Josip Broz Tito: biography, personal life, family and children, politics, photos. Tito: tamer of the USSR, Yugoslavia and the West And other irresponsible comrades

Yugoslavia was torn apart by regional economic imbalances that 45 years of experimentation with a mixed economy had failed to resolve. Perhaps the federal republic was doomed from the very beginning, and in 1991 the process that began with the collapse of Austria-Hungary simply ended.

ELENA CHIRKOVA

The economic policies of Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito have been compared to those of Francisco Franco. One liberalized the planned economy, the other seriously limited the market. Both built a mixed economy, both are considered dictators, and both countries had strong separatist tendencies. Franco and Tito died almost at the same time - the first in 1975, the second in 1980, when global economic realities were approximately the same. Franco left behind a prosperous and united Spain. At the time of Tito's death, his country was at the end of its economic prosperity and soon collapsed.

The war in Europe officially ended in May 1945, but the liberation of Yugoslavia was completed only in October. Resistance leader Josip Broz Tito came to power in the country. At first, he was guided by the Soviet economic model.

Already in 1946, almost all industry was in the hands of the state. Nationalization was easy for the government, which consisted of members of the partisan movement - Tito's comrades-in-arms: many enterprises belonged to Italian and German capital and collaborators.

In 1949, the authorities set a course for collectivization of agriculture. In 1950, about 7 thousand peasant labor cooperatives were opened, each of which received more than two hectares of land. Attempts to create collective farms met fierce resistance from the peasants, even leading to uprisings. Tito did not take extreme measures; as a result, agriculture remained private, but the plot could not be more than 10 hectares. In addition, there were serious limitations in terms of mechanization. As a result, peasants had almost no equipment until the second half of the 1960s.

The planned economic system, copied from the Soviet one, operated in Yugoslavia until the late 1940s. In 1948, Tito broke up with Stalin. He wanted to remain independent from Moscow. In the Soviet Union, Josip Broz Tito was declared a revisionist, but Stalin did not fight his departure from the “general party line” through a military invasion. Evgeniy Matonin, the author of a biography of Tito in the ZhZL series, names among the possible reasons that the USSR did not invade Yugoslavia, the relatively small role of the Red Army in the liberation of Yugoslavia - the lack of "moral right", plus Stalin's attention was diverted by the war that began in Korea in 1950

Due to the threat of invasion, Tito eliminated the army's dependence on Soviet military supplies. Already in 1949, the Yugoslavs began producing their own fighter-bomber, the Ikarus S-49A, which was powered first by Soviet and then French engines, and by the mid-1950s, Yugoslav factories could fully supply the army with small arms, artillery and ammunition. The United States helped build the military-industrial complex of Yugoslavia, both with money and personnel. Subsequently, Josip Broz Tito will create the Non-Aligned Movement and will sell Yugoslav-made military products to member states, which will become one of the two “pillars” of the Yugoslav economic miracle of the 1960s. The second “whale”—Western loans—will be discussed below.

Between East and West

Soon, reforms began in the country aimed at strengthening the role of market relations in the economy. We started with self-government at enterprises. In 1950, a procedure was introduced whereby directors were elected by workers, but only from a list previously proposed to them. Workers were also allowed to set hiring rules, divide the small part of the profit that remained at the enterprise between the “investment” and “salary” items, and distribute the centrally established wage fund among categories of workers. Different sources give different shares of profit remaining at the disposal of enterprises, but in any case it was insignificant - from 5% to 20%. However, these measures also led to significant differentiation in wages.

The workers did not own any shares. All ownership of the companies' tangible and intangible assets remained state-owned. This meant that when fired, the worker lost his rights to everything. Economic science argues that theoretically this leads to underinvestment: the employee will prefer money today rather than investment and growth in the value of the company tomorrow. In practice, this was overcome precisely by the fact that the state itself allocated previously seized profits for investment purposes. The funds remaining with enterprises for capital investments were spent ineffectively: under the constant threat of confiscation of accumulated surpluses, they spent the money on anything and everything. Another consequence of self-management was workers' attempts to reduce staff numbers, which were criticized as anti-social actions.

Since 1952, state planning has been replaced by a regulated market and horizontal links between enterprises. In other words, enterprises themselves had to look for partners.

