Galician Rus'. Galicia-Volyn principality: geographical location. Formation of the Galicia-Volyn principality Galician principality territory

Near Volhynia until the middle of the XII century. there was no own dynasty of princes. She, as a rule, was directly ruled from Kyiv, or at times Kyiv proteges sat at the Vladimir table.

The formation of the Galician principality began in the second half of the 11th century. This process is associated with the activities of the founder of the Galician dynasty, Prince Rostislav Vladimirovich, grandson of Yaroslav the Wise.

The heyday of the Galician principality falls on the reign of Yaroslav Osmomysl (1153-1187), who gave a decisive rebuff to the Hungarians and Poles who pressed on him and waged a fierce struggle against the boyars. With the death of his son Vladimir Yaroslavich, the Rostislavich dynasty ceased to exist, and in 1199 the Vladimir-Volyn prince Roman Mstislavich took possession of the Galician principality and united the Galician and Volyn lands into a single Galician-Volyn principality. Its center was Galich, then - Hill, and since 1272 - Lviv. The victorious campaigns of Roman's squads against Lithuania, Poland, Hungary and the Polovtsy created a high international prestige for him and the principality.

After the death of Roman (1205), the western lands of Rus' again entered a period of unrest and princely-boyar civil strife. The struggle of the feudal groupings of the western lands of Rus' reached its greatest acuteness under the young sons of Roman Mstislavich - Daniil and Vasilka.

The Galicia-Volyn principality broke up into destinies - Galicia, Zvenigorod and Vladimir. This made it possible for Hungary, where young Daniel was brought up at the court of King Andrew II, to constantly intervene in Galicia-Volyn affairs, and soon to occupy Western Russian lands. The boyar opposition was not so organized and mature as to turn the Galician land into a boyar republic, but it had enough strength to organize endless conspiracies and riots against the princes.

Shortly before the invasion of the hordes of Batu, Daniil Romanovich managed to overcome the opposition from the powerful Galician and Volyn boyars and in 1238 triumphantly entered Galich. In the struggle against the feudal opposition, the authorities relied on the squad, the city leaders and service feudal lords. The popular masses strongly supported Daniel's unifying policy. In 1239, the Galician-Volyn army captured Kiev, but the success was short-lived.

Hoping to create an anti-Horde coalition on a European scale with the help of the pope, Daniil Romanovich agreed to accept the royal crown offered to him by Innocent IV. The coronation took place in 1253.

during campaigns against the Lithuanian Yotvingians in the small town of Dorogichin near the western border of the principality. The Roman Curia turned their attention to Galicia and Volhynia, hoping to spread Catholicism in these lands. In 1264 Daniel Romanovich died in Kholm. After his death, the decline of the Galicia-Volyn principality began, which broke up into four destinies.In the XIV century. Galicia was captured by Poland, and Volhynia by Lithuania. After the Union of Lublin in 1569, the Galician and Volyn lands became part of a single multinational Polish-Lithuanian state - the Commonwealth.

Social system. A feature of the social structure of the Galicia-Volyn principality was that a large group of boyars was created there, in whose hands almost all land holdings were concentrated. However, the process of formation of large feudal landownership did not proceed in the same way everywhere. In Galicia, its growth outpaced the formation of a princely domain. In Volhynia, on the contrary, along with the boyar landownership, domain landownership received significant development. This is explained by the fact that it was in Galicia, earlier than in Volhynia, that the economic and political prerequisites for a faster growth of large-scale feudal landownership matured. The princely domain began to take shape when the predominant part of the communal lands was seized by the boyars and the range of free lands for princely possessions was limited. In addition, the Galician princes, in an effort to enlist the support of local feudal lords, gave them part of their lands and thereby reduced the princely domain.

The most important role among the feudal lords of the Galicia-Volyn principality was played by the Galician boyars - "Galician men". They owned large estates and dependent peasants. In the source

nicknames of the 12th century. the ancestors of the Galician boyars act as "princely husbands". The strength of this boyars, who were expanding the boundaries of their possessions and conducting large-scale trade, was constantly growing. Inside the boyars there was a constant struggle for land, for power. Already in the XII century. "Galician men" oppose any attempts to limit their rights in favor of princely power and growing cities.

Another group consisted of service feudal lords, whose sources of land holdings were princely grants, boyar lands confiscated and redistributed by princes, as well as unauthorized seizures of communal lands. In the overwhelming majority of cases, they owned the land conditionally while they served, i.e. for service and under the condition of service. Serving feudal lords supplied the prince with an army consisting of feudally dependent peasants. Galician princes relied on them in the fight against the boyars.

The ruling class of the Galicia-Volyn principality also included a large church nobility in the person of archbishops, bishops, abbots of monasteries and others, who also owned vast lands and peasants. Churches and monasteries acquired land holdings through grants and donations from princes. Often they, like princes and boyars, seized communal lands, and turned the peasants into monastic or church feudally dependent people.

The bulk of the rural population in the Galicia-Volyn principality were peasants. Both free and dependent peasants were called smerds. The prevailing form of peasant land ownership was communal, later called "dvorishche". Gradually, the community broke up into individual yards.

The process of formation of large land holdings and the formation of a class of feudal lords was accompanied by an increase in the feudal dependence of the peasants and the emergence of feudal rent. Labor rent in the 11th-12th centuries. gradually replaced by rent products. The size of feudal duties was established by the feudal lords at their own discretion.

The brutal exploitation of the peasants intensified the class struggle, which often took the form of popular uprisings against the feudal lords. Such a mass action of the peasants was, for example, an uprising in 1159 under Yaroslav Osmomysl.

Kholopstvo in the Galicia-Volyn principality survived, but the number of serfs decreased, many of them were planted on the ground and merged with the peasants.

In the Galicia-Volyn principality, there were over 80 cities, including the largest - Berestye (later Brest), Vladimir, Galich, Lvov, Lutsk, Przemysl, Kholm.

The most numerous group of the urban population were artisans. The cities housed jewelry, pottery, blacksmithing and glass-making workshops. They worked both for the customer and for the market, internal or external. Salt trade brought large incomes. Being a large commercial and industrial center, Galich quickly acquired the importance of a cultural center as well. The well-known Galicia-Volyn chronicle and other written monuments of the 12th-13th centuries were created in it.

Political system. A feature of the Galicia-Volyn principality was that for a long time it was not divided into destinies. After the death of Daniil Romanovich, it broke up into the Galician and Volyn lands, and then each of these lands began to split up in turn. Another peculiarity was that power, in essence, was in the hands of the big boyars.

