mythology

Alexander- Pavlovich (17771825), emperor (since 1801), son of Paul I, ascended the throne as a result of a palace coup. At the beginning of his reign, he pursued a liberal policy aimed at preserving absolutism. In 1802 ministries and a committee were established... Encyclopedic reference book "St. Petersburg"

Alexander I. Portrait by F. Gerard. ALEXANDER I (1777-1825), Emperor of Russia from 1801. The eldest son of Emperor Paul I. At the beginning of his reign, he carried out reforms prepared by the Unspoken Committee and M.M. Speransky. Under his leadership, Russia in ... Illustrated Encyclopedic Dictionary

I (1777 1825) Russian emperor since 1801. The eldest son of Paul I. At the beginning of his reign, he carried out moderately liberal reforms developed by the Unofficial Committee and M. M. Speransky. In foreign policy, he maneuvered between Great Britain and France. In 1805 ... ... Big Encyclopedic Dictionary, Alexander Blok. The present collected works of A. Blok included the poet's works of art, his most significant literary-critical and journalistic articles, essays and selected materials from ...

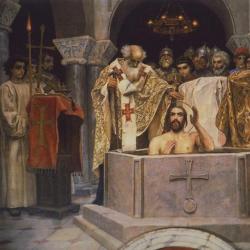

Alexander I

Emperor Alexander I.

Portrait by V.L. Borovikovsky from the original by E. Vigee-Lebrun. 1802.

Blessed

Alexander I Pavlovich Romanov (Blessed) (1777-1825) - Russian emperor from March 12 (24), 1801 - after the assassination of the emperor by conspirators from aristocratic circles Paul I.

Alexander I Pavlovich Romanov (Blessed) (1777-1825) - Russian emperor from March 12 (24), 1801 - after the assassination of the emperor by conspirators from aristocratic circles Paul I.

At the beginning of his reign, his domestic policy showed a desire for moderate liberalism. The necessary transformations were discussed by members of the Unspoken Committee - the "young friends" of the emperor. Ministerial (1802), Senate (1802), university and school (1802-1804) reforms were carried out, the State Council was created (1810), the Decree on free cultivators (1803), etc. was issued.

He went down in history as a skilled politician and diplomat. He sought to create multilateral European unions (see the Holy Alliance), widely used negotiations with politicians and monarchs of Europe at congresses and in personal meetings (see the Tilsit treaties of 1807).

His foreign policy was mainly dominated by the European direction. In the first years of his reign, he tried to maintain peaceful relations with the powers that fought for hegemony in Europe (France and England), but after the intensification of aggressive tendencies in the policy of Napoleon I, Russia became an active participant in the Third and Fourth anti-Napoleonic coalitions. As a result of the victory in the Russian-Swedish war of 1808-1809. The Grand Duchy of Finland was annexed to Russia. The defeat of Napoleon during the Patriotic War of 1812 and the foreign campaign of the Russian army in 1813-1814. strengthened the international prestige of Russia and Alexander I personally - by decision of the Vienna Congress of 1814-1815, in which the Russian Tsar was an active participant, most of the Polish lands (the Kingdom of Poland) were annexed to Russia.

Foreign policy in the eastern direction - the solution of the eastern issue - was expressed in support for national movements in the Balkans, the desire to annex the Danubian principalities and gain a foothold in Transcaucasia (see the Russian-Turkish war of 1806-1812, the Bucharest peace treaty of 1812, the Gulistan peace treaty of 1813).

The exchange of envoys in 1809 marked the beginning of Russian-American diplomatic relations.

Since 1815, a conservative trend has intensified in the foreign policy of Alexander I: with his consent, the Austrian troops suppressed the revolutions in Naples and Piedmont, and the French - in Spain; he took an evasive position in relation to the Greek uprising of 1821, which he considered as a speech by his subjects against the legitimate monarch (sultan).

Orlov A.S., Georgiev N.G., Georgiev V.A. Historical dictionary. 2nd ed. M., 2012, p. 11-12.

Other biographical material:

Persons:

Dolgorukov Petr Petrovich (1777-1806), prince, peer and close associate of Alexander I.

Elizaveta Alekseevna (1779-1826), Empress, wife of Emperor Alexander I.

Mordvinov Nikolai Semenovich (1754-1845), count, admiral.

Novosiltsev Nikolai Nikolaevich (1761-1836), personal friend of Alexander I.

Platov Matvey Ivanovich (1751 - 1818), cavalry general. Ataman.

Rostopchin Fedor Vasilievich (1763-1826), Russian statesman.

Speransky Mikhail Mikhailovich (1772-1839), prominent statesman.

Emperor Alexander at the Monk Seraphim of Sarov.

Salavat Shcherbakov. Moscow, Alexander Garden.

