Pier Harbor. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was not a surprise to US President Franklin Roosevelt. Chasing two birds with one stone

Pearl Harbor - bait for samurai

Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, began as usual at Pearl Harbor. The ships were slowly preparing to raise the flags. Brass bands lined up on the decks of majestic but outdated battleships. The radio broadcast jazz music. The base command was lounging in their beds. The pilots had just gone to bed after a wild Saturday drinking party. Predatory planes with large red circles on their wings fell on this idyllic picture like kites from a clear sky.

This sailor apparently knew that in 1937, the flagship of the US Asiatic Squadron, the heavy cruiser Augusta, visited Vladivostok with the destroyer Paul Jones on an official visit (after which Stalin shot almost the entire leadership of the Soviet Pacific Fleet for failing to cope with their reception ). But the fact that these were not the Russians paying a return visit, who at that time did not have any aircraft carriers anywhere near, became clear in the next moments.

Destruction?

Superbly trained Japanese pilots from six aircraft carriers, who secretly approached as part of an armada of 32 ships secretly assembled near the Kuril Islands at close range to Hawaii from the north, from where no one was expecting them, got down to business. Thanks to the surprise factor, everything went smoothly. The US participated in the beating of the Pacific Fleet 350 aircraft- bombers, dive bombers, torpedo bombers and fighters.

From the first wave, the Japanese lost only nine aircraft. Of the second - 20. But they damaged all eight battleships on site, four of which were sunk. However, all of them, except " Arizona", which later became a memorial, was restored and put into operation during the war. The Japanese also damaged or sank three cruisers, three destroyers, and a number of smaller ships.

Mostly at airfields, 188 American aircraft were destroyed. American losses were 2,403 killed and 1,178 wounded. Almost half of the dead - 1177 people - were sailors and officers " Arizona" In a capsized battleship " Oklahoma“Almost 400 corpses were found.

The attack by Japanese carrier aircraft on Pearl Harbor became the desired reason for the US leadership to enter World War II. Photo: Keith Tarrier / Shutterstock.com

To the Japanese losses, however, one should add the crew members of five small submarines, whose mission was a complete failure. The surviving and captured Japanese sailor then became the first prisoner of war, for Japan declared war on America simultaneously with the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Civilian casualties were insignificant and were largely the fault of their own anti-aircraft gunners, as only one Japanese bomb accidentally fell on the city. The huge mistake of the Japanese was that they, fearing a non-existent threat to their ships, refused a third strike on the base. And also that They did not bomb the power plant, docks, shipyards, ammunition depots, submarine parking lots, headquarters at all, and most importantly, they did not destroy, which could have been done simply, huge reserves of fuel.

On the ground they waited for the inevitable Japanese invasion. But it did not follow and was not even planned - Japan no longer had extra troops that had swallowed up the vast expanses of Asia . The Americans took revenge by lynching ethnic Japanese and Chinese legally residing in Hawaii. who were not distinguished - by their citizens. Even animals got it: a certain dog was suspected of “barking in code at a Japanese submarine.” Japanese Americans were then sent to concentration camps, and not just in Hawaii.

The Japanese lost a total of only 64 troops in this attack and joyfully celebrated their victory. They believed that America would not soon recover from this unexpected blow, and now nothing would stop the Japanese from taking what they wanted in Asia - right up to Australia. On the mast of the flagship aircraft carrier returning to its native waters " Akagi"The flag of the Imperial Navy flew proudly, under which on the battleship " Mikasa» admiral Togo sank and captured Russian ships at the Battle of Tsushima in 1905.

However, despite the enormous damage suffered by the Americans, the Japanese victory was incomplete, because the American aircraft carriers, the main striking force of the fleet, were not damaged at all - they were not in Pearl Harbor at the time of the attack. But the most important thing was something else. US public opinion was enraged by the incident. And if before the attack on Pearl Harbor most Americans were against their country's participation in the war, now they longed for it. Moreover, simultaneously with Pearl Harbor, the Japanese attacked from the air the American protectorate of the Philippines, where the US Asian Fleet was based, and destroyed the American bomber aircraft located there. They began landing troops in British Hong Kong and Malaya, targeting Singapore, the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia).

So the President of the United States Franklin Roosevelt, gradually preparing, together with his entourage, the Second World War, received the much-desired “day of shame” and demanded to declare war on Japan, in which the previously isolationist Congress strongly supported him. After Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, allies of Japan, declared war on the United States after Pearl Harbor, and Britain declared war on Japan, it became truly global.

US President Franklin Roosevelt seemed to many to be a naive, good-natured man, but he was more insidious and smarter than everyone else. Photo: Scherl/Globallookpress

This is not sloppiness, this is politics

However, it would be a big mistake to consider the US actions as irresponsible carelessness. Pearl Harbor, the loss of the Philippines, Guam and other territories in Asia by the Americans and especially their allies, the British and Dutch, the establishment of Japanese domination over them - all this was part of Roosevelt's “cunning plan”, which worked.

If you take a closer look at the US policy of those years, it becomes obvious that they themselves created this situation and provoked the Japanese. The latter, despite Japan's well-founded fear of war with the United States, turned out to be not at all difficult, as long as the strategy was “correct.” To do this, the Americans only had to abruptly stop connivance with Japanese aggression in China, curtail economic cooperation with Tokyo, freeze Japanese holdings in American banks, deprive Japan of metal supplies and especially oil, inciting the British and Dutch, who were dependent on the United States for everything, to do this, and, finally, expose their fleet (without the most valuable ships) in Hawaii and the “Flying Fortresses” in the Philippines to attack. Regarding the latter, before the Japanese attack, the American command spread rumors that in case of war they would bomb Tokyo, refuel in Vladivostok, bomb again and return to the Philippines...

Trap for the Japanese

The Japanese didn't really want a war with the US because of the difference in weight classes. They understood perfectly well how little chance they would have of getting out of this mess. After all, a revolution like the First Russian, which did not allow the tsarist army, which had learned to conduct modern warfare, to crush the Japanese in Manchuria, would not have happened in America. However, as a result of the trade blockade, there was only enough fuel for their ships, planes and tanks for a few months. Therefore, the Japanese, with their samurai code of honor, had no choice but to fight. Especially when the United States demanded the withdrawal of Japanese troops from China, a significant part of which they had already captured, and even - the Japanese got the impression due to the deliberately unclear American wording - to leave Manchuria.

Imperial Japan had a strong navy and army, but could not last long in the war with the United States due to America's enormous economic superiority. Photo: Scherl/Globallookpress

All this meant that Japan must abandon its policies of recent decades, admit that all the sacrifices and expenses were in vain, and voluntarily turn into a country dependent on the United States. In order to give the Japanese a chance to avoid this, Roosevelt ordered in 1940 to keep the American Pacific Fleet in Hawaii in winter, where there were no necessary conditions for this, but where the Japanese could actually reach it.

They knew everything

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7 was not at all unexpected by Washington. The Americans had cracked the Japanese codes and knew what the Japanese were going to do, where they would strike if the negotiations reached a dead end, where the US President’s entourage deliberately led them. At the same time, everything was done to ensure that the American command in Hawaii and the Philippines remained in the dark, so that the losses suffered would become a reason to declare war on Japan. Roosevelt, who attributed the “shame” of December 7 to his military, could not attack Japan without such a reason.

Thus, American naval intelligence has been reading Japanese diplomatic correspondence since 1940 (the Japanese used an encryption system similar to the German one, which the British opened). And they often did this even more quickly than at the Japanese Embassy in Washington. Therefore, they had the opportunity to warn their fleet and base at Pearl Harbor of the imminent attack. This was done after deliberate delays, when Japanese bombs were already exploding there. Because for “political reasons,” Roosevelt needed the Japanese to go first.

The Japanese coped with everything

Japan was given a special mission by the American leadership. The attempt to create a “Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere”, the dismantling of the old European colonial empires in Asia, the discrediting of the cult of the “white man” on which they were based, the brutal exploitation of the natives by the Japanese themselves for their own selfish interests - all this was part of it.

This was supposed to create fertile ground for a new type of empire to take root in Asia after the war, an American one - with formally free countries, without pompous colonial officials in pith helmets, but with all-powerful US embassies and military bases, American financial and economic dictatorship. And that means political.