Since the Galician-Volyn princes did not have a broad economic and social base, their power was fragile. She was inherited. The place of the deceased father was occupied by the eldest of the sons, whom the rest of his brothers were supposed to "honor in their father's place." A widow-mother enjoyed significant political influence with her sons. Despite the system of vassalage on which relations between members of the princely house were built, each princely possession was politically largely independent.

Although the princes expressed the interests of the feudal lords as a whole, nevertheless they could not concentrate the fullness of state power in their hands. The Galician boyars played a major role in the political life of the country. It even disposed of the princely table - it invited and dismissed the princes. The history of the Galicia-Volyn principality is full of examples when the princes, who lost the support of the boyars, were forced to leave their principalities. The forms of struggle of the boyars against objectionable princes are also characteristic. Against them they invited the Hungarians and Poles, put to death objectionable princes (this is how the Igorevich princes were hanged in 1208), removed them from Galicia (in 1226). There is such a case when the boyar Volodislav Kormilchich, who did not belong to the dynasty, proclaimed himself a prince in 1231. Often, representatives of the spiritual nobility were also at the head of the boyar rebellions directed against the prince. In such an environment, the

Chapter 5. Rus' in the period of feudal fragmentation

§ 3. Galicia-Volyn principality

The main support of the princes was the middle and small feudal lords, as well as the city leaders.

Galicia-Volyn princes had certain administrative, military, judicial and legislative powers. In particular, they appointed officials in cities and volosts, endowing them with land holdings under the condition of service, formally they were commanders-in-chief of all armed forces. But each boyar had his own military militia, and since the regiments of the Galician boyars often outnumbered the prince's, in case of disagreement, the boyars could argue with the prince, using military force. The supreme judicial power of the princes, in case of disagreements with the boyars, passed to the boyar elite. Finally, the princes issued charters concerning various issues of government, but they were often not recognized by the boyars.

The boyars exercised their power with the help of the council of the boyars. It consisted of the largest landowners, bishops and persons holding the highest government positions. The structure, the rights, the competence of council have not been defined.

The boyar council was convened, as a rule, at the initiative of the boyars themselves. The prince did not have the right to convene a council at will, could not issue a single state act without his consent. The council zealously guarded the interests of the boyars, intervening even in the family affairs of the prince. This body, not being formally the highest authority, actually controlled the principality. Since the council included the boyars, who held the largest administrative positions, the entire state apparatus of government was actually subordinate to it.The Galician-Volyn princes from time to time, under emergency circumstances, convened a veche in order to strengthen their power, but it did not have much influence. It could be attended by small merchants and artisans, but the top of the feudal lords played a decisive role.

Galicia-Volyn princes took part in all-Russian feudal congresses. Occasionally, congresses of feudal lords were convened, concerning only the Galicia-Volyn principality. So, in the first half of the XII century. a congress of feudal lords was held in the city of Sharts to resolve the issue of civil strife over volosts between the sons of the Przemysl prince Volodar, Rostislav and Vladimirk.

In the Galicia-Volyn principality, earlier than in other Russian lands, a palace and patrimonial administration arose. In the system of this administration, the court, or butler, played a significant role. He was in charge of basically all matters relating to the court.

prince, he was entrusted with the command of individual regiments, during military operations he guarded the life of the prince.

Among the palace ranks are mentioned a printer, a stolnik, a bowler, a falconer, a hunter, a stableman, etc. The printer was in charge of the prince's office, was the keeper of the prince's treasury, which at the same time was also the prince's archive. In his hands was the prince's seal. The stolnik was in charge of the prince's table, served him during meals, and was responsible for the quality of the table. Chashnich was in charge of side forests, cellars and everything related to supplying the prince's table with drinks. The falconer was in charge of bird hunting. The hunter was in charge of hunting the beast. The main function of the equerry was to serve the prince's cavalry. Numerous princely keykeepers acted under the control of these officials. The positions of butler, printer, steward, groom and others gradually turned into palace ranks.

The territory of the Galicia-Volyn principality was originally divided into thousands and hundreds. As the thousand and sotsky with their administrative apparatus gradually became part of the palace and patrimonial apparatus of the prince, the positions of voivodes and volostels arose instead of them. Accordingly, the territory of the principality was divided into voivodeships and volosts. Elders were elected in the communities, who were in charge of administrative and petty court cases.

Posadniks were appointed and sent directly to the cities by the prince. They not only possessed administrative and military power, but also performed judicial functions and collected tributes and duties from the population.

Right. The legal system of the Galicia-Volyn principality differed little from the legal systems that existed in other Russian lands during the period of feudal fragmentation. The norms of Russian Truth, only slightly modified, continued to operate here as well.

The Galician-Volyn princes issued, of course, their own acts. Among them, a valuable source characterizing the economic relations of the Galician principality with Czech, Hungarian and other merchants is the charter of Prince Ivan Rosti-Slavich Berladnik of 1134. It established a number of benefits for foreign merchants. Around 1287, the Manuscript of Prince Vladimir Vasilkovich was published, concerning the norms of inheritance law in the Vladimir-Volyn principality. The document says-

Chapter 5. Rus' in the period of feudal fragmentation

Xia about the transfer by Prince Vladimir of the right to exploit the feudally dependent population to the heirs. At the same time, it provides materials for studying the management of villages and cities. Around 1289, the Statutory Charter of the Volyn Prince Mstislav Daniilovich was issued, characterizing the duties that fell on the shoulders of the feudally dependent population of South-Western Rus'.

tttnChapter 6. MONGOLO-TATAR STATES

ON THE TERRITORY OF OUR COUNTRY

tttk During the period of fragmentation in Rus', the development of the early feudal state continues. Relatively centralized Ancient Rus' breaks up into a mass of large, medium, small and smallest states. In terms of their political forms, even small feudal estates are trying to copy the Kievan state.

During this period, a fundamentally new form of government appears - the republic. The Novgorod and Pskov feudal republics are widely known. Less well known is Vyatka, a colony of Novgorod that arose at the end of the 12th century. on the Mari and Udmurt lands, which became an independent state and existed until the end of the 15th century.1

All the considered feudal powers are united, in principle, by a single legal system, which is based on an epoch-making legal act - Russian Truth. Not a single principality creates a new law capable of at least to some extent replacing the Russian Truth. Only its new editions are being formed. Only in the feudal republics (and this is no coincidence) new major legislative acts arise.