In the early 1950s, the card system still existed in Yugoslavia. In 1952, cards were abolished, and salaries began to be paid in cash. Prices were partially liberalized (and increased). They could be established by directive from the center, local authorities, be contractual, limited or free. Up to 80% of prices were regulated in one form or another, and approximately 65% of the textile industry - a seemingly ideal candidate for liberalization - fell under such control. The reforms also affected foreign trade: about 5% of enterprises received the right to trade freely with foreign countries, but they could not manage foreign currency earnings. Several dinar rates were introduced. Commercial law was gradually introduced, which even contained rules regulating the bankruptcy of enterprises.

The reforms involved a change in orientation from heavy industry to light industry; the main directions were housing construction and improving living standards. For example, an agreement was signed with Fiat on the creation of a car assembly plant in Yugoslavia. Several hundred construction projects of heavy industrial facilities were frozen.

The state retained centralized distribution of investment resources. The share of investment in GDP was high - about 34%, approximately equal to the level of the USSR. This article was financed by high taxes on businesses. Private business was allowed only small-scale - no more than five hired workers. Private could be, for example, a taxi or a restaurant.

Reforms accelerated in the mid-1960s. Enterprises sharply increased the share of profits remaining at their disposal, which led to a further increase in differentiation in wages. The role of the state in financing capital investments has been reduced. It was decided that banks would become the main source of investment resources, and their share in investment financing increased from 3% in 1960 to 50% in 1970. Interest rates were very low, negative in real terms in most cases. But negative interest rates create the wrong incentives: resources are wasted on ineffective projects. A situation that provokes a non-market distribution of credit funds gives rise to corruption. At the same time, there is an economic explanation for negative interest rates - reformers came up with the idea that banks should have the legal form of credit unions and be controlled by debtors. This system of ownership of the country's banking sector is one of the causes of inflation.

During the pricing reform of 1965, domestic prices were brought up to world prices, but then, however, they were frozen. Foreign trade was significantly liberalized and import tariffs were reduced.

From success to collapse

The Yugoslav economy showed impressive growth until the late 1970s. From 1952 to 1979, GDP increased by 6% per year, and per capita consumption by 4.5%. Between 1956 and 1970, living standards tripled. Yugoslavia has become a consumer society.

However, half-hearted and contradictory reforms led to the accumulation of imbalances. Thus, in 1953-1960 the trade deficit was 3% of GDP. The situation improved due to transfers from Yugoslavs who went to work abroad. For example, $1.3 billion in 1971 and $2.1 billion in 1972.

During Tito's time, people were allowed to emigrate and also to travel freely. In total, more than a million Yugoslavs went abroad to work; unemployment contributed to the outflow of labor. In the 1960s, the post-war baby boom generation began to enter the market, but the economy was unable to absorb such a volume of labor. Unemployment increased from 6-9% in the 1960s and early 1970s to 12-14% by the late 1970s. And if previously it was mostly observed among unskilled workers in rural areas, now qualified personnel in cities, including people with a university degree, have become closely acquainted with unemployment. In 1980, the national average was 13.8%, while in Slovenia - 1.4%, Bosnia and Herzegovina - 16.6%, Kosovo - 39.4%. By 1990, unemployment in Slovenia reached 4.7%, Bosnia and Herzegovina - 20.6%, in Kosovo it decreased slightly (see graph), and ten years later in Slovenia it was 7%, in Bosnia and Herzegovina - 40.1 %.

Self-government at enterprises created distortions in the labor market: workers in successful enterprises with high wages resisted accepting labor from unfavorable industries. This has led to wage gaps for the same professions in different industries, which are not typical even for Western countries. For example, in the scientific literature you can find the following data: the ratio of wages for workers with the same qualifications was 1.5 to 1 for the richest and poorest industries in the 1950s and 2.3 after the 1965 reform, despite the fact that the standard ratio in a market economy, approximately 1.6 to 1. The dispersion of wages within the sector was also large: in 30% of industries it exceeded 3 to 1, while the Western standard is 1.5 to 1.

Almost no new businesses opened. A private owner could not do this by law, and the state focused on developing and maintaining what exists. Bankruptcies were theoretically possible, but the government supported unprofitable production by diverting resources to them. It is believed that in the late 1970s, approximately 20-30% of enterprises were unprofitable and employed 10% of the country's labor force.

There was always inflation in Yugoslavia, but under Tito it was kept under control. In the 1950s it was no more than 3% per year, in the 1960s - about 10%, in the 1970s - slightly less than 20%. Price growth accelerated sharply after the death of Josip Broz Tito in 1980 - up to 40% per year until 1983, and then became completely uncontrollable. In 1987 and 1988, inflation reached triple digits, and in 1989 it developed into four-digit hyperinflation.