It was not difficult for the United States to recapture one Pacific island after another from the Japanese, since they had stretched their forces too thin. Photo: Scherl/Globallookpress

To achieve this goal, the Japanese had to start with victories, occupy as much territory as possible, lose their superbly trained, but insufficient number of pilots in these battles, and embitter the local population against themselves, instilling in them the idea of independence. And then, when in a few years the United States, the “arsenal of democracy,” creates enormous military power using the wide flow of money and gold flowing to them from all over the world, they will be defeated. And in the air, and at sea, and on land. That's exactly what happened. And it couldn't help but happen. All this was calculated in advance.

Let's sum it up

Already in 1942, the Americans began to recapture the captured Pacific islands from the Japanese who had reached Australia. The war ended when, in 1945, the invasion of Japan by a huge American army became the order of the day. She was brought to submission by the defeat of the Kwantung Army by Russia in Manchuria and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and then occupied by the Americans.

In the former European colonies in Asia, the colonial masters who returned after the war were unable to restore the old order. The Malays, Singaporeans, Indonesians, Burmese and others saw during the years of Japanese occupation the weakness of the colonial power, the humiliation of their former colonial masters and did not want to return to the past, pretending that nothing had happened. The Americans helped them in this, who were prevented from expanding by the old colonial empires of the Europeans.

This is the true meaning of Pearl Harbor, as one of the most ambitious and successful American provocations in the name of establishing world domination. September 11, 2001 will be called the “New Pearl Harbor” in the United States. In the entire Second World War after Pearl Harbor, the United States lost 418 thousand people killed (one third less than the USSR only in the territory of modern Poland), and became the richest and most powerful country in the world, which is still “working hard” for the United States. For this, in fact, everything was started.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki are also consequences of Pearl Harbor. Photo: Scherl/Globallookpress

Unfortunately, the Americans usually succeeded in provocations. Here are just a few of them. "Boston Tea Party" which led to the creation of the United States. Explosion of the armored cruiser Maine in Havana Bay, providing the United States with its own colonial empire. Destruction of the Lusitania, which became the reason for entering the First World War. Staged incidents in the Gulf of Tonkin which allowed the United States to get involved in the Vietnam War. Destruction of an Iranian civilian Airbus over the Persian Gulf, which forced Tehran to end the war with Iraq when Iran began to win. Attributed to the regime of Muammar Gaddafi terrorist attack on board an American Boeing in the same year over Scotland, which became the prologue to the destruction of Libya...

Just like Pearl Harbor and September 11, all of these are confirmed provocations, and not the fruit of a sick fantasy. The USA is a provocation. Everyone should learn this maxim well and be vigilant.

The main aggressor. All US wars - 1903-2011

On the attitude in the USA towards the Japanese at the beginning of the Second World War and towards the indigenous Indians

How Hawaii became the 51st US state

More details and a variety of information about events taking place in Russia, Ukraine and other countries of our beautiful planet can be obtained at Internet Conferences, constantly held on the website “Keys of Knowledge”. All Conferences are open and completely free. We invite everyone who wakes up and is interested...

30. ATTACK ON PEARL HARBOR

I fired him from office because he showed no respect for the authority of the President. Just because. I didn’t kick him out because he’s a stupid son of a bitch, although that’s true, but among the generals it’s not considered a vice at all. Otherwise, half, if not three-quarters of our generals would have ended up in prison.

President Tarry Truman on the removal of General MacArthur from command of American troops in Korea

The date of the attack on Pearl Harbor was not chosen by chance. In a report to the Emperor, Admiral Nagano (Chief of the General Staff of the Navy) explained: “We will gain additional advantages by starting operations on Sunday, the American rest day, when a relatively large number of warships are concentrated in the port of Pearl Harbor.”

Nagano also told the emperor: “We believe that the most favorable time will be approximately the twentieth day of the lunar cycle, when the moon shines in the sky from midnight to sunrise.” After consulting the lunar calendar, Japanese military leaders found that Sunday, December 7, 1941, fell on the nineteenth day of the lunar cycle, and decided that this was exactly what was needed.

An unprecedentedly powerful carrier strike force of six ships under the command of Admiral Nagumo was accompanied by two high-speed battleships, three cruisers, nine destroyers, three submarines and eight tankers, which were to replenish fuel reserves on warships en route. Braving winter storms, the Japanese chose a northern route away from the main shipping routes, avoiding areas they knew were being patrolled by air. The weather, considering the time of year and latitude, was very favorable. Transferring fuel - a task that would have been very difficult in a storm with strong seas - was carried out in calm weather under the cover of fog. Even in the final stages of the operation, the weather favored the Japanese. When the first wave of planes approached Pearl Harbor, the clouds parted at the most favorable moment, so that everyone became convinced that the operation was guaranteed by the grace of the gods.

The Japanese expected their ships to be discovered and attacked. Yamamoto warned his men that they would likely have to fight their way back to their original positions. They were amazed to find that the Americans were completely unprepared for the attack and offered virtually no resistance.

Unlike the Western powers, Japan recognized the importance of intelligence. The spies provided the Japanese command with detailed diagrams of Pearl Harbor's piers and schedules for the arrival and departure of American battleships. Of particular importance when planning the operation was the fact that on weekends the American fleet, as a rule, was in the harbor. However, nothing contributed more to the success of the Japanese raid than the lack of long-range aerial reconnaissance by the Americans. During the investigation into the causes of the disaster, the excuse was put forward that there were only 36 combat-ready aircraft available, thus conducting a full-fledged all-round reconnaissance was impossible. First, the Navy could have asked the Army for aircraft, but interdepartmental rivalries prevented this. Secondly, in any case, it was generally believed that the attack, if it was to take place at all, was to be expected from the north, so at least the available reconnaissance aircraft could be concentrated in this sector.

On December 3, the codebreakers read a message sent from Tokyo to the Japanese Embassy in Washington, ordering the codebreakers to destroy all encryptors and encryption tables with the exception of one machine and one set. The Assistant Secretary of State, having reviewed this document, said that "the chances of avoiding war have decreased from one in a thousand to one in a million." President Roosevelt was of the same opinion. “When do you think this will start?” - he asked the assistant for naval affairs, who showed him this interception. But Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, saw no signs of impending war. The fleet continued to live according to peacetime laws. Even despite the successful operation at Taranto, American admirals continued to stubbornly cling to the assumption that a torpedo dropped from an aircraft required depths of at least 100 feet to be effective. Kimmel banned the installation of anti-torpedo nets in the area of the piers, saying that it would interfere with the movement of ships.

It seems that the generals and admirals agreed on one thing: there should be no concessions to the looming threat of war. On the day before the Japanese attack, Rear Admiral Leary, who was inspecting the light cruiser Phoenix, specially put on white gloves to check for dust. Only after the end of the inspection the team was released ashore. However, in practical terms, the ship turned out to be completely unprepared for battle: when the attack began the next morning, it was necessary to cut the locks off the doors of the cruise chamber and tear down the awnings over the anti-aircraft guns in order to clear the field of activity for them. In addition, it turned out that many anti-aircraft shell fuses were unreliable: unexploded shells “rained down onto the shore.”

Officers who demanded that their subordinates prepare for war instead of a peaceful routine were extremely unpopular. The senior officer (first deputy commander) of the cruiser Indianapolis, who kept the ship in “combat readiness number two,” that is, with its guns uncovered, ready for battle, and ammunition prepared, listened to complaints from his wife: “The wives of all the officers of the cruiser ask me: “ What is Indianapolis doing? Are you going to fight alone? Their husbands are hardly at home, and they are very upset about it.” After the attack, when the senior officer’s fears were confirmed, the captain said: “Another week and the crew would have thrown us overboard.”

Long ago, back in 1921, Air Corps General "Billy" Mitchell carried out a demonstration bombing of old battleships, showing that aircraft were capable of sinking large warships. This did not please either the large steel corporations that built these mighty ships, which formed the basis of the fleets of all the world's leading powers, or the battleship-loving admirals who stood at the head of these fleets. The sinking of the leviathans was explained by the fact that Mitchell had violated the restrictions placed on him by those who were determined to ensure the failure of his demonstration at any cost. Despite some lessons from the first year of the war in Europe, the striking power of bomber aircraft was soon forgotten. Even Yamamoto had to fight back in Japan with skeptics who doubted the possibility of destroying large warships with air strikes.