The feudal fragmentation of Rus', as well as other regions of the country, was an inevitable stage in the development of the state. But this inevitability has cost our people dearly. In the XIII century. Mongol-Tatar hordes attacked Rus'.

To really understand history well, you need to mentally represent the era of interest, the spirit of its time and the main characters. Today we will make a short trip to medieval Rus' through the picturesque lands of Galicia and Volhynia.

What is it, Rus' of the 12th-13th centuries?

First of all, it is divided into small states, each of which lives according to its own laws and has its own ruler (prince). Such a phenomenon was called Rus. In each principality, people speak a certain dialect of the Russian language, which depends on the geographical location of the territory.

The structure of Rus' is also interesting. Historians distinguish two classes - the ruling elite, consisting of the nobility (influential boyars), and the estate of dependent peasants. For some reason, the latter always turned out to be much more.

Representatives of another class lived in large cities - artisans. These people had a remarkable ability to create authentic things. Thanks to them, woodcarving appeared, which is known not only in Russia, but also abroad. In a few words, we talked about medieval Rus', then there will be only the history of the Galicia-Volyn principality.

Lands that are part of the Principality

The young state, the development of which began under Roman Mstislavovich, consisted of different lands. What were these territories? The state included the Galician, Volyn, Lutsk, Polissya, Kholmsky, Zvenigorod and Terebovlya lands. As well as part of the territories of modern Moldova, Transcarpathia, Podolia and Podlasie.

Like various puzzles, these plots of land succinctly formed the Galicia-Volyn principality (the geographical location and neighboring countries of the young state will be described in the next chapter).

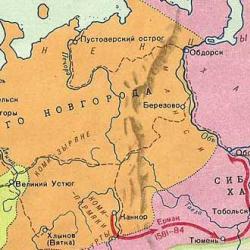

Principality location

On stretched Galicia-Volyn principality. The geographical position of the new association was obviously advantageous. It combined three aspects:

- location in the center of Europe;

- comfortable climate;

- fertile lands, invariably bringing good harvests.

A good location meant a variety of neighbors, but far from all of them were friendly to the young state.

In the east, the young tandem had a long border with Kiev and the Turov-Pinsk principality. Relations between the fraternal peoples were friendly. But the countries in the west and north did not particularly favor the young state. Poland and Lithuania always wanted to control Galicia and Volyn, which they eventually achieved in the 14th century.

In the south, the state was adjacent to the Golden Horde. Relations with the southern neighbor were always difficult. This is due to serious cultural differences and the presence of disputed territories.

Brief historical background

The Principality arose in 1199, under the confluence of two circumstances. The first was quite logical - the presence of two culturally close territories (Galicia and Volhynia) and unfriendly neighboring countries (the Kingdom of Poland and the Golden Horde) nearby. The second is the emergence of a strong political figure - Prince Roman Mstislavovich. The wise ruler was well aware that the larger the state, the easier it is for him to resist a common enemy, and culturally close peoples will get along in one state. His plan paid off, and at the end of the 12th century a new formation appeared.

Who weakened the young state? Natives of the Golden Horde were able to shake the Galicia-Volyn principality. The development of the state ended at the end of the 14th century.

Wise rulers

Over the 200 years of the existence of the state, different people have been in power. Wise princes are a real find for Galicia and Volhynia. So, who managed to bring calm and peace to this long-suffering territory? Who were these people?

- Yaroslav Vladimirovich Osmomysl, the predecessor of Roman Mstislavovich, was the first to come to the territories in question. He was able to successfully establish himself at the mouth of the Danube.

- Roman Mstislavovich - unifier of Galicia and Volhynia.

- Danila Romanovich Galitsky is the native son of Roman Mstislavovich. He again brought together the lands of the Galicia-Volyn principality.

Subsequent rulers of the principality were less strong-willed. In 1392, the Galicia-Volyn principality ceased to exist. The princes were unable to resist external opponents. As a result, Volyn became Lithuanian, Galicia went to Poland, and Chervona Rus - to the Hungarians.

Specific people created the Galicia-Volyn principality. The princes, whose achievements are described in this chapter, contributed to the prosperity and victories of the young state in the south-west of Rus'.

Relations with neighbors and foreign policy

Influential countries surrounded the Galicia-Volyn principality. The geographical position of the young state meant conflicts with neighbors. The nature of foreign policy strongly depended on the historical period and the specific ruler: there were bright campaigns of conquest, there was also a period of forced cooperation with Rome. The latter was carried out in order to protect against the Poles.

Conquests and Danila Galitsky made the young state one of the strongest in Eastern Europe. The unifying prince pursued a wise foreign policy towards Lithuania, the Kingdom of Poland and Hungary. He managed to extend his influence to Kievan Rus in 1202-1203. As a result, the people of Kiev had no choice but to accept a new ruler.

No less interesting is the political triumph of Danila Galitsky. When he was a child, chaos reigned in the territory of Volhynia and Galicia. But, having matured, the young heir followed in the footsteps of his father. Under Danil Romanovich, the Galicia-Volyn principality reappeared. The prince significantly expanded the territory of his state: he annexed the eastern neighbor and part of Poland (including the city of Lublin).

Unique culture

History impartially shows that each influential state creates its own authentic culture. That's how people recognize him.

The cultural features of the Galicia-Volyn principality are very diverse. We will consider the architecture of medieval cities.

Stone cathedrals and castles characterize the Galicia-Volyn region. The land was rich in similar buildings). In the 12th-13th centuries, a unique architectural school was formed in the lands of Galicia and Volhynia. She absorbed both the traditions of Western European masters and the techniques of the Kyiv school. Local craftsmen created such architectural masterpieces as the Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir-Volynsky and the Church of St. Panteleimon in Galich.

An interesting state in the south of Rus', the Galicia-Volyn principality, has gone down in history forever (we already know its geographical position for sure). A peculiar history and picturesque nature invariably attract lovers to explore the world.

It was formed in 1199 as a result of the unification by a descendant - Roman Mstislavich of the Vladimir-Volyn land and the city of Galich. At the time, the Galicia-Volyn principality was one of the most developed and largest principalities. It included about 9 lands and several territories of modern regions.

The princes of the Galicia-Volyn principality actively pursued foreign policy in central and eastern Europe. The main competitors, located in the vicinity of the principality, were the Polish and Hungarian kingdoms, the Polovtsy, and closer to the middle of the 13th century also from.

Mutual relations with Poland, Hungary and Lithuania

The Galicia-Volyn state, centered in Galich, fell under the rule of Poland and Hungary after the death of Roman Mstislavich in 1214. However, already in 1238 - 1264. The Galicia-Volyn principality regains strength and independence thanks to Mstislav the Udalny and the son of Roman Mstislavich - Daniel.