Yugoslav socialism was special also because it did not rely 100% on the bayonets of the Red Army

Although transfers from Yugoslav guest workers grew very quickly, they were no longer enough to plug the hole in the balance of payments. They started borrowing. Since 1961, external debt began to increase. It grew from almost zero base, but at a high average rate of about 18% per year for 30 years. At first, the loan was given willingly, including for political reasons: Tito deftly maneuvered between capitalist countries and the Eastern Bloc - Western leaders believed that Yugoslavia could be broken away from the socialist camp.

In 1991, Yugoslavia's external debt reached $20 billion (about $56 billion in today's terms) with a GDP of $120 billion. Debt as a percentage of GDP was small, but the import-intensive economy depended on increasing volumes of credit. In the early 1980s, the river of credit began to lose strength. It became difficult to take out debt; creditors understood that the loan was being “consumed”: it was used not so much for the development of export-oriented industries, but for maintaining the standard of living. Of course, industrial goods were also purchased, but the main share was in energy and raw materials, that is, in those material resources whose use cannot increase labor productivity.

In the 1970s, a shift away from the reforms of the 1950s and 1960s began. One of the reasons is considered to be the strengthening of the influence of “business executives” as a result of reforms - they opposed the party elite, which wanted to return power. In particular, the share of income that remained at the enterprise decreased again, prices began to be regulated more strictly: in 1970, prices for two-thirds of all goods and services were free, and in 1974 - only for a third. The departure from a market economy was accompanied by the consequences of the oil shock.

The imbalance between exports and imports, which also existed in the 1950s and 1960s, grew: the trade deficit grew from about 10% of GDP in 1971 to almost 50% in 1980. The country did not have stable sources of foreign exchange earnings, except for tourism and arms export/re-export, that is, there were not enough sources for loan repayment. In addition, in the early 1980s, economic growth stopped, and in 1986, GDP began to fall.

The IMF called on the federal government to change economic policy taking into account external debt, in particular to cut wages and reduce public consumption. But there was no leader of Tito’s caliber in the country who could decide to take such unpopular steps. Instead, the government chose non-market measures: they devalued the dinar by a quarter (in 1982), introduced restrictions on imports, taxes on travel abroad, limited the withdrawal of currency from bank accounts, and began to regulate fuel consumption. They decided to stimulate exports through loans, that is, emissions and accelerating inflation. The rejection of market reforms led to economic collapse and the collapse of the country.

Attempts to develop a plan for reforming the Soviet economy under Nikita Khrushchev were made with a clear eye on the experience of the Yugoslav comrades

Poor vs rich

Let's look at the expenses of the federal budget of Yugoslavia in 1990: financing the army - 45.5% (in 1991 - 49.5%), economic transfers (subsidizing agriculture, covering losses in case of bank failure and tax refunds) - 24%, pensions for World War II veterans - 8%, federal administration - 9%, financing of backward republics - 4.6%, social programs - 1.7%.

Almost half of the federal budget was spent on the army. In other words, economically strong republics (Slovenia and Croatia) paid the federal center to suppress separatist sentiments in them, and also sponsor backward regions. The official doctrine stated that after the collapse of the Warsaw bloc, aggression from Western countries was possible, but, as history has shown, the army became an instrument to pacify the rebellious republics.

Slovenia and Croatia were the first to declare independence, in June 1991. The economic motives are clear. Slovenia was a republic with full employment and even a labor shortage (only recently the standard of living there began to decline). For her, the costs of liberalization and technological modernization were the lowest.

The Yugoslav Federal Army attacked Slovenia the day after independence, an attack called the Ten Day War. Ten days later the army left Slovenia and entered Croatia. The war ended with a political victory for Slovenia and Croatia - they officially gained independence, and Slovenia did so even without serious bloodshed. The President of Yugoslavia, Slobodan Milosevic, quickly agreed to its secession, because he himself was going to build Greater Serbia, and few Serbs lived in Slovenia. Milosevic was ready to let Croatia go if it abandoned Slavonia and Krajina, populated predominantly by Serbs, and here the conflict became protracted. In 1992, the federal army supported the Bosnian Serbs in a conflict with Bosnian Muslims, leading to an even bloodier scenario than in Croatia. It is believed that the war ended completely only in 1995. 100 thousand people were killed, 2.5 million lost their homes.