Conspiracy theory

The chaos and confusion that led to the disaster gave rise to hundreds of far-fetched theories. Through his domestic policies, Roosevelt made fierce enemies who were willing to believe the worst about him. There are plenty of books and articles about what happened, sometimes from the pens of high-ranking American officials. Many baselessly claim that President Roosevelt deliberately provoked Japan by contributing to the disaster at Pearl Harbor. To prove their point, they cite misinterpreted and distorted reports of US-Japanese negotiations, claiming that the President had an inkling of the impending attack.

The most comprehensive work on what happened is a 3,500-page work by Gordon W. Prange, the result of 37 years of research. In it, the author rightly rejects all such fictions. How can one accept that Roosevelt was willing to sacrifice the Pacific Fleet - the most important weapon of the impending armed conflict - in order to justify a declaration of war?

The most absurd theories are those accusing Churchill of plotting to drag the United States into the war. The British Prime Minister allegedly knew about the impending attack on Pearl Harbor, but did nothing to prevent it. One recent book claims that the British read messages sent by Admiral Nagumo's strike force, but Churchill kept the results of the interceptions secret from the United States. In fact, the Americans could read Japanese codes themselves, but Nagumo was so determined to maintain radio silence that the operator keys were physically removed from all transmitters.

No one knew better than Winston Churchill how vulnerable the British colonial possessions were. For two years, Britain drained troops stationed in Southeast Asia to continue the fight against the German war machine. She survived 1941 solely thanks to the ongoing support of Roosevelt and the help of the American fleet in the Atlantic. If there was one thing Churchill wanted to avoid, the first on that list was the Japanese invasion of Malaya and Burma (the inevitable consequence of which would be the diversion of United States military forces to the Pacific theater).

But the Pearl Harbor disaster was marked by a huge number of mistakes and short-sighted stupidity. Prange's work rejects the idea of placing all the blame for what happened on any specific people.

“A huge stain of shame lies on all of America, from the President to the Fourteenth Naval District and the Department of Hawaii. There are no Pearl Harbor scapegoats.”

On the morning of the attack, Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, the pilot chosen by Genda to lead the strike force, woke up at 5 o'clock. At breakfast they told him: “Honolulu is sleeping.” When asked how this was known, the officer on duty replied that they were broadcasting calm music on the radio.

Having carried out the last refueling of the ships, Nagumo conveyed a message from Yamamoto to the personnel of the strike force. Following Admiral Togo, who based his 1905 address to the navy on Nelson's famous order before the Battle of Trafalgar, Yamamoto declared: “The rise and fall of the empire depends on the outcome of this battle. Let everyone do their duty."

The carrier armada took up its initial positions 235 miles north of the target at 6 a.m. on December 7, 1941. Vice Admiral Nagumo was on board the aircraft carrier Akagi. The wind fluttered the historical “Z” flag raised on the mast, which was on Togo’s flagship during the Battle of Tsushima in 1905, which ended in a crushing defeat for the Russian fleet.

Two of Nagumo's aircraft carriers, Shokaku and Zuikaku, were completely new, and their pilots had no combat experience. They had to provide support for the actions of the main forces. The first to take off were the Aiti E13 A (“Jake”) flying boats. They had to make sure that there were no enemy ships in the path of the strike armada. Then all aircraft carriers turned to the east, against the wind, and increased speed to 24 knots. Their decks rose upward at an angle of 10 degrees. Fuchida subsequently said that under normal conditions, “not a single plane would have been allowed to take off... Every plane that took off was greeted with loud shouts.” The flagship, "Kara", "Soryu" and "Hiryu" lifted the first wave into the air. Most of the pilots refused to take parachutes, saying that if the plane was seriously damaged, they would “turn it into a bomb” - at the cost of their lives they would direct it at the enemy.

The first wave consisted of 183 vehicles. First, 43 A6M2 Zero fighters took off from the decks of aircraft carriers, quickly gaining altitude to cover the takeoff of the remaining aircraft from the air. Then 51 Aichi DZA4 (Val) dive bombers took off, then 49 Nakajima B5N2 (Kate) bombers and, finally, another 40 of the same machines equipped with the main weapon - torpedoes. Two planes never made it to Pearl Harbor: one Keith suffered an engine failure, and one Zero crashed on takeoff. All aircraft (181) took off in 15 minutes; During the exercise, this could not be accomplished in less than 20 minutes.

Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

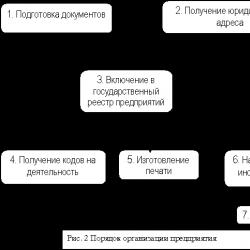

First raid. Starts at 7.40 am, duration 30 minutes

40 torpedo bombers

49 bombers

51 dive bombers

43 fighters

9 aircraft shot down

Second raid. Starts at 8.50 am, duration 65 minutes

54 bombers

78 dive bombers

35 fighters

20 aircraft shot down

The numbers on the diagram indicate (from northwest to southeast in each group of ships):

1. Minelayers “Ramsey”, “Gamble”, “Montgomery”

2. Minelayers “Trever”, “Breeze”, “Zane”, “Perry”, “Wasmouth”

3. Destroyers "Monaghan", "Farragut", "Dale", "Aylwin"

4. Destroyers "Henley", "Patterson", "Ralph Talbot"

5. Destroyers Selfridge, Case, Tucker, Reid, Coningham; messenger ship "Whitney"

6. Destroyers “Phelps”, “Maedonow”, “Worden”, “Dewey”, “Hull”; messenger ship "Dobbin"

7. Submarines “Narwhal”, “Dolphin”, “Toytog”; aircraft "Thornton", "Halbert"

8. Destroyers Jarvis and Mugford (between Argonne and Sacramento)

9. Destroyer "Cummings"; minelayers “Preble”, “Tracy”, “Pruitt”, “Sicard”; destroyer "Schley"; minesweeper "Greb"

10. Minesweepers “Bobolink”, “Vaireo”, “Terki”, “Rail”, “Tern”

The remaining ships, not shown in the diagram, were anchored in Western Bay. Also, the diagram does not show boats, tugs and auxiliary vessels.

The plan provided that if the effect of complete surprise was achieved, the Keiths would be the first to strike, but if the enemy offered serious resistance, the attack would be led by dive bombers. The signal should have been given just before approaching the target by Commander Fuchida.

Flying over thick clouds, Fuchida himself heard the “calm music” of American radio stations and used the signal from the commercial radio station KGMB in Honolulu to reach the target. The station did not normally broadcast this early in the morning, but the Air Force paid it to broadcast music throughout the night so that B-17 bombers heading to the Hawaiian Islands could tune their direction finders to the signal. Some warned that this was very bad for reasons of secrecy, since everyone knew when planes from the mainland flew to Hawaii.

At half past six in the morning, a naval aviation PBI flying boat discovered a small Japanese submarine at the entrance to the port and, dropping depth charges, sank it. At 6.45 in the morning, the operator of a land radar station saw a dot on the screen - it was one of the Japanese flying boats sent for reconnaissance. This long-range radar detection station for air targets SCR-270 in the town of Opa-na looked through exactly the sector of the ocean where the Japanese fleet was located. The radar operators did not attach much importance to the incident, but after a few minutes the screen lit up with numerous dots indicating the approach of a large group of aircraft.

On weekdays, radar operators worked around the clock, but on weekends, the shift ended at seven o'clock in the morning, after which the radars were turned off. On that fateful day, the car taking the soldiers to breakfast was delayed. Operator Joseph Lockard's testimony:

“At 7.02 Elliott, crouching in front of the screen, suddenly exclaimed: “What is this?” “Let me take a look,” I said. There was a huge glowing spot on the screen; I've never seen anything like this!

When we first discovered them, they were, I think, 155 miles away. Now I’m no longer sure of these figures, but I remember for sure that the planes were approaching us strictly from the north... At first we decided that there was some kind of equipment failure, so we ran a series of tests... All devices were functioning properly, so we began to determine the coordinates of the target. Then someone suggested that we contact our superiors by phone. [The telephone operator, after a long search, connected the operators to Lieutenant Kermit Tyler.] We were told: “Everything is in order. B-17s are due to arrive from the States; True, they have gone very far off course.”