The social system of the Galicia-Volyn principality

The main feature of the social structure of the principality was that almost all land holdings there were in the power of a large group of boyars. An important role was played by the estates, they fought against the unfair, in their opinion, princely power, which tried to limit their rights in their favor. The other group included serving feudal lords. Most often, they owned land only while they were in the service. They provided the prince with an army, which consisted of peasants dependent on them. This was a support in the fight against the boyars for the Galician princes.

At the top of the feudal stairs was the church nobility. They owned vast lands and peasants. The main part of the rural population of the Galicia-Volyn principality were peasants. More than 80 different cities were located on the territory of the principality. Most of the urban population were artisans. There were many workshops here, and their products went to domestic and foreign markets. Salt trade also brought good income.

The state system of the Galicia-Volyn principality

Despite the power of the big boyars, the Galicia-Volyn principality retained its unity longer than the rest of the Russian lands. The Galician boyars were at the head, deciding who would sit at the princely table and who should be removed. They conducted their power with the help of the boyar council, which included large landowners, bishops and people of high state positions. Due to the fact that the boyars were in the council, it can be said with certainty that the entire state apparatus of government was in his power.

The princes of the Galicia-Volyn principality sometimes convened, but they did not have much influence, since there was a palace and patrimonial system of government.

The legal system of the principality practically did not differ from the system of other Russian lands. The effect of the norm (with minor changes) also extended to the territory of the Galicia-Volyn principality. The princes issued a number of normative acts that are worthy of mention, these are:

- Statutory charter of Ivan Berladnik (1134);

- Manuscript of Prince Vladimir Vasilkovich;

- Statutory charter of Mstislav Daniilovich (1289).

Prerequisites for the collapse of the Galicia-Volyn principality

Being in feudal dependence on the Golden Horde, relations between it and the Galicia-Volyn principality deteriorated sharply, the sons of Daniel led, this led to the weakening of the principality. The collapse of the Galicia-Volyn principality occurred due to the increased influence of Poland and Lithuania on it, as well as in connection with the simultaneous death of Leo and Andrei Yurievich in 1323. In 1339, the Principality of Galicia was completely captured by Poland, and in 1382, Poland and Lithuania divided Volhynia among themselves.

Essay

Galicia-Volyn principality

Introduction 3

1. Galicia-Volyn principality 4

2. Social order 5

3. State system 6

4. Political history of the Galicia-Volyn principality 7

Conclusion 12

References 14

Introduction

The Galicia-Volyn Principality was originally divided into two principalities - Galicia and Volyn. They were subsequently merged. Galician land is modern Moldova and Northern Bukovina.

In the south, the border reached the Black Sea and the Danube. In the west, the Galician land bordered on Hungary, which was located beyond the Carpathians. Rusyns lived in the Carpathians - Chervonnaya Rus. In the north-west, the Galician land bordered on Poland, and in the north - on Volhynia. Galician land in the east adjoined the Kyiv principality. Volyn occupied the region of the Upper Pripyat and its right tributaries. Volyn land bordered on Poland, Lithuania, Turovo-Pinsk principality and Galicia.

Both Galician and Volhynian lands were rich and densely populated. The soil was rich black soil. Therefore, agriculture has always flourished here. In addition, there were salt mines in Galicia. Table salt was also exported to Russian principalities and abroad.

Various crafts were well developed on the lands of the Galicia-Volyn principality. At that time there were about 80 cities on these lands. The main ones were Vladimir, Lutsk, Buzhsk, Cherven, Belz, Pinsk, Berestye in Volyn and Galich, Przemysl, Zvenigorod, Terebovl, Holm in Galicia. The capital of the Volyn land was the city of Vladimir.

The Galicia-Volyn principality traded with Byzantium, the Danubian countries, Crimea, Poland, Germany, the Czech Republic, and also with other countries. There was an active trade with other Russian principalities.

Merchants from different countries lived in the cities of the principality. They were Germans, Surozhians, Bulgarians, Jews, Armenians, Russians. The Galician land was the most developed in Ancient Rus'. Large landowners appeared here earlier than princes.

1. Galicia-Volyn principality

The southwestern Russian principalities - Vladimir-Volyn and Galicia - became part of Kievan Rus at the end of the 10th century, but the policy of the great Kiev princes did not receive recognition from the local landed nobility, and already from the end of the 11th century. the struggle for their isolation begins, despite the fact that Volhynia did not have its own princely dynasty and was traditionally associated with Kiev, which sent its governors.

The separation of the Galician principality was outlined in the second half of the 11th century, and its heyday fell on the reign of Yaroslav Osmomysl (gg.), who desperately fought against enemies - the Hungarians, Poles and his own boyars. In 1199, Vladimir-Volyn prince Roman Mstislavich conquered the Galician principality and united the Galician and Volyn lands into a single Galician-Volyn principality with a center in Galicia, and then in Lvov. In the XIV century. Galicia was captured by Poland, and Volhynia by Lithuania. In the middle of the XVI century. Galician and Volyn lands became part of the multinational Polish-Lithuanian state - the Commonwealth.

2. Social order

A feature of the social structure of the Galicia-Volyn principality was that a large group of boyars was formed there, in whose hands almost all land holdings were concentrated. The most important role was played by "Galician men" - large patrimonials, who already in the XII century. oppose any attempts to limit their rights in favor of princely power and growing cities.

The other group consisted of service feudal lords. The sources of their land holdings were princely grants, boyar lands confiscated and redistributed by the princes, as well as seized communal lands. In the vast majority of cases, they held the land conditionally while they served. Serving feudal lords supplied the prince with an army consisting of peasants dependent on them. It was the support of the Galician princes in the fight against the boyars.

The large church nobility, bishops, abbots of monasteries, who owned vast lands and peasants, also belonged to the feudal elite. The church and monasteries acquired land holdings at the expense of grants and donations from the princes. Often they, like princes and boyars, seized communal lands, turning the peasants into monastic and church feudal-dependent people. The bulk of the rural population in the Galicia-Volyn principality were peasants (smerdy). The growth of large landownership and the formation of a class of feudal lords were accompanied by the establishment of feudal dependence and the appearance of feudal rent. Such a category as serfs has almost disappeared. Serfdom merged with the peasants who were sitting on the ground.