By 1997, all former Yugoslav republics showed a decline in GDP per capita relative to the last peaceful year, except Slovenia, where GDP grew by 5%. The biggest disadvantage, almost twice as large, came from Serbia and Montenegro. In Bosnia and Herzegovina the decline was “only” 26%, partly due to strong population outflows. As Evgeniy Matonin writes in his biography of Tito, “after the collapse of Yugoslavia, inscriptions appeared more than once on the walls of houses: “The mechanic was better!” (a mechanic was Tito’s first profession).”

Slovenia, long a part of Austria-Hungary and accustomed to the German order, turned out to be the most economically successful among the republics of the former Yugoslavia. It lost most of the Yugoslav market, but was able to redirect exports to Germany and other EU countries. Slovenia's per capita GDP in 2013, according to the IMF, amounted to $28.5 thousand, here it overtook Greece and Portugal. According to the Forbes rating, Slovenia ranks first in the world in terms of personal freedom. Croatia is also quite successful, despite starting from a lower position due to the three-year war. GDP per capita in 2013 - $20.2 thousand.

In 2013, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, GDP per capita was $9.6 thousand, in Kosovo - $8.9 thousand. So, the rich republics failed to get ahead in terms of GDP growth: now GDP per capita in Bosnia is 33.7 % of the level of Slovenia, in 1990 the ratio was almost the same - 34.5%.

But that's not where the rich win. Developed regions have been feeding backward ones for almost 40 years: for example, in the first half of the 1970s, Slovenia received a transfer from the federal development fund amounting to less than 1% of its GDP, and Kosovo received approximately 50% of its own. Croatia provided 40% of the country's foreign exchange earnings, but could only keep 7% for itself. This did not equalize the level of economic development; it was only possible to smooth out current consumption. For example, the gap between Kosovo and Slovenia in terms of GDP per capita was fivefold in 1955, but became eightfold by the end of the 1980s. With the collapse of the country, GDP ceased to be redistributed, which was reflected in the standard of living and consumption. Rich regions no longer feed poor ones.

This is how the collapse of Yugoslavia differed from the history of the USSR: in Yugoslavia, the most developed regions wanted to secede so as not to feed the backward ones. Economic rationalism still prevailed over nationalism, although the latter was in abundance. In Belovezhskaya Pushcha, the collapse of the USSR was also supported by the poorest republics, although from the standpoint of economic rationalism they should have spoken out against it. Another illogical feature of the collapse of the USSR is that it passed quietly. Yegor Gaidar in his book “The Death of an Empire” noted that territorially integrated empires, where the colonies are not separated from the metropolis by sea (such as Austria-Hungary), do not disintegrate peacefully. The collapse of Austria-Hungary was accompanied by the First World War. The collapse of Yugoslavia and the subsequent separation of Kosovo into a separate state can be considered a kind of pre-disintegration of Austria-Hungary.

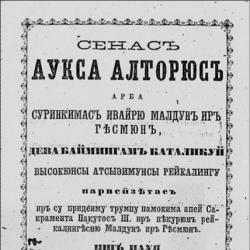

Tito () Josip () President of Yugoslavia since 1953, Marshal (.). Since 1937 he headed the Yugoslav Communist Party. After the attack on Yugoslavia by Germany and its allies in 1941, Tito headed the Supreme Headquarters of the People's Liberation... ... Encyclopedic Dictionary of World History

Broz Tito, Josip This term has other meanings, see Tito (meanings). Josip Broz Tito Serbo-Croat. Josip Broz, Josip Broz ... Wikipedia

Serbohorv. Josip Broz, Josip Broz Josip Broz Tito in 1971 ... Wikipedia

TITO, JOSIP BROZ (Tito, Josip Broz) JOSIP BROZ TITO (1892 1980), President of Yugoslavia. Born on May 25, 1892 in the village. Kumrovec in the northwestern part of Croatia, in a peasant family. In 1913, Tito was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian army, where he received the rank... ... Collier's Encyclopedia

Tito, Josip- Josip Tito. TITO (Broz Tito) Josip (1892 1980), President of Yugoslavia from 1953, Marshal (1943). From 1937 he headed the Yugoslav Communist Party [from 1940 general secretary of the party, in 1952 66 general secretary of the Central Committee of the Union... ... Illustrated Encyclopedic Dictionary

Tito Josip Broz- (Tito, losip Broz) (1892 1980), Yugoslav state. activist, Croatian by origin. Premier min. (1945 53), president (1953 80). During the 1st World War he served in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. army and ended up in Russia as a prisoner of war, escaped and participated in the Rus... ... The World History

TITO (Broz Tito) Josip (1892 1980) President of Yugoslavia since 1953, Chairman of the President of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia since 1971, Marshal (1943). In 1915 he ended up in Russia as a prisoner of war. Since September 1920 in his homeland, in... ...