We tracked the target for a while, then called headquarters again. Lieutenant Tyler told us not to worry.

We were flying the planes, but when they were about 20 miles from the island, they disappeared from the radar screen due to interference caused by the signal reflected from the mountain ridge."

At 7:40 a.m., Fuchida, flying along the coast of Oahu, fired a flare. This was the signal for the bombers to turn in to attack Haleiwa and Wheeler airfields and Schofield Barracks. However, the escort fighters did not see this missile, so Fuchida was forced to launch a second one. Two missiles were a signal that it was not possible to take the defense by surprise. Therefore, the planes began to act according to a backup plan. Instead of a successive strike first by torpedo bombers and then by bombers, the formation of Japanese aircraft collapsed and a free hunt began.

A 550-pound bomb hit the barracks at Hickham airfield and exploded in the mess hall, killing soldiers eating breakfast there. Japanese pilots, unopposed, flew at very low altitudes. Some planes with fixed landing gear cut telegraph wires with them. American soldiers on the ground retained for the rest of their lives nightmarish memories of pilots looking at them from the cockpits of low-level aircraft. The Japanese attack on Hickham airfield coincided with the approach of B-17 bombers, some of which were shot down during landing. The rest, turning towards Bellows airfield, ran into Japanese fighters. American bombers were unable to repel their attacks, since all machine guns had been removed and mothballed. The American planes stationed at the airfields made excellent targets. By order of the commander of the ground forces, they stood wing to wing - as he explained, to prevent sabotage.

Looking around the inner roadstead, Fuchida saw battleships crowding around Ford Island. At 7.49 he sent a conditional message notifying the fleet of the start of the attack. All history textbooks contain this war cry: “Torah! Torah! Torah!" (“Tiger! Tiger! Tiger!”).

In fact, the radios installed on Japanese aircraft were very primitive. Messages were transmitted not by radiotelephone, but using Morse code.

Lieutenant Commander Tadakazu Yoshioka, who was on the Akagi, was in charge of communications, and he chose two different, easily recognizable signals for the message. Fuchida was to announce the start of the attack by transmitting a dot-dot-dash-dot-dot (“to”) signal, followed by a dot-dot-dot (“ra” signal if the enemy was surprised) ). For greater reliability, the signals should have been transmitted three times. Yoshioka subsequently admitted that he had no intention of turning the two syllables of tora into the word “tora,” Japanese for “tiger.” Be that as it may, the radio operator of Fuchida’s plane transmitted the agreed signal.

Pearl Harbor, located on the south coast of Oahu, is an intricate, winding harbor ideal for a naval base. In the middle of the open water is Ford Island, around which there are numerous piers, including the “battleship row”, where large ships were moored two at a time.

At 8 o'clock in the morning, flags were raised on the battleships peacefully moored at the berths. On the Nevada, when the first Japanese planes rushed towards it, the orchestra played the American anthem. The belief “this is simply impossible here” was so deeply rooted in everyone’s minds that most American sailors refused to believe their own ears and eyes. Many have only heard the music of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The Arizona helmsman says:

“But then bombs started falling, deafening explosions were heard and - boom! - one of them hit the bow of our battleship. I said to someone standing nearby: “It seems that someone will get the first number. They hit the ship!” I still continued to believe that these were exercises, but too close to a combat situation, since the battleship was damaged.”

Another member of the Arizona's crew, Don Stratton, a sailor first class, shared his impressions fifty years after the incident in a special issue of Life magazine:

“We received a hit on the starboard side, and immediately the ammunition and aviation kerosene caught fire. There was a terrible explosion, and a fireball shot up 400 feet into the air. Of the 50 or 60 people who were at the post with me, I think only six survived. 60 percent of my skin was burned. The Vestal, an auxiliary ship moored nearby, threw a line at us and we walked over it on our hands, 45 feet above the surface of the water.”

To penetrate the thick armored decks of battleships, the Japanese used 16-inch shells converted into 1,760-pound cumulative bombs. One such bomb pierced the deck of the Arizona in the area of the main caliber turret number two and hit the cruise chamber, which contained over a million pounds of explosives. A terrible explosion followed, throwing the huge ship 20 feet above the surface of the water, after which the battleship broke in two and quickly sank at a depth of 40 feet.

Admiral Kimmel ran out onto the lawn of his house, pulling on his white jacket as he walked. From there the “battleship row” was clearly visible. His neighbor (the wife of Captain Earl, the chief of staff of the fleet) saw that Kimmel's face was as white as his jacket. Kimmel recalled: “The sky was full of enemy planes.” Before his eyes, the Arizona jumped above the water, crashed down and disappeared from sight.

It seems they hit “Oklahoma,” Mrs. Earl noted.

Yes, I see,” Kimmel responded.

Provided that the aircraft descended to a very low altitude, the wooden horizontal rudders installed on Japanese torpedoes ensured that the torpedo dived only to a depth of 35 feet, and then, without getting stuck in the bottom mud, it floated to combat depth and rushed to the target. (In May 1991, during the clearing of the bottom, one such torpedo was raised to the surface. Currently, its tail section with improved horizontal rudders is on display at the Arizona Memorial.)

One sailor on the upper deck of the West Virginia calmly watched the dive bombers approaching their target. He was so sure that this was a training exercise that he moved to the other side to look at the torpedoes dropped into the water.

“We saw three planes flying very low above the surface of the water drop torpedoes. My friend, patting me on the shoulder, said: “When they hit the ship, we will only hear a soft knock.” And suddenly there was a hellish roar, and a wall of water, like a wave in a force twelve storm, rolled across the deck and washed us to the opposite side. Our ship was hit by six more torpedoes. The Tennessee was hit by a bomb. Our captain's insides were torn out by a huge fragment. We carried him down, and he gave orders until his death.”

Oklahoma was hit by seven torpedoes. She was struck first by Second Lieutenant Jin'ichi Goto, who claimed that he was flying approximately 60 feet above the surface of the water. "The anti-aircraft fire was very heavy," Goto recalled on the fiftieth anniversary of the attack. Seeing a column of water raised by the explosion, he exclaimed: “Atarimasita!” - “I got it!”

The fuel oil leaking from the California's tanks caught fire, and soon the entire port was filled with black smoke. "Oklahoma" lay on board and sank. One of her crew, George DeLong, was in the aft helm compartment, located third floor below deck level, a crypt-like space that would normally be avoided by claustrophobics. Delong took his place at the alarm signal, then the command was heard: “Close the watertight bulkheads!” - and its compartment was tightly sealed from the outside. DeLong and seven of his comrades remained inside.

Almost immediately after this, torpedo explosions thundered, and the huge battleship began to lie on its side. “All the cutlery and other items fell off the table onto the floor.” The lights went out and the ship continued to capsize. “I realized that now my head is where my legs were just recently. When the ship finally stopped spinning and we were able to let go of what we were holding on to, we realized that it had turned upside down.”

Water began to seep into the ventilation system openings. The sailors, using the means at hand, tried to plug up all the cracks as tightly as possible, but the water continued to rise. When she had already risen to her chest, the sailors began to knock on the hull with a wrench, giving an SOS signal using Morse code. After some time, a hole was made in the sheathing using pneumatic drills, and DeLong was saved. He was 19 years old at the time, and he was destined to remain alive and tell about what happened to him fifty years later. Most of his comrades died.

By 0825, six battleships had been sunk, sinking, or seriously damaged. The first air raid lasted about thirty minutes. The second wave, consisting of 167 aircraft, arrived at 8.40. Bombers struck first, then dive bombers, and fighters came last. By this time, the number of American anti-aircraft guns entering the battle had increased significantly, and they managed to shoot down three fighters.

One young midshipman in the Naval Reserve, who was delivering documents to the headquarters of the Pacific Fleet that morning, remembers the incident as if it were just yesterday:

“On that fateful morning, I had to go into the office of Admiral Husband Kimmel several times. He was a lean, middle-aged man, very hot-tempered. He looked nothing like the actors who played him in the films. Far from calm and collected, the real Admiral Kimmel cursed and screamed every time he read the terrible reports of sinking and exploding battleships, destroyed aircraft on airfields and bombed barracks that I delivered to him. He became flushed and excited. I don’t blame him for taking out all his anger on me, since I only brought bad news that day.”