In the Galicia-Volyn principality, there were over 80 cities. The most numerous group of the urban population were artisans. In the cities there were jewelry, pottery, blacksmith and other workshops, the products of which went not only to the domestic, but also to the foreign market. Salt trade brought large incomes. Being the center of crafts and trade, Galich gained fame as a cultural center. The Galician-Volyn chronicle was created here, as well as other written monuments of the 12th-14th centuries.

3. State system

The Galicia-Volyn principality, longer than many other Russian lands, maintained its unity, although the power in it belonged to the big boyars. The power of the princes was unstable. Suffice it to say that the Galician boyars disposed of even the princely table - they invited and removed the princes. The history of the Galicia-Volyn principality is full of examples when the princes, who lost the support of the top of the boyars, were forced to go into exile. To fight the princes, the boyars invited Poles and Hungarians. Several Galician-Volyn princes were hanged by the boyars.

The boyars exercised their power with the help of a council, which included the largest landowners, bishops and persons holding the highest government positions. The prince had no right to convene a council at will, could not issue a single act without his consent. Since the council included boyars who occupied major administrative positions, the entire state apparatus of government was actually subordinate to it.

The Galician-Volyn princes from time to time, under emergency circumstances, convened a veche, but it did not have much influence. They took part in all-Russian feudal congresses. Occasionally, congresses of feudal lords and the Galicia-Volyn principality were convened. In this principality, there was a palace-patrimonial system of government.

The territory of the state was divided into thousands and hundreds. As the thousand and sotsky with their administrative apparatus gradually became part of the palace and patrimonial apparatus of the prince, the positions of voivodes and volostels arose instead of them. Accordingly, the territory was divided into voivodeships and volosts. Elders were elected in the communities, who were in charge of administrative and petty court cases. Posadniks were appointed to cities. They possessed not only administrative and military power, but also performed judicial functions, collected tributes and duties from the population.

4. Political history of the Galicia-Volyn principality

After the death of Yaroslav, chaos began. His son Vladimir (), the last of the Rostislav dynasty, began to rule.

Soon the boyars rebelled against his authority, forcing him to flee to Hungary. The Hungarian king Andrei promised to return Vladimir to the throne, but, having come to Galicia, he proclaimed this land his. When popular uprisings began to explode against foreigners, Vladimir made peace with the boyars and expelled the Magyars.

Although Vladimir finally ascended the throne again, he became more dependent on the boyars than ever. This unfortunate episode became typical of what was often repeated over the next 50 years: a strong prince unites the lands; the boyars, fearing the loss of their privileges, give foreign countries a pretext for intervention; then chaos ensues, which continues until another powerful prince enters the arena and takes over the situation.

Although the offering of Galicia convincingly testified to the growing importance of the outskirts, its union with Volhynia promised to bring even more significant, even epoch-making consequences for the whole of Eastern Europe.

The person who carried out such an association was the Volyn prince Roman Mstislavich (). From his youth, he plunged into the political struggle. In 1168, when his father, Prince Mstislav of Volhynia, was competing with Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky of Suzdal for the throne of Kiev in the south, Roman was invited to reign in Novgorod to defend the city. In the north. In 1173, after the death of his father, Roman ascended the Volyn throne, resuming the gutted and neglected estates of his family. In 1199, he was able to unite Galicia with Volyn, creating a new majestic state on the political map of Eastern Europe, headed by an energetic, active and talented prince.

In domestic politics, Roman focused on strengthening princely power, that is, weakening the boyars, many of whom he sent into exile or executed. His favorite proverb was "If you don't kill the bees, you won't eat honey."

As in other European countries, the allies of the prince in the fight against the oligarchy were petty bourgeois and boyars. However, Roman's greatest fame came from his success in foreign policy. In 1203, having united Volhynia with Galicia, he defeated his rivals from Suzdal and captured Kiev. Consequently, all, with the exception of Chernigov, the Ukrainian principalities fell under the authority of one prince: Kiev, Pereyaslav, Galicia and Volyn.

It seemed that the unification of all the former Kyiv lands that make up the territory of modern Ukraine was about to happen. Considering how close Prince Roman came to the realization of this goal, modern Ukrainian historians give him a special place in their studies.

To protect the Ukrainian principalities, Roman conducted a series of unheard-of successful campaigns against the Polovtsy, at the same time he went far to the north into the Polish and Lithuanian lands. The desire to expand the boundaries of his already vast possessions was the cause of his death. In 1205, going through the Polish lands, Roman was ambushed and died. The territorial association that he created lasted only six years - too short a time for any stable political entity to crystallize out of it. And yet, Roman's contemporaries, in recognition of his outstanding achievements, called him "Great" and "ruler of all Rus'."

Soon after the death of Prince Roman, squabbles broke out again between the princes. Foreign intervention intensified - these three eternal misfortunes, which, in the end, ruined the state that he built it so tirelessly. His sons Daniil were only four, and Vasilko - two years old, and the Galician boyars drove them away along with their strong-willed mother, Princess Anna. Instead, they called three Igorevichs, the sons of the hero of The Tale of Igor's Campaign. For many boyars, this was a fatal mistake. Not wanting to share power with the oligarchy, the Igorovichi destroyed close to 500 boyars, until they were finally expelled (later the Galician nobility took revenge on them by hanging all three Igorovichi). Then the boyars did something unheard of - in 1213 they elected Prince Vladislav Kormilchich from their midst. Taking advantage of the indignation of these daring actions, the Polish and Hungarian feudal lords, supposedly protecting the rights of Daniel and Vasilko, captured Galicia and divided it among themselves. Under such circumstances, young Daniil and Vasilko began to "buy more" land that their father once owned. First of all, Daniel established himself in Volhynia (1221), where his dynasty continued to enjoy favor, both among the nobility and among the common people.

Only in 1238 he was able to regain Galich and part of Galicia. The following year, Daniel captured Kyiv and sent his thousandth Dmitry to defend the city from the Mongol-Tatars. Only in 1245, after a decisive victory in the battle of Yaroslav, did he finally conquer all of Galicia.

Thus, it took princely Daniel 40 years to return his father's possession. Having taken Galicia for himself, Daniil gave Volhynia to Vasilkov. Despite such a division, both principalities continued to exist as one under the superficiality of the older and more active Prince Daniel. Domestic policy Daniil, like his father, to counterbalance the boyars, passionately desired to secure support among the peasants and the bourgeoisie. He fortified many existing cities, and also established new ones, including in 1256 Lvov, named after his son Leo. To populate new city cells, Daniel invited artisans and merchants from Germany, Poland, as well as from Rus'. The multinational character of the Galician cities, which up to the XX century. remained their typical feature, strengthened by large Armenian and Jewish communities that, with the decline of Kyiv, came to the west. To protect the smerds from the arbitrariness of the boyars, special officers were appointed in the villages, military detachments were formed from the peasants.