Tito, Broz Tito (Broz Tito) Josip (b. 25.5.1892, Kumrovec, Croatia), leader of the Yugoslav and international labor movement, statesman and political figure of the SFRY, marshal (1943), twice People's Hero of Yugoslavia (1944, 1972), Hero … … Great Soviet Encyclopedia

Broz Tito (1892 1980), President of Yugoslavia from 1953, Chairman of the Presidium of the SFRY from 1971, Marshal (1943). In 1915 he ended up in Russia as a prisoner of war. Since September 1920 in his homeland, in the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPYU). Since 1934 in the leadership of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. In 1935 36 in... ... encyclopedic Dictionary

- (1892-1980), President of Yugoslavia from 1953, Chairman of the Presidium of the SFRY from 1971, Marshal (1943). In 1915 in Russia (prisoner of war). Since September 1920 at home and in the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPYU). In 193536 in Moscow, he worked at the Comintern. From December 1937 to... ... Big Encyclopedic Dictionary

Books

- Josip Broz Tito, Matonin E.. The first complete biography in Russian of Josip Broz Tito - the founder and long-term leader of socialist Yugoslavia, the most famous and at the same time the most mysterious world...

- Josip Broz Tito, Matonin Evgeniy Vitalievich. The first complete biography in Russian of Josip Broz Tito - the founder and long-term leader of socialist Yugoslavia, the most famous and at the same time the most mysterious world...

May 7 marks the 120th anniversary of the birth of the long-time leader of Yugoslavia, Josip Broz Tito. He skillfully maneuvered between the USSR and the West, resisting Stalin's wrath and building his own version of socialism. He united very different peoples, sometimes hating each other, in one country. He held Yugoslavia with an iron fist, and without him it collapsed with a roar.

He, the seventh child in the family, was born on May 7, 1892 in the village of Kumrowiec in Austria-Hungary. Today it stands on the very border of Croatia and Slovenia. As a matter of fact, the politician’s mother was Slovenian, her father was Croatian. True, there is a version that he was in fact a baptized Jew. Some argue that he was Czech on his father's side. Legends and rumors about the origin often haunt great personalities. What's there to be surprised about?

His name at birth was Josip Broz. Tito is a pseudonym that he received at the age of 42. Rumor has it that the origin of the nickname was this. He loved to lead too much. I told one: “you do it”! To the other - “you do this”! "You are that." It sounds like this in both Russian and Serbo-Croatian. Under this nickname he entered world history, becoming one of the brightest figures of the twentieth century and a living symbol of a united socialist Yugoslavia.

But it was later that he became the leader. Before that I had a very poor youth. He graduated from only five classes, in 1907-1913 he worked as a mechanic, first at factories in Zagreb and Ljubljana, then at automobile factories in Austria and Germany. He was a mechanic from God - he was even invited to take part in auto racing. Who knows - if he had not gotten into the whirlpool of political events, he would have developed a career as a racing driver. And so fate brought him to a completely different steppe.

Probably, the need that he experienced in his youth turned into his craving for luxury. In the relatively small area of Yugoslavia, he had over 30 residences - some by the sea, some in the mountains. Emperor Haile Selissie of Ethiopia, visiting Tito on the island of Brijuni in the Adriatic Sea, exclaimed: “They live like royalty here!” World cinema stars also came to see him there - Gina Lollobrigida, Elizabeth Taylor. He had an affair with some actresses - for example, with the Soviet screen star Tatyana Okunevskaya.

Tito's personal life is the stuff of legends. He was a professional seducer; no one has accurately calculated the number of his women. He was married three times. His first wife was the Russian noblewoman Pelageya Denisovna Belousova. The second (albeit with a common-law wife) is half-German, half-Slovenian Bertha Haas. His third and last wife, Serbian Jovanka Budisavljevic, has lived with him for the last 38 years, trying to actively participate in politics. Tito had three children - two sons and a daughter.