Kimmel had every reason to be angry. He received this position by going over the heads of other naval commanders, after his predecessor as commander of the Pacific Fleet strongly opposed the transfer of the main base from San Diego to Pearl Harbor. Kimmel now knew that all the anger would be directed at him—and the commander of the ground forces stationed in Hawaii—and he would undoubtedly be removed from office.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor occurred at a time when there were no American aircraft carriers at the base. The Sara Toga was sent to California for repairs and maintenance. The Enterprise, which was transporting aircraft to the Marine Corps base on Wake Atoll, was supposed to anchor thirty minutes before the attack began, but was delayed while replenishing fuel supplies. SBD-2 aircraft taken off from an aircraft carrier. The Dauntless, bound for Ford Island, encountered the first wave of Japanese bombers. The naval pilots thought that they were facing ground aircraft from the U.A. Field airfield, a Marine Corps Air Force base, but then their planes came under fire from anti-aircraft guns and were attacked by Japanese fighters. However, even now the American pilots could not believe that the war had begun. Midshipman Manuel Gonzalez shouted on the radio: “Please don’t shoot! This is board six-b-three. This is an American plane!”, but it was shot down by a Zero. Of the sixteen Dauntless, five vehicles were hit. Some were shot down by Japanese fighters, the rest by American anti-aircraft gunners. The Enterprise, turning to the west, headed away from the island and returned only after dark. But even by that time the sky had not yet become safe. A naval hospital orderly recalls:

“It was already getting dark when four low-flying planes appeared over the strait, heading for the piers. Almost all naval anti-aircraft guns opened fire on them. The saddest thing is that it turned out that these were American planes from the aircraft carrier Enterprise. Three planes were shot down, and the pilot of the fourth was taken to our hospital with numerous injuries. In total, the hospital could accommodate about 300 patients. By midnight we already had 960 wounded. And on the street, like stacks of firewood, 313 dead were stacked.”

It was vital for the Japanese to destroy all American aircraft so that none of them could track the Japanese bombers returning to the aircraft carriers and determine the location of the fleet. Airfields were therefore the primary target, and the first raid used more aircraft to attack American airfields than to attack warships. At 9 am a second wave of Japanese planes appeared. Each pilot had his own specific mission, with the main emphasis being on bombing airfields.

The last Japanese planes turned back at approximately 9.45. On the ground, 188 American aircraft were destroyed and 159 were damaged. Fuchida lingered over the target for a long time, studying the consequences of the strike. On the way back, he found two Zeros that had gone off course and escorted them home. After the attack began, Japanese aircraft carriers moved an additional 40 miles closer to shore to assist aircraft that were running low on fuel.

Having landed, Fuchida saw refueled and armed aircraft standing on the flight deck, ready for a new flight. While the carrier force remained in place to allow damaged aircraft to find it, an exchange of views took place on the Akagi's bridge. Fuchida was not the only one pushing for a third strike. The pilots of the squadrons based on Hiryu and Soryu were also eager to return. The captain of the Kaga personally asked for permission to strike targets that, according to his pilots, remained untouched. On the other hand, the technicians could not help but notice how much more damage the Japanese planes received during the last raid. American anti-aircraft gunners woke up, their guns were ready for battle. They had to meet the next blow fully armed.

In addition, there was a possibility that the strike force would be suddenly attacked by American aircraft carriers. It seems that this consideration alone was enough to make the decision to withdraw, although in reality everything was just the opposite: the powerful formation posed a mortal danger to the surviving American ships. The overly cautious Nagumo decided that what had already been done was enough. The carrier force turned back, maintaining radio silence. Requests from two stray Japanese bombers to signal direction finders went unanswered.

The Japanese pilots were not able to act with complete impunity. The 47th Interceptor Squadron, 5th Fighter Group, having performed unsatisfactorily in target practice, was exiled to Haleiwa Airfield on the northwest coast of Oahu for additional training. Two of its pilots managed to get their P-40B fighters into the air. These pilots danced all night and then went to the barracks, where they played poker until the morning. One nice story claimed that they jumped into the cockpits of their planes in tuxedos, but, alas, recent research shows that the pilots still managed to reach their beds and were asleep when the Japanese attack began. Without receiving permission to take off and without even passing pre-flight checks, the two lieutenants took their planes into the air and headed towards the Yua airfield, where there was the highest activity of enemy aircraft. Kenneth Taylor and George Welch shot down four Keiths between them. Welch then added "Val" and "Zero" to his victories. No one can say for sure which of the two won the first American Air Force victory of the war. According to Taylor: “George and I agreed not to tell anyone who would win the first victory, so that the survivor could take credit for it.” Both pilots survived and both received awards, but Welch's nomination for the Medal of Honor was rejected because he took off without orders!

The pilot of one of the Dauntless from the Enterprise, shot down over Pearl Harbor, had the opportunity to see the scene of events while descending by parachute. He saw that the Nevada had lifted anchor and began to slowly emerge from the “battleship row.” “All her anti-aircraft guns were firing,” he recalls. Even after another heavy bomb hit the deck, exploding with a “deafening, ear-splitting roar,” the gunners did not abandon their posts. “Several people were killed, many were wounded; but only one gun stopped firing.”

The American artillerymen fought desperately. First Lieutenant Zenji Abe, one of the Japanese pilots, recalls:

“When I appeared over Kaneohe Bay, the whole sky above the clouds was covered in explosions of anti-aircraft shells. I was surprised at how dense the barrage was. The American anti-aircraft gunners reacted so quickly. A shiver ran down my spine. The entire Pearl Harbor was covered in black smoke, through which tongues of flame broke through. I concentrated, trying to find my target. Finally I decided on a large ship. As it turned out later, it was “Arizona”.

The Army radar station at Opana was turned on again at 9 a.m., just in time for operators to spot Japanese planes returning to their carriers. But no one thought to ask them what they had found, so when at 11:40 a.m. six B-17 bombers took off in search of the Japanese fleet, they headed south and, of course, found nothing.

Now, with only twenty-five Catalina flying boats and a dozen B-17s remaining unharmed, command discovered that aerial reconnaissance still feasible. Soon the flying boats were already combing the sea within a radius of 700 miles - in all directions. The Flying Fortress bombers were put on thirty-minute alert.

Meanwhile, there was a desperate struggle to save the sailors trapped in huge steel hulls. 16-year-old apprentice shipyard worker John Garcia said:

“The next morning I took my instrument and set off for the West Virginia. The battleship turned upside down. We found survivors inside... For about a month we cut off the West Virginia's superstructure to turn it back over. By the eighteenth day we managed to free approximately three hundred surviving sailors."

When asked how these people managed to stay alive, Garcia replied: “I don’t know. We were so busy that we didn't have time to ask."

The restoration of sunken battleships was a magnificent demonstration of engineering. Even before the end of the war, all of them, with the exception of three, were completely repaired and put into operation. But the United States government, with acetylene torches already tearing into the steel of the crippled battleships, continued to believe that the American public was not yet ready to learn the whole truth about what happened at Pearl Harbor.

Secretary of the Navy Colonel Frank Knox returned to New York from Hawaii with encouraging news. At a press conference, he told reporters that one battleship, the Arizona, was lost, and the other, the Oklahoma, lay on its side but could be restored. Knox assured them that the balance of power in the Pacific had not changed significantly and “the entire United States Pacific Fleet - its aircraft carriers, heavy cruisers, light cruisers, destroyers and submarines - undamaged by the raid, is at sea and looking for a meeting with the enemy."

Noticing the absence of battleships from the list of ships “seeking a meeting with the enemy,” one journalist asked whether the battleships had put to sea. Knox replied that they had left. The Times of London, reprinting Knox's statement, noted that: “The full description of the losses given by the Secretary of the Navy, on the whole, made an encouraging impression. Americans are no more afraid of the truth than the British... Only dictators are forced to keep their people in the dark.”