The most serious foreign policy problem of Prince Daniel was the Mongol-Tatars. In 1241, they passed through Galicia and Volhynia, although they did not inflict such crushing destruction here as in other Russian principalities. However, the successes of the Romanovich dynasty attracted the attention of the Mongol-Tatars. Shortly after the victory at Yaroslav, Daniel receives a formidable order to appear at the Khan's court. In order not to incur the wrath of evil conquerors, he had nothing better than to submit. To a certain extent, Prince Daniel made a trip to the city in 1246.

Barn - Batiev's capital on the Volga - was successful. He was kindly accepted and that the most important was released alive. But the price of this was the recognition of the superficiality of the Mongol-Tatars. Batu himself underestimated this humiliating fact. Handing Danilov a goblet of sour koumiss, the Mongol-Tatars' favorite drink, he offered to get used to it, for "now you are one with us."

However, unlike the northeastern principalities, located in close proximity to the Mongol-Tatars and more dependent on their direct dikpape, Galicia and Volhynia were lucky to avoid such vigilant observation, their main duty to the new overlords was to provide auxiliary detachments during the Mongol Tatar attacks on Poland and Lithuania. At first, the influence of the Mongol-Tatars in Galicia and Volyn was so weak that Prince Daniel could pursue a fairly independent foreign policy, openly aimed at getting rid of Mongol domination.

Having established friendly relations with Poland and Hungary, Daniel turned to Pope Innocent IV with a request to help gather the Slavs for a crusade against the Mongol-Tatars. For this, Daniel agreed to the transfer of his possessions under the church jurisdiction of Rhyme. So for the first time he asked a question that would later become an important and constant theme of Galician history, namely, the question of the relationship between Western Ukrainians and the Roman Church. To encourage the Galician prince, the pope sent him a royal crown, and in 1253 in Dorogochin on Buza, the pope's envoy crowned Daniel as king.

However, the main concern of Prince Daniel was the organization of a crusade and other assistance from the West. All this, despite the assurance of the pope, he never managed to carry out. And yet, in 1254, Daniel launched a military campaign to recapture Kyiv from the Mongol-Tatars, whose main forces were far to the east. Despite the first successes, he failed to carry out his plan and also had to pay dearly for bad luck. In 1259, a large Mongol-Tatar army led by Burundai unexpectedly moved to Galicia and Volhynia. The Mongol-Tatars put the Romanovichs before a choice: either dismantle the walls of all fortified cities, leaving them unarmed and dependent on the mercy of the Mongol-Tatars, or face the threat of immediate destruction. With a stone in his heart, Daniel was forced to oversee the destruction of the walls that he so diligently brought down.

The bad luck of the anti-Mongolian policy did not lead to a weakening of the great influence that Daniil Galitsky corrected him on his western neighbors. Galicia enjoyed great prestige in Poland, especially in the Principality of Mazovia. That is why the Lithuanian prince Mindaugas (Mindovg), whose country was just beginning to rise, was forced to make territorial concessions to the Danilovs in Mazovia. In addition, as a sign of goodwill, Mindaugas had to agree to the marriage of his two children with the son and daughter of Prince Daniel. More actively than any other Galician ruler Daniel participated in the political life of Central Europe. Using marriage as a means of achieving foreign policy goals, he married his son Roman to the successor to the throne of Babenberz Gertrude and made an attempt, albeit unsuccessful, to put him on the Austrian ducal throne.

In 1264, after almost 60 years of political activity, Daniel died. In Ukrainian historiography, he is considered the most prominent of all the rulers of the western principalities. Against the backdrop of the difficult circumstances in which he had to operate, his achievements were truly outstanding. At the same time, with the renewal and expansion of his father's possessions, Daniel of Galicia held back the Polish and Hungarian expansion. Having overcome the power of the boyars, he succeeded in bringing the socio-economic and cultural level of his possessions to one of the highest in Eastern Europe. However, not all of his plans were successful. Danila failed to contain Kyiv, just as he failed to achieve his most important goal - to get rid of the Mongol-Tatar yoke. And yet he was able to reduce the pressure of the Mongol-Tatars to a minimum. Trying to isolate himself from influences from the East, Daniil turned to the West, thereby giving Western Ukrainians an example that they will inherit in all the following centuries.

For 100 years after Daniel's death, there were no particularly noticeable changes in Volhynia and Galicia. The stereotype of government established by princes Daniel and Vasilko - with an energetic and active prince in Galicia and a passive one in Volhynia - was inherited to a certain extent by their sons, Leo () and Vladimir () respectively. The ambitious and restless Leo was constantly embroiled in political conflicts. When the last of the Arpad dynasty died in Hungary, he seized Transcarpathian Rus, laying the foundations for future Ukrainian claims to the western slopes of the Carpathians. Leo was active in Poland, which "drowned" in internecine wars; he even sought the Polish throne in Krakow. Despite the aggressive policy of Leo, at the end of the XIII - at the beginning of the XIV century. Galicia and Volhynia experienced a period of relative calm as their western neighbors were temporarily weakened.

turned out to be the opposite of his Galician cousin, and tensions often arose between them. Unwilling to take part in wars and diplomatic activities, he focused on such peaceful affairs as the construction of cities, castles and churches. According to the Galician-Volyn chronicle, he was "a great scribe and philosopher" and spent most of his time reading and copying books and manuscripts. The death of Vladimir in 1289 upset not only his subjects, but also modern historians, because, obviously, the sudden end of the Galician-Volyn chronicle of the same year was associated with it. As a result, a large gap remained in the history of the western principalities, which covers the period from 1289 to 1340. All that is currently known about the events in Galicia and Volhynia in the last period of independent existence is reduced to a few random historical fragments.

After Leo's death, his son Yuri reigned in Galicia and Volhynia. He must have been a good ruler, since some chronicles note that during his peaceful reign these lands "bloomed in wealth and glory." The solidity of the position of Prince Leo gave him reason to use the title "King of Rus'". Dissatisfied with the decision of the Metropolitan of Kyiv to move his residence to Vladimir in the northeast, Yuri receives the consent of Constantinople to lay a separate metropolis in Galicia.