But the real main love, the real main business of Tito’s life was still politics. At the age of 18, he joined the ranks of the Social Democratic Party of Croatia and Slavonia. In 1914, as a non-commissioned officer in the army of Austria-Hungary, Josip Broz went to the First World War. A year later he was captured by Russians. Subsequently, it was in Russia that he finally became interested in the communist idea, even fighting as part of the Red Army on the fronts of the Civil War in 1918-1920.

In 1920, he returned to his homeland, and even marrying a Russian noblewoman did not shake his communist beliefs. The Communist Party in Yugoslavia (until 1929 - in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes; SHS) was banned, and Broz, working at various enterprises in Croatia, created underground organizations there. He was arrested several times and in 1929 he was sentenced to more than five years in prison.

But among his fellow fighters he quickly became an unquestioned authority. In the hierarchy of the still underground Communist Party of Yugoslavia, by 1927 he had risen to the position of secretary of the city organization in the largest city of Croatia, Zagreb. Upon his release, he joined the leadership of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. In 1935-1936. he worked in the Yugoslav section of the Comintern in Moscow, and in 1937 he returned to his homeland and headed the party instead of Milan Gorkić, who fell into the millstone of Stalin’s repressions. And until his death he did not let go of the reins of the party.

We must give Tito his due: he was not an armchair, but quite a combat leader of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia during the Second World War. There were several attempts on his life, but he survived. In the spring of 1941, German, Italian, Hungarian and Bulgarian occupiers entered the country. In his native Croatia, a puppet Independent State of Croatia (ISC) allied with Hitler appeared. And already in the summer of 1941 he managed to raise the first mass uprising in Europe against the Nazis.

People of various nationalities gathered around Tito. And this was his advantage over other anti-fascists - primarily the Chetniks, who relied on the Serbian national idea. Entire regions continually came under the control of communist partisans. Germany was forced to maintain dozens of divisions in Yugoslavia. In the end, it was Tito, and not bourgeois figures, who were recognized by both the USSR, the USA and Great Britain as the leading political force in Yugoslavia.

The fighters of the People's Liberation Army of Yugoslavia (NOLA) led by him, together with the Red Army, liberated Belgrade and Zagreb, but other cities and villages were liberated without Soviet help. This circumstance made Tito more independent from the USSR than other communist leaders. He independently won the right to lead the revived country. The leaders of other future socialist countries could not boast of this. That’s why he didn’t fawn over Joseph Stalin.

Ultimately, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, things came to an open confrontation between the USSR and Yugoslavia. Stalin did not tolerate the obstinate Tito, made attempts to remove him, but could not shake his power. As a result, Yugoslavia became “not a completely socialist country” that maintains good relations with the West, although it is not its ally. And from this intermediate position between socialism and capitalism, Tito derived many benefits.

The "intermediate" position of Yugoslavia manifested itself in a variety of areas. In economics, this consisted in the fact that there were no collective farms in the country, and enterprises had workers’ self-government. True, this self-government was very limited. Real power was in the hands of the secretaries of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (as Tito called his party in defiance of the USSR). So there is no need to talk about capitalism. True, since the 60s, Yugoslavs have had the opportunity to travel to Western Europe to work and have savings in freely convertible currency.

In the field of foreign policy, Yugoslavia was one of the pillars of the Non-Aligned Movement. In some cases it was in solidarity with the West, in others - with the USSR. Thus, Tito condemned the aggression of England, France and Israel against Egypt in 1956, but at the same time spoke out sharply against the introduction of Soviet troops into Czechoslovakia 12 years later. Relations with the Soviet Union ceased to be hostile, but Tito retained freedom of maneuver and was not a member of either the Warsaw Pact or the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance.

Today, a lengthy and interesting publication about Churchill, Tito and the myths associated with them appeared on the BBC website. It's called like this:

Strange myths about Churchill in Serbia: what are they based on.

“In Serbia, as in many other countries, they love all kinds of conspiracy theories. At the same time, for some unknown reason, strange stories about Winston Churchill are very popular among Serbs.

... Some of them are over 100 years old, but they are united by one theme - Churchill's possible connections with Serbia and Yugoslavia."

Unlike authors - historians, I do not have the task of spreading myths. Therefore, I will express my point of view about the activities of Joseph Broz Tito, Secretary of the Communist Party and President of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Tito is a strange figure and an interesting personality in world politics. However, like many communist masons, members of the International.