During this attack, unprecedented luck accompanied the Japanese in all respects. Until then, very few people realized that aircraft carriers were the decisive offensive weapons of fleets. But fate played a cruel joke on the Japanese. The attack on Pearl Harbor proved the importance of aircraft carriers, but the operation as a whole ended in complete failure. American aircraft carriers were not destroyed at the very beginning of this war, in which carrier fleets were destined to play a stellar role. The ancient battleships that sank at shallow depths in the harbor were of no value. Moreover, their loss forced American admirals to recognize the dominant role of high-speed aircraft carriers.

And, fortunately for the Allies, American aircraft carriers were excellent ships; the last of those that entered service were superior to all those available at that time in the world. The two sister ships, Yorktown and Enterprise, were built from selected materials, with attention to the smallest details. According to one expert, these were the “Cadillacs” of aircraft carriers... Fast, reaching speeds of up to 33 knots, maneuverable, stable, capable of carrying large aviation units on board, the Yorktown class aircraft carriers were equipped with reliable waterproof bulkheads, and also had good flight armor deck and engine room."

At Pearl Harbor, 4.5 million tons of fuel remained in oil storage facilities that were not damaged in the attack. Dry docks, warehouses with all kinds of spare parts and workshops with precision equipment were also untouched. And it was not luck: all these objects were not on the Japanese target list. Also, the submarine base at Quarry Point was not hit.

Submarines

In 1930, the strategists of the Imperial General Staff recorded their opinion that the Americans were too soft-bodied to endure the physical hardships and moral stress of a long submarine campaign. As a result, the Japanese fleet completely neglected preparations for anti-submarine warfare - and this mistake turned out to be fatal. Constantly short of a merchant fleet, Japan found itself strangled by the American submarine fleet - just as Great Britain, overwhelmed by German submarines in the Atlantic, almost suffered the same fate. Towards the end of the war, one of the most famous American submariners, Medal of Honor recipient "Red" Ramage, said:

“...we found out that we took part in the first “wolf pack” in the Pacific Ocean. We adopted the successful experience of the German “wolf packs” operating in the Atlantic... More and more attacks were carried out at night from the surface.”

The vast expanses of the Pacific Ocean and the fanatical resilience of the Japanese became the reason for their ruthless attitude towards drowning people. Ramage adds:

Although the Japanese underestimated the threat from the American submarine fleet, they valued their own submarines very highly. Huge amounts of money and effort were spent on creating such underwater monsters as STO boats - a class with a displacement of 6,500 tons. Submarines equipped with aircraft became widespread. Many Japanese admirals were confident that it would be submarines, not aircraft carriers, that would have the decisive say in the attack on Pearl Harbor. A total of 28 Japanese submarines and five midget boats took part in the operation, without achieving any success.

Japanese submarines constantly fought against enemy warships. They always had to confront the most powerful ships of the American fleet. But the contribution of submarines to the war was determined by their use against the weak: they were supposed to torpedo tankers and transport ships.

From the book Japan in the War of 1941-1945. [with illustrations] author Hattori Takushiro From the book Questions and Answers. Part I: World War II. Participating countries. Armies, weapons. author Lisitsyn Fedor ViktorovichPearl Harbor. American, Japanese aviation > By the way, according to the veteran pilots who fought during Pearl Harbor, the Japanese during the battle did not see American mustangs flying close to the right or left side... I think this is also not a coincidence... At the time of the attack on

From the book 50 famous mysteries of the history of the 20th century author Rudycheva Irina AnatolyevnaThe mystery of the attack on Pearl Harbor The tragedy that occurred on December 7, 1941 at the Pearl Harbor military base, located on the Hawaiian Islands, marked Japan's entry into World War II. On that day, Japanese aircraft bombed the main forces of the American

From the book 500 famous historical events author Karnatsevich Vladislav LeonidovichJAPANESE ATTACK ON PEARL HARBOR Japanese Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, initiator of the attack on Pearl Harbor. The tragedy of September 11, 2001 is often compared with the events of December 1941. Pearl Harbor and the terrorist attack on the Trade Center towers shocked the entire American society. Before

From the book History of Humanity. West author Zgurskaya Maria PavlovnaPearl Harbor (1941) The Japanese attacked the US Navy base in Hawaii from the air, the American fleet suffered catastrophic losses. The tragedy of September 11, 2001 is often compared to the events of December 1941. Pearl Harbor and the terrorist attack on the Trade Center towers shocked everyone

From the book Aircraft Carrier AKAGI: from Pearl Harbor to Midway author Okolelov N NAKAGI in the attack on Pearl Harbor On November 22, a 23-ship task force intended to attack Pearl Harbor assembled at Hitokappu Bay in the Kuril Islands. The formation consisted of a strike group, a cover group and a supply group. Strike group under

From the book Richard Sorge - The Feat and Tragedy of a Scout author Ilyinsky Mikhail MikhailovichPearl Harbor The Third Hague Convention of 1907 established: “The Contracting Parties recognize that hostilities between them shall not commence without prior and express warning, either by a declaration of war or by

From the book History of the Far East. East and Southeast Asia by Crofts AlfredAttack on Pearl Harbor The morning attack, favored by clear weather and complete surprise, dealt a devastating blow to the US Pacific Fleet: one battleship was destroyed, four battleships rested in the shallow bottom of the harbor, three more were removed from

From the book Lend-Lease Mysteries author Stettinius EdwardChapter 14: Pearl Harbor and the United Nations At dawn on December 7, 1941, the heavy air transport departed Wake Island for Guam, en route from Manila to Hong Kong with a large number of spare parts on board; this cargo was urgently needed by General Chenol and his

From the book Odyssey of the USS Enterprise author Blon GeorgesI. Pearl Harbor The Pacific Ocean is so large that it could more than accommodate all the lands of our planet - continents, archipelagos, individual islands and islets. And it is no coincidence that back in time immemorial it was called the Great Ocean. South Sea or Southern Ocean. He called him quiet

by Baggott Jim From the book The Secret History of the Atomic Bomb by Baggott JimPearl Harbor Japan was a small island power with very limited natural resources, but with considerable ambitions. Surrounded from childhood by a culture in which the warrior was considered a sacred figure, Japanese writers and poets of the late 19th century developed the idea in detail

From the book Japan in the War of 1941-1945. author Hattori TakushiroCHAPTER VII ATTACK ON PEARL HARBOR The Japanese operational plan called for an air strike against the main forces of the American Pacific Fleet based in Hawaii, using six aircraft carriers of the 1st Fleet. To accomplish this task, maneuverable

From the book Secret Meanings of World War II author Kofanov Alexey NikolaevichPearl Harbor Simultaneously with the Battle of Moscow, an event occurred that was directly related to it. Even though it happened very far away... Having crushed Manchuria and Korea, the Japanese did not calm down - they began to seize colonies of countries defeated by the Reich: it would be a sin not to pick up what was ownerless. So they

Illustration copyright

AP Image caption The battleship "Arizona" took off with its entire crew75 years ago, Imperial Japan attacked the main US Pacific Fleet base at Pearl Harbor on the Hawaiian island of Oahu.

In 1941, like for the USSR, the war for the United States began with a surprise attack by the enemy, heavy losses and moral shock.

- The fleet is a weapon of the 21st century

Pearl Harbor marked the beginning of a new era in naval affairs. Aircraft carriers replaced large artillery ships as the main striking force.

The success of the Japanese was resounding, although not as devastating as it first seemed.

However, how did Japan even decide to attack the United States, which was superior in strength in all respects?

And why did Hitler declare war on America after Pearl Harbor, acquiring an extra enemy, although by that time it had already become clear that the blitzkrieg against the USSR had failed?

Chinese knot

At the beginning of 1932, the Japanese occupied Manchuria and created the puppet state of Manchukuo there, and in July 1937 they launched full-scale military operations against China and soon occupied Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Nanjing and other important cities.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, America has defended the “open door principle” in relation to China, categorically objecting to any attempts by other powers to divide it into spheres of influence, especially to seize it for their sole use.

The loss of China in 1949 was perceived in the United States as a foreign policy disaster - after all, it was largely because of it that they entered World War II.

In addition, after the defeat of France by the Nazis, Japan in September 1940 received Vichy’s consent to the “protective occupation” of French Indochina, and in March 1941 sent troops to neutral Thailand.