The last two representatives of the Romanovich dynasty were the sons of Yuri Andrei and Lev, who together ruled in the Galicia-Volyn principality. Concerned about the growing power of Lithuania, they entered into an alliance with the knights of the Teutonic Order. With regard to the Mongol-Tatars, the princes pursued an independent, even hostile policy; there are also reasons to believe that they died in the fight against the Mongols-Tatars.

When the last prince of the local dynasty died in 1323, the nobility of both principalities chose the Polish cousin of the Romanovichs, Bolesław Mazowiecki, to the throne. Having changed his name to Yuri and converted to Orthodoxy, the new ruler took over the continuation of the policy of his predecessors. Despite his Polish origin, he reconquered lands previously enthusiastic by the Poles, and also renewed his alliance with the Teutons against the Lithuanians. In domestic politics, Yuri Boleslav continued to support the cities and tried to expand his power. Such a course probably led to a fight with the boyars, who poisoned him in 1340, as if for an attempt to introduce Catholicism and connivance with foreigners.

So their own nobility deprived Galicia and Volhynia of the last prince. Since then, Western Ukrainians have fallen under the rule of foreign rulers.

For a hundred years after the fall of Kyiv, the Galician-Volyn principality served as a pillar of Ukrainian statehood. In this role, both principalities took over most of the Kievan inheritance and at the same time prevented the seizure of Western Ukrainian lands by Poland. Thus, at a turning point in history, they retained among the Ukrainians, or Russ, as they were now called, a sense of cultural and political identity. This feeling will be decisive for their existence as a separate national entity in the evil times that are coming.

Conclusion

As in Kievan Rus, the entire population of the Galicia-Volyn land was divided into free, semi-dependent (semi-free) and dependent.

The ruling social groups - the princes, the boyars and the clergy, part of the peasantry, most of the urban population - belonged to the free. The development of the princely domain in the Galician land had its own characteristics.

The difficulties of forming a princely domain in Galicia consisted, firstly, in the fact that it began to take shape already when most of the communal lands were seized by the boyars and the circle of free lands for princely possessions was limited. Secondly, the prince, in an effort to enlist the support of local feudal lords, gave them part of his lands, as a result of which the princely domain decreased. The boyars, having received land holdings, often turned them into hereditary possessions. Thirdly, the bulk of the free community members were already dependent on the boyar patrimony, in connection with which the princely domain was in need of labor. The princes could attach to their domain only the lands of the communities that were not captured by the boyars. In Volyn, on the contrary, the princely domain united the vast majority of communal lands, and only then did local boyars begin to stand out and strengthen from it.

The most important role in the public life of the principality was played by the boyars - "muzhigalitsky". As already noted, a feature of the Galician land was that since ancient times, the boyar aristocracy was formed here, which owned significant land wealth, villages and cities and had a huge influence on the domestic and foreign policy of the state. The boyars were not homogeneous. It was divided into large, medium and small. The middle and petty boyars were in the service of the prince, often receiving lands from him, which they conditionally owned while serving the prince. The Grand Dukes distributed land to the boyars for their military service - "to the will of the gospodar" (to the will of the Grand Duke), "to the stomach" (until the death of the owner), "to the fatherland" (with the right to transfer land by inheritance).

The ruling group was joined by the top of the clergy, who also owned land and peasants. The clergy were exempt from paying taxes and had no obligations to the state.

Peasants (smerds), with the growth of large land ownership, fell under the rule of the feudal lord and lost their independence. The number of communal peasants decreased. The dependent peasants who inhabited the feudal lands were on the quitrent of that, they had obligations to the feudal state.

The urban population in the Galicia-Volyn principality was numerous, because there were no large centers such as Kyiv or Novgorod. The urban nobility was interested in strengthening the princely power.

The social composition of the inhabitants of cities became heterogeneous: differentiation here was also significant. The top of the cities were "men of the city" and "mystychi". The city elite was the backbone of the prince's power, showed a direct interest in strengthening his power, since they saw in this a guarantee of maintaining their privileges.

There were merchant associations - Greeks, Chudins, etc. Craftsmen also united in "streets", "rows", "hundreds", "brothers". Zgi corporate associations had their elders and their own treasury.

All of them were in the hands of the craft and merchant elite, to which the urban lower classes - apprentices, working people and other "smaller people" were subordinate.

The Galicia-Volyn land was cut off early from the great path from the Varangians to the Greeks, and early established economic and trade ties with European states. The elimination of this route had almost no effect on the economy of the Galicia-Volyn land. On the contrary, this situation has led to a rapid growth in the number of cities and the urban population.

The presence of this feature in the development of the Galicia-Volyn principality determined the important role of the urban population in the political life of the state. In cities, except for Ukrainian, German, Armenian, Jewish and other merchants permanently lived. As a rule, they lived in their community and were guided by the laws and orders established by the power of the princes in the cities.

Bibliography

1. Barkhatov of the domestic state and law. Publishing house: Rimis - M. - 2004;

2. Gorinov of Russia. Publishing house: Prospekt. - M. - 1995;

3., Shabelnikova of Russia. Publishing house: Prospect - M. - 2007;

5. History of the State and Law of Ukraine: Textbook. - K.: Knowledge, 20s.;

6. Rybakov of the USSR from ancient times to the end of the 18th century. - M.: Nauka, 1s.

In the 50-60s pp. 11th century Volhynia, Przemysl land and other lands of the Carpathian region were owned by Prince Rostislav Vladimirovich, the grandson of the son of Yaroslav the Wise Vsevolod. After him - Prince Izyaslav, then - his son Yaropolk, exercised custody of the three minor sons of Rostislav. Growing up, all three - the ruler Vasilko and Rurik - went to Kyiv, to the Grand Duke Vsevolod and began to demand the return of "father's possessions" - Volyn and the Carpathians. He did not give them Volyn, but returned the Carpathian region.

Therefore, Rurik "sat" in Przemysl, Vasilko - in Terebovl, Volodar - in Zvenigorod ^ These lands became separate principalities. After the death of Yaropolk, Volhynia received from the Kyiv Grand Duke David Igorevich into possession.

The Rostislavichi brothers stubbornly defended their patrimony from enemy encroachments from the Volyn prince David, who tried to seize their principalities, and then the Kyiv prince Svyatopolk, who took the throne after the death of Vsevolod. The troops of Svyatopolk Rostislavichi defeated, and subsequently the Hungarian army, which therefore came to the rescue.