Literature:

Bezhin L. "LG-dossier" N 2, 1992.

Bogdanovich M. H., History of the reign of Alexander I and Russia in his time, vol. 1-6, St. Petersburg, 1869-1871;

Vallotton A. Alexander I. M. 1991.

Documents for the history of Russia's diplomatic relations with the Western European powers, from the conclusion of a general peace in 1814 to the congress in Verona in 1822. St. Petersburg. 1823. Vol. 1. Part 1. Vol. 2. 1825. -

Kizevetter A. A., Emperor Alexander I and Arakcheev, in the book: Historical essays, M., 1912;

Lenin, V.I. Works. T. IV. S. 337. -

Marx, K. and Engels, F. Works. T. IX. pp. 371-372, 504-505. T. XVI. Part II. S. 17, 21, 23, 24.-

Martens, F. F. Collection of treatises and conventions concluded by Russia with foreign powers. Vol. 2, 3, 4. Ch. 1.6.7, 11, 13, 14. St. Petersburg. 1875-1905. -

Martens, F. F. Russia and England at the beginning of the 19th century. "Bulletin of Europe". 1894. Prince. 10. S. 653-695. Book. 11. S. 186-223. -

Materials for the history of the Eastern question in 1808-1813 -

International politics of modern times in treaties, notes and declarations. Part 1. From the French Revolution to the Imperialist War. M. 1925. S. 61-136. -

Merezhkovsky D.S. Alexander the First M. "Armada", 1998.

Mironenko S. V. Autocracy and reforms: Political struggle in Russia at the beginning of the 19th century. M., 1989.

Nikolai Mikhailovich, leader prince. Emperor Alexander I. Experience of historical research. T. 1-2-SPb. 1912.-

Picheta, V.I. International policy of Russia at the beginning of the reign of Alexander I (until 1807). In book. "Patriotic war and Russian society". T. 1. M. . pp. 152-174.-

Picheta, V. I. Russia's International Policy after Tilsit. In book. "Patriotic war and Russian society". T. 2. M. . pp. 1-32. -

Pokrovsky M. H., Alexander I, in the book: History of Russia in the 19th century, ed. Pomegranate, v. 1, St. Petersburg, b. G.;

Popov, A. N. Patriotic War of 1812. Historical research. T. 1. Relations between Russia and foreign powers before the war of 1812. M. 1905. VI, 492 p. -

Presnyakov A. E., Alexander I, P., 1924;

Predtechensky A. V., Essays on socio-political. history of Russia in the first quarter. XIX century., M.-L., 1957.

Okun S. B., Essays on the history of the USSR. The end of the 18th - the first quarter of the 19th century, L., 1956;

Safonov M.M. The problem of reforms in the government policy of Russia at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. L., 1988.

Sakharov A. N. Alexander I // Russian autocrats (1801-1917). M., 1993.

Collection of the Russian Historical Society. T. 21, 70, 77, 82, 83, 88, 89, 112, 119, 121, 127. St. Petersburg. 1877-1908. -

Solovyov S. M., Emperor Alexander I. Politics - diplomacy, St. Petersburg, 1877;

Solovyov, S. M. Emperor Alexander I. Politics-diplomacy. Collected works. SPb. . S. 249-758 (there is a separate edition: SPb. 1877. 560 s). - Nadler, V. K. Emperor Alexander I and the idea of the Holy Alliance. T. 1-5. [Kharkiv]. 1886-1892. -

Stalin, I. V. On Engels' article "The Foreign Policy of Russian Tsarism". "Bolshevik". M. 1941. No. 9. S. 1-5.-

Suvorov N. On the history of the city of Vologda: On the stay in Vologda of royal persons and other remarkable historical persons // VEV. 1867. N 9. S. 348-357.

Troitsky N. A. Alexander I and Napoleon. M., 1994.

Fedorov V.A. Alexander I // Questions of history. 1990. No. 1;

Schilder, N.K. Emperor Alexander the First. His life and reign. Ed. 2. Vol. 1-4. SPb. 1904-1905.-

Czartoryski, A. Mémoires du prince Adam Czartoryski et correspondance avec l empereur Alexandre I-er. Pref. de M. Ch. De Mazade. T. 1-2. Paris. 1887. (Czartorizhsky, A. Memoirs of Prince Adam Czartorizhsky and his correspondence with Emperor Alexander I. T. 1-2. M .. 1912). -

Vandal, A. Napoleon et Alexandre I-er. L alliance russe sous le premier empire. 6th ed. T. 1-3. Paris. . (Vandal, A. Napoleon and Alexander I. The Franco-Russian Union during the First Empire. T. 1-3. St. Petersburg. 1910-1913). -

See also literature to the article The Congress of Vienna 1814 - 1815.