Effective sanctions

Demanding the withdrawal of Japanese troops from China and Southeast Asia, on September 26, 1940, the United States imposed an embargo on the supply of iron and scrap metal to Japan, and on July 26, 1941, on oil and petroleum products.

The latter measure was joined by Britain and the government of the Hitler-occupied Netherlands, which moved to London.

“Japan lost its vital sources of oil at one blow,” Winston Churchill wrote in his memoirs.

The empire's minimum oil needs were 28 thousand tons per day; the navy alone, while at sea, consumed 400 tons of liquid fuel per hour, and there was nowhere to get this fuel.

The sanctions presented Tokyo with a choice: either change course or try to seize, for starters, Dutch Indonesia, where there were oil deposits, which required first neutralizing the American fleet.

At that time, there was no thought of abandoning the imperial idea in Japan.

“The Mikado was told directly that if he went against military policy, he would be killed,” US Ambassador to Tokyo Joseph Grew stated in a diplomatic dispatch.

“The main factor that accelerated the attack on Pearl Harbor was oil. Or rather, the Japanese’s lack of it,” pointed out American historian David Roll.

"Northerners" and "Southerners"

In December 1939, the Japanese government, considering the war against China practically won, limited spending on it to 20 percent of scarce materials and 40 percent of the military budget.

There was a dispute between the “northern” and “southern” parties about the direction of further expansion: the Soviet Far East or the Pacific basin.

Unlike the Germans, who based their assessments of Soviet military power mainly on an analysis of the experience of the war with Finland, which was not entirely successful for Moscow, the Japanese did not consider Russia a weak adversary after Khalkhin Gol.

Even if successful, the capture of the sparsely populated cold territory, where oil was not extracted at that time, promised few benefits for Tokyo and did not fundamentally solve its problems. Moreover, in the event of the defeat of the USSR by the Germans, Siberia would fall into Japanese hands without a fight.

Illustration copyright AP Image caption According to analysts, Emperor Hirohito was a hostage of the "war party"The final choice was made at a meeting with the Emperor on July 2, 1941: “Although our attitude towards the Soviet-German war is determined by the spirit of the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo axis, we will not interfere in it […], we will use weapons if the course of the Soviet-German "The war will take a favorable turn for Japan."

It was then decided to prepare a strike in the south.

Stalin, not believing Richard Sorge’s forecasts about a German attack on the USSR, considered the resident’s analytical calculations regarding the Japanese attack against the United States logical and convincing and benefited a lot from it, even before Pearl Harbor he began transferring Siberian, or more precisely, Far Eastern divisions to Moscow.

Contrary to the well-known version that US intelligence cracked the Japanese "Purple" code and knew almost all the secrets of the future enemy, its analysts were not up to par.

On July 5, Army Headquarters sent a document to local commanders stating that war between Japan and the Soviet Union was highly likely.

Short fight

In July 1941, Japanese naval torpedo bombers began training in Kagoshima Bay, which was reminiscent of Pearl Harbor in configuration.

On September 5, Chief of the General Staff Hajime Sugiyama and Chief of Naval Staff Osami Nagano reported to the Emperor about their readiness. At the same time, Sugiyama assured that retaliatory airstrikes on Japanese territory are technically impossible for the Americans.

Illustration copyright Reuters Image caption The battleship West Virginia burned and sank, but after five months it was raised and repairedOn November 26, the squadron under the command of Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo left the Hitokappu base (now Kasatka Bay) on Iturup Island and headed for Pearl Harbor. During the 10 days of sailing, the ships were not discovered.

The main striking force consisted of six aircraft carriers: Akagi, Hiryu, Soryu, Shokaku, Juikaku and Kaga, which carried 441 aircraft, including 144 carrier-based torpedo bombers Nakajima B5N, which were considered that moment the best in the world in its class.

The guard consisted of two battleships, two heavy and one light cruiser, 11 destroyers and six submarines.

At 03:00 on December 7 - almost at the same hour when the Germans began artillery preparation on June 22 - 89 aircraft of the first wave (49 in the bomber version, the rest carried heavy torpedoes) took off from aircraft carriers and struck the American ships anchored in the bay .

Almost instantly, torpedo bombers from the Akagi hit the battleship Oklahoma. Then seven torpedoes hit the West Virginia. The next targets were the battleships Arizona, on which a monstrous explosion occurred, Tennessee, California, and Nevada.

54 Nakajima bombers of the second wave attacked coastal airfields.

Everything lasted 90 minutes. The carriers then boarded their aircraft, turned around and left.

A total of 353 aircraft, including escort fighters, took part in the two raids.

Illustration copyright AP Image caption Hickam Field Military Airfield: Dozens of planes were destroyed before they could take off.The Japanese sank four American battleships (two were subsequently raised and returned to service), two destroyers and one minelayer, damaged four more battleships, three cruisers and one destroyer, destroyed, mostly on the ground, 188 aircraft and damaged 159.

2,403 American troops were killed (almost half of them on board the Arizona that exploded) and 1,178 were wounded.

Japanese losses amounted to 64 men, 29 aircraft (15 bombers, five torpedo bombers and nine fighters) and five midget submarines.

By the way, the Japanese command had high, but completely unfulfilled, hopes for these boats delivered on board the ships. Lieutenant Sakamaki was captured after his midget submarine ran into a reef.

Pyrrhic victory

In terms of immediate effect, the success of the operation exceeded all expectations.

The American fleet took six months to recover from its losses. During this time, Japan captured Indonesia, the Philippines, Burma, Malaya, Hong Kong and Singapore with relative ease. Its fleet entered the Indian Ocean.

Berlin invited the ally to land troops in the south of the Arabian Peninsula, and after the capture of the Suez Canal by Rommel, lead its ships to the Mediterranean Sea.

- World War II: Erwin Rommel

Britain urgently began to strengthen India's defenses and took control of Madagascar, which was ruled by the Vichy French.

However, when the first shock passed, it became clear that US losses were not critical.

The base at Pearl Harbor remained operational. The piers, arsenal, fuel storage facilities, shipyard, power plant, and headquarters buildings were not damaged.

And most importantly, American aircraft carriers and the two newest and most powerful battleships, North Carolina and Washington, were in other places during the attack. Eight more similar ships were being completed.

Retribution was not long in coming. Already on April 18, 1942, bombers from the Hornet aircraft carrier refuted the assurances of General Sugiyama by striking Tokyo, Nagoya and Yokosuka (the “Doolittle Raid”).

On June 4-5, the United States won a key victory over the Japanese fleet at Midway Atoll. “Stalingrad at Sea” marked a turning point in the Pacific War, turning Japan once and for all into a defender.

Four of the six Japanese aircraft carriers that took part in the attack on Pearl Harbor were sunk at Midway. Of the 22 ships in the squadron, only one survived by the end of the war.

Conspiracy version

On December 8, Franklin Roosevelt spoke at a joint meeting of the US Senate and House of Representatives, calling the attack on Pearl Harbor “a day that will go down in history as a symbol of shame.” Lawmakers declared war on Japan.

Adherents of conspiracy theories believe that Roosevelt, having taken away valuable aircraft carriers from Hawaii, deliberately exposed obsolete ships to attack in order to disarm the isolationists. Nonconformist historians James Rusbridger and Eric Nave even titled their book Betrayal at Pearl Harbor.

As confirmation, they point out that Roosevelt rejected the admirals’ proposal to withdraw the fleet to San Diego for the winter after the end of summer-autumn exercises, saying that “a robber should always see a policeman in front of him.”

In January 1941, Secretary of the Navy Franklin Knox and Ambassador to Tokyo Joseph Grew suggested that if Japan decided to go to war, Pearl Harbor would be the first target.

The writer Samuel Morrison wondered why, in the four months before the attack, "almost nothing" was done to improve military readiness, although after the oil embargo it did not take a brilliant analyst to foresee such a development.

Pearl Harbor and Oahu were not prepared either mentally or physically for what happened on December 7 Samuel Morrison, American writer

In fact, Chief of the Naval Staff Harold Stark sent a warning to Pearl Harbor base commander Admiral Kimmel on November 27 about the “possibility of hostile action by Japan at any time” and repeated it the next day.

According to some reports, the Japanese planted disinformation about the start of the war on November 29, and when this date passed, the Americans calmed down.