The lands of the Rurikovichs were freed from claims from the Volyn and Kyiv princes. In search of allies, they established contact with Byzantium, began to strengthen their western borders, laying military settlements, fortifications, cities - Sanok, Prshevorsky, Lyubachev and others. of them - Rurik - died, and Vasilko was lured into a trap and blinded by David) European sources titled "Konig Ruthenorum", "Rex Ruthenorum" - the king of the Rusyns.

The lands of the Rurikovichs began to be called Galician Rus, since in the 11th century. in this region, the role of another large city, Galich, is increasing. The owner "held" Przemysl and Zvenigorod, that is, Nadsyanya, the Bug region and the upper Dniester region, and Vasilko - Galich and Terebovlya, that is, the middle Dniester region. They lived among themselves in harmony, which could not be said about most other princes of the then Kievan Rus.

In 1124, in the same year, both brothers, who had reigned for 40 years (since 1084), died. their balanced, coordinated and firm rule was of great importance not only for the Carpathian lands, but in general, as M. Grushevsky writes, "for Ukraine-Rus. Near ... inveterate wars, the independence of the Galician land was defended from Volhynia, from Poland and Hungary ... Galicia has emerged from the role of a Kiev clothespin, which Volyn has been for so long ... The existence of the Galician state and the Galician dynasty has been ensured ... the foundation has been laid for the greater significance of this distant Russian volost." After the death of the elder Rostislavichs, the Przemysl-Galician land was ruled by the son of the Lord - Volodymyrko. Since that time, Kievan political influences were finally forced out in the Carpathian lands.

Galician principality from the 11th century. gradually turns into one of the most powerful principalities of ancient Ukraine-Rus. As a result of colonization to the south, significant territories were annexed to it - up to the Danube. True, Volodymyrko, trying to strengthen the princely power, centralize administration, and increase the army, first came into conflict with his brother Rostislav and Vasilko's two sons, Yuri and Ivan. It came to an internecine war. But in the end he won. In 1141 Volodymyrko moved the capital of the united principality to Galich and it became known as the Galician principality. The main force on which he relied was a military wife and boyars. Developing the state, Volodymyrko tried to pursue a peaceful foreign policy - he almost did not attack Poland, did not fight with Hungary, and maintained friendly relations with the Kyiv princes. But when Vsevolod Olegovich sat on the Kiev throne, relations with Kiev in Vladimirovka deteriorated.

Vsevolod 1144 and 1146, trying to force Vladimirovka into obedience and recognition of the superiority of the Kyiv prince, organized two large campaigns against Galicia. Many princes took part in them - Volyn, Chernigov, Pereyaslav and others, even Polovtsy. Volodymyrko must recognize the "superiority" of Kyiv. Subsequently, he again pursued an independent policy, often interfering in the political struggle around the Kyiv throne, supporting one or another pretender (in 1146, Prince Vsevolod of Kiev died). At this time, relations between Vladimirovka and the Volyn prince Izyaslav, who, moreover (in 1151), occupied the throne of Kiev, sharply escalated. It came to the point of war. Volodimirko could defend the independence of the Galician principality, did not allow it to be turned into the patrimony of the Volyn or Kyiv princes. He finally united the disparate destinies of the Carpathian region, "built," as M. Grushevsky writes, "the strength and glory of Galicia ... and led Galicia to an important significance in the Russian political system, and even not only in it."

In 1153 the son of Vladimirka ascended the Galician throne (he died in 1153, having reigned for 29 years) Yaroslav. Nicknamed in "The Lay of Igor's Campaign" Osmomysl for his wise and far-sighted activity, he continued his father's policy of strengthening the Galician principality. Under him, it became strong, stable, centralized, neighbors were afraid to attack it, it developed intensively economically, and the population grew. Yaroslav, taking care of the economic development of the country, had significant funds, a large army. In 1154, in a great battle on the banks of the Seret, he met with the troops of the Kyiv-Volyn prince Izyaslav, who wanted to take part of the territory from Yaroslav. Although Yaroslav was defeated, Izyaslav did not rejoice at the victory for long, because he died the same year. But Yaroslav established good relations with the Poles, Hungarians, Prince Yuri Olegovich of Suzdal, helping them in the wars. When, in 1158, Prince Rostislav "sat" on the throne of Kiev, Yaroslav concluded an alliance with him, to whom he remained faithful to the end and more than once sent his regiments to Rostislav to help.

The authority, strength and power of Prince Yaroslav grew in domestic and foreign policy life. No wonder the author of "The Tale of Igor's Campaign" wrote about him: "Galician Osmomysl Yaroslav, you sit high on your gold-forged table, propped up the Ugrian mountains (that is, the Carpathians - auth.) With your iron regiments, blocking the way for the king, he closed the gates of the Danube ... Your coffins flow through the lands, you open the gates to Kyiv, you shoot from the father’s table salnativ behind the lands.

Yaroslav assigned the Dnistro-Danubian region to the Galician principality, colonized the lower reaches of the Dniester, Prut and Seret, received the Danube outlet to the Black Sea. Here, on the lower reaches of these rivers, the support centers of the Galician policy were built or fortified - Drestvin, Chern, Belgorod, Romanov Torg, Berlad, Small Galich (now Galati in Romania), Banya, Suceava, Kelya, etc. Here, according to archaeological sources and chronicles, one could see ships from Byzantium loaded with a variety of goods - wines, curtains, silks, glass, marble, and the like. Hungarian, German, Polish goods were delivered here. Galicia exported bread, honey, furs, salt, etc.

The strategic ally of the Galician principality at that time was Byzantium, with which a military alliance and a trade agreement were concluded. For a long time Yaroslav was visited by the cousin of the Byzantine emperor Emmanuel Andronicus Komnenos, who took part in the meetings of the boyar council, received several cities "for his maintenance". Yaroslav maintained allied relations with the German Empire. One of Yaroslav's daughters became the Hungarian queen by marrying King Stephen. True, Yaroslav was not happy in his personal life, sometimes he clashed with the boyars, whose positions in the Galician principality were always strong.

In 1187, Yaroslav, having caught a cold while hunting at the age of about 55-56, died. Vladimir sat on the Galician throne after a series of political conflicts between Yaroslav's sons Oleg and Vladimir (Yaroslav's testament - to transfer the "table" to Oleg was not fulfilled by the boyars). But his boyars were soon expelled, and he fled for help to the Hungarian king Bela III.

The Hungarian king went with an army to Galicia, occupied Galich. But when he saw a cool meeting with the Galicians of Vladimir, he changed his plans. He proclaimed himself king of Galicia, and appointed his son Andrei as his governor in Galicia (1189). To support him, Bela left a significant garrison.