For example, where could a rural guy become so trained that, being already a marshal, he could speak at least 10 languages, had good aristocratic manners, was an erudite person, played the piano well and even fenced.

Many Serbs believe that he was an agent of the Vatican and Britain, and was responsible not only for the introduction of communism in Yugoslavia, but also for its collapse. By analogy with Ulyanov-Lenin in Soviet Russia, he granted the right to self-determination to the republics of Yugoslavia, even to the point of secession. This was enshrined in the 1974 Constitution.

And he fought all his life in the same way against “Serbian nationalism,” just as his comrades in Russia fought against “Great Russian chauvinism.”

In particular, after the war, he prohibited Serbs who fled the war in 1941 from returning to Kosovo and Metohija.

Tito reduced the territory of Serbia and separated two autonomies from the country - Vojvodina and Kosovo. And the Serbian lands of Baranja, Istria, Dalmatia and almost the entire coast of the Adriatic Sea along with the islands join the Croatian Republic.

More than 300,000 young Albanians are moving from Albania to Kosovo and Metohija, and more than 200,000 Serbs are being prohibited from returning.

Let me remind my Russian readers that in exactly the same way, only earlier, the Bolsheviks completely destroyed the Semirechensk and Ural Cossacks. And on their lands from Verny to Chelyabinsk they created the so-called republic. "Kazakhstan". Tito's communists had someone to follow as an example.

Tito's government in Serbia prohibited any religious gathering, and Serbian bishops were imprisoned (for example, Metropolitan Arsenij of Montenegro and Bishop Varnava Nastic). The communists did the same thing with Orthodox churches and monasteries as in Soviet Russia.

At the same time, in Catholic Croatia and Muslim enclaves there was no persecution of believers.

It was the same in Soviet Russia: Orthodox and Muslim believers were spread rot - but for some reason Jews and synagogues were not touched.

Joseph Broz systematically reduced the Serbian population to reduce his influence and presence in government by creating artificial nations and republics. Fortunately, there was someone to follow as an example!

Based on this policy, after the end of World War II in 1945, two new peoples were proclaimed - Montenegrins and Macedonians. ( Ukrainians And Belarusians).

For centuries, Montenegrins positioned themselves as Serbs from the Black Mountain, and Macedonians were Southern Serbs for more than a thousand years.

And in 1965 the third newly formed people are “Muslims” (!!!).

And all together the peoples, including artificial ones, began to be called “Yugoslavs”.

Just like all our peoples were “Soviet”, and now they have changed their colors and become “Russian”.

I consider another crime of Tito to be appropriating the merits of others. As you know, Belgrade was liberated by the commander of the 4th Mechanized Tank Corps, Vladimir Ivanovich Zhdanov.

Joseph Broz appeared in the Serbian capital only a few days later, and took credit for the victory. And we must be realistic and simply decent people, and finally admit that Yugoslavia was liberated by Marshal Fedor Ivanovich Tolbukhin.

And not the semi-mythical partisans, the “anti-fascist” communists of Joseph Broz Tito.

And we urgently need to restore order: The Russian people won the Second World War, not the “Soviet” people and not a semi-mythical multinationality.

The British granted their player Tito military and political legitimacy with the intention of preventing the Serbs from shaping a post-war order favorable to their national interests and challenging Serbian rights to self-determination.

An interesting symbiosis is between Josip Broz and Kurt Waldheim, a war criminal and murderer of Serbian children in the Battle of Kozara*, who would become the President of Austria after the war, and thanks to the support of Tito and Moscow, the UN Secretary General in 1971.

In 1961, Tito organized and joined the Non-Aligned Movement in order to thus prevent the spread of the Warsaw Bloc to Yugoslavia. This version is supported by the facts of unprecedented economic assistance to Yugoslavia provided by Britain and other countries participating in the NATO bloc.

And, concluding this publication, I will name only one reason for the popularity of Joseph Broz Tito both in NATO countries and among communists of all stripes, omitting many conspiracy theories.

For example, one that Tito was allegedly Churchill's illegitimate son.

The reason is that after World War II, NATO countries needed a reliable castle to block the Russians' access to the Mediterranean Sea. After all whoever controls the Mediterranean controls all of Europe. It is not for nothing that before “perestroika” there was such a powerful confrontation and there was a fierce struggle between the USSR and the USA for control of the sea.

And now, having neither its own bases, nor allies in the region, nor even its own Mediterranean squadron, the Russian Federation is trying to jump on the bandwagon of a train that has long departed.

note

* Operation in Northwestern Bosnia near Mount Kozara. The battle ended in the defeat of the Yugoslav troops and militias.