Scroll depicting a funeral procession

during the funeral of Emperor Alexander I (detail).

Russian emperor since 1801. The eldest son of Paul I. At the beginning of his reign, he carried out moderately liberal reforms developed by the Unofficial Committee and M. M. Speransky. In foreign policy, he maneuvered between Great Britain and France. In 1805-07 he participated in anti-French coalitions. In 1807-12 he temporarily became close to France. He waged successful wars with Turkey (1806-12) and Sweden (1808-09). Under Alexander I, the territories of Eastern Georgia (1801), Finland (1809), Bessarabia (1812), Azerbaijan (1813), and the former Duchy of Warsaw (1815) were annexed to Russia. After the Patriotic War of 1812, in 1813-14 he headed the anti-French coalition of European powers. He was one of the leaders of the Vienna Congress of 1814-15 and the organizers of the Holy Alliance.

ALEXANDER I, Emperor of Russia (1801-25), firstborn of Grand Duke Pavel Petrovich (later Emperor Paul I) and Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna.

Immediately after his birth, Alexander was taken from his parents by his grandmother, Empress Catherine II, who intended to raise him as an ideal sovereign, a successor to her work. On the recommendation of D. Diderot, the Swiss F. C. Laharpe, a republican by conviction, was invited to educate Alexander. The Grand Duke grew up with a romantic belief in the ideals of the Enlightenment, sympathized with the Poles who lost their statehood after the partitions of Poland, sympathized with the French Revolution and critically assessed the political system of the Russian autocracy. Catherine II forced him to read the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, and she herself explained to him its meaning. At the same time, in the last years of the grandmother's reign, Alexander found more and more inconsistencies between her declared ideals and everyday political practice. He had to carefully hide his feelings, which contributed to the formation in him of such traits as pretense and slyness. This was also reflected in the relationship with his father during a visit to his residence in Gatchina, where the spirit of the military and strict discipline reigned. Alexander constantly had to have, as it were, two masks: one for his grandmother, the other for his father. In 1793 he was married to Princess Louise of Baden (in Orthodoxy Elizaveta Alekseevna), who enjoyed the sympathy of Russian society, but was not loved by her husband.

It is believed that shortly before her death, Catherine II intended to bequeath the throne to Alexander, bypassing her son. Apparently, the grandson was aware of her plans, but did not agree to accept the throne.

After the accession of Paul, the position of Alexander became even more complicated, because he had to constantly prove his loyalty to the suspicious emperor. Alexander's attitude to his father's policy was sharply critical. It was these sentiments of Alexander that contributed to his involvement in a conspiracy against Paul, but on the condition that the conspirators save his father's life and would only seek his abdication. The tragic events of March 11, 1801 seriously affected the state of mind of Alexander: he felt guilty for the death of his father until the end of his days.

Alexander I ascended the Russian throne, intending to carry out a radical reform of the political system of Russia by creating a constitution that guaranteed personal freedom and civil rights to all subjects. He was aware that such a "revolution from above" would actually lead to the liquidation of the autocracy and was ready, if successful, to retire from power. However, he also understood that he needed a certain social support, like-minded people. He needed to get rid of pressure from both the conspirators who overthrew Paul and the “Catherine old men” who supported them. Already in the first days after the accession, Alexander announced that he would govern Russia “according to the laws and according to the heart” of Catherine II. On April 5, 1801, the Permanent Council was created - a legislative advisory body attached to the sovereign, which received the right to protest the actions and decrees of the king. In May of the same year, Alexander submitted to the council a draft decree banning the sale of peasants without land, but members of the Council made it clear to the emperor that the adoption of such a decree would cause unrest among the nobles and lead to a new coup d'état. After that, Alexander concentrated his efforts on developing a reform in the circle of his “young friends” (V.P. Kochubey, A.A. Czartorysky, P.A. Stroganov, N.N. Novosiltsev). By the time of Alexander’s coronation (September 1801), the Indispensable Council prepared a draft “Most Merciful Letter Complained to the Russian People”, which contained guarantees of the basic civil rights of subjects (freedom of speech, press, conscience, personal security, guarantee of private property, etc.), a draft manifesto on the peasant issue (banning the sale of peasants without land, establishing a procedure for buying peasants from the landowner) and a draft reorganization of the Senate. During the discussion of the drafts, sharp contradictions between the members of the Permanent Council were exposed, and as a result, none of the three documents was made public. It was only announced that the distribution of state peasants into private hands would be stopped. Further consideration of the peasant question led to the appearance on February 20, 1803 of the decree on “free cultivators”, which allowed the landowners to release the peasants to freedom and assign land to them as property, which for the first time created the category of personally free peasants.

In parallel, Alexander carried out administrative and educational reforms.