The situation in the United States on the eve of Pearl Harbor was in many ways reminiscent of what was happening in the USSR before June 22: the same lack of reliable data, analytical fortune-telling, orders to be on full alert and at the same time not to panic, a paradoxical combination of anxiety and carelessness. And, as you know, everyone is strong with hindsight.

Franklin Roosevelt really believed that America should take part in the war so as not to leave Eurasia at the mercy of "devil-possessed" dictators, and the Japanese attack gave him a free hand.

But he had no reason to deliberately lead his fleet to destruction. It would be better in all respects if the attacking enemy received a worthy rebuff.

Fatal Delusion

At a government meeting in the summer of 1941, Colonel Hideo Iwakura from the Armaments Directorate of the War Ministry presented data on the available resources of the United States and Japan: aircraft 5:1, warships 2:1, labor 5:1, steel smelting 20:1, oil production 100: 1, coal 10:1.

Iwakura was sent to serve in Cambodia. However, the main author of the idea of attacking Pearl Harbor, Navy Commander-in-Chief Admiral Shuroku Yamamoto, who once graduated from Harvard and then worked as a naval attaché in Washington, had no illusions about Japan’s chances in a stubborn war and relied on blitzkrieg.

The Germans could still, at least theoretically, hope to defeat the Red Army in three months and reach the Arkhangelsk-Volga line. But what kind of blitzkrieg were we talking about in relation to the United States located overseas?

Illustration copyright AP Image caption Franklin Roosevelt declares war on JapanRussian historian Igor Bunich saw the answer in “a misunderstanding of the origins of American power and optimism.”

No one in Japan was going to land near San Francisco and fight against Washington. The idea was that it would be enough to inflict a couple of serious blows on the Americans for the number of victims to go into the thousands - and then the mothers and brides of bank clerks, baseball players and jazz musicians drafted into the army would stage a demonstration in front of the White House and force Roosevelt to make peace on any terms.

“From Tokyo, as well as from Berlin and Moscow, the States seemed to be a disheveled, completely undisciplined country with a dissolved, decomposed, completely devoid of ideology population, incapable of the sacrifices that a great war requires,” the researcher wrote.

“Who will fight? I couldn’t believe that these sleek young people in bow ties, playing tennis and swimming in pools, could sit in a trench for at least half an hour and not start a rally about the violation of their civil rights. The opponents miscalculated by not guessing deceptive appearance, iron muscles and deadly fangs."

The oddities of Hitler's behavior

On December 11, 1941, Germany declared war on America. Ribbentrop called US Chargé d'Affaires Leyland Morris and, without inviting him to sit down, shouted in a pathetically hysterical manner: “Your president wanted war. Now he got it.”

Roosevelt first expressed his attitude towards European dictators back in early 1936. In a speech on January 3, the immediate occasion of which was Italian aggression against Ethiopia, he said: “The time has come when the American people must pay attention to the growing evil, to the obvious aggression, to the growth of armaments, which are creating the preconditions for the tragedy of a general war.”

On September 28, 1940, he passed through Congress the law on universal conscription, on March 8, 1941, the Lend-Lease law, while publicly declaring that “all countries that are fighting Nazism or will join the fight against it will receive everything they need from the United States so that this struggle ends victoriously."

- Franklin Roosevelt's garden hose

On December 8, 1941, the President said: "We intend to end the threat from Japan. But we will achieve little if the rest of the world remains under the heel of Hitler and Mussolini."

The very low level of coordination of strategic plans and specific actions between Germany and Japan is still a mystery Konstantin Remchukov, historian and publicist

So Roosevelt did not hide his views, and American neutrality was relative.

Nevertheless, the Germans had a chance to avoid a direct confrontation or at least delay it. No one, as they say, pulled their tongues with the declaration of war.

According to historians, Hitler hoped that Japan would respond by at least symbolically declaring war on the Soviet Union.

On July 10, Ribbentrop, in a message to his Japanese colleague Yosuke Matsuoka, expressed the hope of “shaking Japan’s hand on the Trans-Siberian Railway before the start of winter,” and on November 21, he secretly assured his partners of support in the event of war with America.

The calculation did not come true, and a few months later the defeat of the Japanese fleet at Midway Atoll finally deprived Tokyo and Berlin of the opportunity to pursue any coordinated strategy.

Grigory Gelfenshtein, senior sergeant, former senior operator of the REDUT-3 radar

December 7, 1941. Pearl Harbor is a US naval base in the central Pacific Ocean on the island. Oahu, where the main forces of the American Pacific Fleet were located. With the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan entered World War II as an ally of Hitler's Germany.

The idea of this operation was to covertly approach and launch a sudden massive air strike on American ships, coastal structures and aircraft at the airfield at Pearl Harbor.

By December 7, there were 93 ships and support vessels in Pearl Harbor. Among them are 8 battleships, 8 cruisers, 29 destroyers, 5 submarines, 9 minelayers and 10 minesweepers of the US Pacific Fleet. The air force consisted of 394 aircraft, and the air defense of Pearl Harbor was provided by 294 anti-aircraft guns.

Ships in the harbor and planes at the airfield were crowded together, making them a convenient target for attack. The base's air defense was not ready to repel attacks. Most of the anti-aircraft guns were not manned, and their ammunition was kept under lock and key. In short, the Japanese were not expected here.

“At the end of November 1941, the SCR-270 early warning radar station was delivered to the US Pacific Fleet naval base on the Hawaiian Islands in Pearl Harbor. It was installed on the northern tip of the island of Oahu, on Mount Opana, and put into operation.

On December 7, 1941, the station duty shift at 7:02 a.m. saw a large target at a distance of 136 miles (220 km). After a long 7 minutes, when her coordinates were determined, the officers on duty tried to report this to the information center located at Fort Schefter. No one answered the phone for a long time. Finally, the pursuit aviation liaison officer responded, who was supposed to inform the command about the approach of unknown aircraft.

After listening to the radar operator’s message, he decided that these were his own planes and instructed the radar station duty shift to “not pay attention to these planes.”

The duty shift continued to observe the target. At a distance of 20 miles, the target entered the "dead zone" and disappeared from the indicator screen. It turned out that these were Japanese planes flying to strike the ships stationed in Pearl Harbor." (From the book by E.Yu. and E.A. Sentyanin "Redoubts" in the defense of Leningrad", Lenizdat, 1990 p. .62)

The Japanese naval command, knowing the deployment of ships in Pearl Harbor, developed a plan for a surprise attack and destruction of the American fleet.

On November 26, 1941, a Japanese carrier force consisting of two battleships, six aircraft carriers with 353 aircraft, nine destroyers and three submarines, under the command of Admiral Amamoto, in the strictest secrecy, left Hata-kapu Bay on the Kuril Islands and headed south.

On the night of December 7, the Japanese squadron arrived in an area 350-500 kilometers north of the island of Oahu. By this time, 27 Japanese submarines had already taken positions off the Hawaiian Islands.

In the early morning of December 7, torpedo-carrying and bomber aircraft launched from Japanese aircraft carriers launched two powerful successive attacks on American ships, airfields, and coastal batteries. The entire operation lasted less than two hours.

On December 7 at 6.00, 183 aircraft of the first wave took off from aircraft carriers and headed for the target. There were 49 attack aircraft-bombers of the 97 type, each of which carried an 800-kilogram armor-piercing bomb, 40 attack torpedo bombers with a torpedo suspended under the fuselage, 51 dive bombers of the 99 type, each carrying a 250-kilogram bomb. The covering force consisted of three groups of fighters, numbering a total of 43 aircraft.

The skies over Pearl Harbor were clear. At 7:55 am, Japanese planes attacked all large ships and aircraft at the airfield. There was not a single American fighter in the air, and not a single gun flash on the ground. As a result of a sudden Japanese attack that lasted about an hour, 3 battleships were sunk and a large number of aircraft were destroyed. Having finished bombing, the bombers headed for their aircraft carriers. The Japanese lost 9 aircraft.

The second wave of aircraft (170 aircraft) took off from the aircraft carriers at 7:15 am. The second wave included 54 Type 97 attack bombers, 80 Type 99 dive bombers and 36 fighters that covered the bombers.