And it became notorious because of the Kozar massacre: during the battle, German fascists and Croatian Ustashes exterminated, according to various estimates, from 30 to 65 thousand civilians.

In the 1980s, a scandal erupted when documents were released showing former UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim had served in Yugoslavia in 1942 and participated in the massacre, although he had previously claimed that he was wounded in 1941 and did not return to the front. Moscow silently swallowed this bitter pill.

The phrase “We will never again live well as we lived under Tito!” popular throughout the former Yugoslavia. The permanent leader of the now defunct country in 1945-1980 was a Croatian by nationality, but is still terribly popular among residents of all the republics that were once part of the SFRY. In any ex-Yugoslav new state, which sometimes very bloodily achieved independence, it is easy to meet on the street a person wearing a souvenir T-shirt with the slogan: “Comrade Tito, come back! Muslims, Serbs and Croats love you. You gave us everything and stole nothing. And now they steal everything and give nothing!” Quite recently, in Bosnia (where the sad anniversary of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the civil war, which caused the death of 200 thousand people is being celebrated), a sociological survey was conducted, and it turned out that in the presidential elections, if Tito had been alive, 60 (!) percent of the population would have voted for him. Even teenagers born after the collapse of Yugoslavia told me: “But Tito is a fucking cool dude!” Both in Bosnia, and even in the Albanian-populated region of Kosovo, they say: if “comrade” Yugoslavia were ruled now, no one would even think of separating.

Celebrating the birthday of Josip Broz Tito in his home village of Kumrovec (Croatia). Photo: www.globallookpress.com

“Now Bosnia, Serbia, Kosovo, Macedonia are poor countries,” explains political scientist Alex Vadisevich. - Montenegro lives a little better, Croatia and Slovenia - although not bad, but in terms of economic development they are like the moon compared to the countries of Western Europe. And, of course, these states do not mean anything at all; they are considered either as puppets or as parasites who are constantly begging for loans and subsidies from the EU. Under Tito's rule, the economy of Yugoslavia was considered the best in the “socialist bloc”: young families were given free apartments, wages were stable and constantly increasing. It was in the Soviet Union that you had socialism that was harsh morally and materially, but here everything was simpler. Films with explicit erotic scenes were shown freely in cinemas, beaches were opened for nudists, anyone could travel to Germany or France without a visa, private shops and hairdressers operated: only large factories were state-owned. So people wonder why they swapped fudge for soap.”

Participants in events marking the 30th anniversary of the death of Josip Broz Tito. Belgrade, May 4, 2010. Photo: www.globallookpress.com

A merchant in Mostar is trying to persuade you to buy a portrait of Tito with the inscription: “Iosip Broz - dobar skroz” (loosely translated: “Josip Broz - with him even in the cold”). “He, you know, was as simple as the rest of us,” the store owner sighs dreamily. — He smoked like a locomotive, loved women: he married five times, and divorced with scandals. He put his last wife under house arrest: he accused him of preparing a coup d'etat, but in reality, according to rumors, he was jealous. Hot guy, a real Yugoslav. Today's politicians are trying to be American: with tense smiles, like castrated cats, in expensive suits, with hairstyles from the best stylists for three hundred euros. This same one was of our blood, a native of the people: he worked in Russia as a mechanic. Under him, our country was powerful and strong. Now it’s a dumping ground for the poor.”

Josip Broz Tito and his fifth wife Jovanka, 1962. Photo: www.globallookpress.com

It feels like he is persuading himself, and not a tourist, to buy. Every resident of Bosnia and Herzegovina, having learned that the guest is from Moscow, will definitely tell: so, Tito fought in the First World War for Austria-Hungary, he was captured, taken to Siberia, there he married a Russian, and fell in love with Russia with all his soul, then returned to Yugoslavia to make a socialist revolution. About Tito's quarrel with Stalin they try not to mention it: it spoils the overall good picture of the wonderful friendship between the SFRY and the USSR.

It seems that if another 25 years pass at this standard of living, the dead president will become more popular in the Balkans than Jesus Christ. In fact, let's be honest: the citizens of Bosnia miss the collapsed Yugoslavia, but they are simply unpleasant to admit it. Otherwise, why did hundreds of thousands of people fight and die? It is much more convenient to be nostalgic for Josip Broz Tito.